Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although the risk factors of human HCC are well known, the molecular pathogenesis of this disease is complex, and in general, treatment options remain poor. The use of rodent models to study human cancer has been extensively pursued, both through genetically engineered rodents and rodent models used in carcinogenicity and toxicology studies. In particular, the B6C3F1 mouse used in the National Toxicology Program (NTP) two-year bioassay has been used to evaluate the carcinogenic effects of environmental and occupational chemicals, and other compounds. The high incidence of spontaneous HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse has challenged its use as a model for chemically induced HCC in terms of relevance to the human disease. Using global gene expression profiling, we identify the dysregulation of several mediators similarly altered in human HCC, including re-expression of fetal oncogenes, upregulation of protooncogenes, downregulation of tumor suppressor genes, and abnormal expression of cell cycle mediators, growth factors, apoptosis regulators, and angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodeling factors. Although major differences in etiology and pathogenesis remain between human and mouse HCC, there are important similarities in global gene expression and molecular pathways dysregulated in mouse and human HCC. These data provide further support for the use of this model in hazard identification of compounds with potential human carcinogenicity risk, and may help in better understanding the mechanisms of tumorigenesis resulting from chemical exposure in the NTP two-year carcinogenicity bioassay.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, B6C3F1 mouse, microarray, gene expression analysis, comparative genomics

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in humans is one of the most common cancers worldwide, accounting for almost 500,000 new cases each year (Heindryckx et al. 2009). It is the fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer deaths globally (Parkin 2001). The disease carries a devastating prognosis, in that most cases remain undiagnosed until the disease has advanced to a metastatic stage, and the one-year cause-specific survival rates are less than 50% (Altekruse et al. 2009). Over 80% of human HCC occurs in regions of the globe in which there is a high rate of hepatitis B (HBV) or C (HCV) virus infection or in areas of high exposure to aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) as a result of contaminated grains or cereals, such as western/central Africa and eastern/southeast Asia (Suriawinata and Xu 2004; Tischoff and Tannapfe 2008). In addition, HBV interferes with the liver’s ability to metabolize aflatoxins, thus inducing a synergistic effect with AFB1 in the induction of HCC. Infection with these viruses or exposure to AFB1 leads to chronic hepatocelluar damage and necrosis, regeneration, chronic inflammation, and extracellular matrix remodeling and fibrosis, eventually culminating in chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and ultimately HCC. Other factors that lead to the development of chronic inflammation and ultimately to cirrhosis, setting the stage for HCC development, include chronic alcohol abuse, nutritional factors (e.g., vitamin B6 deficiency), and genetic/metabolic diseases including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFL), hemochromatosis, and α-antitrypsin deficiency (Suriawinata and Xu 2004; Teufel et al. 2007; Tischoff and Tannapfe 2008).

For decades, the B6C3F1 mouse has been used to evaluate various compounds for toxicology and carcinogenicity testing. Hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the most commonly observed neoplasms in National Toxicology Program (NTP) studies using the B6C3F1 mouse, with approximately 57% of positive tumor responses involving a liver tumor response following chemical exposure. The B6C3F1 mouse strain has a rather high proclivity to the development of spontaneous (non-treatment–related) HCC, with males averaging approximately 31% (range 16–56%, all routes, all vehicles) and females averaging 10% (range 2–46%, all routes, all vehicles; NTP Historical Controls Report, All Routes and Vehicles, March 2010). Increasing trends in the incidence of HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse resulting from chemical treatment are used to identify potential human carcinogens. In fact, with chemical treatment, the incidence of HCC in this strain may reach 100%, depending on the chemical. This finding suggests that either high chemical doses in this strain promote a preexisting spontaneous tumor response, or that this model is a very sensitive system to detect chemicals that are likely to cause molecular events leading to cancer, or a combination of both scenarios.

To understand the utility of this model in terms of hazard identification and relevance to human HCC, it is important to characterize the major differences and similarities between the disease in this strain and in humans. The incidence of spontaneous HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse is thought to occur in part as a result of the effects of testosterone, in that castrated males develop HCC at a lower rate that is closer to that of females, and females on testosterone supplementation develop HCC at a higher rate that is comparable to the rate in males (Ward et al. 1996). More recently, Rogers et al. (2007) have shown in the mouse that testosterone initiates an endocrine cascade within the central nervous system, resulting in periodic release of growth hormone from the anterior pituitary, leading to masculinization of the liver. The consequence of this sexual dimorphism of the liver includes a strong influence on liver cancer risk in males. Similar to the mouse, men are two to four times more likely than women to develop HCC (El-Serag and Rudolph 2007).

There are major differences in etiology between mouse and human HCC; the human disease arises predominantly within a background of chronic inflammation, hepatocellular degeneration, necrosis and regeneration, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix deposition (Cabibbo and Craxi 2010). In contrast, HCC in the mouse is thought to arise primarily as a genetic event influenced by various modifying factors (Maronpot 2009), and exhibiting a stepwise progression to HCC typically from altered hepatic foci to hepatocellular adenoma to HCC, without the advent of significant inflammation or cirrhosis seen in many of the predisposing conditions leading to human HCC. The exception to the latter are the mouse models of HCC that are induced by Helicobacter hepaticus infection (Rogers et al. 2004; Ward et al. 1994).

In addition to etiologic differences between both species, major differences in the molecular events leading to HCC also exist. For example, common changes that occur leading to human HCC include loss of p16, an important tumor suppressor gene, by methylation, deletion, or missense mutation (Matsuda 2008), Rb mutation or deletion (Zhang et al. 1994), and p53 mutation, which is commonly associated with hepatitis B infection and aflatoxin B1 exposure (Hussain et al. 2007). On the other hand, frequent molecular events in the development of HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse include a high rate of H-ras (Maronpot et al. 1995) and B-raf mutations (Buchmann et al. 2008), which are not commonly seen in human HCC. Despite these differences, there are significant similarities between the mouse and human in the genetic alterations leading to HCC. For example, β-catenin mutation is a common mutation in both mouse and human HCC, occurring in exon 2 of the mouse gene, corresponding with a well-known hotspot that is mutated in the human gene (de La Coste et al. 1998). Consistent with β-catenin mutation, differential alterations of Wnt/β-catenin pathway mediators is seen in both mouse and human HCC.

More recently, developments in the field of gene expression analysis and global gene profiling have greatly improved the knowledge of the genetic and epigenetic events (Lahousse et al. 2010) at play in HCC in humans and chemically induced HCC in mice. High-throughput gene expression using microarray technology has enabled the detection of gene expression of thousands of genes across the genome simultaneously using a variety of gene analysis algorithms, enabling comparison of large gene sets and major carcinogenic pathways between normal and tumorigenic tissues (Kittaka et al. 2008). We show that through application of genome-wide profiling of spontaneous HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse, a pathway-based approach of comparing biologically relevant pathways involved in hepatocarcinogenesis yields significant similarities in the molecular landscape of mouse and human HCC, despite significant differences in etiology.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Tissue Sampling

Spontaneous HCC and normal liver tissue were obtained from B6C3F1 mice serving as controls in a two-year NTP corn oil gavage bioassay. All mice were between the ages of 110 and 112 weeks of age at terminal sacrifice. Normal liver and spontaneous HCC were among the tissues collected at the time of necropsy; half of each tumor was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for histopathology, and the other half was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for molecular biology analysis. Twenty-four hours following fixation in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, samples were transferred to 70% ethanol, routinely processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathology. Normal livers from four male and two female B6C3F1 mice and spontaneous HCC from an additional four males and two females were used for molecular analysis. Normal liver samples were acquired from the left liver lobe in animals that did not have a liver tumor. All samples for molecular analysis were paired with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded histopathology samples for morphologic analysis and immunohistochemical localization of proteins.

Extraction and Quantification of RNA, Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

Extraction of RNA was performed using the Invitrogen PureLink Mini kit (Invitrogen cat. no. 12183-018A). Frozen tissue samples were lysed and homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using a rotor-stator homogenizer. Isolation of RNA was performed according to the mini kit protocol. On-column DNase treatment was performed using the Invitrogen PureLink DNase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to purify the RNA samples. RNA concentration and 260/280 ratio were measured on a bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). RNA quality was checked on Embi Tec Precast RNA gels (Embi Tec, San Diego, CA). Samples were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until used.

RNA Labeling and Microarray Hybridization

Gene expression analysis was conducted using Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 GeneChip arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). One microgram of total RNA was amplified as directed in the Affymetrix One-Cycle cDNA Synthesis protocol. Fifteen micrograms of amplified biotin-cRNA were fragmented and 10 µg were hybridized to each array for 16 hours at 45°C in a rotating hybridization oven using the Affymetrix Eukaryotic Target Hybridization Controls and protocol. Array slides were stained with streptavidin/phycoerythrin using a double-antibody staining procedure and then washed using the EukGE-WS2v5 protocol of the Affymetrix Fluidics Station FS450 for antibody amplification.

Data Processing

Arrays were scanned in an Affymetrix Scanner 3000 and data were obtained using the GeneChip Command Console Software (AGCC, version 1.1). Fluorescent pixel intensity measurements were acquired from the arrays and processed using the MAS5 algorithm (Hubbell et al. 2002). The signals were background-subtracted and averaged (across probes within a probe set) using a mean Tukey biweight function. Control probes on the array were removed, and then the gene expression data from the remaining probe sets were normalized across the groups of samples using the robust multi-array analysis methodology (Irizarry et al. 2003) in the R statistical software environment. Robust multi-array analysis adjusts the gene expression measurements across the arrays in a series by applying quantile (ranked based) normalization at the probe set level. The goal of the quantile method is to make the distribution of probe set intensities for each array in a set of arrays the same. Finally, robust multi-array analysis fits a linear additive model to the log-transformed perfect match (PM) values using median polish to reduce noise. Microarray data files (.cel) and associated annotations have been submitted to the GEO database: Accession GSE26538 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=bxmftqyumwqwktu&acc=GSE26538).

Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

Robust multi-array analysis normalized data were used for statistical analysis. For each probe set, pairwise comparisons were made using a bootstrap t test while controlling the mixed directional false discovery rate (Guo et al. 2010). This methodology controls for the overall false discovery rates for multiple comparisons as well as directional errors when declaring a gene to be up- or downregulated. The bootstrap methodology does not make any assumptions of normality and is also robust to the underlying variance structure.

For each probe set, pairwise t tests were performed between the groups of samples. The null hypothesis is that none of the pairwise contrasts is different from 0 versus at least one pairwise difference is not equal to 0. If for a given probe set the null hypothesis is rejected, multidimensional false discovery rate (Guo et al. 2010) is determined in a “post-hoc” manner to control for multiple testing and to account for the errors made in assigning the direction of differential change (i.e., positive or negative). If no significant probe sets are detected, then for each pairwise contrast where for a given probe set the null hypothesis is rejected, the standard false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) is determined to control for multiple testing.

Bioinformatics Analyses

Partek Genomics Suite, version 6.4 (release date September 22, 2009) (Partek, St. Louis, MO) was used to perform principal component analysis on the normalized data and to generate heat maps to compare the normal liver (N) and spontaneous (S) HCC samples for differentially expressed probe sets. Principal component analysis uses a linear transformation to reduce the dimension of the data from n probe sets to k principal components (PC). The first three PC that capture the majority of the variation in the data were used to visualize the spatial relationship of the N and S samples. Agglomerative hierarchical unsupervised clustering was used to cluster the genes (rows) and samples (columns), where Pearson’s dissimilarity was used as the distance measure and Ward’s method was used to evaluate distance between clusters.

The NextBio analysis tool (http://www.nextbio.com) was used to compare mouse HCC to human HCC at the level of global gene expression and pathway enrichment. NextBio is a curated and correlated repository of experimental data derived from an extensive set of public sources (e.g., ArrayExpress and GEO) that allows the user to compare patterns of gene expression in his or her experiment to thousands of genomic signatures derived from published datasets. Statistical analysis is carried out using rank-based enrichment analysis to compute pairwise correlation scores of the uploaded dataset and all studies contained in NextBio. The statistical analysis method used by NextBio is referred to as a “Running Fischer” and is very similar to gene set enrichment analysis (Subramanian et al. 2005). A detailed explanation of the analysis protocol used by NextBio is described elsewhere (Kupershmidt et al. 2010). For our NextBio analysis, all 4,510 probe sets (of which only 4,509 were recognized by the database) exhibiting significant differential expression in mouse HCC were uploaded along with fold change values. The initial correlation analysis identified a number of different human HCC genomic signatures (referred to as biosets in NextBio) as being positively correlated with human HCC and other human liver–centric pathological states. Four human HCC biosets exhibiting the highest rank correlation with mouse HCC (advanced and very advanced HCC patients from GEO Accession GSE6764 [Wurmbach et al. 2007]; liver tumor-vs- paired normal liver from GEO Accession GSE5364 [Yu et al. 2008]; HCC stage T3-vs-normal liver from GEO Accession GSE6222 [Liao et al. 2008]) were selected for more in depth comparison of genes and pathways. In order to carry out the comparison, all five biosets (one mouse and four human) were loaded into the Advanced Query tool in NextBio. In the first step, all concordant genes were identified between mouse and at least one human HCC bioset. Further queries were then performed to identify mouse HCC-specific and human HCC-specific genes. The biogroup analysis tool was then used to identify pathways that were enriched in mouse and human HCC samples. Pathway analysis in NextBio is distributed into up- and downregulated genes, and therefore two p values are reported for all pathways that contain genes in a bioset. To simplify the comparison with mouse HCC, up- and downregulated pathway p values for all reported pathways in the human HCC samples were averaged. The averaged up- and downregulated p values for all pathways were then compared with the up- and downregulated p values from the mouse HCC pathway analysis. A pathway was considered significantly up- or downregulated if its nominal p value was >.01 (−log10 > 2).

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software, version 8.8, and canonical pathway content version 3204 were used to build gene interactions from the genes related to human HCC and other cancers. Genes in these groups that were used for network creation were identified based on extensive review of the current literature by the authors. All genes in the biological categories that were network eligible (interact with another biological entity in the IPA Knowledge Base) were considered in network generation. In the network generation process, IPA identifies groups of eligible molecules that exhibit overconnectivity relative to all molecules to which they are connected in the Knowledge Base.

Western Blotting and Immunohistochemistry

For Western blotting, tumor and normal liver lysates were prepared by pulverizing tissues with a mortar and pestle while they were submersed in liquid nitrogen, followed by tissue homogenization using a rotor-stator homogenizer in standard RIPA buffer containing Halt phosphatase inhibitor (Pierce, Thermo-Scientific, Rockford, IL) and Complete Mini protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Lysates were centrifuged, the supernatant collected, and total protein was measured using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo-Scientific). For the analysis of differentially expressed proteins by Western blotting, the following antibodies at corresponding dilutions were employed: goat polyclonal β-catenin (C-18; sc-1496, 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); mouse monoclonal E-cadherin (C20820, 1:2,000; Transduction Labs, Lexington, KY); rabbit polyclonal glutamine synthetase (ab49873, 1:5,000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA); goat polyclonal α-fetoprotein (AF5369, 1:1.0 µg/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); and donkey anti-mouse β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

For immunohistochemistry, unstained, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval using a decloaker. Following nonspecific blocking steps, polyclonal and monoclonal primary antibodies were applied at the following dilutions: polyclonal goat anti-β-catenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:50; monoclonal mouse anti-E-cadherin antibody (Transduction Labs) at 1:50; polyclonal rabbit anti-glutamine synthetase (Abcam) at 1:10,000; polyclonal rabbit anti-cyclin D1 (LabVision, Fremont, CA) at 1:100; polyclonal rabbit anti-c-Myc (Abcam) at 1:25; monoclonal rat anti-Ki67 (Dako, Carpenteria CA) at 1:80; and rabbit polyclonal anti-Birc5 antibody was applied at 1:500. Negative controls substituted normalized serum for the primary antibody. Positive controls included tissues known to exhibit positive expression of proteins of interest. The avidin-biotin enzyme complex was used for primary antibody binding amplification, and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine was used for visualization. Sections were then dehydrated in graded alcohols and coverslipped.

Results

Histologic Phenotypes of Mouse Spontaneous HCC Resemble Human HCC

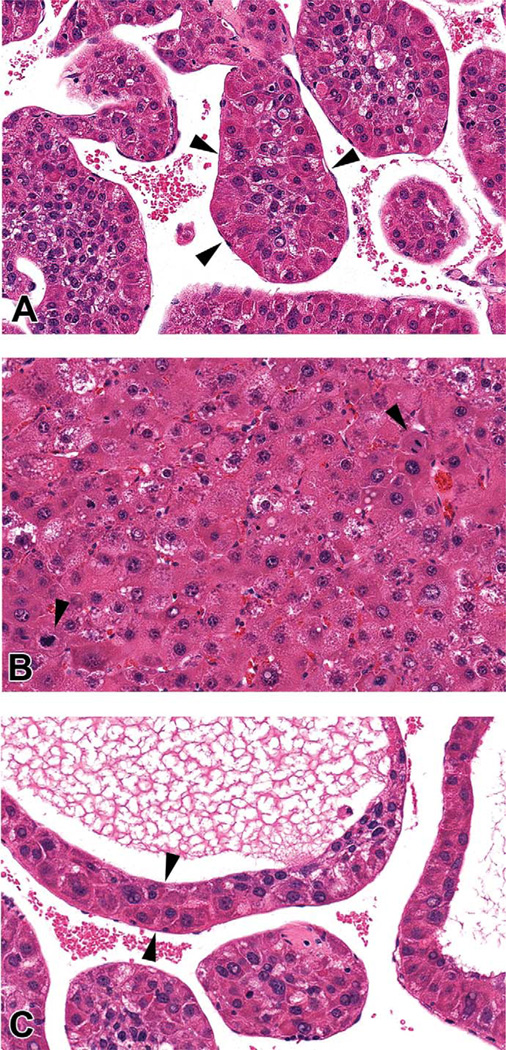

According to the World Health Organization classification of tumors, there are various architectural patterns of human HCC, including trabecular, pseudoglandular, and compact/solid patterns, and a rare scirrhous form (Hirohashi et al. 2000). In spontaneous HCC in B6C3F1 mice, there are multiple histologic phenotypes that are similar to those seen in humans, including trabecular, solid, and less often, pseudoglandular patterns. Scirrhous variants are not observed.

Histopathologic examination of the liver tumors collected at necropsy for this study revealed HCC with the three patterns characteristic of both mouse and human HCC (Figure 1). Trabecular patterns were characterized by cords of neoplastic cells greater than three cell layers thick, often separated by dilated, blood-filled spaces. Solid areas generally lacked an identifiable pattern and were typically anaplastic, with marked pleomorphism and compressed, slit-like sinusoidal spaces. Pseudoglandular forms were characterized by a central clear zone rimmed by neoplastic hepatocytes, often only a few cells thick. These patterns were often intermixed, as in human HCC.

Figure 1.

Morphologic characteristics of spontaneous HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse. Tumors were characterized by several histologic phenotypes, often within the same tumor, including (A) trabecular, composed of variably sized cords greater than three hepatocytes in thickness (arrowheads); (B) solid, composed of sheets of neoplastic cells with no apparent architecture, often exhibiting marked pleomorphism and a robust mitotic rate (arrowheads); and less frequently (C) pseudoglandular phenotypes, typified by variably sized luminal structure formation lined by few to multiple layers of neoplastic hepatocytes (arrowheads), hematoxylin and eosin, 40×.

Global Gene Expression Profiling of Spontaneous HCC in B6C3F1 Mice Identifies Mediators Involved in Human Hepatocarcinogenesis

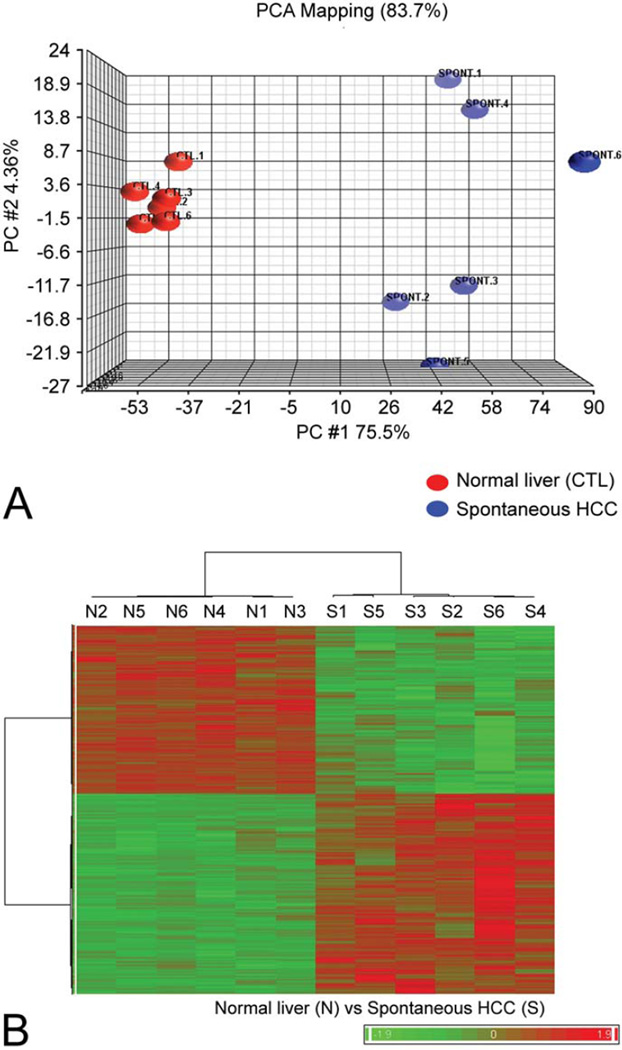

From approximately 45,101 probe sets (representing 21,901 annotated genes) on the array, 4,510 (mapped to 3,598 genes) probe sets were identified as differentially expressed (p < .05) in mouse HCC compared to paired normal mouse liver (Supplementary Table 1; a supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://tpx.sagepub.com/supplemental). Principal component analysis of the differentially expressed genes from all the comparisons illustrated clear separation of HCC and normal liver samples (Figure 2A). Principal component 1 (PC1), with about 75% of the variation of the data captured, separates the two sample types. Hierarchical clustering revealed two clusters of genes with expression patterns upregulated in HCC samples but downregulated in the normal liver samples (and vice versa) separating the two groups (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Microarray analysis of spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the B6C3F1 mouse. (A) Principal component analysis of global gene expression of spontaneous HCC compared to normal liver (CTL). Principal component analysis mapping illustrates significant similarities within groups, as evidenced by tight clustering of samples, as well as significant differences in overall gene expression between groups. (B) Heat map illustrating significant differences in global gene expression between normal liver (N) and spontaneous HCC (S). Red indicates upregulation and green indicates downregulation of gene expression. Partek Genomics Suite (6.4) was used to generate heat maps to compare the normal liver (N) and spontaneous HCC (S) samples using an unsupervised learning approach. Agglomerative hierarchical clustering was used to cluster the genes (rows) and samples (columns), in which Pearson’s dissimilarity was used as the distance measure and Ward’s method was used to evaluate distance between clusters.

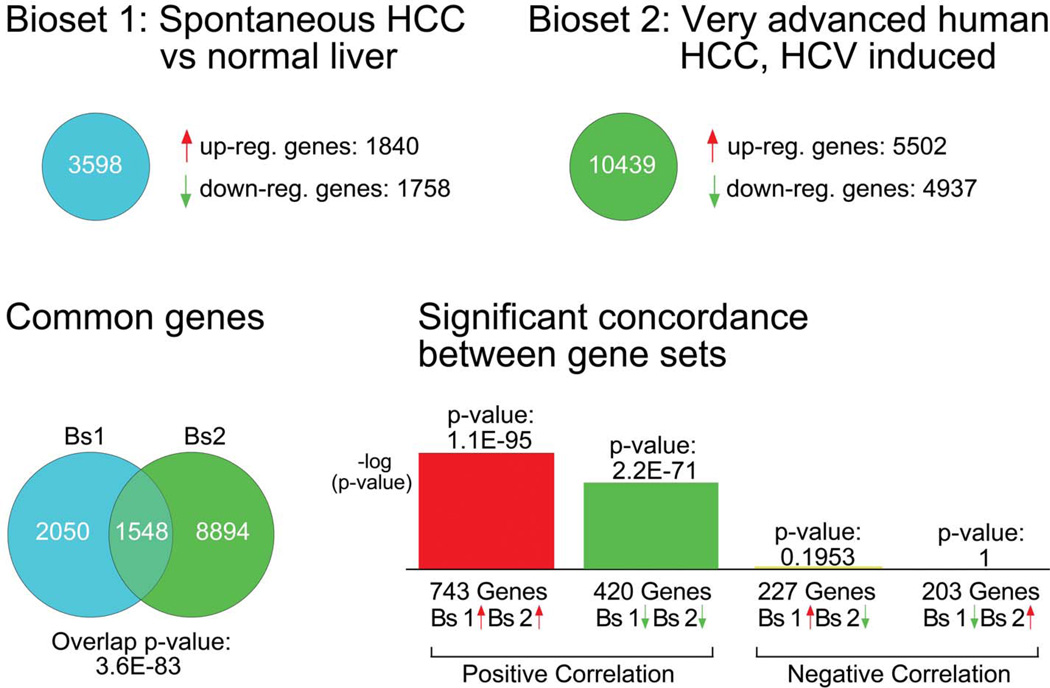

Using NextBio software, we compared the differentially expressed genes in the mouse HCC bioset across a database of curated human HCC biosets (Figure 3) (a bioset is the list genes exhibiting differential expression in a given comparison, e.g., human HCC versus normal liver). Four of the most concordant human biosets (most similar to the mouse bioset) from the literature were identified (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Figure 1) and used for comparison analysis. Using the NextBio Advanced Query tool, 1,568 genes were identified that exhibited differential expression in mouse HCC and in at least one of the four human HCC biosets (Supplementary Table 3). One thousand six-hundred seven genes that were differentially expressed in mouse HCC were not differentially expressed in any of the human HCC biosets (Supplementary Table 4). Four thousand four hundred twenty-eight genes that were differently expressed in three out of four human HCC biosets were not differentially expressed in mouse HCC (Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 3.

Significant concordance between spontaneous B6C3F1 mouse hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) dataset and very advanced human HCC. Using NextBio software, there are 1,163 concordant genes shared between the mouse and human HCC datasets, with 743 similarly upregulated (p = 1.1E-95) and 420 similarly downregulated (p = 2.2E-71). Human HCC dataset: GEO Accession GSE6764.

Directional pathway enrichment analysis (p values of the up- and downregulated genes are calculated independently) of the genes differentially expressed from mouse HCC and human HCC was performed to allow for a pathway level comparison between the two groups. Results of the biogroup individual analyses can be found in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7, respectively. For purposes of mouse versus human pathway comparisons, a pathway was considered enriched if it attained a nominal p value < .01 in the case of mouse HCC or a four-biosets mean nominal p value < .01 (Supplementary Table 7, columns AC and AD). Pathways that were concordantly upregulated in mouse and human HCC include cell cycle, DNA replication, cell cycle G1 to S control, and cell cycle G2/M checkpoint, among others (Table 1). A sizable fraction of pathways were solely upregulated in mouse (e.g., ribosome) or human (e.g., CDC25 and CHK1 regulatory pathway in response to DNA damage; Supplementary Table 8). A large number of pathways were concordantly downregulated in mouse and human HCC (Table 2); however, there were a few with solely downregulated in mouse (e.g., oxidative phosphorylation) and human HCC (e.g., complement and coagulation cascades; Supplementary Table 9).

Table 1.

Top upregulated concordant canonical pathways in spontaneous mouse and human hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Canonical pathways | Mouse (−log[P value]) |

Human (−log[P value]) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle | 14.2 | 15.6 |

| DNA replication reactome | 8.6 | 8.4 |

| Cell cycle G1 to S control reactome | 9.8 | 7.3 |

| Cell cycle G2/M check point | 7.8 | 7.0 |

| mRNA processing reactome | 6.3 | 6.6 |

| P53 signaling pathway | 3.7 | 6.6 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 3.2 | 4.7 |

| Activation of Src by protein-tyrosine phosphatase α |

2.1 | 4.7 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| RB tumor suppressor pathway | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| Cell cycle G1/S check point | 4.2 | 3.1 |

| MTA3 pathway | 2.2 | 2.9 |

| Phosphoinositide 3 kinase pathway | 3.3 | 2.7 |

| Insulin receptor pathway in cardiac myocytes |

3.1 | 2.2 |

| Cell communication | 2.0 | 2.1 |

Table 2.

Top downregulated concordant canonical pathways in spontaneous mouse and human hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Canonical pathways | Mouse (−log[P value]) |

Human (−log[P value]) |

|---|---|---|

| Valine leucine and isoleucine degradation | 24.8 | 24.9 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 27.8 | 24.5 |

| Propanoate metabolism | 17.8 | 19.9 |

| PPAR signaling pathway | 13.2 | 16.9 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 |

8.3 | 15.4 |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 15.2 | 15.1 |

| β-alanine metabolism | 13.3 | 14.8 |

| Bile acid biosynthesis | 14.0 | 13.3 |

| Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism | 8.8 | 10.0 |

| Mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation | 16.1 | 9.5 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 13.1 | 9.0 |

| Lysine degradation | 18.3 | 8.4 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 3.1 | 7.9 |

| Urea cycle and metabolism of amino groups |

4.0 | 6.9 |

| β-oxidation of fatty acids | 5.0 | 6.5 |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 4.0 | 5.6 |

| Androgen and estrogen metabolism | 5.3 | 2.4 |

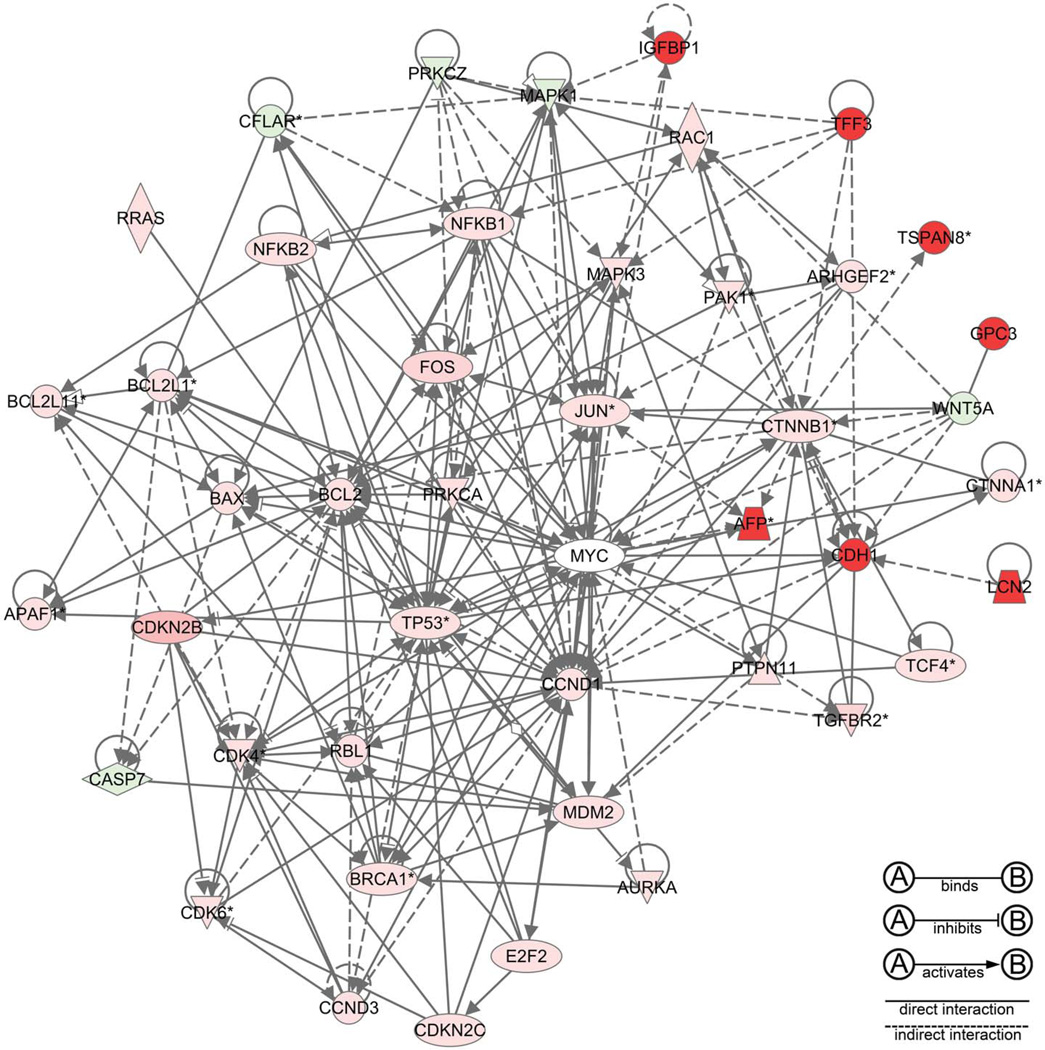

Significantly differentially expressed genes that were identified on the array were organized into biologically relevant categories (Table 3) based on extensive literature review, which incorporated those genes that are associated with hepatocarcinogenesis (Figure 4) and other cancers in humans, including fetal oncogenes, protooncogenes, and tumor suppressor genes (Figure 5), cell cycle regulators and growth factors (Figure 6), transcription factors, anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic genes, DNA damage repair genes, and genes involved in angiogenesis and tissue remodeling. The top twenty most upregulated and downregulated genes in spontaneous HCC from B6C3F1 mice are shown in Table 4. These data illustrate that there are significant changes in global gene expression in spontaneous HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse that are similar to those reported in human HCC, at both the individual gene and pathway levels. Differentially regulated genes were validated by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Western blotting, and immunohistochemistry.

Table 3.

Dysregulated genes identified on microarray of spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Symbol | Name | Fold change | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Fetal oncogenes | |||

| Afp | α-fetoprotein | 439.89 | 1.0E-04 |

| Bex1 | Brain-expressed X-linked gene 1 | 242.19 | 1.0E-04 |

| H19 | H19 maternally imprinted transcript | 91.90 | 1.0E-04 |

| Gpc3 | Glypican-3 | 37.66 | 1.0E-04 |

| Scd2 | Stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 2 | 20.06 | 1.0E-04 |

| Bmi1 | B-lymphoma Moloney murine leukemia virus 1 | 1.65 | 1.0E-04 |

| 1.2 Protooncogenes | |||

| Fos | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene | 4.96 | 2.0E-04 |

| Jun | jun oncogene | 2.56 | 2.0E-04 |

| JunB | jun B proto-oncogene | 4.26 | 1.0E-03 |

| JunD | jun D proto-oncogene | ||

| Relb | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene B | 2.35 | 1.0E-04 |

| Ets2 | v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene 2 | 2.82 | 1.1E-03 |

| 1.3 Tumor suppressor genes | |||

| Pten | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | −1.49 | 4.0E-04 |

| Gas1 | Growth-specific arrest 1 | −5.26 | 1.0E-04 |

| Wwox | WW domain containing oxidoreductase | −1.31 | 2.0E-03 |

| 1.4 Cell cycle regulators | |||

| Tp53 | Tumor protein 53 | 1.42 | 1.0E-04 |

| Mdm2 | Mdm2 p53 binding protein homolog | 1.7 | 2.0E-03 |

| CcnA2 | Cyclin A2 | 2.46 | 1.0E-04 |

| CcnB1 | Cyclin B1 | 2.50 | 2.0E-04 |

| CcnB2 | Cyclin B2 | 3.92 | 2.0E-04 |

| CcnD1 | Cyclin D1 | 3.21 | 2.3E-03 |

| Cdkn2b | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B (p15) | 8.01 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cdk4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | 1.42 | 5.0E-04 |

| Cdk6 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | 1.86 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cdk7 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 7 | 1.4 | 1.0E-03 |

| Mcm6 | Minichromosome maintenance complex 6 | 5.10 | 2.0E-04 |

| Ki67 | Antigen identified by antibody Ki-67 | 5.00 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cdkn2c | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2C (p18) | 3.26 | 1.6E-03 |

| Cdc2 | Cell division cycle 2, G1 to S and G2 to M | 3.30 | 4.0E-04 |

| Cdc6 | Cell division cycle 6 homolog | 1.56 | 1.0E-04 |

| Aurka | Aurora kinase A | 2.85 | 2.0E-04 |

| Plk1 | Polo-like kinase 1 | 1.36 | 2.0E-03 |

| Mad211 | MAD2 mitotic arrest deficient-like 1 | 2.04 | 1.0E-04 |

| 1.5 Transcription factors | |||

| Top2a | Topoisomerase α 2a | 4.30 | 3.0E-04 |

| Ets2 | v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 2 | 2.82 | 1.1E-03 |

| Tcf19 | Transcription factor 19 | 1.49 | 7.0E-04 |

| Tcf12 | Transcription factor 12 | 1.26 | 1.4E-03 |

| 1.6 Growth pathways | |||

| Tspan8 | Tetraspanin 8 | 188.58 | 1.0E-04 |

| Tff3 | Trefoil factor 3 | 44.91 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cdh1 | E-cadherin | 32.95 | 1.0E-04 |

| Igfbp1 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 | 26.17 | 1.0E-04 |

| Ctnnb1 | β-catenin | 1.48 | 1.0E-04 |

| Tgfbr2 | Transforming growth factor, beta receptor II | 4.95 | 1.0E-04 |

| Tgfa | Transforming growth factor-alpha | 2.41 | 2.0E-04 |

| Tgif1 | TGFB-induced factor homeobox 1 | 2.88 | 1.0E-04 |

| Smad3 | SMAD family member 3 | 1.66 | 4.0E-04 |

| Mapk3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 | 1.63 | 6.0E-04 |

| Nfkb1 | Nuclear factor κ gene enhancer in B-cells 1 | 1.56 | 1.0E-04 |

| Nfkb2 | Nuclear factor κ gene enhancer in B-cells 2 | 1.49 | 2.0E-04 |

| RhoC | ras homolog gene family, member C | 6.44 | 1.0E-04 |

| Ptpn11 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 11 | 1.27 | 1.7E-03 |

| Pias | Protein inhibitor of activated STAT, 1 | 1.52 | 2.1E-03 |

| Stat6 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 | 1.54 | 3.0E-04 |

| Egr1 | Early growth response 1 | 7.48 | 3.0E-04 |

| 1.7 Apoptosis mediators | |||

| Apaf1 | Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 | 2.00 | 2.0E-04 |

| Birc5 | Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 | 4.12 | 1.0E-04 |

| Bc12 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 | 1.29 | 1.8E-03 |

| Bc1211 | Bc12-like 1 (Bcl-XL) | 1.47 | 3.0E-04 |

| Bc12111 | Bc12-like 11 | 2.68 | 4.0E-04 |

| Apaf1 | Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 | 2.00 | 2.0E-04 |

| Casp1 | Caspase 1 | 3.19 | 2.0E-04 |

| Casp4 | Caspase 4 | 4.02 | 9.0E-04 |

| Casp12 | Caspase 12 | 6.76 | 4.0E-04 |

| Casp7 | Caspase 7 | −1.43 | 2.1E-03 |

| Bax | Bc12-associated X protein | 1.63 | 2.0E-04 |

| Bc110 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 10 | 1.57 | 1.0E-04 |

| Tnfrsf1a | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, 1A | 1.59 | 1.0E-04 |

| 1.8 DNA damage repair genes | |||

| Brca1 | Breast cancer 1, early onset | 2.98 | 1.0E-04 |

| Rad51 | Rad51 homolog | 1.69 | 1.3E-03 |

| Rad52 | Rad52 homolog | 1.48 | 1.3E-03 |

| Msh2 | mutS homolog 2 | 1.34 | 2.4E-03 |

| Msh6 | mutS homolog 6 | 1.43 | 4.0E-04 |

| Xrcc5 | X-ray complementing defective repair 5 | 1.28 | 7.0E-04 |

| 1.9 Angiogenesis and tissue remode | |||

| Vegf-c | ling Vascular endothelial growth factor-C | 1.78 | 8.0E-04 |

| Pdgf-a | Platelet-derived growth factor-A | 2.58 | 2.0E-04 |

| Sparc | Secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich (osteonectin) | 4.18 | 3.0E-04 |

| Mmp14 | Matrix metalloproteinase 14 | 2.49 | 1.7E-03 |

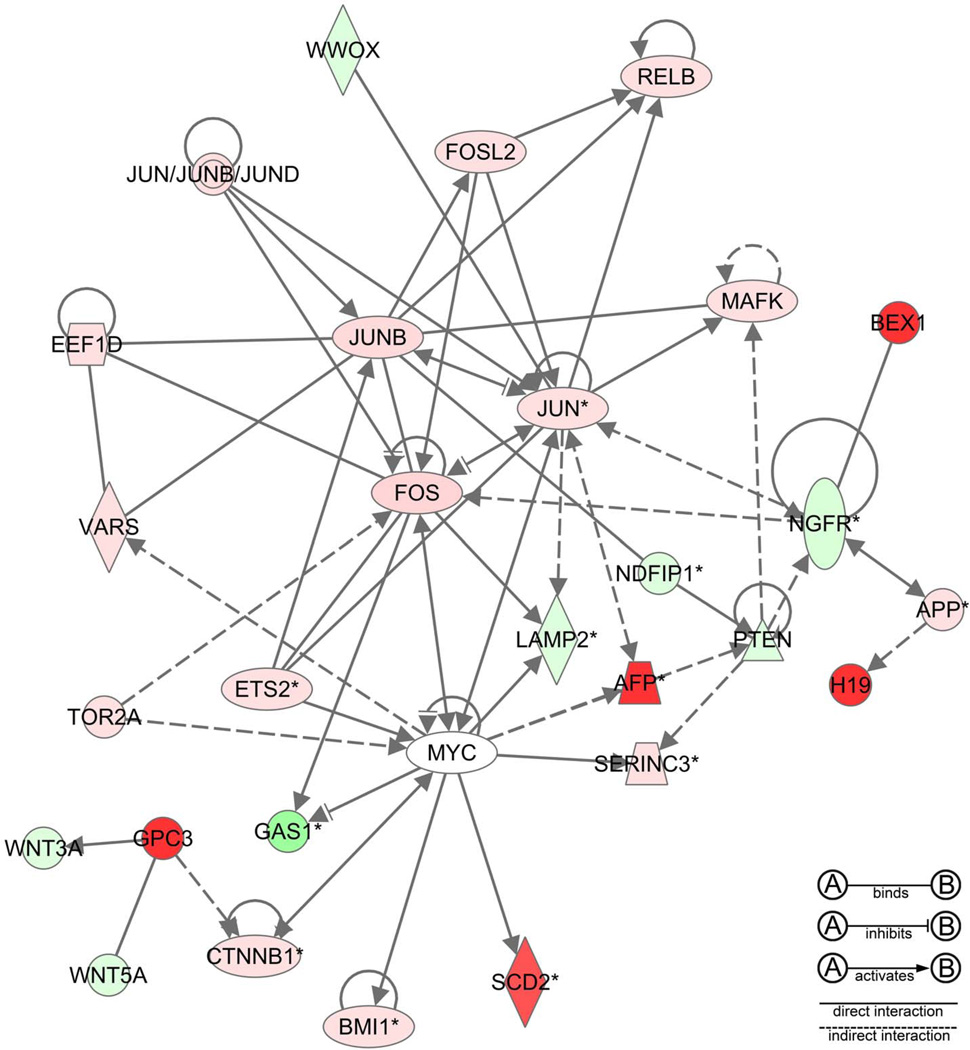

Figure 4.

A network produced by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes in spontaneous mouse hepatocellular carcinoma, illustrating the interactome of mediators implicated in the pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma (red, upregulation; green, downregulation).

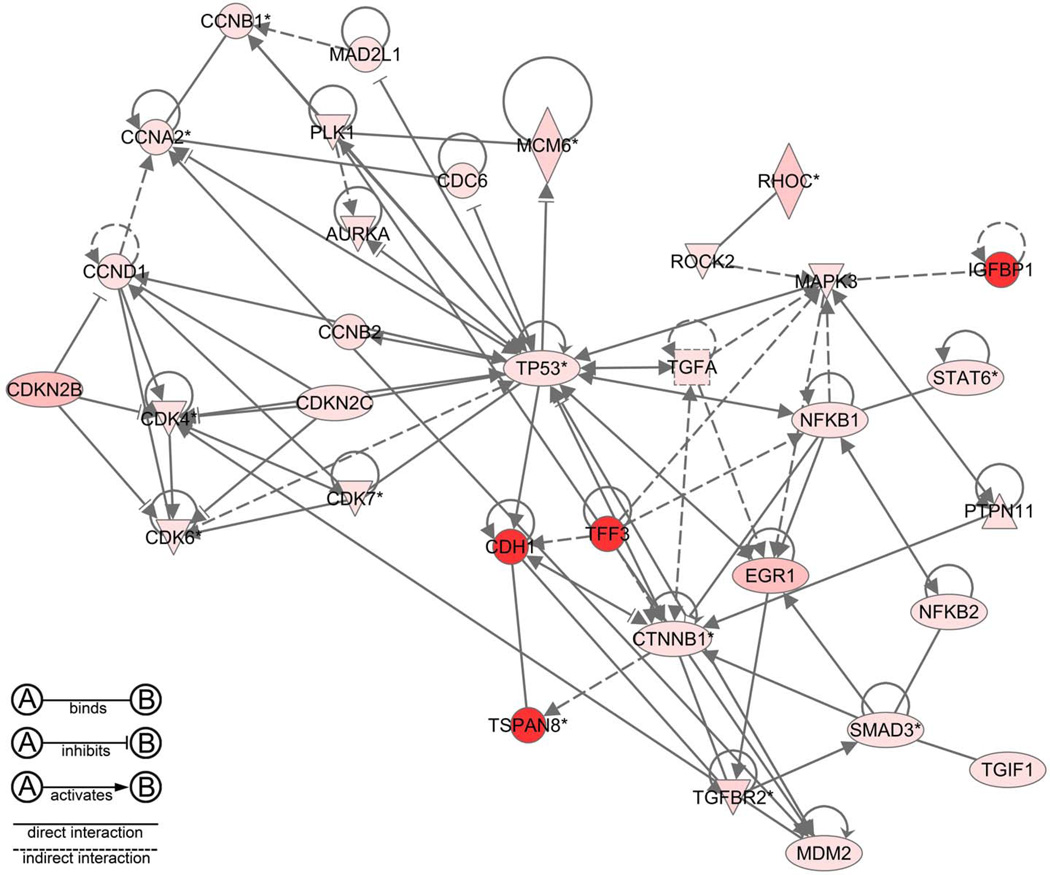

Figure 5.

A network produced by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of spontaneous mouse hepatocellular carcinoma illustrating the interactome of fetal oncogenes, protooncogenes, and cell cycle mediators that are expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (red, upregulation of gene expression; green, downregulation). CMYC was upregulated by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction but was not represented on the microarray.

Figure 6.

A network produced by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of spontaneous mouse hepatocellular carcinoma illustrating the interactome of growth factors and cell cycle mediators expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (red, upregulation; green, downregulation).

Table 4.

Top upregulated and downregulated in spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma in B6C3F1 mice.

| Symbol | Entrez Gene Name | Fold change | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top 20 upregulated genes | |||

| Afp | α-fetoprotein | 439.890 | 1.0E-04 |

| Bex1 | Brain expressed, X-linked 1 | 242.191 | 1.0E-04 |

| Tspan8 | Tetraspanin 8 | 188.576 | 1.0E-04 |

| H19 | H19, imprinted maternally expressed transcript | 91.900 | 1.0E-04 |

| Tff3 | Trefoil factor 3 (intestinal) | 44.911 | 1.0E-04 |

| Gpc3 | Glypican 3 | 37.661 | 1.0E-04 |

| Ly6d | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus D | 36.963 | 1.0E-04 |

| Akr1c3 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C3 | 34.631 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cpe | Carboxypeptidase E | 33.568 | 2.0E-04 |

| Cdh1 | Cadherin 1, type 1, E-cadherin (epithelial) | 32.945 | 1.0E-04 |

| Lcn2 | Lipocalin 2 | 29.919 | 1.0E-04 |

| Igfbp1 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 | 26.173 | 1.0E-04 |

| Esm1 | Endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | 23.984 | 2.0E-04 |

| Itih5 | Inter-α (globulin) inhibitor H5 | 23.868 | 1.0E-04 |

| Prom1 | Prominin 1 | 23.769 | 3.0E-04 |

| Slpi | Secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor | 21.039 | 2.0E-04 |

| Scd2 | Stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 2 | 20.057 | 1.0E-04 |

| Lpl | Lipoprotein lipase | 19.173 | 2.0E-04 |

| Nid1 | Nidogen 1 | 17.545 | 1.0E-04 |

| Ddr1 | Discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinase 1 | 17.376 | 5.0E-04 |

| Top 20 downregulated genes | |||

| Elov13 | Elongation of very long chain fatty acids like-3 | −52.820 | 1.9E-03 |

| Cyp8b1 | Cytochrome P450, family 8, subfamily B, polypeptide 1 | −39.397 | 1.0E-04 |

| Hamp | Hepcidin antimicrobial peptide | −35.531 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cyp2c19 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily C, polypeptide 19 | −32.424 | 2.0E-04 |

| Dct | Dopachrome tautomerase | −30.065 | 1.0E-04 |

| Es22 | Esterase 22 | −27.133 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cyp2f1 | Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily F, polypeptide 1 | −25.176 | 1.4E-03 |

| Ca3 | Carbonic anhydrase III, muscle specific | −13.852 | 2.0E-04 |

| Upp2 | Uridine phosphorylase 2 | −13.604 | 2.9E-03 |

| Cyp7a1 | Cytochrome P450, family 7, subfamily A, Polypeptide 1 | −13.604 | 1.0E-04 |

| Serpinb1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 1 | −12.185 | 5.0E-04 |

| Colec10 | Collectin subfamily member 10 (C-type lectin) | −11.066 | 2.0E-04 |

| Cyp2j5 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily j, polypeptide 5 | −10.411 | 7.0E-04 |

| Ccrn41 | CCR4 carbon catabolite repression 4-like (S. cerevisiae) | −9.781 | 4.0E-04 |

| Ar | Androgen receptor | −9.357 | 1.0E-04 |

| Cyp2b6 | Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily B, polypeptide 6 | −8.282 | 2.2E-03 |

| Plekhb1 | Pleckstrin homology domain containing, family B 1 | −7.722 | 1.0E-04 |

| Thrsp | Thyroid hormone responsive (SPOT14 homolog, rat) | −7.301 | 1.0E-04 |

| Retsat | Retinol saturase (all-trans-retinol 13,14-reductase) | −6.989 | 2.1E-03 |

| Inmt | Indolethylamine N-methyltransferase | −6.859 | 2.0E-04 |

QRT-PCR Analysis of Select Genes Differentially Expressed in Microarray Analysis of Spontaneous Mouse HCC

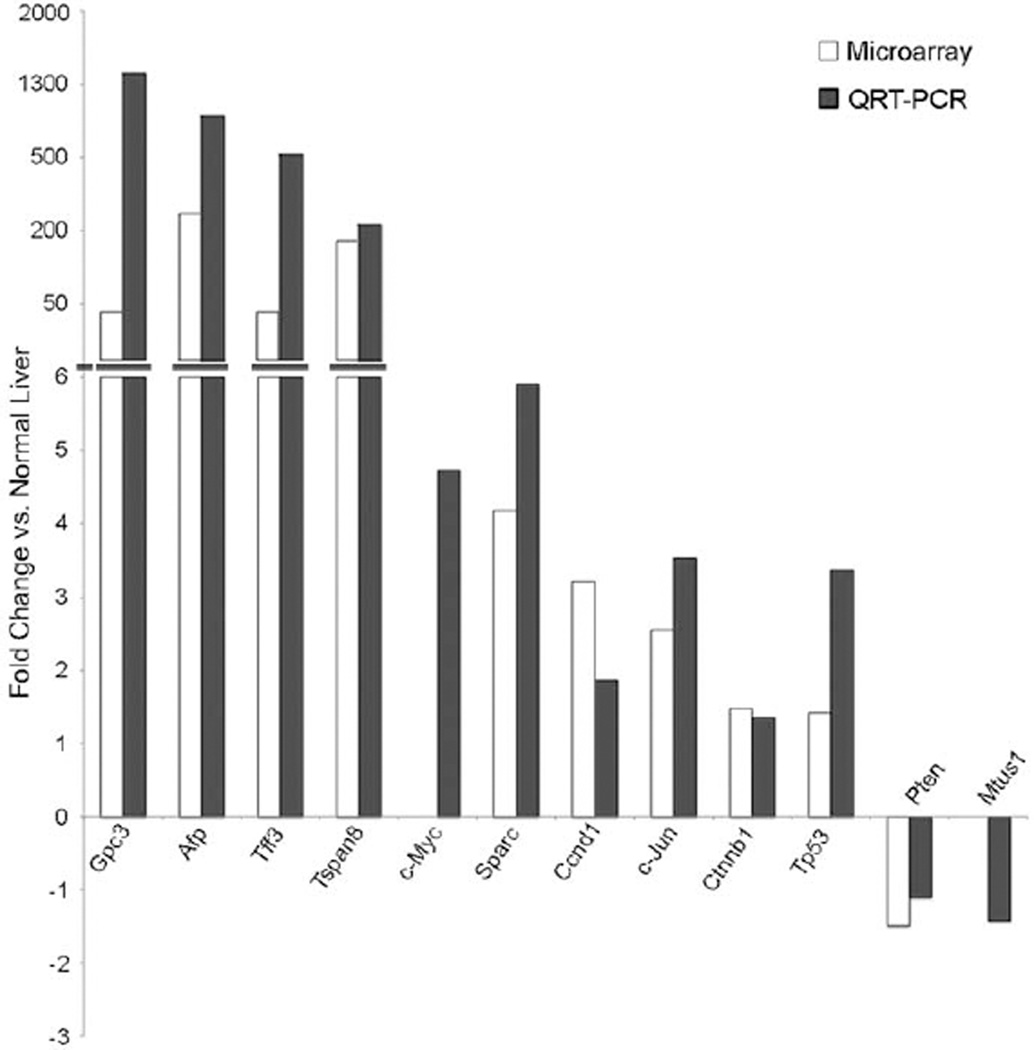

Several genes were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR to validate the changes observed in microarray analysis. Criteria for validation of genes were based on important mediators involved in human HCC as well as those genes involved in multiple different biologic processes in the liver. These genes included Afp, Gpc3, Tff3, Tspan8, c-Myc, Sparc, Ccnd1, c-Jun, Ctnnb1, Tp53, Pten, and Mtsu1. RNA expression of select genes as assessed by QRT-PCR matched the directional change of expression observed in the microarray analysis (Figure 7). The expression of c-Myc, which was not differentially expressed on the array, was included in the analysis because of its role in human HCC (Peng et al. 1993; Thorgeirsson and Grisham 2002; Yuen et al. 2001). By QRT-PCR, the expression of c-Myc was increased in spontaneous HCC almost five-fold over that of normal liver. Similarly an important tumor suppressor gene, mitochondrial tumor suppressor-1 (Mtus1), which was also not differentially expressed on the array, was investigated because of its role in human HCC (Di Benedetto et al. 2006) and was found to be downregulated in spontaneous mouse HCC (−1.5 vs. normal mouse liver).

Figure 7.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) validation of important mediators in spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma in the B6C3F1 mouse. Several mediators important in the development and progression of HCC in humans are similarly dysregulated in HCC of mice, as shown by both QRT-PCR and microarray. Other important mediators of human HCC are also shown by QRT-PCR to be dysregulated, although not differentially expressed by microarray analysis (c-Myc, Mtsu1).

Protein Expression in Mouse Spontaneous HCC Validated Several Pathways Dysregulated in Human HCC

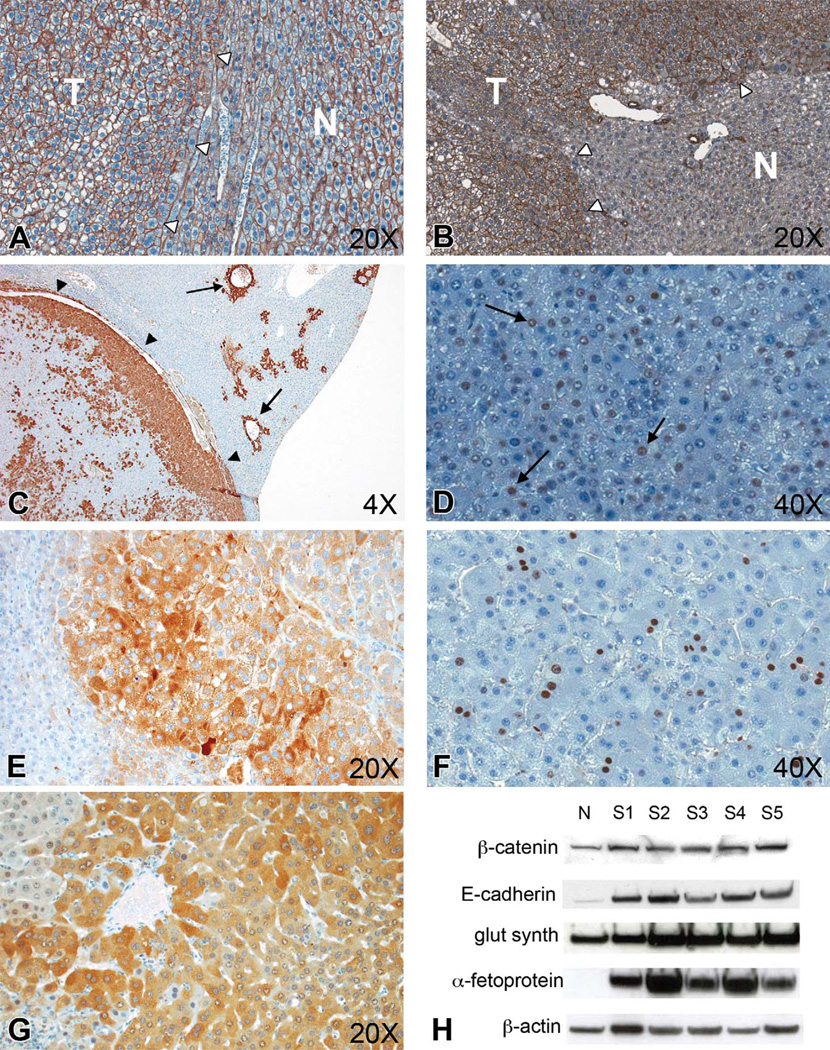

Protein expression by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry was used as another method to validate the gene expression changes observed on microarray analysis (Figure 8). By immunohistochemistry, β-catenin (CTNNB1) expression was not appreciably increased (Figure 8A), nor was there evidence of nuclear translocation of the protein. However, there was an increase in cytoplasmic and membrane expression of E-cadherin (CDH1; Figure 8B) in spontaneous tumors. Furthermore, there was a diffuse increase in cytoplasmic expression of glutamine synthetase in spontaneous tumors, compared to a predominantly minimal periportal distribution in normal liver (Figure 8C). Upregulation of glutamine synthetase (GLUL) is consistent with β-catenin upregulation and is often used as a marker for β-catenin overexpression in human HCC (Bioulac-Sage et al. 2007). Protein expression of Cyclin D (CCND1; Figure 8D, arrows) and CMYC (Figure 8E) was increased in spontaneous tumors, indicative of increased transcription resulting from Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation. KI67 expression (Figure 8F) as an indicator of cellular proliferation was increased as expected in spontaneous HCC, with absent to minimal expression in normal hepatocytes. Consistent with microarray findings of increased proliferation and disruption of normal apoptosis, there was increased cytoplasmic expression of Survivin (BIRC5), an antiapoptotic protein, in spontaneous tumors compared to normal liver (Figure 8G). Western blotting was used to more quantitatively observe changes in protein expression of β-catenin, E-cadherin, glutamine synthetase, and α-fetoprotein (Figure 8H), because of their differential expression noted by microarray and QRT-PCR analyses. An increase in β-catenin protein expression, not appreciable by immunohistochemistry, was observed by Western blotting in spontaneous tumors. Furthermore, E-cadherin, glutamine synthetase, and α-fetoprotein were upregulated compared to normal liver, consistent with immunohistochemistry, microarray, and QRT-PCR findings.

Figure 8.

Protein expression validation by immunohistochemistry and Western blotting for important mediators involved in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development. (A)Membrane immunolabeling for β-catenin in tumor (T, white arrowheads) and adjacent normal liver parenchyma (N), hematoxylin counterstain, 20×. (B) Increased cytoplasmic and membrane immunolabeling for E-cadherin antibody in tumor tissue (T, white arrowheads) compared to adjacent normal liver (N), hematoxylin counterstain, 20×. (C) Increased Glutamine synthetase immunolabeling within tumor tissue (arrowheads) compared to centrilobular localization in normal adjacent liver (arrows), hematoxylin counterstain, 4×. (D) Increased nuclear Cyclin D immunolabeling in tumor tissue (arrows), hematoxylin counterstain, 40×. (E) Increased cytoplasmic c-Myc, hematoxylin counterstain, 20×. (F) increased nuclear Ki67, hematoxylin counterstain, 40×. (G) increased cytoplasmic Birc5 immunolabeling in tumor tissue, hematoxylin counterstain, 20×. (H) Western blot of normal liver (N) and spontaneous HCC (S1–5). There is increased protein expression of β-catenin, E-cadherin, Glutamine synthetase, and α-fetoprotein in spontaneous HCC compared to normal liver (β-actin loading control).

Discussion

Fetal/Developmental Oncogenes

Fetal reprogramming, or re-expression of developmental oncogenes, is a well-recognized process that occurs in several different types of human cancer. Several of the top upregulated genes identified in this dataset include fetal genes (Figure 5 and Table 3) that are re-expressed in human HCC or other human cancers. For example, α-fetoprotein (Afp) is widely considered as a biomarker for the detection and progression of human HCC (Izumi et al. 1992). Overexpressed in 70 to 80% of HCC, its protein product is produced by the fetal liver; it rapidly decreases in concentration following birth and is not present in the adult liver (Chan et al. 2009). In our dataset, Afp was upregulated almost 440-fold by microarray and almost 1,200-fold increased by RT-PCR. H19, Another fetal oncogene, is upregulated in human HCC and is under the same regulatory control as Afp (Ariel et al. 1998). H19 was upregulated close to 92-fold compared to normal liver on the microarray. Brain expressed X-linked gene 1 (Bex1), an embryonic gene expressed in the developing human central nervous system, pancreas, ovary, testes, and other organs (Braeuning et al. 2006), was markedly upregulated over 242-fold compared to normal liver. Recently, Bex1 was shown to be overexpressed in mouse liver tumors harboring Ctnnb1 and H-ras mutations (Braeuning et al. 2006). Glypican 3 (Gpc3) is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that functions as a coreceptor for several mediators in cellular growth and proliferation pathways including the Wnt pathway, where it facilitates the interaction of Wnt mediators with their receptors (Capurro et al. 2005; Kandil and Cooper 2009). It has been used as a marker of HCC in humans and is not expressed in normal liver or benign liver lesions (Capurro et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2006). Similarly, Gpc3 was upregulated almost 37-fold by array and over 1,300-fold by RT-PCR compared to normal liver in spontaneous mouse HCC.

Stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 2 (Scd2) is expressed at high levels in embryonic liver (Griffitts et al. 2009; Miyazaki et al. 2005), and has also been shown to be important in the biosynthesis of lipid in mouse skin and liver during development (Miyazaki et al. 2005). Scd2 was overexpressed over 20-fold in spontaneous HCC in our study and was previously reported as overexpressed in HCC from a Tgf-α/c-Myc transgenic mouse model of HCC (Griffitts et al. 2009). Bmi1 is an epigenetic regulator of gene transcription responsible for embryonic development through chromatin modification. It was first discovered as a cooperating oncogene with c-Myc in a transgenic mouse model of B-cell lymphoma as a result of retroviral insertional mutagenesis (Haupt et al. 1991), and since then it has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several types of human cancer, including lymphoma (Haupt et al. 1993), brain (Leung et al. 2004), lung (Vonlanthen et al. 2001), liver (Neo et al. 2004), and breast cancer (Dimri et al. 2002; Hoenerhoff et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2004), among others. It has been shown to promote the growth and proliferation of human mammary epithelial cells in vitro, and to promote the transformation to malignant phenotype in xenograft models in collaboration with H-Ras (Datta et al. 2007; Hoenerhoff et al. 2009). Overexpression (or re-expression) of fetal genes plays a significant role in the reactivation of fetal growth pathways in HCC, resulting in increased proliferation and dedifferentiation.

Protooncogenes

Dysregulation of several protooncogenes was observed in our microarray analysis of spontaneous HCC in B6C3F1 mice (Figure 5 and Table 3). c-Fos and c-Jun are protooncogenes in the AP1 family of transcription factors, which play important roles in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, differentiation, and transformation (Guller et al. 2008; Yuen et al. 2001). The protein product of the c-Fos protooncogene is expressed in a large percentage of human HCC, whereas it is absent in normal liver. In one study, out of 150 human HCC, up to 91% of the tumors expressed C-FOS protein compared to 0% of normal liver samples (Yuen et al. 2001); a second report found no expression in normal liver samples, increased expression in liver parenchyma adjacent to HCC, and the highest expression of C-FOS in HCC by immunohistochemistry (Feng et al. 2001). Similarly, c-Fos expression in normal liver of B6C3F1 mice is undetectable (Tao et al. 1999), but it is significantly upregulated in spontaneous HCC according to our array data. This protein is associated with all phases of the cell cycle and increases proliferation of human hepatocytes in part by stabilizing nuclear Cyclin D, which is associated with cell cycle progression (Feng et al. 2001; Guller et al. 2008). Consistent with this description, the expression of several cell cycle mediators, including Cyclin D, was upregulated in spontaneous HCC in our study.

c-Jun is a transforming protooncogene that interacts directly with DNA to promote gene expression. It has been associated with several aggressive cancers in humans including sarcomas (Mariani et al. 2007), mesothelioma (Taniguchi et al. 2007), leukemia (Rangatia et al. 2003), and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Mathas et al. 2002). c-Jun has been implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis in a genetically modified mouse model of HCC (Eferl et al. 2003), and expression of both c-Jun and c-Fos mRNA is upregulated by AFP in a human HCC cell line (Li et al. 2004). Furthermore, in mice it has been shown that deletion of c-Jun expression leads to impaired post-natal hepatocellular proliferation and regeneration (Behrens et al. 2002) through repression of p53/p21 and p38 MAPK activity (Stepniak et al. 2006), indicating that it is an important mediator of hepatocellular proliferation and survival.

c-Myc was upregulated close to five-fold in spontaneous mouse HCC compared to normal liver by QRT-PCR. c-Myc is an important oncogene whose expression is associated with cell proliferation, differentiation, and cancer in humans (Popescu and Zimonjic 2002; Wu et al. 1999), and whose overexpression is associated with both mouse (Calvisi and Thorgeirsson 2005; Murakami et al. 1993) and human HCC (Popescu and Zimonjic 2002; Shachaf et al. 2004). Furthermore, its amplification has been associated with malignant conversion from preneoplastic lesions to early HCC (Kaposi-Novak et al. 2009). Although c-Myc was not upregulated on the array, its expression was evaluated owing to the significant involvement of this oncogene in human cancer, and more specifically, human HCC. The statistical methods used to analyze this dataset ensure the most stringent analysis to prevent error and minimize the false discovery rate, and while controlling for error rates, this gene may have been lost as a false negative.

Tumor Suppressor Genes

Downregulation of tumor suppressor genes is a common mechanism during tumorigenesis, through loss of gene expression because of genetic mutation, allelic loss (loss of heterozygosity, LOH), or epigenetic mechanisms such as hypermethylation. In this study, several tumor suppressor genes were downregulated in HCC compared to normal liver (Figure 5 and Table 3). PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) binds to and inhibits the function of PIP3 and AKT/PKB, which are responsible for proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis. Downregulation of PTEN expression is associated with increased tumor grade, advanced disease stage, and poor prognosis in human HCC (Hu et al. 2007; Wang, Wang et al. 2007). Growth arrest specific-1 (GAS1) is a tumor suppressor gene that plays a role in growth suppression. GAS1 protein prevents normal and neoplastic cell cycling by blocking entry from G(0) to S phase transition, and its downregulation is thought to be involved in the promotion of proliferation (Martinelli and Fan 2007). GAS1 is suppressed by MYC and SRC signaling, and multiple gene expression profiling experiments have noted downregulation of GAS1 during carcinogenesis (Huang et al. 2001; Lapouge et al. 2005). In addition, overexpression of GAS1 has been shown to slow the growth of human glioma cells in vitro (Zamorano et al. 2004), as well as human pulmonary adenocarcinoma growth in xenografted nude mice in vivo (Evdokiou and Cowled 1998), indicating that GAS1 has functional importance as a tumor suppressor, and that loss or downregulation can contribute to carcinogenesis. WWOX (WW-domain containing oxidoreductase) is a tumor suppressor gene that has been implicated in multiple types of human cancer through homozygous deletion, point mutation, and promoter methylation (Aderca et al. 2008), and is frequently downregulated in human HCC (Park et al. 2004). It functions in p53-mediated apoptosis (Chang et al. 2005), and its downregulation causes increased cell proliferation in HCC cell lines (Aderca et al. 2008).

Cell Cycle Regulation

Several genes associated with cell cycle progression were overexpressed in spontaneous mouse HCC, including G1/S and G2/M checkpoint mediators (Figure 6 and Table 3). As discussed above, c-Fos overexpression stabilizes nuclear Cyclin D during G1/S (Guller et al. 2008), and a concordant upregulation of Cyclin D mRNA expression is present in spontaneous tumors. Cyclin D is also a downstream target of transcription of the Wnt signaling pathway and β-catenin overexpression, as seen in spontaneous tumors in this study (discussed below). Consistent with this description, nuclear expression of Cyclin D protein was observed in spontaneous HCC by immunohistochemistry (Figure 8D). Cyclin D1 complexes with Cdk4/6 to phosphorylate Rb and activate transcription of downstream S phase genes, promoting the cell cycle. Conversely, p15 (Cdkn2b) is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) that functions to inhibit the association of Cyclin D1 with Cdk4/6 and cause cell cycle arrest. Cyclin A promotes cell cycle progression by complexing with Cdk1 or Cdk2 during S phase into G2, and it is also regulated by β-catenin signaling during hepatocarcinogenesis (Wang et al. 2009).

Among upregulated G2/M cell cycle checkpoint mediators in spontaneous tumors, cyclin B associates with Cdk1 during G2/M checkpoint transition and entry into mitosis. Cdk7 encodes for a CDK-activating kinase that is required for the activation of Cdk2/cyclin complexes and promotion of S phase, as well as Cdk1/cyclin B assembly and entry into mitosis (Larochelle et al. 2007).

Other genes upregulated in spontaneous tumors that are associated with cell cycle progression included Ki67, Mcm6, Aurka, and Mad211. KI67 encodes for a nuclear protein associated with cellular proliferation, has been closely associated with growth rate in human HCC, and is used as a prognostic marker indirectly associated with survival and disease-free interval (Stroescu et al. 2008). Minichromosome maintenance complex component proteins (MCM4–7) are DNA helicases that are critical for the initiation of genomic replication and function to unwind DNA during the cell cycle. Phosphorylation of MCM4 by CDK1 is necessary for chromatin binding during M phase, and phosphorylation by CDK2 is required during interphase (Komamura-Kohno et al. 2006). These proteins play roles in initiation and elongation during DNA replication (Masai et al. 2006).

Aurora kinase A (AURKA) is important for appropriate chromosome segregation, and overexpression of AURKA has been reported in several human cancers, including HCC, in which it is associated with high tumor grade and stage (Jeng et al. 2004). MAD2L1 plays a central role in the mitotic checkpoint and is overexpressed in several types of cancer in humans. It is overexpressed both at the mRNA and protein levels in dysplastic liver nodules and HCC, with a tendency to be overexpressed to a greater extent with increasing malignancy, suggesting a role in progression of the neoplasm in humans (Zhang et al. 2008).

Transcription Factors

Upregulation of several transcription factors associated with downstream cellular proliferation signaling (Tcf-Lef, Tcf1/3/4, Tcf12, Tcf19, Top2a, and Ets2) was observed in spontaneous mouse HCC. The Tcf-Lef transcription factors play a major role in downstream signaling in the Wnt/β-catenin growth pathway. Binding of Tcf-Lef transcription factors to β-catenin in the nucleus results in the transcription of numerous downstream genes that are involved in cellular proliferation in human HCC (Giles et al. 2003). TOP2A (topoisomerase 2a) encodes for an enzyme that alters DNA structure to facilitate transcription. Overexpression of this gene in humans has been associated with drug resistance to certain cancer therapeutics (Pang et al. 2005), and when overexpressed in HCC, it has been associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype and recurrence (Watanuki et al. 2002). ETS transcription factors, including ETS2, are involved in numerous cellular processes including stem cell regulation, cellular senescence and apoptosis, and tumorigenesis. Additionally, ETS1 induces transcription of several matrix metalloproteinase genes in human HCC, which are implicated in the progression and biologic behavior of this tumor (Ozaki et al. 2003)

Growth Pathways

Multiple genes encoding growth factor proteins have been implicated in the progression of human HCC. Several of these mediators were dysregulated in spontaneous mouse HCC compared to normal liver (Table 1). One commonly dysregulated pathway in human and mouse HCC is the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Genetic alterations of genes in the Wnt signaling pathway are frequently found in human HCC (Kim et al. 2008), including mutations in exon 3 of CTNNB1, resulting in overexpression and nuclear translocation of the β-catenin protein. Consistent with this process, expression of Ctnnb1, the gene encoding for mouse β-catenin, was overexpressed in spontaneous mouse HCC, along with α- and δ-catenins. Overexpression of β-catenin is associated with downstream signaling and transcriptional activation of target genes such as Ccnd, c-Jun, Egfr, and Cdh1 (E-cadherin; Anna et al. 2003), which are also overexpressed in spontaneous mouse HCC.

Trefoil factor 3 (Tff3) was upregulated close to 45-fold by array and close to 500-fold by RTPCR compared to normal liver. Tff3 is commonly overexpressed in chemically induced mouse models of HCC, and often in human HCC as a result of promoter hypomethylation (Khoury et al. 2005; Okada et al. 2005). TFF3 overexpression is also reported in other human cancers, including gastric (Leung et al. 2000) and skin carcinoma (Hanby et al. 1998), papillary-mucinous tumor in the pancreas (Terris et al. 2002), and breast cancer (May and Westley 1997), and it is thought to induce cancer cell growth by perturbing complexes between E-cadherin, β-catenin, and other associated proteins (Efstathiou et al. 1998). Likewise, tetraspanin 8 (Tspan8), a member of the transmembrane-4 superfamily of cell surface proteins that mediate cell–cell junctions with integrins, was upregulated close to 200-fold on the microarray, and over 250-fold by RT-PCR, compared to normal liver. It is overexpressed in several human cancers (gastric, colon, rectal, pancreatic; Zoller 2009), as well as HCC (Kanetaka et al. 2001), and overexpression of TSPAN8 has been correlated with poor tumor differentiation and intrahepatic metastasis (Kanetaka et al. 2003; Kanetaka et al. 2001). Conflicting reports exist about the expression of E-cadherin (CDH1) protein in human HCC; although most literature reports that loss of CDH1 expression is a common event in human HCC, Osada et al. (1996) showed that human HCC cells lacking CDH1 expression failed to induce intrahepatic metastases in xenografted nude mice, whereas HCC cells expressing CDH1 were metastatic.

The NFκB pathway is involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and various immune and inflammatory responses (Rayet and Gelinas 1999), and upregulation of Nfκb gene family members Nfκb1 and Nfκb2 was observed in spontaneous mouse HCC. Overexpression of NFκB family members has been observed in various hematopoietic and solid human neoplasms (Rayet and Gelinas 1999), including overexpression of NFκB1 in lung, colon, prostate, breast, bone, and brain tumors (Mukhopadhyay et al. 1995), and overexpression of NFκB2 in breast and colon carcinomas (Bours et al. 1994; Dejardin et al. 1995).

Upregulation of the Tgfβ canonical pathway and Tgfβ family members (Tgfβr2, Smad3, Tgif1, and Tgfα) was observed in spontaneous mouse HCC. TGFβ has been implicated in a number of human malignancies, where it plays a dual role; it acts primarily as a tumor suppressor early in carcinogenesis, and as a promoter later in the progression of the disease (Coulouarn et al. 2008). RhoC, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases, was also overexpressed in spontaneous mouse HCC. This mediator has been shown in human HCC to be associated with the assembly of focal adhesion complexes that lead to proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells in human HCC (Wang, Yang et al. 2007). Overexpression of RhoC mRNA is present in human HCC samples, with increasing levels in metastatic lesions, and there is a significant relationship between RhoC expression and decreased cellular differentiation, vascular invasion, and regional and distant metastasis (Wang et al. 2003).

There was upregulation of several genes encoding for effectors of the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway (Shp2, Stat6, Ptpn11, Pias), important in growth factor- and cytokine-mediated stimulation of cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and differentiation (Rawlings et al. 2004), as well as inhibitors of STAT signaling such as protein tyrosine phosphatase (Ptpn11) and protein inhibitor of activated stats (Pias). The cellular processes involved in JAK/STAT signaling are numerous and varied; in fact, JAK/STAT signaling may influence other growth signaling pathways, including the Ras-MAPK, PI3K-AKT, and Src-kinase cascades leading to cellular growth and proliferation, and overexpression of JAK/STAT signaling has been implicated in tumorigenesis (Rane and Reddy 2000).

Apoptosis Regulators

The balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic mediators plays a significant role in the proliferation of cell populations. The Bc12 family of apoptosis mediators regulates cell death and is associated with the progression of several types of cancer (Guo et al. 2002). Several pro- and anti-apoptotic members of the Bc12 family were upregulated in spontaneous mouse HCC compared to normal liver (Table 3). Apoptosis antagonists that were upregulated included Bc12 and Bc1211 (Bcl-Xl). RNA and protein expression of another anti-apoptosis gene, Birc5 (Survivin), was upregulated in spontaneous mouse HCC; this gene encodes for a protein that functions as a key regulator of cell proliferation, and its overexpression has been implicated in several human cancers including liver cancer (Peroukides et al. 2010). In combination with the proliferative effects resulting from overexpression of proto-oncogenes, the expression of anti-apoptotic mediators such as Bc12 and Bc1211 (Bcl-Xl) can prevent apoptosis, even in the face of growth factor depletion.

Since both proliferation and apoptosis are ongoing events in cancer, the balance between these mediators is an important factor in the progression of the disease. Since apoptosis is rare in normal liver, HCC tissues generally have increased rates of apoptosis compared to normal liver (Guo et al. 2002). Therefore, it is not surprising to find upregulation of pro-apoptotic mediators in HCC in contrast to other types of cancer, in which apoptosis may be predominantly inhibited. There was upregulation of several genes encoding apoptosis agonists in spontaneous mouse HCC, including the pro-apoptotic Bc12 family members Bax, Bc12111 (Bim), and Bc110, as well as Apaf1 and Casp1, 4, and 12. Several isoforms of Bim are upregulated in human HCC and may influence tumor cell growth and sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs (Miao et al. 2007). APAF-1 protein is bound by BCL2 on the outer mitochondrial membrane, and as a result of death agonists, it is released into the cytosol, and activates initiator caspases. CASP1, one such initiator caspase, causes release of cytochrome C through activation of BAX (Thalappilly et al. 2006). BAX activation results in activation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–associated CASP4 (CASP12 in mice) through an ER stress–mediated response (Hitomi et al. 2004). Several of the apoptosis genes upregulated in this dataset, including caspases 1, 4, and 7, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily members, and mitochondrial associated cell death pathways (Bc12, Bax) have been shown to be upregulated in active cirrhosis associated with HCC in humans (Zindy et al. 2005). From these data, it is clear that both pro- and anti-apoptotic signaling pathways are at play in spontaneous HCC, and the balance between these mediators dictates the degree of cell proliferation and apoptosis in HCC.

DNA Damage Repair Genes

Dysregulation of the DNA damage repair process is frequently observed in neoplasia and is one of several significantly upregulated canonical pathways in mouse and human HCC. The DNA damage repair response involves multiple events designed to stop the cell cycle, to prevent the inheritance of DNA mutations to cell progeny, stimulate DNA repair machinery at sites of damage, and either resume the cell cycle once damage is repaired, or induce apoptosis should repair be impossible (Darzynkiewicz et al. 2009). Several mediators of DNA damage repair were upregulated in spontaneous mouse HCC, including Brca1, Rad51, Rad52, Msh2, Msh6, and Xrcc5 (Table 1).

BRCA1 is responsible for normal DNA double-strand break repair, and individuals who harbor mutations in BRCA1 are predisposed to developing breast and ovarian tumors (West 2003). RAD51 and RAD52 genes encode for DNA recombinase enzymes that are responsible for initiating repair of double-stranded DNA breaks through interaction with BRCA1 and 2 (West 2003), and XRCC gene proteins are involved in the repair of double-strand DNA breaks through non-homologous end joining to prevent genomic instability, a prelude to carcinogenesis (Thacker and Zdzienicka 2004). MSH2 and MSH6 are mismatch repair enzymes that correct microsatellite instability, and inactivating mutations of mismatch repair enzymes have been reported in various cancers including gastric, colorectal, and endometrial tumors (Wang et al. 2001).

Angiogenic Factors and Extracellular Matrix Proteins

In human HCC, increased angiogenesis and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and remodeling frequently accompany chronic inflammatory changes, ongoing hepatocellular damage and necrosis, and cirrhosis that precede tumorigenesis. Genes encoding ECM proteins (Sparc, Mmp14) and proangiogenic factors (Vegf, Pdgf-a) were upregulated in spontaneous mouse HCC (Table 3), similar to the expression observed in cases of human HCC. In human HCC, upregulation of MMP14 is associated with intrahepatic metastasis and vascular invasion, and increased expression correlates with a poor patient outcome (Ip et al. 2007). SPARC is a glycoprotein that is associated with remodeling of the ECM. It is highly expressed in the stroma of HCC in humans and plays a role in cell adhesion, differentiation, and proliferation (Le Bail et al. 1999). Vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C) is an important pro-angiogenic mediator that induces the development and proliferation of new blood and lymph vessels within tumors, and its expression is related to biologic progression and metastasis of human HCC (Yamaguchi et al. 2006). Similarly, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) promotes vascularization of tumors and ECM remodeling, and abnormal expression of PDGF ligands and receptors has been reported in human HCC (Fischer et al. 2007). In particular, Fischer et al. (2007) found that PDGF-A is upregulated by TGF-β expression, a promoter of tumorigenesis in advanced-stage human HCC. Increased expression of both Pdgf-a and Tgf-β was found in spontaneous mouse HCC.

Major Downregulated Pathways in Human and Mouse HCC

The most significant genes and canonical pathways similarly downregulated between mouse and human HCC included fatty acid metabolism, tryptophan metabolism, xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, and bile acid metabolism (Table 2). The liver is responsible for the uptake, storage, and release of lipids into the circulation, the production of various amino acids, and the use of numerous biochemical pathways in the metabolism of various byproducts and xenobiotics. Numerous mediators tightly regulate these processes, and disruption of normal cellular signaling and molecular transport during tumorigenesis can lead to abnormal tissue homeostasis and aberrant or loss of cell signaling.

Several of the most downregulated genes in spontaneous mouse HCC encode for metabolic enzymes and factors involved in normal organ function and tissue homeostasis (Table 4), including genes encoding for several cytochrome P450 enzymes, including Cyp8b1 and Cyp2c19. Cytochrome P450 proteins function in catalyzation of reactions involved in drug metabolism, and synthesis of cholesterol, steroids, and other lipids. CYP8B1 is one of many enzymes involved in bile acid synthesis (Wang et al. 2005), and its downregulation in HCC illustrates the marked dysregulation of cellular processes in tumorous tissue compared to normal hepatocytes. Interestingly, Wu and colleagues (2006) found that CYP2C19 mRNA was significantly elevated in HCC compared to normal adjacent liver parenchyma, and absent in other tissues and cancers. However, downregulation of this enzyme in spontaneous murine HCC may represent dysfunction of normal liver metabolism, rather than a direct mediator related to carcinogenesis.

Elov13 belongs to a family of genes that are involved in the production of very long chain fatty acids (Brolinson et al. 2008), and its marked downregulation in spontaneous HCC may represent loss of normal hepatocelluar function resulting from tumorigenesis rather than a direct result of oncogenic signaling. Similarly, carbonic anhydrase III (Ca3) and Hamp, genes encoding for mediators responsible for aspects of normal hepatic function, were similarly downregulated. Ca3 is a marker of oxidative stress (Cabiscol and Levine 1995), and Hamp encodes for hepcidin, a protein integral for iron homeostasis in the liver. Hepcidin functions to maintain serum and liver iron concentrations at normal steady-state levels, and it is significantly downregulated in human HCC (Tseng et al. 2009), similar to spontaneous HCC in B6C3F1 mice in this study.

Taken together, the marked downregulation of these genes encoding for mediators associated with normal hepatocellular function and physiologic processes may likely be the result of altered hepatocellular homeostasis and loss of function rather than a primary process resulting from dysregulation of pathways associated with hepatocellular carcinogenesis.

Summary and Conclusions

We have used global gene expression profiling of spontaneous HCC from B6C3F1 mice to illustrate overrepresentation of molecular pathways important in the pathogenesis of human HCC. These pathways include those involved in development/fetal reprogramming (fetal oncogenes), cell growth and proliferation (protoconcogenes, growth factors, cell cycle regulation, DNA damage repair), loss of growth inhibition (tumor suppressor genes), alteration of the extracellular matrix (angiogenesis and matrix remodeling genes), and dysregulation of the balance between cell death and survival (pro- and anti-apoptotic genes). The characterization of the molecular changes occurring in spontaneous HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse model in the context of human HCC is crucial to the understanding of the utility of this model and its limitations. We have shown that global gene expression profiling enables high-throughput investigation of genome-wide changes in gene expression and the identification of dysregulated genes implicated in carcinogenesis in the NTP chronic bioassay. By using this pathway-centered approach to investigating changes in gene expression in mouse tumors, we may identify important targets relevant to human HCC. However, it is important to understand that this type of analysis affords only a snapshot in time in terms of gene expression. Targets that are identified that have potential relevance in the pathogenesis of cancer need to be further validated functionally in vitro and in vivo to establish biologic relevance to the human disease. Furthermore, future studies will evaluate early time points (precancerous) in the carcinogenic process in order to identify critical initiating events that lead to carcinogenesis in not only the liver, but other organ systems. Once early events in carcinogenesis are identified, causation may be inferred, and once functionally validated, the relevance of such targets to the human disease and risk assessment can be better evaluated. In terms of global gene expression of HCC in the B6C3F1 mouse, despite differences in etiology and pathogenesis to human HCC, the molecular readout is very similar, which provides additional support for the application of this model to the study of HCC. Furthermore, continued large-scale gene expression and pathway-based analysis of tumors as well as early time points in NTP studies will lay the groundwork for the establishment of databases of gene expression of precancerous and spontaneous neoplastic lesions. Comparing such databases with gene expression studies from preneoplastic lesions or tumors induced by chemical treatment in NTP studies may ultimately be a powerful tool for prediction of tumorigenic responses to compounds, especially in terms of early initiating events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Grace Kissling of the Biostatistics Branch, NIEHS, for assistance with statistical analysis; Laura Wharey for microarray analysis; and the NIEHS histology and immunohistochemistry departments for their assistance. This research [in part] was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

This article may be the work product of an employee or group of employees of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), however, the statements, opinions or conclusions contained therein do not necessarily represent the statements, opinions or conclusions of NIEHS, NIH, or the United States government.

References

- Aderca I, Moser CD, Veerasamy M, Bani-Hani AH, Bonilla-Guerrero R, Ahmed K, Shire A, Cazanave SC, Montoya DP, Mettler TA, Burgart LJ, Nagorney DM, Thibodeau SN, Cunningham JM, Lai JP, Roberts LR. The JNK inhibitor SP600129enhances apoptosis of HCC cells induced by the tumor suppressor WWOX. J Hepatol. 2008;49:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anna CH, Iida M, Sills RC, Devereux TR. Expression of potential beta-catenin targets, cyclin D1, c-Jun, c-Myc, E-cadherin, and EGFR in chemically induced hepatocellular neoplasms from B6C3F1 mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;190:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariel I, Miao HQ, Ji XR, Schneider T, Roll D, de Groot N, Hochberg A, Ayesh S. Imprinted H19 oncofetal RNA is a candidate tumour marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Pathol. 1998;51:21–25. doi: 10.1136/mp.51.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A, Sibilia M, David JP, Mohle-Steinlein U, Tronche F, Schutz G, Wagner EF. Impaired postnatal hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration in mice lacking c-jun in the liver. EMBO J. 2002;21:1782–1790. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bioulac-Sage P, Rebouissou S, Thomas C, Blanc JF, Saric J, Sa Cunha A, Rullier A, Cubel G, Couchy G, Imbeaud S, Balabaud C, Zucman-Rossi J. Hepatocellular adenoma subtype classification using molecular markers and immunohistochemistry. Hepatology. 2007;46:740–748. doi: 10.1002/hep.21743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bours V, Dejardin E, Goujon-Letawe F, Merville MP, Castronovo V. The NF-kappa B transcription factor and cancer: High expression of NF-kappa B- and I kappa B-related proteins in tumor cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braeuning A, Jaworski M, Schwarz M, Kohle C. Rex3 (reduced in expression 3) as a new tumor marker in mouse hepatocarcinogenesis. Toxicology. 2006;227:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brolinson A, Fourcade S, Jakobsson A, Pujol A, Jacobsson A. Steroid hormones control circadian Elov13 expression in mouse liver. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3158–3166. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann A, Karcier Z, Schmid B, Strathmann J, Schwarz M. Differential selection for B-raf and Ha-ras mutated liver tumors in mice with high and low susceptibility to hepatocarcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2008;638:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabibbo G, Craxi A. Epidemiology, risk factors and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabiscol E, Levine RL. Carbonic anhydrase III. Oxidative modification in vivo and loss of phosphatase activity during aging. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14742–14747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvisi DF, Thorgeirsson SS. Molecular mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mouse models of liver cancer. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33:181–184. doi: 10.1080/01926230590522095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]