Abstract

Background

Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) in men who have sex with men (MSM) is risk-based. Despite high frequencies of oral and receptive anal intercourse (RAI) among women, extragenital screening is not recommended.

Methods

Women (n=175) and MSM (n=224) primarily recruited from a sexually transmitted infections clinic reporting a lifetime history of RAI completed a structured questionnaire and clinician collected swab samples from the rectum, pharynx, vagina (women) and urine (men). CT and GC were detected using two commercial nucleic acid amplified tests (Aptima Combo 2, Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA; Xpert CT/NG, Cepheid Innovation, Sunnyvale, CA).

Results

The median age of the population was 26 years, 62% were Caucasian, and 88% were enrolled from a Sexually Transmitted Diseases clinic. Men were more likely than women to have GC (22.8% vs. 3.4%) and CT (21.9% vs. 12.6%). In men vs. women, GC was detected in 16.5% vs. 2.3% of pharyngeal swabs, 11.6% vs. 2.3% of rectal swabs and 5.4% vs. 2.9% of urine samples or vaginal swabs. CT was detected in 2.2% vs. 1.7% of pharyngeal swabs, 17.4% vs. 11.4% of rectal swabs, and 4.5% vs 10.3% for urogenital sites in men vs. women. Overall 79.6% of CT and 76.5% of GC in men and 18.2% of CT and 16.7% of GC in women were detected only in the pharynx or rectum.

Conclusion

Reliance on urogenital screening alone misses the majority of GC and CT in men and more than 15% of infections in women reporting RAI.

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) are the two most common bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States. In women, screening efforts have focused primarily on genitourinary screening.1 Despite the high frequency of receptive anal intercourse (RAI) among young heterosexual adults2–7 there are no recommendations for routine extragenital screening.1 In men who have sex with men (MSM) the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends annual gonorrhea and chlamydia screening based on risk. Despite numerous publications outlining the rising prevalence of rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia, extragenital screening for these STIs is not always performed when indicated.8

Extragenital CT and GC may be important reservoirs for ongoing disease transmission. High rates of extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia among MSM have been well documented.9–14 Previous studies have reported that among MSM 65 to 70% of extragenital gonorrheal and 75 to 85% of extragenital chlamydial infections were documented in men having no urethral infections.12,15 Thus, there is recent rediscovery that urogenital testing alone misses a large proportion of men who are positive for STIs.16 Urogenital screening in women is reported to miss a smaller percentage of total infections compared to MSM, but the numbers of missed infections in women have been reported to range from 25–30% for GC16,17 and 14–44% for CT.16–19

The objective of this prospective study was to determine the prevalence of CT and GC in men and women using the same inclusion criteria, namely reporting a lifetime history of RAI.

Materials and Methods

Study population and Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2014 to March 2015 at two centers in Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Allegheny County Health Department (ACHD, an STI clinic) and Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC (an outpatient women’s health clinic). Inclusion criteria included a reported lifetime history of RAI. Participants were excluded if they reported use of oral antibiotics over the previous 7 days, use of rectal douche or other rectal products in the past twenty-four hours, and, if female, use of vaginal douche or vaginal product in the previous 24 hours, in order to prevent dilution of sample. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, Pittsburgh, PA. After written informed consent was obtained, a questionnaire was administered to determine age, ethnicity, sexual activity history, pharyngeal and rectal symptoms, and vaginal symptoms in women or urinary symptoms in men.

Specimen Collection

The two swabs collected use NAAT technology: GenProbe’s Aptima Unisex Collection Swab (Aptima, Aptima Combo 2; Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA) and the Cepheid Xpert CT/NG Assay (Xpert, Cepheid Innovation, Sunnyvale, CA). Study clinicians inserted two sequential NAAT swabs approximately 2.5cm above the anal verge and placed each swab into the appropriate transport media. Pharyngeal swabs were collected from each lateral posterior wall, including tonsillar crypts. For males, urine samples were obtained as first-pass collection at least 1 hour or later after last void. For women, vaginal swabs were obtained by clinicians by placing the swab approximately 10cm past the introitus and rotating the swab, without placement of a speculum. The order of collection of the two NAAT swabs was predetermined by computer randomization. An additional swab was obtained from the pharynx for GC culture, which was obtained first per CDC guidelines.1 Culture for GC was not initially included in the study because previous studies found a very low level of sensitivity for culture from rectal swab samples.20,21 However, after an interim analysis of the first 150 participants enrolled and the high number of pharyngeal samples positive for GC, culture testing of the remaining 249 pharyngeal samples was added.

Laboratory Testing for CT and GC

Testing was conducted per package insert (Aptima Combo 2 package insert IN0037-04 Rev A; GeneXpert package insert CXCT/NG-CE-10). Xpert is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared for the detection of CT and GC from genitourinary samples. Neither NAAT method has been FDA cleared for detection of these pathogens from rectal or pharyngeal samples, but Aptima had been previously validated in the reference laboratory (Magee-Womens Research Institute, Pittsburgh, PA) for testing of CT and GC from rectal samples.

The Dacron swab from the pharynx was used to inoculate two selective agar plates (Modified Thayer-Martin agar and GC-Lect agar), and chocolate agar. The plates were transported in a candle jar and in the lab were transferred to a 37°C, 6% CO2 incubator. After 24–48 hours agar plates were examined and gram-negative diplococci having indophenol oxidase enzyme were confirmed using API NH (bioMerieux, Inc, Marcy-I’Etoile, France).

Definition of a Positive Test Result

As both Aptima and Xpert are FDA cleared for genitourinary samples, any positive result from the urine or vagina was defined as positive for infection. For rectal and pharyngeal GC and CT swab samples, any Aptima or Xpert positive result (including a discrepant test result) was verified using the appropriate Aptima CT or Aptima GC assay, which targets different nucleic acid sequences. A pharyngeal culture identifying GC was also defined as a true positive although there were no instances in which culture was positive and NAAT was negative for GC.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics including median, range and frequency distributions were performed for all demographic and risk behavior characteristics. P values were calculated using Fisher’s exact or Mann-Whitney U tests. Data analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software, release 22.0. (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Venn diagrams were created using eulerAPE, version 1.0 (University of Kent, Canterbury, UK).

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

A total of 399 participants were recruited: 224 men and 175 women. The median age of the men and women was similar (26 vs. 27 years), but men had a higher median number of male partners in the previous month (Table 1). Condom use with RAI was reported significantly more for men than women (86.6% vs. 37.7%, p <0.001). RAI after vaginal sex using the same condom in 6 of the last 10 sexual encounters was reported in half of women. Evaluation of swab collection order showed that there was no significant difference in test positivity by order of collection (data not shown).

Table 1.

Study Population

| Men Number (%) n = 224 |

Women Number (%) n = 175 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment Site | <0.001 | ||

| ACHD STD Clinic | 216 (96.4%) | 137 (78.3%) | |

| MWH or other | 8 (3.6%) | 38 (21.7%) | |

| Age, years (median, range) | 26 (18, 62) | 27 (18, 49) | 0.24 |

| Hispanic, Latino | 13 (5.8%) | 9 (5.1%) | 0.83 |

| Predominant Race | 0.001 | ||

| Caucasian | 158 (70.5%) | 91 (52.0%) | |

| Black | 49 (21.9%) | 65 (37.1%) | |

| Other | 17 (7.6%) | 19 (10.9%) | |

| Lifetime History of Sexual Activity | 0.30 | ||

| Men only | 171 (76.3%) | 125 (71.4%) | |

| Both men and women | 53 (23.7%) | 50 (28.6%) | |

| Number of male partners (median, range) | |||

| Past 30 Days | 1.5 (0, 15) | 1 (0, 5) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 Months | 5 (0, 100) | 2 (0, 30) | <0.001 |

| Number of female partners (median, range) | |||

| Past 30 Days | 0 (0, 4) | 0 (0, 2) | 0.96 |

| Past 12 Months | 0 (0, 50) | 0 (0, 4) | 0.57 |

| Sexual Activity | |||

| Receptive Oral Sex | 222 (99.1%) | 172 (98.3%) | 0.66 |

| Insertive Oral Sex | 220 (98.2%) | 170 (97.1%) | 0.51 |

| History of Condom Use During Anal Sex | 194 (86.6%) | 66 (37.7%) | <0.001 |

| Condom Use with last contact | 106 (47.3%) | 35 (20.0%) | <0.001 |

| Traded Sex for money, drugs, food, etc. | 8 (3.6%) | 13 (7.4%) | 0.11 |

| Females Only: | |||

| Last vaginal intercourse with man, days median, range) | 7 (0, 998) | ||

| Anal Sex after vaginal sex without condom change | |||

| N/A | 29 (22.3%) | ||

| Rarely (0–2/10) | 24 (13.7%) | ||

| Occasionally (3–5/10) | 18 (10.3%) | ||

| Most of the time (6–9/10) | 22 (12.6%) | ||

| Always (10/10) | 72 (41.1%) |

ACHD: Allegheny County Health Department, STD: Sexually Transmitted Disease, MWH: Magee-Womens Hospital

Symptoms Associated with Infection

Males with GC were more likely to be symptomatic at any anatomic site (p = 0.02) or have urogenital symptoms (p = 0.001) when compared to men without sexually transmitted infections (Table 2). Men with CT were not more likely to have symptoms at any site than those who tested negative for STIs. Men with GC or CT identified in either rectal or pharyngeal samples were not more likely to be symptomatic than those with no infection. In contrast, women who had pharyngeal GC and CT were more likely to have pharyngeal symptoms than uninfected women (p = 0.003 and 0.02, respectively). Genital infection was not related to urogenital symptoms in women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Symptoms experienced by site of infection

| Men | No infection number (%) n=144 |

Positive GC number (%) n = 51, (%) |

p-value GC | Positive CT number (%) n = 49 |

p-value CT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Site | 41 (28.5) | 24 (47.1) | 0.02 | 21 (42.9) | 0.08 |

| Rectal | 17 (11.8) | 10 (19.6) | 0.17 | 10 (20.4) | 0.15 |

| Pharynx | 21 (14.6) | 8 (15.7) | 0.82 | 7 (14.3) | >0.99 |

| Urinary | 10 (6.9) | 12 (23.5) | 0.001 | 9 (18.4) | 0.08 |

| Women | No infection n=149, (%) |

Positive n = 6, (%) |

Positive n = 22, (%) |

||

| Any Site | 66 (44.3) | 5 (83.3) | 0.09 | 12 (54.5) | 0.49 |

| Rectal | 10 (6.7) | 0 | >0.99 | 0 | 0.36 |

| Pharynx | 17 (11.4) | 4 (66.7) | 0.003 | 7 (31.8) | 0.02 |

| Vaginal | 58 (38.9) | 4 (66.7) | 0.22 | 8 (36.4) | >0.99 |

CT: Chlamydia trachomatis, GC: Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Infections by Site

GC was more common in men vs. women (22.8% vs. 3.4%), and more men tested positive for GC from rectal swabs than women, 11.6% to 2.3% respectively (Table 3). Similarly, a greater proportion of men tested positive for GC from pharyngeal swabs than women, at 16.5% vs. 2.3%, respectively. Overall, 21.9% of men vs. 12.6% of women had CT at any site (Table 3). More women tested positive for genitourinary chlamydia than men at 10.3% compared to 4.5%. Of the 249 pharyngeal swab samples evaluated by culture for GC, only 13 (5.2%) were positive, all of which were also positive by both NAATs.

Table 3.

Prevalence of GC and CT by site

| GC Number Positive (%) | CT Number Positive (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomic Site | Men (n=224) | Women (n=175) | p-value GC | Men (n=224) | Women (n=175) | p-value CT |

| Any Site | 51 (22.8) | 6 (3.4) | <0.001 | 49 (21.9) | 22 (12.6) | 0.02 |

| Rectal | 26 (11.6) | 4 (2.3) | <0.001 | 39 (17.4) | 20 (11.4) | 0.12 |

| Pharynx | 37 (16.5) | 4 (2.3) | <0.001 | 5 (2.2) | 3 (1.7) | >0.99 |

| Urogenital | 12 (5.4) | 5 (2.9) | 0.32 | 10 (4.5) | 18 (10.3) | 0.03 |

CT: Chlamydia trachomatis, GC: Neisseria gonorrhoeae

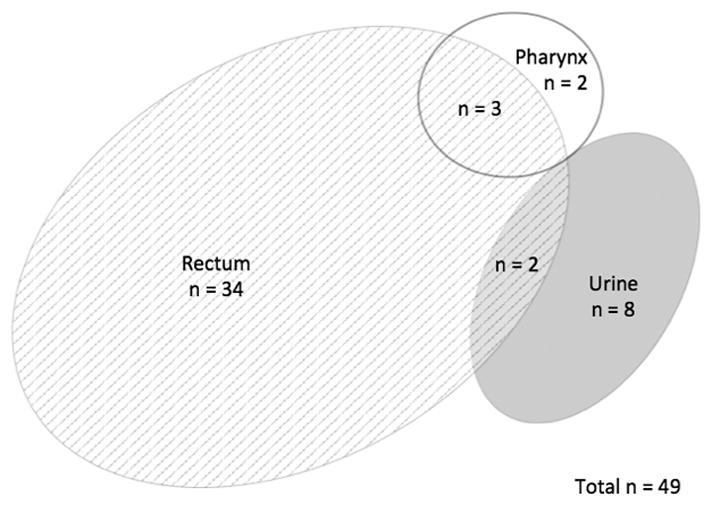

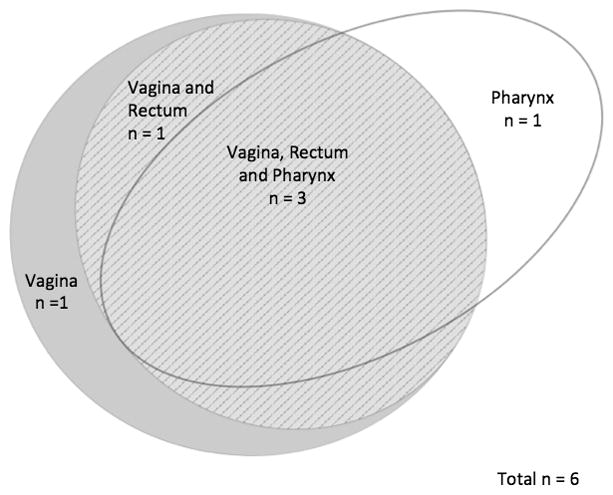

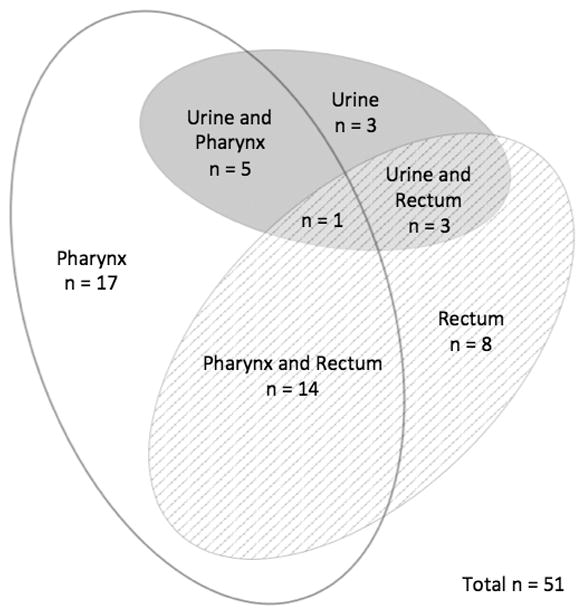

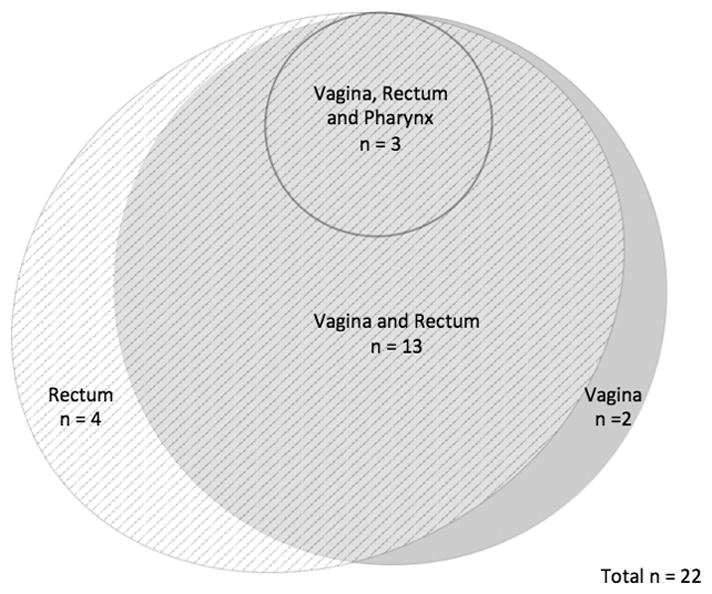

Venn diagrams were created in order to visually display the patterns of STIs by site in order to demonstrate how many cases of extragenital gonorrhea or chlamydia would be missed if only genitourinary screening occurred (Figures 1 through 4). In MSM, 39 of 49 (80%) who tested positive for CT and 39 of 51 (77%) who tested positive for GC were only positive in extragenital sites. Among the 22 women who tested positive for CT at any site, 82% were positive using the vaginal swab sample. Of the 6 women who tested positive for GC at any site, 5 (83%) were positive from the vaginal swab sample. The remaining 1 woman was positive for GC on pharyngeal swab by both NAATs.

Figure 1.

Distribution of C. trachomatis by testing site in men

Figure 4.

Distribution of N. gonorrhoeae by testing site in women

Discussion

This study adds to the growing body of evidence reporting a high prevalence of extragenital STIs among men and women who have a lifetime history of RAI. In MSM the overall prevalence of infection at any site was 22.8% for GC and 21.9% for CT. In women the prevalence of infection at any site was 3.4% for GC and 12.6% for CT. Notably, if genitourinary screening alone was relied upon for men, 80% of chlamydia and 77% of gonorrhea would be missed, a finding which is consistent with other reports.9–16 The results of this study support the current CDC guidelines, which recommend site-specific risk based screening in MSM. A limitation of the present study is that the frequency of receptive anal and oral intercourse was not obtained, and we are thus unable to determine if intercourse frequency predicts GC and CT prevalence.

The population studied resembled the population demographics of other similar studies with respect to age, race, STI history and sexual practices.4,5 In MSM, the prevalence of 11.6% for GC and 17.4% for CT in rectal swab samples was higher than those published from an earlier study with similar inclusion criteria, where rates were 6.2 and 8.9%, respectively.20 The current study also found a higher prevalence of infection compared to various studies of MSM, where the prevalence of rectal CT ranged from 8 to 14%, and rectal GC from 6 to 10%.9–15 Our study showed that pharyngeal infection in MSM was 16.5% for GC and 2.2% for CT, higher than previously reported by a CDC coordinated study in 2007.21 It is unclear whether the high rates of infections observed in the present and other recent studies are attributable to increased rates of infections, a higher level of ascertainment due to the use of multiple tests, or both.

Our results along with published studies suggest that if vaginal screening alone is used, missed infection ranges from 18–40% for GC5,16,17,22 and 6–25% for CT.4,5,16,17,19 Although there was past debate about whether the rectum was truly infected in women having STIs,23 recent reports document that the rectum can serve as a reservoir.24,25 Gratix, et al.18 reported that when CT testing was expanded to include evaluation of rectal swabs, case detection for CT increased by 44%, leading them to support universal screening of women attending STI clinics.

Oral sex is common in men and women, and urogenital organisms are increasingly transmitted to the pharynx. Peters et al. demonstrated that of women who tested positive for CT or GC at any site, one third were positive in the pharynx only.17 In our study, women with pharyngeal GC or CT were more likely to report pharyngeal symptoms in comparison to those without STIs. Although there have been reports of pharyngeal infection resolving spontaneously,26 those with infection can be symptomatic and infections can be transmitted to men by fellatio,27 albeit probably with low efficiency,28 suggesting that the presence CT or GC reflects an important reservoir of infection. Further research addressing gaps in understanding of the role of pharyngeal CT infection and transmission of STIs deserve further study.

Neither NAAT used to identify CT nor GC by pharyngeal swab has been FDA cleared for use in pharyngeal samples. There is concern that NAAT techniques can be false positive for GC due to cross-reaction with the nucleic acid sequences of related organisms, such as N. meningitidis.29 In the present study, all gonococcal infections of the pharynx were confirmed by culture and/or two or more NAATs targeting different sets of primers, suggesting that the high rate of pharyngeal infection was not due to false positive cross-reactivity.

Although there has been a longstanding recognition of the importance of extragenital infections among people having STIs,13,14 this study provides additional data from both men and women who report a lifetime history of RAI. In our study population, screening MSM using only urogenital specimens missed most extragenital infections, while urogenital screening in women missed greater than 17% of bacterial STIs. Careful history taking will help to identify both men and women at risk of extragenital infection, and site-appropriate testing using NAAT techniques should be considered.

Figure 2.

Distribution of N. gonorrhoeae by testing site in men

Figure 3.

Distribution of C. trachomatis by testing site in women

References

- 1.CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gindi RM, Ghanem KG, Erbelding EJ. Increases in oral and anal sexual exposure among youth adolescents attending sexually transmitted diseases clinics in Baltimore, Maryland. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:307–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian LH, Peterman TA, Tao G, et al. Heterosexual anal sex activity in the year after a STD clinic visit. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:905–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318181294b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunte T, Alcaide M, Castro J. Rectal infections with chlamydia and gonorrhoea in women attending a multiethnic sexually transmitted diseases urban clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:819–22. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.009279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Javanbakht M, Guerry S, Gorbach PM, et al. Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal intercourse among clients attending public sexually transmitted disease clinics in Los Angeles County. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra A, Mosher WD, Copen C, et al. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: data from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011;36:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14–94. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papp JR, Schachter J, Gaydos CA, et al. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae - 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63:1–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annan NT, Sullivan AK, Nori A, et al. Rectal chlamydia – a reservoir of undiagnosed infection in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infection. 2009;85:176–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, et al. Prevalence of rectal, urethral and pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:67–74. doi: 10.1086/430704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbee LA, Dombrowski JC, Kerani R, et al. Effect of nucleic acid amplification testing on detection of extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydial infections in men who have sex with men sexually transmitted disease clinic patients. 2014;41:168–72. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gratrix J, Singh AE, Bergman J, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea cases among men who have sex with men after the introduction of nucleic acid amplification test screening at 2 Canadian sexually transmitted infection clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:589–91. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janda WM, Bonhoff M, Morello JA, et al. Prevalence and site-pathogen studies of Neisseria meningitides and N gonorrhoeae in homosexual men. JAMA. 1980;244:2060–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handsfield HH, Knapp JS, Diehr PK, et al. Correlation of auxotype and penicillin susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with sexual preference and clinical manifestations of gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patton ME, Kidd S, Llata E, et al. Extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia testing and infection among men who have sex with men – STD surveillance network, United States 2010 – 2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1564–70. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trebach JD, Chaulk CP, Page KR, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis among women reporting extragenital exposures. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:233–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters RP, Nijsten N, Mutsaers J, et al. Screening of oropharynx and anorectum increases prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in female STD clinic visitors. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:783–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31821890e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gratrix J, Singh AE, Bergman J, et al. Evidence of increased chlamydia case finding after the introduction of rectal screening among women attending 2 Canadian sexually transmitted infection clinics. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:398–404. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladd J, Hsieh YH, Barnes M, et al. Female users of internet-based screening for rectal STIs: descriptive statistics and correlates of positivity. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:485–90. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cosentino LA, Campbell T, Jett A, et al. Use of nucleic acid amplification testing for diagnosis of anorectal sexually transmitted infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2005–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00185-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC. Clinic-based testing for rectal and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections by community-based organizations - five cities, United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:716–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giannini CM, Kim HK, Mortensen J, et al. Culture of non-genital sites increases the detection of gonorrhea in women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinghorn GR, Rashid S. Prevalence of rectal and pharyngeal infection in women with gonorrhoea in Sheffield. Br J Vener Dis. 1979;55:408–10. doi: 10.1136/sti.55.6.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rank RG, Yeruva L. Hidden in plain sight: Chlamydial gastrointestinal infection and its relevance to persistence in human infection. Infect Immun. 2014;82(4):1362–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01244-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craig AP, Kong FYS, Yeruva L, et al. Is it time to switch to doxycycline from azithromycin for treating genital chlamydial infections in women? Modelling the impact of autoinoculation from the gastrointestinal tract to the genital tract. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:200. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0939-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutt DM, Judson FN. Epidemiology and treatment of oropharyngeal gonorrhea. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:655–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-5-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein KT, Stephens SC, Barry PM, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae transmission from the oropharynx to the urethra among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1793–7. doi: 10.1086/648427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lafferty WE, Hughes JP, Handsfield HH. Sexually transmitted diseases in men who have sex with men. Acquisition of gonorrhea and nongonococcal urethritis by fellatio and implications of STD/HIV prevention. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:272–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagasawa Z, Ikeda-Dantsuji Y, Niwa T, et al. Evaluation of APTIMA Combo 2 for cross-reactivity with oropharyngeal Neisseria species and other microorganisms. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:776–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]