Abstract

Although the United States faces a seemingly intractable divide between white and African American academic performance, there remains a dearth of longitudinal research investigating factors that work to maintain this gap. The present study examined whether racial discrimination predicted the academic performance of African American students through its effect on depressive symptoms. Participants were a community sample of African American adolescents (N = 495) attending urban public schools from grade 7 to grade 9 (Mage = 12.5). Structural equation modeling revealed that experienced racial discrimination predicted increases in depressive symptoms 1 year later, which, in turn, predicted decreases in academic performance the following year. These results suggest that racial discrimination continues to play a critical role in the academic performance of African American students and, as such, contributes to the maintenance of the race-based academic achievement gap in the United States.

Keywords: Racial discrimination, Academic achievement, African American, Adolescent

1. Introduction

A considerable body of literature evinces that racial discrimination is prevalent, pernicious, and persistent in the lives of African American adolescents (English, Lambert, & Ialongo, 2014; Pachter & García Coll, 2009; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). The stressor has recently been linked to the long-standing race-based academic achievement gap between African American and white adolescents (e.g., English, 2002), which, itself, contributes to disparities in health outcomes, income, and incarceration for African American adults (e.g. Adler & Rehkopf, 2008; Wald & Losen, 2003). In fact, contemporary and historical discrimination based on race have been identified as contributors to what is referred to as the mounting education debt, the culmination of historical, economic, socio-political, and moral factors that promote unequal academic achievement for children of color, particularly African American youth (Ladson-Billings, 2006). While recent cross-sectional research suggests that academic achievement disparities for African American children have been maintained and exacerbated, in part, by experienced racial discrimination and its impact on depressive symptoms (e.g., Wong, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2003), there is a dearth of longitudinal research investigating depressive symptoms as mechanisms through which racial discrimination affects academic performance for African American youth. To address this gap in the literature, the present study investigated depressive symptoms as mediators of a prospective association between racial discrimination experiences and academic performance among a sample of African American youth.

1.1. Models of Racial Discrimination Effects

In this study, racial discrimination is defined as the behavioral manifestation of underlying prejudiced beliefs about African Americans, a component of broader societal racism that operates systematically to distribute power and maintain a social caste system based on racial group membership (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Harrell, 2000; Jones, 1997). Racial discrimination often occurs for African Americans as subtle, insidious, interpersonal slights, referred to as racial microaggressions (Sue, Capodilupo, & Holder, 2008). These personal or vicarious experiences can include being assumed incompetent or unintelligent (e.g., a teacher acting surprised at a positive academic performance), being assumed a criminal (e.g., being watched or followed in a public place), or being treated as a second-class citizen (e.g., being ignored or overlooked at a restaurant) in settings such as school or within the community (Harrell, 2000; Sue et al., 2007).

Several theoretical models place racial discrimination as a critical stressor leading to negative outcomes for African Americans. For instance, the phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST; Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997) posits that African American children and adolescents are exposed to a unique social environment, characterized in part by specific stressors, that affects their psychological and social functioning. PVEST includes experienced racial discrimination as a risk factor to positive social and psychological health for African American adolescents. In particular, PVEST stresses that individual characteristics, such as race, sex, and socioeconomic status, affect the degree to which experienced racial discrimination affects adolescents' developmental outcomes. Similarly, the model presented by García Coll et al. (1996) theorizes that racism and discrimination influence school and neighborhood contexts, child characteristics, and the familial environment, all of which affect the cognitive, social, and emotional developmental outcomes of children and adolescents of color. In addition, in their biopsychosocial model of the experience of racism, Clark et al. (1999) posit constitutional, sociodemographic, psychological, and behavioral factors as moderators of the experience of racism stress. The model stipulates that these factors affect the appraisal of racism and, as such, affect an individual's psychological and physiological stress response and the consequent health outcomes for an individual. The present study, grounded in these theoretical models positing racial discrimination as stressful and developmentally significant for African American youth, investigated racial discrimination as a predictor of psychological symptomatology and negative academic outcomes for African American youth.

1.2. The Education Debt

In her seminal 2006 publication, Gloria Ladson-Billings identified that the term “achievement gap” places the focus of discourse about inequality on individual academic performance isolated in time without considering the various structural inequalities that have worked to maintain disparities and, thus, contribute to what she refers to as an accumulating education debt. As such, she argued that “achievement gap” is not sufficient to describe the disparity in academic performance between African American and white students that has been stark and intractable (English, 2002) throughout the history of integrated schools in the United States (Diamond, 2006; Howard, 2010). Indeed, the race-based disparity in academic achievement has been consistent across time, and in particular over the past two decades, across all age groups and assessments (e.g., Barton & Coley, 2010). These gaps have persisted to today as African American students consistently underachieve in all indicators of academic proficiency. For example, white students averaged 26 points higher than African American students on each subject of the 500-point 2009 National Assessment of Educational Progress scales (NAEP; Vanneman, Hamilton, Anderson, & Rahman, 2009). The 2009 NAEP also indicates there was little to no change in testing performance or GPA gaps through the mid-2000s (e.g., Rampey, Dion, & Donahue, 2009). In fact, in some cases the gap has increased, as in the period from 1990 to 2009 in which the increase in graduates completing a standard high school curriculum was greater for white and Asian/Pacific Islander students than African American students (Nord et al., 2011). These gaps in academic performance have been present throughout the history of public schooling despite there being no evidence for cognitive or biological differences between races that account for differential academic achievement (Jencks & Phillips, 2011). Indeed, in line with the conceptualization of education debt, there is a wealth of evidence indicating that differences in academic achievement across race have clear origins in unique social factors linked to the race of students, such as hypersegregated schools (Wilkes & Iceland, 2004) that bring with them minimal funding for African American students and inadequate schooling conditions (e.g., Baker, Sciarra, & Farrie, 2010). In addition, African Americans are differentially exposed to racial stress and discrimination within schools (Steele & Aronson, 1995), including assessment tools that discriminate based on the test-taker's race (e.g., SAT; Jencks & Phillips, 2011). Gaining a clear understanding of how social factors such as racial discrimination affect the developmental outcomes of African Americans is essential in mitigating the chronic and persistent racial academic achievement gap and, in turn, paying off the racial education debt that has amassed in the United States.

1.3. Depressive Symptoms as a Mechanism Linking Racial Discrimination and Achievement

Recent studies have illustrated a link between racial discrimination and African American adolescent academic achievement. For example, racial discrimination has been linked with decreases in academic engagement, including curiosity, persistence, and student-reported grades (e.g., Neblett, Philip, Cogburn, & Sellers, 2006), and it has been found to reduce positive beliefs about the importance of school, the utility of school, and perceived academic competence (Lambert, Herman, Bynum, & Ialongo, 2009; Wong et al., 2003), all of which are linked to performance in class and on standardized tests (e.g., Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004; Wang & Holcombe, 2010) . In addition, experienced racial discrimination has been negatively associated with academic importance and academic engagement (Chavous, Rivas-Drake, Smalls, Griffin, & Cogburn, 2008).

Several studies suggest that racial discrimination affects academic outcomes for African American adolescents through its effect on depressive symptoms. For example, racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic achievement are associated contemporaneously (e.g., Wong et al., 2003), and racial discrimination has been prospectively linked to African American adolescents' depressive symptoms (e.g. Brody et al., 2006; English et al., 2014), which have been found to predict problems in academics during adolescence (e.g., Birmaher et al., 1996). However, the association between the three constructs has not been tested in a longitudinal model establishing temporal precedence between variables as a strong test of the meditational pathways posited in past theoretical studies (e.g., Clark et al., 1999; García Coll et al., 1996; Spencer et al., 1997). In addition, no past studies have tested multiple meditational pathways to establish the directionality of the associations between racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic achievement for African American adolescents.

1.4. The Present Study

While prior research has provided evidence for cross-sectional links between experiences of racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic performance among African American adolescents, longitudinal research is relatively sparse and methodologically limited. The present study examined a longitudinal mediation model with depressive symptoms as mediators linking the positive prospective association between experienced racial discrimination and academic performance between grades 7 and 9 among a community sample of African American adolescents attending public schools in Baltimore, MD. The following hypotheses were tested: (1) Depressive symptoms will mediate the link between racial discrimination and academic performance, such that increases in racial discrimination will predict increased depressive symptoms which, in turn, will predict decreased achievement scores; (2) the mediated pathway from racial discrimination to decreased achievement scores through greater depressive symptoms will be stronger than alternative meditational models linking experienced racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic achievement across time.

2. Methods

The participants in the present study were drawn from a sample of 678 first-grade students who participated in a multi-year intervention trial through the Johns Hopkins Center for Prevention and Early Intervention program in Baltimore, MD public schools. The intervention program consisted of two classroom-based preventive interventions implemented from 1993–1994 targeting aggressive behavior and learning among first-grade students in three randomly selected classrooms in each of nine Baltimore city public elementary schools, all of which were located in low- to middle-low-income neighborhoods (Ialongo, Kellam, & Poduska, 1999; Ialongo, Werthamer, et al., 1999). One intervention was a classroom-based intervention that included three components: (1) curricular enhancements, (2) improved classroom behavior management practices, and (3) supplementary strategies for children performing under expectations. The other intervention was referred to as the “Family-School Partnership Intervention” aimed to enhance parent–school communication and provide parents with effective teaching and child-behavior management strategies through partnership building activities and workshops. The first and second author were not involved in the data collection, though data collection was directed by the third author. More information on the interventions can be found in Ialongo, Kellam, and Poduska (1999) and Ialongo, Werthamer, et al. (1999). During the years following the initial intervention, the participants completed yearly assessments that included measurements of stress, mental health, and behavioral health and have completed these assessments through to young adulthood. Of the 678 children who participated in the intervention trial in first grade (i.e., in an intervention or control group), 585 were African American. Of these 585 youth, 495 (54% male) participated in the study protocol in grade 7, 8, or 9 during the years 2000–2002. This sample of 495 participants comprised the sample of interest. There was no evidence to suggest that the 90 African American participants who were excluded differed from the 495 African American participants included in this sample with regard to sex (t = −1.20, ns); percentage receiving free or reduced lunch in grade 7 (t = 0.16, ns); age at entry into the study (t = −1.67, ns); depressive symptoms at grade 7 (t = −1.19, ns), grade 8 (t = .50, ns), or grade 9 (t = −.86, ns); racial discrimination at grade 7 (t = .15, ns), grade 8 (t = .12, ns), or grade 9 (t = −.95, ns); or academic performance at grade 7 (t = .62, ns), grade 8 (t = 1.7, ns), or grade 9 (t = .42, ns). Fifty-seven percent of the participants received free/reduced lunch during grade 7. Participants ranged in age from 12 to 14 (M = 12.75, SD = 0.35) at the grade 7 assessment. Of the 495 participants in this study, 32% were in the control group, 34% were in the classroom condition, and 34% were in the family condition. Intervention status was not significantly associated with any of the study variables; thus, it does not appear that the intervention significantly affected the results presented below.

The data featured in the present study were drawn from an existing dataset that spans from the years 1993–2009. We included racial discrimination and depressive symptoms data from early adolescence (grades 7–9 from years 2000–2002), all or part of which has been featured in past publications (e.g., Copeland-Linder, Lambert, Chen, & Ialongo, 2011; English et al., 2014; Lambert et al., 2009). In addition, the academic performance data used in the present study has been featured in previous publications (e.g., Bradshaw, Zmuda, Kellam, & Ialongo, 2009; Ialongo, Kellam and Poduska, 1999; Ialongo, Werthamer, et al., 1999). However, this is the first publication with this dataset to include racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic performance in the same study.

2.1. Procedure

Informed consent from at least one parent and written assent from the student was obtained prior to data collection. Measures of racial discrimination and depressive symptoms were obtained each year from grade 7 to 9 using self-report through face-to-face interviews. Participant grades were assessed through teacher-report in each of grades 7 to 9. Data were collected from the majority of participants (90%) at school during the spring semester of the school year. Youth who had dropped out of school or failed to attend participated in community locations including their home, restaurants, or libraries. Information was collected on experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms by predominantly African American interviewers using Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (ACASI) software.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Demographic information was collected including participant age, sex, and receipt of free or reduced lunch. Intervention status, i.e., control vs. intervention condition, was recorded for each participant. See Table 1 for demographic data.

Table 1.

Demographic data for study participants.

| Variable | N (%) or M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Grade 7 age (years) | 12.75 (.35) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 265 (53%) |

| Female | 230 (47%) |

| Grade 7 lunch status | |

| Paid | 193 (39%) |

| Free/reduced | 281 (57%) |

| Intervention status | |

| Control | 160 (32%) |

| Classroom | 169 (34%) |

| Family | 166 (34%) |

Note. There is a small amount of missing data for each variable.

2.2.2. Experienced Racial Discrimination

Experienced racial discrimination was assessed using 7 items drawn from the Racism and Life Experiences Scales (RaLES; Harrell, 1997, Unpublished manuscript). On this measure, participants indicated how often they and/or a family member had experienced racial discrimination within the past year (e.g., “How often have others reacted to you as if they were afraid or scared because of your race?”; “How often have you or a family member been treated as if you were stupid or talked down to because of your race?”) using a 6-point frequency scale (1 = Never, 2 = Less than once a year, 3 = A few times a year, 4 = About once a month, 5 = A few times a month, 6 = Once a week or more). Please see the supplemental appendix for a full copy of the scale. In Harrell's (1997) development of the RaLES-B, the scale showed concurrent validity as indicated by significant negative correlations with the public subscale of the Collective Self-Esteem (CSE) scale, the identity subscale of the CSE, and a measure of racial identity salience. The experienced racial discrimination variable was included in the model as a latent variable with items as indicators of a single racial discrimination latent variable. One item was excluded from data analysis because it did not significantly load onto the same latent factor as the other six items in the structural equation model (i.e., “How often have you been excluded [left out] from a group activity [game, party, or social event] because of your race?”). This measure has been found to predict depression (English et al., 2014) and aggression (Copeland-Linder et al., 2011) and to correlate with other forms of contextual stress (Copeland-Linder et al., 2011). CFA analyses indicated that the six-item one-factor solution fit the data adequately in grade 7 (χ2(9) = 36.76, p ***< .001; CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.08), grade 8 (χ2(9) = 39.49, p < .001; CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.08), and grade 9 (χ2(9) = 58.40, p < .001; CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA =0.11). Standardized factor loadings across all items ranged from 0.51 to 0.78 in grades 7–9. Because all loadings were positive and loaded onto one latent variable in a similar pattern across the 3 years, there was evidence for configural invariance of the measure across 3 years. In the present study, this scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency as indicated by Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.76 to 0.88 in grades 7–9.

2.2.3. Depressive Symptoms

We assessed depressive symptoms using a 21-item subscale of the Baltimore How I Feel-Adolescent Version, Youth Report (BHIF; Ialongo, Kellam, & Poduska, 1999), a 45-item instrument designed to measure depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth. The depressive symptoms items were constructed based on the criteria for depression from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987), and include items drawn from the Children's Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1983), the Depression Self-Rating Scale (Asarnow & Carlson, 1985), the Hopelessness Scale for Children (Kazdin, Rodgers, & Colbus, 1986), and the Revised-Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1985). The depressive symptoms items require participants to report the frequency with which they have experienced depressive symptoms over the 2 weeks prior to the study using a four-point scale (0 = Never, 1 = Once in a while, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Most times). The BHIF assesses symptoms of depression including anhedonia (e.g., “I had a lot of fun”), depressed mood (e.g., “I felt very unhappy”), and depressive cognitions (e.g., “I felt that it was my fault when bad things happened”). Past studies have found positive associations between scores on the BHIF and a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), self-oriented perfectionism and social prescribed perfectionism (McCreary, Joiner, Schmidt, & Ialongo, 2004), anxiety sensitivity (Lambert, Cooley, Campbell, Benoit, & Stansbury, 2004), and the Emotional Discomfort subscale of the Child Health and Illness Profile Child Edition (Rebok et al., 2001). The BHIF showed good reliability with a Cronbach's alpha for the depressive subscale of 0.83, 0.85, and 0.87 in grades 7, 8, and 9, respectively.

2.2.4. Academic Performance

We assessed academic performance using one item from the Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation—Revised scale (TOCA-R; Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991). In response to the item inquiring about each student's grades in their class over a 3-week period (i.e., “Overall, would you say [child's] grades in your class are…”), teachers rated the participants' academic performance on a 5-point scale (1 = Excellent, 2 = Good, 3 = Fair, 4 = Barely passing, 5 = Failing). Thus, the scale was coded such that lower scores indicated higher performance. This measure has been previously used in several random control trials as a valid indicator of student academic performance, correlating .55 and .60 with the Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills total reading and math score, respectively (e.g., Bradshaw et al., 2009; Ialongo, Kellam and Poduska, 1999; Ialongo, Werthamer, et al., 1999). For this study, scores were averaged across all teachers and academic subjects similarly to how grade point average is calculated across courses for contemporary high school students. For each student, the number of teachers assessed ranged from 1 to 5 teachers with a median number of 2 teacher reports per student for grades 7–9. The mean number of teacher reports in grade 7 was 2.15 (SD = .75), the mean in grade 8 was 1.90 (SD = .65), and the mean in grade 9 was 2.10 (SD = .61).

2.3. Data Analytic Strategy

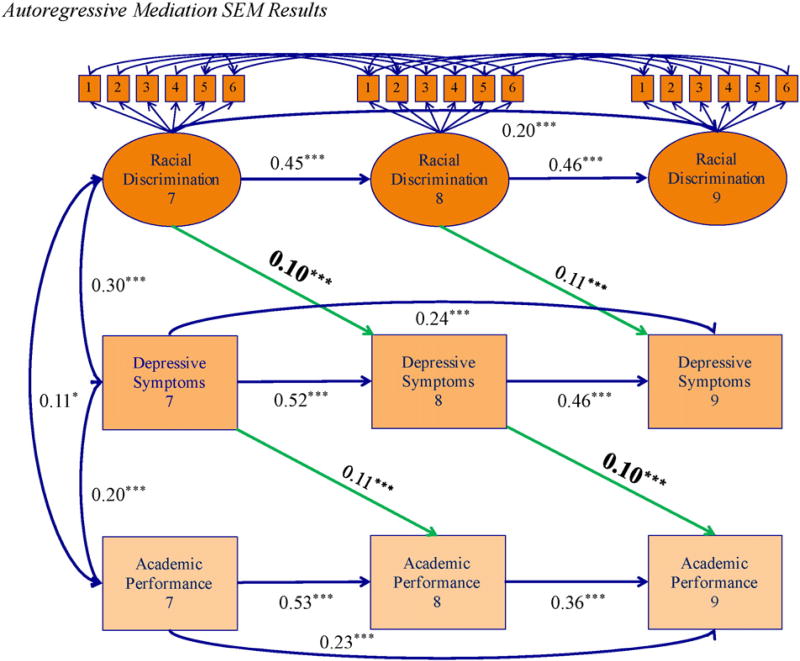

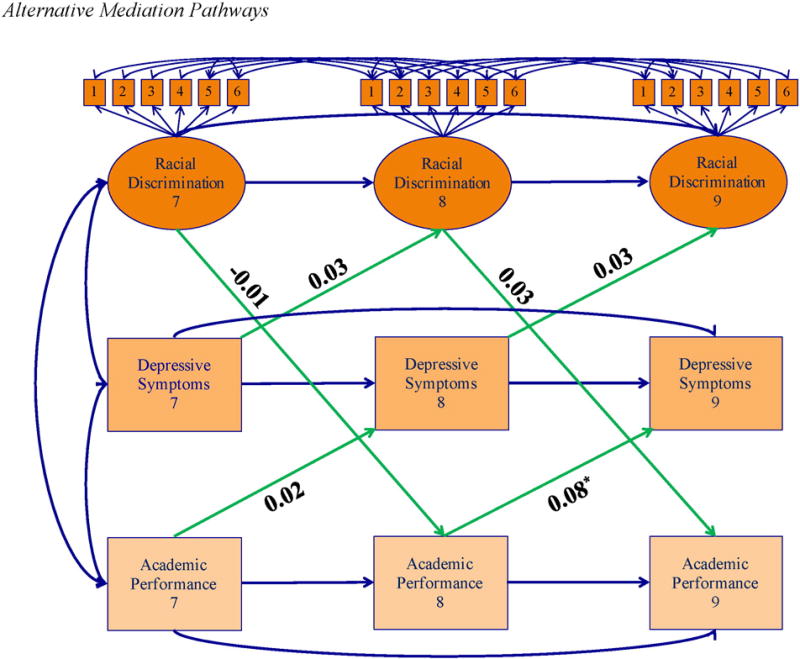

We tested study hypotheses within an autoregressive mediation model analyzed using procedures outlined by Cole and Maxwell (2003). We ran the autoregressive model as a single structural equation model using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), testing the association between a latent experienced racial discrimination variable, an observed mean depressive symptoms variable, and an observed mean academic performance variable while controlling for previous levels of experienced racial discrimination, previous levels of depressive symptoms, previous academic performance, and alternative causal pathways (see Figs. 1 and 2 for all pathways). Model fit was evaluated using the following indicators: Chi-square, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), The Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values above .90 and RMSEA values less than .08 represent acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Fig. 1. Autoregressive mediation SEM results.

Note. 7 = Grade 7; 8 = Grade 8; 9 = Grade 9. Standardized estimates provided. See Results section for information on constraints. Mediation pathway from Hypothesis 1 in bold. Mediation pathways from Hypothesis 2 pictured in Fig. 2. *p ≤ .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 (2-tailed).

Fig. 2. Alternative mediation pathways.

Note. 7 = Grade 7; 8 = Grade 8; 9 = Grade 9. Mediation pathways from Hypothesis 1 pictured in Fig. 1. *p ≤ .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 (2-tailed).

The analysis focused on indirect pathways between racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic performance. Because mediation requires temporal precedence from the independent variable to the mediator to the outcome, we tested the following mediation pathway for hypothesis 1: grade 7 experienced racial discrimination → grade 8 depressive symptoms → grade 9 academic performance. We tested alternative meditational models for hypothesis 2: grade 7 experienced racial discrimination → grade 8 academic performance → grade 9 depressive symptoms; grade 7 depressive symptoms → grade 8 experienced racial discrimination → grade 9 academic performance; and grade 7 academic performance → grade 8 depressive symptoms → grade 9 experienced racial discrimination. These alternative models were tested because they were deemed conceptually plausible and statistically advisable. For example, Cole and Maxwell (2003) suggest that researchers always test the reverse causal direction of the mediation model, which in this study is the grade 7 academic performance → grade 8 depressive symptoms → grade 9 experienced racial discrimination pathway.

In line with the recommendations by Cole and Maxwell (2003), we included autoregressions in the model, controlling for associations between the same variable across adjacent measurements (e.g., grade 7 depressive symptoms → grade 8 depressive symptoms) to account for the stability of each construct over time. Additionally, across all constructs, we ran higher-order autoregressive pathways (e.g., grade 7 measurements → grade 9 measurements). While first-order autoregressions connect consecutive measurements of a construct, i.e., timet → timet+1, higher-order pathways are regressions between measurements of a construct with lag times greater than one wave (e.g., timet → timet+2). These higher-order pathways were included because stationarity, or the assumption that the change process is consistent across repeated time points and completely mediated by adjacent measurements of a single construct (McArdle & Nesselroade, 2014), should not be assumed among youth for which developmental changes are variable during adolescence, particularly because research suggests depression and racial discrimination increase at varying rates during this period (e.g., Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000). We also included synchronous correlations between grade 7 measurements of the independent variable, mediator, and outcome to control for shared predictors. Autoregressions and synchronous correlations within a longitudinal autoregressive model isolate the hypothesized meditational pathways, allowing for a statistically stringent test of the prospective mediation model.

Also in line with the recommendations from Cole and Maxwell (2003), we included prospective pathways that replicated the component pathways of the mediation model at different time points. As such, the model included a path from grade 8 racial discrimination to grade 9 depressive symptoms and a pathway from grade 7 depressive symptoms to grade 8 academic performance. Additionally, in order to control for shared measurement error between adjacent measurements of the same racial discrimination items across years, we included correlations between these items. We also added 3 correlations between adjacent racial discrimination within year that had highly correlated errors (as identified using the MODINDICES function in Mplus). All of these correlations are pictured in Figs. 1 and 2.

To isolate the variance associated with prospective associations within the model and to retain model parsimony (Cole & Maxwell, 2003), a single equality constraint was imposed across the experienced racial discrimination autoregressions and the depressive symptoms autoregressions. This was done as in a previous study using a longitudinal autoregressive structural equation model with the current sample (see English et al., 2014). The corresponding higher-order autoregressions from grade 7 to grade 9 were constrained in the same manner. The autoregressions between measurements of academic performance were allowed to vary freely. In addition, we constrained all of the prospective racial discrimination → depressive symptoms pathways to be equal. We separately constrained all prospective depressive symptoms → academic performance pathways to be equal. None of the equality constraints significantly reduced model fit.

Missing data represents a concern across all longitudinal studies. Among all variables across years, the following were the rates of non-missing data: grade 7 racial discrimination (96%), grade 8 racial discrimination (96%), grade 9 racial discrimination (94%), grade 7 depressive symptoms (96%), grade 8 depressive symptoms (96%), grade 9 depressive symptoms (94%), grade 7 academic performance (91%), grade 8 academic performance (92%), grade 9 academic performance (89%). In the case of missing data, Mplus 7.3 software uses a full information maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption that the data are missing at random (MAR; Arbuckle, 1996), which is a widely accepted way of handling missing data (e.g., Schafer & Graham, 2002). Missing data were handled in line with the Mplus default, using all available data to estimate the model (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). For example, Mplus automatically computes the standard errors for the missing parameter estimates using the observed information matrix (Kenward & Molenberghs, 1998).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Information

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for observed study variables are presented in Table 2. The mean grade rating for the participants was 2.91 in grade 7, 2.90 in grade 8, and 3.20 in grade 9. Practically, this indicates that teachers tended to rate the study participants' grades as “Fair.” The mean depressive symptoms rating was .63 in grade 7, .60 in grade 8, and .62 in grade 9. Practically, this indicates that participants tended to rate their depressive symptoms as occurring between “Never” and “Once in a while.” The mean racial discrimination experiences report was 1.73 in grade 7, 1.78 in grade 8, and 1.91 in grade 9. This indicates that participants tended to report that experiences occurred about “Less than once a year.” As is common in the literature with African American adolescents (e.g., Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006), the distribution for both the depressive symptoms and racial discrimination measures were skewed towards the lower end of their respective scales.

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Racial discrimination (7) | – | ||||||||

| 2. Depressive symptoms (7) | 0.26*** | – | |||||||

| 3. Academic performance (7) | 0.13*** | 0.20*** | – | ||||||

| 4. Racial discrimination (8) | 0.36*** | 0.13** | 0.06 | – | |||||

| 5. Depressive symptoms (8) | 0.18*** | 0.61*** | 0.12*** | 0.20*** | – | ||||

| 6. Academic performance (8) | 0.08 | 0.22*** | 0.55*** | 0.04 | 0.18*** | – | |||

| 7. Racial discrimination (9) | 0.31*** | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.36*** | 0.16** | 0.02 | – | ||

| 8. Depressive symptoms (9) | 0.21*** | 0.56*** | 0.16** | 0.20*** | 0.63*** | 0.20*** | 0.16*** | – | |

| 9. Academic performance (9) | 0.08 | 0.21*** | 0.44*** | 0.07 | 0.18*** | 0.49*** | 0.03 | 0.23*** | – |

| Mean (SD) | 1.73* (0.87) | 0.63 (0.40) | 2.91 (1.04) | 1.78 (0.84) | 0.60 (0.40) | 2.90 (1.04) | 1.91 (0.92) | 0.62 (0.43) | 3.20 (1.09) |

p ≤ .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (2-tailed).

All prospective correlations between consecutive measurements of each construct (e.g., grade 7 racial discrimination with grade 8 racial discrimination) were positive and significant.

Likewise, all correlations between racial discrimination measurements and depressive symptom measurements, except grade 7 depressive symptoms and grade 9 racial discrimination, were positive and significant and all correlations between depressive symptoms and academic performance were positive and significant. No associations between racial discrimination and academic performance were significant other than grade 7 racial discrimination and grade 7 academic performance.

3.2. Mediation Model

The longitudinal autoregressive model (see Fig. 1) provided a good fit to the data, χ2(227) = 379.94, p < .001; CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.04. Consistent with the bivariate correlations, there was stability of experienced racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic performance from grade 7 to grade 9 as evidenced by the significant path coefficients between adjacent measurements of each construct. In addition, all higher-order within-construct autoregressive pathways from grade 7 to grade 9 were positive and significant with effect sizes ranging from .20 to .24. The within-grade 7 correlations between racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic performance were positive and significant (see Fig. 1).

The results provided evidence for the hypothesized meditational pathway. Grade 7 racial discrimination predicted increases in grade 8 depressive symptoms (β = .10, SE = .03, p < .001), and grade 8 depressive symptoms predicted decreases in grade 9 academic performance (β = .10, SE = .03, p < .001). In addition, the specific indirect effect from grade 7 racial discrimination to grade 9 academic performance through grade 8 depressive symptoms was significant (β = .01, SE = .004, p < .01).

There was no evidence for any of the three alternative meditational pathways (see Fig. 2). Grade 7 academic performance did not predict grade 8 depressive symptoms (β = .02, SE = .04, ns), which, in turn, did not significantly predict experienced racial discrimination in grade 9 (β = .03, SE = .04, ns). Grade 7 depressive symptoms did not predict grade 8 experienced racial discrimination (β = .03, SE = .05, ns), and grade 8 experienced racial discrimination did not predict grade 9 academic performance (β = .02, SE = .05, ns). Although grade 8 academic performance predicted increases in grade 9 depressive symptoms (β = .08, SE = .04, p < .05), grade 7 racial discrimination did not predict decreases in grade 8 academic performance (β = −.01, SE = .05, ns), indicating no indirect effect.

4. Discussion

In her commentaries on the race-based achievement gap, Gloria Ladson-Billings (2006, 2013) asserts that it is critical to understand the role of ongoing social factors that help to maintain racial disparities in academic performance and, thus, contribute to the education debt accrued toward African American students. In line with this charge, the present study investigated the link between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms as a predictor of African American academic performance. The results suggest that depressive symptoms are mechanisms through which racial discrimination predicts decreases in academic performance among African American adolescents. Specifically, the results indicated that 1) experienced racial discrimination in grade 7 was positively associated with depressive symptoms in grade 8 which, in turn, predicted a decrease in academic performance in grade 9; and 2) there was no evidence for alternative longitudinal mediation pathways between experienced racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and academic performance. These results suggest that experienced racial discrimination and its associated mental health outcomes continue to contribute to the unrelenting race-based achievement gap in United States public schools and help to maintain a system fostering a centuries-long education debt to African American youth (Ladson-Billings, 2006).

4.1. Experienced Racial Discrimination and Academic Performance

The present results indicate that experienced racial discrimination predicts decreases in academic performance through its influence on depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. These results confirm and extend studies that demonstrate each portion of the mediation model, i.e. racial discrimination → depressive symptoms, and depressive symptoms → low academic performance, separately (e.g., Brody et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2003), and others showing simultaneous cross-sectional associations between these constructs (e.g., Huynh & Fuligni, 2010). The longitudinal nature, the statistical controls, and the testing of alternative causal models included in the present study provide strong evidence that depressive symptoms link experienced racial discrimination and lower academic performance for African American adolescents. These results indicate that the experience of racial discrimination affects the etiology of depressive symptoms and, thus, academic performance as early as 12 years old for African American adolescents. This finding is important because it indicates a process through which African American academic performance is negatively affected, an outcome which predicts racial disparities in income, health outcomes, and incarceration later in life for African Americans (e.g., Adler & Rehkopf, 2008; Wald & Losen, 2003). In combination with past research involving African Americans of varying ages (e.g., Williams & Mohammed, 2009), the present results suggest that racial discrimination can have profound and life-long effects on a multiplicity of developmental outcomes for African Americans.

In one of the alternative mediation pathways tested in the present study, lower grade 8 academic performance significantly predicted increases in grade 9 depressive symptoms, while the reciprocal pathway showed that higher grade 8 depressive symptoms predicted decreases in grade 9 academic performance. This result suggests that there may be a reciprocal longitudinal link between depressive symptoms and academic performance where if one increases, the other decreases, respectively, spurred by the experience of racial discrimination. Such a temporal feedback loop might mean that the effects of racial discrimination build over time and can have increasingly erosive effects the more frequently it is experienced. However, this is a hypothesis for future research to test and is not directly evinced by the present study. Researchers should keep in mind that if such a pattern exists, that it is likely affected by the severity and chronicity of the racial discrimination experiences.

In addition to these outcomes reported in the Results section, it is worth noting that, as with a previous study with this same sample (English et al., 2014), we found that sex moderated the association between experienced racial discrimination and later depressive symptoms such that the link was stronger for females than for males. However, sex did not moderate the link between depressive symptoms and academic performance. Since the significant findings of the moderation analysis had been reported previously, we did not include these in this article's discussion.

It is important to note that the relatively small effect size of the mediational pathway observed in this study (β = .01) highlights that there are many causal processes that affect academic performance for African American adolescents that were not measured. Indeed, although the complexity of the current model is a strong point because it controlled for several sources of error, it also revealed that there was a substantial amount of variance in academic performance not accounted for by our constructs. Conceptually speaking, the idea that racial discrimination and depressive symptoms are just two among many contributors to deficits in academic performance among African American students is in line with Gloria Ladson-Billings' conception of education debt as a problem caused by a multifaceted web of societal and historical marginalization.

4.2. Implications for Prevention and Policy

The present results suggest that in order to reduce the achievement gap between white and African American students and pay off the mounting education debt, the issue of experienced racial discrimination must be addressed in schools. That is, legislators, school administrators, and school staff must be willing to address racial discrimination as a real and meaningful stressor affecting their students. This is critical as research suggests that teachers and school staff often do not recognize, or feel ill-equipped to deal with, race-related issues within a school environment and, as result, choose not to engage it (e.g., Young, 2003). This fact is concerning because 83% of classroom teachers in grades 9–12 are white (Staklis & Henke, 2013) and, as such, likely have not had experience confronting issues associated with racial discrimination in their personal or professional lives (see Rothenberg, 2004). This avoidance of racial topics is problematic, as research with college-aged students suggests that the best way to deal with racial discrimination in a classroom environment is for teachers to directly legitimize discussions about race (e.g., Sue, Lin, Torino, Capodilupo, & Rivera, 2009). The present findings indicate that, without intervention, experienced racial discrimination, a stressor regularly perpetrated by peers and teachers (e.g., Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006), leads to both negative psychological and academic outcomes for African American youth. Thus, cultural competence programming in schools must be a central element in school staff trainings (see Arredondo, 1999; Constantine & Sue, 2006; Laszloffy & Hardy, 2000; Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992 for information on cultural competency programming). In particular, in light of the present study, school counselors and therapists who are often tasked with treating psychological symptoms among individual students and mediating interpersonal conflicts must be able to address issues of race and racial discrimination in order to prevent their associated symptoms.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Through the examination of a meditational pathway from experienced racial discrimination to academic performance through depressive symptoms, the present study provides essential information on the disease process through which racial discrimination affects a critical developmental outcome for African American youth. However, some limitations are worth noting. First, the participants in the present study were all attending urban, predominantly African American schools, limiting its application to African Americans in other school environments. In addition, different reference periods were used for depressive symptoms questionnaire (2 weeks; i.e., “Over the past 2 weeks…”), the experienced racial discrimination questionnaire (1 year; i.e., “Over the past year…”), and academic performance (1 year; “Over the past year…”), meaning that the lag-time between predictors and outcomes could vary based on the timing of these variables within each reference period. Thus, the length of time and the order in which the longitudinal stress process progressed among our participants are not clear. In addition, racial discrimination and depressive symptoms measures were self-report instruments, risking a common method bias in the present results. Both of the frequency estimates for these measures were also negatively skewed in the present study, suggesting that, as with past studies with African American youth (e.g., Sellers et al., 2006), these self-report measures may have underestimated the prevalence of these constructs among our sample of African American youth. The academic performance measure was based on teacher-report, with a variable number of reports across year and participant, rather than academic transcripts, and therefore may have been skewed based on factors such as teacher recall error and academic subject representation. Additionally, because this measure was an aggregate of teacher ratings across academic subjects, it masked relative strengths and weaknesses specific to an academic area. Another issue with the present research was that the racial discrimination measure in the present study conflates both personal and vicarious experiences, as 5 items ask about both individual and familial experiences. In addition, as with the majority of previous studies investigating racial discrimination among adolescents (e.g., Brody et al., 2006; Nyborg & Curry, 2003), our study relied on an instrument that did not include a comprehensive set (i.e., 6 items) of common experiences specific to adolescents. Racial discrimination research will benefit from the construction of developmentally appropriate measures of racial discrimination that assess experiences of racial discrimination that are common among adolescents, such as racial teasing (Douglass, Mirpuri, English, & Yip, 2016). Assessments of experienced racial discrimination specifically within a school context will be particularly important for studying academic performance. Although we did not test the effect of the severity and chronicity of racial discrimination over time, this is a critical area of future of racial discrimination research. It is also essential that future research test the effectiveness of school-based cultural competency programming as a prevention mechanism and buffer against the negative academic outcomes resulting from the racial discrimination → depressive symptoms association.

4.4. Conclusion

The present study provides valuable insight into the role of racial discrimination in the persistence of the racial academic achievement gap across time and, as such, the accumulation of the national education debt (Ladson-Billings, 2006, 2013) owed to African American students. The results indicate that racial discrimination affects academic performance through its impact on the depressive symptoms of these students. Thus, in order to rectify the seemingly intractable racial academic achievement gap separating African American students and their white counterparts, racial discrimination and its associated mental health out-comes must be addressed within schools.

5. Rales-B Measure Items

Adapted from Harrell, S.P. (1997). The Racism and Life Experiences Scales. Unpublished manuscript.

Response scale: Less than once a year, 2 = A few times a year, 3 = About once a month, 4 = A few times a month, 5 = Once a week or more.

How often have you or a family member been ignored, overlooked, or not given service in a restaurant or store because of your race?

How often have you or a family member been treated rudely or disrespectfully because of your race?

How often have others reacted to you as if they were afraid or scared because of your race?

How often have you or a family member been watched or followed while in public places, like stores or restaurants, because of your race?

How often have you or a family member been treated as if you were stupid or talked down to because of your race?

How often have you or a family member been insulted or called a name because of your race?

How often have you been excluded (left out) from a group activity (game, party, or social event) because of your race?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH057005: PI Ialongo; MH078995: PI Lambert) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA11796: PI Ialongo; DA036288: PI English). We thank the Baltimore City Public Schools for their collaborative efforts and the parents, children, teachers, principals, school psychologists, and social workers who participated in this study. We hope that this article helps to amplify your experiences and voices.

References

- Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. US disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (3rd ed., Revised) Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques. 1996:243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo P. Multicultural counseling competencies as tools to address oppression and racism. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1999;77(1):102–108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02427.x. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Carlson GA. Depression self-rating scale: utility with child psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:491–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.491. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BD, Sciarra DG, Farrie D. Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card. Education Law Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barton PE, Coley RJ. Policy Information Report. Educational Testing Service; 2010. The black-white achievement gap: when progress stopped. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, Nelson B. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(11):1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw CP, Zmuda JH, Kellam SG, Ialongo NS. Longitudinal impact of two universal preventive interventions in first grade on educational outcomes in high school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101(4):926–937. doi: 10.1037/a0016586. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: a five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavous TM, Rivas-Drake D, Smalls C, Griffin T, Cogburn C. Gender matters, too: the influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(3):637–654. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(4):558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantine MG, Sue DW. Factors contributing to optimal human functioning in people of color in the United States. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34(2):228–244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000005281318. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland-Linder N, Lambert SF, Chen YF, Ialongo NS. Contextual stress and health risk behaviors among African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(2):158–173. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9520-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9520-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JB. Still separate and unequal: examining race, opportunity, and school achievement in “integrated” suburbs. The Journal of Negro Education. 2006;75(3):495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass S, Mirpuri S, English D, Yip T. “They were just making jokes”: ethnic/racial teasing and discrimination among adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2016;22(1):69–82. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English FW. On the intractability of the achievement gap in urban schools and the discursive practice of continuing racial discrimination. Education and Urban Society. 2002;34(3):298–311. [Google Scholar]

- English D, Lambert SF, Ialongo NS. Longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(4):1190–1196. doi: 10.1037/a0034703. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29(6):679–695. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1026455906512. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational research. 2004;74(1):59–109. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CT, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, García HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. The Racism and Life Experiences Scales (RaLES-Revised). Unpublished manuscript. Culver City, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard TC. Why Race and Culture Matter in schools: Closing the Achievement Gap in America's Classrooms. Teachers College Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, Fuligni AJ. Discrimination hurts: the academic, psychological, and physical well-being of adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(4):916–941. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00670.x. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Kellam G, Poduska J. Manual for the Baltimore How I Feel (Tech.Rep. No 2) Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 1999b. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Werthamer L, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Wang S, Lin Y. Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behavior. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999a;27:599–641. doi: 10.1023/A:1022137920532. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022137920532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Phillips M. The black-white test score gap. Brookings Institution Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM. Prejudice and racism. McGraw-Hill Humanities, Social Sciences & World Languages 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Rodgers A, Colbus D. The hopelessness scale for children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54(2):241–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward MG, Molenberghs G. Likelihood based frequentist inference when data are missing at random. Statistical Science. 1998;13(3):236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children's Depression Inventory: A Self-Rated Depression Scale for School-Age Youngsters. Unpublished Manuscript. University of Pittsburgh; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings G. From the achievement gap to the education debt: Understanding achievement in US schools. Educational Researcher. 2006;35(7):3–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X035007003. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings G. “Stakes is high”: educating new century students. The Journal of Negro Education. 2013;82(2):105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Cooley MR, Campbell KD, Benoit MZ, Stansbury R. Assessing anxiety sensitivity in inner-city African American children: psychometric properties of the childhood anxiety sensitivity index. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(2):248–259. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Herman KC, Bynum MS, Ialongo NS. Perceptions of racism and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents: the role of perceived academic and social control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(4):519–531. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9393-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9393-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszloffy TA, Hardy KV. Uncommon strategies for a common problem: addressing racism in family therapy. Family Process. 2000;39(1):35–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39106.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Structural Equation Models. American Psychological Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCreary BT, Joiner TE, Schmidt NB, Ialongo NS. The structure and correlates of perfectionism in African American children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(2):313–324. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User's Guide. 7. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Philip CL, Cogburn CD, Sellers RM. African American adolescents' discrimination experiences and academic achievement: racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32(2):199–218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0095798406287072. [Google Scholar]

- Nord C, Roey S, Perkins R, Lyons M, Lemanski N, Brown J, Schuknecht J. Results of the 2009 NAEP High School Transcript Study. NCES 2011-462. National Center for Education Statistics; 2011. The Nation's Report Card [TM]: America's High School Graduates. [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg VM, Curry JF. The impact of perceived racism: psychological symptoms among African American boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(2):258–266. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, García Coll C. Racism and child health: a review of the literature and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP. 2009;30(3):255–263. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ed5a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ed5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampey BD, Dion GS, Donahue PL. NCES 2009-479. National Center for Education Statistics; 2009. NAEP 2008: trends in academic progress. [Google Scholar]

- Rebok G, Riley A, Forrest C, Starfield B, Green B, Robertson J, Tambor E. Elementary school-aged children's reports of their health: a cognitive interviewing study. Quality of Life Research. 2001;10(1):59–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1016693417166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1016693417166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised children's manifest anxiety scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg PS. White Privilege: Essential Readings on the Other Side of Racism. Macmillan: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: the relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):187–216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, Hartmann T. A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): a self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9(04):817–833. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staklis S, Henke R. Stats in Brief. NCES 2014-002. National Center for Education Statistics; 2013. Who Considers Teaching and Who Teaches? First-Time 2007-08 Bachelor's Degree Recipients by Teaching Status 1 Year after Graduation. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Arredondo P, McDavis RJ. Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: a call to the profession. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1992;70(4):477–486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01642.x. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Holder A. Racial microaggressions in the life experience of black Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39(3):329–336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.329. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist. 2007;62(4):271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Lin AI, Torino GC, Capodilupo CM, Rivera DP. Racial microaggressions and difficult dialogues on race in the classroom. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(2):183–190. doi: 10.1037/a0014191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanneman A, Hamilton L, Anderson JB, Rahman T. Statistical Analysis Report. NCES 2009-455. National Center for Education Statistics; 2009. Achievement gaps: how black and white students in public schools perform in mathematics and reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Wald J, Losen DJ. Defining and redirecting a school-to-prison pipeline. New Directions for Youth Development. 2003;99:9–15. doi: 10.1002/yd.51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/yd.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MT, Holcombe R. Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal. 2010;47(3):633–662. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0002831209361209. [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam S, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19(4):585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes R, Iceland J. Hypersegregation in the twenty-first century. Demography. 2004;41(1):23–36. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dem.2004.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents' school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71(6):1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G. Dealing with difficult classroom dialogues. In: Bronstein P, Quina K, editors. Teaching Gender and Multicultural Awareness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 337–360. [Google Scholar]