Abstract

Although attention bias towards threat has been causally implicated in the development and maintenance of fear and anxiety, the expected associations do not appear consistently. Reliance on a single task to capture attention bias, in this case overwhelmingly the dot-probe task, may contribute to this inconsistency. Comparing across attentional bias measures could help capture patterns of behavior that have implications for anxiety. This study examines the patterns of attentional bias across two related measures in a sample of children at temperamental risk for anxiety. Children (Meanage=10.19±0.96) characterized as behaviorally inhibited (N=50) or non-inhibited (N=64) via parent-report completed the dot-probe and affective Posner tasks to measure attentional bias to threat. Parent-report diagnostic interviews assessed children's social anxiety. Behavioral inhibition was not associated with performance in the dot-probe task, but was associated with increased attentional bias to threat in the affective Posner task. Cross-task convergence was dependent on temperament, such that attention bias across the two tasks was only related in behaviorally inhibited children. Finally, children who were consistently biased across tasks (showing high or low attentional bias scores in both tasks, rather than high in one but low in the other) had higher levels of anxiety. Convergence across attention bias measures may be dependent on individuals' predispositions (e.g., temperament). Moreover, convergence of attention bias across measures may be a stronger marker of information processing patterns that shape socioemotional outcomes than performance in a single task.

A growing literature base suggests that individuals with high trait or clinical anxiety levels show an attention bias (AB) to threat (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007). This bias is evident in children and adults across diagnoses (Bar-Haim et al., 2007), and manipulating the level of bias (through AB Modification) appears to modulate anxiety levels (Hakamata et al., 2010; MacLeod & Clarke, 2015). As a result, many suggest that AB to threat plays a causal role in the emergence of anxiety (Van Bockstaele et al., 2014). Yet, there is a good deal of inconsistency in the literature as some data point to anxiety-linked attention avoidance (Brown et al., 2013; Mansell, Clark, Ehlers, & Chen, 1999; Morales, Pérez-Edgar, & Buss, 2014; Salum et al., 2013; Stirling, Eley, & Clark, 2006; Waters, Bradley, & Mogg, 2014) and other data show null findings when comparing anxious/at-risk participants against healthy controls (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011; Waters, Lipp, & Spence, 2004). These mixed findings may be due to AB being measured overwhelmingly with one task—the dot-probe task. If AB acts as a trait-level mechanism, we would expect a bias to appear at multiple points in the attentional system and exhibit consistency across contexts. The dot-probe task by itself may be insufficiently sensitive to fully capture the biases in attention that influence social anxiety.

Few studies have examined potential convergence among AB measures, which would perhaps better capture the atypical threat load on the attentional system associated with anxiety. It may be that some individuals consistently show a bias to threat, while others display a bias on only a subset of measures. Indeed, individuals may be at highest risk when they exhibit consistent AB across multiple measures, reflecting stable or entrenched processing patterns and removing the “noise” of specific task parameters. The present study evaluates the relations across two AB tasks and their concordant impact on anxiety in a sample of children at temperamental risk for anxiety.

Behavioral Inhibition (BI) is an early emerging temperamental type marked by high fear towards novelty and social reticence (N. A. Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005). Children who exhibit stable BI are at increased risk for anxiety during adolescence, particularly social anxiety (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009), making it one of the best early predictors of anxiety. However, not all children classified as BI display inhibition at later ages and only ~40% go on to develop anxiety problems (Clauss & Blackford, 2012). Intervention efforts need to identify the factors that moderate the stability of BI, as well as the association between early BI and anxiety. One such factor is AB towards threat.

Studies examining AB in BI have been sparse with mixed results. Adolescents characterized as BI in childhood exhibited a larger bias towards threat in adolescence versus non-BI (BN) peers (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010), while no AB difference was found at age 5 between BI and BN children (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011). This young sample also failed to show group differences when AB to threat was measured again at age 7 (White et al., in press). However, in all three studies, AB moderated the relation between BI and anxiety-related outcomes. Specifically, BI children continued to display inhibited behavior in childhood and adolescence only if they also displayed AB towards threat. Similarly, early BI only predicted anxiety later in childhood for children who exhibited a bias towards threat.

The existing evidence suggests that AB towards threat is an important developmental tether impacting broad information processing patterns such that this bias impacts their interpretation of, memory for, and response to the environment, keeping them at risk for anxiety across development (Pérez-Edgar, Taber-Thomas, Auday, & Morales, 2014). However, it is unclear if there are stable group-level differences in AB between BI and BN children. The broader AB to threat literature presents a similar scenario, as several studies do not find group differences between anxious and non-anxious participants (Waters et al., 2004), while other studies find that anxious individuals (Brown et al., 2013; Mansell et al., 1999; Salum et al., 2013; Stirling et al., 2006; Waters et al., 2014), as well as individuals at temperamental risk for anxiety (Morales et al., 2014), display AB away from threat.

The AB literature is heavily based on the dot-probe task (Todd, Cunningham, Anderson, & Thompson, 2012). In this task, individuals briefly see two competing stimuli (one neutral and one threatening) and then respond to a probe that appears in the same location as one of the stimuli. An AB towards emotional stimuli is present when participants preferentially attend to emotional cues, marked by decreased reaction times (RTs) to probes replacing the threatening cues compared to the neutral cues, presuming that faster responses indicate that attention was already at that location. Bias is reflected in a simple difference score comparing RTs across cueing conditions. While its wide adoption greatly aids in cross-study comparisons, it is possible that using a single task is not sufficient to evaluate the impact of AB on anxiety. Attention bias may emerge from different stages of the attentional process. Comparisons across domains and/or employing multiple tasks that capture multiple facets of AB may help better characterize attention and evaluate which patterns of AB across tasks are most predictive of risk. The present study focuses on the latter, relying on two widely used measures as an initial examination.

The few studies that have compared the dot-probe task to other measures of AB have found no relation between tasks (Broeren, Muris, Bouwmeester, Field, & Voerman, 2011; Brown et al., 2014; Dalgleish et al., 2003). However, the tasks were often dissimilar in scope (e.g., the dot-probe task using faces vs. the emotional Stroop task using words; Dalgleish et al., 2003). In addition, it is possible that convergence in AB is observed only in individuals at highest risk for, or with the highest levels of, anxiety. In this way, the convergence of AB across tasks may itself be a meaningful individual difference variable.

Several tasks have been used to measure AB (see Van Bockstaele et al., 2014). The Posner task (or attentional cueing task) is the most similar to the dot-probe task. In the Posner task (Posner, 1980), a single cue briefly appears on one side of the visual field (left or right). Following cue removal, a target probe appears either in the same location as the cue (valid trials) or on the opposite side of the cue (invalid trials). The validity score is the RT on invalid trials minus valid trials. This difference (the validity effect) is believed to represent the effort required to disengage from invalid cues. In the affective Posner task, the cues have an emotional valence based on punishment and reward cues, emotional words, or emotional facial expressions (Derryberry & Reed, 2002; E. Fox, Russo, Bowles, & Dutton, 2001; Pérez-Edgar, Fox, Cohn, & Kovacs, 2006; Van Damme & Crombez, 2009).

Anxious individuals have greater difficulty with attention disengagement (larger validity effects) in the affective Posner task (Cisler & Olatunji, 2010; Derryberry & Reed, 2002; E. Fox, Russo, Bowles, & Dutton, 2001). In the only affective Posner task study with BI, children completed the original task under neutral and affectively charged conditions (Pérez-Edgar & Fox, 2005). BI children exhibited a larger validity effect, larger event-related potentials, and greater right electroencephalogram asymmetry compared to BN children only under the affective condition.

The current study examined the association between AB to threat as measured by the dot-probe and affective Posner tasks in BI and BN children. First, we tested the relation between BI, anxiety, and AB towards threat for each task separately. We hypothesized that BI children would display a larger bias towards threat in both tasks. Second, we tested the relation between the two tasks and then looked to see if the relation varied by BI status. We hypothesized that bias patterns would be related, particularly in BI individuals since they are at increased risk for anxiety. Third, we explored the possibility that convergent patterns of AB across the two tasks were related to anxiety levels. Finally, we examined if the relation between patterns of attention in the tasks and anxiety differs by BI status.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 114 9–12 year olds (55 boys; Meanage=10.19; SD=0.96). Families were recruited through a university database of families interested in participating in research studies, community outreach, and word-of-mouth. As part of a larger study on temperament, attention, and anxiety, the tasks were typically completed on separate testing days (97%, Meangap=6 days). Participants were screened using parental report on the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ; Bishop, Spence, & McDonald, 2003). Children who met BI cutoff scores (>120 in BIQ Total score or >60 in BIQ Social novelty; ~25% of children screened) were identified and oversampled (N=50), while children below cutoff were recruited as a gender- and age-matched non-BI comparison group (N=64; not yoked). Our cut-off scores were based on previous studies of extreme temperament in children (Broeren & Muris, 2010). The sample was 69.3% Caucasian, 1.8% African American, 5.3% biracial, 1.8% other ethnicities, and 21.9% did not answer. Exclusionary criteria included severe psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., bipolar disorder), IQ below 70, or severe medical illness. Parents and children provided written consent/assent and the Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Children were excluded due to being a member of a sibling pair participating in the study (N=3) or poor performance (<75% accuracy) in the dot-probe (N=14) or affective Posner (N=2) tasks. The 93 children with data for cross-task analyses did not differ from the rest of the sample in any of the study measures, t's<1.24, p's>.27, d's<.64.

Measures

Behavioral Inhibition was assessed using the BIQ (Bishop et al., 2003), a 30-item measure assessing the frequency of BI-linked behavior in the domains of social and situational novelty on a seven-point scale from 1 (“hardly ever”) to 7 (“almost always”). The questionnaire has adequate internal consistency and validity in differentiating BI from BN children (Bishop et al., 2003) and parent-reports on the BIQ correlate with laboratory observations of BI (Dyson, Klein, Olino, Dougherty, & Durbin, 2011). The BIQ had good internal consistency in the current study (α=.91).

Social Anxiety Symptoms were assessed via parent report on the computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children version 4 (C-DISC 4; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). A trained research assistant conducted the semi-structured interview, in which parents judged DSM-IV symptoms as either present (“yes”) or absent (“no”). A continuous measure of endorsed symptoms (symptom count) was used in this study.

AB to Threat was measured via the dot-probe and affective Posner tasks. We removed incorrect trials, trials with RTs of less than 150ms or more than 2000ms, and trials with RTs +/− 2 SDs from an individual's mean before analyses.

Dot-probe task

Each trial began with a 500ms fixation, followed by a face pair displayed above and below the fixation point (500ms). The faces were replaced by an arrow-probe presented (1000ms) in the location of one of the faces. Children indicated as quickly and accurately as possible whether the arrow pointed left or right via button press (response recorded for 2500ms). The visual angle for the face stimulus was 5.3°(H)*6.2°(V). Inter-trial intervals varied between 250ms to 750ms (average 500ms).

Face pairs of 10 actors (5 female; NimStim, Tottenham et al., 2009) were displayed across 240 trials divided into two runs with 80 trials per condition: congruent trials, in which the angry-neutral face pair was followed by an arrow in the same position as the angry face; incongruent trials, in which the probe appeared on the opposite side of the angry face; and neutral-neutral trials, with the probe in either location. AB scores to angry faces were calculated as mean RT for incongruent trials minus mean RT for congruent trials. Positive values indicate a bias towards threat whereas negative values indicate bias away from threat.

Affective Posner task

Each trial began with a 500ms fixation, followed by a single face presented on the middle, left, or right of the fixation (500ms). The faces were replaced by a white square (1000ms) in either the left or right face location. Participants indicated as quickly and accurately as possible the location of the square via button press (response recorded for 2500ms). The visual angle for the face stimulus was 3.8°(H)*4.7°(V). The inter-trial interval was 500ms.

The same face pairs were used in both tasks. There were on average 33 trials per condition: angry valid trials, in which the angry face was followed by a square in the same spatial location; angry invalid trials, in which the angry face was replaced by a square on the opposite location; and angry middle trials, in which the angry face appeared on the middle of the screen (fixation probe location) followed by a square on either side (left or right). Neutral valid, invalid, and middle trials were identical, but with a neutral face serving as the cue rather than an angry face. Middle trials served as controls and catch trials. The validity score was calculated as the average RT to targets in invalid trials minus the average RT to targets in valid trials for angry and neutral cues separately. This generated an angry validity score and a neutral validity score; positive values represent the effort to disengage from the cue in invalid trials.

Statistical Analyses

To test for differences in the dot-probe task, an independent samples t-test examined the effect of BI status (BI vs. BN) on AB. One-sample t-tests versus zero were used to separately assess group patterns of AB. For the affective Posner task, a 2×2×2 repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine the effect of trial (valid vs. invalid), emotion (angry vs. neutral), and BI status (BI vs. BN). To test for group differences in the affective Posner task, an independent sample t-test was used to examine the effect of BI status on angry and neutral validity scores.

To test the relation between the two tasks, and for potential variation in this relation by BI status, we employed a hierarchical regression predicting AB in the dot-probe task using BI, AB in the affective Posner task (angry validity score), and their interaction (mean centered). To probe the interaction, we tested the correlation between tasks for each group (BI and BN) separately.

Next, we evaluated the association of AB pattern with anxiety, creating four groups based on median split (Mediandot-probe=−0.37; MedianPosner=5.00): a group with high bias scores in both tasks (N=25), a group with high bias scores in the dot-probe and low angry validity scores in the affective Posner (N=22), a group with low bias scores in the dot-probe and high validity scores in the Posner (N=21), and a group with low scores in both tasks (N=25). To test the three hypotheses related to this aim, we employed a one-way ANOVA with polynomial contrasts to allow non-linear relations. Finally, to explore the association between BI and AB pattern across tasks, we tested the significance of the three-way interaction of BI status, dot-probe bias, and affective Posner bias in predicting anxiety via hierarchical regression.

Results

BI, Anxiety, and AB towards Threat

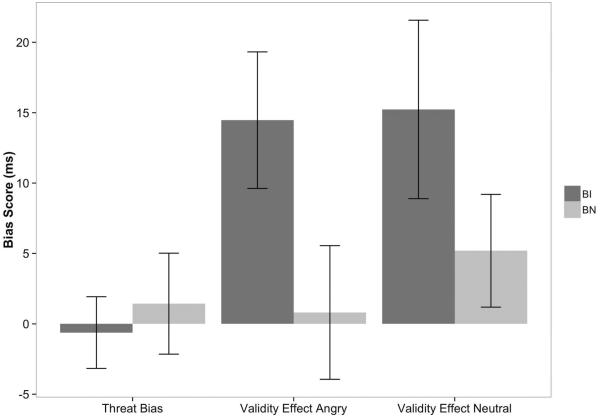

In the dot-probe task, there was no difference between BI and non-BI children in AB towards threat, t(109)=0.59, p=.56, d=0.11. Moreover, neither group displayed a significant bias, t's<0.58, p's>.56, d's<0.15 (Figure 1 & Table 1).

Figure 1.

Differences in AB towards threat in the dot-probe and affective Posner tasks between BI and BN children. Error bars represent standard error.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of main variables by BI status.

| BI | Non-BI | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| % Boys | 48.0% | 48.4% |

| IQ | 108.74 (14.58) | 111.13 (12.27) |

| Threat Bias (ms) | −0.51 (15.98) | 1.20 (16.29) |

| Neutral Validity Effect (ms) | 15.23 (43.45) | 5.19 (31.57) |

| Angry Validity Effect (ms) | 14.47 (33.24) | 0.81 (37.42) |

| Social Phobia | 4.17 (3.87) | 0.61 (1.94) |

Note: Bolded = p<.05.

For the affective Posner task, we noted a significant main effect for validity score, F(1,107)=8.78, p=.004, η2=.08. Participants were slower to respond to incongruent trials (MValid=446.23, SD=66.88; MInvalid=454.20, SD=66.37), t(108)=−2.64, p=.01, d=−0.12, regardless of emotion-cue and BI status. No other main effects or interactions were significant. Given the a priori hypotheses of differences in angry validity scores between BI and BN children (E. Fox et al., 2001), we performed independent sample t-tests (Figure 1 & Table 1). BI children had a significantly greater validity score for angry faces than BN children, t(107)=−1.98, p=.050, d=−0.39. This effect was not significant when evaluating the neutral validity score (p=.17, d=−0.26).

The only significant predictor of social anxiety was BI, r(112)=.52, p<.0001 (Table 1). There were no significant relations between anxiety, gender, and AB on either task.

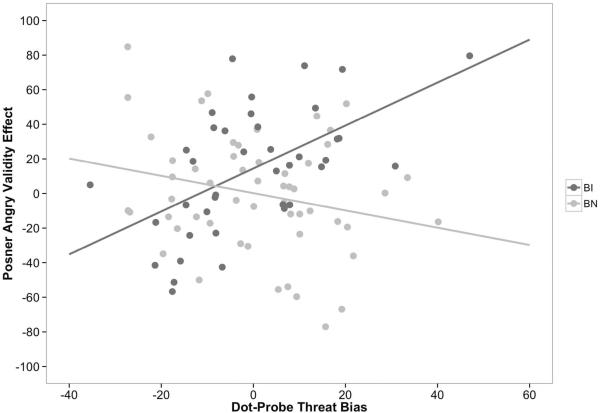

Relations between AB Tasks

Across the entire sample, there were no significant relations between the threat bias score from the dot-probe task and angry or neutral validity scores from the affective Posner task, r's<.20 and p's>.06. However, in the hierarchical regression predicting dot-probe threat bias using BI and angry validity score as predictors, the relation between dot-probe threat bias and Posner angry validity score was dependent on BI status, β=0.52, p=.0002. Performance in the two tasks was positively associated in the BI group, r(37)=.56, p=.0002, but not in the BN group, r(52)=-.24, p=.08 (Figure 2). Moreover, the two relations were significantly different from each other, z=4.02, p=.0001. Neither the overall regression model nor the interaction was significant when evaluating the relation between threat bias and neutral validity score (p's>.31).

Figure 2.

Relation between threat bias score from the dot-probe and angry validity score from the Posner for BI and BN children separately.

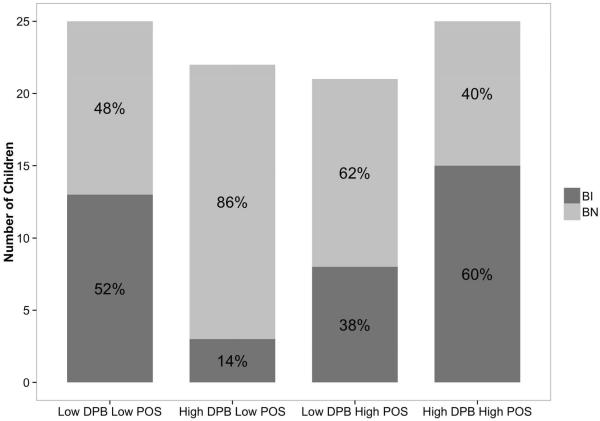

Patterns of AB, BI, and Anxiety

To evaluate the pattern of AB across tasks in relation to anxiety, we created four groups based on median split. BI status was not equally represented among the groups, χ2(3,N=93)=11.75, p=.008. Further probing the chi-square test revealed that there were significantly more BI children in the group with high bias scores in both tasks (Adjusted Standardized Residual=2.1) and significantly fewer BI children in the group with high dot-probe bias scores and low affective Posner bias scores (Adjusted Standardized Residual=-3.1) than expected by chance (Table 2 & Figure 3). This unequal group distribution did not allow us to test the three-way interaction evaluating the association between BI and AB pattern across tasks in predicting level of anxiety.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of main variables by attention bias group.

| Low DPB | Low DPB | High DPB | High DPB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low POS | High POS | Low POS | High POS | |

|

|

||||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| N | 25 | 21 | 22 | 25 |

| % Boys | 44.0% | 52.4% | 54.5% | 48.0% |

| % BI | 52.0% | 38.1% | 13.6% | 60.0% |

| Threat Bias (ms) | −14.65 (8.13) | −10.85 (7.92) | 12.63 (9.07) | 13.53 (11.28) |

| Neutral Validity Effect (ms) | −5.84 (29.65) | 14.52 (30.77) | 3.22 (32.65) | 26.92 (38.59) |

| Angry Validity Effect (ms) | −21.84 (17.41) | 35.24 (21.54) | −21.82 (24.79) | 32.88 (21.09) |

| Social Phobia | 2.52 (3.91) | 1.19 (2.66) | 1.32 (2.84) | 3.08 (3.45) |

Note: DPB=Dot-probe task; POS=Affective Posner task.

Figure 3.

Proportion of BI and BN children by group of cross-task AB patterns. DPB=Dot-probe task; POS=Affective Posner task.

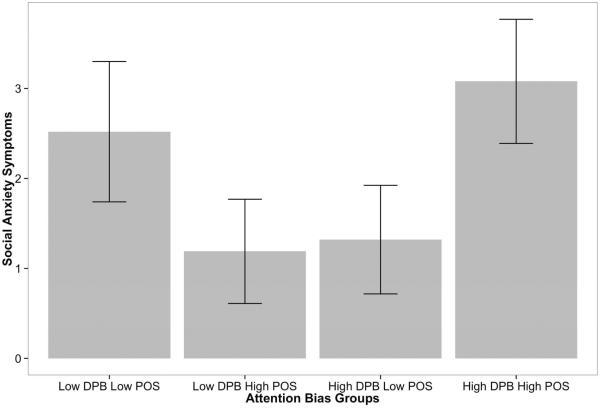

Thus, we examined the interaction between tasks, independent of BI, using a one-way ANOVA with polynomial contrasts (Figure 4). The main effect of bias group on anxiety was not significant, F(3,89)=1.83, p=.15, η2=.06. However, there was a significant quadratic effect, F(1,89)=5.11, p=.026, 95% CI[0.19, 2.91], indicating that anxiety was higher in the two groups with consistent bias (high-high and low-low groups) versus the two groups with inconsistent bias scores (high-low and low-high groups). Neither the ANOVA nor the quadratic contrast was significant, F's<0.86, p's>.36, when controlling for BI, signifying that this finding was dependent on BI status. To test for specificity, bias groups were then created with neutral validity scores rather than angry validity scores; there was no relation with anxiety (quadratic effect; p=.99) or a distinct BI distribution across groups (p=.35).

Figure 4.

Differences in anxiety across of AB pattern groups. Error bars represent standard error. DPB=Dot-probe task; POS=Affective Posner task.

Discussion

The current study examined the relation between AB measured with the dot-probe and affective Posner tasks in children at risk for anxiety. We did not find AB differences between BI and BN children in the dot-probe task. However, BI children showed a larger AB to threat in the affective Posner task compared to BN children. The cross-task correlation of AB was associated with temperamental risk, such that AB was related across tasks only in BI children. Finally, children who were consistently biased across tasks (showing high or low scores in both tasks, rather than high in one but low in the other) had elevated levels of anxiety.

As expected, BI children displayed a significantly larger validity score to angry faces than the BN children during the affective Posner task. Although we cannot presume a specific bias to angry faces (as the ANOVA comparing to neutral trials was not significant and RTs were highly correlated across conditions; see Table S1), this significant difference is in line with previous studies with adults, showing that anxious individuals display larger validity scores to threatening stimuli (E. Fox et al., 2001). In addition, the relations evident with BI and anxiety for angry faces were not significant when probed with neutral faces only. The specific mechanisms underlying the validity effect remain unclear. The common interpretation is that anxious individuals are slower to disengage attention from threatening stimuli. However, this interpretation has been criticized because it assumes that the abrupt onset of a single stimulus draws attention (engagement) equally for anxious and non-anxious individuals, regardless of the emotional valance of the stimulus (Clarke, MacLeod, & Guastella, 2013). Moreover, there may be non-attentional processes that influence RTs, such as behavioral freezing in the presence of threat stimuli by anxious individuals (Mogg, Holmes, Garner, & Bradley, 2008). Even though these issues complicate the interpretation of mechanisms underlying AB in the affective Posner task, our findings indicate differences in information processing between BI and BN that parallel the findings from the adult anxiety literature.

In contrast, there were no differences between BI and BN in the dot-probe task. Although the lack of association between performance on the dot-probe and BI or anxiety ran contrary to some previous studies (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010), the current findings are not surprising given that other studies with BI children have not found this association (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011; White et al., in press). Indeed, the inconsistency of findings with the dot-probe task inspired the currrent study.

AB to threat is likely to have implications for real-world social behavior when it is “consistent”—that is, evident across contexts and attention processes. Previous studies examining convergence between AB measures have found no relation between the dot-probe and other tasks (Broeren et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2014; Dalgleish et al., 2003). This may have been due to the non-similarity between tasks (e.g., dot-probe vs. Emotional Stroop). These null findings likely also reflect the lack of, or failure to account for, a “primed” population of study. Indeed, the current study failed to find a relation between tasks for the whole sample. If threat bias convergence across tasks is itself an important indicator of an individual's threat-related attention processing—the consistency of biases in their attention processing—then we would expect this relation to depend on other factors, such as temperamental risk for anxiety. We find that the relation among tasks was significantly stronger among BI children versus their non-BI peers.

BI children were underrepresented among individuals with inconsistent bias, so it was not possible to evaluate if displaying a bias in both tasks and being BI confered an added risk for anxiety. Nevertheless, the pattern of AB across tasks was related to anxiety level for the sample as a whole. Specifically, children who displayed a consistent bias in both tasks, regardless of direction (bias towards or away from threat), had higher levels of anxiety. While the “high-high” group met our pre-study predictions, the “low-low” group was somewhat unexpected. It is possible that the lack of difficulty disengaging from threat in the Posner task taps an underlying skill that allows for the avoidance pattern evident in the Dot-Probe task. Within the AB literature, some studies find anxiety to be related to a bias towards threat (Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010), while others find a bias away from threat (Brown et al., 2013; Mansell et al., 1999; Morales et al., 2014; Stirling et al., 2006).

Consistent biases toward or away from threat may have distinct implications for adaptive functioning, resulting in heightened or diminished exposure to threat when processing social information, respectively. Future studies should investigate if individuals with stable biases toward or away from threat represent subtypes of risk for anxiety; these opposite extremes of threat bias may differentiate between disorders related to distress (heightened threat bias) and fear (initial vigilance followed by threat avoidance; Salum et al., 2013; Waters et al., 2014).

Future research should also examine AB using eye-tracking measures. Eye-tracking provides more direct measures of attention without relying on RTs, which intermingle cognitive, affective, and motoric processes triggered prior to and after the presentation of the response cue. More nuanced measures of attention may help ellucidate the attentional processes that underlie the observed differences in RT paradigms, allowing us to better understand AB towards and away from threat and their implications for socioemotional development. Moreover, future studies should replicate these findings using diferent stimuli (e.g., different faces, scenes, or words). The present study used the same facial expressions in both tasks, increasing experimental control, but reducing ecological validity. Finally, longitudinal research is needed in order to determine the directionality of the effects described in this study.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate convergence across AB measures in children. The two tasks only showed a relation in BI children. In turn, showing a consistent bias across the two tasks, regardless of bias direction (towards or away), was associated with elevated anxiety. These findings illustrate the importance of examing patterns of attention across tasks, while also considering individuals' socioemotional predispositions. These findings have the potential to aid the early identification of children at risk for anxiety and help develop treatments (e.g., AB modification training) that target more specific and individualized attention processes to shift maladaptive developmental trajectories.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Despite evidence causally implicating attention bias to threat in the development and maintenance of fear and anxiety, the expected associations do not appear consistently.

Reliance on one task as the sole measure of attention bias may contribute to the inconsistency of findings; evaluating cross-task convergence may help identify stable attention patterns.

The present study demonstrates that cross-task convergence of attentional bias to threat is dependent on children's temperament (behavioral inhibition). In addition, children with a consistent bias across tasks had higher levels of anxiety.

Convergence across attention bias measures may be dependent on individuals' predispositions (e.g., temperament) and convergence may serve as a marker of information processing patterns shaping socioemotional outcomes.

References

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(1):1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop G, Spence SH, McDonald C. Can Parents and Teachers Provide a Reliable and Valid Report of Behavioral Inhibition? Child Development. 2003;74(6):1899–1917. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00645.x. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeren S, Muris P. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire in a Non-Clinical Sample of Dutch Children and Adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2010;41(2):214–229. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0162-9. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-009-0162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeren S, Muris P, Bouwmeester S, Field A, Voerman J. Processing Biases for Emotional Faces in 4- to 12-Year-Old Non-Clinical Children: An Exploratory Study of Developmental Patterns and Relationships with Social Anxiety and Behavioral Inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. 2011 http://doi.org/10.5127/jep.016611.

- Brown HM, Eley TC, Broeren S, MacLeod C, Rinck M, Hadwin JA, Lester KJ. Psychometric properties of reaction time based experimental paradigms measuring anxiety-related information-processing biases in children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(1):97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.11.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HM, Mcadams TA, Lester KJ, Goodman R, Clark DM, Eley TC. Attentional threat avoidance and familial risk are independently associated with childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2013;54(6):678–685. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12024. http://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Fox NA. Stable Early Maternal Report of Behavioral Inhibition Predicts Lifetime Social Anxiety Disorder in Adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. http://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Olatunji BO. Components of attentional biases in contamination fear: Evidence for difficulty in disengagement. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(1):74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PJF, MacLeod C, Guastella AJ. Assessing the role of spatial engagement and disengagement of attention in anxiety-linked attentional bias: a critique of current paradigms and suggestions for future research directions. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. 2013;26(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.638054. http://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2011.638054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, Blackford JU. Behavioral Inhibition and Risk for Developing Social Anxiety Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):1066–1075.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T, Taghavi R, Neshat-Doost H, Moradi A, Canterbury R, Yule W. Patterns of Processing Bias for Emotional Information Across Clinical Disorders: A Comparison of Attention, Memory, and Prospective Cognition in Children and Adolescents With Depression, Generalized Anxiety, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(1):10–21. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_02. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(2):225–236. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.225. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson MW, Klein DN, Olino TM, Dougherty LR, Durbin CE. Social and Non-Social Behavioral Inhibition in Preschool-Age Children: Differential Associations with Parent-Reports of Temperament and Anxiety. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2011;42(4):390–405. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0225-6. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox E, Russo R, Bowles R, Dutton K. Do threatening stimuli draw or hold visual attention in subclinical anxiety? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130(4):681–700. http://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.4.681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral Inhibition: Linking Biology and Behavior within a Developmental Framework. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56(1):235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakamata Y, Lissek S, Bar-Haim Y, Britton JC, Fox NA, Leibenluft E, Pine DS. Attention Bias Modification Treatment: A Meta-Analysis Toward the Establishment of Novel Treatment for Anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(11):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Clarke PJF. The Attentional Bias Modification Approach to Anxiety Intervention. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3(1):58–78. http://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614560749. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Clark DM, Ehlers A, Chen Y-P. Social Anxiety and Attention away from Emotional Faces. Cognition & Emotion. 1999;13(6):673–690. http://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379032. [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Holmes A, Garner M, Bradley BP. Effects of threat cues on attentional shifting, disengagement and response slowing in anxious individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(5):656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.011. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Pérez-Edgar KE, Buss KA. Attention Biases Towards and Away from Threat Mark the Relation between Early Dysregulated Fear and the Later Emergence of Social Withdrawal. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9963-9. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9963-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion. 2010;10(3):349–357. doi: 10.1037/a0018486. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0018486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Fox NA. A Behavioral and Electrophysiological Study of Children's Selective Attention Under Neutral and Affective Conditions. Journal of Cognition & Development. 2005;6(1):89–118. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327647jcd0601_6. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Fox NA, Cohn JF, Kovacs M. Behavioral and Electrophysiological Markers of Selective Attention in Children of Parents with a History of Depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(10):1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.036. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Reeb-Sutherland BC, McDermott JM, White LK, Henderson HA, Degnan KA, Fox NA. Attention Biases to Threat Link Behavioral Inhibition to Social Withdrawal over Time in Very Young Children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(6):885–895. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9495-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9495-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Taber-Thomas B, Auday E, Morales S. Temperament and Attention as Core Mechanisms in the Early Emergence of Anxiety. In: Lagattuta KH, editor. Contributions to Human Development. Vol. 26. S. KARGER AG; Basel: 2014. pp. 42–56. Retrieved from http://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/354350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1980;32(1):3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. http://doi.org/10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salum GA, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Gadelha A, Pan P, Tamanaha AC, Pine DS. Threat bias in attention orienting: evidence of specificity in a large community-based study. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43(4):733–45. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001651. http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. http://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling LJ, Eley TC, Clark DM. Preliminary Evidence for an Association Between Social Anxiety Symptoms and Avoidance of Negative Faces in School-Age Children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(3):431–439. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_9. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd RM, Cunningham WA, Anderson AK, Thompson E. Affect-biased attention as emotion regulation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16(7):365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka JW, Leon AC, McCarry T, Nurse M, Hare TA, Nelson C. The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research. 2009;168(3):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele B, Verschuere B, Tibboel H, De Houwer J, Crombez G, Koster EHW. A review of current evidence for the causal impact of attentional bias on fear and anxiety. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(3):682–721. doi: 10.1037/a0034834. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0034834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme S, Crombez G. Measuring attentional bias to threat in children and adolescents: A matter of speed? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2009;40(2):344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.01.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Bradley BP, Mogg K. Biased attention to threat in paediatric anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, separation anxiety disorder) as a function of “distress” versus “fear” diagnostic categorization. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(3):607–616. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000779. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Lipp OV, Spence SH. Attentional bias toward fear-related stimuli: An investigation with nonselected children and adults and children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2004;89(4):320–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.06.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, Henderson HA, Pérez-Edgar KE, Walker OL, Degnan KA, Shechner T, Fox NA. Developmental relations between behavioral inhibition, anxiety, and attention biases to threat and positive information. Manuscript submitted for publication. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12696. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.