Abstract

Impressions of others, including societal groups, systematically array along two dimensions, warmth (trustworthiness/friendliness) and competence. Social structures of competition and status respectively predict these usually orthogonal dimensions. Prejudiced emotions (pride, pity, contempt, and envy) target each quadrant, and distinct discriminatory behavioral tendencies result. The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) patterns generalize across time (2oth century), culture (every populated continent), level of analysis (targets from individuals to subtypes to groups to nations), and measures (from neural to self-report to societal indicators). Future directions include individual differences in endorsement of these cultural stereotypes and how perceivers view combinations across the SCM space.

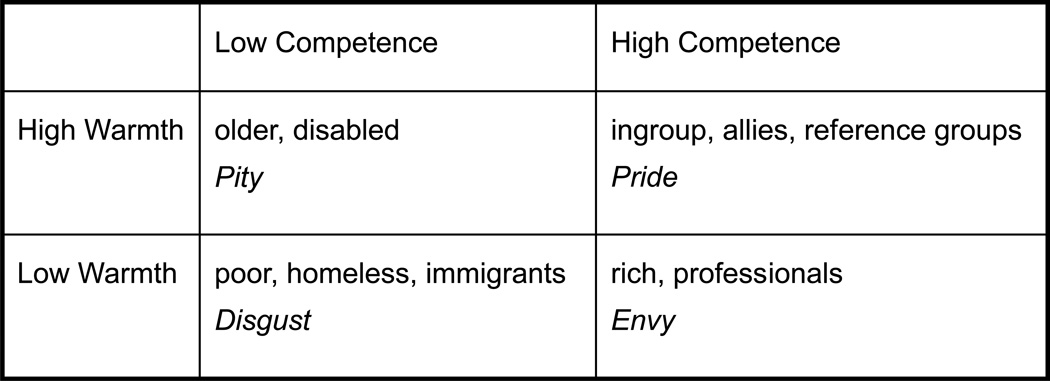

The earliest social psychology of stereotypes documented their content (1, and then replicated and extended by 2–4). With few exceptions, the rest of the 20th century focused on processes of stereotyping (e.g., social categorization, 5–6). At the outset of the 21st century, the Stereotype Content Model identified two systematic dimensions of stereotyping (7; see Figure 1): warmth and competence.

Figure 1.

Stereotype Content Model, typical outgroup locations.

Precedents for these two dimensions include decades of impression formation research (see 7–8, for reviews), especially Asch’s (9) foundational research using a competent person who was either warm or cold and Abele and Wojciszke’s (e.g., 10–11) more modern identification of communality/morality (warmth) and agency/competence as two orthogonal dimensions, accounting for as much as 80% of the variance in impressions.

The distinctive SCM contribution, identifying mixed stereotypes high on one dimension but low on the other, also has precedents and parallels: ambivalent sexism (dumb-but-nice vs. competent but cold; 12), doddering-but-dear old-age stereotypes (13–14), smart-but-not-social anti-Asian stereotypes (15).

Overview

The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) is a simple framework (BIAS Map: 16; SCM: 7, 8, 17):

Social Structure→Stereotypes→Emotional Prejudices→Discriminatory Tendencies Stereotypes

This overview starts with the warmth × competence stereotype space. Early work (7, 17) hypothesized and found that (a) Perceived competence and warmth differentiate group stereotypes; and (b) Many stereotypes include mixed ascriptions of competence and warmth. Generally replications support these findings in more recent American convenience samples (2, 18) and in representative samples (16).

Warmth reflects the other’s intent, so it is primary and arguably judged faster (19). Competence reflects the others ability to enact that intent, so it is secondary and judged more slowly. The most valid traits reflecting warmth include seeming trustworthy and friendly, plus sociable and well intentioned. Competence includes seeming capable and skilled. Moreover, validity also increases because the four warmth-by-competence clusters also differ on the other hypothesized variables: perceived social structure, emotional prejudices, and discriminatory behavioral tendencies.

Social Structure

Given evidence of the warmth-by-competence space, SCM research has tested for their respective antecedents: (a) Status predicts perceived competence, while (b) interdependence (competition/cooperation) predicts stereotypic warmth. The status-competence correlations are surprisingly robust, usually over r = .80, and generalizing across cultures (average r = .90, range = .74 – .99, all p’s < .001; 20). Status is measured as economic success and prestigious job, so evidently the belief in meritocracy is widespread. The status-competence correlation persists across stable and unstable status systems (21).

The cooperation-warmth (and competition-cold) correlations have been more uneven until lately. In early data, perceived competition did correlate negatively with perceived warmth, r = −11. – .68), consistent but small effects (averaging −.32), sometimes not significant (20). Closer examination has refined these predictions (18). Warmth most appropriately includes both sociability and trustworthiness/morality, as in the earliest SCM studies, and consistently with the close relationship between trustworthiness and friendliness. Competition predicts most robustly when it includes not only economic resources but also values.

Emotional Prejudices

Whereas the preceding hypotheses—structure (interdependence, status) → stereotype (warmth, competence)—predict main effects, the stereotype → emotional prejudice hypotheses predict interactions. Each quadrant’s warmth-by-competence combination predicts distinctive emotions:

High warmth, high competence, the combination that includes the society’s prototypic ingroups, such as the middle class, elicits pride and admiration.

Low warmth, low competence, the quadrant that contains societal outcasts, such as homeless people, elicits contempt and disgust.

Low warmth, but high competence, the mixed combination that includes successful outsiders, such as rich people, elicits envy and jealousy.

High warmth, but low competence, the mixed quadrant includes benign subordinates, such as old or disabled people, elicits pity and sympathy.

The predictions derive from social theories of emotion, and a variety of SCM studies confirm them (7, 16). Moreover, individual groups located in each quadrant provide case studies of specific emotional dynamics of (e.g.) disgust or envy (see below).

Discriminatory Behavioral Tendencies (the BIAS Map)

The Behavior from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes (BIAS) Map extends the SCM to distinctive discriminatory tendencies (16). Predictions from stereotype dimensions are main effects. Because the warmth dimension is primary, it predicts active reactions, both positive (high warmth predicts helping and protecting) and negative (low warmth predicts attacking and fighting). Because the competence dimension is secondary, it predicts more passive reactions, both positive (associating) and negative (neglecting).

The behavioral combinations, as reported by participants, are informative about varieties of discrimination. The high-high pride groups of course elicit both helping and associating. The low-low groups elicit both active harm and passive neglect, behavior characteristically directed toward homeless people.

The mixture of passive association and active harm describes reactions toward outsider entrepreneurs, whose businesses the majority may patronize in peace and stability, but the envied are also the targets of mass attacks under social breakdown. The mixture of active help but passive neglect describes institutionalizing pitied outgroups.

Between intergroup stereotypes and affect, the emotional prejudices more strongly and immediately predict behavior (16; see also 22 for a meta-analysis regarding racial biases).

Validity

Convergent and Divergent Validity: Overlap and Distinctiveness

Several parallel models are nonetheless distinct from the SCM. One comprehensive model of generic attitudinal dimensions, the Semantic Differential, identifies evaluation, potency, and activity as key (23). In social cognition, the last two dimensions collapse together, so one might assume that evaluation-by-potency/activity would be redundant with warmth-by-competence. However, these dimension operate at 45-degree angle to the SCM space (24). Evaluation runs from the low-low quadrant to the high-high quadrant (being high on either warmth or competence is good). Potency/activity runs from the unthreatening warm–but-incompetent quadrant to the threatening cold-but-competent quadrant.

In individual person perception, other relevant parallels include social good-bad and task good-bad (25), morality and competence (26), trustworthiness and dominance (19). In intergroup and inter-nation relations, similar dimensions emerge (respectively, 27, 28; see 29, 30, for discussions of the distinctions).

External Validity: Generalizing over Time

The SCM space is not simply a product of modern, immigrant-receiving liberal democracies leaning toward the politically correct notion that most outgroups have at least one positive side. The SCM dimensions emerge in the oldest studies of stereotypes (1), replicated across the 20th century and re-analyzed in the 21st (2). Americans and British stereotypes persist as high on both dimensions; Turks persist as low on both. Asians remain competent but cold. And “Negroes”/African Americans appear warm but incompetent. Another older dataset features Fascist magazine writing about social groups, articles content analyzed and recreating the SCM space (31).

Generalizing to Subtypes

Most SCM studies address stereotypes of societal groups, after asking pilot participants to identify the relevant ones. Subtypes reproduce the SCM space, differentiating by warm and competence different kinds of women and men (32), gay men (33), lesbians (34), African Americans (16, 35), immigrants (36), Muslims (37), and Native Americans (38). Subtypes of mental illness also spread out across the warmth-by-competence space (39).

Generalizing to Specific Groups

Drilling down to stereotypes of specific group, the SCM predicts the patronizing attitudes and behavior toward working mothers (40), sexualized women (41), and older people (13). The SCM also predicts the devaluing of lower-status people generally (42).

The SCM likewise describes patterns of resentment toward (enviable) Asians in the U.S. (15), Americans in other countries (43, 44), and politicians everywhere (45). Other enviable outgroup members (rich people, business people) specifically elicit envy-consistent Schadenfreude (malicious glee at their misfortunes), measured by self report, smile-muscle activation, and neural reward centers (46, 47).

Disgusting outgroup members (homeless, drug addicted) elicit not only reports of disgust, but also insula activation consistent with those reports (48). Moreover, participants report dehumanizing responses, such as being disinclined to imagine the minds and experiences of such individuals, and the neural areas (e.g., mPFC) implicated in such judgments likewise fail to activate.

Generalizing to Individuals

As noted, warmth and competence apply to individual person perception, as well as group perception. In a specific test of SCM predictions at the individual level, higher status individuals were expected to be competent, and competitive individuals were expected to be not warm (49). The status expectations cause higher status people to compensate for their apparent lack of warmth and lower-status individuals to compensate for their apparent lack of competence (50). Cross-racial interactions parallel these status effects (51, 52).

Generalizing to Other Intent-having Entities

If the primary warmth judgment reflects perceived intent for good or ill, and perceived competence reflects the capacity to enact that intent, then other entities seen as possessing intent should fit the warmth-by-competence space. Indeed, animals spread out across the space, with dog and cats appearing high on both, and vermin appearing low on both. Predators are competent but cold and edible farm animals are nice but stupid (53).

Organizations of people, such as corporations, also appear to have intent, and the public responds according with trust only for apparently well-intentioned brands and respect only for competent ones that deliver (54, 55).

Causality among the SCM Variables

Most SCM studies are descriptive and correlational, so the structure-stereotype-prejudice-behavior sequence rests on correlations consistent with predictions (7, 16). Experiments directly manipulating interdependence and status structures for two hypothetical groups do yield the predicted patterns of warmth and competence stereotypes (56). As noted, manipulated interdependence and status between two individuals show the same effects on perceived warmth and competence traits (49). Similarly, manipulating status alone (by housing price) predicts the inhabitants’ expected competence (57).

Likewise, manipulating apparent warmth and competence in vignette studies leads to the predicted emotions (56). These emotions mediate the link between stereotypes and behavior (16).

Dynamics between the Dimensions: Compensation and Innuendo

Warmth and competence themselves often correlate negatively, contrary to halo-effect predictions (58, 59), especially in comparative contexts (60, 61), and regardless of direct or indirect measurement (62; see 63, for a review).

Lay people understand and use these tradeoffs in communicating stereotypes. They will mention the positive dimension and not mention the negative one, knowing that innuendo will imply it, a phenomenon dubbed stereotyping by omission (2), which allows stereotypes to stagnate over time. Listeners understand the innuendo (64), and impression-managers likewise use it, downplaying one dimension to emphasize the other (65).

Moderators

Individual and Group Moderators

Although not much tested, some individual difference variables moderate how much people endorse the SCM model. Status-justifying ideologies reinforce the status-competence correlation (57).

Group-level moderators include group membership. Slight ingroup favoritism emerges for students rating students, across nations, and for countries rating themselves, within the EU (29). Groups especially favor themselves on their stronger dimension, higher status groups on competence and lower-status groups on warmth (66); strength of group identification affects interpretation of outgroup behavior on SCM dimensions (67).

Individual and group-level moderators of the warmth dimension and its correlation with interdependence have been even less evident. Cooperative or competitive orientations are likely candidates. Morality might also be relevant, because warmth includes morality and trustworthiness. Suggestive support comes from preliminary work on system legitimacy (21).

Cultural and Macro Moderators

Cultural differences emerged immediately, as East Asian samples demoted societal ingroups and reference groups to the middle of SCM space, consistent with cultural modesty norms (68).

More broadly, the central feature of the SCM space is the warmth-by-competence differentiation of groups, in which the two dimensions are roughly orthogonal. To the extent the two dimensions correlate, they boil down to a single vector of evaluation. Cross-cultural samples from every populated continent indicate that the SCM space does differentiate groups, but that the warmth-competence correlation varies (20, 68). Countries with more income inequality show less warmth-competence correlation, indicating that they use the ambivalent (mixed) quadrants; these and related data suggest justifying inequality (some high-status groups are allegedly nice and some not; some low-status groups are allegedly deserving and some not). Under income equality, most groups locate in the acceptably medium to high-high space and qualify for social benefits; the extreme low-low outgroups (homeless, nomadic, migrant) do not.

Another macro dimension that apparently affects use of the warmth-competence space is conflict (43). Higher-conflict countries adopt more of an us-them cultural map, minimizing use of the ambivalent parts of the space. (See 69 for a more detailed review of cultural patterns.)

Conclusion

For the past 15 years, the stereotype content model has accumulated evidence that warmth and competence differentiate social groups in more that three dozen countries, over time, and at levels of analysis that include subtypes and individuals. Perceived social structures of competition and status predict the two dimensions, which together predict distinct emotional prejudices and discriminatory tendencies. Moderators appear at the individual, group, cultural, and macro level, but many of the patterns are consistent: Citizens and the middle class are admired as high on both dimensions; unhoused people such as migrants, homeless, and nomads disgust as low on both. Older and disabled people are pitied as well intentioned but incompetent. Rich and business people are envied as competent but cold. These patterns occur in self-reports and neural signature.

Ongoing work addresses specific groups’ profiles (e.g., older people: 14, 70). Future work could address combinations of groups across the space. Also, individual differences in endorsing the SCM space might be of interest, as would be moderators of its use.

Highlights.

Two fundamental dimensions -- warmth and competence -- explain stereotyping, as the Stereotype Content Model shows.

The model identifies ambivalent stereotypes of respect but not liking or of liking but not respect.

Perceived social structure (competition, status) predicts these stereotypes, which in turn predict distinct emotional prejudices (envy, disgust, pity, pride), which then predict distinct discriminatory tendencies.

SCM principles generalize across dozens of cultures, decades of time, and levels from neural response to social interaction to cultural ideology.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Department of Justice, the Russell Sage Foundation, and Princeton University for funding the research reported here.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Katz D, Braly K. Racial stereotypes of one hundred college students. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1933;28:280–290. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bergsieker HB, Leslie LM, Constantine VS, Fiske ST. Stereotyping by omission: Eliminate the negative, accentuate the positive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(6):1214–1238. doi: 10.1037/a0027717. Shows stereotype content over the 20th century.

- 3.Gilbert GM. Stereotype persistence and change among college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1951;46:245–254. doi: 10.1037/h0053696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlins M, Coffman TL, Walters G. On the fading of social stereotypes: Studies in three generations of college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1969;13:1–16. doi: 10.1037/h0027994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Boston: Addison-Wesley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiske ST. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of social psychology. 4th. Vol. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 357–411. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from the perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:878–902. First major theoretical and empirical statement of the SCM.

- 8. Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P. Universal dimensions of social perception: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2007;11:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005. Prior review of SCM research to date.

- 9.Asch SE. Forming impressions of personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1946;41:1230–1240. doi: 10.1037/h0055756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abele AE, Wojciszke B. Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93(5):751–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojciszke B, Bazinska R, Jaworski M. On the dominance of moral categories in impression formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:1245–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glick P, Fiske ST. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuddy AJC, Norton MI, Fiske ST. This old stereotype: The pervasiveness and persistence of the elderly stereotype. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:265–283. [Google Scholar]

- 14. North MS, Fiske ST. An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138(5):982–997. doi: 10.1037/a0027843. Reviews ageism research and derives an intergroup threat model consistent with the SCM default for older people.

- 15.Lin MH, Kwan VSY, Cheung A, Fiske ST. Stereotype content model explains prejudice for an envied outgroup: Scale of Anti-Asian American Stereotypes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:34–47. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631. The original statement of discriminatory behavioral tendencies that follow from the SCM.

- 17.Fiske ST, Xu J, Cuddy AJC, Glick P. (Dis)respecting versus (dis)liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. Journal of Social Issues. 1999;55:473–491. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kervyn N, Fiske ST, Yzerbyt Y. Foretelling the primary dimension of social cognition: Symbolic and realistic threats together predict warmth in the stereotype content model. Social Psychology. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000219. (in press) Develops the prediction of warmth from interdependence.

- 19.Willis J, Todorov A. First impressions: making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychological Science. 2006;17:592–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Durante F, Fiske ST, Kervyn N, Cuddy AJC, Akande A, Adetoun BE, Adewuyi MF, Tserere MM, Al Ramiah A, Mastor KA, Barlow FK, Bonn G, Tafarodi RW, Bosak J, Cairns E, Doherty S, Capozza D, Chandran A, Chryssochoou1 X, Iatridis T, Contreras JM, Costa-Lopes R, González R, Lewis JI, Tushabe G, Leyens J-Ph, Mayorga R, Rouhana NN, Smith Castro V, Perez R, Rodríguez-Bailón R, Moya M, Morales Marente E, Palacios Gálvez M, Sibley CG, Asbrock F, Storari CC. Nations’ income inequality predicts ambivalence in stereotype content: How societies mind the gap. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2013;52:726–746. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12005. A macro variable, income inequality, predicts warmth-competence correlations.

- 21.Oldmeadow JA, Fiske ST. Contentment to resentment: Variation in stereotype content across status systems. Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2012;12(1):324–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2011.01277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talaska CA, Fiske ST, Chaiken S. Legitimating racial discrimination: A meta-analysis of the racial attitude-behavior literature shows that emotions, not beliefs, best predict discrimination. Social Justice Research: Social Power in Action. 2008;21:263–296. doi: 10.1007/s11211-008-0071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH. The measurement of meaning. Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kervyn N, Fiske ST, Yzerbyt Y. Integrating the Stereotype Content Model (warmth and competence) and the Osgood Semantic Differential (evaluation, potency, and activity) European Journal of Social Psychology. 2013;43:673–681. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg S, Nelson C, Vivekananthan PS. A multidimensional approach to the structure of personality impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9:283–294. doi: 10.1037/h0026086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wojciszke B. Multiple meanings of behavior: construing actions in terms of competence or morality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:222–232. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander MG, Brewer MB, Hermann M. Images and affect: a functional analysis of out-group stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:78–93. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phalet K, Poppe E. Competence and morality dimensions in national and ethnic stereotypes: A study in six eastern-European countries. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1997;27:703–723. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. Competence and warmth as universal trait dimensions of interpersonal and intergroup perception: The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 40. New York: Academic; 2008. pp. 61–149. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fiske ST, North MS. Social psychological measures of stereotyping and prejudice. In: Boyle GJ, Saklofske DH, Matthews G, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological constructs. Oxford, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2014. Reviews psychometrics of the SCM, among other measures of social bias.

- 31.Durante F, Volpato C, Fiske ST. Using the Stereotype Content Model to examine group depictions in Fascism: An archival approach. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;40:465–483. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eckes T. Paternalistic and envious gender stereotypes: Testing predictions from the stereotype content model. Sex Roles. 2002;47:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clausell E, Fiske ST. When do the parts add up to the whole? Ambivalent stereotype content for gay male subgroups. Social Cognition. 2005;23:157–176. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brambilla M, Carnaghi A, Ravenna M. Status and cooperation shape lesbian stereotypes. Social Psychology. 2011;42(2):101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiske ST, Bergsieker H, Russell AM, Williams L. Images of Black Americans: Then, “them” and now, “Obama!”. DuBois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2009;6:83–101. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X0909002X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee TL, Fiske ST. Not an outgroup, not yet an ingroup: Immigrants in the Stereotype Content Model. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2006;30:751–768. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saud L, Fiske ST. 2015 Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burkley E, Andrade A, Durante, & Fiske ST. 2014 Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiske ST. Warmth and competence: Stereotype content issues for clinicians and researchers. Canadian Psychologist/Psychologie Canadienne. 2012;53(1):14–20. doi: 10.1037/a0026054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. Journal of Social Issues. 2004;60:701–718. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cikara M, Eberhardt JL, Fiske ST. From agents to objects: Sexist attitudes and neural responses to sexualized targets. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23:540–551. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cikara M, Farnsworth RA, Harris LT, Fiske ST. On the wrong side of the trolley track: Neural correlates of relative social valuation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5:404–413. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durante F, Fiske ST, Gelfand M, Stillwell A, et al. More conflict? Less ambivalence! Societal stereotypes across nations. 2014 Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glick P, Fiske ST, Abrams D, Dardenne B, Ferreira MC, Gonzalez R, et al. Anti-American sentiment and America’s perceived intent to dominate. An 11-nation study. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2006;28(4):363–373. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fiske ST, Durante F. Never trust a politicians? Collective distrust, relational accountability, and voter response. In: van Prooijen J-W, van Lange PAM, editors. Power, politics, and paranoia: Why people are suspicious about their leaders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2014. pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cikara M, Botvinick MM, Fiske ST. Us versus them: Social identity shapes neural responses to intergroup competition and harm. Psychological Science. 2011;22:306–313. doi: 10.1177/0956797610397667. Shows neural reward activation to the misfortunes of competitors, correlated with self-reports of past aggression.

- 47. Cikara M, Fiske ST. Stereotypes and Schadenfreude: Behavioral and physiological markers of pleasure at others’ misfortunes. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012;3:63–71. doi: 10.1177/1948550611409245. Shows EMG measures of smile muscles upon reading misfortunes of envied outgroups.

- 48. Harris LT, Fiske ST. Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: Neuro-imaging responses to extreme outgroups. Psychological Science. 2006;17:847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x. Shows deactivation of neural areas implicated in social cognition, uniquely in response to pictured homeless people and drug addicts.

- 49.Russell AM, Fiske ST. It’s all relative: Social position and interpersonal perception. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:1193–1201. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swencionis J, Fiske ST. Promote up, ingratiate down: Status comparisons drive warmth-competence tradeoffs in impression management. (under review) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bergsieker HB, Shelton JN, Richeson JA. To be liked versus respected: Divergent goals in interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(2):248–264. doi: 10.1037/a0018474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dupree C, Fiske ST. Missing each other’s boat: Divergent self-presentation of warmth and competence in inter- vs. intra-group settings. (in preparation) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sevillano V, Fiske ST. Animal collective: Social perception of animals. (under review) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kervyn N, Fiske ST, Malone C. Brands as intentional agents framework: Warmth and competence map brand perception, Target Article. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2012;22:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malone C, Fiske ST. The human brand: How we relate to people, products, and companies. San Francisco: Wiley/Jossey Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caprariello PA, Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST. Social structure shapes cultural stereotypes and emotions: A causal test of the stereotype content model. Group Processes and Intergroup Behavior. 2009;12:147–155. doi: 10.1177/1368430208101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oldmeadow J, Fiske ST. Ideology moderates status = competence stereotypes: Roles for Belief in a Just World and Social Dominance Orientation. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2007;37:1135–1148. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Judd CM, James-Hawkins L, Yzerbyt VY, Kashima Y. Fundamental dimensions of social judgment: Understanding the relations between competence and warmth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:899–913. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.899. Original statement of trade-offs between the SCM dimensions.

- 59.Yzerbyt VY, Kervyn N, Judd CM. Compensation versus halo: The unique relations between the fundamental dimensions of social judgment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:1110–1123. doi: 10.1177/0146167208318602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kervyn N, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. You want to appear competent? Be mean! You want to appear sociable? Be lazy! Group differentiation and the compensation effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:363–367. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kervyn N, Yzerbyt VY, Demoulin S, Judd CM. Competence and warmth in context: The compensatory nature of stereotypic views of national groups. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:1175–1183. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kervyn N, Yzerbyt VY, Judd CM. When compensation guides inferences: Indirect and implicit measures of the compensation effect. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;41:144–150. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kervyn N, Yzerbyt VY, Judd CM. Compensation between warmth and competence: Antecedents and consequences of a negative relation between the two fundamental dimensions of social perception. European Review of Social Psychology. 2010;21:155–187. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kervyn N, Bergsieker HB, Fiske ST. The innuendo effect: Hearing the positive but inferring the negative. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2012;48(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Holoien DS, Fiske ST. Downplaying positive impressions: Compensation between warmth and competence in impression management. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2013;49:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.09.001. Shows impression managers de-emphasizing one SCM dimension to emphasize the other.

- 66.Oldmeadow JA, Fiske ST. Social status and the pursuit of positive social identity: Systematic domains of intergroup differentiation and discrimination for high and low status groups. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2010;13:425–444. doi: 10.1177/1368430209355650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Richetin J, Durante F, Mari S, Perugini M, Volpato C. Primacy of warmth versus competence: A motivated bias? The Journal of Social Psychology. 2012;152:417–435. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2011.623735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Kwan VSY, Glick P, Demoulin S, Leyens J-Ph, Bond MH, Croizet J-C, Ellemers N, Sleebos E, Htun TT, Yamamoto M, Kim H-J, Maio G, Perry J, Petkova K, Todorov V, Rodríguez-Bailón R, Morales E, Moya M, Palacios M, Smith V, Perez R, Vala J, Ziegler R. Stereotype content model across cultures: Towards universal similarities and some differences. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;48:1–33. doi: 10.1348/014466608X314935. Cross-cultural validation of the SCM.

- 69.Fiske ST, Durante F. Stereotype content across cultures: Variations on a few themes. In: Gelfand MJ, Chiu C-Y, Hong Y-Y, editors. Advances in Culture and Psychology. Vol. 6. New York: Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 70.North MS, Fiske ST. Act your (old) age: Prescriptive, ageist biases over succession, identity, and consumption. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2013;39(6):720–734. doi: 10.1177/0146167213480043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]