Abstract

Context

Language barriers can influence the health quality and outcomes of Limited English Poficiency (LEP) patients at end of life, including symptom assessment and utilization of hospice services.

Objective

To determine how professional medical interpreters influence the delivery of palliative care services to LEP patients.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature in all available languages of six databases from 1966 to 2014. Studies evaluated use of language services for LEP patients who received palliative care services. Data were abstracted from ten articles and collected on study design, size, comparison groups, outcomes and interpreter characteristics.

Results

Six qualitative and four quantitative studies assessed the use of interpreters in palliative care. All studies found that the quality of care provided to LEP patients receiving palliative services is influenced by the type of interpreter used. When professional interpreters were not used, LEP patients and families had inadequate understanding about diagnosis and prognosis during goals of care conversations, and patients had worse symptom management at the end of life, including pain and anxiety. Half of the studies concluded that professional interpreters were not utilized adequately and several suggested that pre-meetings between clinicians and interpreters were important to discuss topics and terminology to be used during goals of care discussions.

Conclusion

LEP patients had worse quality of end-of-life care and goals of care discussions when professional interpreters were not used. More intervention studies are needed to improve the quality of care provided to LEP patients and families receiving palliative services.

Keywords: cancer, end of life, interpreter use, non-English speaking patients, hospice, palliative care, limited English proficiency

Introduction

The demographics of the United States have been changing throughout the years, with more than 60.6 million Americans (21%) over the age of five now speaking a language other than English at home.1 Of these individuals, approximately 25 million (41.8%) report speaking English less than “very well” or having limited English proficiency (LEP).

Language barriers contribute to worse health care quality and outcomes for LEP patients. It is well established that language barriers impede patient-provider communication.2–4 LEP patients have lower satisfaction with care, lower rates of mental health visits, and more problems with communication in the acute care setting.5–7 LEP patients are vulnerable to inadequate assessment of and poorly-controlled pain.6,8 Cultural and linguistic differences may influence how physicians assess pain in LEP patients9 and how LEP patients report pain.10 Language barriers also can lead to misunderstandings between physicians and patients and unnecessary physical emotional and spiritual suffering, particularly at the end of life.11

Effective communication, including delivering appropriate information and understanding the patient and his/her family, is critical to providing adequate palliative care and pain management.12 Among Latinos, language barriers lead to lower utilization of hospice services and inadequate bereavement services for family members of LEP patients because of a lack of both hospice literature in Spanish and Spanish-speaking health care providers.13–16 As physical symptoms rapidly change at the end of life, palliative care services are imperative even in the face of cultural and linguistic differences.13, 17

Professional medical interpreters reduce errors in message delivery and improve patient understanding and comprehension.4, 18–21 The Office of Minority Health (OMH) developed the National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards in Health and Health Care to improve the quality of care for LEP patients, which include a standard for timely access to language assistance for LEP individuals.22 The type of interpreter provided to LEP patients can influence the quality of care delivered.4 Professional interpreters have specific credentials and training to assure their competence.23 A study of Spanish-speaking patients showed that using professional interpreters leads to increased patient satisfaction compared to untrained ad hoc interpreters.24 Professional interpreters have been shown to improve clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction compared to ad hoc interpreters.4, 20, 21 Despite this, many health care facilities attempt to bridge language barriers by using ad hoc interpreters, such as family members of patients or bilingual staff who have not had their language skills assessed.25

No previous reviews have assessed the impact of interpreters on the quality of care and outcomes at the end of life for LEP patients. We conducted a systematic review to understand the influence that interpreters have on communication across language barriers in palliative care, including goals of care discussions, family meetings, end-of-life care, and symptom management. The aim of the review was to narratively summarize the current literature, assess the quality of studies, identify gaps in the literature and provide recommendations for further research to reduce disparities in the care provided to LEP patients at the end of life.

Methods

Data Sources

We conducted a literature search of six databases: PubMed (1966 to January 2013), PsycINFO (Psychological Abstracts) via OVID (1966 to January 2013), Web of Science (1966 to January 2013), Cochrane (1966 to January 2013), Embase (1966 to January 2013), and Scopus (1960 to January 2013). The original literature search strategy had three main components: 1) cancer and end-of-life care; 2) medical interpretation; and 3) immigrant/minority status, which were linked together with “AND”. For PubMed, the controlled vocabulary Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) was used. We searched for articles in all available languages. The search provided 6352 articles after removing duplicates.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria was applied to each article: 1) the study population included LEP patients in need of or receiving palliative and/or end-of-life care from any provider or setting; 2) interpreter services were utilized by these patients; 3) there was either (a) a comparison of the interpreter intervention to a control group or another intervention or (b) a qualitative analysis of interpreter use in palliative care; and 4) there was an assessment of the outcomes of the interpreter intervention. Palliative care outcomes included goals of care discussions, completion of advance directives, symptom management, and prognostication discussions. Articles were eliminated without further review if they did not focus specifically on medical interpreting and the receipt of palliative care services such as symptom management, goals of care or end-of-life care (n=6246).

Study Selection

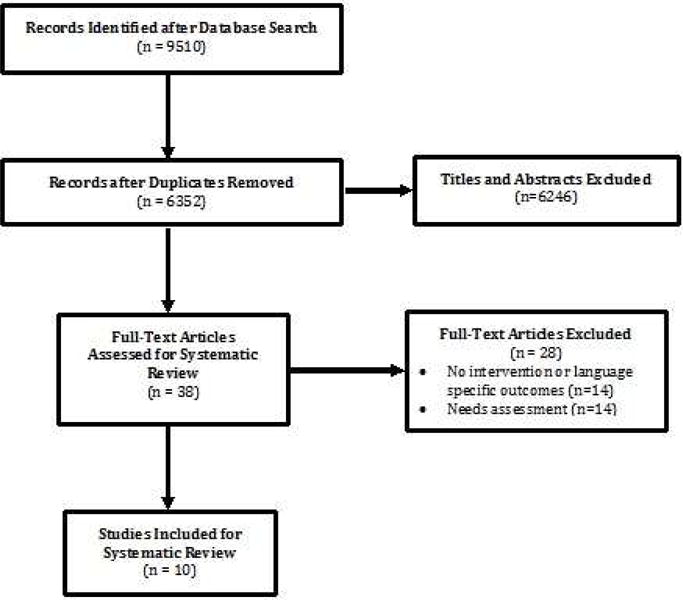

For the purpose of this review, a person acting as an interpreter was defined as any person attempting to bridge language barriers for LEP patients. These included bilingual staff, professional interpreters, health educators and family members. A systematic title and abstract review was conducted by two authors (M.G. and A.Z.) using the PICO framework.26 Articles were included for full review if it was unclear from the abstract that they contained data on the outcomes of language-concordant palliative care. This resulted in 38 articles for full review by four authors (M.S., M.G., A.Z., L.D.). During full review, an additional 27 articles were eliminated that did not focus on the impact of an interpreter on palliative care outcomes (Fig. 1). A total of 10 articles were abstracted and appraised. The variability in study design and wide range of interventions and outcomes examined made pooling of results, quantitative meta-analysis, and calculation of statistical correlations infeasible.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Diagram of Search and Selection Criteria

Data Abstraction

At least two authors abstracted data from the remaining 10 articles. Each article had 14 items extracted: study location, sample size, diagnosis, participants’ ages (including range, mean, and standard deviation), participant race and/or ethnicity, languages interpreted, study design, recruitment methods, type of interpreter, type of palliative service, study site, comparison groups, outcomes and results/major findings. One author (M.S.) reviewed all abstractions and registered any discrepancies between authors. These discrepancies were resolved by consensus among the reviewers.

Quality Appraisal

There is great variability in the methodological quality of the literature regarding medical interpreting.3, 4, 20 In order to allow the reader to assess the quality of each study, all articles were systematically appraised. Randomized and nonrandomized quantitative studies were evaluated with the Downs and Black checklist. The Downs and Black checklist is a scoring algorithm that evaluates articles on reporting of external validity, bias, confounding, and power.27 We used the modified Downs and Black,28 which has a maximum score of 28. To contextualize the Downs and Black score, a previously published qualitative categorization was used to group articles according to their score: ≥20 very good; 15–19 good; 11–14 fair; ≤10 poor.29, 30 For qualitative studies, an 18-question appraisal, created by the United Kingdom’s Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office, was used.31 This framework evaluated articles on their contribution to the literature, defense of the study design used, rigor in the studies’ conduct, and credibility of the findings. To complement the critical appraisal tools, we also abstracted data about the amount of training the interpreters received and whether the language skills of interpreters were assessed.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

The tables show the qualitative (Table 1) and quantitative (Table 2) studies that were included. All 10 of the included studies were from English-speaking countries. Half were conducted in the United States,16, 32–35 three were from the United Kingdom36–38 and two from Australia.38, 40 More than half of the studies (n=6) recruited patients in the hospital setting,32, 34–36, 39, 40 one recruited subjects from both inpatient and home hospice16 and three recruited from community organizations such as a local interpreter chapter or local physician clinics.33, 37, 38

TABLE 1.

Summary of Qualitative Studies on the Use of Interpreters in Palliative Care

| Author (year), Location | Study Design | Objectives | N | Age (mean, range); Language of Patients/Families | Interpreter Type | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arriaza, et al (2011), Florida, U.S. | Exploratory online survey | To evaluate hospice bereavement services for Hispanics | 30 hospice bereavement coordinators | Range: 20–68; Spanish, English | Ad-hoc/bilingual staff, family members, professional interpreters |

|

| Davies, et al (2010), Northern California, U.S. | Semi-structured interviews | To evaluate experiences of families receiving pediatric palliative care | 36 LEP parents of pediatric patients at the end of life | Mean: 34.4; Range: 18–64; Cantonese, Mandarin, Spanish | Ad-hoc/bilingual staff, language concordant physicians |

|

| Kai, Beavan and Faull (2011), West and East Midlands regions of the U.K. | Focus groups | To evaluate experiences of health professionals caring for cancer patients from various ethnicities | 106 health professionals | Range: 24–65; Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi, Mirpuri, Sylheti, Bengali, Cantonese, Mandarin, African, French, German, Spanish, Italian | Professional interpreters, ad-hoc/bilingual staff, language concordant physicians, family members |

|

| Norris, et al (2005), Seattle, Washington, U.S. | Focus groups | To evaluate how to approach discussions between LEP patients and clinicians about end of life care | 43 professional interpreters in original focus group, 25 professional interpreters in validation focus group | Mean: 49 original and 51 validation; Range: 39–55 original and 40–58 validation; Cambodian, Cantonese, Mandarin, Spanish, Russian, Vietnamese | Professional interpreters |

|

| Randhawa, et al (2003), Luton, England, U.K. | In-depth interviews | To evaluate the under-utilization of palliative care services in ethnic minorities | 12 patients/family members, 10 health professionals | Range: 18–60 patients/family members; Urdu, Punjabi, Gujarati | Professional interpreters, family members |

|

| Spruyt & MacCallum (1999), Tower Hamlets, England, U.K. | Semi structured interviews | To evaluate palliative care experiences of the Bangladeshi community and their caregivers | 18 patients and 18 caregivers | Mean: Males 55, Females 40; Range: Males 34–65, Females 28–57; Sylheti (dialect of Bengali region) | Professional interpreters, language concordant clinicians, family members |

|

TABLE 2.

Summary of Quantitative Studies on the Use of Interpreters in Palliative Care

| Author (year), Location | N | Age (mean, range; SD); Language | Comparison Group; Interpreter Type | Outcomes | Results Related to Interpreter Use | Downs and Black Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butow, et al (2013), New South Wales, Australia | 32 LEP with interpreter, 15 LEP w/o interpreter | Median: 65 (LEP with interpreter) and 60 (LEP w/o interpreter); Chinese, Arabic, Greek | English-speaking persons vs. LEP persons w/interpreter vs. LEP persons w/o interpreter; family, bilingual staff, professional interpreters in person and via phone | (1) Impact of interpreters on prognosis/diagnosis discussions(br)(2) Characterize the behavior of oncologists during prognostication |

|

18 (good) |

| Chan & Woodruff (1999), Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia | 106 English speaking patients, 24 LEP patients | Median: 65 (English Speakers) and 69 (Non-English Speakers); Greek, Mandarin, Spanish, Italian, Yugoslavian, Lebanese, Vietnamese, Turkish, Polish | LEP persons w/interpreter vs. English-speaking persons; Family, bilingual staff, professional interpreters | (1) Impact of interpreters on prognosis/diagnosis discussions (2) Quality of symptom management at end of life |

|

20 (very good) |

| Pham et al (2008), Seattle, Washington, U.S. | 70 family members, 9 physicians, 10 nurses, and 26 other health professionals | Mean (SD): Family 33 (9.1), physicians 32, (4.1), nurses 34 (5.8), other clinicians 39, (12.2); Cambodian, Korean, Mandarin, Somali, Spanish, Russian, Vietnamese, Hmong | LEP persons with interpreter; Professional interpreter | (1) Measurement of accuracy of interpretation during family conferences at end of life |

|

15 (good) |

| Thornton et al (2009), Seattle, Washington, U.S. | 70 family members (interpreted conferences) 214 (non-interpreted conferences) | Mean (SD) of LEP group: patients 66 (17.9), family 33 (9.1), physicians 32 (4.1). English-speaking group: patients 60 (20.3), family 48 (15.8), physicians 38 (9.5); Cambodian, Korean, Somali, Spanish, Chinese, Hmong, Vietnamese, Russian | LEP persons w/interpreter vs. English-speaking persons; Trained interpreters | (1) Evaluate quality of clinician-family communication with LEP family members during ICU family conferences |

|

17 (good) |

Of the studies included, only two reported the type of training the interpreter had received33, 34 and, of these, only one reported whether the interpreter’s language skills were assessed.34 One study33 reported that all interpreters had 40 hours of training to become a medical interpreter and also participated in quarterly educational opportunities. The second study34 reported that interpreters were eligible to participate if they had passed the required state interpreter examination and thus, were certified professional medical interpreters. Among the articles, seven mostly focused on communication and comprehension of information32, 34–36, 38–40 and three on utilization of interpreters when providing palliative services.16, 33,37

The majority of studies (n=6)34, 35, 37–40 focused on the presence of interpreters in goals of care discussions, including code status and establishing a surrogate decision maker. Four of these studies also involved interpreters assisting with delivery of prognostic or diagnostic information32, 35, 36, 40 and one measured patient understanding of prognosis.39 Two articles38, 40 evaluated symptom management of cancer patients.

There were different populations focused upon in the studies: patients and/or their family members, clinicians, and interpreters. One study targeted clinicians caring for LEP cancer patients36 and two evaluated the practices of interpreters working with LEP patients at the end of life.16, 33 Two studied LEP patients and their families to evaluate their experiences receiving palliative care.32, 40 The remaining five34, 35, 37, 38, 40 focused on the experiences of patients, families and clinicians when palliative services are provided using professional interpreters.

Type of Interpreter

Only one study was set in a place that did not have professional interpreters available for daily care and the study reported that LEP families were not notified of the availability of professional interpreters.32 The remaining nine articles were conducted in settings where both professional interpreters and a variety of ad hoc interpreters were available. Five concluded that professional interpreters were not utilized adequately, based on their findings.33, 34, 36, 37, 39 A majority of the articles (n=6) found that providers relied on family, including minors, to interpret important information about diagnosis and prognosis.16, 36–40 In one of these, children were used as interpreters by eight different families studied, which led to burn out, maladaptive behavior, and truancy within the families.38 Another study demonstrated that family members were frequently being asked to interpret during bereavement counseling in the hospice setting.16 These studies concluded that having family members interpret was suboptimal because it led to poor communication and negative outcomes, including omission or alteration of information and emotional conflicts within the patient’s family.16, 32, 36–40

Effects Related to Interpreter Use

Overall, the studies found that professional and bilingual staff interpreters improved quality of care for LEP patients receiving palliative services. One study showed that language barriers for Spanish-speaking patients influenced their access to hospice services, particularly bereavement care for their family members.16 In the same study, the majority (54%) of hospice bereavement coordinators surveyed acknowledged that more interpreter services were needed to provide comprehensive bereavement services to LEP families. One study suggested that the disparity between the amount of time that clinicians spend speaking with LEP families compared to English-speaking families implies that the LEP families receive less information.35 Several other studies demonstrated that, in the absence of professional interpreters, LEP patients reported worse pain and non-pain symptom management and their family members lacked understanding of the patient’s clinical information, including prognosis or diagnosis, and experienced increased stress about the patient’s clinical situation.32, 36–40

Three studies recommended that providers and professional interpreters have brief meetings prior to interacting with LEP patients to clarify topics to be discussed, terminology to be used, or if strict interpretation vs. additional cultural mediation is needed to improve communication during interpretation.33, 34, 35 Other studies focused on the importance of defining a clear role for the interpreter prior to family discussions about end of life to improve communication.34, 35 One of these studies found that clinicians demonstrated aspects of communication that conveyed support and concern during end-of-life conversations less frequently with LEP families because of the emotional and informational complexity of these family conferences.35 The majority (7/10) of studies concluded that improving access to and/or standardizing utilization of professional interpreter services could improve the quality of care provided to LEP patients at the end of life.33–37, 39, 40

Study Appraisal

All quantitative studies had either a good or very good score on the modified Downs & Black checklist. The average Downs and Black score for quantitative articles was 17.5, which has been categorized in previous literature as “good.”29, 30 There was little variability in the Downs and Black scores, which ranged from 15–20 points. All of the studies had relatively small sample sizes and none of the studies were randomized controlled trials. All quantitative studies were cross-sectional. All qualitative studies were appraised as having credible findings. All of the qualitative studies addressed their original aims, justified their research designs, stated clearly how sampling and exclusion were conducted and adequately documented their research processes. Confidentiality and/or informed consent also were discussed in all of these studies. The qualitative studies all discussed their scope for drawing a wider inference and noted that the conclusions were not generalizable, as is the case with qualitative studies. Only one study did not clearly describe how data were analyzed.38

Discussion

This review found a small number of studies that have assessed the use of interpreters for LEP patients at the end of life. The majority of the existing literature on palliative care for LEP patients comprises case studies, needs assessments, and descriptive studies. Studies that assess the impact of interpreter use on quality of family meetings, symptom management at the end of life and access to hospice services are lacking. Despite the large body of literature that demonstrates the positive impact professional interpreters have on the health care outcomes of LEP patients4, 19, 20, 21 and the detrimental impact that ad hoc interpreters can have,4, 20, 21, 24, 25, 42 our review showed that ad hoc interpreters commonly interpreted in palliative care. Family members were often used as interpreters to deliver information about prognosis, diagnosis, and assess symptom management for LEP patients at the end of life.16, 36–40 Particularly concerning was the frequency with which family members and, in one study,38 children functioned as interpreters to facilitate end-of-life discussions. We also found that studies in the palliative care setting did not provide information on interpreters’ training nor on whether the interpreter’s English or non-English language skills were assessed. Several studies emphasized the importance of involving professional interpreters in discussions before patient interactions.33–35 The studies in this review incorporated the perspectives of patients, their family members, clinicians, and professional interpreters to provide a clearer understanding on how to approach end-of-life issues with LEP patients.

Research demonstrates that family members who interpret in the medical setting bring their own agendas and can become overwhelmed or uncomfortable by sensitive discussions such as death and dying.41–44 Moreover, compared to family members, fewer clinically significant errors in interpretation are found when professional interpreters are used.19, 45, 46 The CLAS Standards discourage the use of family members or friends as interpreters and prohibit the use of minors as interpreters, as do most health care facilities. This is a critical patient safety issue that should not be ignored; some health care facilities have been sued for malpractice related to significant injury when family members were involved in poor communication.47 Federal regulations and many states require the provision of language services for LEP patients.48 Lack of enforcement of these regulations, limited resources, and lack of awareness from health care providers about the importance of using professional interpreters help explain the underutilization of professional interpreters in the care of LEP patients at the end of life.49, 50

The amount of training interpreters undergo is an important factor to consider when discussing prognosis, diagnosis or goals of care, and is understudied.4, 51 One study assessed the experiences of professional interpreters in end-of-life discussions and found that although most of the interpreters surveyed had experience and felt comfortable with end-of-life discussions, only half reported that these discussions usually went well.52 This suggests that end-of-life discussions may be perceived as suboptimal by professional interpreters. Specific physician and interpreter behaviors such as cultural sensitivity, establishing trust, and effective communication skills are important determinants of how interpreters view the quality of these interactions,33, 52 which can influence the quality of end-of-life communication with LEP patients and their families. There is a lack of research on how interpreter training and physician or interpreter behaviors influence patient and family satisfaction and understanding during language discordant end-of-life discussions.

Our findings suggest that poor communication can be improved when providers establish a clear role for the professional interpreter and discuss the objectives of the patient interaction. Research has demonstrated that health care providers who are unfamiliar with the roles of professional interpreters and how to access them were less likely to use interpreters with LEP patients.19, 46, 53 A majority of interpreters in one study reported feeling that physicians needed more training on how to conduct end-of-life discussions through an interpreter.52 Studies support the need to improve health care professionals’ understanding of the role of professional interpreters to improve the quality of communication for LEP patients.53–55 Involving interpreters in discussions about the objectives of the patient encounter, including clarifying terminology, can improve the quality of the interaction between providers, interpreters, LEP patients, and their family members. Incorporating education on end-of-life discussions with LEP patients into clinician training programs is essential and currently lacking.2, 52, 56–58

A lack of understanding of LEP patients’ perspectives and how culture impacts the way illness is viewed can lead to misunderstandings and communication problems during family meetings.59–61 Assessing how palliative care needs differ by language and culture is another important gap in the literature.

This review is not without limitations. First, most of the included studies were either qualitative, had a small sample size, or were conducted at a single site, which limits the generalizability of the studies to patients from other settings, languages, countries or clinical contexts. However, the findings of both the quantitative and qualitative studies included were consistent with previous literature, which demonstrated that incorporating professional interpreters, rather than ad hoc interpreters, into clinical care can improve the quality of care for LEP patients.4 Second, many of the quantitative studies did not control for confounders such as race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, which also could have impacted LEP patients’ interactions with professional interpreters. Third, the majority of the studies did not report the type of training received by interpreters, which could correlate to the quality of communication. In the absence of this information, it is difficult to assess the true impact of the interventions described.

Conclusion

Palliative care physicians need to have an increased awareness of the growing LEP population in the U.S.62, 63 as language differences can impact patients’ and families’ understanding of prognosis, medical decision-making and goals of care during family meetings. This literature review highlights the importance of appropriate, compassionate and supportive communication with LEP patients facilitated through professional interpreters if the provider does not speak the patient’s language. Palliative care clinicians must learn to avoid the use of ad hoc interpreters, especially family members, and how to work with professional interpreters. Best practices by palliative care clinicians may include having a meeting with the interpreter prior to the patient interaction for clarification of the agenda, defining the role of team members, debriefing with interpreters to provide support and improve interpreter and clinician satisfaction and being aware of how language and culture influence patient decision-making. Further research is needed to evaluate if these practices influence the quality of communication with LEP patients and families and the impact of professional interpreters on improving goals of care discussions, symptom management, and emotional support for LEP patients and their families. The field of palliative medicine needs to move forward with more systematic, high-quality clinical research in order to improve the quality of end-of-life care for LEP patients.

Acknowledgments

No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ryan C. Language use in the United States: 2011 American Community Survey Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; 2013. Available at: www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/acs-22.pdf. Accessed September 9, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalabian J, Dunnington G. Impact of language barrier on quality of patient care, resident stress, and teaching. Teaching & Learning in Medicine. 1997;9:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs E, Chen AH, Karliner LS, Agger-Gupta N, Mutha S. The need for more research on language barriers in health care: a proposed research agenda. Milbank Q. 2006;84:111–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karliner L, Jacobs E, Chen A, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carasquillo O, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, Burstin HR. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an Emergency Department. J General Intern Med. 1999;14:82–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Baez L, Loehrer P, Pandya KJ. Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:813–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured. Med Care. 2002;40:52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonham VL. Race, ethnicity and pain treatment: striving to understand the cause and solutions to the disparities in pain treatment. J Law Med Ethics. 2001;29:52–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2001.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Mendoza TR, et al. Dimensions of the impact of cancer pain in a four country sample: new information from multidimensional scaling. Pain. 1996;67:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagawa-Singer M, Blackhall LJ. Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: you got to go where he lives. JAMA. 2001;286:2993–3001. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. (3rd) 2013 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.611. Available at: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/Guidelines_Download2.aspx. Accessed September 7, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Carrion IV. End of life issues among Hispanics/Latinos: studying the utilization of hospice services by the Hispanic/Latino community. Graduate School Theses and Dissertations. 2007 Available at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/657. Accessed June 28, 2014.

- 14.Randall H, Csikai E. Issues affecting utilization of hospice services by rural Hispanics. J Ethnic Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2003;12:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Born W1, Greiner KA, Sylvia E, Butler J, Ahluwalia JS. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about end-of-life care among inner-city African Americans and Latinos. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:247–256. doi: 10.1089/109662104773709369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arriaza P, Martin SS, Csikai EL. An assessment of hospice bereavement programs for Hispanics. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2011;7:121–138. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.593151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer Y, Rotem B, Alsana S, Shvartzman P. Providing culturally sensitive palliative care in the desert: the experience, the needs, the challenges, and the solution. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr SE, Roberts RP, Dufour A, Steyn D. The critical link: Interpreters in the community. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Co.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics. 2003;111:6–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:255–299. doi: 10.1177/1077558705275416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, et al. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional vs. ad-hoc vs. no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Minority Health. The national CLAS standards in health care. 2013 Available at: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15#sthash.MeVMxQce.dpuf. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- 23.National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. National standards for healthcare interpreter training programs. 2011 Available at: http://www.ncihc.org/assets/documents/publications/National_Standards_5-09-11.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 24.Lee LJ, Batal HA, Maselli JH, Kutner JS. Effect of Spanish interpretation method on patient satisfaction in an urban walk-in clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:641–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diamond LC, Wilson-Stronks A, Jacobs EA. Do hospitals measure up to the national culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards? Med Care. 2010;48:1080–1087. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f380bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehin R, Burnett RS, Brasher PM. Does the new generation of high-flex knee prostheses improve the post-operative range of movement? A meta-analysis J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1429–1434. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.23199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 suppl):101S–156S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naylor K, Ward J, Polite BN. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer L, Britain G. Quality in qualitative evaluation: a framework for assessing research evidence. London, UK: Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office, Cabinet Office; 2003. Available at: http://www.civilservice.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/a_quality_framework_tcm6-38740.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies B, Contro N, Larson J, Widger K. Culturally-sensitive information-sharing in pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e859–e865. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norris WM, Wenrich MD, Nielsen EL, et al. Communication about end-of-life care between language-discordant patients and clinicians: insights from medical interpreters. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1016–1026. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pham K, Thornton JD, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR. Alterations during medical interpretation of ICU family conferences that interfere with or enhance communication. Chest. 2008;134:109–116. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR. Families with Limited English Proficiency receive less information and support in interpreted ICU family conferences. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:89–95. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181926430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kai J, Beavan J, Faull C. Challenges of mediated communication, disclosure and patient autonomy in cross-cultural cancer care. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:918–924. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Randhawa G, Owens A, Fitches R, Khan Z. Communication in the development of culturally competent palliative care services. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2003;9:24–31. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2003.9.1.11042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spruyt O. Community-based palliative care for Bangladeshi patients in east London. Accounts of bereaved carers. Palliat Med. 1999;13:119–129. doi: 10.1191/026921699667569476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butow PN, Sze M, Eisenbruch M, et al. Should culture affect practice? A comparison of prognostic discussions in consultations with immigrant versus native-born cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan A, Woodruff RK. Comparison of palliative care needs of English and non-English speaking patients. J Palliat Care. 1999;15:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green J, Free C, Bhavnani V, Newman T. Translators and mediators: bilingual young people’s accounts of their interpreting work in health care. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2097–2110. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobs B, Kroll L, Green J, David TJ. The hazards of using a child as an interpreter. J R Soc Med. 1995;88:474–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orellana MF. Responsibilities of children in Latino immigrant homes. In: Suarez-Orozco C, Todorova ILG, editors. Understanding the social worlds of immigrant youth. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weisskirch RS. Feelings about language brokering and family relations among Mexican American early adolescents. J Early Adolescence. 2007;27:545–561. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prince D, Nelson M. Teaching Spanish to emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith AK, Sudore RL, Perez-Stable EJ. Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: whenever we prayed, she wept. JAMA. 2009;301:1047–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen AH, Youdelman MK, Brooks J. The legal framework for language access in healthcare settings: Title VI and beyond. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):362–367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0366-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.United States Department of Justice. Guidance to federal financial assistance recipients regarding Title VI prohibition against national origin discrimination affecting Limited English Proficient persons. Federal Register. 2002;67(117):41455–41472. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones D. Should the NHS curb spending on translation services? BMJ. 2007;334:399. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39126.572431.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ku L, Flores G. Pay now or pay later: providing interpreter services in health care. Health Aff. 2005;24:435–444. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lorenz KA, Ettner SL, Rosenfeld KE, et al. Accommodating ethnic diversity: a study of California hospice programs. Med Care. 2004;42:871–874. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135830.13777.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Kerr K, O’Riordan D, Pantilat SZ. Interpretation for discussions about issues: results from a National Survey of health care interpreters. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:1019–1026. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kai J, Briddon D, Beavan J. Valuing diversity: A resource for health professional training to respond to cultural diversity. 2nd. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2006. Working with intepreters and advocates; pp. 201–224. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schenker Y, Smith AK, Arnold RM, Fernandez A. Her husband doesn’t speak much English: conducting a family meeting with an interpreter. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:494–498. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bischoff A, Perneger TV, Bovier PA, Loutan L, Stalder H. Improving communication between physicians and patients who speak a foreign language. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:541–546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fischer SM, Sauaia A, Min S, Kutner J. Advance directive discussions: lost in translation or lost opportunities? J Palliat Med. 2012;15:86–92. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobs EA, Diamond LC, Stevak L. The importance of teaching clinicians when and how to work with interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;78:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schroder C, Heyland D, Jiang X, et al. Educating medical residents in end-of-life care: insights from a multicenter survey. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:459–470. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaufert J, Putsch RW, Lavallee M. End-of-life decision making among Aboriginal Canadians: interpretation, mediation and discord in the communication of bad news. J Palliat Care. 1999;151:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaufert J, Putsch RW. Communication through interpreters in health care: ethical dilemmas arising from differences in class, culture, language and power. J Clin Ethics. 1997;8:7–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaufert J, Putsch RW, Lavallee M. Experience of Aboriginal health interpreters in mediation of conflicting values in end-of-life decision making. Int J Circumpolar Health. 1998;57(Suppl 1):43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shin HB, Kominski RA. American Community Survey Reports. U.S. Bureau of the Census; Language use in the United States: 2007. Available from: factfinder2.census.gov. Accessed November 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koenig BA, Gates-Williams J. Understanding cultural difference in caring for dying patients. West J Med. 1995;163:244–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]