Abstract

Extensive research defines the impact of advanced maternal age on couples’ fecundity and reproductive outcomes, but significantly less research has been focused on understanding the impact of advanced paternal age. Yet it is increasingly common for couples at advanced ages to conceive children. Limited research suggests that the importance of paternal age is significantly less than that of maternal age, but advanced age of the father is implicated in a variety of conditions affecting the offspring. This review examines three aspects of advanced paternal age: the potential problems with conception and pregnancy that couples with advanced paternal age may encounter, the concept of discussing a limit to paternal age in a clinical setting, and the risks of diseases associated with advanced paternal age. As paternal age increases, it presents no absolute barrier to conception, but it does present greater risks and complications. The current body of knowledge does not justify dissuading older men from trying to initiate a pregnancy, but the medical community must do a better job of communicating to couples the current understanding of the risks of conception with advanced paternal age.

Keywords: Male infertility, genetics

In recent years, advanced paternal age has become an increasingly significant concern as men and women delay starting families. Pregnancy outcomes related to maternal age include low birth weight, premature birth, and pregnancy loss (1), as well as any number of risks of birth defects after parturition. It has also been shown that the rate of chromosomal abnormalities increases exponentially in the offspring of women over the age of 35 (2). The effects of advanced maternal age are better understood than the effects of paternal age. Although rarely discussed with patients, advanced parental age presents risks to offspring by increasing the chances of introducing genetic abnormalities that may lead to the emergence of serious diseases or birth defects.

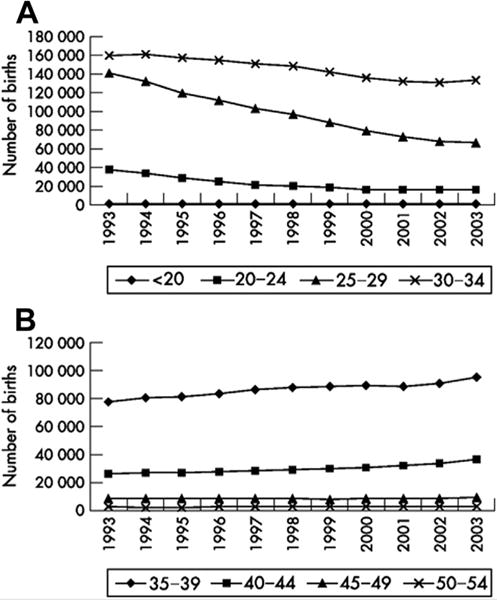

Although there is a trend toward increasing average age at which men father children (Fig. 1) (3), the nature and effects of advanced paternal age are less studied, but the literature suggests that paternal age presents serious problems to the couple seeking to conceive a child. Advanced paternal age is associated with declines in the motility and morphology of spermatozoa, as well as in the rate of pregnancy and incidence of pregnancy loss, which compounds the effect of advanced maternal age on this outcome. In a study evaluating donor assisted reproductive technology cycles, advanced paternal age negatively impacts embryo development and reproductive outcome (4). Advanced paternal age also increases the relative risk of offspring developing conditions such as neurocognitive defects, some forms of cancers, and syndromes related to aneuploidies. Physicians and their patients must be better informed of the risks and problems associated with advanced paternal age, but discussion with older couples seeking to conceive is confounded by the lack of a clear definition of this condition. The age of 35 is a discrete time point after which risks of adverse reproductive outcome are significantly increased for women, but there is no consensus on the existence or identity of such a time point for men.

FIGURE 1.

Trends in paternal age for live births within marriage in England and Wales, 1993–2003. (A) decreasing trends <35 years. (B) increasing trends 35–54 years. Source: Series FM1 no 32 (ONS, 2003). (Births to fathers over 54 years old account for less than 0.5% of live births within marriages and are not shown). Reproduced with permission from reference (3).

This review seeks to summarize the problems couples with an older male partner may encounter in attempting to conceive and the risks to offspring that arise with advanced paternal age, as well as the disagreement among clinicians of how to define advanced paternal age.

Barriers to Conception with Advanced Paternal Age

The impact of male age on fecundity remains controversial. A large population study, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood, investigated the effect of paternal age on time to conception (5). Compared with men <25 years old, the adjusted odds ratio for conception in ≥12 months was 0.5 in men ≥35 years of age, meaning that men older than 35 had a 50% lower chance of conceiving within 12 months than men <25 years of age, even after adjusted for maternal age. Admittedly, this conclusion is based on the conditional probability of conception within 6 or 12 months in couples who ultimately had a baby. This conclusion does not necessarily reflect the probability of conception in the population as a whole. Nevertheless, time to conception can provide a useful index of fecundity.

Several hormonal changes occur as a result of aging. T and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) were measured in stored samples from 890 men in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (6). After compensating for date effects, the investigators observed significant, independent, age-invariant, longitudinal effects of age on both free and total T. There was a steady decline in both concentrations together with increasing male age, accompanied by an increase in SHBG. Incidence of low T (<300 ng/dL) progressively increased to about 20% in men over 60, 30% in those over 70, and 50% in those over 80 years of age (6). The decline in total and free T contributes to decreased libido and frequency of intercourse, impaired erectile function (7), and poor semen quality (8), all factors that may lead to decreased fecundity.

Several morphological changes that occur in testis histology and changes that occur in semen parameters with advanced age suggest evidence of deteriorating testicular function. The number of Leydig cells (9), Sertoli cells (10), and germ cells decreases with age (11). Semen analyses show a noticeable decrease in semen volume, sperm motility, and sperm morphology as men get older. Reports of the effect of advanced age on sperm density are inconsistent throughout the literature (8).

Spermatozoa from older men display less fertilizing potential after donor insemination (12), IUI (13), or IVF (14). One factor that might contribute to worse outcomes using assisted reproduction is increased DNA fragmentation. Several studies show that DNA fragmentation increases with male age (15, 16). In fact, in men between 60 and 80 years of age, the percentage of DNA fragmentation in ejaculated sperm is estimated to be 88% (15). A DNA fragmentation index above 30% is considered to be abnormal in most laboratories and potentially could be associated with less favorable outcomes with assisted reproduction (17). Both antioxidants (18) and varicocele repair were reported to decrease the probability of sperm DNA fragmentation (19), although from an evidenced-based medicine perspective many studies of significant sperm DNA fragmentation, in general, are conflicting and controversial.

Unfortunately, mature couples have an increased risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery. In a large retrospective population-based study of women aged 25–44 years in Denmark, Germany, Italy, and Spain (20), after adjustment for various factors (e.g., reproductive history, country), the investigators found that the risk of miscarriage was higher if the woman was ≥35 years old (as previously reported in a number of studies). However, the increase in risk was much greater for couples composed of a woman ≥35 years and a man ≥40 years. An association between paternal age and fetal loss strengthens the idea that paternal age influences the health of offspring via mutations of paternal origin. In another large prospective study of 23,821 pregnant women followed in the Danish National Birth Cohort study from 1997 to 1999 (21), pregnancies initiated by men 50 or older had a twofold increased risk of ending in fetal loss. This resulted in half the incidence of successful pregnancies initiated by younger fathers (after adjustment for maternal age, reproductive history, and maternal lifestyle during pregnancy). Taken together, these observations support the conclusion that the effects of paternal age on a couple’s fecundity cannot be disregarded.

Is There a Specific Age Threshold after Which Physicians Should Counsel Couples Regarding the Implications of Advanced Paternal Age on Outcomes?

Currently, in the absence of a clear definition, it is difficult for clinicians to engage patients in a meaningful discussion of advanced paternal age. Because aging is a highly complex and incompletely understood process that affects individuals differently, clinicians have difficulty generalizing information about the complex effects of aging across a population. Currently, the American College of Medical Genetics does not specify an upper age limit for men who are seeking to initiate a pregnancy (22). To better counsel patients, clinicians must develop a clearer understanding of the way in which paternal age affects reproductive outcomes.

Clear agreement expressed about a discrete, recommended cutoff point for paternal age is lacking in the medical literature. A search of Medline and Embase databases from 2008 to December 2014 using the search term “advanced paternal age” revealed just 62 published studies. Of these, approximately half of the papers defined different thresholds for advanced paternal age, and half did not (Supplemental Table 1). The latter category of studies treated paternal age either as a continuous variable or as a categorical variable, most commonly stratified into age brackets of 5 years (e.g., 35–39, 40–44, etc.). Generally, studies that used a threshold age divided their sample populations on the basis of paternal age and then sought to determine whether there was a correlation with a birth defect. In contrast, studies that did not have a threshold age examined a case and controlled population and then analyzed the paternal ages of each group to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference.

Even among those studies using a discrete threshold, there was a wide variation in that threshold. Just 32 of 62 studies defined an age threshold. Five studies defined the threshold as ≥30 years, two defined it as ≥32 years, nine defined it as ≥35 years, 14 (a plurality) defined it as ≥40 years, and one study each defined it as ≥45 or 50 years. While the age of 40 years was used as a threshold more than any other age, the number of studies was not so great as to imply an overwhelming consensus.

Defining advanced paternal age is further complicated by the facts that this condition can have a wide range of effects on offspring and the assorted risks of aging do not necessarily simultaneously increase. What provides a suitable definition of advanced paternal age for risk of developing certain cancers in offspring may not be a suitable definition for predicting the risk of schizophrenia or related conditions in offspring, for example. Indeed, in the more complex conditions reported in offspring, such as schizophrenia or autism spectrum disorders, there are wide ranges and varieties of symptoms reported relative to paternal age. One study by Rosenfield et al. (23) reported using a threshold of 35 years to analyze the risks of schizophrenia associated with paternal age, while a study by Torrey et al. analyzed their patient population using three different cutoffs (35, 45, and 55 years) and found that only the 55-year cutoff produced a statistically significant result (24).

Eskenazi et al. analyzed semen parameters of men at various ages in an attempt to determine a definition of the threshold at which paternal age presents increased risks to offspring. They found that semen parameters, specifically total count, motility, and sperm morphology, all declined continuously with age, with no meaningful point at which risk suddenly increased (25). Their findings corroborated those studies we reviewed that did not use a threshold at all. The reproductive medical community must determine how we will define advanced paternal age to better counsel patients about the risks involved for the offspring.

Diseases Associated with Advanced Paternal Age

In contrast to menopause, which marks the cessation of ovarian function due to the inevitable loss of female gametes, spermatogenesis continues throughout life. Nevertheless, male aging does exert detrimental effects on reproductive organs and tissues. These reported changes develop gradually without a cutoff. In women, no matter how old the mothers are, a total of 23 cell divisions are required to form mature egg cells from the zygote. In men, about 30 spermatogonial cell divisions occur before puberty. After puberty, spermatogonial stem cells divide every 16 days (~23 times per year). If the average age of male puberty is 15, sperm produced by a 70-year-old male have formed after ~1,300 mitotic divisions. DNA replication preceded each cell division, and mutations often arise as a result of uncorrected errors in DNA replication (26). Owing to the large number of cell divisions that occur during spermatogenesis, we can speculate that advanced paternal age can contribute to an increased number of de novo mutations (27). In 2012, Kong et al. published a study in which whole genome sequencing was performed on parents and children from 78 Icelandic families. This study convincingly demonstrated an association between paternal age at conception and frequency of de novo genetic mutations in offspring across the whole genome, but the relationship was especially significant in genes associated with autism spectrum disorders (27). This report has led younger men to question whether they should bank sperm while young, to prevent the risks associated with advanced paternal age. Unfortunately, no guidelines are available to direct counseling with regard to the effectiveness and safety of freshly ejaculated sperm compared with frozen samples. It is important to remember that with cryopreserved sperm, conception can only be achieved either by IUI or IVF–procedures not without risks (28).

Advanced paternal age can contribute to birth defects associated with single gene mutations and chromosomal abnormalities. Advanced paternal age is also associated with psychiatric morbidity and several malignancies. Various conditions that are associated with advanced paternal age are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Various genetic conditions in offspring that may be associated with advanced paternal age.

| Condition | Paternal age (y) | Relative risk | Population risk | Adjusted risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achondroplasia | >50 | 7.8 | 1/15,000 | 1/1,923 |

| Apert syndrome | >50 | 9.5 | 1/50,000 | 1/5,263 |

| Pfeiffer syndrome | >50 | 6 | 1/100,000 | 1/16,666 |

| Crouzon syndrome | >50 | 8 | 1/50,000 | 1/6,250 |

| Neurofibromatosis I | >50 | 3.7 | 1/3,000–1/4,000 | 1/810–1/1,080 |

| Retinoblastoma | >45 | 3 | 1/15,000–1/20,000 | 1/5,000–1/6,667 |

| Down syndrome | 40–44 | 1.37 | 1/1,200a | 1/876a |

| Klinefelter syndrome | >50 | 1.6 | 1/500 men | 1/312 men |

| Epilepsy | 40–45 | 1.3 | 1/100 | 1/77 |

| Breast cancer | >40 | 1.6 | 1/8.5 | 1/5.3 |

| Childhood leukemia | >40 | 1.14 | 1/25,000 | 1/21,930 |

| Childhood central nervous system tumor | >40 | 1.69 | 1/36,000 | 1/21,302 |

Maternal age 20–29.

Note: Adapted with permission from reference (21).

Single gene mutations

Achondroplasia was the first genetic disorder hypothesized to be influenced by paternal age (29). Achondroplasia, the most common cause of dwarfism, is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by rhizomelic limb shortening, macrocephaly, midface hypoplasia with frontal bossing, and short broad hands with a trident finger configuration. This disorder is caused by mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene (30). Similarly, mutations in the FGFR2 gene are also associated with advanced paternal age. Crouzon syndrome, Apert syndrome, and Pfeiffer syndrome are all autosomal dominant craniosynostotic disorders that can be caused by mutations in the FGFR2 gene (31). Interestingly, there is a discrepancy between the frequency of these FGFR mutations in sperm DNA and the effect of advanced paternal age on these syndromes, possibly due to selfish spermatogonial selection (32). Although harmful to embryonic development, these mutations might be paradoxically enriched because researchers suggest that they confer a selective advantage to the spermatogonial cells in which they arise (33, 34).

Mutations of the RET gene are an additional example of genetic disorders with an almost exclusively paternal origin and a significant relationship to paternal age (10). This mutation causes multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome, which typically involves the development of tumors in two or more endocrine glands. Other autosomal dominant disorders associated with advanced paternal age include neurofibromatosis I and retinoblastoma. However, increased risk of these disorders is not reported consistently in the literature (22).

Chromosomal aberrations

Numerical chromosomal aberrations are caused mainly by a nondisjunction during meiosis of the gametes, and trisomy is the most common class of the chromosomal aneuploidies. Studies of chromosomal abnormalities in human sperm show that all chromosomes are susceptible to nondisjunction, but chromosomes 21 and 22 and, especially, the sex chromosomes display an increased frequency of aneuploidy (35). Although maternal errors account for the vast majority of instances of human aneuploidy, the extra chromosome 21 is of paternal origin in approximately 10% of Down syndrome cases. Advanced paternal age significantly influences the incidence of Down syndrome when the female partner of a couple is >35 years old (36).

With regard to Klinefelter syndrome, 50% of 47,XXY cases are attributable to the male factor (16). The effect of advanced paternal age on Klinefelter syndrome is also controversial. The frequency of XY spermatozoa, which would cause a 47,XXY condition in offspring, is higher in older men than in younger men (37, 38). However, Lanfranco et al. reported that in 228 men with Klinefelter syndrome, no increased risk of conception of an affected child was found in conjunction with advanced paternal age (39). Klinefelter syndrome is incompatible with spermatogenesis (40), but it is believed that the rare foci of spermatogenesis that may be present in some Klinefelter males are actually the result of a self-correcting aneuploidy in that lineage of germ cells, allowing spermatogenesis to proceed (41). Because data about frequency of age-dependent alterations of aneuploid sperm are inconsistent in the literature (42), an association between advanced paternal age and chromosomal aneuploidy remains undetermined.

Advanced paternal age and malignancies

Advanced paternal age has a possible association with malignant diseases. A cohort study investigating all singleton live births in Northern Ireland from 1971 to 1986 (n = 434,933) showed a small but significant increase in risk of leukemia in children with advanced paternal age (43). Yip et al. also reported an increased risk of leukemia in children with advanced paternal age. Moreover, they found that the effect of paternal age was also significant for central nervous system cancers (44), a finding which is in agreement with a previous study (45). Breast cancer is also associated with advanced paternal age, even when the investigators controlled for maternal age. This effect appeared to be stronger in breast cancer cases in premenopausal women (46).

Conclusion

Older men who wish to conceive a child should be better informed of the risks of conditions that can occur in their offspring. Currently, there are no screening or diagnostic test panels that specifically target conditions that increase with paternal age. Couples need to be counseled that, while there is no agreement on the existence or identity of a discrete point at which advanced paternal age begins, the risks of disorders in offspring increase continuously over time. Despite the increased risk, a pregnancy involving a man with advanced paternal age should be treated similar to any other pregnancy, according to the prenatal diagnosis guidelines established by the American College of Medical Genetics (22).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R.R. is a K12 scholar supported by a Male Reproductive Health Research Career Development Physician-Scientist Award (grant no. HD073917-01) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Program to D.J.L.

Footnotes

Discuss: You can discuss this article with its authors and with other ASRM members at http://fertstertforum.com/ramasamyr-risks-advanced-paternal-age/

R.R. has nothing to disclose. K.C. has nothing to disclose. P.B. has nothing to disclose. D.J.L. has nothing to disclose.

R.R. and K.C. should be considered similar in author order.

References

- 1.Carolan M, Frankowska D. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome: a review of the evidence. Midwifery. 2011;27:793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YJ, Lee JE, Kim SH, Shim SS, Cha DH. Maternal age-specific rates of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in Korean pregnant women of advanced maternal age. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:160–6. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2013.56.3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray I, Gunnell D, Davey Smith G. Advanced paternal age: how old is too old? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:851–3. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frattarelli JL, Miller KA, Miller BT, Elkind-Hirsch K, Scott RT., Jr Male age negatively impacts embryo development and reproductive outcome in donor oocyte assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford WC, North K, Taylor H, Farrow A, Hull MG, Golding J. Increasing paternal age is associated with delayed conception in a large population of fertile couples: evidence for declining fecundity in older men. The ALSPAC Study Team (Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood) Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1703–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.8.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:724–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray PB, Singh AB, Woodhouse LJ, Storer TW, Casaburi R, Dzekov J, et al. Dose-dependent effects of testosterone on sexual function, mood, and visuospatial cognition in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3838–46. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellstrom WJ, Overstreet JW, Sikka SC, Denne J, Ahuja S, Hoover AM, et al. Semen and sperm reference ranges for men 45 years of age and older. J Androl. 2006;27:421–8. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neaves WB, Johnson L, Petty CS. Age-related change in numbers of other interstitial cells in testes of adult men: evidence bearing on the fate of Leydig cells lost with increasing age. Biol Reprod. 1985;33:259–69. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod33.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson L, Zane RS, Petty CS, Neaves WB. Quantification of the human Sertoli cell population: its distribution, relation to germ cell numbers, and age-related decline. Biol Reprod. 1984;31:785–95. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod31.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhnert B, Nieschlag E. Reproductive functions of the ageing male. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:327–9. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lansac J. Delayed parenting. Is delayed childbearing a good thing? Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1033–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathieu C, Ecochard R, Bied V, Lornage J, Czyba JC. Cumulative conception rate following intrauterine artificial insemination with husband’s spermatozoa: influence of husband’s age. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1090–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dain L, Auslander R, Dirnfeld M. The effect of paternal age on assisted reproduction outcome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyrobek AJ, Eskenazi B, Young S, Arnheim N, Tiemann-Boege I, Jabs EW, et al. Advancing age has differential effects on DNA damage, chromatin integrity, gene mutations, and aneuploidies in sperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9601–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506468103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spano M, Bonde JP, Hjollund HI, Kolstad HA, Cordelli E, Leter G. Sperm chromatin damage impairs human fertility. The Danish First Pregnancy Planner Study Team. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez G, Lafuente R, Checa MA, Carreras R, Brassesco M. Diagnostic value of sperm DNA fragmentation and sperm high-magnification for predicting outcome of assisted reproduction treatment. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:790–4. doi: 10.1038/aja.2013.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Showell MG, Mackenzie-Proctor R, Brown J, Yazdani A, Stankiewicz MT, Hart RJ. Antioxidants for male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD007411. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007411.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zini A, Azhar R, Baazeem A, Gabriel MS. Effect of microsurgical varicocelectomy on human sperm chromatin and DNA integrity: a prospective trial. Int J Androl. 2011;34:14–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Rochebrochard E, Thonneau P. Paternal age and maternal age are risk factors for miscarriage; results of a multicentre European study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1649–56. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nybo Andersen AM, Hansen KD, Andersen PK, Davey Smith G. Advanced paternal age and risk of fetal death: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:1214–22. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toriello HV, Meck JM, for the Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee Statement on guidance for genetic counseling in advanced paternal age. Genet Med. 2008;10:457–60. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318176fabb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenfield PJ, Kleinhaus K, Opler M, Perrin M, Learned N, Goetz R, et al. Later paternal age and sex differences in schizophrenia symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrey EF, Buka S, Cannon TD, Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Liu T, et al. Paternal age as a risk factor for schizophrenia: how important is it? Schizophr Res. 2009;114:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ, Sloter E, Kidd SA, Moore L, Young S, et al. The association of age and semen quality in healthy men. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:447–54. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiener-Megnazi Z, Auslender R, Dirnfeld M. Advanced paternal age and reproductive outcome. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:69–76. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong A, Frigge ML, Masson G, Besenbacher S, Sulem P, Magnusson G, et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 2012;488:471–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zollner U, Dietl J. Perinatal risks after IVF and ICSI. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:17–22. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penrose LS. Parental age and mutation. Lancet. 1955;269:312–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(55)92305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wynn J, King TM, Gambello MJ, Waller DK, Hecht JT. Mortality in achondroplasia study: a 42-year follow-up. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2502–11. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkie AO, Slaney SF, Oldridge M, Poole MD, Ashworth GJ, Hockley AD, et al. Apert syndrome results from localized mutations of FGFR2 and is allelic with Crouzon syndrome. Nat Genet. 1995;9:165–72. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goriely A, McGrath JJ, Hultman CM, Wilkie AO, Malaspina D. “Selfish spermatogonial selection”: a novel mechanism for the association between advanced paternal age and neurodevelopmental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:599–608. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goriely A, McVean GA, Rojmyr M, Ingemarsson B, Wilkie AO. Evidence for selective advantage of pathogenic FGFR2 mutations in the male germ line. Science. 2003;301:643–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1085710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiemann-Boege I, Navidi W, Grewal R, Cohn D, Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ, et al. The observed human sperm mutation frequency cannot explain the achondroplasia paternal age effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14952–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232568699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin RH. Meiotic chromosome abnormalities in human spermatogenesis. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;22:142–7. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaragoza MV, Jacobs PA, James RS, Rogan P, Sherman S, Hassold T. Nondisjunction of human acrocentric chromosomes: studies of 432 trisomic fetuses and liveborns. Hum Genet. 1994;94:411–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00201603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowe X, Eskenazi B, Nelson DO, Kidd S, Alme A, Wyrobek AJ. Frequency of XY sperm increases with age in fathers of boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1046–54. doi: 10.1086/323763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ, Kidd SA, Lowe X, Moore D, 2nd, Weisiger K, et al. Sperm aneuploidy in fathers of children with paternally and maternally inherited Klinefelter syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:576–83. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanfranco F, Kamischke A, Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E. Klinefelter’s syndrome. Lancet. 2004;364:273–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16678-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werler S, Demond H, Damm OS, Ehmcke J, Middendorff R, Gromoll J, et al. Germ cell loss is associated with fading Lin28a expression in a mouse model for Klinefelter’s syndrome. Reproduction. 2014;147:253–64. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sciurano RB, Luna Hisano CV, Rahn MI, Brugo Olmedo S, Rey Valzacchi G, Coco R, et al. Focal spermatogenesis originates in euploid germ cells in classical Klinefelter patients. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2353–60. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fonseka KG, Griffin DK. Is there a paternal age effect for aneuploidy? Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;133:280–91. doi: 10.1159/000322816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray L, McCarron P, Bailie K, Middleton R, Davey Smith G, Dempsey S, et al. Association of early life factors and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood: historical cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:356–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yip BH, Pawitan Y, Czene K. Parental age and risk of childhood cancers: a population-based cohort study from Sweden. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1495–503. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hemminki K, Kyyronen P. Parental age and risk of sporadic and familial cancer in offspring: implications for germ cell mutagenesis. Epidemiology. 1999;10:747–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi JY, Lee KM, Park SK, Noh DY, Ahn SH, Yoo KY, et al. Association of paternal age at birth and the risk of breast cancer in offspring: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.