Abstract

Background

Vincristine, a widely used chemotherapeutic agent, often induces painful peripheral neuropathy and there are currently no effective drugs to prevent or treat this side effect. Previous studies have shown that methylcobalamin has potential analgesic effect in diabetic and chronic compression of dorsal root ganglion model; however, whether methylcobalamin has effect on vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy is still unknown.

Results

We found that vincristine-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, accompanied by a significant loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers in the plantar hind paw skin and an increase in the incidence of atypical mitochondria in the sciatic nerve. Moreover, in the spinal dorsal horn, the activity of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and the protein expression of p-p65 as well as tumor necrosis factor α was increased, whereas the protein expression of IL-10 was decreased following vincristine treatment. Furthermore, intraperitoneal injection of methylcobalamin could dose dependently attenuate vincristine-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, which was associated with intraepidermal nerve fibers rescue, and atypical mitochondria prevalence decrease in the sciatic nerve. Moreover, methylcobalamin inhibited the activation of NADPH oxidase and the downstream NF-κB pathway. Production of tumor necrosis factor α was also decreased and production of IL-10 was increased in the spinal dorsal horn following methylcobalamin treatment. Intrathecal injection of Phorbol-12-Myristate-13-Acetate, a NADPH oxidase activator, could completely block the analgesic effect of methylcobalamin.

Conclusions

Methylcobalamin attenuated vincrinstine-induced neuropathic pain, which was accompanied by inhibition of intraepidermal nerve fibers loss and mitochondria impairment. Inhibiting the activation of NADPH oxidase and the downstream NF-κB pathway, resulting in the rebalancing of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the spinal dorsal horn might also be involved. These findings might provide potential target for preventing vincristine-induced neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain (CINP), mitochondrial dysfunction, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), intraepidermal nerve fiber (IENF) degeneration

Background

Chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain (CINP) is a common, dose-limiting side effect of cancer chemotherapeutic agents which include platinum drugs, proteasome inhibitors, as well as the vinca alkaloids such as vincristine.1 The symptoms may include early posttreatment pain, such as the paclitaxel-induced acute pain syndrome, paraesthesias, sensory ataxia, and mechanical and cold allodynia.2 CINP limits the duration of treatment and impairs the quality of life.3 Many preventive and treatment strategies have been explored; however, the results were conflicting and overall inconclusive.4 For example, only a few clinical trials have shown that tricyclic antidepressant, which are used to treat other types of painful neuropathy, can bring benefit to CINP.5 Several blockers of CaV and NaV channels, such as lamotrigine and gabapentin, have also failed to ameliorate CINP in clinical trials.6 Also no beneficial effects of other interventions, such as calcium and magnesium infusion, have been observed.7–9 Hence, an alternative or novel approach is in need to treat or prevent CINP.

Vincristine possesses neurotoxicity as well as anticancer action due to its binding towards neuronal cytoskeleton protein (β-tubulin) and disruptive action in polymerization of microtubules. Different from painful peripheral neuropathies induced by trauma or diabetes, there is no axonal degeneration at the peripheral nerve in vincristine-treated rats10,11; however, there is a partial degeneration that is confined to the intraepidermal sensory terminal arbors in rats with vincristine-evoked pain.12 This degeneration may lead to abnormal spontaneous discharge, which is critical for the development of neuropathic pain after vincristine treatment.13 Therefore, intraepidermal nerve fiber (IENF) loss correlate directly with pain behaviors in rats and is suggested to be a key CINP mechanism.14,15 IENF degeneration and abnormal spontaneous discharge of primary afferent nerve fibers may be strengthened by mitochondrial dysfunction and consequent energy deficiency,16 as the energy deficiency will cause impairment of electrogenic Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase-dependent pump, which then lead to axonal membrane depolarization and the generation of spontaneous action potentials.17 Consistent with the above studies, treatment with acetyl-L-carnitine, a drug, enhances mitochondrial function can prevent the development of CINP induced by vincristine.18

Studies have shown that glia activation and pronociceptive substances such as proinflammatory interleukins and TNF-α in the spinal cord contribute to vincristine-induced neuropathic pain.19–21 Other factors, such as oxidative stress22 and dysregulation of calcium homoeostasis,23 have also been reported to be attributed to the development of vincristine-induced neuropathic pain.

Methylcobalamin (MeCbl), a form of vitamin B12 that contains cobalt, has a strong affinity for nerve tissues.24 As MeCbl is important for normal functioning of the nervous system, its deficiency causes a systemic neuropathy called subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord.25 MeCbl can also significantly enhance the de novo DNA methylation, which has been reported to modulate nociceptive sensitization induced by incision26 or chronic constriction injury27 in rats. Currently, MeCbl is used to treat diabetic peripheral neuropathy28,29 and some other nervous diseases including Alzheimer’s disease.30 A line of evidence has shown that MeCbl treatment ameliorates mechanical allodynia induced by chronic compression of dorsal root ganglion (CCD),31 but another study also reports that MeCbl is ineffective in treating lumbar spinal stenosis-induced pain.32 Whether MeCbl could prevent vincristine-induced painful neuropathy and the mechanisms are still unclear.

In the present study, we first tested whether intraperitoneal injection of MeCbl could attenuate vincristine-induced neuropathic pain. Then, we investigated whether MeCbl had effect on the density of IENF in the glabrous skin of hind paw and on the prevalence of atypical mitochondria in the sciatic nerve. Furthermore, we investigated whether MeCbl affect vincristine-induced neuropathic pain via NADPH oxidase activation in the spinal dorsal horn. The effects of MeCbl on the subsequent NF-κB pathway as well as the expression of cytokines in the spinal dorsal horn were also investigated.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats weighing 180 g to 200 g were used. The rats were housed in separated cages and the room was kept at 24 ± 1℃ temperature and 50% to 60% humidity, under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle and with ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Local Animal Care Committee and were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health on animal care and the ethical guidelines for investigation of experimental pain in conscious animal.33

Drugs

For the behavioral experiments, Vincristine sulfate (Main Luck Pharmaceuticals Inc. Shenzhen, China) dissolved with saline to a concentration of 50 µg/ml was intraperitoneally injected at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg daily for 10 consecutive days.12,34 Control animals received an equivalent volume of saline. Dosage of MeCbl injection solution (Eisai, Co., Ltd. Japan) was administrated intraperitoneally 15 days before vincristine, and then every other day thereafter until the ninth day after the last vincristine injection. MeCbl was administrated 30 min before vincristine injection. Phorbol-12-Myristate-13-Acetate (PMA) was purchased by Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Intrathecal injection

Intrathecal catheters were implanted according to the method described previously.35 Briefly, under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (40 mg/kg, i.p.), a sterile PE-10 tube filled with saline was inserted through L5/L6 intervertebrae space, and the tip of the tube was placed at the spinal lumbar enlargement level. A complete hemostasis was confirmed and the wound was sutured in two layers. The rats with hind limb paralysis or paresis after surgery were excluded. The successful catheterization was confirmed by bilateral hind limb paralysis following injection of 2% lidocaine (7 µl) through the catheter within 30 s. Drugs or vehicle were administered in volumes of 5 μl followed by a flush of 10 μl of saline to ensure drugs delivered into the subarachnoid space.

Behavioral tests

Mechanical allodynia

Mechanical sensitivity was assessed with the up–down method described previously,36 using a set of von Frey hairs with logarithmically incremental stiffness from 0.6 g to 15 g (0.6, 1, 1.4, 2, 4, 6, 8, 15 g). The 2 g stimulus, in the middle of the series, was applied first. In the event of paw withdrawal absence, the next stronger stimulus was chosen. On the contrary, a weaker stimulus was applied. Each stimulus consisted of a 6 to 8 s application of the von Frey hair to the sciatic innervation area of the hind paws with a 5-min interval between stimuli. The quick withdrawal or licking on the paw in response to the stimulus was considered as a positive response.

Thermal hyperalgesia

Heat hypersensitivity was tested using the plantar test (7370, UgoBasile, Comeria, Italy) according to the method described by Hargreaves et al.37 Briefly, a radiant heat source beneath a glass floor was aimed at the fat part of the heel on plantar surface of the hind paw. The nociceptive withdrawal reflex interrupts the light reflected from the hind paw onto a photocell and automatically turns off the light and a timer. The intensity of the light was adjusted at the start of the experiment such that average baseline latencies were about 22 s and a cut-off latency of 25 s was imposed. Four measurements of latency were taken for each hind paw in each test session. The hind paw was tested alternately with greater than 5 min intervals. The four measurements of latency per side were averaged as the result of per test. The experimenter who conducted the behavioral tests was blinded to all treatments.

Immunohistochemistry

Rats were perfused through the ascending aorta with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2–7.4, 4℃. The glabrous skin of hind paw was excised and post-fixed in the same fixative for 3 h and then replaced with 30% sucrose overnight. Cryostat sections (16 µm) were cut and processed for immunohistochemical staining as previously described.35 Sections were blocked with 3% donkey serum for 1 h at the room temperature, and then incubated overnight at 4℃ with rabbit anti-protein gene product 9.5 primary antibody (PGP9.5, 1:2000, Chemicon) for skin. After rinsing three times with PBS, sections were incubated in donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody labeled with Cy3 (1:500, Jackson) for 1 h at a room temperature. Five rats were included for each group for immunohistochemistry quantification. The stained sections were examined with a Leica (Leica, Germany) fluorescence microscope and images were captured with a Leica DFC350 FX camera. All IENF counts were done by an observer blind as to the animal’s group assignment. All ascending nerve fibers that were seen to cross into the epidermis were counted, no minimum length was required and fibers that branched within the epidermis were counted as one.38,39 IENF density was determined as the total number of fibers/length of epidermis (IENFs/mm). To confirm the specificity of the primary antibody, control sections were incubated without primary antiserum. One section of skin (8–12 mm long) was analyzed for each rat. Five rats were included for each group for immunohistochemistry quantification.

Assessment of mitochondrial abnormalities by transmission electron microscope

Rats were overdosed with sodium pentobarbital. Sciatic nerve segments of 6 mm length were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) overnight at 4℃. The fixed nerves were postfixed with 2% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at 25℃, dehydrated in a graded alcohol series, and embedded in Epon812. Thin sections (1 µm) were cut from each block, stained with alkaline toluidine blue, and examined by light microscopy. Ultrathin sections (80 nm thick) were cut with an ultramicrotome (Leica, EMUC6, German), and then stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for 30 min and 5 min as previously described.40 Electron photomicrographs were taken for analysis at 3300× for orientation and at 37,000× for counts of mitochondria. The analysis and quantification were performed by an observer who was blind as to group assignment. In order to obtain random samples of unmyelinated and myelinated axons, Remak bundles that had the nuclei of their Schwann cells (nucleated Remak bundles, NRBs) in the plane of section were identified at low magnification (3300×). The search for NRBs began at one randomly chosen hole of the grid and progressed through each hole in succession. All C-fibers within each NRB were photographed in their entirety at 37,000×. Myelinated axons that surrounded the selected NRBs were photographed at the same magnification. Each myelinated axon was imaged in its entirety. NRBs were selected one by one until more than 60 C-fibers and 60 myelinated axons per animal had been photographed. Swollen and vacuolated mitochondria were identified as described previously.41

Measurement of NADPH oxidase activity

Spinal cord tissues (L4–L6) were homogenized in HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH 7.5, containing 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EGTA, 25 mM potassium chloride, 10 µg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, 2 µg/mL aprotinin, and 10 µg/mL leupeptin) and centrifuged at 1000 g to obtain the nuclear-free supernatants. The NADPH cytochrome c reductase activity in these supernatants was measured using Cytochrome c Reductase (NADPH) Assay Kit (Sigma Aldrich) as previously described.42

Western blotting

The dorsal quadrants of L4–L6 spinal cord were harvested from different groups of rats (three rats at each group). The dorsal side were separated and put into liquid nitrogen immediately, followed by homogenization in 15 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.6, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The tissues were sonicated on ice and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4℃ to isolate the supernatant containing protein samples. Proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, USA). The blots were blocked with 5% w/v nonfat dry milk in TBST (20 mM Tris-base, pH 7.5, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies, including NF-κB p65 (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (p-p65, Ser536) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), TNF-α (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), IL-10 (1:500; Abcam) mouse monoclonal β-actin antibody (1:500), overnight at 4℃ with gentle shaking. The blots were washed four times for 10 min each with washing buffer (TBST) and then incubated with secondary antibody horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-goat or goat anti-mouse IgG (1:8000; Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation with the secondary antibody, the membrane was washed again as above. The blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Clarity™ Western ECL Substrate; Bio-Rad) and were detected by a Tanon 5200 imager (Tanon Science & Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). The intensities of the blots were quantified by Tanon MP (Tanon Science & Technology Co., Ltd) software and normalized against a loading control (β-actin).

Quantification and statistics

All data were expressed as means ± SEM. For the data of behavioral tests, nonparametric tests were employed in comparing between various testing days and various surgical groups. The data between testing days were analyzed with Friedman ANOVA for repeated measurements, followed by Wilcoxon matched pairs test when appropriate. The data between groups on a given testing day were analyzed with Mann–Whitney U test. The number of the fibers, the prevalence of atypical mitochondria, the relative densities of Western blots, and NADPH oxidase activity between different groups were compared using ANOVA with the least significant difference test (LSD-t). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check the normality of data. Data were considered normally distributed if p > 0.05. All analysis was done in a blinded fashion with the same criterion. Statistical tests were performed with SPSS 15.0. p < 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Results

Effects of MeCbl on vincristine-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia

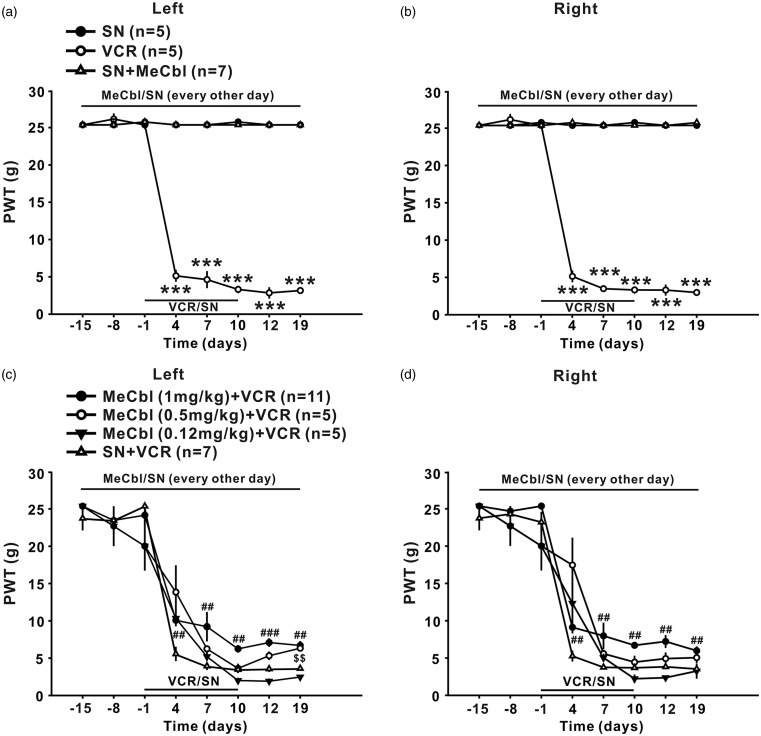

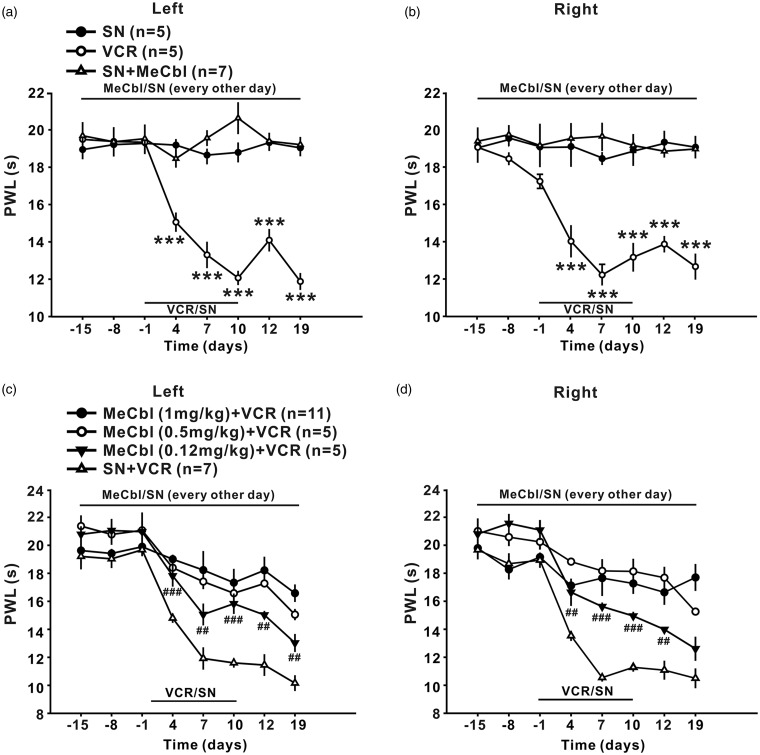

Intraperitoneal injection of vincristine (100 µg/kg for 10 consecutive days) led to persistent decrease in 50% paw withdrawal threshold (50% PWT) to mechanical stimulus (Figure 1(a) and (b), p < 0.001) and in paw withdrawal latencies (PWL) to radiant heat (Figure 2(a) and (b), p < 0.001), which lasted at least 19 days, indicating that mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia was induced. To test whether MeCbl may affect the development of mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, different doses of MeCbl (0.12, 0.5, and 1 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally, started 15 days before, and then every other day thereafter until the 19th day after onset of vincristine. As shown in Figure 1(c) and (d), compared to the vehicle-treated group, the 50% PWTs in the bilateral hind paw were significantly increased from day 4 to day 19 (p < 0.01 at day 4, 7, 10, and 19 and p < 0.001 at day 12 for the left hind paw; p < 0.01 at all the time tested for the right hind paw) in the 1 mg/kg MeCbl-treated group. 0.5 and 0.12 mg/kg MeCbl had no effect on the decrease of 50% PWTs in the bilateral hind paw (p > 0.05) except that 0.5 mg/kg MeCbl significantly increased the 50% PWTs on the left hind paw at day 19 after onset of vincristine (p < 0.01) (Figure 1(c) and (d)). These results indicate that 1 mg/kg Mecbl was most effective in inhibiting vincristine-induced mechanical allodynia, whereas the lower doses of Mecbl had minimal effect.

Figure 1.

Effects of MeCbl on mechanical allodynia produced by vincristine. (a) and (b) Intraperitoneal injection of vincristine (100 µg/kg for 10 consecutive days, n = 7) but not saline (n = 5) to rats induced persistent decrease in 50% PWT in bilateral hind paw, which lasted at least 19 days. MeCbl alone had no effect on the 50% PWT in saline-treated rats. (c) and (d) 1 mg/kg MeCbl injected intraperitoneally, started 15 days before, and then every other day thereafter until the 19th day after onset of vincristine significantly increased the bilateral 50% PWT (n = 11). MeCbl at the doses of 0.5 and 0.12 mg/kg had no effect on the decrease of 50% PWTs in the bilateral hind paw (p > 0.05) except that 0.5 mg/kg MeCbl significantly increased the 50% PWTs on the left hind paw at day 19 after onset of vincristine (p < 0.01). ***p < 0.001 compared with baseline; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, and $$p < 0.01 compared with vincristine-treated group. n = 5–11 for each group.

Figure 2.

Effects of MeCbl on thermal hyperalgesia produced by vincristine. (a) and (b) Intraperitoneal injection of vincristine (100 µg/kg for 10 consecutive days, n = 7) but not saline (n = 5) to rats induced persistent decrease in PWL in bilateral hind paw, which lasted at least 19 days. MeCbl alone had no effect on the paw withdrawal latency in saline-treated rats. (c) and (d) All the three doses of MeCbl that tested, including 1, 0.5, and 0.12 mg/kg significantly increased the bilateral paw withdrawal latency (n = 5 or 11). ***p < 0.001 compared with baseline; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, and $$p < 0.01 compared with vincristine-treated group. n = 5–11 for each group.

MeCbl was more effective for inhibition of thermal hyperalgesia, as the difference of bilateral paw withdrawal latencies between 0.12 mg/kg MeCbl-treated group and vehicle-treated group was significant from day 4 to day 19 after onset of vincristine (p < 0.05 at day 4, 7, and 19; p < 0.01 at day 12; p < 0.001 at day 10 for the left hind paw; p < 0.05 at day 4 and 12; p < 0.01 at day 10; p < 0.001 at day 7 for the right hind paw), as shown in Figure 2(c) and (d). After 1 mg/kg MeCbl treatment, the paw withdrawal latency was enhanced to the baseline level (p > 0.05), indicating that this dose of Mecbl could block the development of thermal hyperalgesia completely.

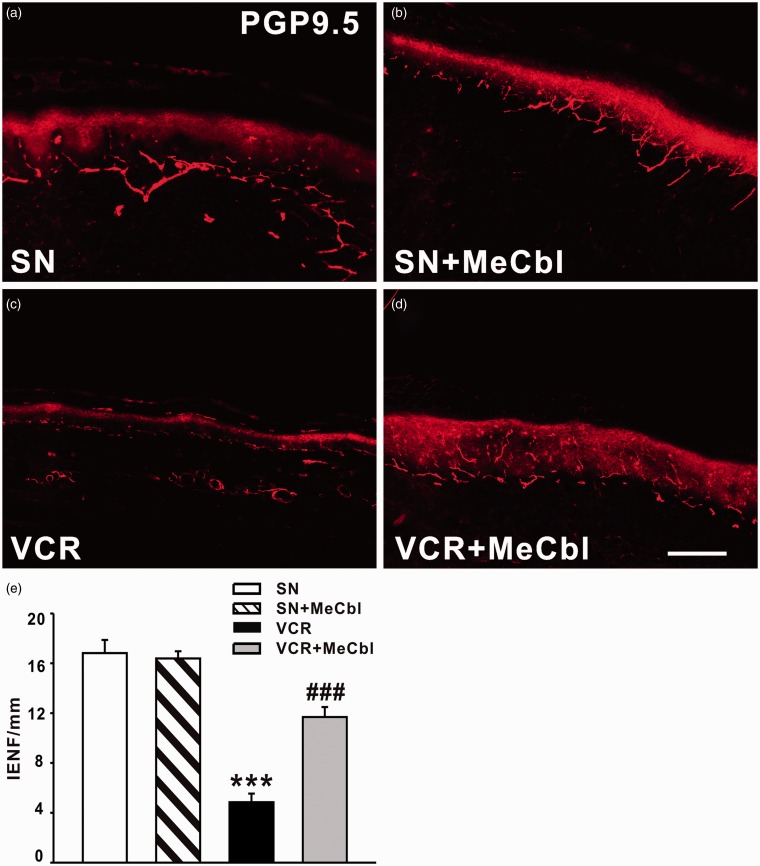

MeCbl rescued the loss of IENF induced by vincristine

We next examined whether MeCbl could rescue the loss of IENF induced by vincristine. As shown in Figure 3, PGP9.5-labeled IENF emerged from cutaneous nerves and traveled vertically into the epidermis where they branched into terminal. Nineteen days after vincristine treatment, a significant loss of IENFs was found (Figure 3(c)). As shown in Figure 3(e), the number of IENFs per millimeter decreased from 16.82 ± 1.06 in saline-treated group to 4.85 ± 0.70 (p < 0.001) in vincristine-treated rats. However, application of 0.5 mg/kg MeCbl significantly inhibited the loss of IENFs induced by vincristine on day 19 (11.69 ± 0.80, p < 0.001). Moreover, MeCbl alone (16.39 ± 0.57) did not affect the density of IENF, compared with saline-treated rats (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 3.

Effect of intraperitoneal injection of MeCbl on loss of IENF induced by vincristine. (a) PGP9.5-labeled IENF emerged from cutaneous nerves and traveled vertically into the epidermis where they branched into terminals. (b) MeCbl alone did not affect the density of IENF in saline-treated rats. (c) A significant loss of IENF was found on day 19 after vincristine treatment. (d) 0.5 mg/kg MeCbl significantly inhibited the loss of IENF induced by vincristine on day 19. ***p < 0.001 compared with saline-treated group. ###p < 0.001 compared to the vincristine-treated group. n = 5 for each group. Scale bar: 100 µm.

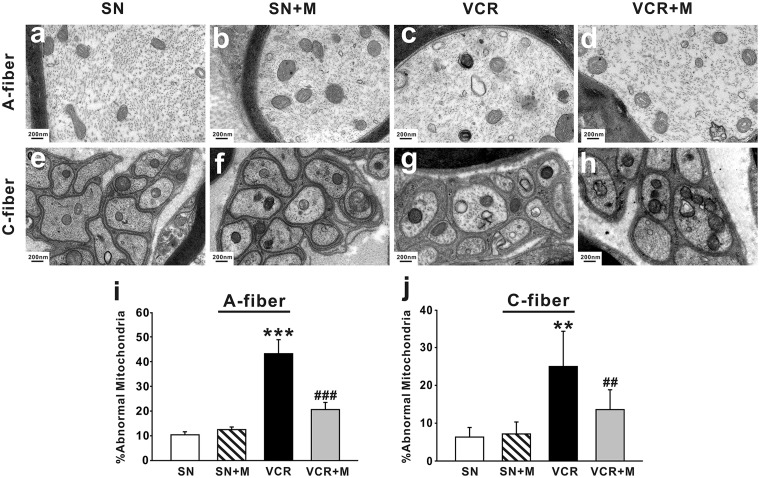

MeCbl decreased the mitochondrial abnormalities in axons of the sciatic nerve associated with vincristine treatment

Normal and atypical (swollen and vacuolated) mitochondria were observed in both myelinated axons (Figure 4(a)) and C-fibers (Figure 4(e)) of saline-treated nerves. We found by electron microscope that MeCbl could exert protective effect on mitochondria. The results showed that 19 days after onset of vincristine treatment, the prevalence of atypical mitochondria in myelinated A-fibers (Figure 4(c), p < 0.001 compared with saline-treated group) and C-fibers (Figure 4(g), p < 0.01 compared with saline-treated group) of vincristine-treated nerves was 43.83% ± 3.80 and 24.99% ± 9.32, respectively. In saline-treated rats, 12.9% ± 2.31 of A-fibers (Figure 4(a)) and 6.32% ± 2.53 (Figure 4(b)) of C-fibers mitochondria were atypical. The increased abnormality of axonal mitochondria may contribute to vincristine-induced pain. Application of 0.5 mg/kg MeCbl significantly decreased the prevalence of atypical mitochondria in A- (Figure 4(d), 22.28% ± 1.81) and C-fibers (Figure 4(h), 13.58% ± 5.25) 19 days after vincristine treatment. MeCbl alone had no significant effect on appearance of abnormal mitochondria in either A-fibers (Figure 4(b), 13.70% ± 1.90, p > 0.05 compared to the saline-treated group) or C-fibers (Figure 4(f), 7.15% ± 3.16, p > 0.05 compared to the saline-treated group).

Figure 4.

Effects of MeCbl on the prevalence of atypical mitochondria in A- and C- fiber. (a) to (h) Representative ultrastructural imaging showing the prevalence of atypical mitochondria in A- fiber (a–d) and C- fiber (e–h) from the four different groups as indicated. The histogram shows the summary data (n = 5/group, means ± SEM) of abnormal mitochondria on day 19 after onset of vincristine treatment. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with saline-treated group. ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 compared with vincristine-treated group. Scale bar: 200 nm. SN: saline-treated group; SN + M: saline and MeCbl-treated group; VCR: vincristine-treated group; VCR + M: vincristine and MeCbl-treated group.

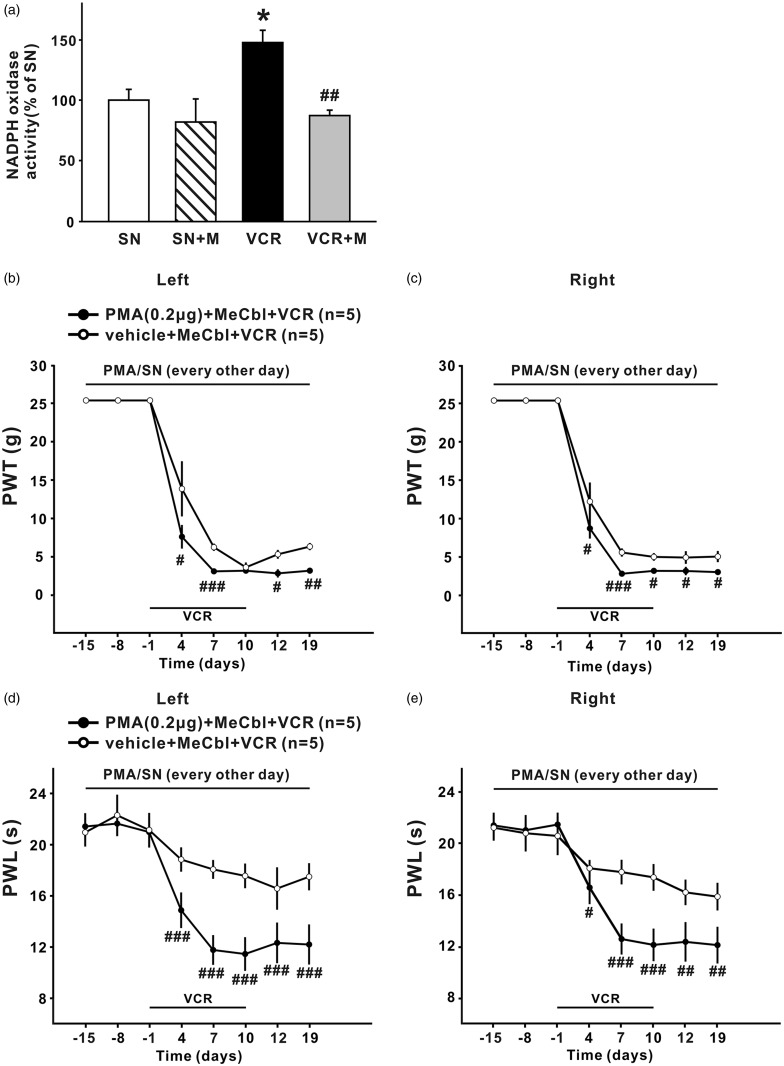

MeCbl inhibited spinal NADPH oxidase activation induced by vincristine, and the effect of MeCbl on vincristine-induced neuropathic pain was completely blocked by NADPH oxidase activator PMA

It has been reported that the development of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain is dependent upon activation of NADPH oxidase.42 In the present study, we found that NADPH oxidase was significantly activated 19 days after the first application of vincristine, indicating the superoxide production in the spinal cord was increased. Activation of NADPH oxidase induced by vincristine could be decreased to the baseline level after 0.5 mg/kg MeCbl treatment (p < 0.01 compared to the VCR group, and p > 0.05 compared to the saline-treated group) (Figure 5). This was associated with significant attenuation of mechanical allodynia (Figure 1(c)) and thermal hyperalgesia (Figure 2(c)). Further experiments showed that MeCbl alone had no effect on NADPH oxidase activation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

MeCbl inhibited the activation NADPH oxidase in spinal dorsal horn induced by vincristine, and intrathecal injection of NADPH oxidase activator blocked the effects of MeCbl on mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. (a) The histogram shows NADPH oxidase activity in the lumbar spinal dorsal horn from the four different groups, as indicated (n = 5/group, means ± SEM). (b) to (e) PMA (0.2 µg/5 µl) administrated intrathecally 10 min before MeCbl could block the inhibitory effect of MeCbl on the mechanical allodynia (b) to (c) and on thermal hyperalgesia (d) to (e) in bilateral hind paw. (a) *p < 0.05 compared with saline-treated group; ##p < 0.01 compared with vincristine- treated group; (b) to (e): #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 compared with vincristine-treated group that had received vehicle and MeCbl administration.

Next we tested whether activation of NADPH oxidase by intrathecal application of PMA could block the MeCbl’s effect. The results showed that intrathecal injection of PMA (0.2 µg/5 µl), but not the vehicle, 10 min before MeCbl, could completely block the effects of MeCbl on the decrease of 50% PWT (Figure 5(b) and (c)) and PWL (Figure 5(d) and (e)) induced by vincristine, indicating that MeCbl exerted its effect via inhibiting the NADPH oxidase activation in the spinal dorsal horn.

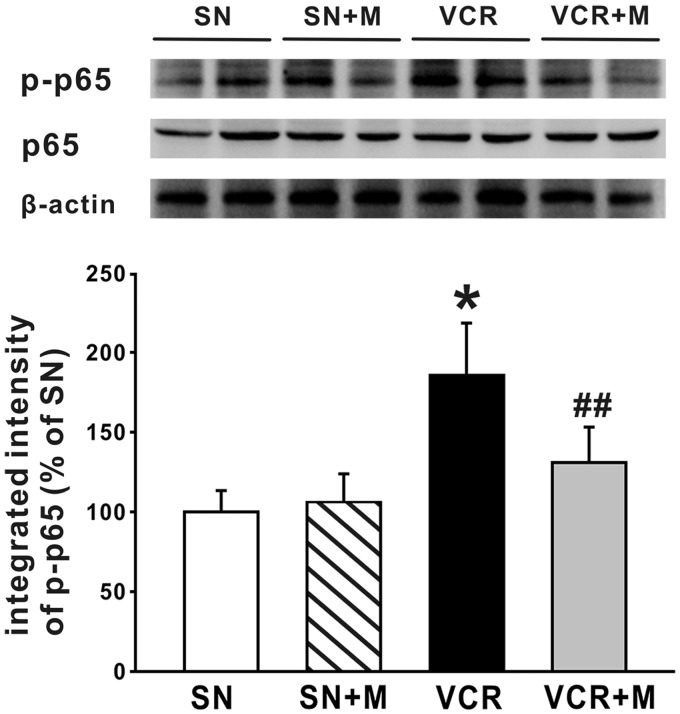

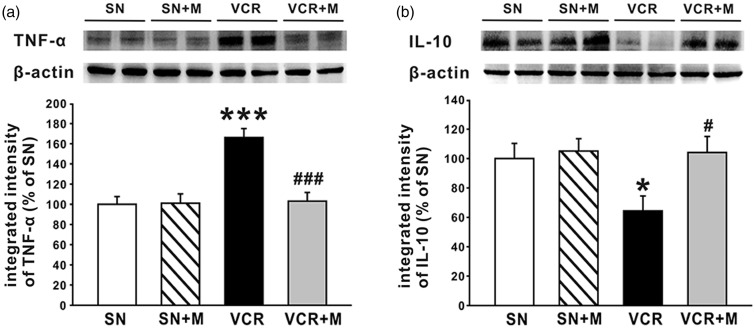

MeCbl inhibited the activation of NF-κB pathway, decreased the production of TNF-α, and increased the production of IL-10 in the spinal dorsal horn

NF-κB, in particular the classical or canonical pathway controlled by p65 or p50, has been shown to play a central role in CIPN.43 p65 is a principal transcriptional regulator of the canonical NF-κB pathway, and the increased expression of p-p65 reflects the activation of NF-κB, as NF-κB p65 requires phosphorylation prior to its binding to specific target genes in the nucleus.44,45 NF-κB has also been reported to regulate the expression of several cytokines.46 Accordingly, in the present work, we next investigated whether MeCbl affected the activation of NF-κB pathway by observing the expression of p-p65 in lumbar spinal cord with Western blot. The results showed that 19 days after the first application of vincristine, the expression of p-p65 (Figure 6) and TNF-α (Figure 7(a)) was significantly increased, indicating that NF-κB pathway was activated by vincristine, thus leading to overproduction of TNF-α. Further experiments showed that when compared to the saline-treated rats, the expression of p-p65 (Figure 6), as well as the overproduction of TNF-α (Figure 7(a)) was significantly decreased in the 0.5 mg/kg MeCbl-treated rats. Moreover, MeCbl increased the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, which was down-regulated by vincristine treatment (Figure 7(b)).

Figure 6.

Effects of MeCbl on the activation of NF-κB pathway in spinal dorsal horn induced. The bands show the expression of p-p65, p65, and β-actin from protein samples of bilateral lumbar spinal dorsal horn in saline (SN)-treated group, saline and MeCbl (SN + MeCbl)-treated group, vincristine (VCR)-treated group, and vincristine-treated group that had received MeCbl administration. The histogram shows the quantification of p-p65 normalized by β-actin (n = 6/group). *p < 0.05 compared with saline-treated group; ##p < 0.01 compared with vincristine-treated group.

Figure 7.

Effects of MeCbl on TNF-α overexpression and IL-10 downregulation in spinal dorsal horn induced. (a) The bands show the expression of TNF-α and β-actin from protein samples of bilateral lumbar spinal dorsal horn in the four groups (saline group, saline + MeCbl group, VCR group and MeCbl + VCR group). The histogram shows the quantification of TNF-α normalized by β-actin (n = 6/group). (b) The bands show the expression of IL-10 and β-actin from protein samples of bilateral lumbar spinal dorsal horn in the above four groups. The histogram shows the quantification of IL-10 normalized by β-actin (n = 6/group). *p < 0.05 compared with saline-treated group; #p < 0.05 compared with vincristine-treated group.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that treatment with MeCbl significantly inhibited the mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia induced by vincristine. This was associated with IENF rescue, and atypical mitochondria prevalence decrease in the sciatic nerve. MeCbl also inhibited the activation of NADPH oxidase and the downstream NF-κB pathway, resulting in decreased production of TNF-α and increased production of IL-10 in the spinal dorsal horn. Moreover, intrathecal injection of PMA, a NADPH oxidase activator, could significantly block the analgesic effect of MeCbl. These results indicated that MeCbl attenuated vincristine-induced neuropathic pain through inhibiting IENF loss and mitochondria impairment in the peripheral nerves. Inhibiting the activation of NADPH oxidase and the downstream NF-κB pathway, resulting in the rebalancing of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the spinal dorsal horn may also be involved.

The protective effect of MeCbl on CINP

Among the analogs, including cyanocobalamin (CNCbl), hydroxocobalamin (OHCbl), and adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl), MeCbl is the most effective one in being uptaken by subcellular organelles of neurons. MeCbl has been adopted to treat diabetic neuropathy47 and some other nervous diseases including Alzheimer’s disease.30 It has also been reported to promote nerve regeneration and myelination48 and to protect against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity.49,50 In the present study, we showed that intraperitoneal injection of MeCbl, one active form of vitamin B12 that can directly participate in homocysteine metabolism, dose-dependently inhibited the mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia induced by vincristine. The results are consistent with previous studies showing that continuous administration of MeCbl of high dose could ameliorate neuropathic pain associated with diabetic neuropathy51 or with CCD.31

Besides used alone, MeCbl is usually combined with other drugs, such as vitamin E.52 MeCbl, alpha lipoic acid, and pregabalin combination provides additional pain relief compared to pregabalin alone in type 2 diabetes mellitus associated peripheral neuropathy.53 Therefore either MeCbl combination or pure MeCbl has beneficial effects on pain symptoms.

In the present study, we found that MeCbl was more effective in inhibiting thermal hyperalgesia, as the lowest dose of MeCbl (0.12 mg/kg) significantly attenuated thermal hyperalgesia but had no effect on mechanical allodynia in vincristine-treated rats, and the highest dose of MeCbl (1 mg/kg) increased PWL to the radiant heat but not 50% PWT to the mechanical stimulus to the baseline level. These results are consistent with the previous study reports that intraperitoneal injection of CNCbl (B12, 0.5 and 2 mg/kg) significantly reduces thermal hyperalgesia but has no effect on mechanical hyperalgesia.54 The reason for the difference is still unknown and remains to be elucidated.

The possible mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effects of MeCbl on CINP

Enormous evidence has demonstrated that the spontaneous activities (ectopic discharges) in primary afferents are critical for the development of neuropathic pain55 induced by peripheral nerve injury56 as well as by vincristine treatment.13 Rats with vincristine-evoked neuropathic pain do not have axonal degeneration at the level of the peripheral nerve, as myelin structure was normal. However, they have a partial degeneration that is confined to the intraepidermal sensory terminal arbors, that is loss of IENF, which is proposed as a common lesion in various toxic neuropathies, as shown by the present and previous study.57 The intact axons, whose sensory terminal arbors have degenerated, either partly or completely, may lead to abnormal spontaneous discharge. A recent study has shown that MeCbl markedly inhibit the ectopic spontaneous discharges of dorsal root ganglion neurons in CCD rats.31 In the present study, we found that MeCbl could inhibit the loss of IENF, thus it is possible that MeCbl inhibit the ectopic discharge through ameliorating the loss of IENF, and at last attenuate vincristine-induced CINP.

In the present study, we found that increased atypical mitochondria prevalence induced by vincristine was also ameliorated by MeCbl. As IENF requires high energy supply from mitochondria, mitochondria impairment following CINP may lead to the energy shortage of IENF, which then cause the degeneration of IENF.57 MeCbl can be directly transferred into the nerve tissue, then stimulate the synthesis of axonal proteins. The synthesized axonal proteins can be anterogradely transported to the intraepidermal sensory terminal. Boosting the protein levels seems to compensate for the loss due to degeneration or increased exocytosis after vincristine treatment. Therefore, it is possible that MeCbl attenuated the loss of IENF induced by vincristine by protecting the mitochondria.

Pronociceptive cytokines, well known to activate the NF-κB pathway, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, are also demonstrated to be critically involved in the development of hyperalgesia and allodynia induced by vincristine.20,58,59 Hence, any agents that can attenuate these pronociceptive substances have been proved to be successful in attenuating neuropathic pain. For example, Greeshma22 has reported that tetrahydrocurcumin, a more bioavailable and/or potent metabolite that come from curcumin, could have protective effect on vincristine-induced CINP. In the present study, we showed that MeCbl not only inhibit the overproduction of TNF-α but also increased the expression of IL-10 in the spinal dorsal horn. IL-10, one of the most important anti-inflammatory cytokines, can not only suppress the production but also inhibit the activity of several proinflammatory mediators.60 Intrathecal IL-10 gene therapy attenuates paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia.61 In this line, the analgesic effect observed by MeCbl treatment in vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy can be justified.

Oxidative stress is another major contributor in the development of neuropathy in vincristine-treated rats, as oxidative stress can induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines.62 NADPH oxidase, a major enzyme involved in the production of ROS, can increase production of superoxide and enhance the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).63 Moreover, enhanced iNOS expression can lead to high generation of nitric oxide (NO), which then leads to tissue injury and do damage to cellular constituents through the generation of reactive nitrogen species, such as peroxynitrite.64 A recent study has shown that NADPH oxidase activation is a key in TLR4 recruitment into lipid rafts, which in turn up-regulates NF-κB translocation to the nucleus and subsequent DNA binding.65 NF-κB consists five structurally related members that include p65/RelA, c-Rel, RelB, p50, and p52, and these members can form homo- or hetero-dimers with each other.66 The p50/p65 heterodimer, the most abundant expressed forms of NF-κB, is bound to inhibitory proteins IκB in the cytoplasm and present in an inactive form in the unstimulated cells. Upon activation by varieties of stimuli, IκB is rapidly phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and then degraded, leading to the active heterodimer of p50/p65 translocate into nucleus, where it binds to specific κB sites and activates a variety of NF-κB target genes, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-18, and etc.67 Hence, the expression of p-p65 can reflect the activation of NF-κB pathway.44,45 In the present study, we showed that the expression of p-p65, a principal transcriptional regulator of the canonical NF-κB pathway, was inhibited by MeCbl, indicating that multiple NF-κB target genes, including TNF-α, are changed by MeCbl treatment.

In the present study, we found that the activation of NADPH oxidase was significantly increased in the spinal dorsal horn following vincristine treatment and that MeCbl could significantly inhibit this activation. Furthermore, the analgesic effect of MeCbl could be completely blocked by activation of NADPH oxidase by PMA. These results provide proof that MeCbl can inhibit vincristine-induced neuropathic pain by inhibiting NADPH oxidase activation. Though it is currently unknown how MeCbl inhibits NADPH oxidase activation, it is tempting to speculate that MeCbl inhibit the vincristine-induced neuropathic pain by attenuating the NADPH oxidase activation and the subsequent NF-κB pathway, and at last inhibit the neuroinflammation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our present data provided evidence that MeCbl could attenuate vincristine-induced neuropathic pain, likely due to its inhibition on loss of IENF and mitochondria impairment in the sciatic nerve. Inhibiting the activation of NADPH oxidase and NF-κB pathway, resulting in the rebalancing of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the spinal dorsal horn may also be involved. The finding might provide potential target for preventing vincristine-induced neuropathic pain.

Authors’ contributions

JX, WW, and XZ performed the study; JX, YF, and XW analyzed the experimental data; XW and XL designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U1201223, 81200856, 81471250), a grant from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 13ykpy05), and a grant from the Nature Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (No. 2014A030313029). We thank Eisai, Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) to supply MeCbl.

References

- 1.Quasthoff S, Hartung HP. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol 2002; 249: 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisignano M, Baron R, Scholich K, et al. Mechanism-based treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Neurol 2014; 10: 694–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf S, Barton D, Kottschade L, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: prevention and treatment strategies. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 1507–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brami C, Bao T, Deng G. Natural products and complementary therapies for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016; 98: 325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pachman DR, Watson JC, Loprinzi CL. Therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment related peripheral neuropathies. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2014; 15: 567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao RD, Flynn PJ, Sloan JA, et al. Efficacy of lamotrigine in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, N01C3. Cancer 2008; 112: 2802–2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loprinzi CL, Qin R, Dakhil SR, et al. Phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of intravenous calcium and magnesium to prevent oxaliplatin-induced sensory neurotoxicity (N08CB/Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 997–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavaletti G. Calcium and magnesium prophylaxis for oxaliplatin-related neurotoxicity: is it a trade-off between drug efficacy and toxicity? Oncologist 2011; 16: 1667–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khattak MA. Calcium and magnesium prophylaxis for oxaliplatin-related neurotoxicity: is it a trade-off between drug efficacy and toxicity? Oncologist 2011; 16: 1780–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrmann DN, Griffin JW, Hauer P, et al. Epidermal nerve fiber density and sural nerve morphometry in peripheral neuropathies. Neurology 1999; 53: 1634–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland NR, Crawford TO, Hauer P, et al. Small-fiber sensory neuropathies: clinical course and neuropathology of idiopathic cases. Ann Neurol 1998; 44: 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siau C, Xiao W, Bennett G. Paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies: Loss of epidermal innervation and activation of Langerhans cells. Exp Neurol 2006; 201: 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Chemotherapy-evoked neuropathic pain: abnormal spontaneous discharge in A-fiber and C-fiber primary afferent neurons and its suppression by acetyl-L-carnitine. Pain 2008; 135: 262–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flatters SJ, Bennett GJ. Studies of peripheral sensory nerves in paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Pain 2006; 122: 245–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng H, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Mitotoxicity and bortezomib-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp Neurol 2012; 238: 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Effects of mitochondrial poisons on the neuropathic pain produced by the chemotherapeutic agents, paclitaxel and oxaliplatin. Pain 2012; 153: 704–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janes K, Doyle T, Bryant L, et al. Bioenergetic deficits in peripheral nerve sensory axons during chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain resulting from peroxynitrite-mediated post-translational nitration of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Pain 2013; 154: 2432–2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghirardi O, Lo Giudice P, Pisano C, et al. Acetyl-L-Carnitine prevents and reverts experimental chronic neurotoxicity induced by oxaliplatin, without altering its antitumor properties. Anticancer Res 2005; 25: 2681–2687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen Y, Zhang ZJ, Zhu MD, et al. Exogenous induction of HO-1 alleviates vincristine-induced neuropathic pain by reducing spinal glial activation in mice. Neurobiol Dis 2015; 79: 100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji XT, Qian NS, Zhang T, et al. Spinal astrocytic activation contributes to mechanical allodynia in a rat chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain model. PLoS One 2013; 8: e60733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiguchi N, Maeda T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in spinal cord contributes to vincristine-induced mechanical allodynia in mice. Neurosci Lett 2008; 445: 140–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greeshma N, Prasanth KG, Balaji B. Tetrahydrocurcumin exerts protective effect on vincristine induced neuropathy: behavioral, biochemical, neurophysiological and histological evidence. Chem Biol Interact 2015; 238: 118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaggi AS, Singh N. Mechanisms in cancer-chemotherapeutic drugs-induced peripheral neuropathy. Toxicology 2012; 291: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scalabrino G, Peracchi M. New insights into the pathophysiology of cobalamin deficiency. Trends Mol Med 2006; 12: 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scalabrino G, Monzio-Compagnoni B, Ferioli ME, et al. Subacute combined degeneration and induction of ornithine decarboxylase in spinal cords of totally gastrectomized rats. Lab Invest 1990; 62: 297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Sahbaie P, Liang D, et al. DNA Methylation Modulates Nociceptive Sensitization after Incision. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0142046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Lin ZP, Zheng HZ, et al. Abnormal DNA methylation in the lumbar spinal cord following chronic constriction injury in rats. Neurosci Lett 2016; 610: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang PJ, Mao XH, Wang YP. Electrophysiological changes in diabetic peripheral neuropathy patients of different Chinese medicine syndrome types intervened by naoxintong and mecobalamin. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2011; 31: 1051–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izumi K, Fujise T, Inoue K, et al. Mecobalamin improved pernicious anemia in an elderly individual with Hashimoto’s disease and diabetes mellitus. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 2013; 50: 542–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCaddon A, Hudson PR. L-methylfolate, methylcobalamin, and N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive decline. CNS Spectr 2010; 15: 2–5; discussion 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang M, Han W, Zheng J, et al. Inhibition of hyperpolarization-activated cation current in medium-sized DRG neurons contributed to the antiallodynic effect of methylcobalamin in the rat of a chronic compression of the DRG. Neural Plast 2015; 2015: 197392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waikakul W, Waikakul S. Methylcobalamin as an adjuvant medication in conservative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. J Med Assoc Thai 2000; 83: 825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain 1983; 16: 109–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siau C, Bennett GJ. Dysregulation of cellular calcium homeostasis in chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 1485–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei XH, Zang Y, Wu CY, et al. Peri-sciatic administration of recombinant rat TNF-alpha induces mechanical allodynia via upregulation of TNF-alpha in dorsal root ganglia and in spinal dorsal horn: the role of NF-kappa B pathway. Exp Neurol 2007; 205: 471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, et al. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 1994; 53: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, et al. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain 1988; 32: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarthy BG, Hsieh ST, Stocks A, et al. Cutaneous innervation in sensory neuropathies: evaluation by skin biopsy. Neurology 1995; 45: 1848–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lauria G, Lombardi R, Borgna M, et al. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density in rat foot pad: neuropathologic-neurophysiologic correlation. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2005; 10: 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei XH, Yang T, Wu Q, et al. Peri-sciatic administration of recombinant rat IL-1beta induces mechanical allodynia by activation of src-family kinases in spinal microglia in rats. Exp Neurol 2012; 234: 389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin HW, Flatters SJ, Xiao WH, et al. Prevention of paclitaxel-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy by acetyl-L-carnitine: effects on axonal mitochondria, sensory nerve fiber terminal arbors, and cutaneous Langerhans cells. Exp Neurol 2008; 210: 229–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doyle T, Chen Z, Muscoli C, et al. Targeting the overproduction of peroxynitrite for the prevention and reversal of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 2012; 32: 6149–6160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li D, Huang ZZ, Ling YZ, et al. Up-regulation of CX3CL1 via nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent histone acetylation is involved in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Anesthesiology 2015; 122: 1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, et al. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB and IkappaB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends Biochem Sci 2005; 30: 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vermeulen L, De Wilde G, Notebaert S, et al. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of the nuclear factor-kappaB p65 subunit. Biochem Pharmacol 2002; 64: 963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 1994; 12: 141–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yaqub BA, Siddique A, Sulimani R. Effects of methylcobalamin on diabetic neuropathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1992; 94: 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okada K, Tanaka H, Temporin K, et al. Methylcobalamin increases Erk1/2 and Akt activities through the methylation cycle and promotes nerve regeneration in a rat sciatic nerve injury model. Exp Neurol 2010; 222: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kikuchi M, Kashii S, Honda Y, et al. Protective effects of methylcobalamin, a vitamin B12 analog, against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in retinal cell culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997; 38: 848–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akaike A, Tamura Y, Sato Y, et al. Protective effects of a vitamin B12 analog, methylcobalamin, against glutamate cytotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons. Eur J Pharmacol 1993; 241: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li G. Effect of mecobalamin on diabetic neuropathies. Beijing methycobal clinical trial collaborative group. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 1999; 38: 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morani AS, Bodhankar SL. Early co-administration of vitamin E acetate and methylcobalamin improves thermal hyperalgesia and motor nerve conduction velocity following sciatic nerve crush injury in rats. Pharmacol Rep 2010; 62: 405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasudevan D, Naik MM, Mukaddam QI. Efficacy and safety of methylcobalamin, alpha lipoic acid and pregabalin combination versus pregabalin monotherapy in improving pain and nerve conduction velocity in type 2 diabetes associated impaired peripheral neuropathic condition. [MAINTAIN]: results of a pilot study. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2014; 17: 480–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang ZB, Gan Q, Rupert RL, et al. Thiamine, pyridoxine, cyanocobalamin and their combination inhibit thermal, but not mechanical hyperalgesia in rats with primary sensory neuron injury. Pain 2005; 114: 266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devor M. Ectopic discharge in Abeta afferents as a source of neuropathic pain. Exp Brain Res 2009; 196: 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dib-Hajj SD, Cummins TR, Black JA, et al. Sodium channels in normal and pathological pain. Annu Rev Neurosci 2010; 33: 325–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bennett GJ, Liu GK, Xiao WH, et al. Terminal arbor degeneration—a novel lesion produced by the antineoplastic agent paclitaxel. Eur J Neurosci 2011; 33: 1667–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong J, Tran LT, Magun EA, et al. Production of IL-1beta by bone marrow-derived macrophages in response to chemotherapeutic drugs: synergistic effects of doxorubicin and vincristine. Cancer Biol Ther 2014; 15: 1395–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiguchi N, Maeda T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Involvement of inflammatory mediators in neuropathic pain caused by vincristine. Int Rev Neurobiol 2009; 85: 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, et al. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 2001; 19: 683–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ledeboer A, Jekich BM, Sloane EM, et al. Intrathecal interleukin-10 gene therapy attenuates paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in dorsal root ganglia in rats. Brain Behav Immun 2007; 21: 686–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elmarakby AA, Sullivan JC. Relationship between oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines in diabetic nephropathy. Cardiovasc Ther 2012; 30: 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheret C, Gervais A, Lelli A, et al. Neurotoxic activation of microglia is promoted by a nox1-dependent NADPH oxidase. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 12039–12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rubbo H, Radi R. Protein and lipid nitration: role in redox signaling and injury. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008; 1780: 1318–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Das S, Alhasson F, Dattaroy D, et al. NADPH oxidase-derived peroxynitrite drives inflammation in mice and human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via TLR4-lipid raft recruitment. Am J Pathol 2015; 185: 1944–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crampton SJ, O’Keeffe GW. NF-kappaB: emerging roles in hippocampal development and function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2013; 45: 1821–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]