Abstract

Background/Objectives

Disabled older adults often rely on an informal network of family members to provide care and assist with health care decisions, however many family caregivers are being left out of critical patient-clinician discussions, including discussions about life expectancy.

Design

Qualitative interview study.

Setting

Caregivers were recruited from Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), caregiver support groups, and an advertisement through a nationwide caregiver advocacy group website.

Participants

Caregivers, both active and bereaved, whose primary language was either English or Cantonese, having provided care within the last 5 years to a disabled adult age 65 or older. Forty-two caregivers were interviewed, 79% female, 60% white, with an average age of 54 years.

Measurements

Semi-structured, telephone interviews were conducted with caregivers who were asked about experiences and preferences related to clinician communication about life expectancy, including preferences and attitudes toward being included in discussions about life expectancy, how such information should be delivered, and how concerns about uncertainty and hope should be addressed by clinicians. Responses were analyzed qualitatively using constant comparison until thematic saturation was reached.

Results

A fourth (26%) of caregivers had been involved in a conversation with a clinician about patient life expectancy, even though a substantial majority (79%) expressed a preference to have such a discussion. According to caregivers, clinician concerns about taking away patient hope or the uncertainty of prognostic information should not deter them from bringing up the topic of life expectancy. Thematic analysis suggested several approaches may facilitate prognosis communication, including: establishing a relationship with the caregiver and care recipient; delivering the prognosis in clear, plain language; and responding to emotion with empathy.

Conclusion

Caregivers reported a preference for being included in conversations about a care recipient's life expectancy.

Keywords: Informal caregivers, Communication, Prognosis, Life expectancy, Uncertainty, Hope, Elders and older adults

Introduction

As disabled elders advance in age and disability, they often rely on an informal network of family members to provide care and assist with health care decisions. In fact, family caregivers provide the majority of the hands-on care to disabled older adults living in the US.1 In 2009, a national survey of caregivers estimated that 43.5 million Americans provide unpaid care to an older adult (50+)2 and the uncompensated hours of informal care in the US at that time had a total estimated value of $450 billion.3

Although these caregivers are integral to ensuring the safety, comfort and well-being of elderly care recipients, many family caregivers are being left out of critical patient-clinician discussions, such as discussions about prognosis or life expectancy.4,5 By excluding these key members of the healthcare team from prognosis conversations, family members may be unable to make needed preparations (e.g., financial, social, emotional) or lack sufficient context to inform surrogate decision-making.6,7 Research has shown that patients frequently want family members included in conversations relating to prognosis, disease progression and advance care planning.8,9 Moreover, research has shown that end-of-life discussions between clinicians and patients can result in less aggressive care and increased hospice use, which in turn results in better bereavement outcomes for caregivers including lower risk for developing a major depressive disorder, lower incidence of experiencing regret, and feeling more prepared for the patient's death.10

More recently, we have advocated for discussing prognosis with care recipients with years left to live, much farther “upstream” from the days to months timeframe that typifies hospice or end-of-life conversations.11 This recommendation is based on the finding that many tests and treatments in disabled older adults hinge critically on patient prognosis. The American Geriatrics Society's Choosing Wisely recommendations for cancer screening and hemoglobin A1C targets for older adults with diabetes hinge on patient prognosis.12,13 Clinicians, however, report having concerns about whether, when and how to communicate prognosis to patients11,14-16 and little is known about how clinicians feel about including family members in discussions about patient prognosis.

Previous work suggests many patients generally want to be told about their life expectancy.9,17 Other studies have looked at the preferences of caregivers for frail older adults for receiving information in general.18 To our knowledge, however, outside of the intensive care unit setting,19 no studies have explored the experiences and preferences of family caregivers of disabled older adults related to being included in discussions about life expectancy. These perspectives are especially relevant because medical decisions are often made collaboratively among relatives, or deferred to a primary caregiver.3 The crucial role of caregivers in conversations about care recipient prognosis, therefore, deserves greater attention. To respond to the need for a greater understanding of caregiver preferences and attitudes toward being included in discussions about life expectancy, we conducted in-depth interviews with family caregivers. We examined the reasons behind their stated attitudes and preferences and included probes about how such information should be delivered and how concerns about uncertainty and hope should be addressed by clinicians.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

We conducted a qualitative study using telephone interviews with family caregivers who were purposively recruited from a broad cross-section of regional and national sites, including a Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), caregiver resource centers, senior centers, two VA medical centers, and a geriatric clinic (all in the Western US using research flyers and phone-based referrals), as well as an advertisement through a nationwide caregiver advocacy group website. Recruitment was designed to ensure diverse caregiver experiences and perspectives. To be eligible for participation, caregivers could be actively providing care, or bereaved but having had provided care within the last 5 years to a disabled adult age 65 or older. Disability was defined as needing assistance with at least one activity of daily living. Using these procedures, we interviewed 42 caregivers. Eligible participants were adults whose primary language was either English or Cantonese and could participate in a 45-minute phone interview. Since participants were recruited using study flyers and other advertisements, there were no refusals to participate at the point of contact. However, four potential candidates were deemed ineligible. In two cases, the care-recipient did not meet our definition of disabled; in one case the patient was <65 years old; and in one case the care recipient had died >5 years prior.

We began interviewing by seeking a variety of caregivers among ethnic groups, caregiving status (bereaved or not) and proximity to the care recipient. We conducted and recorded semi-structured qualitative interviews by phone. After translation from English into Cantonese, the interview guide was reverse-translated to ensure accuracy. Where words or concepts did not translate well from English to Cantonese, we located a word or concept that worked well in Cantonese and translated back to English.

Cantonese interviews were conducted by an experienced interviewer who spoke both fluent English and Cantonese and had performed Chinese-language interviews for three previously published studies.17,20,21 The Cantonese interviewer also transcribed audio-recorded Cantonese interviews into English for coding and analysis by the research team. All interviewers received small group instruction on qualitative interviewing techniques and were given feedback on initial transcription efforts.

The interview guide was revised throughout data collection to explore emerging themes. All interviews took place over a 6-month period in 2012. Caregivers were compensated $25 for their time. The Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Research and Development committee approved this study and its procedures.

Data Collection

Caregivers were asked about experiences and preferences related to clinician communication about life expectancy. We focused on responses to the following four interview prompts:

Has a doctor ever talked to you about how long [the care recipient] might have to live? If so, can you tell me that story?

In your opinion, who should be told about how long a patient might have to live? The patient only? The family only? Both patient and family? Together or separate?

Some doctors are afraid to discuss how long patients might have to live because the information is not certain. What do you think about this?

Some doctors are afraid to discuss how long patients might have to live because they are concerned it may take away hope. What are your thoughts about this?

Table 1 provides a more detailed selection of the interview prompts used for data collection.

Table 1. Selected Questions and Prompts from the Interview Script*.

|

The selected interview prompts and questions presented here are from the “active caregiver” version of the interview script. A modified version of the script was used for bereaved caregivers. Interview content, not shown here, also included questions about: a.) the caregiving experience and role; b.) culture, race, and ethnicity; c.) quality of life for care recipient and caregiver; and, d.) basic demographics.

Analysis

Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed for thematic content. When interviews were conducted in Cantonese, responses were first translated into English prior to analysis. An inductive and systematic process was used to identify recurrent and emergent themes within these data. Caregiver responses to open-ended questions and probes were analyzed for thematic content using the general tenets of the constant-comparative method.22-24 Raw data were unitized using open (axial) coding. Coded excerpts with similar themes were grouped together. After the initial round of coding, clustering, and categorization, these findings were reviewed by Drs. Cagle and Smith, for corroboration and peer oversight. The research team also analyzed interview content for cultural similarities and differences.

The research team included representatives from medicine, social work, and public health. A subsample of transcripts (N=10, 24%) were reviewed and independently coded by at least two members of the research team with >80% concordance. Based on this preliminary review of interview transcripts, the team resolved any contrary or conflicting themes and established an initial codebook. Team members also met on a regular basis to make decisions about any transcript excerpts in which the coding was unclear. This process was repeated in an iterative fashion until thematic saturation was reached.25 Study recruitment concluded once data saturation was achieved. Saturation was determined by team consensus when interviews were no longer eliciting new themes regarding preferences related to communication about prognostic information. All data were entered into a secure database. NVivo 8 software (QSR International), Microsoft Excel and Word were used for data analysis. Direct quotes that encapsulated identified themes are presented as exemplars; all identifying content was changed or removed to preserve respondent anonymity.

Results

As shown in Table 2, the sample was largely female (79%), with an average age of 54 years. Sixty percent of caregivers were white, 26% Asian, 5% Latino, and 5% African American. Most participants were active caregivers (79%) while the remaining 21% were bereaved. Two-thirds of the sample (67%) were adult children providing care to an elderly parent; and most either co-resided with (41%) or lived near (36%; <1 hour away) the care recipient. Care recipients were majority female (60%) and predominantly 80+ years of age. The most common primary condition requiring care was dementia or other memory-related condition (50%) and exactly half had multiple conditions requiring care.

Table 2. Sample Characteristics - Caregiver Respondents (N=42).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Caregiver Characteristics | |

| Age M(±SD) | 54.4 (12) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (21.4%) |

| Female | 33 (78.6%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| African American | 2 (4.8%) |

| Asian/Pacific-Islander | 11 (26.2%) |

| Caucasian | 25 (59.5%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 2 (4.8%) |

| Other | 2 (4.8%) |

| Years of Education | |

| <12 | 2 (4.8%) |

| 12-16 | 27 (64.3%) |

| >16 | 13 (31%) |

| Caregiver Status | |

| Active Caregiver | 33 (78.6%) |

| Bereaved Caregiver | 9 (21.4%) |

| US Census Region | |

| West | 21 (50%) |

| Midwest | 4 (9.5%) |

| Northeast | 4 (9.5%) |

| South | 5 (11.9%) |

| Relationship to Patient | |

| Spouse/Partner | 7 (16.7%) |

| Child | 28 (66.7%) |

| Other Relative | 4 (9.5%) |

| Friend | 1 (2.4%) |

| Other | 2 (4.8%) |

| Caregiver Proximitya | |

| Co-residing | 17 (40.5%) |

| Proximate (<1 hour away) | 15 (35.7%) |

| Long-distance (≥1 hour away) | 5 (11.9%) |

| Transitional | 4 (9.5%) |

| Care Recipient Characteristicsb | |

| Age | |

| 60-69 | 4 (9.5%) |

| 70-79 | 8 (19%) |

| 80-89 | 13 (31%) |

| 90+ | 16 (38.1%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 17 (40.5%) |

| Female | 25 (59.5%) |

| Nursing Home Admissionc | |

| Yes | 11 (26.2%) |

| No | 31 (73.8%) |

| Primary Diagnosis | |

| Dementia/Memory-related | 21 (50%) |

| Heart Disease/Stroke | 13 (31%) |

| Frailty/Non-specific Decline | 12 (28.6%) |

| Hip Fracture | 4 (9.5%) |

| Diabetes | 3 (7.1%) |

| Lung Disease/COPD | 2 (4.8%) |

| Other | 5 (11.9 %) |

| Multiple conditions that require(d) care? | |

| Yes | 21 (50%) |

| No | 21 (50%) |

Co-residing=caregivers who lived with the care recipient; Proximate=caregivers who lived <1 hour away; Long-distance=caregivers who lived ≥1 hour away; Transitional=caregivers who reported moving in with the care recipient on a temporary basis.

In two cases caregivers were caring for both parents at the same time – a mother and father. In these cases, we elected to report the characteristics of the parent requiring the majority of care. In 6 cases the exact age of the care recipient was unknown and therefore estimated based on information about the age of the spouse or adult child. Information on care recipient's primary diagnosis and multiple conditions were based on caregiver report.

Nursing home admission could have occurred at any point during the care recipient's care.

Caregiver Involvement in Conversations about Life Expectancy

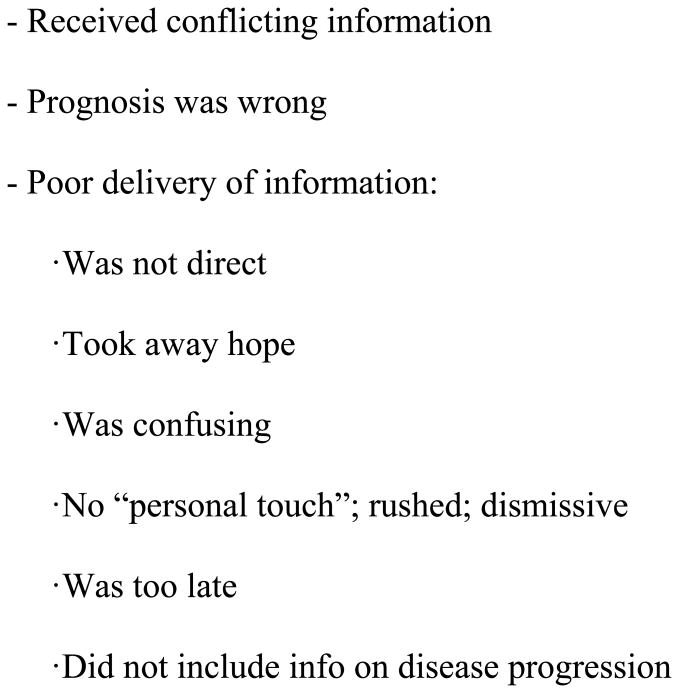

In 11 cases (26%), caregivers reported they had been included in a conversation with a clinician about life expectancy, including only 3 of the 9 bereaved caregivers. Among caregivers who had been involved in a discussion with the doctor about the care recipient's life expectancy, they described the conversation and aspects of the discussion that they liked (positive aspects) as well as what they disliked (negative aspects). Figure 1 summarizes themes identified in response to questions about being included in conversations about patient life expectancy. Caregivers generally reported positive experiences when the doctor presented information about life expectancy clearly and directly, including the use of numerical estimates. Caregivers also linked positive experiences to the clinician having had a prior relationship with the family. Caregivers reported negative experiences when doctors were perceived as being rushed, dismissive or lacking “a personal touch” or a “good bedside manner.” In general, caregivers emphasized the importance of providing clear, accurate and timely communication about life expectancy – and that such communication information should be accompanied by information about the expected disease progression and potential care needs.

Figure 1. Caregiver Experiences of Being Included in Discussions with a Clinician about Life Expectancy.

The remaining three-fourths of caregivers indicated that they had not been involved in a conversation with the patient's doctor about life expectancy. In some of these cases, caregivers had been included in discussions about the care recipient's mortality, disease progression or risks of surgery. But these conversations did not include a timeframe, whether general or specific, related to the care recipient's projected mortality. For example, one caregiver recalled that the doctor had told her that the patient's “brain was getting old” and “had lived beyond its time” and “eventually it's going to die.” However, a life expectancy estimate was not provided during the discussion.

Caregiver Preferences for Discussing Life Expectancy

In our sample, the majority of caregivers (n=18, 43%) said, that when discussions of life expectancy occur, the doctor should tell the patient and family together. As one caregiver shared, that way “everybody hears the same thing,” “is on the same page” and they can “prepare as a family.” Just under a fifth (n=8, 19%) stated that clinicians should tell the family first and then let the family determine whether, and how, to relay that information to the care recipient. Overall, 79% of caregivers (n=33) were adamant that family members should be included in the conversation, while the remaining caregivers were either unclear about their preferences (n=6, 14%) or stated that their answer would vary depending on the situation (n=3, 7%).

One family caregiver who strongly endorsed including family members in conversations about life expectancy remarked:

If you don't know, all of a sudden they're gone then you have all these regrets. ‘I didn't say this.’ ‘I didn't do this.’ ‘I didn't take that last picture.’ ‘I didn't say, I love you that one more time.’

[Partner, 48 years old, active caregiver]

Another caregiver responded:

Doctors have to let people know what they know so that the people who are ill or their families can make the decisions. It's not for the doctors to make the decisions about how one decides what they want their end-of-life experience to be.

[Daughter, 53 years old, active caregiver]

None of the interviewees expressly indicated that family members should be excluded from conversations about life expectancy – or that the patient should be told first.

Regardless of whether a discussion of life expectancy had occurred, we asked all caregivers to comment on how such a conversation should ideally take place, including factors clinicians should consider when engaging patients and caregivers in these discussions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Caregiver Preferences and Suggestions regarding Discussions with a Clinician about Life Expectancy (n=42).

Caregiver Suggestions for Dealing with Uncertainty

Many caregiver respondents suggested that information about life expectancy should be communicated even if uncertain, but that the information should be qualified accordingly. It appears, therefore, that it is important for clinicians to be upfront with families about how accurate, or inaccurate, the estimates of life expectancy are.

As one caregiver put it:

Life is uncertain. I think [doctors] need to prep us: “Of course, we can't predict the future but it's our opinion that you have such-and-such time to live based on your physical condition.” So I think it's alright to talk about it, but they need to say, “Of course, we're not certain about this.” Who is certain about it?

[Spouse, 79 years old, active caregiver]

In most cases, caregivers suggested that as long as the limitations and unknown factors are clearly communicated, a reasonable degree of uncertainty was allowable and even expected. According to some caregivers, projections of life expectancy should avoid definitive terms (e.g., by giving a range).

Caregiver Suggestions for Preserving Hope

Caregivers acknowledged the potential of prognosis conversations to take away hope, and offered a number of suggestions to clinicians about how to approach these conversations. When asked whether discussing life expectancy would take away hope, one caregiver remarked that regardless of the potential to take away hope, she would want to know:

Taking away hope? I don't understand that argument. It's like saying, ‘I'm not going to tell you that your roof has a big hole in it because I know you're hoping that it doesn't.’ […] I don't think this is a hope or no hope situation – it's an information situation. I would want to know.

[Daughter, 68 years old, active caregiver]

Another caregiver suggested that clinicians adopt a practical approach to communicating information about life expectancy by highlighting objective clinical data and relying on observable signs of physical and/or cognitive decline witnessed by the patient and family. Some caregivers suggested that hope can be preserved by strengthening coping resources and preserving a sense of control by focusing on modifiable factors. For example, clinicians can reassure families that some level of independence can be maintained with the use of assistive devices such as canes, walkers or wheelchairs.

Another caregiver highlighted the importance of supporting the care recipient's/family's spiritual beliefs to maintain a sense of hope:

Often that spiritual aspect can be the one point that will make or break a person. When someone has a disease that is chronic and life-threatening it can be their spiritual beliefs that give them the strength to carry on, to have hope, to enjoy the days that they have.

[Partner, 48 years old, active caregiver]

In terms of preferences and experiences related to prognostic communication, we generally observed more similarities across cultural groups than differences. This being said, for non-English-speaking individuals, language was a noteworthy barrier to prognostic communication. Additionally, one Cantonese-speaking caregiver remarked that in Chinese culture, “death is not up for discussion.”

Discussion

Only a fourth (26%) of caregivers in our sample had been involved in a conversation with the clinician about patient life expectancy, even though a substantial majority (79%) expressed a preference to have such a discussion – and none were completely averse to being included in the conversation. Findings suggest that information about prognosis and life expectancy is supportive of caregivers' needs to plan their own lives. According to caregivers, clinician concerns about taking away patient hope or the questionable accuracy of prognostic information (i.e., uncertainty) should not deter them from bringing up the topic of life expectancy. Qualified information that also includes expectations about disease trajectory, care needs and ways to preserve independence, coupled with clinician empathy, may facilitate the exchange and receptivity of such difficult communication.

Our findings build on previous studies that have shown that care recipients want family members included in conversations relating to prognosis in end of life settings.8,9 Our study builds on these findings by examining the experiences and preferences of the caregiver in discussions that include patient life expectancy estimates on the order of years, long before the end of life time period. Other studies have reported that clinicians have concerns about communicating prognosis to patients,11,14-16 and little is known about how clinicians feel about including family members in discussions about prognosis. Furthermore, caregivers in our study provided suggestions for how these conversations should ideally take place, and provided insight into how topics like uncertainty and the loss of hope should be addressed by clinicians.

One unique aspect of our study is the inclusion of Asian/Pacific Islander caregivers (26% of the sample), an understudied group. Although our methods did not allow for a comprehensive examination of differences by culture, we anecdotally observed general similarities across groups. Discussions of prognosis, however, may be difficult to initiate with some Chinese-speaking individuals either due to language barrier or culture taboos about discussing death. This latter point echoes what previous researchers have observed among older Asian groups in other studies – that death is often considered a taboo subject and may be linked to fatalistic beliefs (i.e., that discussions about death could contribute to ill-health or untimely demise).26,27 However, further research is needed to better understand the impact of culture on discussions about life expectancy.

Results should be considered within the context of the study's limitations. Due to our sampling methodology, findings cannot be generalized to the larger population of all caregivers. Furthermore, based on our recruitment methods, we were unable to estimate the impact of selection bias and non-participation. Since we relied on interested study candidates to contact our research team in response to study advertisements, caregivers who were feeling overwhelmed, for example, may have elected not to contact our research team. Although we provide novel data about caregiver preferences, our findings are only the first step in uncovering the experiences and preferences of family inclusion in conversations where prognosis is being discussed. It is also important to acknowledge the meaning and importance of prognostic information may vary based on the type of relationship with the care recipient, or whether the respondent was an active caregiver or bereaved. Future research should examine the relative importance of such information across different groups of caregivers.

In conclusion, in our study prognostic information was found to be important to caregivers of disabled elders. This information may be useful for caregivers even when a care recipient has years to decades left to live because discussions about life expectancy may inform decisions about preventative tests and treatments, such as cancer screening or blood sugar control in diabetes.12,13 Future research is needed to examine the prevalence of prognostic discussions with caregivers. More study is also required to explore whether physicians are excluding caregivers from discussions of prognosis and life expectancy, or whether they are neglecting to have these conversations at all.

Based on our data, we suggest the following approach to the issue of prognosis discussions with disabled elderly care recipient and caregivers. First, Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations allow caregivers to be involved in medical discussions as long as the patient agrees. Clinicians should offer to discuss prognosis with patients, and ask about preferences for discussing prognostic information with caregivers. Second, if family members are not present during a clinical encounter where life expectancy is discussed, clinicians should inquire about patient preferences for communicating the pertinent information with caregivers or other members of the patient's informal support network. Third, caregivers in our study offer a number of suggestions for how to ideally approach such conversations, including establishing a relationship with the patient and caregiver, delivering the prognosis in clear, plain language, and responding to emotion with empathy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jackie Parker, MSW for her assistance with preparing this manuscript.

Funding Sources: Dr. Cagle's efforts were supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), 5T32AG000212 and a Junior Faculty Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center. Dr. Smith was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K23 040772) and the American Federation for Aging Research

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Authors' Contributions: Study concept and design: Alexander K. Smith S, John G. Cagle

Acquisition of data: Julie N. Thai

Analysis and interpretation of data: John G. Cagle, Keelan M. McClymont, JNT, Alexander K. Smith S

Preparation of manuscript: John G. Cagle, Keelan M. McClymont, Julie N. Thai, Alexander K. Smith

Sponsor's Role: Sponsor had no role in the design, methods, data collections, analysis or preparation of paper.

References

- 1.Doty P. The evolving balance of formal and informal, institutional and non-institutional long-term care for older Americans: A thirty-year perspective. Pub Policy Aging Rep. 2010;20:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and AARP. Caregiving in the U.S. Funded by MetLife Foundation. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, et al. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update: The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: Perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1398–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG, et al. Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: When do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1176–1185. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russ AJ, Kaufman SR. Family perceptions of prognosis, silence, and the “suddenness” of death. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2005;29:103–123. doi: 10.1007/s11013-005-4625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. Supporting family caregivers at the end of life: They don't know what they don't know. JAMA. 2004;291:483–491. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. When and how to initiate discussion about prognosis and end-of-life issues with terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: Patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AK, Williams BA, Lo B. Discussing overall prognosis with the very elderly. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2149–2151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Workgroup AGSCW. American Geriatrics Society identifies five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:622–631. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Workgroup AGSCW. American Geriatrics Society identifies another five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:950–960. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. Attitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2389–2395. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.21.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1096–1105. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:507–517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahalt C, Walter LC, Yourman L, et al. “Knowing is better”: Preferences of diverse older adults for discussing prognosis. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:568–575. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1933-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robben S, van Kempen J, Heinen M, et al. Preferences for receiving information among frail older adults and their informal caregivers: A qualitative study. Fam Prac. 2012;29:742–747. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans LR, Boyd EA, Malvar G, et al. Surrogate decision-makers' perspectives on discussing prognosis in the face of uncertainty. Am J Respir Critic Care Med. 2009;179:48–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-969OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romo RD, Wallhagen MI, Yourman L, et al. Perceptions of successful aging among diverse elders with late-life disability. Gerontologist. 2013;53:939–949. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King J, Yourman L, Ahalt C, et al. Quality of life in late life disability: “I don't feel bitter because I am in a wheelchair”. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:569–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaser BG, Strauss AL, Strutzel E. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Nurs Res. 1968;17:364. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anselm S, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Pine Forge Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18:179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun KL, Tanji VM, Heck R. Support for physician-assisted suicide exploring the impact of ethnicity and attitudes toward planning for death. Gerontologist. 2001;41:51–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwak J, Salmon JR. Attitudes and preferences of Korean-American older adults and caregivers on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1867–1872. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]