Abstract

Background:

Congenital epidermolysis bullosa (CEB) is a rare genodermatosis. The digestive system is very frequently associated with skin manifestations. Pyloric atresia (PA) and oesophageal stenosis (OS) are considered the most serious digestive lesions to occur. The aim of this work is to study the management and the outcome of digestive lesions associated to CEB in four children and to compare our results to the literature.

Patients and Methods:

A retrospective study of four observations: Two cases of PA and two cases of OS associated to CEB managed in the Paediatric Surgery Department of Fattouma Bourguiba Teaching Hospital in Monastir, Tunisia.

Results:

Four patients, two of them are 11 and 8 years old, diagnosed as having a dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa since the neonatal period. They were admitted for the investigation of progressive dysphagia. Oesophageal stenosis was confirmed by an upper contrast study. Pneumatic dilation was the advocated therapeutic method for both patients with afavourable outcome. The two other patients are newborns, diagnosed to have a CEB because of association of PA with bullous skin lesions with erosive scars. Both patients had a complete diaphragm excision with pyloroplasty. They died at the age of 4 and 3 months of severe diarrhoea resistant to medical treatment.

Conclusion:

Digestive lesions associated to CEB represent an aggravating factor of a serious disease. OS complicating CEB is severe with difficult management. Pneumatic dilatation is the gold standard treatment method. However, the mortality rate in PA with CEB is high. Prenatal diagnosis of PA is possible, and it can help avoiding lethal forms.

Key words: Congenital epidermolysisbullosa, oesophageal stenosis, pyloric atresia

INTRODUCTION

Congenital epidermolysis bullosa (CEB) is a rare genodermatosis. It is classified into three major groups on the basis of the cleavage level with the cutaneous basement membrane zone: The simplex form (SEB), the junctional form (JEB) and the dystrophic form (DEB).[1]

The digestive system is very frequently associated with cutaneous manifestations of CEB. Pyloric atresia (PA) and oesophageal stenosis (OS) are the most important digestive lesions observed.

JEB is the most frequently associated group to PA whereas recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa Hallopeau–Siemens (RDEB-HS)type is the most frequently complicated with OS.[2,3]

The aim of this work is to study the management and outcome of digestive lesions associated to CEB in four observations and to compare our results to the literature.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study of four observations: Two cases of PA and two cases of OS associated to CEB managed in the Paediatric Surgery Department of Fattouma Bourguiba Teaching Hospital in Monastir, Tunisia.

Each patient had a physical examination with biological (blood count, urea, and creatininemia) and radiological explorations (Plain X-ray, abdominal ultrasonography and upper contrast study). A digestive fibroscopy was indicated for the patients with OS.

Observations

Case 1

An 11-year-old boy was diagnosed as having RDEB-HS in the neonatal period. He was admitted for investigation of progressive dysphagia to solids which started a year before. He has no pathologic familial history.

At physical examination, the patient was under-nourished with a weight of 20 kg (<3rd percentile), a height of 130 cm (−1.5 standard deviation [SD]) with a body mass index (BMI) of 11.83 (<3rd percentile).Numerous bullae and open weeping lesions were present particularly on traumatic points (hands, elbows, knees and feet). There was also syndactyly of fingers and toes with club-shaped hands and onychodystrophy with anonychy. He had bullae and scars of the mouth with tongue retraction and dystrophic teeth.

We noted iron deficiency anaemia with haemoglobin of 6.6 g/dl.

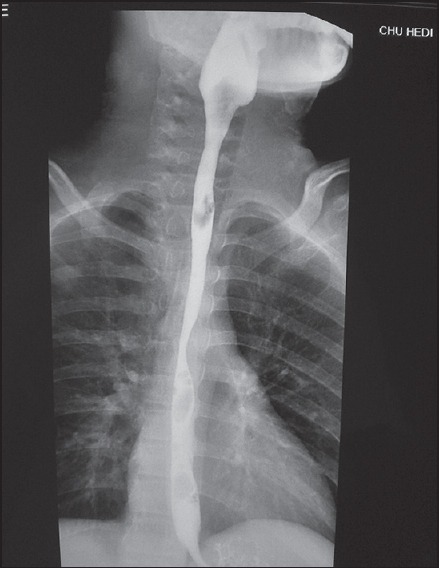

An upper contrast study completed with upper digestive fibroscopy confirmed OS localised 20 cm from the dental arch [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Upper contrast study oesophageal stenosis

The patient had three sessions of pneumatic dilations associated to local steroid infiltration (HSHC). Dilation sessions were done a month apart.

The initial outcome was relatively favourable with a partial regression of the stenosis (5-7 mm). An 8-year outcome was marked with a normal oral nutrition with weight gain. Upper contrast study (5 years after the last dilation session) showed a normal oesophagus diameter with a regular wall [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Upper contrast study normal oesophagus diameter with regular wall

Case 2

An 8-year-old boy diagnosed as having RDEB-HS in the neonatal period was admitted for dysphagia to liquids.

He has no pathological familial history. He was hospitalised at the age of 3 years for herpetic encephalitis with a favorable outcome.

Dysphagia started at the age of 2 years, with a progressive aggravation from dysphagia to solids to difficulties to swallow the saliva.

At physical examination, there was a severe growth retardation with a weight of 19 kg (<3rd percentile) and a height of 113 cm (−2 SD and −1 SD) and a BMI 14.96 (25th percentile); a huge haemorrhagic bulla was noticed in the left inguinal region with multiple dystrophic scars on face, neck and abdomen. There was poororo-dental hygiene with vesiculo-bullous lesions of the tongue and an onychodystrophy of big toes with partial scarring alopecia of the scalp. The biological investigation revealed a moderate iron deficiency anaemia with a haemoglobin of 11.5 g/dl.

An upper contrast study completed by an upper digestive fibroscopy confirmed the presence of 3 mm tight OS at the junction of the median — The inferior third of the oesophagus with dilation of the upper part.

The patient had two pneumatic dilations at a 2 months interval with local steroid infiltration hydrocortisone hemisuccinate (HSHC).

The outcome was favourable with the regression of the stenosis and disappearance of dysphagia. He had a moderate weight gain (9 kg in 4 years).

Case 3

A 4-day-old, full-term male was transferred to our department because of suspected congenital PA. He was a product of a normal vaginal delivery and had a birth weight of 2.35 kg with APGAR 9/10. The father and mother were second cousins.

Paternal ant has presented post-traumatic bullous lesions on her face.

Two paternal cousins operated for congenital PA. Both of them developed cutaneous bullous lesions and died shortly. After, it was attributed to CEB. No further etiologic explorations were made.

At birth, the patient presented post-prandial non-bile stained vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a Stage I dehydration, a left upper abdominal fullness, a right ectopic testis and a left clubfoot.

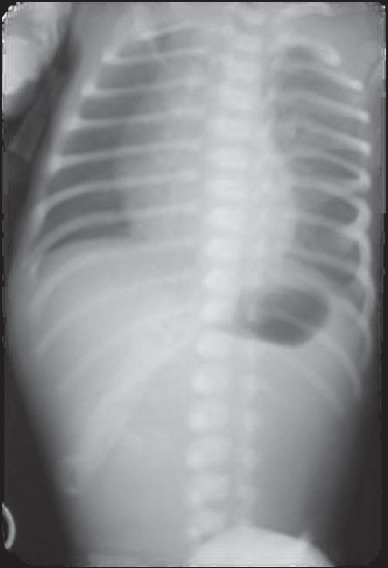

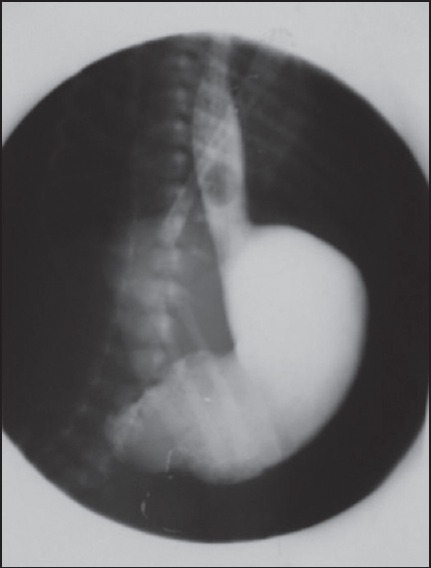

A plain abdominal-X-ray showed a dilated stomach. The rest of the abdomen was gasless [Figure 3]. An upper contrast study showed a gastric distension with no opacification of the bulb or the duodenum compatible with a PA [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Abdominal plain X-ray dilated stomach, the rest of the abdomen is gasless

Figure 4.

Upper contrast study gastric distension with no opacification of the bulb or the duodenum

After the correction of the dehydration, an abdominal exploration via laparotomy showed a complete antro-pyloric diaphragm (Type I PA). The patient had a complete excision of the diaphragm via a longitudinal incision with pyloroplasty.

At day 2 of hospitalization, the patient presented bullous skin lesions with erosive scars on the hypogastric region, dorsal side of the left foot and left elbow: Aspect advocating CEB. Skin biopsy of the affected zone was made for ultra structural examination, but no report was available.

Oral nutrition was introduced at day 5 of post-surgery with a good tolerance.

The patient was discharged at day 12 of post-surgery. He was hospitalised at the age of 3 months and a half for severe diarrhoea with dehydration which was attributed to a gastroenteritis resistance to medical treatment. The patient died 2 weeks after because of severe hemodynamic alterations.

Case 4

A 10-day-old, full-term male was transferred to our department because of suspected congenital PA. He was a product of a normal vaginal delivery and had a birth weight of 3.1 kg with APGAR 7/9. The father and mother were second cousins.

At day 3 of life, the patient presented post-prandial non-bile stained vomiting with weight loss.

Physical examination revealed the dehydration Stage II with weight loss (600 g) and a palpable stomach. No skin anomaly was noticed.

A plain abdominal-X-ray showed a dilated stomach, the rest of the abdomen was gasless. Abdominal ultrasonography eliminated pyloric hypertrophy stenosis.

An upper contrast study showed a gastric distension with opacification of the antro-pyloric region without opacification of the bulb and the duodenum advocating the diagnosis of PA.

After correction of the dehydration, an exploratory laparotomy showed a complete antro-pyloric diaphragm (Type I PA).

A complete diaphragm excision with pyloroplasty was practiced via a longitudinal incision opposite to the diaphragm.

At day 5 of hospitalisation, the patient presented bullous skin lesions with erosive scars on the abdomen, four limbs and the scalp: A spect advocating CEB [Figure 5]. Skin biopsy was not unfortunately done.

Figure 5.

Bullous skin lesions with erosive scars

Oral nutrition was introduced at day 6 of post-surgery with good tolerance.

The patient was discharged at day 15 post-surgery. He was hospitalized at the age of 3 months for severe diarrhoea with dehydration. The patient died of severe hemodynamic alterations.

DISCUSSION

CEB is a rare genodermatosis with a prevalence is estimated to 1/50,000 births.[4] In Tunisia, the prevalence varies between 8/100,000 and 12/100,000 births.[5] Its transmission can be either autosomal dominant or recessive.

Mucous membranes can be affected including the digestive system with bullae and ulcers complicating feeding and scarring may limit the mobility of the tongue. OS and PA are the two most frequent severe digestive lesions associated to CEB. OS is due to dystrophic cicatrisation of recurrent bullae and ulcerative lesions of an inflammatory mucosa.[6,7,8,9,10,11] This may lead to difficulty in maintaining adequate nutrition.[12]

The severity of digestive lesions is correlated with the group of CEB. DEB and particularly RDEB-HS is the group with the highest morbidity. OS complicates frequently RDEB-HS.[2,3] Its incidence is estimated to 20% of the patients with RDEB.[6] This incidence is 79.1% in RDEB-HS, 86.7% for flexural (inverse)-RDEB.[7,8]

OS in case of RDEB-HS occurs between the ages of 4 and 59 years with a mean age of 16 years.[9,10] The age of our two patients was respectively 11 and 8 years.

Chronic inflammation and ulcero-bullous lesions are caused by traumatism of the malpighian epithelium of the oesophagus mucosa by solid and hot food.[9,10] Food pressure exerted on the oesophagus opposite to the aorta cross and to the tracheal carina explains the frequent localization of the stenosis at the superior third of the oesophagus.[8,9,10] One of our two patients had the stenosis at the superior third of the oesophagus whereas the second was at the junction of the median and inferior thirds.

Diagnosis of stenosis is usually made byan upper contrast study. Digestive fibroscopy is a useful tool for stenosis confirmation but is not recommended because of the oesophageal and buccopharyngeal mucosafragility.[11]

Pneumatic dilation is the gold standard treatment of the oesophageal stenosis complicating RDEB.[9,11,13,14] However, oesophageal replacement is indicated in cases of pneumatic dilation failure.

PA can be associated to the majority of types of CEB and most frequently to the junctional group. This association is a heterogeneous disease with lethal forms that can lead to death within few months after birth despite surgical correction. This can be explained by diffuse lesions including both skin and mucosa.[15] Many criteria support an autosomal recessive transmission. It is generally revealed during the neonatal period, at the first feeding attempts.[16]

Prenatal diagnosis of PA by ultrasonography is possible. Anatomic stomach features can be studied from the 14th gestation week. Diagnosis is frequently based on the association of polyhydramnios with gastric enlargement.[17,18]

Clinical symptoms are non-bilious vomiting, respiratory distress, dehydration, and gastric distension. Gastric perforation can complicate PA. Diagnosis is based on abdominal plain X-ray and upper contrast study.[19]

Treatment consists of correction of dehydration and biological anomalies completed by an excision of the diaphragm with pyloroplasty. Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty is the most frequently used.[20]

After surgery, gentle stomach suction with parenteral nutrition is necessary before introducing a progressive enteral nutrition. A delay of enteral feeding is controversial.

The long-term prognosis of PA with CEB is characterised by high mortality rates which approximate 100% in spite of surgical correction.[21] It was the case of our two patients who died shortly after discharge.

Some authors reported genetic mutations of integrin beta4 (ITGB4) gene which codes for β4 integrin. This mutation is implicated in a severe form PA with diarrhea resistant to medical treatment.[22,23]

Though, a favourable outcome is reported in some cases of mild CEB with PA.[24]

A number of digestive manifestations associated to CEB are reported such as gastro-oesophageal reflux in SEB, constipation in DEB and exsudative enteropathy in JEB.[25]

CONCLUSION

Digestive lesions associated to CEB represent an aggravating factor of a serious disease. OS complicating RDEB-HS is severe with difficult management. Pneumatic dilatation is the gold standard treatment method. However, the mortality rate in PA with CEB is high particularly in the presence of ITGB4 mutation. Prenatal diagnosis of PA is possible, and it can help to avoid lethal forms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Research laboratory: LR 12SP13.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bello YM, Falabella AF, Schachner LA. Management of epidermolysis bullosa in infants and children. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:278–82. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(03)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agha FP, Francis IR, Ellis CN. Esophageal involvement in epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica: Clinical and roentgenographic manifestations. Gastrointest Radiol. 1983;8:111–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01948101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orlando RC, Bozymski EM, Briggaman RA, Bream CA. Epidermolysis bullosa: Gastrointestinal manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1974;81:203–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-81-2-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stavropoulos F, Abramowicz S. Management of the oral surgery patient diagnosed with epidermolysis bullosa: Report of 3 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:554–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.06.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaziri F. Oesophageal stenosis due to dystrophic epidermolysis of the child. Presentation of four cases and review of the literature. Thesis of medicine school of Tunis. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harmel RP., Jr Esophageal replacement in two siblings with epidermolysis bullosa. J PediatrSurg. 1986;21:175–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(86)80078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Suchindran C. Gastrointestinal complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: Cumulative experience of the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:147–58. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812f5667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine JD, Mellerio JE. Extracutaneous manifestations and complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: Part I. Epithelial associated tissues. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:367–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson SH, Meenan J, Williams KN, Eady RA, Prinja H, Chappiti U, et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic dilation of esophageal strictures in epidermolysis bullosa. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:28–32. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujimoto T, Lane GJ, Miyano T, Yaguchi H, Koike M, Manabe M, et al. Esophageal strictures in children with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: Experience of balloon dilatation in nine cases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:524–9. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azizkhan RG, Stehr W, Cohen AP, Wittkugel E, Farrell MK, Lucky AW, et al. Esophageal strictures in children with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: An 11-year experience with fluoroscopically guided balloon dilatation. J PediatrSurg. 2006;41:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milne B, Rosales JK. Anaesthesia for correction of oesophageal stricture in a patient with recessive epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica: Case report. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1980;27:169–71. doi: 10.1007/BF03007782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandgren K, Malmfors G. Balloon dilatation of oesophageal strictures in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998;8:9–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah MD, Berman WF. Endoscopic balloon dilation of esophageal strictures in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:153–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung HJ, Uitto J. Epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yandza T, Valayer J. Congenital malforrmations of the stomach. EMC pediatrics. 2005;2:277–86. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahebpoor AA, Ghaffari V, Shokoohi L. Pyloric atresia associated with epidermolysis bullosa: A report of 4 survivals in 5 cases. Iran J Pediatr. 2007;17:369–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizzo G, Capponi A, Arduini D, Romanini C. Prenatal diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux by color and pulsed Doppler ultrasonography in a case of congenital pyloric atresia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;6:290–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1995.06040290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasbi NA, Bellagha I, Hammou A. Neonatal occlusion. Imaging contribution. J Pediatr Pueric. 2004;17:112–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Søreide K, Sarr MG, Søreide JA. Pyloroplasty for benign gastric outlet obstruction — Indications and techniques. Scand J Surg. 2006;95:11–6. doi: 10.1177/145749690609500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dank JP, Kim S, Parisi MA, Brown T, Smith LT, Waldhausen J, et al. Outcome after surgical repair of junctional epidermolysis bullosa-pyloric atresia syndrome: A report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1243–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.10.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvestrini C, Heuschel RB, Thomson MA, Murch SH. Desquamative enterocolitis a cause of severe persistent diarrhea related to epidermolysis bullosa — Pyloric atresia syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:S274–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prabhu V, Sankar J, Srinivasan A, Sathiyasekaran M. Desquamative enterocolitis: An intestinal variant of Carmi syndrome presenting as protein-losing enteropathy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008;27:215–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellerio JE, Pulkkinen L, McMillan JR, Lake BD, Horn HM, Tidman MJ, et al. Pyloric atresia-junctional epidermolysis bullosa syndrome: Mutations in the integrin beta4 gene (ITGB4) in two unrelated patients with mild disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:862–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saurat JH, La chapelle JM, Lipsker D, Thomas L. 5th ed. Paris: Masson; 2009. Dermatologie et Infections Sexuellement Transmissibles. [Google Scholar]