BACKGROUND

Child maltreatment represents a highly deleterious influence on the mental health and development of children (1-5). It is preventable (6,7) and yet alarmingly prevalent (8), affecting 1 in 8 U.S. children. While maltreatment at any age can lead to adverse outcomes, maltreatment in early childhood is associated with particular insults to cognitive and social emotional development as well as serious physical risk (9, 10). Early maltreatment has been shown to be particularly deleterious with respect to enduring patterns of emotion regulation, social relatedness, and executive functioning (11, 12).

Tragically in the U.S., studies have found the likelihood that a child placed in foster care for child abuse or neglect will experience maltreatment recidivism following reunification with his/her birth parents is between 30 and 37% (13). The sentinel event of placement of a young child in protective custody for child maltreatment represents a critical opportunity for preventive intervention. In a large administrative-data study of chronic, official-report child abuse or neglect, Jonson-Reid and colleagues (14) showed that children who experienced a single episode of official-report maltreatment—but no further occurrences—incurred rates of mental health care utilization that were not significantly elevated over that of children in the general population. This study exhibited a dose-response relationship between number of official reports of child maltreatment (over 2) and adverse psychiatric outcomes.

Interventions to stabilize and enhance the outcomes of children in foster care include those that focus on a) the quality of the foster care environment; b) decision-making about reunification; and/or c) support of birth parents (in the event of reunification). Regarding (a) (quality of the foster care environments), Kessler et al. (2008) (15) demonstrated significant reductions in adult psychopathology among foster care alumni (primarily school-aged) who had been enrolled in a model case management program in which their case managers had higher levels of training and lower caseloads than was the case for care-as-usual. The outcomes of other efforts to enhance the foster caregiving environment, for example via multidimensional treatment foster care, a wrap-around multimodal intervention for foster families of children and adolescents with challenging behavior, have been promising but mixed (16, 17).

Over a decade ago, Zeanah and colleagues (10) reported on the naturalistic results of a Family Court collaboration with an academic division of child psychiatry (Tulane University, New Orleans, LA), focused primarily on the other two domains of intervention: (b) decision-making, and (c) support of birth families, during the period of infancy and early childhood. The program responded to a long-recognized need to assist courts and social services systems with the appraisal of the unique mental health needs of children in this age range. The Tulane model was organized around the integration of skilled child psychiatric assessment, dyadic intervention to promote parent-child attachment, and parental psychiatric care (whenever necessary or appropriate). It reduced (by over half) the occurrence of maltreatment recidivism in comparison to a matched group of children who did not receive the intervention. This reduction appeared attributable both to an overall reduction in the rate of reunification and to enhanced mental health support of families rendered by the clinical team during the reunification process and ensured by court provisions after reunification occurred.

To our knowledge, these important findings have never been replicated among young children in foster care, or even attempted, although similar comprehensive intervention strategies have been implemented with considerable success for young children at risk (i.e. before a documented instance of child abuse or neglect have occurred). Four years ago, our group secured continuous local government funding for a quasi-replication of the Tulane model in St. Louis County, Missouri, entitled the SYNCHRONY Project. Here we describe this court-based intervention as a psychiatric prototype of two-generation intervention which has recently been strongly advocated in early childhood policy recommendations (18-20), but for which there is a pressing need for more scientific data. We report our experience with children initially enrolled in the first thirty months of program implementation (January 2011-June 2013), and summarize the progress of the children (through March 2015) in the context of government data for the most recent historic cohort of 300 children in the same age range who were placed in protective custody prior to the launch of the SYNCHRONY Project, and whose cases had been closed by the St. Louis County Family Court at the time of this program analysis. We hypothesized that, in comparison to the historic cohort, children enrolled in the SYNCHRONY (SY) Project would be selected for higher-than-average risk but would demonstrate a comparable or lower maltreatment recidivism rate and shortened total time in foster care. Furthermore, among SY enrollees, we hypothesized that serial standardized measurements of a) the quality of parent-child relationships and b) the adaptive functioning of the children would steadily improve over the course of intervention.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Analyses for this initial program evaluation included comparisons of key sample characteristics between the SYNCHRONY Project cohort (SY), and the historic cohort (HC). Within SY, individual-level data was examined with respect to time-rated change in systematically-acquired outcome measures (see below). This program evaluation was reviewed by the Human Research Protection Office of the Washington University School of Medicine, and fell into the category of “non-research” in that it was restricted to use of existing, de-identified, clinically-acquired program data and public records.

Sample

The SYNCHRONY Project

Strengthening Young Children by Optimizing Family Support in Infancy

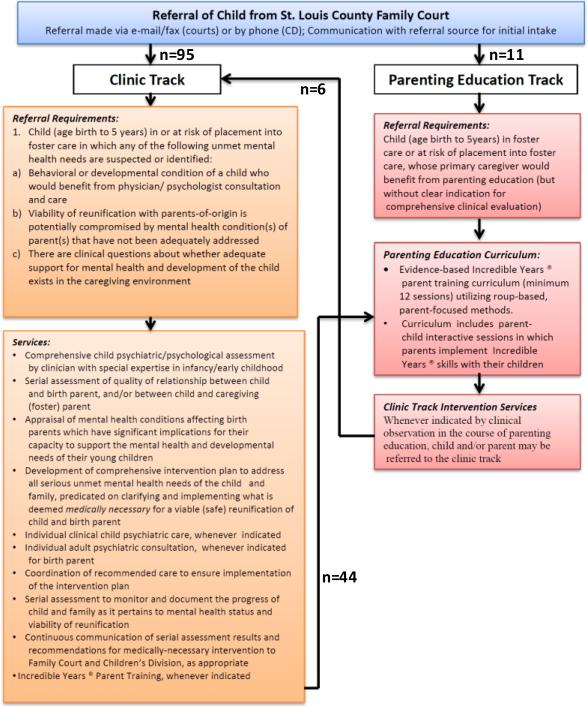

(SY) was launched in 2011 through funding from a locally-implemented children's services sales tax (the St. Louis County Children's Service Fund, http://keepingkidsfirst.org). Families of young children (age birth through 5 years) placed in foster care under the jurisdiction of the Family Court of Saint Louis County for child abuse or neglect were referred by the Court for voluntary participation in the program in one of two referral tracks, as illustrated in Figure 1—decision to refer and choice of referral track were made by deputy juvenile officers of the court assigned to the children's cases. Eighty-one per cent of referred families ultimately enrolled in the program. Track 1 was a comprehensive clinical track, in which the goal was to specify and resolve suspected unmet mental health needs of children or their birth parents through the provision of comprehensive mental health support. This included two-generation assessment and intervention planning, judicious referral for clinical services indicated by the assessment, direct clinical care whenever clinically-indicated services were not available in the community, and evidence-based parenting education (implementing the Incredible Years model). Track 2 was a “parenting education-only” track, however Track 2 families were transferred to Track 1 if mental health needs arose or became evident during the course of parenting education (this was common). This is a report on 119 young children in 106 families (first enrolled January 2011-June 2013), whose flow through the program is summarized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Referral of Children to the SYNCHRONY Project From the St. Louis Family Court

An Historic Cohort

(HC) was assembled from summary statistics on infants and toddlers whose STL County child abuse/neglect cases were closed prior to the launch of SY in 2011. This information, which may be used for governmental reporting and monitoring of service delivery, was available in aggregate only (no individual-level data) from the Court. Upon initial review of the most recent set of 300 cases, it was evident that 53 of the HC children had been placed in foster care exclusively for drug-exposure-in utero (DEIU). Such infants were never referred to SY unless there was an alternate primary reason for placement in protective custody. Therefore, DEIU infants were removed from the HC group for purposes of comparison, leaving aggregate data on 247 children to serve as a contrast group.

Table 1a summarizes selected characteristics of the SYNCHRONY and historic cohorts.

Table 1a.

Selected characteristics of clients, segregated by cohort and case status (SY-C: Closed SYNCHRONY cases versus SY-O: Open SYNCHRONY cases). All Historic Cohort (HC) cases were closed.

| HC (n=247 children) | SY-C (n=62 children from 49 families) | SY-O (n=57 index children from 57 families) | p HC vs SY-C | p SYC vs SY-O* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race Proportion Caucasian (%) |

0.31 | 0.32 | 0.33 | n.s | n.s |

| Gender Proportion female (%) |

0.48 | 0.43 | 0.32 | n.s | n.s |

| Major allegation Proportion physically abused |

0.21 | 0.24 | 0.05 | n.s | n.s |

| Prior history of adjudication | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 | n.s |

| History of being homeless* | 0.16 | 0.1 | n.s | ||

| History of employment* | 0.51 | 0.4 | n.s | ||

| History of TANF* | 0.18 | 0.21 | n.s | ||

| Caregiver history of parent in foster care* | 0.18 | 0.10 | n.s | ||

| History of domestic violence* | 0.35 | 0.22 | n.s | ||

| History of substance abuse* | 0.2 | 0.17 | n.s | ||

| History of mental health* | 0.41 | 0.28 | n.s | ||

| Mother had drug problems while participating in the program | 0.08 | 0.02 | n.s | ||

| History of crime arrest* | 0.47 | 0.35 | n.s | ||

| Caregiver did parent ED* | 0.31 | 0.32 | n.s | ||

| Caregiver finished parent ED* | 0.22 | 0.3 | n.s | ||

| Father years of school* | M=12.0 | M=11.0 | n.s | ||

| Mother years of school* | M=11.0 | M=12.0 | n.s | ||

| History of employment time* | M= 2.0 | M= 1.6 | n.s | ||

| Number of children in the family* | M= 2.4 | M= 2.2 | n.s | ||

| Family income* | M= 3.6 | M= 3.7 | n.s | ||

| Child age in months at referral* | M=37.3 | M=37.1 | n.s | ||

| Mother age in years at referral* | M=25.8 | M=27.8 | n.s | ||

| Father age in years at referral* | M=27.6 | M=31.4 | n.s |

Denotes analyses conducted for open (n=57) and closed (n=49) SY cases, with family as unit of comparison

Two-Generation Psychiatric Assessment

The program's two-generation assessment (TGA) systematically included: a) evaluation of the child; b) ascertainment of characteristics of the parent-child relationship (historic and observed) that were relevant to the viability of reunification; c) clinical screening for mental health conditions of birth parent(s) that would have implications for the safety and viability of reunification; and d) the development of a comprehensive plan for supplemental behavioral health / developmental intervention for the family.

Comprehensive Intervention Planning

The development of a comprehensive set of recommendations for “value-added” clinically-indicated intervention—i.e. supplemental intervention that was not already being received by the family at the time of referral—was a primary endpoint of TGA. For any given family, these recommendations generally fell into one or more of the following general categories: (A) parent-child psychotherapy / family therapy; (B) specific revision of the visitation schedule; (C) child individual therapy (psychotherapy or developmental therapy); (D) child psychopharmacologic treatment; (E) adult psychiatric treatment.

In all cases, recommendations were communicated to the Court and the Department of Social Services, and whenever medically-indicated services (A-E) of appropriate quality were not accessible to the family, they were provided by SY. Each family was subsequently seen quarterly (at a minimum) for assessment of clinical progress, titration of necessary mental health service, and documentation of medical judgment regarding the safety of reunification at each juncture. In most cases, the results of serial assessment comprised a critical evidentiary basis for the Court's decision-making regarding the appropriateness and viability of reunification.

Parenting Education (IY)

The SYNCHRONY Project Parenting Education program utilized the Incredible Years (IY) curriculum for toddlers (21), a 14-session group-based curriculum keyed to video vignettes that are viewed, discussed, and role-played by parents. The topics include positive parenting behaviors that reward and promote attachment, communication, self-regulation, and cooperation; these include listening, following a child's leads, praise, and descriptive commenting. In addition techniques for preventing and managing maladaptive behaviors in children are taught and rehearsed, including clarification of expectations, ignoring, and time-out. “Hands-on practice” sessions with the parents’ own children (whenever possible) supplemented the curriculum following every third session—these involved semi-structured play activities that could be re-implemented at home; these included sensory play for infants, symbolic interactive (puppet) play for toddlers, creative expression (finger paints), and the building of “blanket forts” to simulate safety, intimacy, and composure. Clinicians trained in IY were available to guide and support parents through these activities. Of the first 106 SY families, 55 actively participated in the parenting education curriculum; 39 “graduated” by attending 75% or more of the sessions.

Serial Measurement

Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), is a widely-implemented clinical rating scale used to document children's overall adaptive functioning; the normal range is 70-100 on a scale from 1 to 100. The instrument features descriptive scoring anchors which help ensure favorable psychometric properties (described extensively elsewhere, 22). CGAS was conducted serially by MD or PhD clinicians for all clinical track children age 4 and older, and exhibited test-retest correlation of 0.57 program-wide, supporting substantial reliability of the measurements.

Caregiver-Child Social Emotional Relationship Rating Scale (CCSERRS) is a brief standardized rating of the relational quality, used to measure the quality of interactions between children and their birth parents. Emotional availability of caregivers, mutuality of caregiver-child interactions, child and caregiver affect, and the extent to which a caregiver follows the lead of a child are scored according to highly descriptive scoring anchors validated in prior research (23). CCSERRS ratings were completed serially by licensed clinicians (MD, PhD, LCSW, or LPC). Intra class correlation for CCSERRS ratings for families serially observed in the parenting education curriculum was 0.52, supporting substantial test-retest reliability of the measurements.

Parenting Scale

The parenting scale is a 30-item self-report scale of parental discipline originally developed to assess the discipline practices of parents of preschool children (24). Parents indicate their tendencies to use specific discipline strategies using 7-point Likert scales, where 7 indicates a high probability of making a disciplinary error, and 1 indicates a high probability of using an effective, alternative discipline strategy. Factor analyses have revealed independent contributions of three components: overreactivity (authoritarian parenting style which include threats and physical punishment), laxness (characterizes a caregiver who is permissive and inconsistent when providing discipline), and verbosity (describes a caregiver who tends to give lengthy verbal reprimands, rather than taking direct action).

Results

Characteristics and Outcomes of the SYNCHRONY Cohort in relation to an Historic Cohort

Children enrolled in the SYNCHRONY Project were highly representative of historic St. Louis County populations of young children taken into court custody; the children were predominantly minority and neglected, with a slight preponderance of males over females. SYNCHRONY families (closed cases) were over three times more likely than the average family in the historic cohort to have had a prior history of adjudication in the family court, indicative of the unusually high level of risk that characterized the initial group of families referred to the program (see Table 1a—54% of SY families manifested at least two of the major risk factors presented in the table).

The three-fold higher rate of prior adjudication among SYNCHRONY families established an expectation of elevated rate of subsequent referral to the Children's Division for child abuse or neglect while in custody. Contrary to this expectation, there was no significant difference in rate of subsequent referral for child maltreatment between SY and HC families, consistent with a protective effect of SY. The rate of successful reunification in this high-acuity cohort (30%) was significantly lower than that for the HC cohort (53.8%, p<0.001). We note that the intended impact of the program involved both the support of successful reunifications and the prevention of unsafe reunifications. On average, children in SY experienced a shorter period between initial placement in protective custody and case closure.

Although it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which SY medical recommendations independently influenced court dispositions, we note the following: 1) the vast majority of SY medical recommendations for therapeutic support and modification of visitation parameters were supported by the Court; 2) the prevailing disposition (reunification versus guardianship or termination of parental rights) was reversed following SY referral in approximately one fifth of the cases; 3) since the inaugural year of the project, the STL County Family Court has continuously referred a majority of its non-DEIU preschool protective custody cases to SY.

Clinical Mental health needs identified and addressed by the SYNCHRONY Project

For all 106 enrolled SYNCHRONY cases, unmet mental health needs of either a) the children (untreated or inadequately addressed clinical developmental or behavioral problems), b) the parents (active untreated or inadequately-treated psychiatric diagnoses), and/or c) the parent-child relationship (inadequate access to high-quality parent education, non-viable visitation schedules) were identified. There were no cases in which there existed “no clinical indication” for the addition of one or more supplemental interventions in one or more of these categories, i.e. over and above care as usual being provided by the child welfare system. A majority of birth parents manifested mental health (see Table 1A), developmental, or substance use disorders—for most of these there were gaps in what would be considered standard treatment for these disorders, and 20% directly received adult psychiatric care in SY. Twelve per cent of the children were referred for individual psychotherapy (approximately half provided by SY), 33% were newly diagnosed with a developmental disorder for which developmental therapies (usually State-supported) were initiated, 10% received pharmacotherapy via SY, and 30% manifested clinical indications for family therapy (all provided by SY); in total 67% were recognized as being in need of one or more of these clinically-indicated interventions. In 9% of cases, initial recommendations included a substantive reduction in the frequency of visitation with birth parents; in 28% of cases, recommendations were made for a substantive increase in frequency of visitation. Case examples of the provision of supplemental interventions and the respective children's outcomes are briefly summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Case examples of the nature and impact of supplemental intervention in the SYNCHORONY project

| Case example | Domain of supplemental intervention over “CAU” | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 5 year old female, expressive language disorder, undiagnosed PTSD | Child individual psychotherapy (TF-CBT) | Resolution of PTSD, marked improvement in adaptive functioning |

| 1 year old battered child with subdural hematoma, developed manifestations of severe autistic syndrome | Developmental Therapy | Initiated early intensive behavioral intervention which was accompanied by steady gains in developmental capacity for social communication |

| 4 year old male with Neurofibromatosis Type 1, severe ADHD, unmanageable in high-quality preschool environment | Child psychopharmacologic treatment | Stimulant treatment: marked improvement in preschool behavior and facilitation of kindergarten readiness |

| 3 year old female witnessed protracted rage episode of father, who was presumed to be intractably dangerous | Adult psychiatric treatment | Borderline personality disorder diagnosed, comprehensive intervention initiated, safety plan established, visitation liberalized, family reunified |

| 2 year old female placed with maternal aunt, birth mom living in close proximity and intruding on foster placement, threatening SIB | Family Therapy | Boundaries and strict visitation schedule established, birth mom treated with pharmacotherapy followed by family therapy--family successfully reunified |

| 3 year old male with language delay presumed secondary to neglect, but discovered by SY to be attributable to chromosomal rearrangement | Parenting Education | Markedly improved parenting skills, liberalization of visitation, successful reunification |

| 5 year old male with severe anxiety discovered secondary to factitious disorder by proxy, maternal delusional disorder | Specific revision of visitation schedule | Identification of unrecognized delusional disorder averted planned reunification, parental rights terminated, child adopted |

Results of serial assessment of children within the SYNCHRONY Project

Over the course of the families’ enrollment, CGAS scores steadily improved over the course of the intervention, irrespective of the timing of enrollment of the child in the program relative to the timing of his/her placement in protective custody (which varied from days to years across cases, as shown in Table 2, such that the observed improvement of the cohort would be inconsistent with an exclusive effect of regression toward the mean). On average, over the time from baseline evaluation to the most recent available follow-up, the change in CGAS scores for children in the program was 8.15 (t (90) = 5.66, p<0.001), which is highly clinically and statistically significant representing an approximate effect size of 0.6. This improvement occurred, on average, irrespective of whether or not children were ultimately reunified with their birth parents.

Table 2.

Course of CGAS and CCSERRS for selected groupings of subjects tracked within the SYNCHRONY Project

| Measurement | Sample | N pre-post tests available | Sig. | Baseline M (SD) | Post-test M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGAS | |||||

| All cases | 91 | 0.001 | 60.7 (15.78) | 68.85 (13.58) | |

| Closed cases | 43 | 0.001 | 60.6 (13.78) | 66.84 (13.6) | |

| Serial CCSERRS | |||||

| Closed cases not reunified | 22 | 0.09 | 17.6 (5.4) | 15.38 (5) | |

| Closed cases reunified | 19 | 0.05 | 17.71 (4) | 19.58 (3.8) | |

| IY Parenting Scale | |||||

| All cases | 28 | 0.001 | 4.11 (0.99) | 3.17 (0.92) | |

| Open cases | 17 | 0.004 | 4.25 (0.91) | 3.16 (0.99) | |

| Closed cases | 11 | 0.039 | 3.89 (1.12) | 3.17 (0.85) |

Among cases closed to date, the trends for CCSERRS scores were reflective of ultimate disposition: among closed cases who were reunified with birth parents, CCSERRS scores significantly improved from baseline to the most recent available measurement. In this group, most of the parents attended evidence-based parent training, most graduated, and the improvement in CCSERRS scores were observed over the course of the time they participated in parent training (p<0.046). In contrast, among closed cases who were not reunified, an opposite picture emerged: CCSERRS ratings exhibited a trend for deterioration over the course of the families’ involvement in the program (see Table 2). Many were non-compliant with parent-training, attended infrequently, and few graduated. Incredible Years (IY) Parenting Scale self-report test scores revealed baseline levels of verbosity, laxness, and over-reactivity consummate with published means for parents of school-aged children with disruptive behavior disorders enrolled in IY clinical trials; verbosity scores improved significantly as detailed in Table 2.

Conclusions

In this voluntary support program, two-generation psychiatric care and evidence-based parenting education were successfully delivered to families of young children in protective custody to supplement care-as-usual in the child welfare system and to offset risk for maltreatment recidivism. Such services were in very short supply and their delivery was minimally-reimbursed by Medicaid. As first observed by Zeanah et al. (2001) (10), this St. Louis quasi-replication was readily accepted by most families (who were often but not always highly motivated by the prospect of reunification with their children), embraced collaboratively by both the Family Court and Department of Social Services, and resulted—for the vast majority of cases—in the delivery of medically-indicated services that had otherwise not been implemented in the course of usual care. SYNCHRONY (SY) Project parents made substantial gains from severely abnormal baseline scores on the Incredible Years Parenting scale, and children made substantial gains from abnormal baseline scores on clinical assessments of adaptive functioning, irrespective of the timing of enrollment relative to the date of placement in protective custody. Abuse recidivism has been extremely low to date, and has remained low for children who have been successfully reunified with their parents. To deliver medically-indicated care and to integrate that care with the work of the child welfare system, this program required government subsidy over and above Medicaid reimbursement rates on the order of $1500 per child per year.

The positive outcomes that were observed occurred in some cases as a function of intensified support of families over the course of the reunification process, and in other cases as a function of serial clinical observations which raised warning signs that an impending reunification was unsafe and should be deferred until one or both birth parents could reasonably demonstrate capacity to meet the needs of their children's mental health and development (examples of both are provided in Table 3). Regarding the latter, such observations were communicated to the Court and often led to higher levels of surveillance by both the Courts and the Missouri Department of Social Services. When cross-system observation consistently revealed an inability of birth parents to meet critical needs of their children, and exhaustive attempts (across systems) to remedy the observed risks failed, the clinical observations of SY could ultimately lead to a recommendation of termination of parental rights as the mechanism by which maltreatment recidivism was averted.

Ultimately it would require randomized controlled trials of court-based implementation of two-generation psychiatric care to precisely ascertain the magnitude (and cost efficacy) of improvement-in-outcome over care-as-usual conferred by this supplemental program. We note, however, that such trials are extremely difficult to conduct feasibly in the setting of the immediate aftermath of placement of a young child in protective custody. Approaching young parents who have lost custody of their children to engage in research in which they would be randomized to mental health support could be construed as highly ethically inappropriate, and the randomization of children in protective custody would require consent from the State (their legal guardian) to enroll them in randomized controlled trials. This inherent difficulty with more rigorous study designs strongly motivates our reporting of this promising open trial in an effort to contribute to an evidentiary base for more appropriate allocation of U.S. government resources, in favor of targeted intervention for the mental health support of children and families indexed (by the event of placement in protective custody) for extreme high risk for one of the most deleterious known environmental causes of child psychopathology, which is recurrent child maltreatment.

Table 1b.

Selected outcomes of clients, segregated by cohort and case status.

| HC | SYC | SYO | P HC v. SYC | P HC v. SYO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPR filed | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.37* | n.s | n.s |

| Proportion reunified | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.001 | ||

| Avg. # days from opening referral to closure | 739 (aggregate) | 673 | |||

| Subsequent adjudication | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 | n.s | n.s |

| Subsequent referrals | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.14 | n.s | n.s |

Cases were still open at time of analysis, and disposition can change prior to case closure.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support for the intervention program provided by the St. Louis County Children's Service Fund and a philanthropic gift from an anonymous donor to the Washington University School of Medicine. We acknowledge also the extraordinary efforts of the clinical team who collaborated with the authors in implementing the program, including Ann McAndrew LPC, Molly McGrath MSW, Jennifer Holzhauer MSW, Megan Panther MBA, Caroline Wheatley MSW, Lara Oakley, Sandy Polanc, Laura Pons MSW, Angela Klocke RN, and a succession of resident physicians in training who assisted the authors in delivering the clinical interventions. We acknowledge our dedicated colleagues in the St. Louis County Family Court, including Carol Bader JD, Kip Seely, and Michael Burton JD, and our colleagues in the Missouri Department of Social Services whose partnership made the program possible. Finally we acknowledge those parents and caregivers of children in the program, including birth parents, foster parents, and small villages of devoted family members, who rose to the occasion of the crises involving the young children enrolled, faithfully (usually very patiently) engaged in the intervention process, and inspired the members of our intervention team.

Contributor Information

John Nicholas Constantino, Washington University School of Medicine - Child Psychiatry, 660 S. Euclid Avenue Campus Box 8134, St. Louis, Missouri 63110.

Vered Ben-David, Washington University - School of Social Work, St. Louis, Missouri.

Neha Navsaria, Washington University School of Medicine - Psychiatry, St. Louis, Missouri.

Eric Spiegel, Washington University School of Medicine - Psychiatry, 4560 Clayton Ave CID Building Suite 1000, St. Louis, Missouri 63110.

Anne Laurence Glowinski, Washington University School of Medicine - Psychiatry, 4560 Clayton Ave CID Building Suite 1000, St. Louis, Missouri 63110.

Cynthia Rogers, Washington University School of Medicine - Psychiatry, 4560 Clayton Ave CID Building Suite 1000, St. Louis, Missouri 63110.

Melissa Jonson-Reid, Washington University - School of Social Work, St. Louis, Missouri.

References

- 1.Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Kohl P. Is the overrepresentation of the poor in child welfare caseloads due to bias or need? Child Youth Serv Rev. 2009;31:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cicchetti D, Rogosh FA, Toth SL, et al. Normalizing the development of cortisol regulation in maltreated infants through preventive interventions. Dev Psychopathol. 2011;23:789–800. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, et al. Attachment and security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Dev Psychopathol. 22:87–108. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M, Gunnar MR, et al. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on daytime cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:892–905. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selph SS, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Nelson HD. Behavioral interventions and counseling to prevent child abuse and neglect: a systematic review to update the US Preventive services task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):179–190. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knerr W, Gardner F, Cluver L. Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Prev Sci. 2013;14(4):352–363. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, et al. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putnam-Hornstein E. Report of maltreatment as a risk factor for injury death: A prospective birth cohort study. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16:163–174. doi: 10.1177/1077559511411179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeanah CH, Larrieu JA, Heller SS, et al. Evaluation of a preventive intervention for maltreated infants and toddlers in foster care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(2):214–221. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowell RA, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, et al. Childhood maltreatment and its effect on neurocognitive functioning: Timing and chronicity matter. Dev Psychopathol. 2015;27(2):521–533. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeanah CH, Fox A, Nelson CA. Attachment relationships in the context of severe deprivation: the Bucharest early intervention project. Bulletin. 2013;1(63):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonson-Reid M. Foster care and future risk of maltreatment. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2003;25(4):271–294. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connell CM, Vanderploeg JJ, Katz KH, Caron C, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Maltreatment following reunification: Predictors of subsequent Child Protective Services contact after children return home. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(4):218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonson-Reid M, Kohl PL, Drake B. Child and adult outcomes of chronic child maltreatment. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):839–845. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Pecora PJ, William SJ, et al. Effects of enhanced foster care on the long-term physical and mental health of foster care alumni. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(6):625–633. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leve LD, Kerr DC, Harold GT. Young Adult Outcomes Associated with Teen Pregnancy Among High-Risk Girls in an RCT of Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2013;22(5):421–434. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2013.788886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green JM, Biehal N, Roberts C, et al. Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Adolescents in English care: randomised trial and observational cohort evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(3):214–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shonkoff JP, Fisher PA. Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2013;22(5):421–434. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegenthaler E, Thomas M, Matthias E. Effect of preventive interventions in mentally ill parents on the mental health of the offspring: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Presnall N, Webster-Stratton CH, Constantino JN. Parent training: equivalent improvement in externalizing behavior for children with and without familial risk. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(8):879–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyrborg J, Warborg LF, Nielsen S, Byman J, Buhl NB, Gautre-Delay F. The Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) and Global Assessment of Psychosocial Disability (GAPD) in clinical practice—substance and reliability as judged by intraclass correlations. European Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s007870070043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCall RB, Groark CJ, Fish LE. A Caregiver–Child Socioemotional and Relationship Rating Scale (CCSERRS). Infant Ment Health J. 2012;31:201–219. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold DS, O'Leary SG, Wolff LS, Acker MM. The Parenting Scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychol Assess. 1993;5:137–144. [Google Scholar]