Abstract

Gastroschisis is a congenital anomaly characterised by a defect in the anterior abdominal wall through which the intestinal contents freely protrude. Defect is located almost always to right of umbilicus. To our knowledge very few cases of left-sided gastroschisis have occurred and presented in literature. We report case of left-sided gastroschisis with caecal agenesis, short gut, and malrotation of intestine.

Keywords: Caecal agenesis, gastroschisis, malrotation

INTRODUCTION

The abdominal wall defect is located at junction of umbilicus and normal skin and almost always to the right of umbilicus, at the site of obliterated right umbilical vein.[1,2] Associated anomalies are rare but intestinal atresia is present in up to 15% of cases. Very few cases of left-sided gastroschisis are presented in the literature. Most of them were associated with extra intestinal anomalies.[3] We report a case of left-sided gastroschisis with caecal agenesis, short gut and malrotation of the intestine.

CASE REPORT

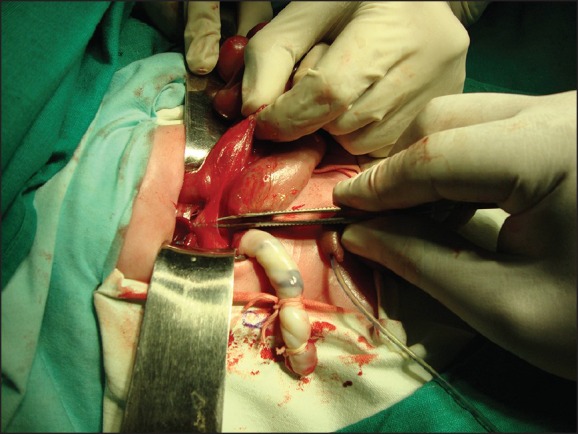

A 24 h old male baby, the product of spontaneous vaginal delivery weighing 2.4 kg, delivered to 22 years old primipara presented to the emergency room with evisceration of intestine from abdomen. Prenatally she was not diagnosed with gastroschisis. On examination, baby was hypothermic having tachypnoea. Defect was about 2 cm × 0.5 cm in size on the left side of umbilicus with evisceration of intestine. The eviscerated bowel was oedematous and dusky in colour [Figure 1]. There were no other associated anomalies seen preoperatively. Abdominal ultra sonography showed no renal or another anomaly. Chest X-ray showed no pulmonary hypoplasia.

Figure 1.

Eviscerated bowel

Patient was stabilised by putting him in warmer, oxygen supply and adequate intravenous fluids. After stabilisation patient was shifted to the operation theatre. Incision was extended vertically on either side for 2 cm. Intraoperative findings showed absence of caecum, appendix. Large bowel was short in length with no distinction of small and large bowel junction; small intestine was malrotated with ladds bands present [Figure 2]. Total length of bowel was about 30 cm. There was no situs inversus.

Figure 2.

Intestinal malrotation with ladds band

Mechanical stretching of anterior abdominal wall was done. As the bowel was short, it was reduced with minimal tension. Ladds procedure was done. All bands were removed, and malrotation was corrected. Primary closure of the defect was done with minimal tension [Figure 3]. Postoperative patient was put on a ventilator and total parenteral nutrition started. Patient expired after 1 day due to septicaemia, and clinical autopsy was done.

Figure 3.

Primary closure of the defect

DISCUSSION

Gastroschisis refers to an abdominal wall defect through which midgut and rarely other abdominal organs eviscerate.[4,5] Other viscera that may eviscerate is stomach, duodenum, bladder, liver and gonads.[4,5] In our case midgut along with stomach has eviscerated.

Gastroschisis should be differentiated from omphalocele that refers to defect of the abdominal wall in which the bowel and solid viscera are covered with peritoneum and amniotic membrane.[2,6,7] Defect in gastroschisis is usually smaller less than 4 cm compared to omphalocele.[2,6] Unlike in infants born with an omphalocele, in infants with gastroschisis the associated anomalies consist mostly of intestinal atresia.

Review of literature suggests that the incidence of extra intestinal congenital anomalies is significantly higher in left-sided gastroschisis as compared to right sided gastroschisis.[3] Reported extra intestinal anomalies include choledochal cyst, cleft lip, cleft palate, pulmonary hypoplasia, atrial septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus, etc.[1,5] However in our case no extra intestinal anomalies were detected. Intestinal anomalies included malrotation, caecal and appendicular agenesis and micro colon.

Actual molecular mechanism underlying gastroschisis remains unclear.[8] Most common theory put forward for right-sided gastroschisis is resorption of right umbilical vein at 4th week of gestation.[2] But the existence of left-sided gastroschisis points toward some other aetiology. Proposed theories include regression of left-sided omphalo mesenteric artery, failure of mesodermalisation of anterior abdominal wall with absence of abdominal components.[9] So every case of gastroschisis should undergo further evaluation to determine the cause of disease.

Outcomes in any case of gastroschisis are determined by many factors such as exteriorised bowel and associated congenital anomalies. Mortality in developed is less than 8%. This is supported by improvement in surgical care, improvement in neonatal intensive care, neonatal support and better nutritional services.

In our case, baby was delivered outside and presented to us late. Baby was already in shock and sepsis at the time of presentation. Although intestine was reduced into abdominal cavity baby died of septicaemia. This indicates the importance of early antenatal diagnosis, timely referral and better transport facility.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None Conflict of Interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yoshioka H, Aoyama K, Iwamura Y, Muguruma T. Two cases of left-sided gastroschisis: Review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:472–3. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1181-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.deVries PA. The pathogenesis of gastroschisis and omphalocele. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:245–51. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(80)80130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suver D, Lee SL, Shekherdimian S, Kim SS. Left-sided gastroschisis: Higher incidence of extraintestinal congenital anomalies. Am J Surg. 2008;195:663–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirza B, Ijaz L, Sheikh A. Evisceration and necrosis of gall bladder and evisceration of urinary bladder in a patient of gastroschisis. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7:43–4. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.59363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serber J, Stranzinger E, Geiger JD, Teitelbaum DH. Association of gastroschisis and choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:e23–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledbetter DJ. Gastroschisis and omphalocele. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:249–60, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arroyo Carrera I, Pitarch V, García MJ, Barrio AR, Martínez-Frías ML. Unusual congenital abdominal wall defect and review. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;119A:211–3. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw A. The myth of gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg. 1975;10:235–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(75)90285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoyme HE, Higginbottom MC, Jones KL. The vascular pathogenesis of gastroschisis: Intrauterine interruption of the omphalomesenteric artery. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;98:228–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]