Abstract

Visceral basidiobolomycosis is an unusual fungal infection of viscera caused by saprophyte Basidiobolus ranarum. It is very rare in healthy children and poses a diagnostic challenge due to the non-specific clinical presentation and the absence of predisposing factors. We report a case of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in a 4-year-old healthy girl who presented with a short history of abdominal pain, bleeding per rectum, fever, and weight loss. The diagnosis was based on high eosinophilic count, classical histopathology findings of fungal hyphae (the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon), and positive fungal culture from a tissue biopsy. Fungal infection was successfully eradicated with a combined approach of surgical resection of the infected tissue and a well-monitored course of antifungal therapy. The atypical clinical presentation, diagnostic techniques, and the role of surgery in the management of a rare and lethal fungal disease in an immunocompetent child are discussed.

Key words: Basidiobolomycosis, child, fungal infection, gastrointestinal, immunocompetent

INTRODUCTION

Basidiobolomycosis is a potentially lethal and rare fungal infection caused by environmental saprophyte Basidiobolus ranarum, a member of the order Entomophthorales of the class zygomycetes. The zygomycetes include two fungal orders: Mucorales, which involve only the immunocompromised patients, and Entomophthorales, which causes infection in immunocompetent individuals.[1,2,3,4]

Basidiobolomycosis is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Latin America, Middle East, and Asia.[5,6] The exact mode of transmission of saprophyte B. ranarum is not understood but it is postulated that B. ranarum on vegetation and organic debris is consumed by insects and other arthropods, which in turn are devoured by frogs, lizards, and other animals. These animals then disseminate the fungus and infect other animals and humans. Basidiobolomycosis usually involves the exposed parts of the body, but visceral involvement and systemic lesions have also been reported.[5,7,8,9]

Visceral basidiobolomycosis (VB) is very rare in healthy humans and to date only 71 cases have been reported in the English Literature.[5,10] The diagnosis can be mystifying due to its poorly understood clinical presentation and predisposing risk factors. We report an immunocompetent young child with VB, who proffered a diagnostic and management challenge and benefited from a combination of surgery and antifungal therapy. We discuss the atypical clinical presentation, diagnosis, and the role of the surgeon in the management of this rare disease. This is a first case report from our institute and country.

CASE REPORT

A 4-year-old girl was admitted with a short history of vague abdominal pain, bleeding per rectum and weight loss. Her general and systemic examination was unremarkable. She underwent for a full set of investigations to look for the cause of her bleeding per rectum. Colonoscopy revealed ulcerated mucosa in the left colon and the lumen was incompletely occluded by an extraluminal mass. Her colonic biopsies were inconclusive. In view of the patient was undergoing evaluation, she developed abdominal distention, vomiting, and high-grade fever (40°C), and laboratory results showed prominent eosinophilia, high white cell counts, and negative blood culture. Ultrasound revealed a retroperitoneal heterogenous ill-defined mass and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed patchy areas of diffusion restriction on apparent diffusion coefficient map denoting areas of evolving liquefaction and circumferential peripheral enhancement on the gadolinium-enhanced T1 images suggesting a phlegmon formation which was encasing left colon, left ureter, and the vessels [Figure 1]. The patient was taken for emergency exploratory laparotomy, which revealed a mass in the left abdomen involving and compressing the left colon, extending towards the midline and very densely adherent with surrounding structures including retroperitoneal vessels and left ureter. It was inflammatory in nature and contained multiple microabscesses [Figure 2]. A tissue biopsy was taken for further evaluation and proximal faecal diversion with a transverse colostomy was performed to overcome the intraluminal obstruction. The post-operative course was uneventful, and histopathology showed granulomatous necrotising inflammation along with fungal hyphae (the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon), which was consistent with basidiobolomycosis [Figure 3]. Fungal culture from excised tissue was also positive for basidiobolomycosis. Based on these findings, patient was started on voriconazole 7 mg/kg (VFEND, Pfizer Manufacturing Deutschland GmbH) every 12 h and kept under close observation by regular monitoring of cardiac, visual, and liver functions at regular intervals. The patient showed recovery from illness and was continued on oral antifungal therapy along with monitoring of cardiac, visual, and liver functions. Three months later, a repeat set of radiological images showed a regression of the phlegmonous mass along with a reduction in the thickness of left colon wall. After 9 months, her radiological studies showed persistent VB involving left colon but there was a marked reduction in the size. The further surgical intervention was carried out along with removal of VB by resection and anastomosis of the diseased bowel segment. The histopathology of the resected colon showed persistent fungal hyphae (the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon), however, the margins of the resected bowel were clear. Two-month later, MRI of the abdomen revealed no residual mycosis and patent bowel lumen, hence, the reversal of colostomy was performed followed by discontinuation of antifungal therapy (total duration 12 months). The patient has been in regular follow-up with our multidisciplinary team for last 14-month and has remained asymptomatic.

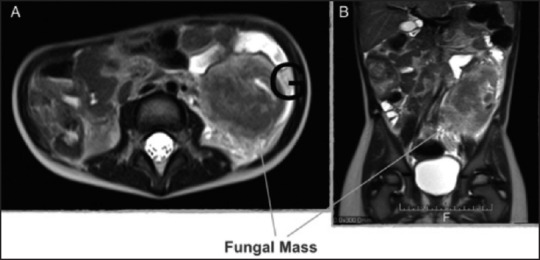

Figure 1.

MRI before surgical intervention and antifungal treatment: T2 weighted axial cross (A) and Sagittal (B) sections showing a large retrocolic heterogenous mass predominantly hypointense, indiscernible from the descending colon, with surrounding high signal in the retroperitoneal fat

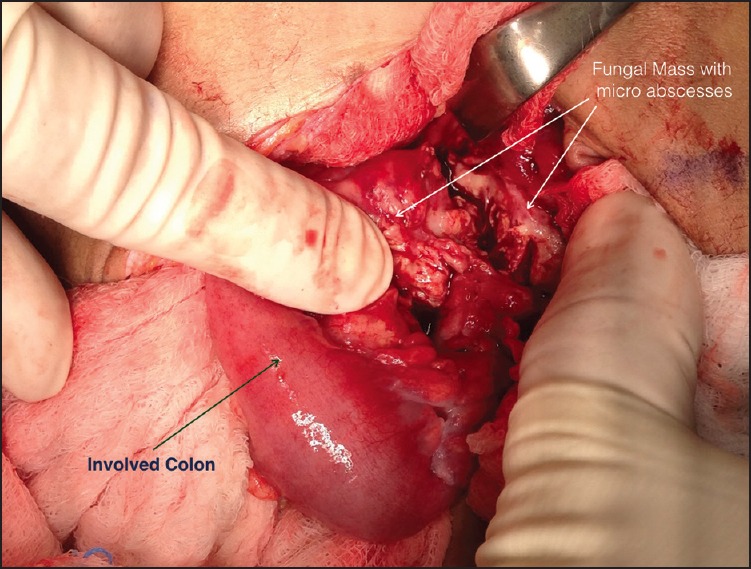

Figure 2.

Operative findings showing oedematous left colon surrounded by an inflammatory mass containing microabscesses

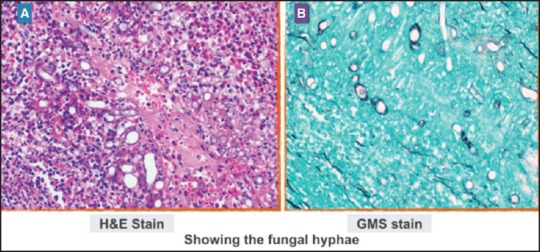

Figure 3.

H and E (a) And Gomori's methenamine silver staining (b) Of the tissue biopsy from left retrocolic mass showing the presence of Splendore-Hoeppli bodies and many eosinophils, as well as intensely radiating eosinophilic granular material, surrounding the fungal elements ([a] ×20 and [b] ×40)

DISCUSSION

Since the first reported case of VB in 1964, 71 cases of VB have been reported, which consists of 23 cases from Saudi Arabia, 23 from USA, 17 from Iran, 6 from Iraq, 2 from Kuwait, and 1 from the Netherlands. The patient's age ranged from 18 months to 80 years, and the disease was significantly more common in males (65 Males and 6 females). Of these, 71 cases, 28 (39%) were children.[5,6,7,8] Ours is the first case report of VB (involving colon) in an immunocompetent patient from a country that has been diagnosed and managed successfully.

The clinical manifestations of childhood VB are vague and include abdominal pain, fever, vomiting, loose stools, and weight loss leading to a misperception in diagnosis as occurred in our case. Delay in the diagnosis of intra-abdominal basidiobolomycosis has been reported with high morbidities such as bowel perforations, fistula formations, and fulminating sepsis leading to death.[7,11,12] In our case, the child presented with a short history of vague abdominal symptoms and evaluation with radiology and colonoscopy to reach the diagnosis was inconsistent. We considered VB as one of the differential diagnosis based on the atypical clinical picture, high eosinophilic counts in the blood results, and inconclusive histopathology of colonoscopic biopsies even though it very difficult for the clinicians to think about a fungal infection in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of a completely healthy child.

The diagnosis of basidiobolomycosis is based on characteristic histopathology findings of fungal hyphae (the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon) and culture of B. ranarum from the tissue specimen. B. ranarum involves the non-mucosal layers such as submucosa and subserosa of the GI tract, hence endoscopic biopsies, which are superficial and small, usually fail to detect the fungal hyphae and remain inconclusive.[13] In our case, the histopathological examination of endoscopic biopsy specimens showed non-specific inflammation. The granulomatous inflammation that extended deep into the layers of colonic wall demonstrated classical fungal hyphae, which provided initial diagnosis supported later by the culture of B. ranarum. This highlights the importance of deep tissue biopsies from the lesion to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The management of VB involves surgery and antifungal treatment for a variable period of time (6 months to 2 years) to eradicate the disease and prevent an early recurrence.[6,7,13] In the reported cases in the literature, due to inconsistent clinical and radiological picture, patients have undergone for emergency surgery to have a total or near total surgical resection of the mass followed by a diagnosis of basidiobolomycosis and a course of antifungal medications such as amphotericin B, itraconazole, and voriconazole for a varied period of time.[5,6,7,14] Unlike these reported cases, in our patient, the diagnosis was suspected from the atypical clinical picture, eosinophilia, non-conclusive colonic biopsies, and radiological images. However, to reach a definitive diagnosis, surgical intervention was mandatory. After diagnosis, the child was started on antifungal medication under close observation, but the disease was persistent, after 9 months of therapy. Further surgical intervention with complete resection of the diseased viscera was performed after the patient had recovered from the acute illness and also when the inflammatory mass was significantly reduced after a course of antifungal therapy. Hence, a combination of well-planned surgical approach and well-monitored course of antifungal therapy proved to be the best management option in our case by avoiding major surgical morbidity and drug-related adverse effects in a young child.

CONCLUSION

VB is rare and aggressive fungal disease in a paediatric population of tropical and subtropical regions. It usually presents atypically, hence it should be included as one of the differential diagnosis in children with abdominal sepsis. Surgical biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis and disease is cured effectively with surgical resection and a course of antifungal therapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Ms. Hanan Farghaly (Pathology Department), Dr. Mohammad Janahi, and Dr. Mariam Mansouri (Pediatric Department) to contribute for clinical care of this patient.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carr EJ, Scott P, Gradon JD. Fatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis that invaded the postoperative abdominal wall wound in an immunocompetent host. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:956–7. doi: 10.1086/520482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrabarti A, Chatterjee SS, Das A, Panda N, Shivaprakash MR, Kaur A, et al. Invasive zygomycosis in India: Experience in a tertiary care hospital. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:573–81. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.076463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi HL, Shin YM, Lee KM, Choe KH, Jeon HJ, Sung RH, et al. Bowel infarction due to intestinal mucormycosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;83:325–9. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2012.83.5.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohta A, Neogi S, Das S. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis in an infant. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:664–5. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.85149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Qahtani SM, Alsuheel AM, Shati AA, Mirza NI, Al-Qahtani AA, Al-Hanshani AA, et al. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in children. Curr Pediatr Res. 2013;17:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Shanafey S, AlRobean F, Bin Hussain I. Surgical management of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:949–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Jarie A, Al-Mohsen I, Al-Jumaah S, Al-Hazmi M, Al-Zamil F, Al-Zahrani M, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1007–14. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000095166.94823.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Shabrawi MH, Kamal NM. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in children: An overlooked emerging infection? J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(Pt 7):871–80. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.028670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vikram HR, Smilack JD, Leighton JA, Crowell MD, De Petris G. Emergence of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in the United States, with a review of worldwide cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1685–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geramizadeh B, Heidari M, Shekarkhar G. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis, a rare and under-diagnosed fungal infection in immunocompetent hosts: A review article. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;40:90–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Shabrawi MH, Kamal NM, Jouini R, Al-Harbi A, Voigt K, Al-Malki T. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: An emerging fungal infection causing bowel perforation in a child. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(Pt 9):1395–402. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.028613-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zavasky DM, Samowitz W, Loftus T, Segal H, Carroll K. Gastrointestinal zygomycotic infection caused by Basidiobolus ranarum: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1244–8. doi: 10.1086/514781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Asmi MM, Faqeehi HY, Alshahrani DA, Al-Hussaini AA. A case of pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis mimicking Crohn's disease. A review of pediatric literature. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:1068–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arjmand R, Karimi A, Sanaei Dashti A, Kadivar M. A child with intestinal basidiobolomycosis. Iran J Med Sci. 2012;37:134–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]