Summary

In the two decades since their initial discovery, DNA vaccines technologies have come a long way. Unfortunately, when applied to human subjects inadequate immunogenicity is still the biggest challenge for practical DNA vaccine use. Many different strategies have been tested in preclinical models to address this problem, including novel plasmid vectors and codon optimization to enhance antigen expression, new gene transfection systems or electroporation to increase delivery efficiency, protein or live virus vector boosting regimens to maximise immune stimulation, and formulation of DNA vaccines with traditional or molecular adjuvants. Better understanding of the mechanisms of action of DNA vaccines has also enabled better use of the intrinsic host response to DNA to improve vaccine immunogenicity. This review summarizes recent advances in DNA vaccine technologies and related intracellular events and how these might impact on future directions of DNA vaccine development.

Keywords: DNA vaccine, immunogenicity, molecular adjuvant, plasmid, vaccine delivery

Introduction

Unlike conventional protein-based vaccines, DNA vaccines are based on bacterial plasmids that encode vaccine antigens driven by efficient eukaryotic promoters [1]. Like protein vaccines, DNA vaccines can be delivered through a variety of different routes, including intramuscular, subcutaneous, mucosal, or transdermal delivery. However, unlike protein antigens, the DNA vaccine to be effective must gain entry to the cytoplasm of cells at the injection site in order to induce antigen expression in vivo, thereby enabling antigen presentation on major histocompatability molecules (MHC) and T-cell recognition. DNA vaccines have proved successful in a variety of animal models in preventing or treating infectious diseases, cancer, autoimmunity or allergy [2]. DNA vaccines have many advantages over traditional vaccines with vaccine design being straightforward, generally only requiring one-step cloning into plasmid vector thereby reducing cost and production time. Furthermore, the in vivo expression of an antigen gene driven by a eukaryotic promoter and endogenous post-translational modification results in native protein structures ensuring appropriate processing and immune presentation. From a safety aspect, cloning or synthesis of nucleic acids rather than having to purify proteins from pathogens avoids the need for use of pathogenic microorganisms in vaccine manufacture. Recombinant DNA technology allows almost any kind of molecular manipulation on plasmid DNA, including in vitro mutation, enabling rapid redesign of antigens for pathogens such as influenza that exhibit constant antigenic drift. Plasmid DNA has a good safety record in humans, with the most common side effects being mild inflammation at the injection site. Plasmid DNA is stable at room temperature, avoiding the need for a cold chain during transportation. DNA vaccines enable expressed antigens to be presented by both MHC class I and class II complexes, thereby enabling stimulation of both CD4 and CD8 T cells [3]. Already, several veterinary DNA vaccines have been approved for use, including in fish (infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus), dogs (melanoma), swine (growth hormone releasing hormone) and horses (West Nile virus) [4]. Human applications of the technology have lagged, largely due to the sub-optimal immunogenicity when compared to traditional vaccine approaches. To address these obstacles, a large number of different strategies to enhance DNA vaccine immunogenicity have been tested including vector design improvement, antigen codon optimization, use of traditional adjuvant and molecular adjuvants, electroporation, co-expression of molecular adjuvants and prime-boost strategies. In this review, we have specifically focused on promoter selection for DNA vaccine vectors, potential shortcomings of codon optimization, potential new insights from ‘omics’ studies and RNAi technologies, molecular adjuvants, targeting strategies and technologies for delivery of DNA vaccines. Although many of the described advances have so far only been tested in preclinical models, an increasing number have advanced to the stage of human clinical trial testing.

Mechanism of action of DNA vaccine

The first proof-of-concept DNA vaccine was tested in 1990 and involved injecting RNA or DNA vectors expressing chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, luciferase, and beta-galactosidase into mouse skeletal muscle [5]. The expression of reporter genes in vivo was readily detectable and lasted for two months. Subsequent gene gun studies showed that DNA-coated gold micro-projectiles when propelled into mouse skin were highly efficient in inducing antibody responses to the expressed antigen [6]. Finally it was shown that injecting plasmid expressing influenza nucleoprotein into the quadriceps of BALB/c mice could induce cytotoxic T lymphocytes with the immunized mice being protected from challenge with heterologous influenza A virus strains [7]. Similar studies in chickens also demonstrated protection against H7N7 influenza virus challenge after two doses of H7-HA DNA vaccine [8]. Although, these early studies confirmed the potential of using nucleic acids as vaccines, many practical questions still needed to be addressed. The first was the safety of plasmid DNA and the risk that it would integrate into chromosomes and induce activation of oncogenes or mutation of tumour suppressor genes or increase chromosome instability. Subsequent studies confirmed that DNA vaccines have an extremely low probability of human genome integration, at a level lower even than that of spontaneous mutations [9]. Another important question was how DNA vaccines, given their extremely low level of expression, are able to induce immune responses. Compared to the short half-life of injected protein antigens, plasmid DNA can provide tissue expression of antigens over much longer periods of time, thereby potentially priming the immune system better. In regard to antigen presentation, three possible mechanisms have been proposed: (1) the plasmid DNA is internalised and expressed by somatic cells (e.g. myocytes) and presented by their MHC class I complexes to CD8 T cells; (2) professional antigen presenting cells (APC), e.g. dendritic cells, attracted to the injection site are transfected by the plasmid DNA and the expressed antigens are presented to T cells through MHC class I and II complexes; (3) phagocytosis of plasmid-transfected somatic cells by professional APC resulting in cross-priming and presentation of antigen to both CD4 and CD8 T cells. Because muscle cells are not able to present antigen through MHC class II as needed to induce CD4 helper T cells, direct or indirect presentation by professional APC is the most likely route.

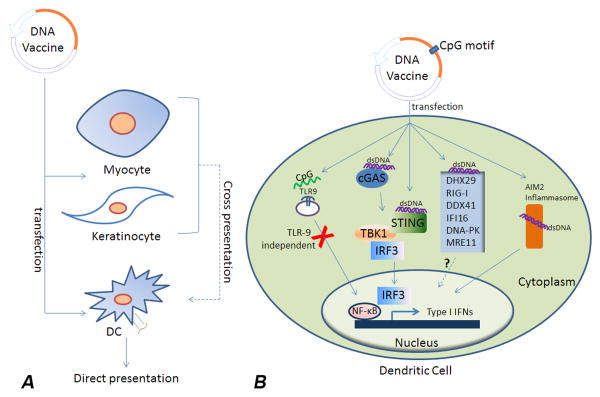

Intrinsic elements of plasmid DNA can also activate innate immune responses, thereby enhancing adaptive immune responses against the expressed antigens. The innate immune system uses pattern-recognition receptors (PRR) to sense invasion of pathogens and induce downstream production of type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines. In both mouse and human, toll-like receptor-9 (TLR9) is a cytosolic PRR that binds DNA sequences containing unmethylated cytosine-guanine (CpG) motifs leading to activation of MyD88-dependent signalling pathways [10]. CpG motifs are rare in mammalian genomes, in which they are generally methylated, whereas in bacteria unmethylated CpG motifs are common. Inclusion of built-in CpG motifs in DNA vaccine backbones acts to activate TLR9 after transfection. Ability of DNA vaccines to activate TLR9 has been suggested to be important in prime but not prime-boost contexts [11]. Although CpG motifs can play important roles in vaccine action, TLR9 knockout mice show that TLR9 is not essential for DNA vaccines to work [12,13], suggesting other cytosolic DNA sensors may also contribute to DNA vaccine immunogenicity. One such PRR is cyclic-GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS) which, after recognition of dsDNA, induces cGAMP to activate the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) [14-16]. Another DNA PRR is DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1), which also activates STING and induces type I interferon expression [17]. TBK1, downstream of cGAS and DAI, is important to enhancement of DNA vaccine action [18]. Another important cytosolic DNA sensor is AIM2, which induces inflammasome activation and inflammatory cytokine production [19,20]. A recent study showed that both the humoral and cellular antigen-specific adaptive responses to DNA vaccines were significantly reduced in AIM2-deficient mice [21]. The helicase proteins, DHX29 and RIG-I sense cytosolic nucleic acids and may contribute to DNA vaccine action [22]. Other potential DNA sensors include DDX41, IFI16, DNA-PK and MRE11 [23-28]. Hence, these PRR and downstream signalling pathways may provide valuable means to enhance DNA vaccine action (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of DNA vaccine sensing in transfected immune or non-immune cells.

(A) DNA vaccines transfect myocytes, keratinocytes or dendritic cells (DC). DCs are able to present antigens directly while myocytes or keratinocytes rely on cross-presentation pathways. (B) Molecular events are summarized for DC vaccines. TLR9 is not critical for DNA vaccine action, although it may still play a contributory role given the CpG motifs in most DNA vector backbones. Recent studies showed that STING/TBK1/IRF3 pathways and the AIM2 inflammasome are important to DNA vaccine action. Other innate immune receptors playing a role in DNA vaccine sensing include cyclic-GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS), AIM2, DHX29 and RIG-I. Additional potential DNA sensors are now under study, including DDX41, IFI16, DNA-PK and MRE11. Molecular adjuvants that represent ligands of the above sensors and signalling proteins are currently being tested for their ability to improve DNA vaccine immunogenicity.

Research models of DNA vaccines

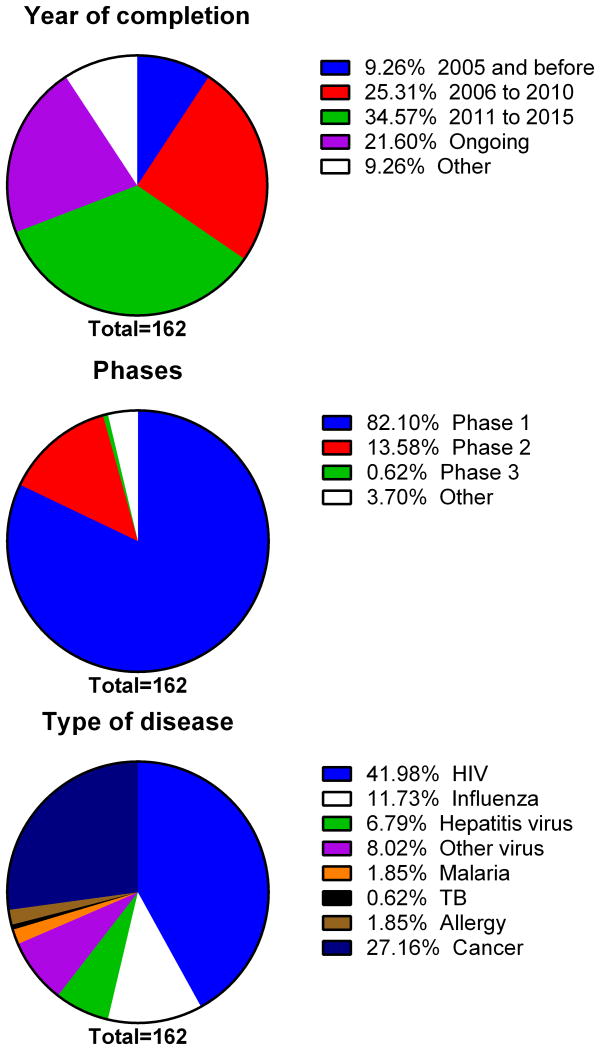

As in traditional vaccine research, small rodent laboratory animals are principally used for DNA vaccine research. For example, the query for “human” as the host from DNAVaxDB [29], a database collecting verified DNA vaccine study data returns only 6 records, while a query for “mouse” returns 168. Currently, this database has a total of 421 records of verified DNA vaccine studies including other animal models and some that are not clearly labelled. Although most of the studies cited in this review have been undertaken in mouse models rather than humans, they have been of critical importance in understanding the mechanisms by which DNA vaccines work, have helped in improving vector design and delivery methods and been useful for testing of adjuvants and for valuation of safety issues. While vaccine success in small animal models does not guarantee translation to humans, such studies remain an important part of the vaccine development pipeline. An increasing number of these advances from preclinical models have advanced into human clinical trials. As shown in Figure 2, we retrieved a total number of 162 records of DNA vaccines from a leading human clinical trial database (ClinicalTrials.gov) with more than half of the entries being from after 2011 with only 9% being from before 2005, indicating the relative infancy of human DNA vaccine research. Eighty-two percent of these registered DNA vaccine trials are listed as Phase 1, 13% as Phase 2 and only one trial is listed as Phase 3. Looking at the distribution of diseases DNA vaccines are currently being used to target, ∼ 60% are directed at viruses like HIV, influenza or hepatitis and with ∼ 27% targeting cancer. This is consistent with the need for new types of vaccines for viruses or diseases that are not well addressed using traditional vaccine approaches. Reassuringly, to date no major safety problems have emerged from human DNA vaccine trials.

Figure 2. Summary of human clinical trials involving DNA vaccines.

Number of clinical trials of DNA vaccines carried out in different time periods, clinical trial phases and the diseases being targeted are summarized for all 162 DNA vaccine trials registered in the ClinicalTrial.gov database.

DNA vaccine constructs design

Codon optimization

Codon usage of pathogens is often different to mammalian species, hence codon optimization is generally required to achieve efficient mammalian expression of pathogen proteins. Early studies in mouse models showed successful codon optimization results in enhanced CD8 T cell responses [30] and neutralizing antibody titres [31] and this has been supported by more recent studies [32-36]. Currently, different academic or commercial algorithms for codon optimization are available to assist DNA vaccine development [37,38]. However, codon optimization does not always positively correlate with DNA vaccine efficacy. For example, a malaria DNA vaccine study in mice showed that native nucleic acid sequence provided more robust T-cell responses and protection against P. yoelii sporozoite challenge [39]. Another murine study using codon-optimized plasmids that expressed Schistosoma mansoni Sm14 protein showed no increase in immunity or protection against S. mansoni challenge [40]. These discrepancies suggest that assumptions about codon optimization may not always hold true. Many studies have shown that rare-codons may not always be a speed-limiting step and frequently used codons do not guarantee increased protein production. Furthermore, synonymous codons could potentially change protein conformation and function as recently reviewed by Mauro et al [41]. Furthermore, the original pathogen sequences may provide better adjuvant effects through PRR interaction than codon optimized sequences. Therefore, it is best that both original and codon-optimized sequences be always compared in the early phase of developing a new DNA vaccine.

Promoter selection

DNA vaccine gene expression is normally driven by a polymerase II type promoter. The endogenous mammalian Pol II promoters are not as strong as virus-derived promoters, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) or SV40 promoters (e.g. pcDNA3.1, pVAX1, pVIVO2, pCI, pCMV and pSV2). Early studies showed the CMV immediate early enhancer/promoter had the strongest activity in most cell types and it was thus widely used for DNA vaccine design [42,43]. Studies using HIV-1 Env DNA vaccines have shown that stronger promoters induced higher protein expression and immune responses [44]. While some viral promoters can efficiently drive antigen expression, this has not always correlated with vaccine efficacy, an effect that may be explained by the viral promoters being sensitive to inhibition by inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα or IFN-γ. Non-viral promoters such as the MHC class II promoter have been shown in mice to overcome this issue [45]. Hence, while the CMV promoter, given its ability to drive a high level of protein expression, remains the first choice for most DNA vaccines, alternative promoters may result in better vaccine outcomes.

Optimization of plasmid vector backbone

Plasmid vectors used for DNA vaccine contain bacterial elements, such as replication signal and selection markers for propagation of E. coli. These elements can pose safety issues and result in poor antigen expression. For example, autoimmunity issues occurred when the Ampicillin selection marker in expression vector pcDNA3.1 was replaced with a Kanamycin selection marker [46]. Removing redundant vector sequences also makes it possible to clone larger DNA vaccine fragments. By using sucrose selection systems, traditional selection marker can be replaced. A sucrose selection construct was designed with incorporation of 72 base pair SV40 enhancer at the 5′ of CMV promoter to increase the extra-chromosomal transgene expression of the human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) R region at the 3′ of a CMV promoter to increase translation efficiency. Using this system, increased neutralizing antibody titers to HIV-1 gp120 DNA vaccination was achieved in rabbits [47].

To completely remove bacterial elements, a minicircle DNA (mcDNA) technology has been developed using site-specific recombination based on the ParA resolvase to generate mcDNA [48] or using inducible minicircle-assembly enzymes, PhiC31 integrase and I-SceI homing endonuclease [49]. mcDNA technology has been successfully used in gene therapy experiments in mouse models [50,51]. A recent study has shown that minicircle dna is superior to plasmid DNA in eliciting antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses [52]. Another study showed a modified novel Mini-Intronic Plasmid (MIP) system was robustly expressed in vivo and in vitro [53] and may thereby serve as a better vaccine backbone. Another study combined electroporation delivery along with minicircle DNA technology resulting in enhanced immunogenicity of a HIV-1 gag DNA vaccine in mice [54].

Traditional adjuvants for DNA vaccines

Vaccine adjuvants can be used to increase the immunogenicity of otherwise weakly immunogenic antigens. Vaccine adjuvants function through a series of mechanisms including activation of innate immune systems, formation of depot for efficient antigen delivery, induction of different chemokine expression, enhancing antigen uptake and presentation by professional APC and upregulation of co-stimulatory surface molecules [55]. Some such adjuvants have been shown to enhance the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines. Alum has been widely used as a vaccine adjuvant since 1926 [55], and is thought to work via induction of phagocytic cell death resulting in an immune danger signal [56]. Addition of alum adjuvant to a DNA vaccine encoding HBsAg increased antibody responses in mice, guinea pigs and nonhuman primates [57]. Similarly, formulation of a Toxoplasma gondii DNA vaccine with an alum adjuvant lead to increased survival in BALB/c mice [58]. As an alternative to alum, a polysaccharide adjuvant based on delta-inulin particles when used in a DNA prime-protein boost vaccine strategy, significantly increased humoral and cellular responses anti-Env-responses in mice [59]. Other approaches to DNA vaccines have used liposomes, which are spherical vesicles composed of lipid bilayer including phospholipids and cholesterol. Liposomes entrap or bind plasmid DNA and facilitate DNA entry into cells by penetrating the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane [60]. Although use of liposomes for intramuscular antigen delivery needs further improvement to overcome injection-site reactogenicity, they remain promising candidates for mucosal vaccination. A recent study in C57BL/6 mice showed that oral vaccination with cationic liposome-encapsulated pcDNA3.1-based influenza A virus M1 gene induced both humoral and cellular immune responses and protected the mice against respiratory infection [61]. Liposomes have also shown to be effective with intranasal DNA vaccination [62]. However, on the whole, traditional adjuvants have at best only modest effects on DNA vaccine immunogenicity, leading to attempts to develop more potent molecular adjuvant approaches.

Molecular adjuvants for DNA vaccines

Many vaccine plasmid-encoded immune-stimulatory molecules including various cytokine genes or PRR ligands have been tested as ‘genetic adjuvants’. These genetic or molecular adjuvants take advantage of recombinant DNA technology, allowing them to be encoded in the same plasmid as the vaccine or a co-administered plasmid.

Ligands of pattern recognition receptors

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of membrane-bound PRR that play key roles in the innate immune system. So far, 13 related human TLR genes (TLR1–TLR13) have been identified [63]. TLR3 and TLR9 recognize dsRNA and ssDNA, respectively, and their ligands have been shown to act as molecular adjuvants. Poly (I:C) is a classical TLR3 ligand. Poly (I:C) adjuvant enhanced inducing CTL immunity and decreased tumour burden in mice given a DNA cancer vaccine [64]. Poly (I:C) similarly enhanced responses to a HPV-16 E7 DNA vaccine [65]. A combined CpG/Poly (I:C) adjuvant enhanced the immunogenicity in mice of a DNA vaccine against eastern equine encephalitis virus [62]. Similarly, the TLR9 ligand, CpG, has been successfully used to enhance immunogenicity of DNA vaccines [62,66-68]. RIG-I-like receptors are important intracellular proteins that sense double stranded RNA. The RIG-I ligand, eRNA41H, enhanced the humoral immune response to an influenza DNA vaccine [69]. Similarly, a Sendai virus-derived 546-nucleotide ligand of RIG-I enhanced immunogenicity of influenza DNA vaccine [70]. TLRs, RIG-I-like receptor (RLRs), inflammasome and STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensor ligands can all initiate Th2 cell differentiation [71]. Ligands of the cytosolic DNA sensor DAI have also been shown to be efficient molecular adjuvant for DNA cancer vaccines [72].

Plasmid-encoded cytokines

Cytokines are naturally produced small proteins critical for immune cell signalling. Cytokine-encoding plasmids can be prepared along with the antigen-expressing plasmid and, local expression of cytokines at the injection site avoids the potential toxicity of systemically administered cytokines. Interleukin (IL)-2 induces the proliferation of T and NK cells, and has been extensively studied as a genetic adjuvant [73-82]. A fusion construct of Mycoplasma pneumoniae p1 gene carboxy terminal region with IL-2 resulted in enhanced vaccine responses in mice [83]. A therapeutic vaccine for chronic myeloid leukemia expressing BCR/ABL-pIRES together with IL-2 also showed enhanced immune responses [84].

IL-12 is another proinflammatory cytokine secreted by DCs and monocytes. IL12 expression plasmids have been shown to enhance Th1 immune responses [85]. A bicistronic plasmid expressing Yersinia pestis epitopes and IL-12 increased mucosal IgA and serum IgG and protected mice from challenge [86]. IL-12 expression plasmids have also been used for a clinical trial of a weakly immunogenic hepatitis B DNA vaccine [87]. A recent study showed that IL12 genetic adjuvant enhanced hepatitis C DNA vaccine immunogenicity through stimulation of IL-4 and IFN-γ production [88]. A study of a Toxoplasma gondii DNA vaccine showed that the immune responses and survival rate were increased by inclusion of an IL-12 genetic adjuvant compared [89]. An IL-12-adjuvanted HIV/SIV DNA vaccine was also successful in a DNA prime /protein boost study [90]. Evaluation of the PENNVAX-B HIV1 DNA vaccine that is a mixture of 3 expression plasmids encoding HIV-1 Clade B Env, Gag, and Pol, adjuvanted by the IL-12 DNA plasmid showed the vaccine to be safe. Administration of PENNVAX-B with IL-12 plus electroporation had a significant dose-sparing effect and provided superior CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell immunogenicity [91].

GM-CSF is known to recruit APC to immunization site and promote DC maturation. It has been successfully used in DNA vaccines, including with a Pseudorabies virus gB-encoding, SIV encoding and DENV serotype 2 prM/E encoding, vaccines [92-95]. However, a recent study showed that co-administration of GM-CSF plasmid can have deleterious effects, causing suppression to a DNA vaccine against dengue virus type 1 and type 2 and failing to improve the response induced by HCV vaccine [96]. Furthermore, excessive GM-CSF can expand myeloid suppressor cells and suppress adaptive immune responses. Notably, in preclinical macaque studies GM-CSF expressed in recombinant SIV and MAV vaccines did not enhance protection [97]. Therefore, when used as a molecular adjuvant fine-tuning of GM-CSF expression levels must also be considered.

IL-15 is a cytokine that induces NK and T cell proliferation [98]. A synergistic effect of IL-15 and IL-21 was seen in a DNA vaccine against Toxoplasma gondii infection [99,100]. Sequential administration of IL-6, IL-7 and IL-15 genes enhanced CD4+ T cell memory to a DNA vaccine against foot and mouth disease [101]. Hence combinations of multiple cytokines in a DNA vaccine formulation or sequential vaccination with cytokines may enhance vaccine efficacy.

Easy cloning of cytokine genes makes them promising candidates as DNA vaccine adjuvants. The moderate but more durable expression at the injection site of plasmid-expressed cytokines helps overcome the problem of the short half-life of many cytokines while minimizing the risk of a systemic cytokine “storm” by restricting cytokine expression to the injection site. Although human data on use of cytokine-encoding plasmids as vaccine adjuvants is limited, this appears a promising direction for fine-tuning immune responses to DNA vaccines.

Plasmid-encoded signalling molecules

In the past ten years, understanding of immune signalling pathways has greatly progressed, making it possible to test such signalling molecules as vaccine adjuvants. Signalling molecules, TRIF and HMGB1, have been successfully tested as genetic adjuvants for DNA vaccines [102]. Similarly, co-transfection with HSP70 enhanced better CTL responses to DNA vaccines [103]. PD-1 based plasmids were shown to enhance DNA-vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell responses against HIV [104]. MDA5, a RIG-I like dsRNA receptor, enhanced DNA vaccination against H5N1 influenza virus infection in chickens [105]. Recent studies showed that a plasmid expressing interferon regulatory transcription factor (IRF), enhanced CTL and IFN-γ responses against an HIV-1 Tat vaccine [106], whereas no effects were observed with IRF3 or IRF7 plasmids [106]. NF-κB is a master innate immune regulator. A recent study showed that co-administration of a plasmid expressing NF-κB subunit p65/RelA enhanced DNA vaccine immunogenicity [107]. A T-cell transcription factor, Tbet was effective in driving a Th1 response against an Ag85B DNA-based tuberculosis vaccine [108,109]. DNA, itself, through binding to cellular receptors can activate innate immune pathways. A recent study found that a short noncoding DNA fragment of ∼300bp improved electroporation-mediated gene transfer in vivo [110], and the immune potency of a HBV vaccine [111].

shRNA or siRNA as molecular adjuvants

RNA interference (RNAi) is a post-transcriptional gene silencing process triggered by double-stranded short hairpin RNA (shRNA) structures. Since its discovery, RNAi has mainly been used as a research tool for loss of function studies of target genes [112]. RNAi can be used to down-regulate genes that suppress DNA vaccine action. For example, use of shRNA to knock down caspase 12, a cell death mediator that is upregulated after DNA vaccination, increased plasmid gene expression and T-cell and antibody responses [113]. Similarly, depletion by RNAi of Foxo3, a critical suppressive regulator of T cell proliferation, increased the efficacy of a HER-2/neu cancer vaccine [114]. Knockdown of the IL10 receptor was also shown to enhance vaccine potency [115]. Furthermore, blockade of the PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) by RNAi augmented DC-mediated T cell responses and antiviral immunity in HBV transgenic mice [116]. A recent cancer vaccine study that combined IL-10 siRNA and CpG showed increased protective immunity against B cell lymphoma [117]. Another cancer therapeutic vaccine showed that GM-CSF combined with shRNA knockdown of furin augmented vaccine efficacy [118]. Knockdown of APOBEC expression by RNAi also enhanced DNA vaccine immunogenicity [119]. Thus use of RNAi against target genes that limit plasmid expression might be a powerful new strategy for DNA vaccine enhancement, especially for tumour vaccines, but with the safety of this approach still needing to be fully evaluated in animal studies.

DNA vaccine targeting technologies

DNA vaccines mainly transfect muscle cells resulting in poor antigen presentation due to lack of co-stimulation. Instead gene expression can be targeted to professional APC to enhance vaccine action. One strategy is direct transfection of DC. A conventional approach is to use ex vivo-engineered DC vaccines, where enriched DC from blood are transfected with DNA before being given back to the patient. One recent mouse study showed that DC transfected with Spermine-dextran/CCR7 plasmid/gp100 plasmid migrated to lymph nodes when re-administered to mice [120]. Given the high cost of DC vaccines this approach is only likely to be used for therapeutic cancer vaccines [121]. More recent studies improved the efficacy of plasmid DNA by adding targeting protein, polymer or peptides. Liu et al. translated the “albumin hitchhiking” approach to DNA vaccines by using the lipophilic albumin-binding tail to target the cargo to DC [122]. Skin delivery of DNA loaded into polymer forming nanoparticles has been used to target Langerhans cells [123]. The barrier of direct targeting DNA to DC was overcome by incubating DNA vaccines with a small peptide derived from the rabies virus glycoprotein fused to protamine residues [124]. In addition to direct targeting of DNA to DC, another strategy is to co-express DC-targeting molecules in the DNA vaccine construct. Many such targeting approaches have been successful in mouse models, utilising a wide range of targeting molecules including FIRE (F4/80-like receptor), CIRE (C-type lectin receptor), Cle9A, Flt3, DEC205, xrc1 or synthetic MHC class II-targeting peptides [125-132].

Subcellular targeting is another strategy for enhancing plasmid-encoded antigen processing and/or presentation. Using E1A targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum or LAMP targeting to lysosome can greatly enhance DNA vaccine efficacy [133,134]. Targeting of the autophagy pathway enhanced the efficacy of tuberculosis DNA vaccines [135-137]. Similarly, a short polypeptide from herpes simplex virus that induces antigen aggregation and autophagosomal degradation enhanced T-cell-responses when co-expressed with chicken ovalbumin [138]. The plasmid pATRex expressing the aggregation domain of TEM8 induces intracellular protein aggregation, autophagy and caspase activation and this translated to an increased IgG1 response by a DNA vaccine encoding Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 4/5 [139]. Fusion of the PADRE MHC class II epitope to a cancer DNA vaccine was also able to induce stronger antigen-specific responses [140].

Targeting DNA vaccine to specific cells or subcellular compartments can greatly increase antigen processing and presentation and promote the desired immune responses, while minimizing systemic toxicity. It is thereby a very promising area of molecular adjuvant development. Among different ways of targeting DC, skin targeting methods (intradermal injection or micro-needles) may be superior to traditional intramuscular or subcutaneous injection routes [141] and this will be further discussed in the section on vaccine delivery devices.

High-throughput screening technologies

Developments in next-generation sequencing, microarrays, and high throughput proteomics approaches now provide opportunity to identify additional potential molecular adjuvants for DNA vaccines. One recent proteomics study screened proteins for interaction with plasmid DNA and found that human serum amyloid P (SAP) inhibited plasmid transfection and enhanced clearance. SAP may contribute to the low efficacy of DNA vaccines in humans, with its suppressive effects being much weaker in other species [142]. Therefore, it might be possible to include shRNA against SAP as a molecular adjuvant for human DNA vaccines. Systems biology approaches have also been used to analyze the molecular signatures that correlate with a positive immunization response. For example, CaMKIV kinase expression levels at day 3 were negatively correlated with subsequent influenza antibody titers [143]. This provides an example of the application of systems biology to identify biomarkers that predict vaccine effectiveness [144-147] with identified molecules serving as potential new candidate molecular adjuvants.

Prime-boost strategies

The immunogenicity of DNA vaccines is limited in humans. Prime-boost approaches like DNA prime/protein boost, DNA prime/viral vector boost (e.g. using adenovirus) and even protein prime/DNA boost provide opportunities to develop more effective human DNA vaccine regimens. Previous studies have used DNA/protein or DNA/Ad-vector approaches for HIV vaccination [148-152]. A recent study using a heterologous prime/boost approach showed enhanced immunogenicity of therapeutic vaccines for hepatitis C virus, with higher protection in a recombinant Listeria-NS3 1a –based surrogate challenge model [153]. Another study showed that a DNA prime/adenovirus boost malaria vaccine encoding P. falciparum CSP and AMA1 induced cell-mediated immunity and sterile protection [154]. Similar studies also showed greatly enhanced immunogenicity with a peptide prime/DNA boost or BCG prime/DNA boost, [155,156]. The interval between prime and boost was also important for best vaccine efficacy [157,158]. The underlying mechanisms of the effectiveness of prime-boost strategy still remain poorly understood, but we hypothesize that the lower antigen expression from DNA vaccines may preferentially prime T-helper cell responses with the humoral response being subsequently boosted by the protein or viral-vector boost.

Vaccine delivery

To overcome the main issue of low DNA vaccine immunogenicity, efficient delivery to plasmid to preferred tissues or cells is a critical research area. Just as in the case of conventional protein vaccines, DNA vaccines can be administrated by many different methods, including conventional syringe injection, gene gun, electroporation (EP) [159,160], nanoparticles [161], microneedles [162] and liposomes [163]. Based on animal studies, EP combined with a prime-boost strategy may give the highest immunogenicity. However, even though clinical trials of EP have been successfully undertaken [164,165] and shown dose-sparing effects [166], EP is not guaranteed to increase vaccine immunogenicity [165], and may not be practicable for many human vaccines. Hence simpler but more efficient methods are still needed for DNA vaccine delivery. Potential candidates include needle-free skin delivery or pulmonary delivery. Needle-free skin gene delivery systems use high-pressure fine streams to target different skin depths. The delivered DNA is then able to transfect Langerhans cells in the skin. Commercial devices such as Biojector or Pharmajet have been shown to be able to deliver DNA vaccines in animal models and human trials. A recent study using a rabbit model showed that an influenza DNA vaccine delivered by needle-free IDAL vaccinator elicited a similar antibody response to intradermal electroporation [167]. Another clinical trial used Biojector to deliver an HIV-1 DNA vaccine (VRC-HIVDNA016-00-VP) with good tolerance and priming for CD8+ T cell IFN-γ production and antibody responses after rAd5 boosting [168]. Considering its safety, low-cost and ease of use and the ability to deliver dry-coated plasmids [169,170], needle-free injection devices show much promise for DNA vaccine delivery.

Intranasal or intrapulmonary delivery of DNA vaccines are additional alternatives although the number of human studies of such administration routes is very limited. In theory, pulmonary vaccination should expose the delivered DNA and expressed antigens to a large surface of epithelial and immune cells while avoiding the need for needle injection [171-174]. A recent study showed that cation-complexed HIV-1 plasmid DNA vaccines applied topically to the murine pulmonary mucosa induced both mucosal and systemic immune responses models [175]. Furthermore, when complexed with PEI a pulmonary DNA vaccine induced significant influenza protection [175]. Another study showed that pulmonary DNA immunization mediated protective anti-viral immunity through enhancement of airway CD8+ T cell responses [176]. The biggest challenge for pulmonary delivery is the need for specialized delivery methods. Conventional jet or ultrasonic nebulizers fail to deliver large intact biomolecules like plasmid DNA to the lung because of the high shear and cavitational stresses present during nebulization. However, recent progress in the area of delivery methods may change this, with surface acoustic wave nebulization being shown to efficiently deliver an aerosolized plasmid DNA vaccine in rats or sheep with induction of systemic and mucosal antibody responses [177].

Expert commentary and 5-year view

Progress in overcoming the low immunogenicity problem of DNA vaccines has been steadily made. Recent advances are summarized in Table 1. Along with better understanding of immune pathways and vaccine action, a large array of immune receptors, signalling molecules, cytokines and transcription factors are in the process of being tested as DNA vaccine adjuvants. It is likely that at least some of these will turn out to be potent adjuvants, although each will need to be carefully assessed for human safety and tolerability. The ability to present native conformational immunogens and be able to prime both humoral and cellular immune responses are the hallmarks of DNA vaccines. Considering the suitability and convenience of needle-free injection and pulmonary delivery, these represent an exciting area for human DNA vaccine development over coming years.

Table 1. Summary of recent key advances in DNA vaccine design.

| Development of DNA vaccine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge or technologies from before | Recent updates and comments | ||

| Mechanism of action of DNA vaccine | Critical dsDNA sensor and signalling pathways | TLR9 as sensor of CpG DNA bacterial origin [10]. | TLR9 is now known not to be critical for DNA vaccine action [12, 13]. |

| MAVS, TBK1, IRF3 and STING are key signalling proteins. | TBK1-STING signalling shown important for DNA vaccine action and STING shown to be a dsDNA sensor [18]. | ||

| DAI, AIM2 and RNA pol III are DNA sensors [19-21]. | DAI is now known not to be critical for DNA vaccine action [17]. More dsDNA sensors were found, including LRRFIP1, DHX9, DHX36, IFI16, Ku70, DDX41, DNA-PK, MRE11, cGAS and Rad50 [22-28]. cGAS could be another key sensor of DNA vaccines [14-16]. | ||

| DNA vaccine design | Antigen sequence design | Based on experience or back-translation of protein antigens. | High-throughput ‘omics’ technologies will allow rapid identification and design of optimal antigen sequences [143-147]. |

| Codon optimization | Codon optimization thought important for all DNA vaccines [30-36]. | Evidence showed codon optimization may not always have positive effect on vaccine immunogenicity [39-41]. It is recommended to always include the original gene version for comparison with any new codon-optimized antigen sequence. | |

| Promoter selection | CMV promoter considered optimal [42, 43]. DNAVaxDB records show the CMV promoter was used in 109 out of 181 total DNA vaccine trials. The dominant vectors were pcDNA3 or pVAX based [29]. | CMV promoter is still the first choice. But non-viral promoters, e.g. MHC-II promoter, have also been shown to be good alternatives if CMV promoter not suitable [45]. | |

| Removal of bacterial element | Hard to achieve using conventional vectors such as pcDNA or pVAX. | Minicircle DNA (mcDNA) [49-52] and Mini-Intronic Plasmid (MIP) systems [53, 54] are promising for future development. | |

| Molecular adjuvants | TLR ligands, e.g. CpG ODN or poly(I:C) as DNA vaccine adjuvants [64, 65]. | Greater range of molecular adjuvants. RIG-I ligand, e.g. eRNA41H, shown to enhance DNA vaccine action [69]. STING ligand can initiate Th2 cell differentiation in mouse model [71]. Ligands to dsDNA sensor, DA1, shown to be efficient adjuvants for cancer DNA vaccines [72]. | |

| Plasmid-encoded cytokines or chemokine shown to have adjuvant effects for DNA vaccines in animal studies [102]. | Effects of genetic cytokine adjuvants have been supported by more recent studies. But studies also showed that in some cases GM-CSF is negative [96, 97]. Cytokine expression needs to be tuned to avoid “cytokine storm”. Safety aspects need to be carefully considered for such adjuvants. | ||

| Plasmid-encoded signalling molecules such as TRIF or HMGB1 shown to act as DNA vaccine adjuvants [102]. | MDA5 (a RIG-I like dsRNA receptor) [105], NF-kB [107] and Tbet [108, 109] shown to be effective adjuvants. A large range of signaling molecules are now available as candidate adjuvants for DNA vaccines. | ||

| Immune regulatory genes impeding DNA vaccine action not considered. | shRNA or siRNA targeting certain regulatory genes, e.g. caspase 12 [113], Foxo3 [114], PD-L1 [116] and IL-10 [117] shown to have adjuvant effects. RNAi against APOBEC enhanced DNA vaccine immunogenicity [119]. | ||

| Targeting technologies | Direct DC targeting | DC vaccines loaded with antigen, ex vivo. | DCs can now be targeted directly in vivo. Lipophilic albumin-binding tail approach directly targets DC in vivo [122]. Polymer forming nanoparticles shown to target Langerhans cells after skin delivery [123]. |

| Co-expression of DC targeting molecules | DC targeting ex vivo. | Broader range of molecules targeting DC in vivo identified, e.g. FIRE, CIRE, Cle9a, Flt3, DEC205, xrc1 or synthetic MHC-II [125-132]. Now being used in combination with skin-delivery methods [141]. | |

| Prime-boost strategy | DNA vaccines largely used by themselves but with poor immunogenicity despite repeated doses. | Increased awareness of the importance of prime boost strategies to boost DNA vaccine immunogenicity [153-158]. | |

| DNA vaccine delivery | Syringe injection, gene gun [159, 160], nanoparticle [161], micro-needle [162] and liposomes [163] extensively studied. Limitations in regard of ease of use and efficiency of delivery. | Although new methods are being tested, conventional intramuscular injection still dominates DNA vaccine delivery. | |

| Electroporation shown to be efficient in animal models. | Electroporation (EP) is now being combined with intradermal vaccine delivery. Tolerability and cost remains an issue and EP is simply not practical for most human vaccine applications. | ||

Key issues.

DNA vaccines have the benefits of being able to express antigens in their native conformation inside cells and thereby induce CD8+ T cell responses.

Currently more than 150 human DNA vaccine trials are ongoing or completed.

Animal and human trial data has showed good tolerance and safety of DNA vaccines.

Codon optimization and strong viral promoters do not always enhance DNA vaccine immunogenicity.

Minicircle DNA or Mini-Intronic Plasmid systems are promising for bacterial element-free DNA vaccine production.

Molecular adjuvants including plasmid-encoded cytokines and signalling molecules and RNA knockdown strategy can be used to enhance DNA vaccine immunogenicity.

Needle-free skin delivery or pulmonary delivery methods may be promising directions for future use.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: The authors of this work were supported by funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No HHSN272201400053C and HHSN272200800039C. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests disclosure: The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Reference annotations

* Of interest

** Of considerable interest

- 1.Rajcani J, Mosko T, Rezuchova I. Current developments in viral DNA vaccines: shall they solve the unsolved? Rev Med Virol. 2005;15(5):303–325. doi: 10.1002/rmv.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdulhaqq SA, Weiner DB. DNA vaccines: developing new strategies to enhance immune responses. Immunol Res. 2008;42(1-3):219–232. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu MA. DNA vaccines: an historical perspective and view to the future. Immunological reviews. 2011;239(1):62–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kutzler MA, Weiner DB. DNA vaccines: ready for prime time? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(10):776–788. doi: 10.1038/nrg2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff JA, Malone RW, Williams P, et al. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science. 1990;247(4949 Pt 1):1465–1468. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang DC, DeVit M, Johnston SA. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature. 1992;356(6365):152–154. doi: 10.1038/356152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Ulmer JB, Donnelly JJ, Parker SE, et al. Heterologous protection against influenza by injection of DNA encoding a viral protein. Science. 1993;259(5102):1745–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.8456302. Early pioneer study of DNA vaccine showed original ideas and immunogenicity of DNA vaccines in animal models. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson HL, Hunt LA, Webster RG. Protection against a lethal influenza virus challenge by immunization with a haemagglutinin-expressing plasmid DNA. Vaccine. 1993;11(9):957–960. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90385-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faurez F, Dory D, Le Moigne V, Gravier R, Jestin A. Biosafety of DNA vaccines: New generation of DNA vectors and current knowledge on the fate of plasmids after injection. Vaccine. 2010;28(23):3888–3895. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408(6813):740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rottembourg D, Filippi CM, Bresson D, et al. Essential role for TLR9 in prime but not prime-boost plasmid DNA vaccination to activate dendritic cells and protect from lethal viral infection. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):7100–7107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Babiuk S, Mookherjee N, Pontarollo R, et al. TLR9-/- and TLR9+/+ mice display similar immune responses to a DNA vaccine. Immunology. 2004;113(1):114–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01938.x. This study showed that TLR9 is not necessary for DNA vaccine activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tudor D, Dubuquoy C, Gaboriau V, Lefevre F, Charley B, Riffault S. TLR9 pathway is involved in adjuvant effects of plasmid DNA-based vaccines. Vaccine. 2005;23(10):1258–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao P, Ascano M, Wu Y, et al. Cyclic [G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] is the metazoan second messenger produced by DNA-activated cyclic GMP-AMP synthase. Cell. 2013;153(5):1094–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339(6121):786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. cGAS was found to be another critical dsDNA sensor inaddition to STING and has critical roles in enhancement of immune responses for DNA vaccines. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Yeruva L, Marinov A, et al. The DNA sensor, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase, is essential for induction of IFN-beta during Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Immunol. 2014;193(5):2394–2404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takaoka A, Wang Z, Choi MK, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448(7152):501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Ishii KJ, Kawagoe T, Koyama S, et al. TANK-binding kinase-1 delineates innate and adaptive immune responses to DNA vaccines. Nature. 2008;451(7179):725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature06537. This study confirmed that TBK1 is critical for DNA vaccine activities. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Juliana C, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nature immunology. 2010;11(5):385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroder K, Muruve DA, Tschopp J. Innate immunity: cytoplasmic DNA sensing by the AIM2 inflammasome. Current biology : CB. 2009;19(6):R262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suschak JJ, Wang S, Fitzgerald KA, Lu S. Identification of Aim2 as a sensor for DNA vaccines. J Immunol. 2015;194(2):630–636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugimoto N, Mitoma H, Kim T, Hanabuchi S, Liu YJ. Helicase proteins DHX29 and RIG-I cosense cytosolic nucleic acids in the human airway system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(21):7747–7752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400139111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson BJ, Mansur DS, Peters NE, Ren H, Smith GL. DNA-PK is a DNA sensor for IRF-3-dependent innate immunity. eLife. 2012;1:e00047. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobsen MR, Paludan SR. IFI16: At the interphase between innate DNA sensing and genome regulation. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2014;25(6):649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo T, Kobayashi J, Saitoh T, et al. DNA damage sensor MRE11 recognizes cytosolic double-stranded DNA and induces type I interferon by regulating STING trafficking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(8):2969–2974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222694110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parvatiyar K, Zhang Z, Teles RM, et al. The helicase DDX41 recognizes the bacterial secondary messengers cyclic di-GMP and cyclic di-AMP to activate a type I interferon immune response. Nature immunology. 2012;13(12):1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/ni.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unterholzner L, Keating SE, Baran M, et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nature immunology. 2010;11(11):997–1004. doi: 10.1038/ni.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z, Yuan B, Bao M, Lu N, Kim T, Liu YJ. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nature immunology. 2011;12(10):959–965. doi: 10.1038/ni.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racz R, Li X, Patel M, Xiang Z, He Y. DNAVaxDB: the first web-based DNA vaccine database and its data analysis. BMC bioinformatics. 2014;15(Suppl 4):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-S4-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchijima M, Yoshida A, Nagata T, Koide Y. Optimization of codon usage of plasmid DNA vaccine is required for the effective MHC class I-restricted T cell responses against an intracellular bacterium. J Immunol. 1998;161(10):5594–5599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trollet C, Pereira Y, Burgain A, et al. Generation of high-titer neutralizing antibodies against botulinum toxins A, B, and E by DNA electrotransfer. Infection and immunity. 2009;77(5):2221–2229. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01269-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li K, Gao L, Gao H, et al. Codon optimization and woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhance the immune responses of DNA vaccines against infectious bursal disease virus in chickens. Virus research. 2013;175(2):120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seo JY, Chung HJ, Kim TJ. Codon-optimized expression of fish iridovirus capsid protein in yeast and its application as an oral vaccine candidate. Journal of fish diseases. 2013;36(9):763–768. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spatz SJ, Volkening JD, Mullis R, Li F, Mercado J, Zsak L. Expression of chicken parvovirus VP2 in chicken embryo fibroblasts requires codon optimization for production of naked DNA and vectored meleagrid herpesvirus type 1 vaccines. Virus genes. 2013;47(2):259–267. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0944-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams JA. Improving DNA vaccine performance through vector design. Current gene therapy. 2014;14(3):170–189. doi: 10.2174/156652321403140819122538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Y, Lu F, Dai Y, et al. Synergistic enhancement of immunogenicity and protection in mice against Schistosoma japonicum with codon optimization and electroporation delivery of SjTPI DNA vaccines. Vaccine. 2010;28(32):5347–5355. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Deng R, Wang J, Wang X. COStar: a D-star Lite-based dynamic search algorithm for codon optimization. Journal of theoretical biology. 2014;344:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobs TM, Yumerefendi H, Kuhlman B, Leaver-Fay A. SwiftLib: rapid degenerate-codon-library optimization through dynamic programming. Nucleic acids research. 2014 doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dobano C, Sedegah M, Rogers WO, et al. Plasmodium: mammalian codon optimization of malaria plasmid DNA vaccines enhances antibody responses but not T cell responses nor protective immunity. Exp Parasitol. 2009;122(2):112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varaldo PB, Miyaji EN, Vilar MM, et al. Mycobacterial codon optimization of the gene encoding the Sm14 antigen of Schistosoma mansoni in recombinant Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guerin enhances protein expression but not protection against cercarial challenge in mice. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology. 2006;48(1):132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41*.Mauro VP, Chappell SA. A critical analysis of codon optimization in human therapeutics. Trends in molecular medicine. 2014;20(11):604–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.09.003. This review comments on good and bad sides of codon optimization in human DNA therapeutics, suggesting more considering is required for DNA vaccine design. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng L, Ziegelhoffer PR, Yang NS. In vivo promoter activity and transgene expression in mammalian somatic tissues evaluated by using particle bombardment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(10):4455–4459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manthorpe M, Cornefert-Jensen F, Hartikka J, et al. Gene therapy by intramuscular injection of plasmid DNA: studies on firefly luciferase gene expression in mice. Human gene therapy. 1993;4(4):419–431. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.4-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S, Farfan-Arribas DJ, Shen S, et al. Relative contributions of codon usage, promoter efficiency and leader sequence to the antigen expression and immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24(21):4531–4540. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanniasinkam T, Reddy ST, Ertl HC. DNA immunization using a non-viral promoter. Virology. 2006;344(2):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Q, Wang F, Zhang Y, Yang F, Wang Y, Sun S. Down-regulation of Prdx6 contributes to DNA vaccine induced vitiligo in mice. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7(3):809–816. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00181c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luke JM, Vincent JM, Du SX, et al. Improved antibiotic-free plasmid vector design by incorporation of transient expression enhancers. Gene Ther. 2011;18(4):334–343. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jechlinger W, Azimpour Tabrizi C, Lubitz W, Mayrhofer P. Minicircle DNA immobilized in bacterial ghosts: in vivo production of safe non-viral DNA delivery vehicles. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;8(4):222–231. doi: 10.1159/000086703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kay MA, He CY, Chen ZY. A robust system for production of minicircle DNA vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(12):1287–1289. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osborn MJ, McElmurry RT, Lees CJ, et al. Minicircle DNA-based gene therapy coupled with immune modulation permits long-term expression of alpha-L-iduronidase in mice with mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Mol Ther. 2011;19(3):450–460. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zuo Y, Wu J, Xu Z, et al. Minicircle-oriP-IFNgamma: A Novel Targeted Gene Therapeutic System for EBV Positive Human Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dietz WM, Skinner NE, Hamilton SE, et al. Minicircle DNA is superior to plasmid DNA in eliciting antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. Mol Ther. 2013;21(8):1526–1535. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu J, Zhang F, Kay MA. A mini-intronic plasmid (MIP): a novel robust transgene expression vector in vivo and in vitro. Mol Ther. 2013;21(5):954–963. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Q, Jiang W, Chen Y, et al. In vivo electroporation of minicircle DNA as a novel method of vaccine delivery to enhance HIV-1-specific immune responses. Journal of virology. 2014;88(4):1924–1934. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02757-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrovsky N, Aguilar JC. Vaccine adjuvants: current state and future trends. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82(5):488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marichal T, Ohata K, Bedoret D, et al. DNA released from dying host cells mediates aluminum adjuvant activity. Nature medicine. 2011;17(8):996–1002. doi: 10.1038/nm.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ulmer JB, DeWitt CM, Chastain M, et al. Enhancement of DNA vaccine potency using conventional aluminum adjuvants. Vaccine. 1999;18(1-2):18–28. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khosroshahi KH, Ghaffarifar F, Sharifi Z, et al. Comparing the effect of IL-12 genetic adjuvant and alum non-genetic adjuvant on the efficiency of the cocktail DNA vaccine containing plasmids encoding SAG-1 and ROP-2 of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology research. 2012;111(1):403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2852-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cristillo AD, Ferrari MG, Hudacik L, et al. Induction of mucosal and systemic antibody and T-cell responses following prime-boost immunization with novel adjuvanted human immunodeficiency virus-1-vaccine formulations. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 1):128–140. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.023242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karkada M, Weir GM, Quinton T, Fuentes-Ortega A, Mansour M. A liposome-based platform, VacciMax, and its modified water-free platform DepoVax enhance efficacy of in vivo nucleic acid delivery. Vaccine. 2010;28(38):6176–6182. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu J, Wu J, Wang B, et al. Oral vaccination with a liposome-encapsulated influenza DNA vaccine protects mice against respiratory challenge infection. Journal of medical virology. 2014;86(5):886–894. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma J, Wang H, Zheng X, et al. CpG/Poly (I:C) mixed adjuvant priming enhances the immunogenicity of a DNA vaccine against eastern equine encephalitis virus in mice. International immunopharmacology. 2014;19(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oldenburg M, Kruger A, Ferstl R, et al. TLR13 recognizes bacterial 23S rRNA devoid of erythromycin resistance-forming modification. Science. 2012;337(6098):1111–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1220363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen J, Lindenstrom T, Lindberg-Levin J, Aagaard C, Andersen P, Agger EM. CAF05: cationic liposomes that incorporate synthetic cord factor and poly(I:C) induce CTL immunity and reduce tumor burden in mice. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2012;61(6):893–903. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sajadian A, Tabarraei A, Soleimanjahi H, Fotouhi F, Gorji A, Ghaemi A. Comparing the effect of Toll-like receptor agonist adjuvants on the efficiency of a DNA vaccine. Archives of virology. 2014;159(8):1951–1960. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang M, Yao J, Feng G. Protective effect of DNA vaccine encoding pseudomonas exotoxin A and PcrV against acute pulmonary P. aeruginosa Infection. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu J, Jiang S, Ye S, Deng Y, Ma S, Li CP. CpG oligodeoxynucleotide ligand potentiates the activity of the pVAX1-Sj26GST. Biomedical reports. 2013;1(4):609–613. doi: 10.3892/br.2013.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu YZ, Ma Y, Xu WH, Wang S, Sun ZW. Combinations of various CpG motifs cloned into plasmid backbone modulate and enhance protective immunity of viral replicon DNA anthrax vaccines. Medical microbiology and immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00430-014-0359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luke JM, Simon GG, Soderholm J, et al. Coexpressed RIG-I agonist enhances humoral immune response to influenza virus DNA vaccine. Journal of virology. 2011;85(3):1370–1383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01250-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martinez-Gil L, Goff PH, Hai R, Garcia-Sastre A, Shaw ML, Palese P. A Sendai virus-derived RNA agonist of RIG-I as a virus vaccine adjuvant. Journal of virology. 2013;87(3):1290–1300. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02338-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Imanishi T, Ishihara C, Badr Mel S, et al. Nucleic acid sensing by T cells initiates Th2 cell differentiation. Nature communications. 2014;5:3566. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lladser A, Mougiakakos D, Tufvesson H, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) as a genetic adjuvant for DNA vaccines that promotes effective antitumor CTL immunity. Mol Ther. 2011;19(3):594–601. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Geissler M, Gesien A, Tokushige K, Wands JR. Enhancement of cellular and humoral immune responses to hepatitis C virus core protein using DNA-based vaccines augmented with cytokine-expressing plasmids. J Immunol. 1997;158(3):1231–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nobiron I, Thompson I, Brownlie J, Collins ME. Co-administration of IL-2 enhances antigen-specific immune responses following vaccination with DNA encoding the glycoprotein E2 of bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Veterinary microbiology. 2000;76(2):129–142. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hu H, Tao L, Wang Y, Chen L, Yang J, Wang H. Enhancing immune responses against SARS-CoV nucleocapsid DNA vaccine by co-inoculating interleukin-2 expressing vector in mice. Biotechnology letters. 2009;31(11):1685–1693. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-0061-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim JJ, Nottingham LK, Wilson DM, et al. Engineering DNA vaccines via co-delivery of co-stimulatory molecule genes. Vaccine. 1998;16(19):1828–1835. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim JJ, Simbiri KA, Sin JI, et al. Cytokine molecular adjuvants modulate immune responses induced by DNA vaccine constructs for HIV-1 and SIV. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 1999;19(1):77–84. doi: 10.1089/107999099314441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moore AC, Kong WP, Chakrabarti BK, Nabel GJ. Effects of antigen and genetic adjuvants on immune responses to human immunodeficiency virus DNA vaccines in mice. Journal of virology. 2002;76(1):243–250. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.243-250.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henke A, Rohland N, Zell R, Wutzler P. Co-expression of interleukin-2 by a bicistronic plasmid increases the efficacy of DNA immunization to prevent influenza virus infections. Intervirology. 2006;49(4):249–252. doi: 10.1159/000092487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barouch DH, Santra S, Steenbeke TD, et al. Augmentation and suppression of immune responses to an HIV-1 DNA vaccine by plasmid cytokine/Ig administration. J Immunol. 1998;161(4):1875–1882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barouch DH, Truitt DM, Letvin NL. Expression kinetics of the interleukin-2/immunoglobulin (IL-2/Ig) plasmid cytokine adjuvant. Vaccine. 2004;22(23-24):3092–3097. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barouch DH, Santra S, Schmitz JE, et al. Control of viremia and prevention of clinical AIDS in rhesus monkeys by cytokine-augmented DNA vaccination. Science. 2000;290(5491):486–492. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu C, Yu M, Gao S, Zeng Y, You X, Wu Y. [Protective immune responses induced by intranasal immunization with Mycoplasma pneumoniae P1C-IL-2 fusion DNA vaccine in mice] Xi bao yu fen zi mian yi xue za zhi = Chinese journal of cellular and molecular immunology. 2013;29(6):585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qin Y, Tian H, Wang G, Lin C, Li Y. A BCR/ABL-hIL-2 DNA vaccine enhances the immune responses in BALB/c mice. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:136492. doi: 10.1155/2013/136492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bhaumik S, Basu R, Sen S, Naskar K, Roy S. KMP-11 DNA immunization significantly protects against L. donovani infection but requires exogenous IL-12 as an adjuvant for comparable protection against L. major. Vaccine. 2009;27(9):1306–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamanaka H, Hoyt T, Yang X, et al. A nasal interleukin-12 DNA vaccine coexpressing Yersinia pestis F1-V fusion protein confers protection against pneumonic plague. Infection and immunity. 2008;76(10):4564–4573. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00581-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang SH, Lee CG, Park SH, et al. Correlation of antiviral T-cell responses with suppression of viral rebound in chronic hepatitis B carriers: a proof-of-concept study. Gene Ther. 2006;13(14):1110–1117. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Naderi M, Saeedi A, Moradi A, et al. Interleukin-12 as a genetic adjuvant enhances hepatitis C virus NS3 DNA vaccine immunogenicity. Virologica Sinica. 2013;28(3):167–173. doi: 10.1007/s12250-013-3291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao HG, Huang FY, Guo JL, Tan GH. Evaluation on the immune response induced by DNA vaccine encoding MIC8 co-immunized with IL-12 genetic adjuvant against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Zhongguo ji sheng chong xue yu ji sheng chong bing za zhi = Chinese journal of parasitology & parasitic diseases. 2013;31(4):284–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li J, Valentin A, Kulkarni V, et al. HIV/SIV DNA vaccine combined with protein in a co-immunization protocol elicits highest humoral responses to envelope in mice and macaques. Vaccine. 2013;31(36):3747–3755. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kalams SA, Parker SD, Elizaga M, et al. Safety and comparative immunogenicity of an HIV-1 DNA vaccine in combination with plasmid interleukin 12 and impact of intramuscular electroporation for delivery. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;208(5):818–829. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoon HA, Aleyas AG, George JA, et al. Cytokine GM-CSF genetic adjuvant facilitates prophylactic DNA vaccine against pseudorabies virus through enhanced immune responses. Microbiology and immunology. 2006;50(2):83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lu H, Xu XF, Gao N, Fan DY, Wang J, An J. Preliminary evaluation of DNA vaccine candidates encoding dengue-2 prM/E and NS1: their immunity and protective efficacy in mice. Molecular immunology. 2013;54(2):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lena P, Villinger F, Giavedoni L, Miller CJ, Rhodes G, Luciw P. Co-immunization of rhesus macaques with plasmid vectors expressing IFN-gamma, GM-CSF, and SIV antigens enhances anti-viral humoral immunity but does not affect viremia after challenge with highly pathogenic virus. Vaccine. 2002;20(Suppl 4):A69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.O'Neill E, Martinez I, Villinger F, et al. Protection by SIV VLP DNA prime/protein boost following mucosal SIV challenge is markedly enhanced by IL-12/GM-CSF co-administration. J Med Primatol. 2002;31(4-5):217–227. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2002.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen H, Gao N, Wu J, et al. Variable effects of the co-administration of a GM-CSF-expressing plasmid on the immune response to flavivirus DNA vaccines in mice. Immunology letters. 2014;162(1 Pt A):140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97*.Hellerstein M, Xu Y, Marino T, et al. Co-expression of HIV-1 virus-like particles and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor by GEO-D03 DNA vaccine. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2012;8(11):1654–1658. doi: 10.4161/hv.21978. GM-CSF is not always positive in increasing immunogenicity of DNA vaccines. Fine-tuning and appropriate expression level is important for using plasmid-encoded cytokines as molecular adjuvants. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bergamaschi C, Kulkarni V, Rosati M, et al. Intramuscular delivery of heterodimeric IL-15 DNA in macaques produces systemic levels of bioactive cytokine inducing proliferation of NK and T cells. Gene Ther. 2015;22(1):76–86. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen J, Li ZY, Huang SY, et al. Protective efficacy of Toxoplasma gondii calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 (TgCDPK1) adjuvated with recombinant IL-15 and IL-21 against experimental toxoplasmosis in mice. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14:487. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li ZY, Chen J, Petersen E, et al. Synergy of mIL-21 and mIL-15 in enhancing DNA vaccine efficacy against acute and chronic Toxoplasma gondii infection in mice. Vaccine. 2014;32(25):3058–3065. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Su B, Wang J, Zhao G, Wang X, Li J, Wang B. Sequential administration of cytokine genes to enhance cellular immune responses and CD4 (+) T memory cells during DNA vaccination. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2012;8(11):1659–1667. doi: 10.4161/hv.22105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Saade F, Petrovsky N. Technologies for enhanced efficacy of DNA vaccines. Expert review of vaccines. 2012;11(2):189–209. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chu D, Moroda M, Piao LX, Aosai F. CTL induction by DNA vaccine with Toxoplasma gondii-HSP70 gene. Parasitology international. 2014;63(2):408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhou J, Cheung AK, Tan Z, et al. PD1-based DNA vaccine amplifies HIV-1 GAG-specific CD8+ T cells in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(6):2629–2642. doi: 10.1172/JCI64704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liniger M, Summerfield A, Ruggli N. MDA5 can be exploited as efficacious genetic adjuvant for DNA vaccination against lethal H5N1 influenza virus infection in chickens. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e49952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Castaldello A, Sgarbanti M, Marsili G, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-1 acts as a powerful adjuvant in tat DNA based vaccination. Journal of cellular physiology. 2010;224(3):702–709. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shedlock DJ, Tingey C, Mahadevan L, et al. Co-Administration of Molecular Adjuvants Expressing NF-Kappa B Subunit p65/RelA or Type-1 Transactivator T-bet Enhance Antigen Specific DNA Vaccine-Induced Immunity. Vaccines. 2014;2(2):196–215. doi: 10.3390/vaccines2020196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen LP, Zhang RB, Hu D, et al. [Immune regulation of T-bet adjuvant on Ag85B DNA vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis] Xi bao yu fen zi mian yi xue za zhi = Chinese journal of cellular and molecular immunology. 2012;28(7):680–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hu D, Wu J, Zhang R, Chen L. T-bet acts as a powerful adjuvant in Ag85B DNAbased vaccination against tuberculosis. Molecular medicine reports. 2012;6(1):139–144. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Peng J, Zhao Y, Mai J, Guo W, Xu Y. Short noncoding DNA fragment improve efficiencies of in vivo electroporation-mediated gene transfer. The journal of gene medicine. 2012;14(9-10):563–569. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Peng J, Shi S, Yang Z, et al. Short noncoding DNA fragments improve the immune potency of electroporation-mediated HBV DNA vaccination. Gene Ther. 2014;21(7):703–708. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lares MR, Rossi JJ, Ouellet DL. RNAi and small interfering RNAs in human disease therapeutic applications. Trends in biotechnology. 2010;28(11):570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Geiben-Lynn R, Frimpong-Boateng K, Letvin NL. Modulation of plasmid DNA vaccine antigen clearance by caspase 12 RNA interference potentiates vaccination. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2011;18(4):533–538. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00390-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang ST, Chang CC, Yen MC, et al. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Foxo3 in antigen-presenting cells as a strategy for the enhancement of DNA vaccine potency. Gene Ther. 2011;18(4):372–383. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kim JH, Kang TH, Noh KH, et al. Blocking the immunosuppressive axis with small interfering RNA targeting interleukin (IL)-10 receptor enhances dendritic cell-based vaccine potency. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2011;165(2):180–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Jiang W. Blockade of B7-H1 enhances dendritic cell-mediated T cell response and antiviral immunity in HBV transgenic mice. Vaccine. 2012;30(4):758–766. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pradhan P, Qin H, Leleux JA, et al. The effect of combined IL10 siRNA and CpG ODN as pathogen-mimicking microparticles on Th1/Th2 cytokine balance in dendritic cells and protective immunity against B cell lymphoma. Biomaterials. 2014;35(21):5491–5504. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nemunaitis J, Barve M, Orr D, et al. Summary of bi-shRNA/GM-CSF augmented autologous tumor cell immunotherapy (FANG) in advanced cancer of the liver. Oncology. 2014;87(1):21–29. doi: 10.1159/000360993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Almeida RR, Raposo RA, Coirada FC, et al. Modulating APOBEC expression enhances DNA vaccine immunogenicity. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/icb.2015.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen YZ, Ruan GX, Yao XL, et al. Co-transfection gene delivery of dendritic cells induced effective lymph node targeting and anti-tumor vaccination. Pharmaceutical research. 2013;30(6):1502–1512. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-0985-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nature reviews Cancer. 2012;12(4):265–277. doi: 10.1038/nrc3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liu H, Moynihan KD, Zheng Y, et al. Structure-based programming of lymph-node targeting in molecular vaccines. Nature. 2014;507(7493):519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature12978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Toke ER, Lorincz O, Csiszovszki Z, et al. Exploitation of Langerhans cells for in vivo DNA vaccine delivery into the lymph nodes. Gene Ther. 2014;21(6):566–574. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ye C, Choi JG, Abraham S, Shankar P, Manjunath N. Targeting DNA vaccines to myeloid cells using a small peptide. European journal of immunology. 2015;45(1):82–88. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cao J, Jin Y, Li W, et al. DNA vaccines targeting the encoded antigens to dendritic cells induce potent antitumor immunity in mice. BMC immunology. 2013;14:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-14-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fossum E, Grodeland G, Terhorst D, et al. Vaccine molecules targeting Xcr1 on cross-presenting DCs induce protective CD8 T-cell responses against influenza virus. European journal of immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eji.201445080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Moulin V, Morgan ME, Eleveld-Trancikova D, et al. Targeting dendritic cells with antigen via dendritic cell-associated promoters. Cancer gene therapy. 2012;19(5):303–311. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Corbett AJ, Caminschi I, McKenzie BS, et al. Antigen delivery via two molecules on the CD8- dendritic cell subset induces humoral immunity in the absence of conventional “danger”. European journal of immunology. 2005;35(10):2815–2825. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Daftarian P, Kaifer AE, Li W, et al. Peptide-Conjugated PAMAM Dendrimer as a Universal DNA Vaccine Platform to Target Antigen-Presenting Cells. Cancer research. 2011;71(24):7452–7462. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]