Abstract

Background:

Oesophageal atresia is a neonatal emergency surgery whose prognosis has improved significantly in industrialised countries in recent decades. In sub-Saharan Africa, this malformation is still responsible for a high morbidity and mortality. The objective of this study was to analyse the diagnostic difficulties and its impact on the prognosis of this malformation in our work environment.

Patients and Methods:

We conducted a retrospective study over 4 years on 49 patients diagnosed with esophageal atresia in the 2 Paediatric Surgery Departments in Dakar.

Results:

The average age was 4 days (0-10 days), 50% of them had a severe pneumonopathy. The average time of surgical management was 27 h (6-96 h). In the series, we noted 10 preoperative deaths. The average age at surgery was 5.7 days with a range of 1-18 days. The surgery mortality rate is 28 patients (72%) including 4 late deaths.

Conclusion:

The causes of death were mainly sepsis, cardiac decompensation and anastomotic leaks.

Key words: Esophageal atresia, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

Oesophageal atresia is a rare malformation with a prevalence of 2.43 per 10,000 births.[1] After surgery, the survival rate is about 90% if there are associated abnormalities and about 100% in isolated forms.[2,3] In sub-Saharan Africa, mortality is still high, raising several questions about the management of oesophageal atresia.[4] The goal of our study was to analyse the diagnostic difficulties and its impact on the prognosis of this malformation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a 4-year retrospective study (2010-2013) based on the records of patients born with esophageal atresia. The patient's profile, medical history, physical findings, laboratory and surgical treatment results were analysed.

RESULTS

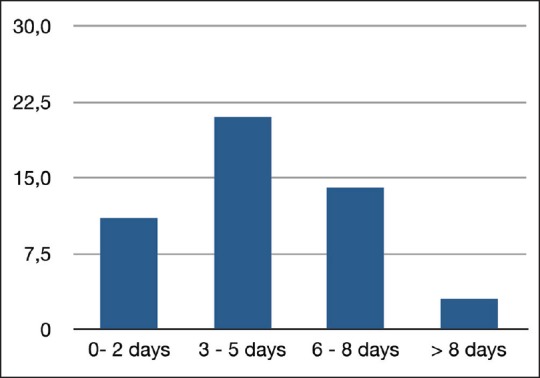

There were 49 newborns, including 31 boys and 18 girls, with an average age of 4 days (range: 0-10 days) [Figure 1]. The average birth weight (BW) was 2100 g (range: 1000 g - 3200 g). None of the patientss was diagnosed prenatally. Prenatal ultrasound performed in 41 patients showed hydramnios (7) and intrauterine growth delay (4). There were 14 premature deliveries, 4 before 34 weeks and 2 before 30 weeks. One of the patients products of twin pregnancies, the other twin was normal. The main features at presentation were hypersalivation and respiratory distress [Table 1]. Attempted passage of nasogastric tube got arrested at about 8-10 cm in 44 patients. Plain X-rays of the chest and abdomen in all patients showed the level of the proximal oesophageal pouch located at the second, third or fourth thoracic vertebra. Five patients needed trans-tube instillation of gastrografin to confirm the diagnosis and to determine the level of the proximal oesophageal segment. Associated anomalies were dominated by heart defects and anorectal malformation [Table 2]. Twenty four patients had severe pneumonia on admission. Surgery closure of the tracheo-oesophageal fistula and primary oesophageal anastomosis) was performed on 39 patients. The average age at surgery was 5.7 days with a range of 1-18 days. Thirty eight patients had type III atresia while one had type I of atresia. Three patients with anorectal anomally had with colostomy at the same sitting. Intra-operative complications included pleura tear (14), rib fractures (2), and one case of death. All patients were managed in the Intensive Care Unit on intravenous crystalloids. Enteral (trans nasogastric tube) feeding is introduced on the 5th day post-operative on average (range: 3 - 8 days) with gradual increase in the rate on the following days. Gastrographin swallow was performed between the 7th and 10th post-operative days with a nasogastric tube in place to rule out the absence of anastomotic leakage and major oesophageal stenosis before starting oral feeding. There were 11 anastomotic leaks including 4 early (first post-operative day), 2 reccurrence of the tracheo-esophageal fistula and 3 oesophageal stenoses. All the patients developed thrombocytopenia with moderate to severe anaemia. The surgery-related mortality rate was 72% (28 patients). The causes of death were mainly sepsis, cardiac decompensation and anastomotic leaks [Figure 2]. Three patients developed severe enterocolitis after introduction of enteral feeding of breast milk with 100% mortality rate. The average follow-up was 22 months (14-40 months).

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients according to the age of admission

Table 1.

Main symptoms

| Symptoms | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Hyper-salivation | 34 (69) |

| Respiratory distress | 20 (40) |

| Bronchial congestion | 21 (42) |

| Regurgitation | 12 (24) |

| Cyanosis | 6 (12) |

| Abdominal bloating | 2 (4) |

Table 2.

Associated anomalies with oesophageal atresia

| Associated malformations | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cardiac | 14 (28) |

| Anorectal malformation | 3 (6) |

| Choanal atresia | 2 (4) |

| Bilateral cryptorchidism | 1 (2) |

| Right inguinal hernia | 1 (2) |

| Craniofacial dysmorphia | 1 (2) |

Figure 2.

Causes of operative mortality in the short-term

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of oesophageal atresia is often done during prenatal screening nowadays.[4] The progress made in medical imaging field, the monitoring of high-risk pregnancies and biological analyses of amniotic fluids have permitted early diagnosis. The morphological ultrasound in third trimester and sometimes the foetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) done by qualified specialists have clearly increased the chances to visualise the absence of the continuity of the oesophagus associated with hydramnios and/or a small or missing stomach. The key is an ultra-early diagnosis (18 weeks of amenorrhea) and hydramnios (a late sign most often occurring after 24 weeks of gestation).[5,6,7] Diagnosis by prenatal ultrasound relies on indirect signs (hydramnios and/or small or invisible stomach) and direct signs (dilated proximal oesophagus or ‘pouch sign’).[6,8] The positive predictive value of the combination of these two signs (hydramnios and invisible or small stomach) is low, between 40% and 56%, with many false-positives;[9,10,11], while the combination (hydramnios and invisible or small stomach) and a dilated proximal esophageal segment (’pouch sign’) is between 60% and 100% with 80% and 100% sensitivity.[8,10,12] The MRI improves the sensitivity and specificity of the prenatal screening.[13,14]

The lack of esophageal continuity induces digestive enzymes changes such as gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and proteins in amniotic fluid during the 18th week of gestation.[15] These biological changes allow for the diagnosis of oesophageal atresia with 98% sensitivity and 100% specificity, regardless of the anatomic type.[5]

The absence of prenatal diagnosis in our study was due, to a lack of local expertise needed for the monitoring of suspected pregnancies. The hydramnios may have foetal digestive origin in <10%, whereas other causes may be maternal or placental.[16,17] Oesophageal atresias are responsible for a hydramnios in 95% of cases in the absence of fistula and 35% in the presence of distal fistula.[16] The finding of hydramnios should should arouse suspicion necessitating ultrasound from the 22nd week after gestation. Biological analysis of the amniotic fluid is a suitable option to consider. The creation of advanced prenatal screening units and the establishment of multidisciplinary meetings could optimise the management of oesophageal atresia. The prenatal diagnosis allows for in utero transfer of the foetus and the management to a destined birthplace for an expert management.[18]

All of our cases were diagnosed after birth with an average time quite long compared to the literature.[5,18] Often the clinical signs are enough to make the diagnosis; the additional tests are usually needed to establish the type of anatomical variant of oesophageal atresia and associated malformations. Proximity of maternity centers with the Pediatric Medical Surgery facilities, and improvement of collaboration between the various stakeholders who care for mothers and children could significantly shorten the time of diagnosis. The morbidity related to the delay of diagnosis is accentuated by the attempts to feed, thus causing a high rate of preoperative sepsis and pneumonia in our studies. The rate of associated malformation in this study agrees with earlier studies, with a predominance of cardiac abnormalities.[19,20,21,22]

Generally, there was a delay in the surgical intervention in this study, largely due to unavailability of preoperative investigations in emergency setting. This is unlike other studies that reported intervention period is of about 48 h.[5,18] The closure of the tracheo-esophageal fistula and primary oesophageal anastomosis is the reference technique with good outcome, as was our experience in this study.[23,24] However, staged operation is advisable in long gap defects (>3 vertebrae), while waiting for the spontaneous growth of the two oesophageal segments in 6-8 weeks. Corrective surgery can then be done by oesophageal anastomosis or by use of a gastric and intestinal transplant subsequently.[24,25]

Morbidity in our study was mainly caused by sepsis and anastomotic leaks. Koivusalo et al.[26] Reported that the longer the defect, the greater the risks during the anastomosis. This also causes gastro-esophageal reflux and oral feeding difficulties.[26] Other studies reported that the two main factors for survival are BW over 1500 g and the absence of associated cardiac abnormalities [Table 3].[27,28]

Table 3.

Mortality according to the classification of Spitz

| Classification | Number | Operative death | Non-operative death | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spitz A (BW >1500 g, without major CD) | 29 | 15 | 05 | 09 |

| Spitz B (BW <1500 g or major CD) | 15 | 10 | 03 | 02 |

| Spitz C (BW <1500 g and major CD) | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

BW: Birth weight; CD: Cardiac disease

In our study, mortality caused by sepsis was high especially in patients with a weight <1500 g and an isolated form of oesophageal atresia. This mortality may be directly related to the delay in diagnosis that increased the risk of severe pneumopathies caused by gastric fluid reflux into the lungs when saliva is inspirated and attempts to feed.

CONCLUSION

Oesophageal atresia is a neonatal emergency and life-threatening. Diagnostic delay increases the preoperative morbidity and makes the post-operation more complicated to manage. Thus, early diagnosis, the time for a surgery and the quality of post-operative intensive care determine the results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pedersen RN, Calzolari E, Husby S, Garne E EUROCAT Working group. Oesophageal atresia: Prevalence, prenatal diagnosis and associated anomalies in 23 European regions. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:227–32. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saing H, Mya GH, Cheng W. The involvement of two or more systems and the severity of associated anomalies significantly influence mortality in esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1596–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilja HE, Wester T. Outcome in neonates with esophageal atresia treated over the last 20 years. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:531–6. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2122-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandré E, Niandolo KA, Wandaogo A, Bankolé R, Mobiot ML. Oesophageal atresia: Management in Sub Saharian countries. Arch Pediatr. 2010;17:300–1. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garabedian C, Vaast P, Bigot J, Sfeir R, Michaud L, Gottrand F, et al. Esophageal atresia: Prevalence, prenatal diagnosis and prognosis. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2014;43:424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brantberg A, Blaas HG, Haugen SE, Eik-Nes SH. Esophageal obstruction-prenatal detection rate and outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:180–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centini G, Rosignoli L, Kenanidis A, Petraglia F. Prenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia with the pouch sign. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:494–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shulman A, Mazkereth R, Zalel Y, Kuint J, Lipitz S, Avigad I, et al. Prenatal identification of esophageal atresia: The role of ultrasonography for evaluation of functional anatomy. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:669–74. doi: 10.1002/pd.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Has R, Günay S. Upper neck pouch sign in prenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;270:56–8. doi: 10.1007/s00404-002-0463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langer JC, Hussain H, Khan A, Minkes RK, Gray D, Siegel M, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia using sonography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:804–7. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.22965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sparey C, Jawaheer G, Barrett AM, Robson SC. Esophageal atresia in the northern region congenital anomaly survey, 1985-1997: Prenatal diagnosis and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:427–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malinger G, Levine A, Rotmensch S. The fetal esophagus: Anatomical and physiological ultrasonographic characterization using a high-resolution linear transducer. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:500–5. doi: 10.1002/uog.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garabedian C, Verpillat P, Czerkiewicz I, Langlois C, Muller F, Avni F, et al. Does a combination of ultrasound, MRI, and biochemical amniotic fluid analysis improve prenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia? Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:839–42. doi: 10.1002/pd.4376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochart V, Verpillat P, Langlois C, Garabedian C, Bigot J, Debarge VH, et al. The contribution of fetal MR imaging to the assessment of oesophageal atresia. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:306–14. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3444-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller C, Czerkiewicz I, Guimiot F, Dreux S, Salomon LJ, Khen-Dunlop N, et al. Specific biochemical amniotic fluid pattern of fetal isolated esophageal atresia. Pediatr Res. 2013;74:601–5. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaumoître K, Amous Z, Bretelle F, Merrot T, D’Ercole C, Panuel M. Prenatal MRI diagnosis of esophageal atresia. J Radiol. 2004;85(12 Pt 1):2029–31. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(04)97776-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stringer MD, McKenna KM, Goldstein RB, Filly RA, Adzick NS, Harrison MR. Prenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1258–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garabedian C, Sfeir R, Langlois C, Bonard A, Khen-Dunlop N, Gelas T, et al. Does prenatal diagnosis modify neonatal management andearly outcome of children with esophageal atresia type III? J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2015 Jan 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2014.12.004. pii: S0368-2315(14)00318-4. doi: 10.1016/j. jgyn.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiely EM, Curry JI, Spitz L. Esophageal atresia: Improved outcome in high-risk groups? J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:331–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitz L. Oesophageal atresia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mcheik JN, Levard G. Malformations Congénitales de L’oesophage. EMC, Gastro-entérologie, 9-202-A-15. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mcheik JN, Levard G. Pathologie Chirurgicale Congénitale de L’oesophage. EMC, Pédiatrie, 4-017-A-10. 2001:26. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seitz G, Warmann SW, Schaefer J, Poets CF, Fuchs J. Primary repair of esophageal atresia in extremely low birth weight infants: A single-center experience and review of the literature. Biol Neonate. 2006;90:247–51. doi: 10.1159/000094037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamza AF. Colonic replacement in cases of esophageal atresia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2009;18:40–3. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tannuri U, Maksoud-Filho JG, Tannuri AC, Andrade W, Maksoud JG. Which is better for esophageal substitution in children, esophagocoloplasty or gastric transposition? A 27-year experience of a single center. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:500–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koivusalo AI, Pakarinen MP, Rintala RJ. Modern outcomes of oesophageal atresia: Single centre experience over the last twenty years. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spitz L, Kiely EM, Morecroft JA, Drake DP. Oesophageal atresia: At-risk groups for the 1990s. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:723–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto T, Takamizawa S, Arai H, Bitoh Y, Nakao M, Yokoi A, et al. Esophageal atresia: Prognostic classification revisited. Surgery. 2009;145:675–81. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]