Abstract

Aim

To identify impairment in functional capacity associated with complicated and non-complicated diabetes using the 6-min walk distance test.

Methods

We enrolled 111 adults, aged ≥40 years, with Type 2 diabetes from a hospital facility and 150 healthy control subjects of similar age and sex from a community site in Lima, Peru. All participants completed a 6-min walk test.

Results

The mean age of the 261 participants was 58.3 years, and 43.3% were male. Among those with diabetes, 67 (60%) had non-complicated diabetes and 44 (40%) had complications such as peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy or nephropathy. The mean unadjusted 6-min walk distances were 376 m and 394 m in adults with and without diabetes complications, respectively, vs 469 m in control subjects (P<0.001). In multivariable regression, the subjects with diabetes complications walked 84 m less far (95% CI -104 to -63 m) and those without complications walked 60 m less far (-77 to -42 m) than did control subjects. When using HbA1c level as a covariate in multivariable regression, participants walked 13 m less far (-16.9 to -9.9 m) for each % increase in HbA1c.

Conclusions

The subjects with diabetes had lower functional capacity compared with healthy control subjects with similar characteristics. Differences in 6-min walk distance were even apparent in the subjects without diabetes complications. Potential mechanisms that could explain this finding are early cardiovascular disease or deconditioning.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a serious physical illness that has become a pandemic. In 2013 it was estimated that 382 million people worldwide had diabetes [1], with ~80 % of the global disability-adjusted life-years being accounted for by people in low- to middle-income countries who are living with the disease [2,3]. It is predicted that by the year 2030, diabetes will be the seventh leading cause of death in the world [1], making it a great public health concern.

Diabetes is often associated with other health complications such as cardiomyopathy, hypertension, lower limb amputation, kidney failure and blindness [4,5]. More importantly, patients with diabetes may experience lower quality of life when compared with healthy individuals, and several studies have underscored the important association between diabetes and lowered functional capacity [6-8]. For example, individuals with diabetes experience smooth skeletal muscle alterations that may contribute to lower peak aerobic capacity [4,9], which can cause physical disability [4], poor physical function and weaker muscles [10]; therefore, it has been recommended that comprehensive strategies of treating Type 2 diabetes mellitus include frequent measures of functional status [11].

The 6-min walk test is a simple, reproducible test, developed by Balke [12], that is used to evaluate the functional status of patients with various diseases such as heart and lung disease [13]. Because of the integrated systems of the body that are required during walking, the 6-min walk test provides information about how the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular and pulmonary systems function. Also, the 6-min walk test allows an individual to choose their own exertion level, and thus it may be a more accurate reflection of an individual’s functional capacity when performing activities of daily living, as compared with other clinical exercise tests such as the shuttle walk test, or the cardiac stress test [13].

Previous clinical and observational studies have reported differences in 6-min walk distance between adults with diabetes and healthy control subjects (Table 1) [14-17]; however, in these studies, the samples of adults with diabetes have been confounded by comorbidities [14,15] or subpopulations [17] and these studies did not compare 6-min walk distance between adults with both complicated and non-complicated diabetes, with that of healthy adults. One study by Latiri et al. [16] compared the 6-min walk distance of adults with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus with that of healthy adults, and did not include other subpopulations, or comorbid illnesses; however, that study sampled individuals living in Northwest Africa only, which may have limited the generalizability of the results to other ethnic and racial groups. The aim of the present study was to compare the 6-min walk distance of patients with and without complicated diabetes with that of healthy individuals who did not have diabetes.

Table 1.

Previous studies that have compared 6-min walk distance for subjects with diabetes with that for healthy control subjects

| 6-min walk distance, m (sd) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Comorbidity | Diabetes | Controls | Difference | P |

| Jegdic et al. [14] | Type 1 diabetes | 601 (86) | 672 (61) | 71 | <0.001 |

| Ingle et al. [15] | Chronic heart failure | 238 (124) | 296 (1310 | 58 | 0.005 |

| Latiri et al. [16] | Non-insulin-dependent diabetes | 566 (81) | 636 (112) | 70 | <0.05 |

| Janevic et al. [17] | Heart disease in women | 184 (122) | 237 (142) | 53 | 0.05 |

Subjects and methods

Study setting

The study population consisted of adults with diabetes and healthy control subjects aged ≥ 40 years living in Lima, Peru. Participants were drawn from two settings: we enrolled adults with established diabetes from a hospital facility and healthy adults from a pre-existing subset of healthy adults identified from a larger population-based study [18,19]. Adults with diabetes were recruited from the outpatient Endocrinology Clinic at Hospital National Cayetano Heredia in Lima, Peru. We also enrolled a random subset of healthy control subjects from a community-based study conducted in Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores, a peri-urban shanty-town located 25 km south of the city centre. The control subjects were found not to have diabetes after a fasting blood glucose test (<126 mg/dl) [18,19]. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, USA, and the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and A.B. PRISMA in Lima, Peru.

Participants

At the hospital, in preparation for study activities, we identified 181 patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes attending outpatient clinic visits. Exclusion criteria for adults with diabetes included daily smoking habit and inability to walk without assistance. A study nurse invited eligible patients to participate in this study. Those who wished to pursue enrolment were provided with a written informed consent form. After providing informed consent, enrollees completed a face-to-face questionnaire and performed a 6-min walk test with a trained investigator.

Using the complete cardiopulmonary phenotype completed as part of a longitudinal evaluation between September 2010 and July 2011, we invited a random subset of 150 community healthy participants aged ≥40 years from a well characterized cohort [18,19] to participate in the present study. Exclusion criteria included: physical disability that impaired walking; self-reported diagnosis of heart failure; diabetes (by either self-report or if fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL); asthma; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; active or a history of pulmonary tuberculosis; prior pulmonary or thoracic surgery; current daily smoking habit; BMI ≥35 kg/m2; and systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg. Healthy participants provided verbal informed consent after our research team read the entire informed consent document to them and any questions were answered.

Clinical evaluations

All adults with diabetes underwent clinical evaluations and pupillometry testing, as previously described [20], to assess retinopathy. Retinopathy was determined by an ophthalmologist through a fundus examination of both eyes to examine the blood vessel architecture after dilation with tropicamide 1% as per standard guidelines [21]. Patients suspected of glaucoma were excluded from the study, regardless of retinopathy status. Peripheral neuropathy was diagnosed by a physician before the study, and the participant’s peripheral neuropathy status was abstracted from medical charts. To test for nephropathy, each participant completed a urine spot test using ChemStrip® Micral Test strips (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) to detect microalbumin levels.

Six-minute walk test

Between June and August 2012, we performed the 6-min walk test indoors along a 24-m corridor in the hospital for the group of adults with diabetes and outdoors along a hard flat course measuring 30 m at a school for the group of healthy control subjects. Small differences in course length have not been shown to affect the 6-min walk test [22]. Likewise, changes between indoor and outdoor course settings have not been shown to significantly affect the 6-min walk distance [23]. In both populations the 6-min walk test was conducted according to the American Thoracic Society standards [13]. Before the test was performed, an investigator measured and recorded height, weight, medications taken that day, and vital signs including pulse oximetry, heart rate, blood pressure and level of dyspnoea and fatigue using the Borg scale [13]. After vital signs were recorded, an investigator read out loud, to each participant, instructions adapted from the American Thoracic Society guidelines. Immediately after the 6-min walk test was completed (i.e. within seconds), vital signs and Borg scale were measured once more.

Definitions

We defined daily smoking as ≥1 cigarette/day, hypertension as having a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg; and nephropathy as microalbuminuria ≥30 mg/l [24-26]. We have previously reported a low prevalence of daily smoking in our study setting [27], which has been corroborated with prevalence studies based on urine cotinine by our group (unpublished data). We defined complicated diabetes as either having diabetic peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy or nephropathy identified clinically.

Biostatistical methods

The primary outcome was 6-min walk distance. Primary risk factors were having diabetes with and without complications (vs control subjects) and HbA1c levels. We conducted a multivariable linear regression to compare 6-min walk distance between subjects with diabetes (with and without complications) and control subjects, adjusting for age, sex, height, resting heart rate, change in heart rate after 6-min walk test, baseline pulse oximetry and BMI. In a separate analysis, we conducted a multivariable linear regression to compare 6-min walk distance by continuous HbA1c levels, adjusting for age, resting heart rate, height, change in heart rate after 6-min walk test, baseline pulse oximetry, and BMI. Statistical analyses were conducted in R (www.r-project.org).

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 331 subjects were invited to participate in the study, but 70 (21%) did not meet the eligibility criteria: 49 declined to participate; two were daily smokers, 18 had glaucoma and one did not complete the 6-min walk test. Of the remaining 261 subjects (69%), 150 were healthy control subjects, 67 had diabetes with no complications and 44 had diabetes complications (i.e. diabetic peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy or nephropathy).

The differences between healthy control subjects and those with and without diabetes complications are summarized in Table 2. When compared with healthy control subjects, adults with and without diabetes complications had similar height, diastolic blood pressure and change in heart rate before and after the 6-min walk test. Self-reported difficulty breathing after the 6-min walk test using the Borg scale was similar among the groups, as well as self-reported fatigue. In contrast, HbA1c, weight, BMI and systolic blood pressure were higher among the subjects with diabetes with and without complications compared with the healthy control subjects. We also observed a higher resting heart rate as well as a higher active heart rate (measured immediately after the 6-min walk test) in subjects with diabetes with and without complications vs the healthy control subjects. The subjects with diabetes were on average older than controls. Pulse oximetry was higher in control subjects than in subjects with diabetes with and without complications.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics of healthy control subjects and subjects with and without diabetes complications

| Controls | Diabetes without complications | Diabetes with complications | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 150 | 67 | 44 | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Male % | 47.3 | 44.2 | 38.5 | 0.54 |

| Age in years, mean (sd) | 56 (10.3) | 59.5 (9.3) | 59.3 (9.8) | 0.02 |

| Anthropometrics and clinical data, mean (sd) | ||||

| Height, cm | 154.4 (8.4) | 155.2 (7.8) | 152.7 (8.4) | 0.3 |

| Weight, kg | 67.0 (9.9) | 71.1 (12.4) | 71.0 (13.8) | 0.02 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.1 (3.3) | 29.5 (4.5) | 30.5 (6.3) | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 116.2 (10.9) | 123.4 (19.0) | 125.8 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 68.8 (7.5) | 69.6 (10.0) | 69.5 (10.4) | 0.75 |

| Pulse oximetry, % | 98.4 (1.3) | 97.8 (1.1) | 97.9 (1.2) | 0.004 |

| Resting heart rate, beats/min | 67.1 (9.1) | 77.7 (9.6) | 77.1 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate at the end of 6-min walk test, beats/min | 71.9 (10.3) | 81.3 (11.9) | 83.5 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| Change in heart rate, beats/min | 4.8 (6.3) | 3.6 (6.4) | 6.3 (7.4) | 0.1 |

| Difficulty breathing after 6-min walk test, Borg scale | 0.26 (0.58) | 0.14 (.46) | 0.36 (0.77) | 0.12 |

| Fatigue after 6-min walk test, Borg scale | 0.51 (0.85) | 0.53 (0.90) | 0.61 (0.85) | 0.77 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 38 | 69 | 78 | |

| HbA1c, % | 5.6 (0.34) | 8.5 (2.2) | 9.3 (2.2) | <0.001 |

anova tests for continuous and chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

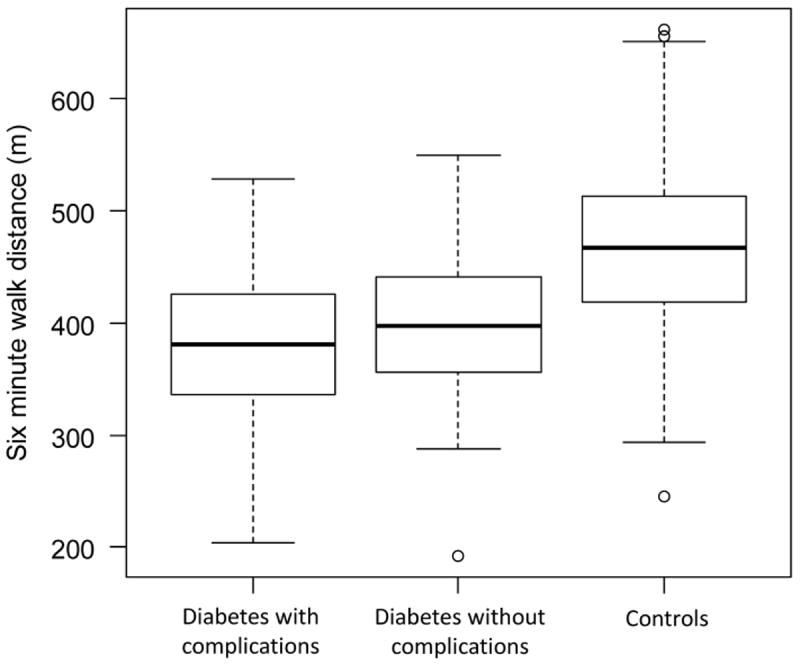

Differences in 6-min walk distance between subjects with diabetes and healthy controls

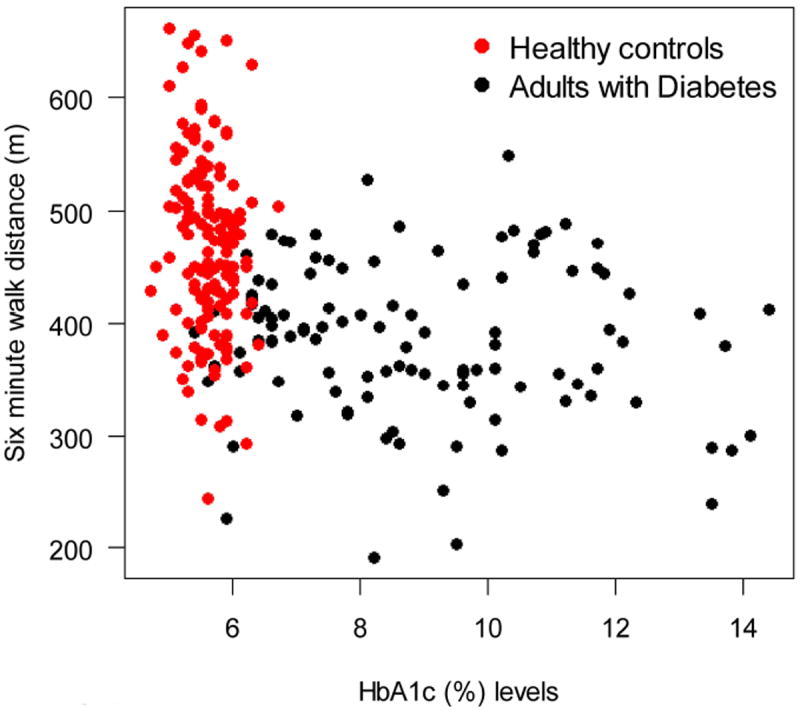

The mean unadjusted 6-min walk distances were 376 m and 394 m in subjects with and without diabetes complications vs 469 m in healthy control subjects (P<0.001), which corresponds to 93 m and 75 m less, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 3). In multivariable linear regression (Table 3), compared with healthy subjects, we found that the adjusted reduction in 6-min walk distance for subjects with diabetes complications was 84 m (95% CI -104 to -63 m; P<0.001) and for those without diabetes complications it was 60 m (95% CI -77 to -42 m; P<0.001). In a second multivariable analysis, we found that 6-min walk distance was 13 m shorter (95% CI -17 m to -10 m) for each 1% increase in HbA1c levels (Table 4).

FIGURE 1.

Boxplot of 6-min walk distance in meters of subjects with and without diabetes complications vs healthy control subjects.

Table 3.

Single variable and multivariable relationships between 6-min walk distance in subjects with non-complicated diabetes vs those with complicated diabetes vs healthy control subjects

| Single variable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference in 6-min walk distance (95% CI) | P | Mean difference in 6-min walk distance (95% CI) | P | |

| Diabetes without complications vs healthy controls | -74.8 (-96.1 to -53.5) | <0.001 | -60.4 (-77.9 to -42.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes with ≥1 complication vs healthy controls | -92.5 (-117.3 to -67.7) | <0.001 | -83.6 (-103.9 to - 63.3) | <0.001 |

| Age per year | -3.3 (-4.2 to -2.3) | <0.001 | -2.7 (-3.5 to -2.0) | <0.001 |

| Females (vs males) | -54.9 (-74.4 to -35.5) | <0.001 | -37.4 (-57.2 to -17.7) | <0.001 |

| Height, per cm | 3.5 (2.3 to 4.6) | <0.001 | 1.43 (0.2 to 2.6) | 0.02 |

| BMI, per kg/m2 | -2.0 (-4.4 to .32) | 0.09 | 0.1 (-1.7 to 2.0) | 0.87 |

| Pulse oximetry, per % | 10.3 (2.2 to 18.5) | 0.01 | 0.05 (-6.2 to 6.3) | 0.99 |

| Change in heart rate before/after 6- min walk test, per beats/min | 3.6 (2.2 to 5.2) | <0.001 | 3.7 (2.6 to 4.8) | <0.001 |

Table 4.

Single variable and multivariable relationships between 6-min walk distance in meters and HbA1c levels for subjects with diabetes and healthy control subjects

| Single variable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference in 6-min walk distance (95% CI) | P | Mean difference in 6-min walk distance (95% CI) | P | |

| HbA1c, per each % increase | -15.6 (-19.9 to -11.2) | <0.001 | -13.4 (-16.9 to -9.9) | <0.001 |

| Age per year | -3.3 (-4.2 to -2.3) | <0.001 | -3.1 (-3.9 to -2.4) | <0.001 |

| Females (vs males) | -54.9 (-74.4 to -35.5) | <0.001 | -33 (-53.7 to -12.3) | 0.002 |

| Height, per cm | 3.5 (2.3 to 4.6) | <0.001 | 1.3 (-0.9 to 2.6) | 0.04 |

| BMI, per kg/m2 | -2.0 (-4.4 to .32) | 0.09 | -1.2 (-3.0 to 0.7) | 0.22 |

| Pulse oximetry, per % | 10.3 (2.2 to 18.5) | 0.01 | 1.5 (-4.9 to 7.9) | 0.65 |

| Change in heart rate before/after 6- min walk test, per beats/min | 3.6 (2.2 to 5.2) | <0.001 | 3.9 (2.7 to 5.0) | <0.001 |

Discussion

The 6-min walk test is commonly used to monitor chronic heart or pulmonary conditions [22], but it also has potential applicability to diabetes as a screen for early cardiopulmonary complications. In the present study, we found a clinically important reduction in 6-min walk distance between subjects with diabetes complications and healthy control subjects after multivariable analysis. On comparison of subjects without diabetes complications with healthy control subjects, the reduction in 6-min walk distance persisted. While the mechanism for this decrease in functional status is unclear, it may be attributable to either early cardiovascular disease or deconditioning [13].

In the present study, we used a population-based sample of healthy control subjects, identified after multiple screening examinations, and a well-established sample of individuals with diabetes from a hospital setting. Our findings suggest that a reduction in 6-min walk distance may precede other overt manifestations of diabetes. Specifically, either a lack of activity or disinclination to exercise leading to deconditioning may, in turn, lead to impairment of glucose tolerance or to cardiopulmonary complications beginning earlier than expected [7,28]. A recent review recommended that individuals with diabetes receive routine surveillance to check functional status [29]. Exercise tolerance is usually measured using cardiopulmonary exercise tests, which require experienced technicians to operate the machinery and substantial financial costs. In contrast, the 6-min walk test is a non-invasive, inexpensive test that can be conducted frequently without incurring major costs.

Previous clinical studies have shown differences in 6-min walk distance between adults with diabetes and healthy control subjects [14-17], but these study populations were confounded by comorbidities or subpopulations. A study conducted by Jegdic et al. [14] found that children with Type 1 diabetes walked 71 m less far (601 m vs. 672 m) than those without diabetes, and the authors concluded that children with Type 1 diabetes were less physically fit than matched healthy control subjects. In another study by Ingle et al. [15], patients with heart failure and diabetes walked 58 m less far (238 m vs. 296 m) than did those with heart failure but without diabetes, and the authors concluded that diabetes may be an independent determinant of decreased functional performance in patients with heart failure. Finally, Latiri et al. [16] found that adults with Type 2 diabetes walked 70 m less far (566 m vs. 636 m) than the healthy control subjects.

The present study has some limitations. First, our sample size was moderate and did not allow us to study interaction effects between variables. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to conclude causation of the lowered 6-min walk distance among adults with diabetes. Third, we also lacked lung function data on adults with diabetes to control for potential pulmonary complications. Fourth, we lacked data regarding potential therapies that adults with diabetes may have been receiving during the time of the study. Fifth, while small changes in course length as well as course setting have not been shown to affect the 6-min walk distance significantly [22,23], the fact that both samples did not walk the same course was a limitation. Sixth, for the adults with diabetes, we did not have information on socio-economic status, which has also been shown to contribute to 6-min walk distance [11,16,18]. Finally, while there were differences in age and other variables (BMI, systolic blood pressure, resting heart rate and pulse oximetry) between adults with and without diabetes, there was substantial overlap that allowed adequate adjustment in a multivariable analysis.

In summary, there remained a significant difference in 6-min walk distance between the subjects with and without diabetes complications vs the healthy control subjects after stratifying for variables shown to be associated with the 6-min walk test. These 84- and 60-m differences in subjects with and without diabetes complications vs healthy control subjects, respectively, is greater than the minimally important difference of 25–45 m observed in previous studies [30,31], which may indicate early cardiovascular impairment or deconditioning among adults with diabetes.

FIGURE 2.

Scatterplot of 6-min walk distance in meters vs HbA1c levels for subjects with diabetes (black circles) and healthy control subjects (red circles).

What’s new?

In this study we identified impairment in functional capacity among adults with complicated and non-complicated diabetes using the 6-min walk test.

We sought to show the potential clinical use of the 6-min walk test in the assessment and care of adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

We found a statistically significant difference in 6-min walk distance between healthy adults and adults with and without complicated diabetes

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This project was funded in part with Federal funds from the United States National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN268200900033C. William Checkley was further supported by a Pathway to Independence Award (R00HL096955) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Diabetes: a look to the future. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:e1–2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narayan KM, Zhang P, Kanaya AM, Williams DE, Engelgau MM, Imperatore G, et al. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Diabetes: The Pandemic and Potential Solutions. World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginter E, Simko V. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, pandemic in 21st century. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;771:42–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-5441-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohlendieck K. Pathobiochemical changes in diabetic skeletal muscle as revealed by mass-spectrometry-based proteomics. J Nutr Metab. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/893876. 893876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sander GE, Giles TD. Diabetes mellitus and heart failure. Am Heart Hosp J. 2003;1:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-9215.2003.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell BD, Stern MP, Haffner SM, Hazuda HP, Patterson JK. Functional impairment in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites with diabetes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:319–327. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estacio RO, Regensteiner JG, Wolfel EE, Jeffers B, Dickenson M, Schrier RW. The association between diabetic complications and exercise capacity in NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:291–295. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregg EW, Mangione CM, Cauley JA, Thompson TJ, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Diabetes and incidence of functional disability in older women. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:61–67. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tibb AS, Ennezat PV, Chen JA, Haider A, Gundewar S, Cotarlan V, et al. Diabetes lowers aerobic capacity in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:930–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayer AA, Dennison EM, Syddall HE, Gilbody HJ, Phillips DI, Cooper C. Type 2 diabetes, muscle strength, and impaired physical function: the tip of the iceberg? Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2541–2542. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Grauw WJ, van de Lisdonk EH, Behr RR, van Gerwen WH, van den Hoogen HJ, van Weel C. The impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on daily functioning. Fam Pract. 1999;16:133–139. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balke B. A simple field test for the assessment of physical fitness. Rep Civ Aeromed Res Inst US. 1963:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jegdic V, Roncevic Z, Skrabic V. Physical fitness in children with type 1 diabetes measured with six-minute walk test. Int J Endocrinol. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/190454. 190454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingle L, Reddy P, Clark AL, Cleland JG. Diabetes lowers six-minute walk test performance in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1909–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latiri I, Elbey R, Hcini K, Zaoui A, Charfeddine B, Maarouf MR, et al. Six-minute walk test in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients living in Northwest Africa. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2012;5:227–245. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S28642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janevic MR, Janz NK, Connell CM, Kaciroti N, Clark NM. Progression of symptoms and functioning among female cardiac patients with and without diabetes. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:107–115. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miranda JJ, Bernable-Ortiz A, Smeeth L, Gilman RH, Checkley W CRONICAS Cohort Study Group. Addressing geographical variation in the progression of non-communicable disease in Peru: the CRONICAS cohort study protocol. BMJ. 2012;Open 2:000610. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caffrey D, Miranda JJ, Gilman RH, Davila-Roman VG, Cabrera L, Dowling R, et al. A cross-sectional study of differences in 6-min walk distance in healthy adults residing at high altitude versus sea level. Extrem Physiol Med. 2014;3:3. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerner A, Bernabé-Ortiz A, Ticse R, Hernandez A, Huaylinos Y, Pinto M, et al. Type 2 diabetes and cardiac autonomic neuropathy screening using dynamic pupillometry. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1470–1478. doi: 10.1111/dme.12752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL, Klein RE, Lee PP, Agardh CD, Davis M, et al. Proposed International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema Disease Severity Scales. Opthalmology. 2003;110:1677–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sciurba F, Criner GJ, Lee SM, Mohsenifar Z, Shade D, Slivka W, et al. Six-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: reproducibility and effect of walking course layout and length. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1522–1527. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-166OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks D, Solway S, Weinacht K, Wang D, Thomas S. Comparison between an indoor and an outdoor 6-minute walk test among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2003;84:873–876. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derhaschnig U, Kittler H, Woisetschläger C, Bur A, Herkner H, Hirschl MM. Microalbumin measurement alone or calculation of the albumin/creatinine ratio for the screening of hypertension patients? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:81–85. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meinhardt U, Ammann RA, Flück C, Diem P, Mullis PE. Microalbuminuria in diabetes mellitus: efficacy of a new screening method in comparison with timed overnight urine collection. J Diabetes Complications. 2003;17:254–257. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams BT, Ketchum CH, Robinson CA, Bell DS. Screening for slight albuminuria: a comparison of selected commercially available methods. South Med J. 1990;83:1447–1449. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199012000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weygandt PL, Vidal-Cardenas E, Gilman RH, Avila-Tang E, Cabrera L, Checkley W. Epidemiology of tobacco use and dependence in adults in a poor peri-urban community in Lima, Peru. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seyoum B, Estacio RO, Berhanu P, Schrier RW. Exercise capacity is a predictor of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3:197–201. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin S, Kinmonth AL. Diabetes care: the effectiveness of systems for routine surveillance for people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000541. CD000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland AE, Nici L. The return of the minimum clinically important difference for 6-minute-walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:335–336. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2191ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathai SC, Puhan MA, Lam D, Wise RA. The minimal important difference in the 6-minute walk test for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;3:428–433. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0480OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]