Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a T helper type 2 (Th2) cytokine–associated disease characterized by eosinophil infiltration, epithelial cell hyperplasia and tissue remodeling. Recent studies have highlighted a major contribution for IL-13 in EoE pathogenesis. Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor (PIR)-B is a cell surface immune-inhibitory receptor that is expressed by eosinophils and postulated to regulate eosinophil development and migration. We report that Pirb is upregulated in the esophagus after inducible overexpression of IL-13 (CC10-Il13Tg mice) and is overexpressed by esophageal eosinophils. CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice displayed increased esophageal eosinophilia and EoE pathology, including epithelial cell thickening, fibrosis and angiogenesis, compared with CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice. Transcriptome analysis of primary Pirb+/+ and Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils revealed increased expression of transcripts associated with promoting tissue remodeling in Pirb−/− eosinophils including pro-fibrotic genes, genes promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and genes associated with epithelial growth. These data identify PIR-B as a molecular checkpoint in IL-13–induced eosinophil accumulation and activation, which may serve as a novel target for future therapy in EoE.

Keywords: eosinophils, inflammation, cytokines, allergy, esophagus

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an emerging inflammatory disease that is characterized by dominant eosinophilic inflammation, epithelial hyperplasia, collagen deposition and tissue fibrosis (1, 2).

Patients with EoE have increased esophageal expression of IL-13, and ex-vivo treatment of esophageal epithelial cells with IL-13 leads to dramatic gene expression alterations that are strikingly similar to those found in biopsies from patients with EoE (3). IL-13 is directly responsible for the induction of eosinophil-specific chemokines such as those belonging to the eotaxin family. Chronic induction of IL-13 in the lungs using a doxycycline-induced, clara cell 10 (CC10) promoter–regulated, IL-13 transgenic mouse model (CC10-Il13Tg), leads to experimental EoE with typical esophageal pathology including eosinophil accumulation, fibrosis, epithelial cell hyperplasia and angiogenesis (3, 4). Indeed, an anti–IL-13 therapeutic in patients with EoE markedly reverses the disease-specific transcriptome including markers of tissue remodeling and chemokine expression, proving the centrality of IL-13 induced response in EoE (5).

Although eosinophils likely promote EoE, pathways that limit eosinophil accumulation and/or activation in EoE are poorly defined. In fact, defining inhibitory checkpoints particularly in the settings of IL-13-driven inflammation has not been previously described. Accordingly, herein we aimed to define molecular pathways that regulate the activities of esophageal eosinophils with specific emphasis on inhibitory, immunoglobulin-like receptors, which provide counter-regulatory signals for various eosinophil activities (6) Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PIR-B) is a member of the immunoglobulin super family and is expressed mostly in a pair-wise fashion with PIR-A on the surface of myeloid cells including eosinophils (7, 8). PIR-B contains four immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIM), which are capable of binding intracellular phosphatases, such as SHP-1 and/or SHP-2, and subsequently suppress cellular activation elicited by PIR-A, cytokines, chemokines, Toll-like receptors and adhesion molecules (9–14). We have previously demonstrated that PIR-B is a negative regulator of eotaxin-induced eosinophil chemotaxis and recruitment, and that the PIR-A/PIR-B axis constitutes a critical role in eosinophil development (12, 14). Although these data suggest key functions for PIR-B in eosinophil-associated pathologies, the role of PIR-B in EoE has yet to be defined. Herein, we demonstrate a key inhibitory function for PIR-B in EoE pathogenesis; overexpression of IL-13 in Pirb−/− mice leads to exaggerated EoE including eosinophilic infiltration, epithelial cell thickening, fibrosis and angiogenesis. Our results demonstrate that eosinophil activities in EoE are intrinsically suppressed by PIR-B and that loss of PIR-B by eosinophils mediates increased experimental EoE pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

We generated bitransgenic mice (CC10-Il13Tg) in which Il13 was expressed in a lung-specific manner that allowed for external regulation of the transgene expression as previously described (4). This model was specifically chosen since we have previously shown that overexpression of IL-13 in the lungs induces esophageal disease resembling eosinophilic esophagitis(15). Male and female, 6- to 8-week-old Pirb−/− mice of generations >F9 were backcrossed to C57BL/6 (9). CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13/Pirb+/+ were generated by breeding the CC10-Il13Tg with Pirb−/− mice. For all experiments, littermates were used as controls. We induced Il13 transgene expression by feeding the CC10-Il13Tg mice doxycycline-impregnated food (DOX) (625 mg/kg; Purina Mills, Richmond, IN) for two weeks. Animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Real-time quantitative PCR

RNA samples from the whole esophagus were subjected to reverse transcription analysis using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed using the CFX96 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in conjunction with the ready-to-use fast-start SYBR Green I Master reaction kit (Roche Diagnostic Systems). Results were normalized to Hprt cDNA as previously described (16). The primers that were used in this study are as follows (5’ to 3’): Ccl11 (encodes to Eotaxin-1), forward CACGGTCACTTCCTTCACG and reverse GGGGATCTTCTTACTGGTA; Acta2 (encodes α-SMA), forward AGTCGCTGTCAGGAACCCTGAGAC and reverse CGAAGCCGGCCTTACAGAGCC; and Hprt, forward GTAATGATCAGTCAACGGGGGAC and reverse CCAGCAAGCTTGCAACCTTAACCA.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow, peripheral blood cells or enzymatically digested esophagus was conducted using the following antibodies: anti-CD11b (R&D), anti–GR-1 (BD Bioscience), anti–Siglec-F (BD Bioscience), anti-CCR3 (BD Bioscience), anti–PIR-A/B (ebioscience), IgG2b (ebioscience), anti-CD45 (ebioscience) and anti-CD11c (BD Bioscience). Cell counts were conducted using 123count beads (ebioscience) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. In all experiments, at least 50,000 events were acquired by (FACSCalibur, BD Bioscience), and data were analyzed using the Kaluza (BeckmanCoulter) or FlowJo (TreeStar) softwares.

PhosphoFlow

Total bone marrow cells were stained with anti-CD45 (ebioscience), anti–Siglec-F (BD Bioscience) and anti-CCR3 (BD Bioscience). The mature eosinophils (triple positive) were sort by MoFlo XDP (Beckman Coulter). The cells were activated with bronchoalvelolar lavage fluid (BALF) which was obtained from the lungs of CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice for the indicated time points (0, 5 and 10 minutes), and cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS and permeabilized using saponin-based permeabilization buffer (X1, invitrogen). Cells were stained with phospho-ERK1/2 (Cell signaling). Events were acquired by FACSCanto (BD Bioscience), and data were analyzed using the Kaluza (BeckmanCoulter) or FlowJo (TreeStar) software. For phosphoflow analysis, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each time point, in each biological repeat, was normalized to baseline and expressed as the fold change over baseline.

ELISA

IL-13 and CCL11 levels were assessed using commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, Duo Set), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The lower detection limits for IL-13 and CCL11 were 62.5 and 15.6 pg/mL, respectively.

Quantifying tissue eosinophils by MBP staining

Esophageal or lung eosinophils were detected using an immunohistochemical stain against murine eosinophilic major basic protein (MBP) as previously described (3). Quantification of positive cells was performed using Cell^A imaging software, and results were reported as immunoreactive cells per square millimeter.

Epithelial thickness and collagen quantification

Epithelial thickness was determined by staining cross-sectioned esophageal samples with MBP stain. Quantification of thickness was performed using Cell^A imaging software by taking 7-14 lengthwise measurements per slide from the lumen to the basement membrane of each esophagus. Collagen deposition was determined by staining esophageal samples with Masson's trichrome and quantified using Cell^A software. Collagen measurements are recorded as area of collagen staining per length of basement membrane as previous described (3).

Assessing angiogenesis

Tissues were fixed, embedded, sectioned, prepared and stained as previously described (3). Morphometry was used to determine the average number of CD31-positive vessels per high-power field in each group.

Affymetrix cDNA microarray

Mouse Affymetrix (CA, USA) microarrays (2.0 ST GeneChip®) were performed and analyzed using established protocols of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Gene Expression Core and according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analyzed using Genespring software with a fold-change cutoff of 2 (FC>2) and unpaired Student’s t test (P > 0.05). Heat plots and Venn diagrams were generated according to gene lists that were generated by GeneSpring software (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

Eosinophil depletion

CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13/Pirb+/+ mice were fed with DOX for two weeks. On days -1, 1, 4, 7 and 10, they were injected intraperitoneally with 20 μg soluble anti-mouse Siglec-F. Rat IgG2a was used as an isotype-matched control antibody (R&D Systems) (17). At day 14, the mice were sacrificed and the esophagus was analyzed for eosinophil levels using anti-MBP staining. Epithelial thickness, collagen deposition and acta2 transcript levels were determined as described above.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Student's t test or by ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test using GraphPad Prism 5. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Pirb is an IL-13–induced, eosinophil-associated gene in the esophagus

Pirb expression was increased in the esophagus following Il13 transgene induction (Figure 1A). To define the cellular source accounting for increased Pirb expression, polychromatic flow cytometric staining was conducted using single-cell suspensions of esophageal tissue. After overexpression of IL-13, eosinophils constituted the largest PIR-A/B+ cellular source in the esophagus, reaching nearly 40% of the entire CD45+ cellular population, whereas neutrophils and CD11C+/GR1− cell populations were ~7% and ~4%, respectively. Importantly, the second major CD45+ population, the lymphocyte population, comprising more than 15%, did not express PIR-A/B (Figure 1B, 1C and S1). Furthermore, among the CD45+ cell population, eosinophils expressed relatively high surface levels of PIR-A/B (Figure 1C). Notably, PIR-A/B expression in the esophagus was confined to the hematopoietic compartment since CD45− cells did not display PIR-A/B expression (Figure 1D). Interestingly, the expression of PIR-A/B in esophageal eosinophils was higher than that found on peripheral blood eosinophils (Figure 1E). Thus, increased expression of PIR-B in the esophagus, after IL-13 induction, is attributable to infiltration of inflammatory cells, especially eosinophils.

Figure 1. Expression of PIR-B in IL-13–induced experimental EoE.

The expression of Pirb was assessed by microarray analysis in the esophagus of CC10-Il13Tg mice after two weeks of doxycycline (DOX) or No DOX feeding (A); **P < 0.01 No DOX vs. DOX. In (B), flow cytometric analysis of the main cellular populations infiltrating the esophagus after IL-13 overexpression is shown. Analysis of PIR-A/B surface expression in various cell types after DOX treatment is shown (C). ΔMFI for PIR-A/B expression was calculated by subtracting the MFI obtained for anti-PIR-A/B staining with that obtained for the isotype control. Representative plot of PIR-B expression by esophageal CD45− cells is shown (D). Analysis of surface PIR-A/B expression in peripheral blood eosinophils and esophageal eosinophils is depicted (E). Data in (A), (B), (C) and (E) are represented as mean with standard error of mean (SEM). Data are from n = 3-5 mice for each group; **P < 0.01; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity.

PIR-B negatively regulates IL-13–driven esophageal eosinophilia

To define the role of PIR-B in IL-13–induced esophageal pathology, Pirb−/− mice were mated with CC10-Il13Tg mice to generate CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice. Thereafter, the mice were fed with DOX for 2 weeks, and eosinophil infiltration into the esophagus was determined. CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ displayed increased eosinophil accumulation in the esophagus as assessed by anti-eosinophil major basic protein (MBP) staining (Figure 2A–B) and flow cytometric analysis of CD45+/CD11b+/Siglec−F+/SSChi cells (Figure 2C). DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice displayed nearly a two-fold increase in the levels of esophageal eosinophilia in comparison with DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+mice (Figure 2D). This increase is impressive considering the already marked increased eosinophilia in the esophagus and lungs of CC10-Il13Tg mice (15). Moreover, the Pirb−/− eosinophil population was approximately 60% of the entire CD45+ cell population. Other examined CD45+ cell populations did not increase, which demonstrates that the inhibitory regulatory role of PIR-B in accumulation of CD45+ cells is specific to eosinophils (Figures 2E and S2). Increased eosinophil infiltration was not confined to the esophagus, as analysis of anti-MBP–stained lung specimens and differential cell counts of BALF cells reveled increased lung eosinophilia in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice in comparison with CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ (Figure S3). Furthermore, increased eosinophil infiltration into the esophagus and lungs of DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice was not due to alterations in IL-13 or eosinophil chemoattractant expression in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice since BALF and esophageal levels of IL-13 and CCL11 were similar in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice ((15) and Figure 2F–H).

Figure 2. Eosinophil levels in the esophagus of CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice.

CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice were treated with doxycycline (DOX) or No DOX for two weeks. Thereafter, the mice were sacrificed, and the esophageal tissue was taken for histology (A-B) or flow cytometric analysis (C). Representative photomicrograph (X400, A) and quantitation (B) of anti-eosinophil major basic protein (MBP) immunohistochemical stain is shown. Representative gating strategy (C) and quantification (D) assessing esophageal eosinophils from no DOX- and DOX-treated mice as determined by flow cytometry are shown. Flow cytometric analysis of the main cellular populations infiltrating the esophagus after IL-13 overexpression is shown (E). Lung and esophageal IL-13 (F) and CCL11 (H) protein expression as well as expression of esophageal Ccl11 transcript levels (G, fold over house keeping gene) are shown; Data are from 2-3 independent experiments in which n = 2 from each of the No DOX–treated group and n = 4 from each of the DOX-treated groups. Data in (B) and (D-H) are represented as mean with standard error of mean (SEM). NS, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

PIR-B inhibits the development of IL-13–induced esophageal pathology

The elevated levels of eosinophils in the esophagus of DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− suggested a possible role for PIR-B in regulating IL-13–induced esophageal pathology. Masson’s trichrome staining revealed increased areas of esophageal collagen deposition in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice (Figure 3A and 3B). Furthermore, qPCR analysis of the gene expression Acta2 (alpha smooth muscle actin, α-SMA), a prototype marker of myofibroblasts, revealed substantially increased Acta2 expression in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice (Figure 3C). Moreover, assessment of esophageal epithelial cell thickening revealed that DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− had a significantly increased epithelial cell layer thickness (Figures 3D). Assessing IL-13–induced blood vessel formation using anti-CD31 staining demonstrated greater vessel size (Figure 3E) and quantity (Figure 3F) in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice than in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice.

Figure 3. Esophageal tissue remodeling in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice.

CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice were treated with doxycycline (DOX) or No DOX for two weeks. Thereafter, the mice were sacrificed, and the esophageal tissues were obtained. Representative photomicrographs of Masson's trichrome (X400) (A) and morphometric and quantitative analysis of collagen deposition (B) are shown. α-smooth muscle actin gene expression (Acta2) in the esophagus was determined by quantitative PCR analysis and normalized to the housekeeping gene Hprt (C). Quantitative analysis of epithelial cell thickness is shown (D). Morphometric (E) and quantitative (F) analysis of anti–CD31 stain are shown. Data were obtained from 3 independent experiments from at least n = 4 mice for each group. Data in (B-D) and (F) are represented as mean with standard error of mean (SEM). *P < 0.05.

PIR-B inhibits IL-13 induced eosinophil dependent collagen deposition and angiogenesis

We hypothesized that PIR-B inhibits IL-13-mediated eosinophil-dependent increased tissue remodeling as seen in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/−. To examine this hypothesis we injected anti siglec-F specific antibodies, which are known to induce eosinophil apoptosis (17, 18) and monitored esophageal pathology. Anti-Siglec-F treatment resulted in complete depletion of esophageal eosinophils in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice (Figure S4). If the worsened pathology in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice was dependent on the expression of PIR-B in eosinophils, then depletion of eosinophils in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice should result in similar severity of pathology as in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice. Indeed, assessment of esophageal pathology in eosinophil depleted DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice revealed that in the absence of eosinophils, CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice displayed similar pathology in terms of collagen deposition and angiogenesis (as revealed by Masson’s trichrome staining and anti-CD31 staining) (Figure 4A–D). Notably, eosinophil depletion did not prevent the increased epithelial thickness and the increased Acta2 expression in DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice indicating that PIR-B may regulate the activities of additional non-eosinophil cells that are responsible for these aspects of tissue remodeling (Figure 4E–G).

Figure 4. Eosinophil dependent esophageal tissue remodeling in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice.

CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice were treated with doxycycline (DOX) for two weeks. On days -1, 0, 1, 4, 7 and 10, anti-siglec F (or suitable isotype control) were injected to the intra peritoneal cavity. On day 14 the mice were sacrificed, and the esophageal tissues was obtained. Representative photomicrographs of Masson's trichrome (X400) (A) and anti-CD31 stain (C) as well as quantitative analysis of collagen deposition (B) and number of blood vessels in the esophagus are shown (D). Expression of α-smooth muscle actin (Acta2) in the esophagus was determined by quantitative PCR analysis and normalized to the house-keeping gene Hprt (E). Data are from n = 5-6 mice for each group; Data in (B, D, F and G) are represented as mean with standard error of mean (SEM). *P < 0.05.

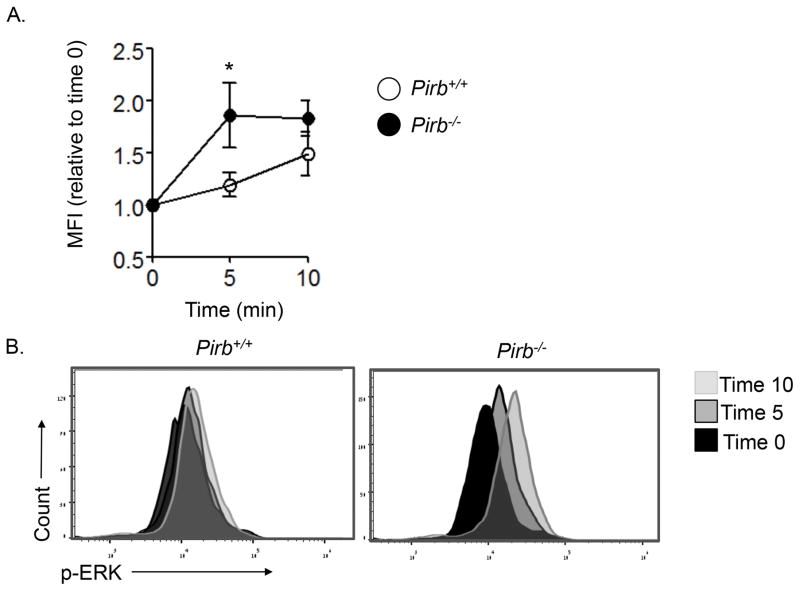

PIR-B inhibits IL-13–mediated eosinophil activation

We hypothesized that PIR-B may serve as an intrinsic inhibitor of eosinophil activation in the esophagus. To assess this possibility, we examined the activation (i.e. phosphorylation) status of ERK in eosinophils (as a surrogate marker for eosinophil activation) in response to the inflammatory milieu, which is elicited by IL-13. To this end, naïve primary eosinophils were sorted from the bone marrow of CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice. Thereafter, the cells were activated with BALF that was obtained from the lungs of DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice. Eosinophils that were activated with BALF that was obtained from the lungs of CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice had readily detectable phosphorylation of ERK (~1.25 -fold increase over baseline). In contrast, activation of Pirb−/− eosinophils results in substantially greater ERK phosphorylation (~1.9-fold increase over baseline, Figure 5) than activation of Pirb+/+ eosinophils. These data demonstrate that PIR-B is an intrinsic negative regulator of eosinophil activation in response to the IL-13–induced microenvironment.

Figure 5. The role of PIR-B in eosinophil activation in response to the esophageal microenvironment.

Primary naïve mature (i.e. CD45+/CCR3+/Siglec-F+/SSChi) bone marrow eosinophils were sorted from CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice and activated with bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from DOX-treated CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice for the indicated time points. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was determined by phosphoflow analysis. Kinetic (A) and histogram overlay (B) are shown. Data are from n = 4 mice for each group; *P < 0.05 MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; p-, phosphorylated.

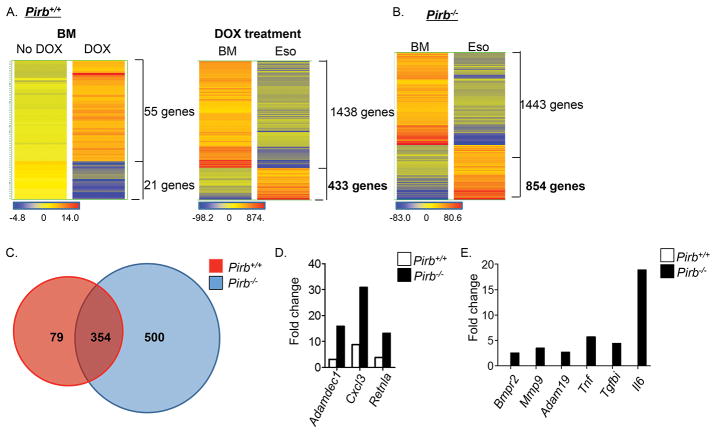

PIR-B negatively regulates IL-13–induced esophageal eosinophil effector functions

Next, we aimed to define the transcriptome signature of Pirb+/+ and Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils. To this end, microarray analysis was performed on primary eosinophils that were sorted from the bone marrow and esophagus of DOX-treated CC10- Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice (the complete data set can be found at URL- https://urldefense.proofpoint.com/v2/url?u=http-3A__www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov_geo_query_acc.cgi-3Facc-3DGSE81135&d=CwIEAg&c=P0c35rBvlN7D8BNx7kSJTg&r=Wbplm55465PTVxk38uHqNel33xEvQShf2js8ewQtSZ4&m=Hh2gtDH_Et_b1oiQJXB6FcZvlJK2NcsM6yZwymATiW0&s=tCTO_VreVqqw5A_nAKJUwTRyFMajG_yLWTqRXRT4aow&e= accession number: GSE81135).

First, we aimed to determine whether local over expression of IL-13 exerts any systemic effects in bone marrow eosinophils. Elevated expression of IL-13 resulted in modest effects in Pirb+/+ bone marrow eosinophils, as IL-13 induced alteration of 76 genes (55 upregulated genes and 21 downregulated genes; Figure 6A and gene lists 1-2 online). In contrast, IL-13 induced marked alterations in Pirb+/+ esophageal eosinophils (Figure 6A), as this was an ~8-fold increase in the total amount of upregulated genes in esophageal (433 genes) compared to bone marrow eosinophils (Figure 6A and gene lists 3–4 online). These genes include multiple cell surface receptors including cytokine and chemokine receptors (e.g. Ccrl2, Il1r2, Ccr1 and Csf2rb2); immunoglobulin-like receptors (e.g. Lilrb3/Pirb, Lilra6/Pira, Cd300lf, Cd300ld, Cd300lb and Gp49a); and cell adhesion and migration molecules (e.g. Cd44, Itga2 and Itga4). In addition, various enzymatic pathways (e.g. Ptgs2, Ear11, Adam8 and Mmp25) and secreted factors such as cytokines (e.g. Il1a, Il1b and Il4), chemokines (e.g. Cxcl2, Ccl3, Ccl2, Ccl4 and Csf1) and pro-fibrogenic molecules (e.g. Rentla, Retnlg, Postn and Tnfaip3) were upregulated. Moreover, IL-13 altered the expression of numerous intracellular signaling molecules (e.g. MAPK pathway [Mapk6, Mapkapk2 and Mapk1ip1], JunB, Nfkb pathway [Nfkbiz, Nfkbia and Nfkbie] and transcription factors [C/EBPβ]). Finally, IL-13 induced a pronounced effect on expression of Pirb+/+eosinophil microRNAs (e.g. Mir21, Mir1931 and Mir146b), cell cycle–related molecules (e.g. G0S2, cyclinG2, Gadd45a, S100a10 and S100a4) and survival molecules (e.g. Bcl2l11and Fas) (see Table I). Collectively, these data suggest a profound impact of IL-13 on esophageal eosinophils in the presence of PIR-B.

Figure 6. Gene expression profile in esophageal eosinophils after IL-13–induced experimental EoE.

CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice were treated with doxycycline (DOX) or No DOX for two weeks. Thereafter, the mice were sacrificed, and eosinophils were sorted from the esophagus (Eso) and bone marrow (BM) and subjected to microarray analysis. Heat plot analysis comparing Pirb+/+ BM eosinophils from No DOX- and DOX-treated mice is shown (A, left panel). In addition, heat plot analysis of DOX-treated BM and esophageal Pirb+/+ eosinophils (A, right panel) and Pirb−/− eosinophils (B) is shown. Venn plot analysis performed on the upregulated genes of DOX-treated esophageal Pirb+/+ and Pirb−/− eosinophils is shown (C). Representative genes that were upregulated in esophageal eosinophils compared to bone marrow eosinophils from both CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice are shown (D). Representative genes that were exclusively upregulated in esophageal eosinophils compared to bone marrow eosinophils from CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice are shown. Data are shown for n = 3 mice from each group with inclusion criteria of P > 0.05 and fold change > 2.

Table I.

Genes of interest that were upregulated in eosinophils in the esophagus compared to the bone marrow of CC10Il13Tg/Pirb+/+mice

| Gene symbol | Fold change [Esophagus/Bone marrow] | |

|---|---|---|

| Surface molecules | Ccrl2 | 29.3 |

| Gp49a | 16.1 | |

| Il1r2 | 6.97 | |

| Cd300ld | 6.36 | |

| Ccr1 | 3.38 | |

| Cd300lf | 3.22 | |

| Cd300lb | 2.96 | |

| Lilrb3 | 2.90 | |

| Lilra6| | 2.79 | |

| Csf2rb2 | 2.78 | |

| Cell adhesion and migration molecules | Itga2 | 3.07 |

| Itga4 | 2.75 | |

| Cd44 | 2.61 | |

| Enzymes | Ptgs2 | 74.8 |

| Ear11 | 50.7 | |

| Adam8 | 6.42 | |

| Mmp25 | 2.54 | |

| Secreted factors | Il1a | 34.9 |

| Il1b | 21.0 | |

| Cxcl2 | 20.8 | |

| Tnfaip3 | 15.6 | |

| Ccl3 | 11.8 | |

| Ccl2 | 5.76 | |

| Retnlg | 5.43 | |

| Il4 | 5.40 | |

| Retnla | 3.87 | |

| Postn | 3.60 | |

| Csf1 | 2.59 | |

| Ccl4 | 2.08 | |

| Intracellular signal molecules | Nfkbiz | 7.63 |

| Nfkbia | 3.47 | |

| Nfkbie | 2.44 | |

| Mapkapk2 | 2.30 | |

| Junb | 2.30 | |

| Cebpb | 2.27 | |

| Mapk6 | 2.24 | |

| Mapk1ip1 | 2.06 | |

| MicroRNA | Mir1931 | 16.8 |

| Mir146b | 3.64 | |

| Mir21 | 2.75 | |

| Cell cycle molecules | G0s2 | 7.09 |

| Ccng2 | 4.75 | |

| S100a4 | 3.72 | |

| Gadd45a | 3.50 | |

| S100a10 | 2.61 | |

| Survival molecules | Bcl2l11 | 6.59 |

| Fas | 5.83 |

Although there was a dramatic effect of IL-13 on (Pirb+/+), eosinophils primary esophageal eosinophils in the absence of PIR-B (sorted from CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice) displayed a substantially hyperactivated phenotype in comparison to esophageal eosinophils in the presence of PIR-B (sorted from CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+ mice) when adjusted for bone marrow expression (Figure 6B vs. 6A right panel). For example, Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils showed induction of nearly 2-fold more genes than did Pirb+/+ esophageal eosinophils (854 genes in Pirb−/− cells vs. 433 genes Pirb+/+ cells) (Figure 6A, 6B and gene lists 5-6). Importantly, altered gene expression in Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils was not due to systemic effects of IL-13 since Pirb−/− bone marrow eosinophils from CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice showed minimal gene alterations after induction of IL-13 (list 7–8 online) and these alterations were similar to those observed in Pirb+/+ cells.

Analysis of the 854 genes that were induced in Pirb−/− eosinophils revealed that the majority of the genes that were induced in wild-type esophageal eosinophils (354 out of 433 genes, comprising 82% of the IL-13–activated esophageal eosinophil transcriptome) were also upregulated in Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils (Figure 6C and gene list 9 online). Importantly, among these 354 common genes, 30 were found to be upregulated more than 2 fold in Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils, including various surface molecules (e.g. Ccr1 and Lilra6), enzymes (e.g. Adamdec1 and Pla2g7), secreted factors (e.g. Retnla, Cxcl3 and Csf1) and intracellular signal molecules (e.g. Btg2 and Irg1) (Figure 6D, Table II and gene list 10 online).

Table II.

Genes of interest that were upregulated in eosinophils of the esophagus compared to the bone marrow of both CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb+/+and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice

| Gene symbol | Pirb+/+ | Pirb−/− | Fold change [Pirb−/− / Pirb+/+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adamdec1 | 3.15 | 16.0 | 5.08 |

| Btg2 | 5.44 | 22.0 | 4.03 |

| Cxcl3 | 8.84 | 30.9 | 3.49 |

| Retnla | 3.87 | 13.3 | 3.43 |

| Irg1 | 13.2 | 41.9 | 3.17 |

| Csf1 | 2.59 | 7.53 | 2.91 |

| Pla2g7 | 4.20 | 9.90 | 2.36 |

| Ccr1 | 3.38 | 7.92 | 2.34 |

| Lilra6 | 2.79 | 6.46 | 2.31 |

Further analysis revealed that Pirb−/−esophageal eosinophils displayed a distinct genetic signature involving an exclusive upregulation of 500 additional genes (gene list 11 online). These genes included cell surface molecules such as cytokine receptors (e.g. Il5ra, Il12rb2, Ifnar1 and Bmpr2), inhibitory receptors (e.g. Cd300a) and cell adhesion and migration molecules (e.g. Itgax, Itgb3, Itgal, Ezr, acta1, Vasp and Cd24) (Figure 6E). In addition, gene expression of various enzymatic pathways (e.g. Mmp9, Capn2 and Adam19), secreted factors (e.g. Il6, Tnf, Cxcl10, Tgfbi, Areg and Ccl8) and receptors (e.g. Notch1 and Notch2) that have been linked with tissue fibrosis was increased in Pirb−/− eosinophils (Figure 6E). Moreover, gene expression of intracellular signaling molecules, including key molecules of the IL-4/IL-13 signaling pathway (e.g. Stat6, JAk2), NFκB signaling pathway (e.g Nfkb2, /Rela, Nfkbib) and signaling pathways that are involved in healing responses (e.g. Jun, Fosl1, Tnik and Irak2), ware elevated. Finally, genes of additional microRNAs (e.g. Mir142 and Mir1957), as well as cell cycle (Gadd45b, S100a6) and survival molecules (e.g. Bcl10), had elevated expression (Table III).

Table III.

Genes of interest that were upregulated in eosinophils of the esophagus compared to the bone marrow in CC10Il13Tg/Pirb−/−mice but not in CC10Il13Tg/Pirb+/+mice

| Gene symbol | Fold change [Esophagus/Bone marrow] | |

|---|---|---|

| Surface molecules | Il5ra | 5.73 |

| Il12rb2 | 4.24 | |

| Notch2 | 3.69 | |

| Notch1 | 2.58 | |

| Bmpr2 | 2.52 | |

| Ifnar1 | 2.28 | |

| Cd300a | 2.61 | |

| Cell adhesion and migration molecules | Itgax | 6.04 |

| Itgb3 | 4.67 | |

| Itgal | 3.75 | |

| Vasp | 3.21 | |

| Ezr | 2.84 | |

| Acta1 | 2.75 | |

| Cd24a | 2.07 | |

| Enzymes | Capn2 | 5.66 |

| Mmp9 | 3.49 | |

| Adam19 | 2.73 | |

| Secreted factors | Il6 | 18.9 |

| Tnf | 5.72 | |

| Cxcl10 | 4.43 | |

| Tgfbi | 4.42 | |

| Ccl8 | 3.84 | |

| Areg | 2.18 | |

| Intracellular signaling molecules | Jun | 3.72 |

| Stat6 | 3.44 | |

| Nfkb2 | 2.90 | |

| Tnik | 2.71 | |

| Rela | 2.69 | |

| Fosl1 | 2.35 | |

| Jak2 | 2.25 | |

| Nfkbib | 2.24 | |

| Irak2 | 2.03 | |

| MicroRNA | Mir1957 | 9.22 |

| Mir142 | 8.29 | |

| Cell cycle molecules | Gadd45b | 5.63 |

| S100a6 | 2.09 | |

| Survival molecules | Bcl10 | 2.20 |

Discussion

IL-13 is a key Th2 cytokine that can directly promote many of the disease features associated with EoE, including eosinophil infiltration and esophageal remodeling. Most studies have focused on downstream effects of IL-13, and substantially less is known about the negative regulators of IL-13–induced esophageal pathology. In this study, we establish PIR-B as a novel inhibitory pathway that suppresses IL-13–induced eosinophil accumulation and subsequent activation in the esophagus. We demonstrated that: 1) the expression of Pirb is increased in the esophagus after exposure to IL-13; 2) eosinophils are the predominant contributors of the increased PIR-A/B expression in EoE; 3) PIR-B inhibits the development of IL-13–induced esophageal pathology, including eosinophilic accumulation, epithelial cell hyperplasia, collagen deposition, increased Acta2 levels and angiogenesis; 4) Eosinophil depletion experiments suggest that increased collagen deposition and angiogenesis in response to IL-13 in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice is likely due to loss of negative regulation in esophageal eosinophils; 5) and Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils display a distinct genetic signature associated with tissue repair. Collectively, our data establish PIR-B as an intrinsic negative regulator of eosinophil functions in IL-13–driven experimental EoE. This experimental finding may have implications for human EoE, which is characterized by IL-13–driven responses, as demonstrated by recent findings with anti–IL-13 treatment of patients with EoE (19).

We have established that following aeroallergen challenge, Pirb−/− mice display decreased lung eosinophilia and that PIRs critically regulate eosinophil maturation and expansion in homeostasis and in settings of aeroallergen-induced asthma (12). Subsequently allergen induced eosinophil infiltration into the lungs is decreased. In contrast, IL-13–induced eosinophil levels in the lung and esophageal compartment are elevated. This finding is likely due to the fact that the regulation of eosinophil functions by PIRs is confined to a specific anatomical location and specifically regulates IL-5 induced eosinophilpoiesis. For example, the role of PIRs in eosinophil expansion is restricted to the bone marrow compartment. However, once eosinophils “escape” the developmental regulation by PIRs and enter the blood, PIR-B is capable of suppressing eosinophil migration in response to eotaxins (14). This notion is reinforced by this study’s microarray data demonstrating a tissue-specific suppressive function for PIR-B (in terms of IL-13–regulated gene expression) in the esophagus but not the bone marrow. In addition, IL-13 induces eosinophilic inflammation via generating a strong chemotactic gradient for eosinophil recruitment independently of increasing the level of IL-5. We have recently demonstrated that PIR-B is a negative regulator or eosinophil chemotaxis in response to eotaxins (14). Interestingly, despite that finding that CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice express similar levels of eotaxins they still display markedly increased infilitration of eosinophils in the lungs and esophagus. Collectively, this suggests that Pirb−/− eosinophils hypermigrate in response to eotaxins as we previously shown (14).

Global microarray analyses revealed that IL-13–elicited esophageal eosinophils express multiple genes that are associated with fibrosis and tissue remodeling (e.g. Adam8, Ear11, Arg2, Mmp25, Ecm1, Retnla, Postn, Il1a, Il1b and Hif1a). Although these data are limited by the fact that we could not compare the genetic signature of IL-13–induced esophageal eosinophils with naïve esophageal eosinophils, it is important to note that the inflammatory conditions promoting tissue eosinophilia were associated with increased IL-13 (3, 20, 21) and that the normal esophagus is devoid of eosinophils. Thus, our results may reflect the genetic signature of eosinophils under disease conditions.

One of the notable findings of our study was that CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice display markedly increased tissue remodeling. This finding is of specific interest since structural cells such as epithelial cells, fibroblasts and endothelial cells do not express PIR-B. Thus, the increased tissue remodeling in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− may be due to the lack of PIR-B’s negative regulation of IL-13–mediated responses in a PIR-B+ cell type. Our findings suggest that PIR-B is a key negative regulator of eosinophil effector functions and may offer an explanation for the lack of eosinophil dependent pathology in IL-13 transgenic mice (3). In fact our finding suggest that expression of PIR-B in eosinophil may be sufficient to dampen their pathological activities in the esophagus. Indeed, the expression of PIR-B in the esophagus was predominantly associated with its expression in eosinophils, and CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice display increased eosinophilic infiltration to the esophagus, which was associated with increased tissue remodeling. In support of this notion, eosinophils express various pro-fibrogenic mediators including MMPs, TIMPs, VEGF, TGF-β, FGF and CCL18. Furthermore, clinical and experimental studies using eosinophil-deficient or hypereosinophilic mice tightly link eosinophils with tissue remodeling in numerous diseases including asthma and EoE. Thus, loss of PIR-B’s negative regulation in eosinophils may result in increased tissue remodeling. Indeed, using ERK phosphorylation as a surrogate marker for eosinophil activation, we clearly show that PIR-B negatively regulates ERK phosphorylation in response to the IL-13–induced esophageal microenvironment. Furthermore, microarray analyses on primary Pirb−/− esophageal eosinophils demonstrated a distinct genetic signature that was associated with a hyperactivated eosinophil phenotype. For example, genes of TGF-β signaling molecules that promote epithelial growth, fibrosis and tissue remodeling (i.e. Bmpr2, Bmp2, Tgfbi and smad3), as well as various factors that promote EMT (a recent pathway identified in EoE) and fibrosis (i.e. Notch1, Notch2, Mmp9, Adam19, Areg), had increased expression in Pirb−/− cells (2, 22–24). Integration of the ERK phosphorylation data and genetic signature analysis suggests that increased pathology in CC10-Il13Tg/Pirb−/− mice is not merely due to increased eosinophil numbers in the tissue but is also attributed to the fact that these eosinophils are hyperactivated.

Collectively, we demonstrate an inhibitory role for PIR-B in the regulation of esophageal eosinophil recruitment, activation and consequent esophageal pathology in response to IL-13 induction. Given the involvement of IL-13 in EoE and additional allergic diseases, the identification of an IL-13 dampening loop dependent upon PIR-B may have implications for human disease as PIR-B human orthologues are readily expressed by eosinophils (25). These data provide a new understanding into the signaling mechanisms that restrict eosinophil functions in EoE and may provide new therapeutic targets for combating EoE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank H. Kubagawa (Univ. of Alabama) for providing Pirb−/− mice, Dr. Jamie Lee (Mayo Clinic) for the anti-MBP reagent, and Shawna Hottinger for editorial assistance. This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree of Netali Morgenstern-Ben Baruch at the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Rothenberg ME. Biology and treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1238–1249. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuo L, Fulkerson PC, Finkelman FD, Mingler M, Fischetti CA, Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. IL-13 induces esophageal remodeling and gene expression by an eosinophil-independent, IL-13R alpha 2-inhibited pathway. J Immunol. 185:660–669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fulkerson PC, Fischetti CA, Hassman LM, Nikolaidis NM, Rothenberg ME. Persistent effects induced by IL-13 in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:337–346. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0474OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, Alpan O, Enav B, Hirano I, Nadeau K, Kaiser S, Peters T, Perez A, Jones I, Arm JP, Strieter RM, Sabo R, Gunawardena KA. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 135:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munitz A. Inhibitory receptors on myeloid cells: new targets for therapy? Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubagawa H, Chen CC, Ho LH, Shimada TS, Gartland L, Mashburn C, Uehara T, Ravetch JV, Cooper MD. Biochemical nature and cellular distribution of the paired immunoglobulin-like receptors, PIR-A and PIR-B. J Exp Med. 1999;189:309–318. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubagawa H, Burrows PD, Cooper MD. A novel pair of immunoglobulin-like receptors expressed by B cells and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ujike A, Takeda K, Nakamura A, Ebihara S, Akiyama K, Takai T. Impaired dendritic cell maturation and increased T(H)2 responses in PIR-B(−/−) mice. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:542–548. doi: 10.1038/ni801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheadon H, Paling NR, Welham MJ. Molecular interactions of SHP1 and SHP2 in IL-3-signalling. Cell Signal. 2002;14:219–229. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsuhashi Y, Nakamura A, Endo S, Takeda K, Yabe-Wada T, Nukiwa T, Takai T. Regulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cell responses by PIR-B. Blood. 120:3256–3259. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-419093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben Baruch-Morgenstern N, Shik D, Moshkovits I, Itan M, Karo-Atar D, Bouffi C, Fulkerson PC, Rashkovan D, Jung S, Rothenberg ME, Munitz A. Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor A is an intrinsic, self-limiting suppressor of IL-5-induced eosinophil development. Nat Immunol. 15:36–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma G, Pan PY, Eisenstein S, Divino CM, Lowell CA, Takai T, Chen SH. Paired immunoglobin-like receptor-B regulates the suppressive function and fate of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunity. 34:385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munitz A, McBride ML, Bernstein JS, Rothenberg ME. A dual activation and inhibition role for the paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B in eosinophils. Blood. 2008;111:5694–5703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-126748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuo L, Fulkerson PC, Finkelman FD, Mingler M, Fischetti CA, Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. IL-13 induces esophageal remodeling and gene expression by an eosinophil-independent, IL-13R alpha 2-inhibited pathway. J Immunol. 2010;185:660–669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karo-Atar D, Moshkovits I, Eickelberg O, Konigshoff M, Munitz A. Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor-B inhibits pulmonary fibrosis by suppressing profibrogenic properties of alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 48:456–464. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0329OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu VT, Frohlich A, Steinhauser G, Scheel T, Roch T, Fillatreau S, Lee JJ, Lohning M, Berek C. Eosinophils are required for the maintenance of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature immunology. 2011;12:151–159. doi: 10.1038/ni.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann N, McBride ML, Yamada Y, Hudson SA, Jones C, Cromie KD, Crocker PR, Rothenberg ME, Bochner BS. Siglec-F antibody administration to mice selectively reduces blood and tissue eosinophils. Allergy. 2008;63:1156–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, Alpan O, Enav B, Hirano I, Nadeau K, Kaiser S, Peters T, Perez A, Jones I, Arm JP, Strieter RM, Sabo R, Gunawardena KA. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;135:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:11–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.047. quiz 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, Abonia JP, Wu YY, Lu TX, Collins MH, Putnam PE, Wells SI, Rothenberg ME. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1292–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao J, Sheng H. Amphiregulin promotes intestinal epithelial regeneration: roles of intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts. Endocrinology. 151:3728–3737. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. Faseb J. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng E, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Tissue remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 303:G1175–1187. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00313.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tedla N, Bandeira-Melo C, Tassinari P, Sloane DE, Samplaski M, Cosman D, Borges L, Weller PF, Arm JP. Activation of human eosinophils through leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1174–1179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337567100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.