Abstract

It is thought that KRAS oncoproteins are constitutively active because their guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) activity is disabled. Consequently, drugs targeting the inactive or guanosine 5′-diphosphate–bound conformation are not expected to be effective. We describe a mechanism that enables such drugs to inhibit KRASG12C signaling and cancer cell growth. Inhibition requires intact GTPase activity and occurs because drug-bound KRASG12C is insusceptible to nucleotide exchange factors and thus trapped in its inactive state. Indeed, mutants completely lacking GTPase activity and those promoting exchange reduced the potency of the drug. Suppressing nucleotide exchange activity downstream of various tyrosine kinases enhanced KRASG12C inhibition, whereas its potentiation had the opposite effect. These findings reveal that KRASG12C undergoes nucleotide cycling in cancer cells and provide a basis for developing effective therapies to treat KRASG12C-driven cancers.

Wild-type RAS guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) cycle between an active, guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP)–bound, and an inactive, guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP)–bound, state (1, 2). This is mediated by nucleotide exchange factors, which catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP, and GTPase-activating proteins, which potentiate a weak intrinsic GTPase activity (3). Cancer-causing mutations impair the GTPase activity of RAS, causing it to accumulate in the activated state (4–6). Despite the prevalence of these mutations, no therapies that directly target this oncoprotein are currently available in the clinic (7–9). A recently identified binding pocket in KRASG12C (10) now enables the discovery of compounds that potently inhibit KRAS-GTP or effector signaling by this mutant.

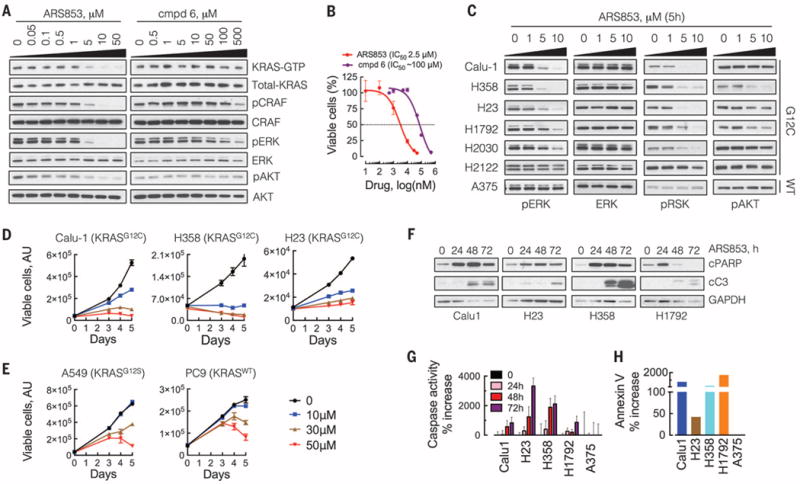

Here we characterize a novel compound, ARS853, designed to bind KRASG12C with high affinity (11). The structures of ARS853 and previously reported (10) compounds (cmpds) 6 and 12 are shown in fig. S1A. Treatment of KRASG12C-mutant lung cancer cells with ARS853 reduced the level of GTP-bound KRAS by more than 95% (Fig. 1A, 10 μM). This caused decreased phosphorylation of CRAF, ERK (extracellular signal–regulated kinase), and AKT. In contrast, even at the highest concentration tested, cmpd 6 or 12 had only a minimal effect on pCRAF and pERK, without affecting KRAS-GTP levels (Fig. 1A and fig. S1B). ARS853 inhibited proliferation with an inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50) of 2.5 μM, which was similar to its IC50 for target inhibition (Fig. 1, A and B). ARS853 (10 μM) inhibited effector signaling (Fig. 1C and fig. S1C) and cell proliferation (Fig. 1D and fig. S2) to varying degrees in six KRASG12C mutant lung cancer cell lines, but not in non-KRASG12C models (Fig. 1E and fig. S1, C and D). Similarly, it completely suppressed the effects of exogenous KRASG12C expression on KRAS-GTP levels, KRAS-BRAF interaction, and ERK signaling (fig. S1E). Inhibitor treatment also induced apoptosis in four KRASG12C mutant cell lines (Fig. 1, F to H). Thus, ARS853 selectively reduces KRAS-GTP levels and RAS-effector signaling in KRASG12C-mutant cells, while inhibiting their proliferation and inducing cell death.

Fig. 1. Selective inhibition of KRASG12C signaling and cancer cell growth by ARS853.

(A) KRASG12C mutant cells (H358) were treated with a novel (ARS853) or a previously described (cmpd 6) compound for 5 hours. The effect on the level of active, or GTP-bound, KRAS was determined by a RAS-binding domain pull-down (RBD:PD) assay and immunoblotting with a KRAS-specific antibody. The effect on ERK and AKT signaling was determined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. A representative of at least two independent experiments for each compound is shown. (B) H358 cells were treated for 72 hours with increasing concentrations of the indicated inhibitors, followed by determination of viable cells by the ATP glow assay (n = 3 replicates). (C) The effect of ARS853 treatment on the inhibition of signaling intermediates in a panel of KRASG12C-mutant lung cancer cell lines. KRASWTA375 cells were used as a control. A representative of at least two independent experiments for each cell line is shown. (D and E) The cell lines were treated over time to determine the effect of ARS853 on the proliferation of G12C (D) or non-G12C (E) KRAS models (n = 3 replicates). (F) The effect of ARS853 treatment on the cleavage of apoptotic intermediates was determined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. A representative of two independent experiments is shown. (G) Cell extracts from the indicated cell lines treated with ARS853 were subjected to a caspase activation assay with the Z-DEVD-AMC reporter substrate. The increase in fluorescence relative to untreated (0) is shown (n = 3 replicates). (H) Following treatment with ARS853 for 24 hours, the cells were stained with annexin V and evaluated by flow cytometry to determine the increase in annexin V–positive cells relative to untreated cells. Data in (B), (D), (E), and (G) are mean and SEM.

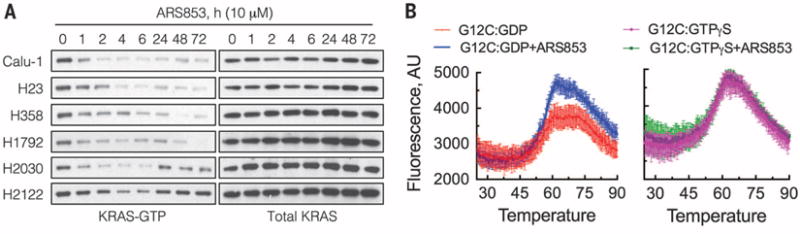

In contrast to the rapid inhibition of signaling by kinase inhibitors, inhibition of KRASG12C by ARS853 occurred slowly (Fig. 2A and fig. S3). In some cell lines, maximal inhibition of KRAS-GTP occurred in 6 hours; in others, in 48 to 72 hours. To understand this phenomenon, we examined the mechanism of KRASG12C inhibition in more detail. To determine whether ARS853 binds to the active or the inactive conformation of KRASG12C, we used differential scanning fluorimetry, which assays ligand-induced changes in protein thermal stability (12). Recombinant KRASG12C was loaded with either GTPγS or GDP (fig. S4A) and then incubated with ARS853. Samples were incubated at increasing temperatures in the presence of a fluorescent dye that binds to hydrophobic surfaces exposed during thermal denaturation. ARS853 increased the amplitude of the thermal denaturation curve of KRASG12C loaded with GDP but not with GTPγS (Fig. 2B and fig. S4B). ARS853 did not alter the denaturation curve of GDP-loaded KRASWT (fig. S4C). These data suggest that ARS853 preferentially interacts with inactive, or GDP-bound, KRASG12C.

Fig. 2. Inhibition of active KRAS levels despite an interaction with GDP-bound KRASG12C.

(A) KRASG12C-mutant lung cancer cell lines were treated with ARS853 (10 μM) over time, and cellular extracts were analyzed to determine the effect on KRAS-GTP as in Fig. 1A. (B) Recombinant KRASG12C was loaded with GDP or nonhydrolyzable GTPγS and then reacted with ARS853 at a 1:1 molar ratio for 1 hour, at room temperature. The samples were analyzed by differential scanning fluorimentry to determine the shift in thermal denaturation curve induced by ARS853 binding (n = 4 replicates for GDP and n = 3 replicates for GTPγS). Mean and SEM are shown.

KRAS mutants are thought to exist in a “constitutively” active (GTP-bound) state in cancer cells (13). Thus, inhibition of KRAS-GTP levels by a drug that preferentially interacts with GDP-bound mutant KRAS is puzzling. Codon 12 mutations disable the activation of RAS GTPase by GTPase-activating proteins (14–16). It is possible, however, that the basal GTPase activity of KRASG12C is sufficient to enable nucleotide cycling in cancer cells. Consequently, we hypothesized that binding of the inhibitor to KRASG12C traps it in an inactive (GDP-bound) conformation by reducing its susceptibility to exchange, which then results in the observed time-dependent reduction in cellular KRAS-GTP levels. For this to be the case, (i) inhibition by the drug should require KRASG12C GTPase activity. (ii) If KRASG12C GTPase activity is constant, the rate of RAS inhibition by the drug should depend on exchange factor activity. (iii) Regulating exchange factor activity should affect drug potency and the kinetics of inhibition.

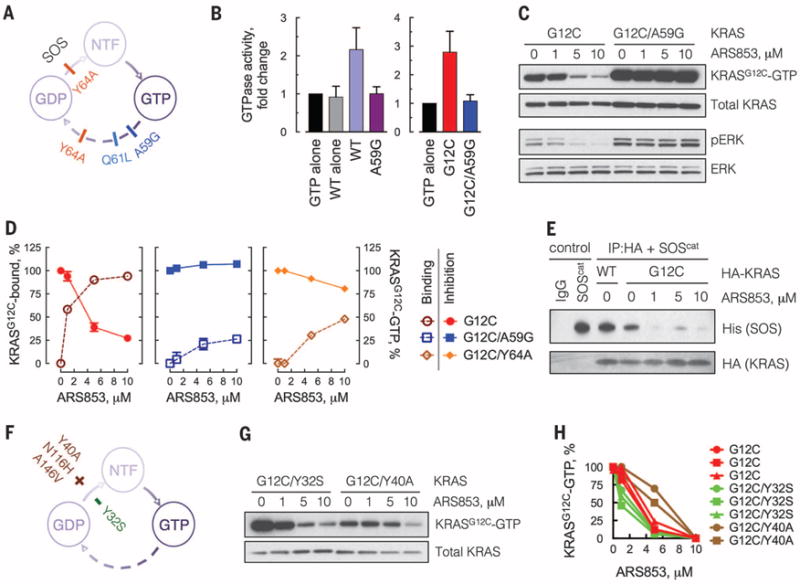

We tested this hypothesis by using mutations that occur in cancer patients and affect the guanine nucleotide cycle of RAS (Fig. 3A and fig. S5A). A59G is a “transition state” mutant that abrogates GTPase activity (17, 18). When assayed for their GTPase activity (Fig. 3B), KRASWT and KRASG12C generated approximately three times as much hydrolysis product as the control reactions, whereas KRASA59G or KRASG12C/A59G had little activity. Thus, KRASG12C has basal GTPase activity that is suppressed by the A59G mutation (see also Fig. 3C, lane 5 versus lane 1). ARS853 reduced KRAS-GTP levels and ERK phosphorylation in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) or H358 cells engineered to express KRASG12C but not in those expressing KRASG12C/A59G (Fig. 3C and fig. S5B). The crystal structure of HRASA59G shows that Q61, a critical residue for GTP hydrolysis, is displaced in this mutant (fig. S5C). Q61L impairs in vitro GTP hydrolysis by HRAS (19), and, when expressed in HEK293 cells, KRASG12C/Q61L was less sensitive to ARS853 than KRASG12C (fig. S5D). Y64A both reduces RAS GTPase activity and impairs the interaction of HRAS with the active site of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) SOS (18, 20, 21) (fig. S6, A to C). As expected, ARS853 caused only minimal inhibition of GTP-bound KRASG12C/Y64A or signaling driven by this mutant (fig. S6D). Thus, KRASG12C GTPase activity is required for its inhibition by ARS853.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of KRASG12C requires GTPase activity and is attenuated by nucleotide exchange.

(A) Schematic of the mutations used to block the GTPase activity of KRAS. NTF, nucleotide free. (B) KRAS mutants, expressed and affinity purified from HEK293 cells, were subjected to a GTPase reaction. The orthophosphate product was measured by the Cytophos reagent and expressed as fold change over GTP alone (n = 3, mean and SEM). (C) HEK293 cells expressing HA-tagged KRAS constructs were treated with ARS853 for 5 hours. Cell extracts were evaluated by RBD:PD and immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody, to determine the effect on GTP-bound mutant KRASG12C. A representative of three independent experiments is shown. (D) Extracts from cells expressing the KRAS constructs treated as shown were evaluated by mass spectrometry to determine the percentage of KRASG12C bound to the drug. KRASG12C-GTP levels in the same extracts were determined as in (C) and quantified by densitometry (n = 3, mean and SEM). (E) HEK293 cells expressing the constructs shown were treated with ARS853 for 5 hours. HA-tagged KRAS was immunoprecipitated (IP) and subjected to a binding assay with the catalytic domain of SOS (SOScat). (F) Schematic of the mutations used to biochemically increase (+) or decrease (−) the nucleotide exchange function of KRASG12C. (G) HEK293 cells expressing the indicated constructs were analyzed as in (C). (H) The level of active KRAS-GTP was quantified by densitometry. Each replicate is shown. A similar result was obtained in H358 cells (fig. S6F). The baseline level of KRASG12C/Y40A detected by the RBD:PD is low because the Y40 mutation impairs the interaction of RAS with RAF (33). See also the effects of N116H and A146V mutations, which increase nucleotide exchange without affecting RAS-RAF interaction (fig. S6G).

The percentage of KRASG12C bound to ARS853 in cells was evaluated by mass spectrometry (Fig. 3D, dotted line). GTPase-impairing mutations A59G or Y64A diminished the cellular interaction of ARS853 with KRASG12C by ~75 and ~50%, respectively. This effect was inversely proportional to their effect on KRASG12C-GTP inhibition (Fig. 3D, solid line), supporting the conclusions that ARS853 interacts preferentially with GDP-bound KRASG12C in cells and that GTPase activity is required for the drug to bind and inhibit KRASG12C.

ARS853 reduced the interaction of KRASG12C with the catalytic subunit of SOS (Fig. 3E) and attenuated SOS-mediated nucleotide exchange by KRASG12C (fig. S6E). These findings suggest that ARS853 traps KRASG12C in a GDP-bound conformation by lowering its affinity for nucleotide exchange factors. It is therefore possible that nucleotide exchange activity modulates the effect of ARS853. We tested whether RAS mutations that affect nucleotide exchange alter the sensitivity of KRASG12C to ARS853 (Fig. 3F). Y40A, N116H, and A146V increase, whereas Y32S decreases, nucleotide exchange (22–24). Mutations that increase exchange attenuated the effect of ARS853 on KRASG12C-GTP, whereas Y32S caused a small augmentation of its effect (Fig. 3, G and H, and fig. S6, F and G). These data imply that potentiation of nucleotide exchange reduces sensitivity to ARS853, by lowering the levels of GDP-bound KRASG12C available for drug binding.

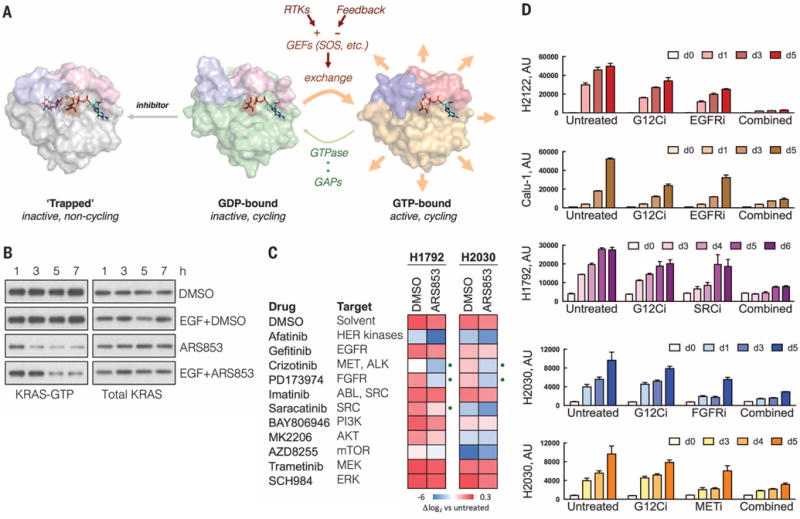

If the inhibitor works by the trapping mechanism suggested by these data (Fig. 4A), then cellular parameters regulating nucleotide exchange ought to modulate the inhibition of KRASG12C. Exposure to epidermal growth factor (EGF), an activator of SOS (25), delayed the inhibition of KRASG12C by ARS853 by several hours compared to inhibition in serum-free medium (Fig. 4B and fig. S7A). Treatment with an EGF receptor (EGFR) inhibitor (fig. S7, B and C) or SOS-specific small interfering RNAs (fig. S7D) had the opposite effect. We determined if EGFR signaling affects the inhibition of the mutant KRASG12C allele, by expressing hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged KRASG12C in EGFR-mutant PC9 cells, in which nucleotide exchange depends on EGFR (26, 27). The specific effect on the mutant allele was determined by pulling down active KRAS and then immunoblotting for HA-tagged KRASG12C. ARS853 inhibited GTP-bound KRASG12C more potently in the presence of gefitinib, as compared to its absence (fig. S7E). Furthermore, EGFR inhibition enhanced the suppression of KRAS-GTP levels by ARS853 in both KRASG12C homozygous and heterozygous cells (fig. S7F). Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling and nucleotide exchange are also subject to feedback inhibition by ERK or AKT (28). Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) or AKT inhibitors relieve this feedback and activated RTK signaling (29, 30). Inhibiting these pathways also attenuated the inhibitory effect of ARS853 (fig. S7, G and H). Taken together, these findings show that RTK-mediated nucleotide exchange regulates the kinetics and potency of KRASG12C inhibition in cancer cells.

Fig. 4. Tyrosine kinase activation of nucleotide exchange modulates KRASG12C inhibition in cancer cells.

(A) A schematic of the trapping mechanism by which ARS853 targets KRASG12C-dependent signaling and the role of RTK- or feedback-regulated nucleotide exchange in this process. Structures were adapted from Protein Data Bank accessions 4luc (inhibitor-bound KRASG12C-GDP), 4ldj (KRASG12C-GDP), and 4l9w (HRASG12C-GTP). (B) H358 cells were serum starved overnight followed by treatment with ARS853 (10 μM), with or without EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times, to determine the effect on KRAS-GTP. A representative of two independent experiments is shown. (C) The indicated cell lines, selected because of their relative insensitivity to KRASG12C inhibition, were treated with inhibitors of RTK signaling, alone or in combination with ARS853 for 5 days, in order to determine the most effective combinations. The effect of treatment is shown relative to the proliferation of untreated cells. The dots indicate combination treatments resulting in significantly more pronounced inhibition, compared to either drug alone (n = 3 replicates, mean). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. (D) The effect of inhibitors targeting tyrosine kinases on the antiproliferative effect of KRASG12C inhibition in KRASG12C mutant cell lines (n = 3 replicates, mean and SEM). The concentrations of the inhibitors used in (C) and (D) are noted in Materials and Methods.

The above results also suggest that pharmacologic inhibition of the exchange reaction, as achieved, for example, with inhibitors of RTK signaling, ought to potentiate the antiproliferative effect of KRASG12C inhibitors. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the effects of 11 inhibitors targeting RTKs, or their downstream signaling pathways, in KRASG12C-mutant cell lines. In agreement with our model, inhibiting the tyrosine kinase activities of MET, SRC, or FGFR (fibroblast growth factor receptor) enhanced growth inhibition by ARS853 in H1972 and H2030 cells, whereas MEK, ERK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), or AKT inhibitor treatment did not have a significant effect (Fig. 4, C and D). In H2122 and Calu-1 cells, the effect of ARS853 was potentiated by concurrent inhibition of EGFR (Fig. 4D). Inhibition of EGFR also enhanced the induction of caspase activity by ARS853 (fig. S7I). These findings support another report showing that EGFR is required for KRAS-driven cancer formation (31) and suggest that the RTKs responsible for modulating the timing of KRASG12C inhibition in lung cancer vary from tumor to tumor. They also provide a rationale for selecting optimal combination treatments to achieve maximal KRASG12C inhibition in patients.

We thus report an inhibitor that suppresses KRASG12C signaling and tumor cell growth by binding to the GDP-bound form of the protein. This reduces the levels of KRASG12C-GTP, because the protein retains GTPase activity and undergoes nucleotide cycling in cells. Some RAS mutants have low levels of basal GTPase activity in vitro; yet, perhaps owing to an inability to directly test such activity in vivo, these oncoproteins are assumed to be constitutively GTP-bound in cancer cells. The data presented here, however, indicate that inhibition by ARS853 requires GTPase activity and that nucleotide exchange activity is inversely related to the kinetics and/or magnitude of inhibition. The model suggests that the RAS inhibitor and exchange factors compete for binding to KRASG12C-GDP. Drug-bound KRASG12C-GDP is not susceptible to exchange and exits the cycle, thus lowering the levels of KRASG12C-GTP.

This model also predicts that genetic alterations that completely disable KRASG12C GTPase activity, or those that activate nucleotide exchange function, will confer resistance to this class of drugs. Careful selection of combination therapies may in turn prevent or delay the emergence of resistance by enabling a more potent inhibition of KRASG12C. The mechanism of action elucidated here establishes a basis for such combination therapies. Inhibitors of receptors dominantly responsible for activation of RAS nucleotide exchange are predicted to enhance activity, whereas inhibitors of downstream pathways that reactivate these receptors are likely to blunt inhibition of mutant KRAS.

KRASG12C mutations occur in 16% of lung adenocarcinomas (32), making them one of the most frequent activating genetic alterations in lung cancer, a disease responsible for approximately 1.6 million annual deaths worldwide. No effective inhibitor of mutant KRAS has yet been developed for use in the clinic. Our results suggest that KRASG12C allele–specific inhibitors, such as the one described here, merit investigation as potential therapeutics for KRASG12C-lung cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Sawyers and M. Mroczkowski for reviewing the manuscript. This work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health (P01CA129243-06 to N.R. and P.L.; K08CA191082-01A1 to P.L.), the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Experimental Therapeutics “Big Bets” program (SKI12103 to N.R. and P.L.), the LUNGevity Foundation Career Development Award (P.L.) and the V Foundation Translational Grant (P.L.). N.R. is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Wellspring Biosciences and has received grant support from this organization. L-S.L. and R.H. are employees of Wellspring Biosciences. ARS853 was obtained from Wellspring Biosciences under a material transfer agreement. L-S.L. is an inventor on a patent held by Araxes Pharma LLC (an affiliate of Wellspring Biosciences) that covers ARS853.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/351/6273/604/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

References (34–36)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RK, McCormick F. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. Cell. 2007;129:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parada LF, Tabin CJ, Shih C, Weinberg RA. Nature. 1982;297:474–478. doi: 10.1038/297474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos E, Tronick SR, Aaronson SA, Pulciani S, Barbacid M. Nature. 1982;298:343–347. doi: 10.1038/298343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taparowsky E, et al. Nature. 1982;300:762–765. doi: 10.1038/300762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bollag G, Zhang C. Nature. 2013;503:475–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, Luo J, Der CJ. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:828–851. doi: 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiegel J, Cromm PM, Zimmermann G, Grossmann TN, Waldmann H. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:613–622. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. Nature. 2013;503:548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patricelli MP, et al. Cancer Discov. 2016:CD-15-1105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gysin S, Salt M, Young A, McCormick F. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:359–372. doi: 10.1177/1947601911412376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bollag G, McCormick F. Nature. 1991;351:576–579. doi: 10.1038/351576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheffzek K, et al. Science. 1997;277:333–338. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. Science. 2001;294:1299–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1062023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall BE, Bar-Sagi D, Nassar N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12138–12142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192453199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margarit SM, et al. Cell. 2003;112:685–695. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MJ, Neel BG, Ikura M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4574–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218173110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boriack-Sjodin PA, Margarit SM, Bar-Sagi D, Kuriyan J. Nature. 1998;394:337–343. doi: 10.1038/28548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sondermann H, et al. Cell. 2004;119:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feig LA, Cooper GM. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2472–2478. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.6.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall BE, Yang SS, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Kuriyan J, Bar-Sagi D. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27629–27637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel G, MacDonald MJ, Khosravi-Far R, Hisaka MM, Der CJ. Oncogene. 1992;7:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell. 2010;141:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pao W, Chmielecki J. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:760–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chin TM, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6867–6876. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lito P, Rosen N, Solit DB. Nat Med. 2013;19:1401–1409. doi: 10.1038/nm.3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandarlapaty S, et al. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lito P, et al. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:668–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navas C, et al. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collisson EA, et al. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez-Viciana P, et al. Cell. 1997;89:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.