Abstract

LATINOS COMPRISE THE LARGEST MINORITY RURAL POPULATION IN THE U.S. AND THEY ARE OFTEN EXPOSED TO ADVERSE SOCIAL HEALTH DETERMINANTS THAT CAN DETRIMENTALLY AFFECT THEIR MENTAL HEALTH. GUIDED BY THE CBPR PRINCIPLES, THIS STUDY AIMED TO DESCRIBE FBO LEADERS’ PERCEPTIONS OF THE CONTEXTS AFFECTING MENTAL WELL-BEING AND POTENTIAL APPROACHES TO MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION IN RURAL, LATINO IMMIGRANTS. THIS IS A DESCRIPTIVE, QUALITATIVE ARM OF A LARGER STUDY IN WHICH COMMUNITY-ACADEMIC MEMBERS HAVE PARTNERED TO DEVELOP A CULTURALLY TAILORED MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION INTERVENTION AMONG RURAL LATINOS. FBO’S LEADERS (N=15), FROM DIFFERENT DENOMINATIONS IN NORTH FLORIDA, WERE INTERVIEWED UNTIL SATURATION WAS REACHED. FBO LEADERS REMARKED THAT IN ADDITION TO RELIGIOSITY, WHICH LATINOS ALREADY HAVE, MORE COMMUNITY BUILDING AND INVOLVEMENT IS NECESSARY TO THE PROMOTION OF MENTAL HEALTH.

INTRODUCTION

U.S. Latino immigrants, a diverse group of people with personal and family roots in Latin American countries, comprise the largest minority rural population; indeed, nearly 3.2 million Latinos live in rural communities with fewer than 2,500 residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Some of these rural areas, known as “new destinations”, reside outside the traditional Latino urban gateways, and may deprive Latinos of significant social capital resources vital to well-being (Shihadeh & Barranco, 2010; Shihadeh & Winters, 2010). In fact, evidence suggests that Latinos in new destinations rely less on established ethnic communities and are vastly isolated from non-Latinos (Leach & Bean, 2008; Lichter, Domenico, Michael, & Stephen, 2010). Latino communities in these new destinations also appear to be qualitatively different from those in traditional settlement states because of adverse social health determinants that can detrimentally affect their health by acting as chronic stressors. According to Healthy People 2020, social determinants of health are social and environmental conditions that shape a wide range of health, functioning and quality of life outcomes. For example, the poverty rate of Latinos is at least twice that of non-Latino adults, and over one-third of Latino children live in poverty (Saenz, 2008). Latinos also experience reduced access to health care due to lack of health insurance and bilingual or bicultural services, leading to significant health disparities within the population (Brennan, Baker, & Metzler, 2008). Social isolation has been linked to emotional distress and increased risk for mental health issues, including depression and anxiety among parents (Hiott, Grzywacz, Davis, Quandt, & Arcury, 2008; Stacciarini, et al., 2014; Stacciarini, Smith, Garvan, Wiens, & Cottler, 2015), which can negatively impact their children’s mental health.

Social determinants, in conjunction with intrafamilial conflict and racism, exacerbate mental health problems in rural Latino families (Vega et al., 1998), particularly over the long-term (Cook, Alegría, Lin, & Guo, 2009). Although these problems demonstrate that U.S. Latino immigrants in rural areas are a vulnerable population, they are still vastly understudied, and mental well-being is often a missing component in health care and community programs.

One way to counteract these negative determinants may be through well-being programs established by Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs), which include churches and other houses of worship. This is because spirituality and religion have historically been constructive elements in Latino communities. For example, Latinos pray and attend church more frequently, see their church community as more supportive, and demonstrate a stronger perception of how religion is connected to daily life than non-Hispanic white Americans (Sternthal, Williams, Musick, & Buck, 2012). Despite the facts that having a religion is recognized as positively affecting mental health in Latinos (Harari, Davis, & Heisler, 2008; Hiott, et al., 2008; Sternthal, et al., 2012), and that FBOs are effective in reducing health disparities (DeHaven, Hunter, Wilder, Walton, & Berry, 2004), few health prevention researchers have partnered with FBOs to promote mental health in rural Latino immigrants (Giarratano, Bustamante-Forest, & Carter, 2005). Also, to our knowledge, interventions that promote mental health among Latinos in rural areas and involve FBOs have not been developed. Thus, this study will help bridge this gap by describing FBO leaders’ perceptions of the psycho-social contexts that affect mental well-being and potential approaches to mental health promotion in rural Latino immigrants. This study originated from a larger, community-based participatory research (CBPR), which aims to promote well-being in the rural Latino community. In this larger research study, academics have partnered with community members and formed a community advisory board (CAB); members of this CAB recommended interviewing FBO leaders because they are “holders of knowledge on rural Latinos,” especially in rural new destinations.

Conceptual Framework

The content of participant interviews was analyzed using a conceptual framework from the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH, 2008). The CSDH encompasses three main elements that can impact health and well-being: 1) Socio-economic and political context, 2) Social context as structural determinants, and 3) Material and behavioral/biological and psychosocial factors. The Structural Determinants (SDs) refer to the interplay between the socio-economic–political contexts and the socio economic position of individuals, which can generate mechanisms that may influence health and well-being. According to this model, SDs associated with key components of social context (SC) are the root of health inequities at the population level. The Intermediary Determinants (IDs) are influenced by the individual, including their health-related behaviors. The ID factors flow from the configuration of underlying social stratification and determine differences in exposure and vulnerabilities to health and deleterious conditions. The social cohesion/social capital concepts are a crosscutting determinant; mainly, they refer to how the resources flow and emerge through social networks (CSDH, 2008).

METHOD

This is a qualitative pilot study, guided by the Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) principles (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). It is one of the arms of a larger study in which community-academic members have collaborated to develop a culturally tailored mental health promotion intervention among rural Latinos in North Florida. In agreement with CBPR principles, CAB members who have been active community insiders and partners of the research team in other studies also collaborated on this pilot by: 1) recommending FBO leaders as a potential resource, 2) helping expand the interview questions, 3) identifying churches with large number of Latinos congregants, 4) endorsing the data collection by referring FBO leaders for interviews and 5) supporting the data analysis plan. These CAB members have been research partners since 2009; they are mostly Latinos and affiliated with well-known and trusted organizations that offer educational, social, and religious services (e.g. public school teachers, public health department staff, church members) in rural areas; data about the CAB research involvement has been presented elsewhere (Stacciarini, 2011).

Community sites and FBOs

Although Florida is considered an immigrant friendly state because of the established Cuban population in Miami, it is now facing an influx of Mexican immigrants settling in “new destinations”; that is, rural areas unused to large numbers of Latino residents (Terrazas, 2010). The community sites for this study were Levy and Lafayette Counties, which are rural areas of North Florida with vast farmland and highly scattered residences. According to the U.S. census (2010), Levy County’s population density is 28 persons per/square mile, including 39,644 residents, and 7.8% are identified as Latinos (Hispanics). Other studies have been developed within the target community (Stacciarini et al., 2011; Stacciarini, et al., 2014; Stacciarini, et al., 2015), and with potential community grassroots support such as FBO leaders, who are the focus of this article. For this study, five FBOs (all churches) from Catholic and Protestant denominations were used. All FBOs had large Latino congregants and were located in rural communities.

Data Collection

After IRB approval, in-depth interviews were performed with priest/pastors and FBO leaders in rural areas of North Florida, to determine ways to approach mental health promotion through church-based interventions. The interview questions sought to identify how FBO leaders perceived the psycho-social health determinants of rural Latinos as well as FBO leader involvement in dealing with other relevant issues. More specifically, leaders were asked questions regarding problems among, support needed by, concerns about, and hopes for the rural Latino community. More specifically, one question was, “Could you please describe what emotional and social problems that the Latino people face in this community?” Another question was, “What type of support could help Latino people to have a better life while living in this rural area?” These questions were developed and pre-tested in conjunction with the community advisory board (CAB) members, who described perceiving mental well-being as having positive emotions as well as high psychological and social functioning.

Based on the recommendations of the CAB members, a community lay-health worker (promotora) was chosen to conduct the interviews. Promotoras are significant community-insiders that can act as culturally appropriate research assistants (Stacciarini et al., 2012). For this project, a bilingual and bicultural promotora was selected from the community and was continually trained by the PI to collect data and meet research requirements, including institutional review board regulations, interview objectivity, and research protocols. Initially, the promotora interviewed the PI and few other students as part of the training; these interviews were video-taped and then watched and discussed. After the first interviews were performed with participants, the PI listened to the interviews, and another training meeting was conducted to enhance the promotora’s interview skills.

To collect the data, the promotora contacted priests/pastors of churches, explained the study, received participants’ consent, and proceeded with the interviews. In all of the churches, priest/pastors of the target FBOs from different denominations were interviewed, and then snow ball sampling was used to interview other “key Latino leaders” in the same church. Data collection was performed in either English or Spanish, depending on participant preference; all interviews were recorded and then transcribed for data analysis. Three leaders of each FBO were interviewed (N=15 participants) until saturation was reached; no thematic variations appeared.

The FBO priest/pastor and other members of the church identified as Latino adults between the ages of 47–72 years. Seven women and eight men participated in the interviews, and two FBOs were Catholic and the others were Protestant. All participants had been involved with religious services for the Latino community for at least 5 years.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis (Ryan & Bernard, 2003) was used to identify common and significant content from the interviews, by using Nvivo 10. All transcripts were analyzed in the original language (Spanish or English). A bilingual researcher and two trained bilingual students independently read and reread all data, examining key words, trends, themes, and ideas to identify major themes. As a team, all of the coders began analysis using main themes of the theoretical framework: 1) Socio-economic and political context, 2) Social context, and 3) Material and behavioral/biological and psychosocial factors, and freely added any new thematic discoveries. Throughout the data analysis, coders met several times to develop a thematic consensus.

All of the categories were further described to the CAB for social validation and to foster mutual understanding (Miles & Huberman, 1994); CAB members were presented with data results and de-identified interview excerpts to illustrate content and maintain richness of findings. Thus, the CAB members functioned as validity auditors of the study analysis.

FINDINGS

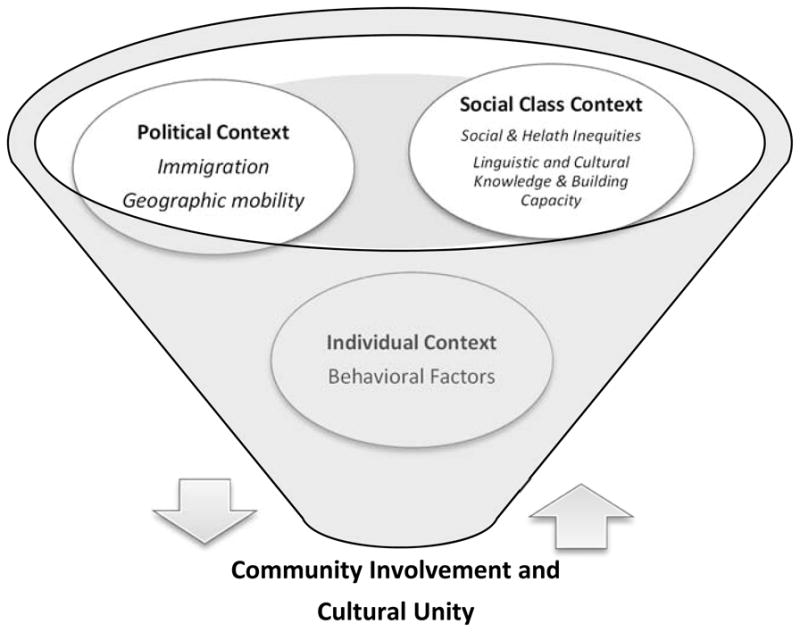

Following the CSDH main concepts framework, categories were arranged in three different contexts: 1) Political Context: Immigration Problems and Geographic Mobility 2) Social Class Context: Social and Health Inequities and Lack of Linguistic and Cultural Knowledge & Building Capacity 3) Individual Context: Behavioral Factors. In addition, Community Involvement and Cultural Unity emerged as independent categories that were considered crosscutting determinants of well-being; FBO leaders revealed a hope that these factors could help reduce the psycho-social inequities and vulnerabilities that many Latinos face in rural environments.

All categories are presented below (See Figure 1), along with interview excerpts that clarify their meaning; an English idiomatic translation, which is faithful to the original meaning, is presented here.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the Categories Identified

Political Context

Immigration problems

FBO leaders conveyed concerns about the implications of the undocumented status of many Latinos in the community, such as the lack of legal documents and fear of the migratory laws. They were also concerned about immigrants experiencing discrimination because of their physical appearance in rural areas where residents are predominantly non-Hispanic/White. Rural Latinos are a visible minority and a visibly excluded population; as a result, being an immigrant entails living in continuous fear, which impacts their families and their children’s well-being.

“We are extremely concerned about the anti-immigration law that many states are approving…these are generating constant panic…in the community among the adults and as a consequence among the children.” “Children are always afraid that their parents….will be deported”. “The new immigration law is making Latinos more scared than ever…they are scared because their faces, hair…tell they are Latinos.” “We hope in the future there is an immigration law that can help the undocumented…working people.” “Latinos face discrimination, problems of immigration, and persecution….”

Geographic Mobility

FBO leaders frequently mentioned the lack of public or private transportation and rural geographic isolation as problems within the Latino community. In rural counties, Latinos are physically and socially isolated even from their ethnic counterparts, which can compromise their emotional well-being. “Latino people don’t have transportation…and they cannot drive because they don’t have drivers’ licenses.” “They are really isolated in their own little world.”

Social Class Context

Social & Health Inequities

FBO leaders listed the many social factors and health inequities affecting rural Latinos—racism, exploitation in the work environment, dearth of continuing education, lack of health services information/resources, and absence of cultural communication exchange between communities. Rural Latinos are constantly exposed to these stressors, which are worse in rural areas.

“In the Latino community, we have lots of problem such as lack of formal education and not enough jobs for them…many [Latinos] work very hard and gain very, very… little.”

“Sometimes [they suffer from] alcoholism and drug addiction and they don’t have access to health care.” “We don’t have services to visit their [Latinos] homes, support groups available, and we don’t have child care service for… [Latinos] that speak only Spanish.”

Lack of Linguistic and Cultural Knowledge & Building Capacity

FBO leaders frequently mentioned the linguistic challenges Latino immigrants face and more specifically, how these challenges can compromise the capacity of individuals to enhance their personal networks and professional skills as well as their own status in the rural community. Rural Latino immigrants have fewer chances to learn and communicate in English, which was seen as an essential step to becoming acculturated and promoting co-learning, capacity-building, and trusting relationships. Mastery of English was also central to feeling that they belong where they live. One of the FBO leaders expressed:

“I hope Latinos could start learning English…so they can speak the language anywhere and really FEEL part of the community. English classes are not easily available in this community... I hope we could sow the seed (sembrar semillas) between the people [Latinos], so they can get better standard of living encouraging the youth and the children to study more. Many parents cannot help their kids in school due to the lack of English knowledge…”

Individual Context

Behavioral Factors

FBO leaders also discussed health-damaging behaviors, and indicated they may be a result of Latino exposure to social determinants common in rural areas. According to the FBOs, some immigrants refuse to learn a new language, engage in acts of familial irresponsibility (e.g. extramarital relationships), and demonstrate lack of motivation for life commitment or improvement, which may hinder the sense of Latino community. “Some Latinos are not really committed to invest in their families and in their own lives.” “Some of them [Latinos] don’t want to learn a new language; they are not responsible with their family… [they have a] macho men mentality, and they don’t have motivation to improve their life.”

Crosscutting Determinants

Community Involvement

Overall, FBO leaders stated that well-being is determined by social, religious, and personal factors and that religion is already a strong component in the Latino community. However, the absence of community connection and social networking are major problems for Latinos living in rural areas. In addition, Latinos experience hardships that can prevent the development of community relationships and feelings of belonging.

“Mexicans are very religious, but attending to Sunday Mass may be difficult for them, since their employers are insensitive to their Sunday obligation…they are very hard workers and dedicated to family…but they are isolated, they don’t have friends…they don’t have a sense of belonging to this community”.

Cultural Unity

FBO leaders remarked on how sense of belonging to a church could unify the Latino communities and connect them with the rural mainstream cultural communities. “We are all brothers and sisters in Christ…” and “I hope that everybody [Latinos and non-Latinos] can be together without prejudice, discrimination no matter what race the person is.”

DISCUSSION

FBO leaders have insight into the psycho-social contexts of rural Latinos, and were able to identify significant adverse determinants of well-being within political, social, and individual contexts. Determinants in the political context, such as immigration problems and geographic mobility, are associated with those of the social context, such as social and health inequities, lack of linguistic and cultural knowledge, and building capacity. These categories, which seem to be the root of well-being inequities in rural Latinos, are closely related to the well-recognized social determinants of mental health promotion such as social inclusion, community building, social support, discrimination prevention, and adult literacy programs (Christodoulou et al., 2011). In addition, the FBOs statement that Latinos do not feel they belong to rural areas is significant because a lack of belonging can have serious, negative effects on mental well-being. Indeed, FBO leaders were concerned about the effects of adverse social determinants on the lives of individuals, families, and adolescents.

Although most of the identified adverse socio-determinants are recurrent in the emergent Latino literature (Passel & Cohn, 2011; Shihadeh & Barranco, 2010; Shihadeh & Winters, 2010; Stacciarini, et al., 2014), this study revealed the need to build community networking in rural Latinos. In fact, research has shown that Latinos in rural areas experience significant social isolation (Stacciarini, et al., 2014; Stacciarini et. al., 2015), are highly segregated from non-Latinos (Lichter, et al., 2010) and are viewed with suspicion by the established Latino community (Leach & Bean, 2008). FBO leaders confirmed the results of this research and indicated that Latinos in new destinations lack the social resources and connections of traditional locations (Shihadeh & Winters, 2010). Thus, FBO leaders’ suggested that an increase in social capital and community engagement may decrease inequalities related to race/ethnicity, income, gender, and geographic location (Valencia-Garcia, Simoni, Alegria, & Takeuchi, 2012).

FBOs expressed significant hope for Community Involvement and Cultural Unity and changes in Individuals with statements such as, “God will find a way to solve the most challenging community problems.” This passive, faithful approach to problem solving may indicate that FBOs need help strategizing ways to address the psychosocial needs of the rural, Latino community. This may be a great opportunity for mental health nurses and FBOs to collaborate on interventions to promote well-being in the rural Latino immigrant communities.

Findings add support for the development of interventions that focus on the promotion of mental health through the reduction of social health-determinants. In this underserved communities, mental health nurses need to use novel psychosocial approaches to minimize the social determinants that impact well-being and refrain from using interventions that approach community problems from an illness perspective. In fact, successful interventions have targeted SHDs to enhance residents’ access to social and economic resources and use existing social capital to enhance community well-being (Brennan, et al., 2008; Farquhar et al., 2008). A well-recognized community-based intervention developed by Barreto (2010) distinguishes between sufrimiento (suffering, mostly due to social inequities) and enfermedad (disease). Those who are mentally ill (e.g. depressed) are referred to the health care system and treated with evidence-based therapeutics, and those who are suffering (e.g. sad), receive community and culturally-based interventions from a variety of traditions, including religious customs (Barreto, 2010).

Nurses are on the frontline to respond to concerns highlighted by FBO leaders, and have the expertise to develop culturally competent psychosocial interventions to foster social inclusion and community engagement. Nurse-led interventions should be developed in conjunction with FBO leaders, and should respect local culture and community resources. For example, nurses may help build a soccer alliance that brings community members together to play soccer before or after social support meetings. These gatherings could be a powerful way to enhance feelings of social inclusion and belonging, develop ethnic identity, and promote emotional well-being. Similarly, nurses may lead the training of community health workers to engage rural Latinos in activities that enhance social belonging, promote mental health, and reduce social/health disparities. Training community health workers is important because, to date, they have been largely overlooked as facilitators/educators in mental health promotion interventions (Waitzkin, et al, 2011, Getrich, Heying, Willging & Waitzkin, 2007), particularly in emerging immigrant Latino communities (Tran, et. al, 2014), where services may be nonexistent. Studies using community health workers to implement popular education programs (e.g. girl’s leadership group, homework club, environmental health project) demonstrated significant improvement in social support, well-being, and mental health in an underprivileged community of African Americans and Latinos in Portland, Oregon (Farquhar, Michael, Wiggins, 2005; Michael, Farquhar, Wiggins,& Green, 2008). Thus, mental health nurses in rural areas are well-recognized as community leaders, and are the ideal professional to train community health workers in similar programs that aim to improve the psycho-social contexts and mental well-being of Latinos.

The data described here have some limitations: (a) Although FBO leaders were from five different churches, not all religions are represented. In addition, religions may differ in how they perceive the needs of Latino immigrants, and the role of religion in Latino communities is potentially complex (Shihadeh & Winters, 2010); (b) the sample size was small and limited to two small neighboring rural counties in FL. Although these limitations should be considered, they do not override the benefits that can be gained from integrating FBOs perceptions with academic research and service approaches. In fact, safe social networks need to be developed by nurses to inform and improve rural mental health promotion programs and policies. Nurse researchers who work in partnership with FBOs may help enhance social networks, community connectedness, and social capital in rural Latino communities. Indeed, researchers agree that the synthesis of community experts, knowledge of local culture, and expertise of academic health professionals, may foster social changes and develop interventions that reduce psycho-social health inequities in underserved populations (Freire, 1972, 1982; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Stacciarini et al., 2011; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010).

Contributor Information

DR. JEANNE-MARIE R STACCIARINI, Email: JEANNEMS@UFL.EDU, COLLEGE OF NURSING - UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, ENV, 101 S. NEWEL DRIVE, GAINESVILLE, 32611 UNITED STATES.

DR. RAFFAELE VACCA, Email: R.VACCA@UFL.EDU, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, COLLEGE OF NURSING, GAINESVILLE, UNITED STATES

DR. BRENDA WIENS, Email: WIENS@PHHP.UFL.EDU, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL AND HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY COLLEGE OF PUBLIC HEALTH AND HEALTH PROFESSIONS, GAINESVILLE, UNITED STATES

MISS. EMILY LOE, Email: ELOE591@GMAIL.COM, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, COLLEGE OF NURSING, GAINESVILLE, UNITED STATES

MRS. MELODY LAFLAM, Email: MELODY_LAFLAM@MBHCI.ORG, MERIDIAN BEHAVIORAL HEALTHCARE, INC., BRONSON, UNITED STATES

MRS. AWILDA PÉREZ, Email: AWILDAPEREZ08@HOTMAIL.COM, HOLY FAMILY CATHOLIC CHURCH, WILLISTON, UNITED STATES

MRS. BARBARA LOCKE, Email: BARBARA.LOCKE@FLHEALTH.GOV, PUBLIC HEALTH DEPARTMENT, LEVY COUNTY, BRONSON, UNITED STATES

References

- Barreto AP, editor. Terapia comunitária: passo a passo. 4. Fortaleza, Brasil: Fortaleza Gráfica; 2010. [Community Therapy – step by step] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan RLK, Baker EA, Metzler M. Promoting health equity: A resource to help communities address social determinants of health. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou G, Jenkins R, Tsipas V, Christodoulou N, Lecic-Tosevski D, Mezzich J. Mental health promotion: A conceptual review and guidance. European Psychiatric Review. 2011;4(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cook B, Alegría M, Lin JY, Guo J. Pathways and correlates connecting Latinos’ mental health with exposure to the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSDH; F. R. o. t. C. o. S. D. o. Health, editor. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030–1036. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar A, Wiggins N, Michael Y, Luhr G, Jordan J, Lopez A. “Sitting in different chairs:” Roles of the community health workers in the Poder es Salud/Power for Health project. Education for Health. 2008;21(2):39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P, editor. Pedogogy of the Oppressed. Penguim: Harmonds-Worth; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P, editor. Creating alternative research methods: Learning to do it by doing it. New Delhi: Society for Participatory Research in Asia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Getrich C, Heying S, Willging C, Waitzkin H. An ethnography of clinic “noise” in a community-based, promotora-centered mental health intervention. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(2):319–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarratano G, Bustamante-Forest R, Carter C. A multicultural and multilingual outreach program for cervical and breast cancer screening. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(3):395–402. doi: 10.1177/0884217505276059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari N, Davis M, Heisler M. Strangers in a strange land: Health care experiences for recent Latino immigrants in Midwest Communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19:1350–1367. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2020. July 7 2015 Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health. [Google Scholar]

- Hiott AE, Grzywacz J, Davis S, Quandt S, Arcury T. Migrant farmworker stress: Mental health implications. Journal of Rural Health. 2008;24(1):32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00134.x. 1748-0361.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach MA, Bean FD. The structure and dynamics of Mexican migration to new destinations in the United States. In: Massey DS, editor. New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008. pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Domenico P, Michael T, Stephen MG. Residential segregation in new Hispanic destinations: Cities, suburbs, and rural communities compared. Social Science Research. 2010;38:215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Michael YL, Farquhar SA, Wiggins N, Green MK. Findings from a community-based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2008;10(3):281–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman M, editors. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2. SAGE Publications, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn DV. Unauthorized Immigrant Population: National and State Trends, 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center; Pew Hispanic Center and Pew Forum on religion and public life, editor Changing faiths: Latinos and the transformation of American religion. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rose DR. Social disorganization and parochial control: Religious institutions and their Communities. Sociological Forum. 2000;15(2):339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard RH. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(85):85–109. doi: 10.1177/1525822X02239569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz R. A profile of Latinos in rural America. 2008 Retrieved July 31, 2008, from http://www.carseyinstitute.unh.edu/documents/SaenzRuralLatinoFS08.pdf.

- Shihadeh ES, Barranco RE. Latino immigration, economic deprivation, and violence: Regional differences in the effect of linguistic isolation. Homicide Studies. 2010;XX(X):1–20. doi: 10.1177/1088767910371190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh ES, Winters L. Church, place, and crime: Latinos and homicide in new destinations. Sociological Inquiry. 2010;80(4):628–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682x.2010.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacciarini JMR, Wiens B, Coady M, Schwait AB, Perez A, Locke B, … Bernardi K. CBPR: building partnerships with latinos in a rural area for a wellness approach to mental health. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(8):486–492. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.576326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacciarini JMR, Rosa AC, Ortiz M, Munari DB, Uicab G, Balam M. Promotoras in Mental Health: A Review of English, Spanish, and Portuguese Literature. Family & Community Health. 2012;35(2 Special CHW Issue):92–102. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182464f65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacciarini JMR, Smith RF, Wiens B, Pérez A, Locke B, Laflam M. I didn’t ask to come to this country…I was a child: The mental health implications of growing up undocumented. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0063-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacciarini JMR, Smith R, Garvan CW, Wiens B, Cottler LB. Rural Latinos’ mental wellbeing: A mixed-methods pilot study of family, environment and social isolation factors. Community Mental Health Journal. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal MJ, Williams DR, Musick MA, Buck AC. Religious practices, beliefs, and mental health: variations across ethnicity. Ethnical Health. 2012;17(1–2):171–185. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.655264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AN, et al. Results From a Pilot Promotora Program to Reduce Depression and Stress Among Immigrant Latinas. Health Promotion Practice 2014. 2014;15(3):365–372. doi: 10.1177/1524839913511635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas A. Mexicans immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source. 2014 Jul 9; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states-0#5.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanics in the United States. 2012 Retrieved March 25, 2014, from http://www.census.gov/population/hispanic/data/2012.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. State & County Quick Facts. 2010 Retreived March 25, 2015, from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/12/12075.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. 2. Washington, DC: 2011. Principles of Community Engagement; pp. 1–193. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Garcia D, Simoni JM, Alegria M, Takeuchi DT. Social capital, acculturation, mental health, and perceived access to services among Mexican American women. Journal of Consultation Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(2):177–185. doi: 10.1037/a0027207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives General Psychiatry. 1998;55(9):771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H, et al. Promotoras as mental health practitioners in primary care: A multi-method study of an intervention to address contextual sources of depression. Journal of Community Health. 2011;36(2):316–31. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9313-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran BD. Community-Based Participatory Research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]