Abstract

Mechanical signals play an integral role in bone homeostasis. These signals are observed at the interface of bone and teeth, where osteoblast-like periodontal ligament (PDL) cells constantly take part in bone formation and resorption in response to applied mechanical forces. Earlier, we reported that signals generated by tensile strain of low magnitude (TENS-L) are antiinflammatory, whereas tensile strain of high magnitude (TENS-H) is proinflammatory and catabolic. In this study, we examined the mechanisms of intracellular actions of the antiinflammatory and proinflammatory signals generated by TENS of various magnitudes. We show that both low and high magnitudes of mechanical strain exploit nuclear factor (NF)-κB as a common pathway for transcriptional inhibition/activation of proinflammatory genes and catabolic processes. TENS-L is a potent inhibitor of interleukin (IL)-1β-induced I-κBβ degradation and prevents dissociation of NF-κB from cytoplasmic complexes and thus its nuclear translocation. This leads to sustained suppression of IL-1β-induced NF-κB transcriptional regulation of proinflammatory genes. In contrast, TENS-H is a proinflammatory signal that induces I-κBβ degradation, nuclear translocation of NF-κB, and transcriptional activation of proinflammatory genes. These findings are the first to describe the largely unknown intracellular mechanism of action of applied tensile forces in osteoblast-like cells and have critical implications in bone remodeling.

Keywords: NF-κB, signal transduction, osteoblastic cells, mechanical strain

The periodontal ligament (PDL), located at the interface of bone and teeth, is a mechanosensitive tissue that responds to compressive and tensile forces disparately (1-6). This phenomenon is observed when applied mechanical forces result in bone resorption at sites of compression and deposition at sites experiencing tension. PDL cells with an osteoblast-like phenotype synthesize bone, have the necessary signaling and effector mechanisms to both sense applied mechanical forces and mount a stream of cellular responses such as differentiation, matrix catabolism, and matrix synthesis (6-11).

The precise mechanisms responsible for conversion of mechanical signals into biochemical responses that influence signal transduction pathways and ultimately bone remodeling still remain unclear. In response to mechanical loading, PDL cells at sites opposing compressive forces are exposed to tensile forces. At sites experiencing tension, the magnitude of tensile strain appears to be critical in regulating the ultimate responses of PDL cells (7, 9-14). Tensile force distribution in the PDL in vivo and in vitro leads to inflammation and synthesis of mediators associated with tissue destruction, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2) (9-15). These mediators augment matrix degradation and inhibit the synthesis of matrix-associated proteins. However, lower physiologic levels of tensile forces induce anabolic or synthetic responses. We and others have examined how the intracellular signals generated by low magnitudes of tensile strain counteract the effects of inflammatory mediators to inhibit catabolic events (6, 7, 16-19) and allow augmentation of anabolic events. In addition, we are interested in how intracellular signals generated by excessive levels of tensile strain manifest proinflammatory responses.

The signals induced by proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α, are transmitted to the nucleus through activation of a series of kinases that lead to phosphorylation, ubiquination, and ultimate degradation of I-κB, a protein that sequesters nuclear factor (NF)-κB in the cytoplasm (20, 21). NF-κB is a multifunctional transcription factor associated with proinflammatory responses. Upon release from I-κB, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to consensus sequences of several proinflammatory genes to initiate mRNA transcription (21). Because tensile strain inhibits as well as augments inflammation, we speculated that both anti- and proinflammatory actions of TENS may be mediated by a common signal transduction pathway, involving modulation of NF-κB activation. In this report, we show that signals generated by tensile strain act on osteoblast-like PDL cells in a magnitude-dependent manner. Furthermore, the antiinflammatory effects of tensile strain of low magnitude (TENS-L) and proinflammatory effects of tensile strain of high magnitude (TENS-H) are both regulated via NF-κB transcription factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and materials

Human PDL cells were isolated, cloned, and cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% defined fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, following University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approval (22). PDL cell clones, designated as PL-150 and PL-75 (from white females, both 18 years of age) and PL-484 (from a white male, age 22 years), retained their osteoblast-like phenotype between 6th and 12th passages as shown by the presence of alkaline phosphatase, the formation of calcium phosphate nodules, expression of mRNA for TGF-β1 and osteocalcin, and parathyroid hormone-induced cAMP formation, as described previously (22). No significant differences in alkaline phosphatase activity and calcium phosphate nodule formation were observed between these passages (6, 22).

Application of equibiaxial strain on PDL cells in vitro

To mimic the effects of mechanical forces at tension sites in vitro, PDL cells (5×105/well) were grown on collagen type I-coated Bioflex II, six-well culture plates to 80% confluence (7–8 days). Subsequently, cells were washed and incubated in tissue culture medium (TCM) without FCS but supplemented with serum replacement supplements (SRM 1; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) overnight. The cells were subjected to equibiaxial TENS in a Flexercell Strain Unit (Flexcell International, Hillsborough, NC) (6, 11, 12, 17, 23) at a rate of 0.005 Hz. The plates were placed on a loading station (located in a 5% CO2 incubator with 95% humidity), so that a vacuum deformed the membrane across the post-face to create uniform biaxial strain (Fig. 2A and 2B). The strain was calculated as circumferential strain = 2π (change in radius)/2π (original radius) = (change in radius)/(original radius) = radial strain. The results showed a linear relationship between vacuum level and strain. In all experiments, PDL cells grown on Bioflex II plates were assigned to four different treatment regimens: (a) untreated controls, (b) treated with rhIL-1β alone (1 ng/ml, or as stated), (c) treated with TENS alone (magnitude as specified), or (d) rhIL-1β and TENS.

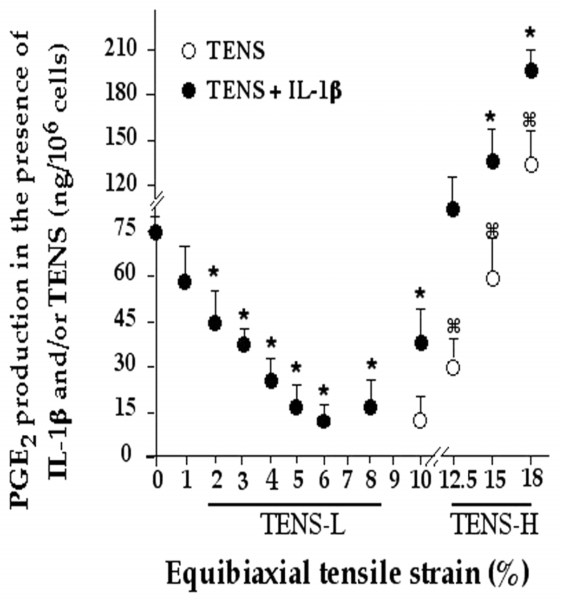

Figure 2. Signals generated by tensile strain of low magnitude (TENS-L) suppress IL–1β–induced COX-2 mRNA expression and synthesis.

Human periodontal ligament cells were exposed to 3%, 6%, or 8% TENS in the presence or absence of IL-1β (1 ng/ml). COX-2 mRNA expression by RT-PCR (A) and COX-2 synthesis by Western blot analysis (B) were measured after 4 and 24 h, respectively. Data represent relative intensity of each band by semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data represent one out of three separate experiments. B) Points represent mean and SE of triplicate values. *P≤0.05 compared with cells treated with IL-1β alone.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was extracted with the use of an RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Santa Clara, CA), according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocols. A total of 0.5 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed with 1 μg oligo dT (12–18 oligomer; Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT) and 200 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase for 60 min at 37°C. The cDNA, thus obtained, was amplified by 0.1 μg of primers in a reaction mixture containing 200 μM dNTP, 0.1 U of Taq polymerase in PCR buffer (Perkin Elmer). PCR was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer) for 30 cycles of 40 s at 94°C, 40 s at 62°C, and 60 s at 72°C. The sequence of sense and antisense primers was as follows: GAPDH (548 bp), sense 5′-GGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGG-3′ and antisense 5′-GTCATGAGTCCTTCCACGAT-3′; cyclooxygenase-2 (COX 2), sense 5′-TTCAAATGAGATTGTGGGAAAATTGCT-3′ and antisense 5′AGATCATCTCTGCCTGA GTATCTT-3′.

NF-κB activation

Nuclear translocation of NF-κB was determined by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as described previously (24). In brief, nuclear extracts were prepared from cells (2×106) treated with various regimens and incubated for 15 min at 37°C with 32P-labeled 45-mer double-stranded NF-κB oligonucleotide and 4 μg protein with 16 fmoles of DNA from HIV long terminal repeat, 5′ TTGTTACAAGGGACTTTCCGCTGGGGACTTTCCAGGGAGGCGTGG-3′ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The DNA protein complexes were separated from free nucleotide on 6% native polyacrylamide gels. The specificity of binding was determined by competition with unlabeled nucleotide. For supershift EMSAs, nuclear extracts were incubated with preimmune serum or antibodies (Abs) against p50, p65, p52, c-Rel p75, or Rel B p68 of NF-κB for 30 min at room temperature before analyzing the complexes by EMSA. The NF-κB binding to its consensus sequences was visualized in dried gels, and the bands were quantitatively analyzed by scintillation counting. In some experiments, we analyzed the nuclear translocation of NF-κB by immunofluorescence, using rabbit antiNF-κB p65 IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and CY3 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). The images were digitally recorded with an epifluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate filters. In some experiments, in order to inhibit nuclear translocation of NF-κB, we incubated cells with various concentrations of caffeic acid phenylethylester (CAPE) for 10 min and then subjected them to TENS as described previously.

Degradation of I-κB

To determine the levels of I-κB, we prepared postnuclear extracts from cells subjected to regimens described previously and resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)/10% polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis, the proteins were electrotransferred to Immunolon membranes (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA), probed with rabbit anti-I-κBα or anti-I-κBβ IgG, and detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). In some experiments, I-κB was examined in the cells by immunofluorescence, using rabbit anti-I-κBα or anti-I-κBβ antibodies and CY3 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG as a detection agent.

RESULTS

TENS exerts antiinflammatory and proinflammatory effects in a magnitude-dependent manner

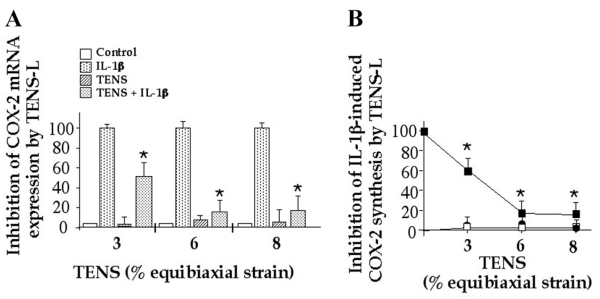

IL-1β induces PGE2 production and initiates alveolar bone degradation through activation of multiple proinflammatory genes (5, 6, 17), including COX-2. Therefore, we used rhIL-1β-dependent PGE2 production as an indicator to evaluate the effects of TENS on the IL-1β signal transduction pathway. Figure 1 summarizes the effects of various magnitudes of TENS on IL-1β-induced PGE2 production. Consistent with the normal cell conditions, minimal PGE2 production was observed in the culture supernatants of control cells. Treatment of cells with IL-1β resulted in a significant increase in the synthesis of PGE2. However, coexposure of PDL cells with IL-1β and TENS-L (2–8%) resulted in a significant inhibition (P≤0.05) of IL-1β-induced PGE2 production. PGE2 production was unaffected by TENS-L alone. In contrast, TENS-H (12.5% or higher) were proinflammatory and induced marked up-regulation of PGE2. In addition, simultaneous exposure of cells to IL-1 and TENS-H resulted in PGE2 production that was greater than that observed with rhIL-1β alone (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Effect of various magnitudes of tensile strain (TENS) on prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2) production in the presence or absence of IL-1β in periodontal ligament cells.

Cells were exposed to various magnitudes of TENS in the presence (●) or absence (○) of submaximal concentrations of IL-1β (0.4 ng/ml) for 24 h, and the PGE2 accumulation in the culture supernatants was measured by radioimmunoassays. Cells exposed to an 8% or lower magnitude of TENS alone did not exhibit PGE2 production. IL-1β alone augmented a distinct increase in PGE2 production, which was markedly inhibited by 2–8% TENS. Cells exposed to a 10% or higher magnitude of TENS exhibited a dose-dependent up-regulation of PGE2 production and exhibited additive effects in the presence of IL-1β. All points represent mean and SE of the mean of triplicate values. *P≤0.05 compared with cells treated with IL-1β alone, and ⌘P≤0.05 compared with untreated controls. (TENS-L, tensile strain of low magnitude; TENS-H, tensile strain of high magnitude.)

TENS-L inhibits IL-1β-dependent PGE2 production upstream of COX-2 mRNA induction

Because TENS-L abrogated rhIL-1β-induced PGE2 production, we measured COX-2 mRNA expression in the presence and absence of TENS to determine whether its effects are perceived at the transcriptional level. Semiquantitative assessment of PCR products revealed that TENS-L (3%, 6%, and 8%) significantly suppressed rhIL-1β-induced COX-2 mRNA (53%, 86%, and 82%) within the initial 4 h (Fig. 2A). This was paralleled by a marked decrease in COX-2 synthesis (Fig. 2B). PDL cells subjected to TENS alone or to untreated control cells exhibited minimal COX-2 mRNA expression and synthesis. These observations suggest that TENS-L acts upstream of mRNA transcription in the rhIL-1β signal transduction cascade.

TENS-H induces COX-2 mRNA induction

To determine the intracellular target sites of action, we measured the effects of TENS-H on COX-2 mRNA expression. As shown in Figure 3A and 3B, TENS-H (15%) alone up-regulated sustained COX-2 mRNA synthesis between 4 and 48 h. Combined treatment of PDL cells with TENS-H and submaximal concentrations of rhIL-1β (0.4 ng/ml) revealed additive effects, that is, total COX-2 mRNA production in cells exposed to rhIL-1β and TENS-H was greater than that expressed by cells treated individually with rhIL-1β or TENS. Correspondingly, this increase in COX-2 mRNA expression was reflected in the PGE2 production after 12, 24, and 48 h (Fig. 3C). These observations demonstrate that the intracellular target sites of TENS-H are also upstream of COX-2 mRNA induction and may involve proinflammatory pathways similar to those of rhIL-1β.

Figure 3. Signals generated by tensile strain of high magnitude (TENS-H) induce COX-2 mRNA and prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2) production.

Periodontal ligament cells were exposed to 15% TENS in the absence or presence of IL-1β (1 ng/ml) for 4, 24, or 48 h. Subsequently, RNA was extracted from cells and analyzed for COX-2 mRNA expression by RT-PCR (A), and the bands were semiquantitatively analyzed by densitometric analysis (B). C) PGE2 (ng/106 cells) accumulation in culture supernatants of cells exposed to TENS-H alone, IL-1β (1 ng/ml), IL-1β (0.4 ng/ml), or TENS-H and IL-1β (0.4 ng/ml) over a period of 24 h as analyzed by radioimmunoassays. A) Data represent one out of three separate experiments. B and C) Data represent mean and SE of triplicate values in one out of three separate experiments. *P≤0.05 compared with cells treated with IL-1β alone and ✠P≤0.05 compared with untreated cells.

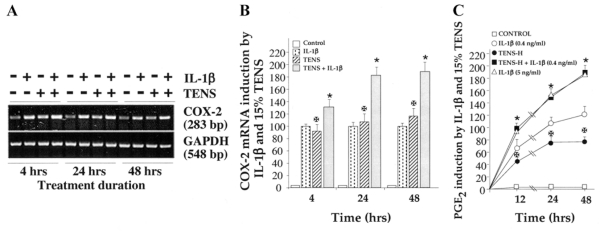

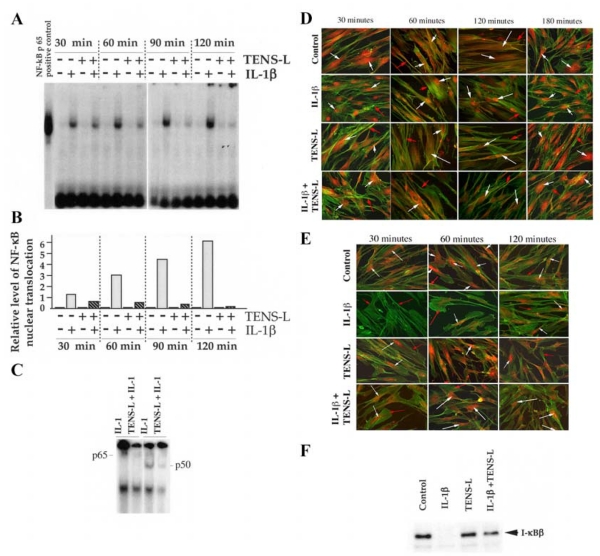

TENS-L inhibits IL-1β-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB

To investigate the intracellular mechanisms by which TENS-L may attenuate IL-1β-induced proinflammatory responses, we evaluated the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, the major transcription factor involved in the signal transduction of proinflammatory cytokines. PDL cells were exposed to TENS-L, and the NF-κB nuclear translocation was assessed by EMSA. No significant differences in NF-κB nuclear translocation in control cells and cells treated with TENS-L alone were observed. Cells treated with IL-1β showed rapid translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus. However, treatment of cells with TENS-L and IL-1β resulted in a 56%, 82%, 93%, and 94% suppression of NF-κB transactivation within 30, 60, 90, and 120 min of activation, respectively (Fig. 4A and 4B). IL-1β-dependent activation of proinflammatory genes involves nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 and p50 heterodimers. Because the subunit structures play a critical role in the modulation of immune responses, we next determined the subunit structure of NF-κB involved in TENS-L actions. The supershift EMSA revealed that IL-1β induces transactivation of NF-κB heterodimers comprised of p65 and p50 subunits, and TENS-L directly inhibits their translocation (Fig. 4C). Supershift EMSA revealed that TENS-L does not induce nuclear translocation of Rel B (p68), p52, or c-Rel (data not shown).

Figure 4. Tensile strain at low magnitude (TENS-L) inhibits rhIL-1β-induced nuclear translocation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB.

A) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis of nuclear extracts of untreated cells or cells treated with IL-1β (1 ng/ml), TENS-L (6%), or TENS-L (6%) and IL-1β for 30, 60, 90, or 180 min, showing inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation by TENS-L. B) Quantitative analysis of 32P associated with each band shown in A. C) Analysis of subunits of NF-κB involved in TENS-L actions by supershift EMSA, using antibodies to p65 (Rel A) and p50 subunits of NF-κB. D) Nuclear translocation of NF-κB as assessed by immunofluroscence. NF-κB was stained with anti-NF-κB p65 primary IgG and TRITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG as second antibodies (white arrows). Cellular β-actin is shown by FITC-conjugated phalloidin (red arrows). The panels show that in untreated control cells, NF-κB is cytoplasmic at all time points. In cells treated with rhIL-1β (1 ng/ml) for 30, 60, 120, or 180 min, NF-κB completely translocated to the nucleus, with some cytoplasmic NF-κB at 60, 120, and 180 min. In cells treated with TENS alone, NF-κB was localized in the cytoplasm. In cells treated with TENS and rhIL-1β for 30, 60, 120, and 180 min, TENS-L (6%) markedly abrogated IL-1β-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB at all time points as evidenced by its presence in the cytoplasm. E) Inhibition of IL-1β-induced I-κBβ degradation by TENS-L (6%) by immunofluorescence analysis. Panels show the presence of cytoplasmic I-κBβ in untreated control cells and cells treated with TENS-L (6%) alone (white arrows) over a period of 30–120 min. Cells treated with IL-1β exhibit near complete absence of I-κBβ due to its degradation within the first 30 min and its resynthesis at 60 and 120 min. Cells treated with TENS-L and IL-1β show the suppression of IL-1β-induced I-κBβ degradation by TENS-L as evidenced by the presence of I-κBβ in the cytoplasm at all time points tested. Cellular actin was stained by phalloidin-FITC to reveal the cell morphology (red arrows).

F) Western blot analysis demonstrating inhibition of I-κBβ degradation by TENS-L (6%). The cytoplasmic extracts of PDL cells treated with TENS-L in the presence or absence of IL-1β for 30 min, were probed with rabbit anti-I-κBβ for Western blot analysis. Data represent one of three separate experiments.

To verify that TENS-L inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation was by cytoplasmic retention and not degradation, the presence of NF-κB was detected by immunofluorescence with the use of anti-NF-κB antibodies. In IL-1β-activated PDL cells, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus within the first 30 min and is resynthesized and retransported to the cytoplasm during the next 180 min (Fig. 4D). However, cotreatment of cells with 6% TENS and IL-1β resulted in the retention of NF-κB in the cytoplasm throughout 180 min incubation. These observations suggest that TENS-L did not stimulate degradation but inhibited nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Similar to untreated control cells, treatment of cells with 6% TENS alone did not exhibit nuclear translocation of NF-κB.

Degradation of I-κBβ by a phosphorylation-dependent and ubiquination-dependent pathway represents an important event for the unmasking of NF-κB translocation sequences and the initiation of transcription by the nuclear factor (20). To gain further insight into the role of TENS-L in the inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation, we determined the effects of TENS-L on IL-1β-induced I-κBβ degradation. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that in cells exposed to IL-1β, I-κBβ content was rapidly degraded within 30 min but was replenished after 60 min (Fig. 4E). In contrast, 6% TENS-L markedly inhibited IL-1β-induced I-κBβ degradation within the first 30 min, which was sustained over the next 120 min. The levels of cytoplasmic I-κBβ in control cells and cells treated with TENS-L alone remained unchanged.

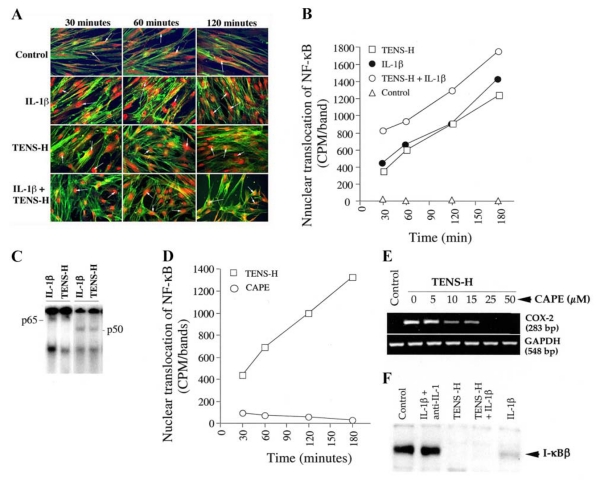

TENS-H induces nuclear translocation of NF-κB

To investigate whether the proinflammatory actions of TENS-H and antiinflammatory actions of TENS-L utilize a common pathway, we examined transactivation of NF-κB by TENS-H (15%). NF-κB nuclear translocation by immunofluorescence revealed that TENS-H induces rapid nuclear translocation of NF-κB, similar to IL-β-treated cells. This effect of TENS-H was sustained for 180 min (Fig. 5A). The kinetics of nuclear translocation of NF-κB by submaximal concentrations of IL-1β (0.4 ng/ml) revealed an increase in NF-κB accumulation in the nucleus over a period of 30–180 min. Similarly, TENS-H also induced a time-dependent increase in the nuclear translocation of NF-κB. However, simultaneous treatment of cells with TENS-H and IL-1β (0.4 ng/ml) showed that the effects of TENS and IL-1β were additive (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, similar to IL-1β, the heterodimers of NF-κB translocated to the nucleus in response to TENS-H were also composed of p65 and p50 subunits (Fig. 5C). TENS-H does not induce nuclear translocation of Rel B (p68), p52, or c-Rel, as revealed by supershift EMSA (data not shown).

Figure 5. Signals generated by tensile strain at high magnitude (TENS-H) initiate proinflammatory gene induction via nuclear translocation of NF-κB.

A) Cells were either untreated or treated with TENS-H (15%) in the presence or absence of IL-1β (1 ng/ml) and subjected to immunofluorescence staining as described in Figure 4D. Panels show the presence of NF-κB in the cytoplasms in untreated control cells (white arrows). Exposure of periodontal ligament (PDL) cells to 15% TENS-H, IL-1β, or TENS-H and IL-1β for 30–120 min resulted in rapid and sustained nuclear translocation of the majority of NF-κB as evidenced by red stained nuclei (white arrows). Actin was stained with FITC Phalloidin to show the morphology of PDL cells. B) Quantitative assessment of bands obtained by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis of nuclear extracts of untreated cells or cells treated with IL-1β (0.4 ng/ml), TENS-H (15%), or TENS-H and IL-1β for 30, 60, 90, or 180 min, demonstrating NF-κB nuclear translocation by TENS-H and IL-1β and the additive effects of TENS-H and IL-1β. C) Subunit structure of NF-κB translocated to the nucleus following exposure of cells to TENS-H by supershift EMSA, using antibodies to p65 (Rel A) and p50 subunits of NF-κB. D) Inhibition of TENS-H-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB by caffeic acid phenylethylester (CAPE). PDL cells were either untreated or treated with CAPE (25 μM) for 10 min and then exposed to TENS (15%) for 30, 60, 120, or 180 min. The inhibition of TENS-H-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB by CAPE was analyzed by quantitative assessment of each band in gels following EMSA analysis. E) Inhibition of TENS-H-induced COX-2 mRNA expression in cells exposed to CAPE. PDL cells were exposed to various concentrations of CAPE (0, 5, 10, 15, 25, or 50 μM) for 10 min and subsequently exposed to TENS-H for 4 h. RT-PCR analysis showing that TENS-H induced COX-2 mRNA expression was completely abrogated by 25 μM CAPE. F) TENS-H (15%) induced degradation of I-κBβ in PDL cells. Western blot analysis showing the presence of I-κBβ in the cytoplasmic fraction of untreated control cells and cells treated with neutralized IL-1β (1 ng/ml + 2 μg of rabbit anti-IL-1β IgG), whereas 30-min exposure of cells to TENS-H, IL-1β (1 ng/ml), or TENS-H and IL-1β resulted in a rapid degradation of I-κBβ.

To confirm the involvement of NF-κB in TENS-H-induced NF-κB activation, we used a cell-permeable inhibitor of NF-κB, CAPE. Treatment of cells with CAPE (25 μM) dramatically affected the ability of NF-kB to translocate to the nucleus at all time points tested (Fig. 5D). In addition, CAPE inhibited the ability to drive transcription of NF-kB-dependent COX-2 mRNA, between the concentrations of 5 and 25 μM (Fig. 5E). This suggests that NF-kB serves as a transcription factor for proinflammatory gene induction by TENS-H.

To establish mechanisms of NF-κB nuclear translocation by TENS-H, we next determined whether TENS-H stimulated I-κBα degradation. Western blot analysis revealed that TENS-H induces rapid degradation of I-κBβ within 30 min, similar to that observed in the presence of IL-1β alone (Fig. 5F).

DISCUSSION

The results presented here describe novel intracellular mechanisms by which the actions of TENS-L and TENS-H are regulated. The most striking finding in this work is that the magnitude of TENS is a critical determinant in regulating the ultimate responses of osteoblast-like PDL cells. Essentially, TENS-L (2–8%) is not perceived as an inflammatory signal and does not affect COX-2 induction or PGE2 synthesis. However, it directly abrogates inflammatory insults dose dependently by inhibiting IL-1β-induced COX-2 mRNA expression and PGE2 production. TENS-L also inhibits transcription of several other proinflammatory genes such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9 in PDL cells (6, 17). Collectively, these findings provide evidence that signals generated by TENS-L inhibit the signal transduction pathway of IL-1β upstream of mRNA induction.

In contrast, TENS-H (12.5–18%) induces transcriptional activation of proinflammatory genes as evidenced by COX-2 mRNA expression and PGE2 synthesis. The actions of TENS-H also markedly up-regulate IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, β-integrins, and plasminogen activator, all of which take part in activation of the immune system and/or induce matrix degradation (6, 17, 23, 25-27). This suggests that signals generated by TENS-H itself are proinflammatory. Furthermore, TENS-H and IL-1β together exert additive effects to up-regulate proinflammatory responses.

NF-κB transcription factors have an established role in cytosolic signaling of proinflammatory cytokines through their nuclear translocation and subsequent activation of a plethora of genes. Our study shows that the NF-κB signal transduction pathway is central to the proinflammatory and the antiinflammatory actions of TENS. The antiinflammatory effects of TENS-L are mediated by sustained abrogation of IL-1β-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB. NF-κB/Rel proteins exist as homo- or heterodimers. Although most of the NF-kB dimers are activators of transcription, the p50/50 and p52/52 homodimers can repress the transcription of their target genes (20, 21). Therefore, we examined whether TENS-L mediates its antiinflammatory actions via activation of distinct subunit structures of the NF-κB. Because TENS-L did not induce nuclear translocation of c-Rel, p52, or Rel B, it appears to suppress IL-1β responses by inhibiting nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 heterodimers. These findings suggest that TENS-L specifically represses intracellular signals generated by IL-1β.

We also show that TENS-L supresses the dissociation of NF-κB from cytosolic complexes with I-κBβ and thus prevents its entry into the nucleus. Because TENS-L does not down-regulate IL-1β receptors (17), the molecular targets of anticatabolic/antiinflammatory signals of TENS-L may lie between IL-1 receptor complex and I-κBβ degradation. It remains unclear what types of mechanosensors perceive signals generated by TENS-L in PDL cells. In chondrocytes, α5β1 integrins serve as mechanosensors (28). It is intriguing that TENS-L directly inhibits the NF-κB pathway for its antiinflammatory actions, because antiinflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 use JAK-STAT pathways to inhibit proinflammatory signals (29, 30).

TENS-H is a potent proinflammatory signal, thus it is not surprising that its actions are mediated by NF-κB transactivation (11, 20, 21). In line with our observations that TENS-H actions are mediated by NF-κB transactivation is the finding that CAPE, a cell-permeable inhibitor of NF-κB, completely abrogates the TENS-H-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation and ultimately COX-2 mRNA expression. Furthermore, the findings that TENS-H induces I-κBβ degradation and nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 heterodimers of NF-kB also suggest that TENS-H induces proinflammatory signals. Thus, despite being a physical signal, TENS-H acts in a manner similar to molecular activators that stimulate transcriptional activity of NF-κB. Interestingly, in our studies, TENS-H induced a sustained nuclear translocation of NF-κB that was detectable in the nucleus for 3 h. This is similar to endothelial cells, in which NF-κB transmigration is sustained during the initial 4 h in response to mechanical stretch (31). However, in fibroblasts, in response to mechanical stretch, NF-κB levels can be detected within 2 min and peak at 4 min (15). Thus, the time dependence of NF-κB activation by mechanical strain appears to depend on the cell type.

Taken together, we provide evidence for the first time that the NF-κB pathway is central to TENS actions. Low levels of TENS-L generate signals that inhibit NF-κB transactivation to limit inflammation triggered by IL-1β. In contrast, TENS-H generates signals that use NF-κB to initiate proinflammatory gene transcription to induce soft and hard tissue destruction. Interestingly, TENS-L also induces anabolic signals, that is, synthesis of matrix-associated proteins (i.e., collagen type-I, osteocalcin, and alkaline phosphatase) in the presence of IL-1β (6, 7, 17, 18). Whether these anabolic actions of TENS-L are a consequence of inhibition of NF-κB-activated catabolic gene induction or are mediated via distinct anabolic pathways is not clear. TENS-H inhibits anabolic gene induction (1, 9, 11, 12). Whether these catabolic actions of TENS-H involve inhibition of signal transduction pathways other than NF-κB has yet to be examined.

REFERENCE

- 1.Fermor B, Gundle R, Evans M, Emerton M, Pocock A, Murray D. Primary human osteoblast proliferation and prostaglandin E2 release in response to mechanical strain in vitro. Bone. 1998;22:637–643. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toma CD, Ashkar S, Gray ML, Schaffer JL, Gerstenfeld LC. Signal transduction of mechanical stimuli is dependent on microfilament integrity: identification of osteopontin as a mechanically induced gene in osteoblasts. J. Bone Min. Res. 1997;12:1626–1636. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.10.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikegame M, Ishibashi O, Yoshizawa T, Shimomura J, Komori T, Ozawa H, Kawashima H. Tensile stress induces bone morphogenetic protein 4 in preosteoblastic and fibroblastic cells, which later differentiate into osteoblasts leading to osteogenesis in the mouse calvariae in organ culture. J. Bone Min. Res. 2001;16:24–32. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein-Nulend J, Sterck JG, Semeins CM, Lips P, Joldersma M, Baart JA, Burger EH. Donor age and mechanosensitivity of human bone cells. Osteoporos. Int. 2002;13:137–146. doi: 10.1007/s001980200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCulloch CA, Lekic P, McKee MD. Role of physical forces in regulating the form and function of the periodontal ligament. Periodontol. 2000;2000;24:56–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2240104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long P, Buckley MJ, Liu F, Kapur R, Agarwal S. Signalling by mechanical strain involves transcriptional regulation of proinflammatory genes in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells in vitro. Bone. 2002;30:547–552. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard PS, Kucich U, Taliwal R, Korostoff JM. Mechanical forces alter extracellular matrix synthesis by human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. J. Periodont. Res. 1998;33:500–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko KS, McCulloch CA. Intercellular mechanotransduction: cellular circuits that coordinate tissue responses to mechanical loading. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;285:1077–1083. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiba M, Komatsu K. Mechanical responses of the periodontal ligament in the transverse section of the rat mandibular incisor at various velocities of loading in vitro. J. Biomech. 1993;26:561–570. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidovitch Z, Norton LA. Biological Mechanisms of Tooth Movement and Craniofacial Adaptation. In: Davidovitch Z, Norton L, editors. Biological Mechanisms of Tooth Movement and Craniofacial Adaptation. Harvard Soc. Adv. Orthodontics; Boston: 1996. pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu N, Ozawa Y, Yamaguchi M, Goseki T, Ohzeki K, Abiko Y. Induction of COX-2 expression by mechanical tension force in human periodontal ligament cells. J. Periodontol. 1998;69:670–677. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.6.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein-Neulend J, Van der Plas A, Semeins CM, Ajubi NE, Frangos JA, Burger EH. Sensitivity of osteocytes to biomechanical stress in vitro. FASEB J. 1995;9:441–445. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.5.7896017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chien HH, Lin WL, Cho MI. Interleukin-1beta-induced release of matrix proteins into culture media causes inhibition of mineralization of nodules formed by periodontal ligament cells in vitro. Cal. Tissue. Internat. 1999;64:402–413. doi: 10.1007/pl00005822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolcato-Bellemin AL, Elkaim R, Abehsera A, Fausser JL, Haikel Y. Expression of mRNAs encoding for alpha and beta integrin subunits, MMPs, and TIMPs in stretched human periodontal ligament and gingival fibroblasts. J. Dent. Res. 2000;79:1712–1716. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790091201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoh H, Ishiguro N, Sawazaki S, Amma H, Miyazu M, Iwata H, Sokabe M, Naruse K. Uni-axial cyclic stretch induces the activation of transcription factor nuclear factor kappaB in human fibroblast cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:405–407. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0354fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burger EH, Klein-Nulend J, Veldhuijzen JP. Mechanical stress and osteogenesis in vitro. J. Bone Min. Res. 1992;7:397S–401S. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650071406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long P, Hu J, Buckley M, Agarwal S. Low magnitude of Tensile Strain Inhibits IL 1β-dependent induction of inflammatory cytokines and induces synthesis of IL-10 in human PDL cells in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 2001;80:1416–1420. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800050601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin J, Murphy T, Nanes MS, Fan X. Mechanical strain inhibits expression of osteoclast differentiation factor by murine stromal cells. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C1126–C1132. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.6.C1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang JH, Briggs WH, Libby P, Lee RT. Small mechanical strains selectively suppress matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression by human vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6550–6555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109:S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal S, Chandra CS, Piesco NP, Langkamp HH, Bowen L, Baran C. Regulation of periodontal ligament cell functions by Interleukin-1β. Infect. Imm. 1998;66:932–937. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.932-937.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gassner R, Buckley MJ, Evans CH, Georgescu H, Studer R, Stefanovich-Racic M, Piesco NP, Agarwal S. Cyclic Tensile Stress exerts antiinflammatory actions on chondrocytes by inhibiting inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2187–2192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaturvedi MM, Kumar A, Darney BG, Agarwal S, Aggarwal BB. Sanguinarine is a potent inhibitor of NF-kB, IkBβ phosphorylation, and degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30129–30134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long P, Gassner R, Agarwal S. Tumor necrosis factor-a-dependent proinflammatory gene induction is inhibited by cyclic tensile strain in articular chondrocytes in vitro. Arth. Rheumat. 2001;44:2311–2319. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2311::aid-art393>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long P, Hu J, Piesco N, Buckley M, Agarwal S. Low magnitude of tensile strain inhibits IL-1beta-dependent induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and induces synthesis of IL-10 in human periodontal ligament cells in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 2001;80:1416–1420. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800050601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi M, Shimizu N, Ozawa Y, Saito K, Miura S, Takiguchi H, Iwasawa T, Abiko Y. Effect of tension-force on plasminogen activator activity from human periodontal ligament cells. J. Periodont. Res. 1997;32:308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salter DM, Millward-Sadler SJ, Nuki G, Wright MO. Integrin-interleukin-4 mechanotransduction pathways in human chondrocytes. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 2001;39:S49–S60. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200110001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donnelly RP, Dickensheets H, Finbloom DS. The interleukin-10 signal transduction pathway and regulation of gene expression in mononuclear phagocytes. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:563–573. doi: 10.1089/107999099313695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imada K, Leonard WJ. The Jak-STAT pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2000;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du W, Mills I, Sumpio BE. Cyclic strain causes heterogeneous induction of transcription factors, AP-1, CRE binding protein and NF-kB, in endothelial cells: species and vascular bed diversity. J. Biomech. 1995;28:1485–1491. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]