Abstract

Degradation of inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) into small molecular complexes is often observed in the physiological environment; however, how this process influences renal clearance of inorganic NPs is largely unknown. By systematically comparing renal clearance of degradable luminescent glutathione coated copper NPs (GS-CuNPs) and their dissociated products, Cu(II)-glutathione disulfide (GSSG) complexes (Cu(II)-GSSG), we found that GS-CuNPs were eliminated through the urinary system surprisingly faster and accumulated in the liver much less than their smaller dissociation counterparts. With assistance of radiochemistry and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, we found that the observed “nano size” effect in enhancing renal clearance is attributed to the fact that GS-CuNPs are more resistant to serum protein adsorption than Cu(II)-GSSG. In addition, since dissociation of GS-CuNPs follows zero-order chemical kinetics, their renal clearance and biodistribution also depend on initial injection doses and their dissociation processes. Quantitative understanding of size effect and other factors involved in renal clearance and biodistribution of degradable inorganic NPs will lay down a foundation for further development of renal-clearable inorganic NPs with minimized nanotoxicity.

INTRODUCTION

In order to minimize nonspecific accumulation of inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) in reticuloendothelial system (RES) organs (liver, spleen, etc.), significant efforts have been devoted to developing renal-clearable inorganic NPs.1–3 For instance, pioneering work done by Choi et al. on the renal-clearable quantum dots (QDs) showed that the zwitterionic cysteine coated QDs with a hydrodynamic diameter (HD) smaller than 5.5 nm can be rapidly cleared out through the urinary system within 4 h and less than ~5% of the QDs were found in the liver.1 The origin of such efficient renal clearance was due to the fact that zwitterionic ligands can behave like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) ligands to minimize serum protein adsorption while maintaining the HD of the QDs below kidney filtration threshold (KFT: ~5.5 nm).1 While zwitterionic cysteine can greatly enhance renal clearance of QDs, we found that ~3 nm cysteine coated gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were not renal-clearable because of their low physiological stability.4 Recently, we have developed zwitterionic glutathione (GSH) coated gold NPs (GS-AuNPs) with a HD of ~3 nm, which also exhibited desired renal clearance and low nonspecific RES accumulation: more than 50% injection dose (ID) of GS-AuNPs were cleared through the urine and only ~3%ID were accumulated in the liver 24 h post injection (p.i.).4 Not limited to those ultrasmall NPs, large nanosystems assembled from ultrasmall AuNPs can still be cleared out through the urinary system after dissociation, opening up a new path to design renal-clearable nanostructures with integrated functionality.5

While considerable understanding of renal clearance of inorganic NPs have been achieved in the past few years, these known renal-clearable NPs are generally chemically stable NPs and they seldom dissociate into even smaller molecular fragments such as metal complexes in the physiological environment during circulation.1,4 On the other hand, a large number of nanostructures created in the past decades often have some unique functionalities but might not be as stable as gold NPs or well-protected QDs.6,7 Therefore, a fundamental question is how those inorganic NPs that can break down into even smaller molecular complexes behave in vivo. In other words, do the smaller fragments always mean more efficient clearance? Herein, we used luminescent GSH coated CuNPs (GS-CuNPs) as a model to address this fundamental question because GS-CuNPs are known to dissociate into Cu(II)-glutathione disulfide (GSSG) complexes (Cu(II)-GSSG).6,8–11 Quantitative investigation of their in vitro stability and serum protein adsorption as well as in vivo behaviors show that GS-CuNPs were eliminated much faster through the urinary system, and accumulated in the liver much less than their smaller dissociation complexes. The observed unique “nano size” effect in enhancing renal clearance is fundamentally because GS-CuNPs have higher resistance to serum protein adsorption than Cu(II)-GSSG complexes even though their sizes are larger. This quantitative understanding and control of in vivo behaviors of these chemically instable NPs is fundamentally important for further expansion of our library of renal-clearable NPs and opening up a new path for designing more diverse clinically translatable inorganic NPs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

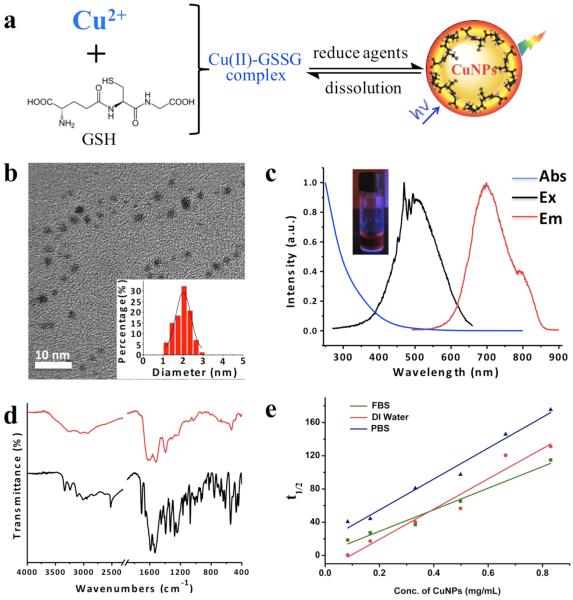

GS-CuNPs were synthesized by reducing Cu(II)-GSSG complexes with NaBH4 (Figure 1a). Once the free GSH and salts were removed, luminescent GS-CuNPs were examined with high-resolution transmission electronic microscope (HRTEM) images, showing a uniform size distribution with the average diameter of 2.0 ± 0.4 nm (Figure 1b). The lattice distance, 2.1 Å, of luminescent GS-CuNPs corresponds to the (111) plane of cubic structured Cu (Figure S1).12 Luminescent GS-CuNPs exhibit near-infrared (NIR) emission with a maximum at 700 nm and a large Stokes shift (~230 nm) (Figure 1c), indicating that metal-to-ligand charge transfer (Cu(I) → GSH) is involved in the emission process.13,14 The HD of luminescent GS-CuNPs measured with a dynamic light scattering (DLS) based particle size analyzer was ~2.7 nm (Figure S2), which was slightly larger than its core size but below the KFT.15–19 To further verify the existence of GSH on the CuNPs, FT-IR spectra were recorded with the purified dry samples of CuNPs (Figure 1d). The typical absorption band of the –COO– group (~1600 cm−1) indicates the successful graft of GSH on the particle surface. Compared to pure GSH, the characteristic absorption peak of the S–H stretching band at 2525 cm−1 disappeared, revealing the interaction between CuNPs and GSH via the deprotonation and coordination of the thiol group.14 Since luminescent GS-CuNPs are chemically unstable and intend to dissociate into smaller nonluminescent copper complexes, their dissociation kinetics were investigated by quantifying their dissociation half-lives (t1/2) in the different chemical environments. The observed linear relationships between t1/2 and the initial concentrations of GS-CuNPs in deionized water (DI H2O), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) solutions suggest that the dissociation of GS-CuNPs is a zero-order reaction in different chemical environments (Figure 1e).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic illustration for the preparation of Cu(II)-glutathione disulfide (GSSG) complex and luminescent copper nanoparticles (CuNPs). (b) TEM image of the monodispersed luminescent CuNPs with GSH as ligand and the statistical core size of luminescent CuNPs from the corresponding TEM images, 2.0 ± 0.4 nm. (c) Absorption, excitation, and emission spectra of GSH-coated luminescent CuNPs. Inset: Luminescent CuNPs under ultraviolet with excitation wavelength of 365 nm. (d) FT-IR spectra of pure GSH (black curve) and GSH-coated luminescent CuNPs (red curve). (e) Dissociation kinetics of GS-CuNPs in different solutions. (R = 0.970, 0.947, 0.977, in FBS, DI water, and PBS, respectively.

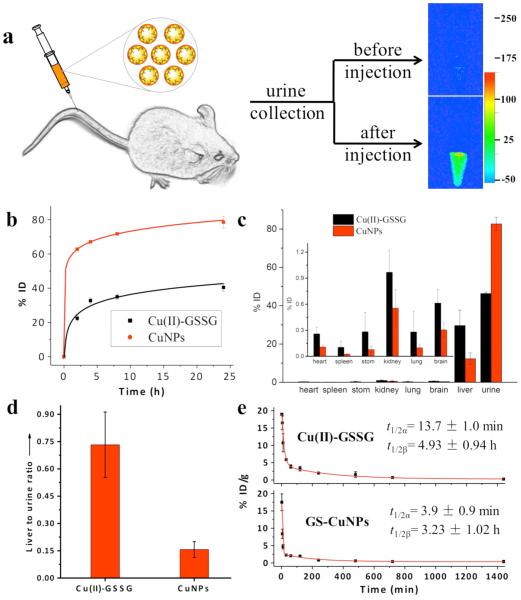

Since “being small” is generally seen as an efficient approach to boosting the clearance of biomaterials from the body,1–3 dissociation fragments and Cu(II)-GSSG complex are expected to be more efficient in renal clearance than their large counterparts, GS-CuNPs.20,21 However, quantitative studies on renal clearance kinetics and biodistribution of GS-CuNPs in BALB/c mice (Figure 2c) show that 78.5 ± 3.5%ID of GS-CuNPs was excreted from the mice into the urine 24 h p.i. and over 60%ID of copper was actually eliminated from the body in the first 2 h p.i. (Figure 2b). On the other hand, the Cu(II)-GSSG complexes were only partially renal-clearable and ~22% ID of copper was found in the urine of the mice injected with Cu(II)-GSSG at 2 h p.i. Interestingly, although GS-CuNPs were much larger than Cu(II)-GSSG complexes, GS-CuNPs were even more efficiently cleared out of the body than the complexes in the first 2 h p.i. Additional increases in urine excretion of copper metal for GS-CuNPs (~16%ID) and Cu(II)-GSSG complexes (~18%ID) after 2 h are comparable (Figure 2b), implying that the major differences in renal clearance efficiencies among CuNPs and Cu complexes originated from the initial clearance stage before the dissociation of GS-CuNPs into Cu(II)-GSSG complex (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Ex vivo fluorescent images of urine collected from mice with or without intravenous injection of luminescent GS-CuNPs 2 h p.i. (λex = 510 nm, λem = 790 nm). (b) Copper contents in the urine at different times post injection (p.i.) (N = 6). (c) Biodistribution of Cu(II)-GSSG complex (300 μL, 0.33 mg/mL) and luminescent GS-CuNPs (300 uL, 0.83 mg/mL) in BALB/c mice 24 h after the tail-vein injection (N = 6). (d) Liver-to-urine ratios of Cu(II)-GSSG complex and GS-CuNPs at 24 h p.i. (e) Pharmacokinetics of Cu(II)-GSSG complex and luminescent GS-CuNPs in 24 h p.i. (N = 6).

The rapid renal clearance of GS-AuNPs is also responsible for significant differences in biodistribution between GS-CuNPs and Cu(II)-GSSG complexes. Compared to free Cu ions that often bind to caeruloplasmin and hephaestin and mainly accumulate in the liver,22 both GS-CuNPs and Cu(II)-GSSG complexes had much lower accumulation in RES organs (Figure 2c), which was because zwitterionic GSH minimized the serum protein absorption and enhanced their renal clearance.4 In addition, the rapid clearance of GS-CuNPs reduced their nonspecific accumulation in RES organs than Cu(II)-GSSG complexes: only 12.3 ± 3.1%ID and ~0.03 ± 0.01%ID of copper was found in the liver and spleen at 24 h p.i., respectively, while Cu(II)-GSSG complex showed remarkably higher accumulation in the liver (29.6 ± 8.1%ID) and spleen (~0.11 ± 0.07%ID). In addition, liver-to-urine ratio (~0.16) of GS-CuNPs is more than 4 times lower than that of Cu(II)-GSSG complex (Figure 2d). The observed low accumulation of GS-CuNPs was also supported by the very short blood elimination half-lives of GS-CuNPs (Figure 2e). Following a rapid distribution with t1/2α of 3.9 ± 0.9 min, GS-CuNPs exhibited a short terminal elimination half-life (t1/2β) of 3.23 ± 1.02 h, similar to many small molecules,23,24 and ~4 times shorter than GS-AuNPs.25 Meanwhile, a slightly slower distribution half-life (t1/2α = 13.7 ± 1.0 min) and relatively longer terminal elimination half-life (t1/2β = 4.93 ± 0.94 h) of Cu(II)-GSSG complex supported the observation in biodistribution and renal clearance, where the copper contents in the organs or tissues were much higher than that of GS-AuNPs (Table S1).

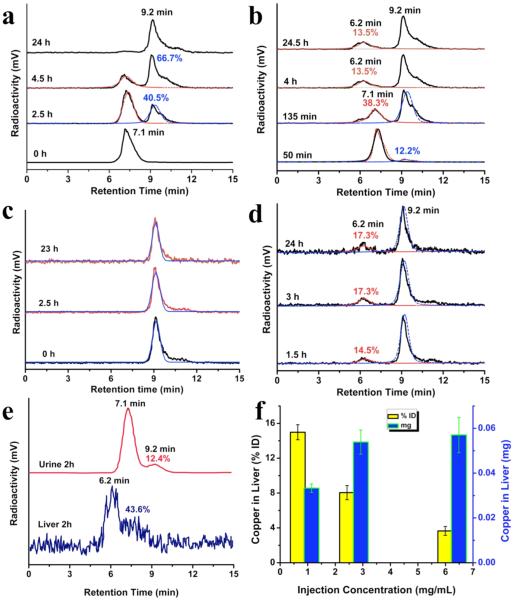

In order to fundamentally understand differences in renal clearance and biodistribution between GS-CuNPs and Cu(II)-GSSG complexes, the physiological stability of GS-CuNPs at the in vitro level was evaluated in details. We employed a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a radioactive detector to track the dissolution behavior of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs, which were prepared by incorporating the trace amount of radioactive 64Cu during the synthesis of GS-CuNPs. Meanwhile, we also synthesized [64Cu]Cu(II)-GSSG complex with a similar approach. As shown in Figure 3a, GS-[64Cu]CuNPs with the retention time of ~7.1 min gradually dissociated into a new product upon incubation with PBS. The dissociation product was later identified as Cu(II)-GSSG complex (Figure 3c) due to its characteristic retention time of ~9.2 min. Nearly 40.5% and 66.7% of the GS-[64Cu]CuNPs in PBS dissociated into Cu(II)-GSSG complex in 2.5 and 4 h, respectively (Figure 3a). In addition, such dissociation of GS-CuNPs into Cu(II)-GSSG complexes was also confirmed by a color change of solution into blue, consistent with the appearance of characteristic absorption of Cu(II)-GSSG complex at 625 nm (Figure S3). To further investigate the stability and interaction of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs in the presence of FBS, the time dependent radioactive HPLC was also recorded. The dissociation of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs in PBS with 10% (v/v) FBS over 4 h resulted in emergence of a new radioactive signal with a retention time of ~6.2 min (Figure 3b). Since both the gel electrophoresis (Figure S4) and radioactive HPLC at 50 min had verified there was no interaction between FBS and GS-[64Cu]CuNPs, this new signal could be likely ascribed to the binding between serum protein and [64Cu]Cu(II)-GSSG complex (~13.5%). Indeed, the same signal also appeared at ~6.2 min with a binding ratio of ~14.5% and ~17.3% when [64Cu]Cu(II)-GSSG complexes were incubated with 10%(v/v) FBS in PBS for 1.5 and 3 h, respectively (Figure 3d). These studies suggested that while GS-CuNPs did not bind to the serum protein, they experienced a gradually dissociation process under the physiological environment and the dissociation products Cu(II)-GSSG complexes partially bound with serum protein.10,11,26 More detailed radioactive HPLC studies on urine and liver samples of a mouse injected with GS-CuNPs at 2 h p.i. showed that ~90% of Cu found in the urine 2 h p.i. were GS-CuNPs while ~60% of Cu found in the liver was Cu(II)-GSSG complexes bound with serum protein (Figure 3e). The differences in binding affinity to serum proteins between GS-CuNPs and their complex fragments are responsible for the observed distinct renal clearance and biodistribution: GS-CuNPs were more easily eliminated from the body through the urinary system because of their low affinity to serum protein adsorption while their fragments intend to bind to serum protein more easily. Additionally, since the dissociation half-life of GS-CuNPs is linearly dependent on the initial GS-CuNP concentrations, liver uptake is affected by initial GS-CuNP concentrations. With the increase of GS-CuNPs injection dose concentrations of copper from 0.89 to 2.68 and 6.24 mg/mL, accumulation of the NPs in the liver was only increased from 0.033 to 0.054 and 0.057 mg, respectively, and the liver uptake compared to total injection doses actually decreased from 14.98% to 8.05% and 3.65%ID, respectively (Figure 3f). Such concentration-dependent liver uptake behavior is distinct from that of those chemically stable NPs such as GS-AuNPs, of which renal clearance of GS-AuNPs is independent of injection doses.4,25

Figure 3.

Time-dependent radioactive high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of (a) CuNPs incubated in PBS, (b) CuNPs incubated in PBS with 10% (v/v) of FBS, (c) Cu(II)-GSSG complex incubated in PBS, (d) Cu(II)-GSSG complex incubated in PBS with 10% (v/v) of FBS. (e) HPLC analysis of liver and urine samples collected at 2 h p.i. (f) Copper uptake in the liver of mice with different injection doses of GS-CuNPs at 24 h p.i.

Dissociation of GS-AuNPs in the physiological environment not only resulted in concentration-dependent renal clearance and liver uptake, but also was responsible for time-dependent biodistribution of GS-CuNPs and Cu(II)-GSSG complexes after i.v. injection. While accumulation of Cu(II)-GSSG complexes in normal tissues and organs is much higher than that of GS-CuNPs in general, the relative differences in biodistribution between the complexes and CuNPs changed with time. For instance, the liver uptake of Cu(II)-GSSG was 9.68 ± 2.56%ID at 1 h p.i., ~5 times higher than that (2.08 ± 0.35%ID) of GS-CuNPs. In addition, the accumulation (7.00 ± 3.90%ID/g) of Cu(II)-GSSG in the muscle is about 9 times than that (0.83 ± 0.32%ID/g) of GS-CuNPs (Figure S5 and Figure S6). However, at 24 h p.i., the liver uptake ratio between Cu(II)-GSSG and GS-CuNPs decreased to 2.5 times, and so did the muscle uptake ratio (~4) (Figure S6). Such changes in copper uptake ratios among different organs were consistent with the renal clearance profile and dissociation kinetics of GS-AuNPs: copper accumulation in the different tissues at the initial stage (1 h. p.i.) was fundamentally governed by intact GS-CuNPs, while it became strongly influenced by their dissociation process of GS-CuNPs at the late injection stage (24 h. p.i).

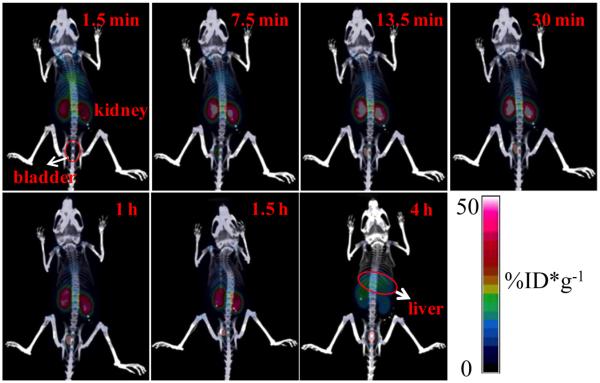

Successful synthesis of renal-clearable GS-[64Cu]CuNPs provided an exciting opportunity to explore a potential biomedical application of CuNPs in PET imaging because 64Cu is a well-known β+ (0.653 MeV, 17.8%) emitter for PET imaging with a half-time of 12.7 h.27–30 In addition, considering copper is a necessary trace element in the human body with the total content of 100–150 mg and ~18 mg in the liver,31 if we could combine renal-clearable CuNPs with highly sensitive nuclear imaging techniques, potential interference induced by endogenous copper in the body can be avoided. To demonstrate such an application, we injected the synthesized radioactive GS-[64Cu]CuNPs into BALB/c mice and performed the PET imaging. Figure 4 demonstrates time-dependent biodistribution of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs during the first 4 h. Consistent with the previous results of GS-CuNPs in the urine, most GS-[64Cu]CuNPs rapidly reached the kidney of BALB/c mice after intravenous injection, followed by excretion to bladder, confirming the prompt renal clearance of the GSCuNPs. Besides the kidney, the intensity in the bladder initially increased sharply and was still preserved at a high level at 4 h p.i., consistent with the results of high content copper in the urine. A slightly high Cu uptake by the liver was observed at 4 h p.i., further implying that the accumulation of copper in the liver was induced by the dissociation of GS-CuNPs into Cu(II)-GSSG complexes.

Figure 4.

Representative microPET-CT images of BALB/c mice at different times after intravenous injection of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs. Note: the percentage injected dose per gram (%ID/g) here is defined as (activity (mCi/mL))/(total injected dose (mCi))/density (assuming density = 1g/mL).

CONCLUSION

In summary, using luminescent GS-CuNPs and their dissociation products, Cu(II)-GSSG complexes as models, we systematically studied their in vitro stability and in vivo behaviors, which show that GSH ligand can significantly enhance renal clearance of CuNPs with an efficiency of 78.5 ± 3.5%ID, 24 h p.i., higher than renal clearance of Cu(II) complexes (40.5 ± 2.3%ID, 24 h p.i.). By incorporating 64Cu into GS-CuNPs and Cu(II)-GSSG during the synthesis, we were able to use radioactive HPLC to in situ quantitatively monitor serum protein adsorption of GS-CuNPs and Cu(II)-GSSG at the in vitro level, which shows that GS-CuNPs have much higher resistance to serum protein adsorption than Cu(II)-GSSG. The observed unique “nano” size effect in enhancing renal clearance of CuNPs might be extended to designing renal-clearable NPs with more diverse diagnosis and therapeutic functionality. In addition, radioactive GS-CuNPs potentially serve as positron emission tomography (PET) contrast agents for kidney imaging. Furthermore, because the dissociation of GS-CuNPs follows zero-order chemical kinetics, the liver uptake can be decreased from 14.98% to 3.65%ID once the injection dose concentration was increased from 0.89 mg/mL to 6.24 mg/mL, which is distinctive of in vivo behaviors of chemically stable inorganic NPs.4,25,29 The fundamental understanding and control of in vivo behaviors of the degradable inorganic NPs will lay down a foundation for further developing renal-clearable inorganic NPs with minimized nanotoxicity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Chemicals and Reagents

Cupric chloride anhydrous (CuCl2), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 12.1 M), and ethanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer was received from Lonza. The 64CuCl2 solution was purchased from University of Wisconsin-Madison. All the other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received unless specified. High-purity water with the resistivity of ~18.2 MΩ*cm was prepared with a Milli-Q water system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

Synthesis of Cu(II)-Glutathione Oxidized (GSSG) Complex

CuCl2 (1 mmol) and GSH (4 mmol) was mixed in 40 mL DI water, followed by adding 5 M NaOH solution to tune the pH of the mixture to about 7, and adding extra DI water to fix the total volume to 50 mL, which was then equally divided into 10 samples in 20 mL vials. The obtained samples were stored at R.T. for about 1 week until the solution color remained unchanged, and the blue Cu(II)-GSSG complex was obtained.

For animal study, the prepared Cu(II)-GSSG complex was precipitated by adding 3× vol ethanol (21 000 g, 1 min). Then, the precipitates were dried by N2 purge and redissolved in PBS, followed by further purifying with gel filtration on an NAP-5 column (GE Healthcare).

Synthesis of Luminescent GS-CuNPs

The synthesized Cu(II)-GSSG complex solution of 4.8 mL was precipitated by adding 3× vol ethanol (21 000 g, 1 min). Then, the precipitates were dried by N2 purge and redissolved in 45 mL DI water, followed by adding freshly prepared 2 mL 4.8 M NaBH4 solution under stirring with the speed of 1150 rpm for 5–10 min. The pH of the solution was then tuned to 4–5 by adding 5 M HCl solution, and the solution was kept at R.T. for ~30 min under stirring.

For animal study, the as-prepared luminescent CuNPs were obtained by the precipitation of sample via adding 2× vol of ethanol (6000 g, 2 min). The precipitates were redissolved in PBS solution, followed by washing 5 times with PBS (10k MWCO, Millipore, 10 000 g, 3 min each time). The obtained solution was then filtered by MWCO (50k MWCO, 10 000 g, 2 min). Finally, the CuNPs was further purified by gel filtration on an NAP-5 column (GE Healthcare), with PBS as the eluent.

Synthesis of Radioactive [64Cu]Cu(II)-GSSG Complex

Radioactive 64CuCl2 (5.9 Gbq/mL, 5 μL) was added into 0.1 mL 0.1 M CuCl2 solution, followed by adding 0.3 mL 0.1 M glutathione oxidized (GSSG) and tuning the pH to ~7 with 1 M NaOH solution. The prepared Cu(II)-GSSG complex was then precipitated by adding 3× vol ethanol (21 000 g, 1 min). The obtained precipitates were dried by N2 purge and redissolved in PBS.

Synthesis of Luminescent Radioactive GS-[64Cu]CuNPs

4.8 mL Cu(II)-GSSG complex solution was precipitated by adding 3× vol ethanol (21 000 g, 1 min). Then, the precipitates were dried by N2 purge, redissolved in 45 mL DI water, and mixed with radioactive 64CuCl2 (6.3 Gbq/mL, 10 μL), followed by adding 2 mL 4.8 M NaBH4 solution under stirring with the speed of 1150 rpm for 5–10 min. The pH of the solution was then tuned to 4–5 by adding 5 M HCl solution, and the solution was kept at R.T. for ~30 min under stirring. The purification procedure of luminescent radioactive GS-[64Cu]CuNPs was the same as the above process of luminescent GS-CuNPs.

Materials Characterization

The luminescence spectra were collected by a PTI QuantaMaster 30 Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Birmingham, NJ). Absorption spectra were collected using a Varian 50 Bio UV–vis spectrophotometer. Particle size and zeta potential in the aqueous solution were determined by a Brookhaven 90Plus Dynamic Light Scattering Particle Size Analyzer (DLS) and a Brookhaven ZetaPALS zeta potential analyzer, respectively. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained from JEOL-2100 transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Nicolet Avatar 360 FT-IR spectrometer. Photographic images of the samples were captured by digital camera (S8100, Nikon). The fluorescence images of urine were acquired using In-Vivo Imaging System FX Pro (Carestream Molecular Imaging) with the excitation and emission wavelength of 510 and 790 nm, respectively.

Gel Electrophoresis

Britton-Robinson buffer (B-R buffer) solution with the pH of 7.4 was prepared as follows: 0.2 M NaOH solution was added into aqueous solution containing 0.04 M phosphoric acid, 0.04 M acetic acid, and 0.04 M boric acid to adjust the pH to 7.4. The as-prepared B-R buffer was diluted 10 times for gel electrophoresis.

The interaction between the luminescent GS-CuNPs and FBS was evaluated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The GS-CuNPs were dissolved in diluted B-R buffer solution at pH 7.4 containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and then incubated in a 37 °C water bath for 30 min. To identify the protein band in the gel, the proteins were stained by Coomassie brilliant blue 250 (CBB250) before the loading of the solution into the gel. Solution (30 μL) of each sample (1: CuNPs + CBB250; 2: CuNPs + FBS + CBB250; 3: CuNPs; 4: CuNPs + FBS) was mixed with 3 μL 75% glycerol and then analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis using the Mini-sub cell GT Gel electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.) and B-R buffer solution at pH 7.4 with 8.5 V cm−1 for 30 min. Pictures were taken under daylight and UV-light with the excitation of 365 nm.

Measuring Dissociation Kinetics of GS-CuNPs in Different Solutions

Luminescence intensities of GS-CuNPs with different concentrations (from ~0.08 mg/mL to ~0.8 mg/mL) in DI H2O, PBS, and FBS were measured at the different time points (20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 130, 160, 200, 280, and 360 min) using a Carestream Molecular Imaging System In-Vivo FX PRO (U.S.). The emission intensities of GS-CuNPs at a specific concentration at the different time points were then fitted with a single exponential decay function. The obtained t1/2 values of GS-CuNPs at the different concentrations were then fitted with a linear function using a standard least-squares regression.

Radioactive High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The dissociation behavior of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs and their interaction with serum protein, as well as the interaction between [64Cu]Cu(II)-GSSG complex and serum protein, were determined by a radio high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The copper concentration of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs and [64Cu]Cu(II)-GSSG complex in each sample (100 μL) was ~0.56 mg/mL and ~0.096 mg/mL, respectively. The HPLC was conducted on a Waters 600 multisolvent delivery system equipped with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector and an in-line Shell Jr. 2000 radio-detector (Fredericksburg, VA). The analysis was performed on a BioSuite 125 SEC HPLC column (10 μm SEC, 7.5 × 300 mm) with 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) as the mobile phase.

Experimental Animals

The animal studies were carried out according to the guidelines of the University of Texas System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The BALB/c mice of 6–8 weeks old, weighing ~20 g, were ordered from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Frederick National Laboratory. The animals were housed in ventilated cages under standard environmental conditions (23 ± 1 °C, 50 ± 5% humidity and a 12/12 h light/dark cycle) with free access to water and standard laboratory food.

Biodistribution Studies of Cu(II)-GSSG Complex and CuNPs

In order to assess tissue distributions of the Cu(II)-GSSG complex and GS-CuNPs, the mice were sacrificed at 1 h, 24 h (N = 6, each group) post IV injection of the samples (300 μL each mouse, copper content was determined by ICP-MS: ~0.83 mg/mL for GS-CuNPs and ~0.33 mg/mL for Cu(II)-GSSG complex). The collected organs were weighed and the metal contents were determined using the ICP-MS method. The blood, tissues, and organs were dissolved in 2 mL 70% nitric acid32,33 in screw-capped glass bottles (20 mL) under sonication for over 12 h, followed by evaporating acid. The residue was then washed by 1% HNO3 with final constant volume of 10 mL and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min to remove precipitates. The resultant clear samples were analyzed by a PerkinElmer-SCIEXELAN 6100 DRC Mass Spectrometry.

Liver Uptake of GS-CuNPs with Different Injection Doses

To study how the injection doses of GS-CuNPs affect their liver uptake, mice were divided into 3 groups and injected with 3 different concentration of GS-CuNPs with copper concentrations of 0.89 mg/mL, 2.68 and 6.24 mg/mL, respectively. At 1 h, 24 h p.i., the mice were sacrificed and the liver tissues were collected. The copper concentration in the liver was characterized with ICP-Mass spectrometry.

Urine Collection and Analysis

To analyze the renal clearance kinetics, the Cu(II)-GSSG complex and GS-CuNPs samples were injected into the mice (N = 6, each group) and the urine was collected at different time points for ICP-MS measurement. For the ICP-MS analysis, the urine was predissolved in the 70 wt % nitric acid and diluted to the suitable concentration.

Radio-HPLC Studies of Cu Components in Urine and Liver at 2 h p.i

GS-[64Cu]CuNPs (~0.88 mg/mL, 250 μL) were intravenously administered to a BALB/c mouse (6–8 weeks old). The urine was collected at 2 p.i. and analyzed with radio-HPLC. The retention times of different peaks were measured. The mouse injected with the NPs was sacrificed at 2 h p.i. after the urine was collected. After liver homogenization with a standard procedure, the homogenate was centrifuged at 21 000g for 5 min and the obtained supernatant fluid was analyzed by radio-HPLC.

Pharmacokinetics Studies of Cu(II)-GSSG Complex and CuNPs

To investigate the pharmacokinetic behavior, BALB/c mice injected with the Cu(II)-GSSG complex or GS-CuNPs were blood sampled from the retro-orbital sinus at 2 min, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h p.i. (N = 3), respectively. The blood samples were analogously processed as organs and urine, and analyzed by ICP-MS. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated based on a two-compartment model, which fit well with biexponential decay.

Micro Positron Emission Tomography (PET)-Computed Tomography (CT) Imaging

The used GS-[64Cu]-CuNPs for PET imaging was synthesized and purified like the previous process with minor modification. Specifically, 0.2 mL Cu(II)-GSSG complex solution was precipitated by adding 3× vol ethanol (21 000g, 1 min). Then, the precipitates were dried by N2 purge, redissolved in 4 mL DI water, and mixed with radioactive 64CuCl2 (5.55 Gbq/mL, 20 μL), followed by adding 0.2 mL 2 M NaBH4 solution under stirring with the speed of 1150 rpm for 5–10 min. Then, the pH of the solution was tuned to 4–5 by adding 1 M HCl solution, and the solution was kept at R.T. for ~30 min under stirring.

In vivo small-animal imaging was performed using a Siemens Inveon PET-CT multimodality system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN) with an intrinsic spatial resolution of 1.5 mm. 6.7 MBq of GS-[64Cu]CuNPs was administered to the BALB/c mouse (6–8 weeks old, 16.8 g) via tail-vein injection. PET images were acquired at 3–4 time points including immediately post injection (p.i.) for 1 h and at 1.5 h, and 4 h p.i. for 15 min. The CT projections (360/rotation) were acquired with a power of 80 kV p, current of 500 μA, exposure time of 145 ms, and binning size of 4. The first 1 h PET images were reconstructed into 20 frames of 180 s using a 3D Ordered Subsets Expectation Maximization (OSEM3D/MAP) algorithm. The 15 min PET images were reconstructed with a single frame and OSEM3D/MAP algorithm. The CT reconstruction protocol used a down sample factor of 2, was set to interpolate bilinearly, and used a Shepp-Logan filter. The PET and CT images were coregistered in Inveon Acquisition Workplace (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN) for analysis. Circular regions of interest (ROI) were drawn manually, encompassing the kidney and bladder in all planes containing the organs. The target activity was calculated as percentage injected dose per gram (%ID/g), which is defined as (activity (mCi/ml))/(total injected dose (mCi))/density (assuming density = 1 g/mL).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the NIH R01DK103363, CPRIT (RP120588, RP140544) and the start-up fund from The University of Texas at Dallas (J.Z.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information The absorption spectrum of Cu(II)-GSSG complex, HR-TEM, DLS, gel electrophoresis results of synthesized CuNPs, and biodistribution data of Cu(II)-GSSG complex and luminescent CuNPs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions Shengyang Yang and Shasha Sun contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Ipe BI, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Liu J, Yu M, Zhou C, Zheng J. Renal clearable inorganic nanoparticles: a new frontier of bionanotechnology. Mater. Today. 2013;16:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Longmire M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: considerations and caveats. Nanomedicine. 2008;3:703–717. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhou C, Long M, Qin Y, Sun X, Zheng J. Luminescent gold nanoparticles with efficient renal clearance. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:3168–3172. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chou LYT, Zagorovsky K, Chan WCW. DNA assembly of nanoparticle superstructures for controlled biological delivery and elimination. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:148–155. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chen Z, Meng HA, Xing GM, Chen CY, Zhao YL, Jia GA, Wang TC, Yuan H, Ye C, Zhao F, Chai ZF, Zhu CF, Fang XH, Ma BC, Wan LJ. Acute toxicological effects of copper nanoparticles in vivo. Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Liu Y, Gao YX, Zhang LL, Wang TC, Wang JX, Jiao F, Li W, Lu Y, Li YF, Li B, Chai ZF, Wu G, Chen CY. Potential health impact on mice after nasal instillation of nano-sized copper particles and their translocation in mice. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2009;9:6335–6343. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Floriano PN, Noble CO, Schoonmaker JM, Poliakoff ED, McCarley RL. Cu(0) nanoclusters derived from poly(propylene imine) dendrimer complexes of Cu(II) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10545–10553. doi: 10.1021/ja010549d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sarkar A, Das J, Manna P, Sil PC. Nano-copper induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in kidney via both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. Toxicology. 2011;290:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Shtyrlin VG, Zyavkina YI, Ilakin VS, Garipov RR, Zakharov AV. Structure, stability, and ligand exchange of copper(II) complexes with oxidized glutathione. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005;99:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Speisky H, Lopez-Alarcon C, Olea-Azar C, Sandoval-Acuna C, Aliaga ME. Role of superoxide anions in the redox changes affecting the physiologically occurring Cu(I)-glutathione complex. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2011:674149. doi: 10.1155/2011/674149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hansen PL, Wagner JB, Helveg S, Rostrup-Nielsen JR, Clausen BS, Topsoe H. Atom-resolved imaging of dynamic shape changes in supported copper nanocrystals. Science. 2002;295:2053–2055. doi: 10.1126/science.1069325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Zhou M, Zhang R, Huang M, Lu W, Song S, Melancon MP, Tian M, Liang D, Li C. A chelator-free multifunctional [64Cu]CuS nanoparticle platform for simultaneous micro-PET/CT imaging and photothermal ablation therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15351–15358. doi: 10.1021/ja106855m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Yang SY, Zhou C, Liu JB, Yu MX, Zheng J. One-step interfacial synthesis and assembly of ultrathin luminescent AuNPs/silica membranes. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:3218–3222. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Choi HS, Liu WH, Liui FB, Nasr K, Misra P, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Design considerations for tumour-targeted nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:42–47. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Alric C, Taleb J, Le Duc G, Mandon C, Billotey C, Le Meur-Herland A, Brochard T, Vocanson F, Janier M, Perriat P, Roux S, Tillement O. Gadolinium chelate coated gold nanoparticles as contrast agents for both X-ray computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5908–5915. doi: 10.1021/ja078176p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gao JH, Chen K, Xie RG, Xie J, Lee S, Cheng Z, Peng XG, Chen XY. Ultrasmall near-infrared non-cadmium quantum dots for in vivo tumor imaging. Small. 2010;6:256–261. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Burns AA, Vider J, Ow H, Herz E, Penate-Medina O, Baumgart M, Larson SM, Wiesner U, Bradbury M. Fluorescent silica nanoparticles with efficient urinary excretion for nanomedicine. Nano Lett. 2009;9:442–448. doi: 10.1021/nl803405h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Park JH, Gu L, von Maltzahn G, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ. Biodegradable luminescent porous silicon nanoparticles for in vivo applications. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:331–336. doi: 10.1038/nmat2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Walkey CD, Olsen JB, Guo HB, Emili A, Chan WCW. Nanoparticle size and surface chemistry determine serum protein adsorption and macrophage uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2139–2147. doi: 10.1021/ja2084338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chou LYT, Chan WCW. Fluorescence-tagged gold nanoparticles for rapidly characterizing the size-dependent biodistribution in tumor models. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2012;1:714–721. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, Dooley JS, Schilsky ML. Wilson's disease. Lancet. 2007:397–408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hao GY, Zhou J, Guo Y, Long MA, Anthony T, Stanfield J, Hsieh JT, Sun XK. A cell permeable peptide analog as a potential-specific PET imaging probe for prostate cancer detection. Amino Acids. 2011;41:1093–1101. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Harrington KJ, Rowlinson-Busza G, Syrigos KN, Uster PS, Abra RM, Stewart JSW. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of In-111-DTPA-labelled pegylated liposomes in a human tumour xenograft model: implications for novel targeting strategies. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;83:232–238. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhou C, Hao G, Thomas P, Liu J, Yu M, Sun S, Oez OK, Sun X, Zheng J. Near-infrared emitting radioactive gold nanoparticles with molecular pharmacokinetics. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:10118–10122. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Han HS, Martin JD, Lee J, Harris DK, Fukumura D, Jain RK, Bawendi M. Spatial charge configuration regulates nanoparticle transport and binding behavior in vivo. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:1414–1419. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sun G, Xu J, Hagooly A, Rossin R, Li Z, Moore DA, Hawker CJ, Welch MJ, Wooley KL. Strategies for optimized radiolabeling of nanoparticles for in vivo PET Imaging. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:3157–+. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhou M, Zhang R, Huang MA, Lu W, Song SL, Melancon MP, Tian M, Liang D, Li C. A chelator-free multifunctional [Cu-64]CuS nanoparticle platform for simultaneous micro-PET/CT imaging and photothermal ablation therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15351–15358. doi: 10.1021/ja106855m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Liu J, Yu M, Ning X, Zhou C, Yang S, Zheng J. PEGylation and zwitterionization: pros and cons in renal clearance and tumor targeting of near-IR-emitting gold nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:12572–12576. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cai WB, Chen K, He LN, Cao QH, Koong A, Chen XY. Quantitative PET of EGFR expression in xenograft-bearing mice using Cu-64-labeled cetuximab, a chimeric anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2007;34:850–858. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE, Gubler CJ. Studies on the function and metabolism of copper. J. Nutr. 1953;50:395–419. doi: 10.1093/jn/50.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Singh P, Prasuhn D, Yeh RM, Destito G, Rae CS, Osborn K, Finn MG, Manchester M. Bio-distribution, toxicity and pathology of cowpea mosaic virus nanoparticles in vivo. J. Controlled Release. 2007;120:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Chen Z, Meng H, Yuan H, Xing G, Chen C, Zhao F, Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhao Y. Identification of target organs of copper nanoparticles with ICP-MS technique. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2007;272:599–603. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.