Abstract

Background

Behavioral economic theories of drinking posit that the reinforcing value of engaging in activities with versus without alcohol influences drinking behavior. Measures of the reinforcement value of drugs and alcohol have been used in previous research, but little work has examined the psychometric properties of these measures.

Objectives

The present study aims to evaluate the factor structure, test-retest reliability, and concurrent validity of an alcohol-only version of the Adolescent Reinforcement Survey Schedule (ARSS-AUV).

Methods

A sample of 157 college student drinkers completed the ARSS-AUV at two time points 2–3 days apart. Test-retest reliability, hierarchical factor analysis, and correlations with other drinking measures were examined.

Results

Single, unidimensional general factors accounted for a majority of the variance in alcohol and alcohol-free reinforcement items. Residual factors emerged that typically represented alcohol or alcohol-free reinforcement while doing activities with friends, romantic or sexual partners, and family members. Individual ARSS-AUV items had fair-to-good test-retest reliability, while general and residual factors had excellent test-retest reliability. General alcohol reinforcement and alcohol reinforcement from friends and romantic partners were positively correlated with past-year alcohol consumption, heaviest drinking episode, and alcohol-related negative consequences. Alcohol-free reinforcement indices were unrelated to alcohol use or consequences.

Conclusions/Importance

The ARSS-AUV appears to demonstrate good reliability and mixed concurrent validity among college student drinkers. The instrument may provide useful information about alcohol reinforcement from various activities and people and could provide clinically-relevant information for prevention and treatment programs.

Keywords: alcohol reinforcement, college drinking, behavioral economics, psychometrics, social environment

College Students and Alcohol Use

College students have had consistently higher rates of past-month alcohol use and binge alcohol use than their non-college attending peers since the 1980s (Schulenberg & Patrick, 2012). In 2012, 60.3% of college students reported past-month alcohol use, 40.1% endorsed past-month binge drinking (five or more drinks on one occasion), and 14.4% endorsed five or more binge drinking episodes in the past month (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). In the United States, 1,825 college students die annually from unintentional alcohol-related injuries, 599,000 are unintentionally injured from drinking, and 97,000 experience alcohol-related sexual assaults (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2012).

Consequences from alcohol use extend to non-drinkers in college environments. Sixty percent of students living in residence halls or fraternities and sororities report interruptions to studying or sleeping because of others’ drinking, half report taking care of a drunken student, one-third report being insulted or humiliated by someone who was drinking, and one-fifth experience unwanted sexual advances (Wechsler, Lee, Nelson, & Kuo, 2002). In response to these figures, Healthy People 2020 identified reductions in college student binge drinking as a key national priority (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economic theories provide one framework with which to understand college drinking. These theories emphasize the reinforcing value of alcohol as compared to other available reinforcers and the tendency for individuals to maximize the utility of their actions when allocating their time (Bickel, Green, & Vuchinich, 1995).

One goal of applied behavioral economics is to determine the conditions under which alcohol use becomes the preferred behavioral choice. This is hypothesized to occur in situations where constraints on alcohol use (e.g., cost, availability) are minimized and alternate reinforcers are unavailable, unappealing, or difficult to obtain (Vuchinich & Tucker, 1988). Several studies support this theoretical model. For example, hypothetical increases in alcohol price have been associated with decreased demand, while intensity of demand (i.e., the number of drinks desired when they are free) has been associated with drinking problems in college students (Mackillop et al., 2009; Murphy, Correia, & Barnett, 2007).

The Adolescent Reinforcement Survey Schedule – Substance Use Version (ARSS-SUV) measure was adapted from the ARSS (Holmes, Sakano, Cautela, & Holmes, 1991) to quantify the relative reinforcement of using alcohol and drugs across various activities (Murphy, Correia, Colby & Vuchinich, 2005). The ARSS-SUV is a reinforcement survey that defines drug and alcohol reinforcement as the product of the frequency and enjoyment of engaging in a particular activity when drugs or alcohol are and are not used. The relative reinforcement of alcohol for each activity can then be estimated by comparing reinforcement when drugs or alcohol are used vs. when they are not used, providing a measure of relative reinforcement of using alcohol with each activity and yielding a key index in behavioral economic theories (Correia, Murphy, Irons, & Vasi, 2010). Substance-related reinforcement is positively correlated with concurrent substance-related problems and consumption (Correia, Carey, & Borsari, 2002; Correia, Simons, Carey, & Borsari, 1998; Murphy et al., 2005; Skidmore & Murphy, 2010) and predicts response to brief intervention (Murphy et al., 2005), supporting the hypothesis that the reinforcing value of drug- and alcohol-related activities provides incentives for using them. In addition, substance-free reinforcement has predicted better response to a substance-free reinforcement based intervention (Murphy et al., 2012), but has had mixed positive and negative associations with concurrent measures of substance use (Correia et al., 1998; Correia, Carey, Simons, & Borsari, 2003; Skidmore & Murphy, 2010), providing mixed support for the behavioral economics hypothesis that reinforcement from non-drinking activities should compete with substance use and lead to lower use. Behavioral economic theories posit that treatment and prevention programs may find success by making alcohol less reinforcing or available and making alcohol-free activities more reinforcing and available (e.g., Higgins et al., 2004; Murphy et al., 2012). Thus, assessing the types of activities that provide alcohol and alcohol-free reinforcement may be warranted for college students who receive interventions for alcohol or drug use, as the information from these assessments could inform specific areas of intervention. Nonetheless, behavioral economic theories suggest that the relationship between substance-related and substance-free reinforcement is not a simple one, as substance-free reinforcement can sometimes serve as a substitute for substance-related reinforcement and other times as a complement to substance-related reinforcement (Correia et al., 2010); yet little research has examined the underlying psychometric structure of these two complexly related constructs.

Although previous findings support behavioral economic theories of alcohol use, the ARSS-SUV has been used in a limited number of studies and its psychometric properties are not well understood (Correia et al., 2010). For example, the substance-specific ARSS-SUV was derived from a subset of items contained within a more general assessment of adolescent reinforcement, the ARSS (Holmes, Sakano, Cautela, & Holmes, 1991) and previous research has used the same subscales from the original measure (e.g., Murphy et al., 2005), despite the fact that the construct of substance-specific reinforcement may be quite different. In addition, previous studies using the ARSS-SUV have measured the reinforcement value of alcohol and drugs concurrently rather than measuring the reinforcement value of alcohol alone, and have found mixed associations of substance-free reinforcement with substance use.

Study Aim

The aim of the present investigation was to evaluate the psychometric properties of an alcohol-only version of the ARSS (ARSS-AUV) among college student drinkers and to measure its associations with alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. We first conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the ARSS-AUV to better understand the constructs that underlie the instrument and that differentiate domains of alcohol- and alcohol-free reinforcement. We also assessed the measure’s test-retest reliability within a short 2–3 day period in which the instrument should be relatively temporally stable (i.e., reinforcement domains are not hypothesized to be trait-like characteristics, but should be stable within a relatively short window). Finally, we explored the measure’s concurrent validity by testing associations of alcohol and alcohol-free reinforcement with other alcohol consumption measures to examine which indices were most predictive of past-year alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences.

Method

Participants

The present study is a secondary analysis of data collected from a study related to social networks and alcohol use (Hallgren, Ladd, & Greenfield, 2013). Two hundred and sixteen participants enrolled in the study, of which 157 met criteria for the present analysis and completed both time points. Eligibility criteria were minimal in order to sample a broad range of college drinkers and included being 18–25 years old and consuming at least one alcoholic beverage within the previous six months. Participants were undergraduate students at a large public university in the southwestern United States and received psychology course credit for participating. Ninety-one participants (58%) were female; the mean age was 19.9 years (SD = 1.9). The sample was primarily Hispanic (51.6%) and non-Hispanic White (38.9%).

Measures

Alcohol-related and alcohol-free reinforcement

The Adolescent Reinforcement Survey Schedule – Alcohol Use Version (ARSS-AUV), a modified version of the ARSS-SUV (Murphy et al., 2005), is a paper-and-pencil questionnaire that assesses the frequency of past-month engagement in and enjoyment derived from 45 activities related to peer interaction, dating, sexual activity, school, and family interactions. Each question about frequency of engagement and enjoyment is posed twice on a five-point scale – once to assess the frequency and enjoyment of the activity while using alcohol (alcohol-related reinforcement), and once to assess the frequency and enjoyment of the activity while not using alcohol (alcohol-free reinforcement). Response options on the frequency scale range from 0 (zero times) to 4 (more than once a day); response options on the enjoyment scale range from 0 (unpleasant or neutral) to 4 (extremely pleasant).

The total reinforcement ratio (TRR) was computed in three steps. First, the total alcohol-related reinforcement was computed as the mean of the cross product of the “frequency with alcohol” and “enjoyment with alcohol” items. Next, the amount of total alcohol-free reinforcement was computed in an identical manner for the “without alcohol” items. Finally, the TRR index was computed as total alcohol-related reinforcement divided by the sum of the total alcohol-related and alcohol-free reinforcement. The TRR is a ratio with values between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating more relative enjoyment if using alcohol while engaging in the various activities. To facilitate item-level analyses, reinforcement ratio scores for each item of the ARSS-AUV were computed in the same manner as the total TRR index. Item- and scale-level analyses were performed using relative reinforcement ratios and total alcohol-free reinforcement scores. The former type of score includes alcohol and alcohol-free reinforcement, reflecting the behavioral choice between drinking and not drinking during a particular activity; in contrast, the latter type of score reflects the overall alcohol-free reinforcement value of activities that could compete with alcohol use and limit consumption.

The ARSS-AUV was administered twice 2–3 days apart to assess test-retest reliability. Scores from the first administration were used in analyses unrelated to test-retest reliability.

Drinking quantity

The Graduated-Frequency Measure (GF; Clark & Midanik, 1982) was used to assess the number of times that participants drank at certain quantities (e.g., 1–2 drinks per occasion, 3–4 drinks per occasion, etc.) over the past 12 months. The measure provides a total index representing the estimated number of drinks consumed in the past year. The measure also provides an index of heaviest drinking within a single episode in the past year by asking participants to rate the highest number of drinks consumed on a single occasion during that period. A past-month version of the GF has been found to more accurately capture higher levels of drinking than other measures and provide drinking estimates that are not significantly different from daily diary reports (Greenfield, 2000). The measure had adequate internal reliability in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

Negative alcohol-related consequences

The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) was used to assess the frequency of negative alcohol-related consequences in the past year. The BYAACQ is an abbreviated 24-item version of the original 48-item YAACQ that has demonstrated good psychometric properties in a sample of college student drinkers (Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005). The instrument asks participants to provide yes/no responses to whether they experienced 24 negative alcohol-related consequences in the past year, and the summed number of negative alcohol-related consequences is computed. The measure had good internal reliability in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.85).

Analytic Plan

To assess the psychometric properties of the ARSS-AUV we computed descriptive statistics, conducted an exploratory factor analysis, assessed the test-retest reliability of indicators and factor scores, and tested associations of alcohol-reinforcement ratios and alcohol-free reinforcement scores with alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences.

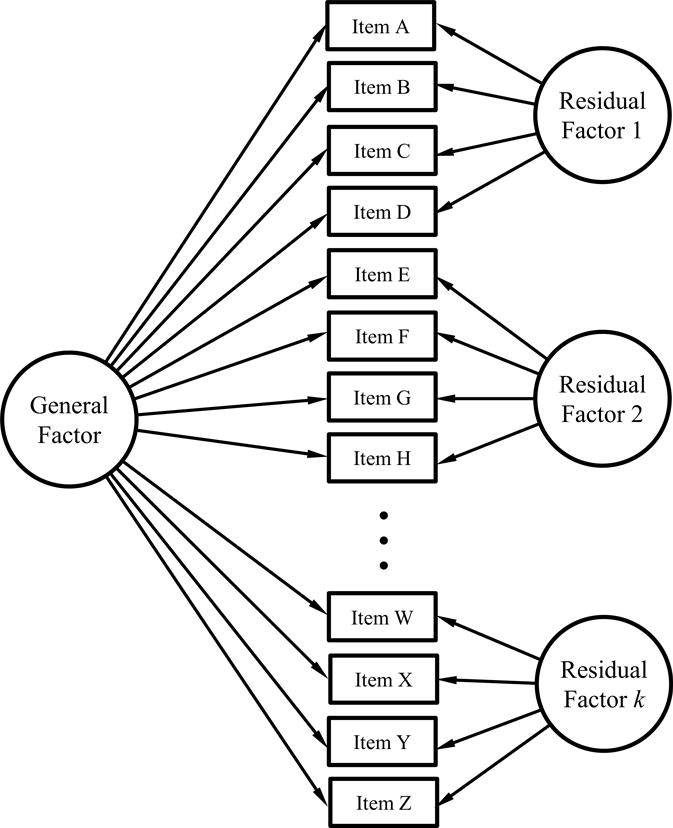

A hierarchical exploratory factor analysis was conducted that included a single general factor, which accounts for common variance across all individual items, and additional residual factors that account for the shared residual variances among sets of items (see Figure 1 for an example path diagram). This analysis assumes that a general alcohol reinforcement trait underlies the responses to all items (general factor) and that other items may also group together based on shared residual variances among subsets of items (residual factors). The factor analysis was performed using oblique rotation via the R psych package (Revelle, 2012). The number of factors was determined using parallel analysis which has been shown to more accurately identify the number of factors in exploratory factor analysis than other methods such as the rule of using the number of eigenvalues greater than 1 (Hayton, Allen, & Scarpello, 2004). The same strategy was used to examine alcohol-free reinforcement in a separate model.

Figure 1.

Prototype of hierarchical factor analysis. Residual variances and covariances between factors are not shown.

Test-retest reliability of the individual ARSS-AUV items and factors were computed using two-way, absolute-agreement, single-measures intraclass correlations (ICCs). This form of reliability assessment offers a more conservative estimate of test-retest reliability compared to other methods, such as Pearson correlation (Hallgren, 2012).

Associations between general and residual ARSS-AUV factors, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related problems were assessed by Pearson correlation tests. Alcohol reinforcement factor scores were computed using the sums of weighted scaled scores (DiStefano, Zhu, & Mîndrilă, 2009) and total alcohol-free reinforcement factor scores were computed using the means of alcohol-free reinforcement cross products. Total past-year drinking values were square-root transformed in correlation analyses to reduce positive skew. P-values for the pairwise correlations were adjusted using the sequentially rejective Bonferroni test described by Holm (1979) to reduce type-I error rates associated with multiple significance tests in correlation matrices.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Participants reported consuming a mean of 418.01 (SD = 557.03) units of alcohol over the past twelve months and a mean of 10.16 (SD = 6.62) drinks during the heaviest drinking episode in the past twelve months on the GF. Participants reported a past-year mean of 8.27 (SD = 4.86) negative alcohol-related consequences on the BYAACQ.

Mean reinforcement ratios and standard deviations of individual ARSS-AUV items are presented in Table 1. Items with mean reinforcement ratios closer to 1 indicate activities that were more reinforcing when drinking (i.e., had a greater relative reinforcement value) compared to when not drinking, such as going to parties with friends (item 16), meeting people their age (item 20), hanging out where friends meet (item 21), and flirting with, kissing, and having oral sex with dates or partners (items 5, 9, and 33). Likewise, items with mean reinforcement ratios closer to 0 indicate activities that were less reinforcing with alcohol, such as going to plays (item 40), riding a bicycle (item 41), going to work (item 42), playing a musical instrument (item 45), and exercising or playing sports (item 10).

Table 1.

ARSS-AUV Alcohol-Reinforcement Ratio Item-level Statistics

| ARSS Item no. | Item description | Reinforcement Ratio M (SD) |

Factor Loadings

|

Test-retest reliability (ICC) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Factor | RF1 | RF2 | RF3 | ||||

| 13 | places with friends | 0.30(0.23) | 0.562 | 0.616 | −0.090 | 0.100 | 0.57 |

| 21 | hang out where friends meet | 0.37(0.28) | 0.459 | 0.556 | −0.055 | −0.069 | 0.58 |

| 16 | parties with friends | 0.56(0.29) | 0.378 | 0.484 | −0.030 | −0.143 | 0.53 |

| 20 | meet people my age | 0.41(0.27) | 0.522 | 0.474 | 0.118 | −0.115 | 0.63 |

| 12 | talk with same-sex friends | 0.28(0.20) | 0.507 | 0.471 | 0.045 | 0.008 | 0.67 |

| 22 | interact with people my age and sex | 0.30(0.20) | 0.496 | 0.393 | 0.115 | 0.004 | 0.49 |

| 18 | compliments from friends | 0.27(0.24) | 0.496 | 0.387 | 0.098 | 0.055 | 0.43 |

| 11 | out to eat with friends | 0.26(0.27) | 0.446 | 0.386 | −0.019 | 0.192 | 0.48 |

| 5 | flirt with dates/partners | 0.33(0.26) | 0.516 | 0.370 | 0.186 | −0.050 | 0.55 |

| 23 | receive email/text message/letters from friends | 0.24(0.21) | 0.528 | 0.323 | 0.197 | 0.055 | 0.50 |

| 19 | ride in car with friends | 0.17(0.25) | 0.372 | 0.322 | 0.042 | 0.039 | 0.62 |

| 34 | sexual intercourse with date/partner | 0.29(0.26) | 0.485 | −0.039 | 0.597 | −0.099 | 0.79 |

| 33 | oral sex with date/partner | 0.32(0.31) | 0.483 | −0.059 | 0.557 | 0.020 | 0.76 |

| 32 | caressing date/partner | 0.31(0.24) | 0.557 | 0.042 | 0.549 | −0.017 | 0.70 |

| 9 | kiss dates/partners | 0.32(0.27) | 0.533 | 0.060 | 0.482 | 0.034 | 0.54 |

| 35 | weekends/vacation with partner | 0.23(0.27) | 0.362 | −0.091 | 0.423 | 0.106 | 0.64 |

| 8 | interact with dates/partners | 0.27(0.22) | 0.576 | 0.194 | 0.381 | 0.051 | 0.61 |

| 6 | compliments from dates/partners | 0.27(0.26) | 0.548 | 0.144 | 0.361 | 0.138 | 0.47 |

| 7 | go on dates | 0.20(0.25) | 0.424 | 0.061 | 0.341 | 0.087 | 0.55 |

| 26 | talk with siblings/family | 0.08(0.16) | 0.343 | −0.021 | 0.030 | 0.730 | 0.48 |

| 29 | talk with siblings/family about day | 0.09(0.19) | 0.278 | −0.047 | −0.009 | 0.725 | 0.57 |

| 31 | discuss school with siblings/family | 0.06(0.15) | 0.237 | −0.016 | −0.071 | 0.697 | 0.41 |

| 25 | places with siblings/family | 0.09(0.18) | 0.387 | 0.080 | −0.003 | 0.679 | 0.52 |

| 30 | weekends/vacations with siblings/family | 0.12(0.21) | 0.261 | −0.090 | 0.070 | 0.616 | 0.55 |

| 39 | read book/magazine/newspaper | 0.05(0.15) | 0.241 | −0.002 | −0.014 | 0.559 | 0.44 |

| 27 | out to eat with siblings/family | 0.08(0.19) | 0.202 | 0.022 | −0.048 | 0.493 | 0.59 |

| 28 | tell secrets to siblings/family | 0.07(0.21) | 0.407 | 0.097 | 0.095 | 0.483 | 0.59 |

| 37 | studying | 0.08(0.22) | 0.250 | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.461 | 0.71 |

| 43 | stay home/relax | 0.24(0.24) | 0.469 | 0.120 | 0.193 | 0.366 | 0.53 |

| 2 | talk with dates/partners | 0.24(0.22) | 0.539 | 0.260 | 0.248 | 0.106 | 0.61 |

| 24 | write email/text message/letter to friends | 0.21(0.21) | 0.524 | 0.292 | 0.206 | 0.094 | 0.57 |

| 3 | noticed by dates/partners | 0.28(0.24) | 0.488 | 0.269 | 0.230 | 0.014 | 0.61 |

| 15 | phone with friends | 0.15(0.23) | 0.480 | 0.309 | 0.074 | 0.234 | 0.56 |

| 17 | talk with friends about day | 0.16(0.19) | 0.470 | 0.236 | 0.190 | 0.127 | 0.51 |

| 1 | places with dates/partners | 0.26(0.26) | 0.437 | 0.132 | 0.291 | 0.068 | 0.47 |

| 4 | out to eat with dates/partners | 0.18(0.25) | 0.412 | 0.091 | 0.302 | 0.076 | 0.49 |

| 44 | go to movie | 0.14(0.25) | 0.334 | 0.001 | 0.241 | 0.226 | 0.54 |

| 38 | doing chores at home | 0.09(0.22) | 0.316 | 0.217 | −0.020 | 0.268 | 0.69 |

| 36 | going to school | 0.04(0.14) | 0.254 | 0.118 | 0.027 | 0.246 | 0.49 |

| 10 | exercise/sports | 0.04(0.17) | 0.233 | 0.087 | 0.013 | 0.294 | 0.39 |

| 42 | go to work | 0.03(0.12) | 0.208 | −0.094 | 0.222 | 0.193 | 0.66 |

| 14 | walk with friends | 0.09(0.21) | 0.179 | 0.140 | −0.051 | 0.196 | 0.42 |

| 40 | go to plays | 0.01(0.10) | 0.116 | 0.029 | 0.078 | 0.029 | 0.74 |

| 45 | play musical instrument | 0.04(0.13) | 0.104 | 0.106 | −0.134 | 0.278 | 0.71 |

| 41 | ride bicycle | 0.02(0.09) | 0.076 | 0.015 | −0.020 | 0.176 | 0.61 |

Note. Factor loadings greater than 0.316 (i.e., have at least 10% shared variance with a corresponding factor) are in bold. To facilitate easier interpretation of the factor analysis, items loading onto similar residual factors are organized together, rather than in the same order in which they occur in the ARSS-AUV. ARSS-AUV= Adolescent Reinforcement Survey Schedule – Alcohol Use Version, RF1-RF3 = residual factors, ICC = intraclass correlation.

Mean reinforcement cross-products for alcohol-free reinforcement items are presented in Table 2, with possible values ranging from 0–16. Items with higher alcohol-free reinforcement values indicate that activities were more reinforcing when not drinking, such as writing or receiving emails, text messages, or letters from friends (items 23 and 24) or talking with same-sex friends or romantic partners (items 12 and 32). Items with lower alcohol-free reinforcement included activities such as going to plays (item 40), playing musical instruments (item 45), or riding bicycles (41).

Table 2.

ARSS-AUV Alcohol-Free Reinforcement Item-level Statistics

| ARSS Item no. | Item description | Reinforcement Value M (SD) |

Factor Loadings

|

Test-retest reliability (ICC) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Factor | RF1 | RF2 | RF3 | RF4 | ||||

| 13 | places with friends | 7.54(4.48) | 0.509 | 0.633 | 0.012 | −0.063 | 0.072 | 0.69 |

| 19 | ride in car with friends | 5.69(4.29) | 0.502 | 0.569 | −0.028 | −0.042 | 0.112 | 0.63 |

| 14 | walk with friends | 3.27(3.87) | 0.312 | 0.518 | −0.032 | 0.082 | −0.100 | 0.70 |

| 17 | talk with friends about day | 7.71(4.56) | 0.538 | 0.507 | −0.003 | 0.086 | 0.114 | 0.70 |

| 18 | compliments from friends | 6.62(3.96) | 0.439 | 0.503 | 0.111 | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.28 |

| 20 | meet people my age | 4.73(3.95) | 0.444 | 0.458 | 0.083 | 0.193 | −0.025 | 0.60 |

| 21 | hang out where friends meet | 5.52(4.29) | 0.443 | 0.445 | 0.015 | −0.018 | 0.116 | 0.67 |

| 11 | out to eat with friends | 5.60(3.73) | 0.307 | 0.371 | 0.085 | 0.052 | −0.021 | 0.61 |

| 10 | exercise/sports | 7.29(4.78) | 0.191 | 0.370 | 0.004 | 0.044 | −0.103 | 0.80 |

| 12 | talk with same-sex friends | 9.85(4.74) | 0.503 | 0.368 | 0.032 | 0.143 | 0.138 | 0.75 |

| 9 | kiss dates/partners | 8.31(6.05) | 0.139 | −0.091 | 0.770 | −0.023 | −0.029 | 0.78 |

| 8 | interact with dates/partners | 9.32(5.26) | 0.321 | 0.052 | 0.724 | 0.009 | 0.042 | 0.71 |

| 2 | talk with dates/partners | 9.59(5.23) | 0.253 | −0.026 | 0.703 | −0.069 | 0.079 | 0.70 |

| 32 | caressing date/partner | 7.32(4.83) | 0.133 | −0.117 | 0.695 | 0.149 | −0.085 | 0.80 |

| 1 | places with dates/partners | 6.17(4.57) | 0.246 | 0.015 | 0.680 | −0.063 | 0.048 | 0.66 |

| 7 | go on dates | 4.31(3.26) | 0.332 | 0.161 | 0.673 | −0.010 | 0.001 | 0.64 |

| 4 | out to eat with dates/partners | 4.69(3.69) | 0.262 | 0.115 | 0.652 | −0.011 | −0.026 | 0.65 |

| 5 | flirt with dates/partners | 7.85(5.18) | 0.333 | 0.128 | 0.606 | −0.078 | 0.083 | 0.64 |

| 3 | noticed by dates/partners | 7.34(5.14) | 0.314 | 0.125 | 0.594 | −0.109 | 0.087 | 0.62 |

| 6 | compliments from dates/partners | 8.03(4.98) | 0.418 | 0.186 | 0.589 | 0.028 | 0.072 | 0.68 |

| 34 | sexual intercourse with date/partner | 4.72(4.16) | 0.039 | −0.250 | 0.569 | 0.140 | −0.037 | 0.82 |

| 35 | weekends/vacation with partner | 2.97(3.49) | 0.083 | −0.167 | 0.529 | 0.167 | −0.055 | 0.67 |

| 33 | oral sex with date/partner | 3.21(3.45) | 0.062 | −0.200 | 0.479 | 0.083 | 0.008 | 0.81 |

| 29 | talk with siblings/family about day | 6.76(4.73) | 0.460 | −0.003 | −0.004 | 0.701 | 0.074 | 0.66 |

| 26 | talk with siblings/family | 8.68(4.84) | 0.419 | −0.075 | −0.035 | 0.673 | 0.111 | 0.69 |

| 31 | discuss school with siblings/family | 5.57(4.31) | 0.409 | 0.019 | −0.018 | 0.644 | 0.044 | 0.63 |

| 25 | places with siblings/family | 5.39(3.96) | 0.459 | −0.002 | −0.009 | 0.635 | 0.110 | 0.69 |

| 27 | out to eat with siblings/family | 4.24(3.53) | 0.350 | 0.055 | 0.088 | 0.555 | −0.024 | 0.52 |

| 30 | weekends/vacations with siblings/family | 4.20(4.16) | 0.247 | 0.014 | 0.021 | 0.553 | −0.073 | 0.58 |

| 28 | tell secrets to siblings/family | 2.59(3.36) | 0.270 | 0.120 | 0.104 | 0.468 | −0.106 | 0.69 |

| 37 | studying | 5.17(4.47) | 0.397 | 0.281 | −0.064 | 0.403 | −0.011 | 0.63 |

| 36 | going to school | 7.54(4.39) | 0.472 | 0.270 | 0.037 | 0.357 | 0.062 | 0.70 |

| 24 | write email/text message/letter to friends | 10.24(4.55) | 0.705 | 0.052 | 0.054 | 0.082 | 0.582 | 0.74 |

| 23 | receive email/text message/letters from friends | 10.55(4.38) | 0.714 | 0.046 | 0.050 | 0.112 | 0.580 | 0.70 |

| 22 | interact with people my age and sex | 8.38(4.58) | 0.504 | 0.314 | 0.044 | 0.067 | 0.214 | 0.56 |

| 15 | phone with friends | 6.27(4.64) | 0.437 | 0.259 | −0.043 | 0.118 | 0.188 | 0.71 |

| 44 | go to movie | 3.15(2.01) | 0.270 | 0.158 | 0.148 | 0.135 | 0.030 | 0.47 |

| 43 | stay home/relax | 7.39(4.35) | 0.259 | 0.238 | 0.044 | 0.086 | 0.021 | 0.64 |

| 42 | go to work | 3.08(3.56) | 0.251 | 0.249 | 0.050 | 0.159 | −0.035 | 0.68 |

| 38 | doing chores at home | 3.02(3.31) | 0.237 | 0.249 | 0.124 | 0.315 | −0.154 | 0.67 |

| 16 | parties with friends | 3.10(3.15) | 0.224 | 0.231 | 0.125 | 0.069 | −0.024 | 0.52 |

| 39 | read book/magazine/newspaper | 5.01(4.30) | 0.180 | 0.251 | −0.122 | 0.247 | −0.097 | 0.67 |

| 40 | go to plays | 0.68(1.86) | 0.121 | 0.135 | 0.025 | 0.250 | −0.120 | 0.73 |

| 45 | play musical instrument | 1.46(3.43) | −0.040 | 0.072 | −0.174 | −0.106 | 0.022 | 0.92 |

| 41 | ride bicycle | 2.12(3.77) | −0.115 | 0.172 | −0.008 | 0.082 | −0.273 | 0.82 |

Note. Values could range from 0 to 16. Factor loadings greater than 0.316 (i.e., have at least 10% shared variance with a corresponding factor) are in bold. To facilitate easier interpretation of the factor analysis, items loading onto similar residual factors are organized together, rather than in the same order in which they occur in the ARSS-AUV. ARSS-AUV= Adolescent Reinforcement Survey Schedule – Alcohol Use Version, RF1-RF4 = residual factors, ICC = intraclass correlation.

Exploratory Hierarchical Factor Analyses

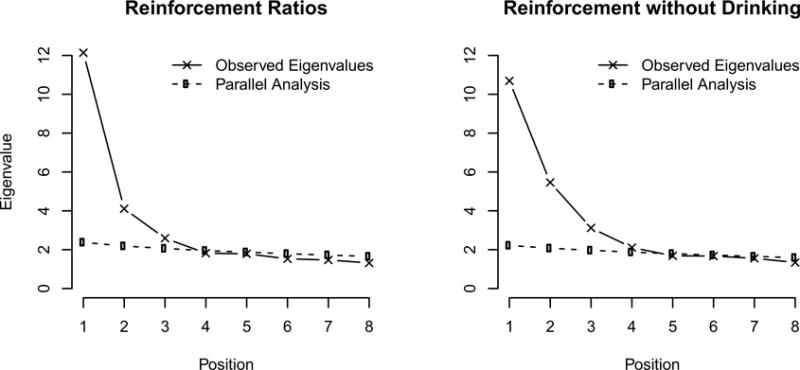

Parallel analyses indicated that three factors provided the best model fit for factor analysis of the reinforcement ratio items and that four factors provided the best model fit for the alcohol-free reinforcement items (see Figure 2). Hierarchical exploratory factor analysis results are shown in the middle columns of Table 1 (reinforcement ratios) and Table 2 (alcohol-free reinforcement). Overall fit was good for the reinforcement ratio items: χ2(df=858, N=157) = 1452.45, p < .001, root mean square residual (RMSR) = 0.06, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.076 and for the alcohol-free reinforcement items: χ2(df=816, N=157) = 1427.83, p < .001, RMSR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.079. Factor loadings greater than 0.316 are in bold font in Tables 1 and 2 and indicate that the item shared at least 10% variance with a corresponding factor.

Figure 2.

Parallel analysis results. Parallel analysis results display medians of 1000 simulated eigenvalues.

The majority of ratio and alcohol-free reinforcement items mapped onto their respective general factors (see Tables 1 and 2) above the nominal 0.316 level. Ratio items with the lowest general factor loadings (Table 1) had low means (indicating low relative reinforcement when using alcohol), and all ratio items with factor loadings less than 0.316 had means that were less than 0.10, suggesting these items with low alcohol reinforcement contributed only minimal information that could be mapped onto a general factor. Alcohol-free reinforcement items with factor loadings less than 0.316 (Table 2) typically included activities that did not specify a social group (i.e., friends, romantic partners, or family), with the exception of going to parties with friends (item 16), suggesting that these activities provided little information about the construct of alcohol-free reinforcement (e.g., perhaps because of the strong overlap between going to parties and social drinking in this sample). Ratio items had high internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.93) and the ratio general factor accounted for a majority of the scale variance (McDonald’s hierarchical ω = 0.60; Zinbarg, Revelle, Yovel, & Li, 2005). Likewise, the alcohol-free reinforcement items had high internal reliability (α = 0.92) and the general factor accounted for just under half of the scale variance (ω = 0.48).

Factor loadings for the residual factors (labeled RF in Tables 1 and 2) represent the degree to which each item mapped onto the residual factors after accounting for the general factors. Each residual factor had 8 to 13 items with residual factor loadings above the nominal 0.316 level except for the fourth factor of the alcohol-free items (discussed below), which had only two items above this level. There were no cross-loading items that loaded onto more than one residual factor above this level. Both the ratio and alcohol-free reinforcement items tended to map onto residual factors based on the nature of the relationship of the individual specified in the item description. For example, in both sets of items, activities involving friend or peer relationships, such as going places with friends (item 13), hanging out where friends meet (item 21), and riding in cars with friends (item 19), tended to load most strongly onto residual factor 1. Items involving significant others or dates, such as having sexual intercourse with a date or partner (item 34), having oral sex with a date or partner (item 33), and caressing a date or partner (item 32), tended to load most strongly onto residual factor 2. Items involving family members, such as talking with siblings and family members in general (item 26), talking with siblings or family members about my day (item 29), and discussing school with siblings or family members (item 31), tended to load onto residual factor 3. Items that did not specify other individuals occasionally loaded onto factor 3 as well, such as staying home and relaxing (item 43; ratio items only), going to school (item 36; alcohol-free items only), and studying (item 37; ratio and alcohol-free items). A fourth factor for the alcohol-free items had only two factors that reflected exchanging emails, text messages, or letters with friends, suggesting these activities were grouped differently than the other items in factor 1 that reflected in-person activities with friends. These two items also had the highest overall alcohol-free reinforcement, indicating that participants engaged in them frequently and found them highly enjoyable in the absence of alcohol. Nine ratio items and seven alcohol-free items did not load onto any of the three residual factors or the general factor above the 0.316 level.

Test-Retest Reliability

Test-retest reliability estimates for specific ARSS-AUV items are presented as ICCs in the right side of Tables 1 and 2. The mean item-level test-retest reliability was 0.57 for ratio items, range = 0.39 (item 10) to 0.79 (item 34); and the mean test-retest reliability for alcohol-free items was 0.67, range = 0.28 (item 18) to 0.92 (item 45). Test-retest reliability estimates for factor scores are presented as ICCs in the left-hand column of Table 3. Reliabilities for factor scores were higher than the individual item scores and ranged from 0.73 to 0.87 for ratio factors and ranged from 0.79 to 0.89 for alcohol-free factors, typically reflecting “excellent” reliability (Cicchetti, 1994).

Table 3.

ARSS-AUV Factor Score Test-Retest Reliability and Correlations

| Test-retest reliability (ICC) |

Correlations | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |||

| 1. | General factor – alcohol reinforcement | .86 | |||||||||||

| 2. | Factor 1 (friends) alcohol reinforcement | .87 | .92*** | ||||||||||

| 3. | Factor 2 (partner) alcohol reinforcement | .85 | .90*** | .74*** | |||||||||

| 4. | Factor 3 (family) alcohol reinforcement | .73 | .72*** | .52*** | .52*** | ||||||||

| 5. | General factor – non-drinking reinforcement | .87 | −.34** | −.34*** | −.21 | −.35*** | |||||||

| 6. | Factor 1 (friends) non- drinking reinforcement | .85 | −.29** | −.30** | −.15 | −.33** | .88*** | ||||||

| 7. | Factor 2 (partner) non- drinking reinforcement | .89 | −.32** | −.31** | −.22 | −.32** | .58*** | .27* | |||||

| 8. | Factor 3 (family) non- drinking reinforcement | .79 | −.21 | −.21 | −.15 | −.18 | .81*** | .61*** | .36*** | ||||

| 9. | Factor 4 (texting) non- drinking reinforcement | .84 | −.24 | −.25 | −.14 | −.26* | .79*** | .63*** | .37*** | .49*** | |||

| 10. | Alcohol Consumption (GF) | .49*** | .55*** | .39*** | .25* | −.23 | −.17 | −.18 | −.20 | −.19 | |||

| 11. | Alcohol-related consequences (BYAACQ) | .39*** | .42*** | .38*** | .13 | −.09 | −.07 | −.08 | −.07 | −.07 | .44*** | ||

| 12. | Maximum alcohol consumption | .31** | .32** | .29** | .13 | −.05 | −.05 | .02 | −.03 | −.09 | .44*** | .33** | |

Note. Significance tests are corrected for multiple tests via sequentially rejective Bonferroni correction (Holm, 1979). ICC = intraclass correlation, GF = Graduated Frequency measure, BYAACQ = Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Associations with Other Constructs

Correlations between the ratio and alcohol-free factor scores, alcohol consumption, and drinking-related problems are presented in Table 3. The alcohol reinforcement ratio general and residual ratio factor scores had moderate to large associations with past-year alcohol consumption (correlation range = 0.25 to 0.55, all p < .05), and somewhat lower associations with negative alcohol-related consequences (correlation range = 0.13 to 0.42, significant for all scales at p < .001 except residual factor 3 which was non-significant, p = 0.18) and the maximum number of drinks consumed on a single occasion in the past year (correlation range = 0.13 to 0.32, significant for all scales at p < .01 except residual factor 3 which was non-significant, p = 0.18).

Alcohol-free reinforcement factors had small to moderate negative associations with the alcohol reinforcement ratio factors (correlation range = −0.14 to −0.35), several of which were non-significant. None of the alcohol-free reinforcement factors were significantly correlated with past-year alcohol consumption, alcohol-related consequences, or past-year maximum drinking.

Discussion

The ARSS-AUV provides information about the relative reinforcing value (specifically reflecting the relative enjoyment and frequency of behavioral allocation) of engaging in activities with alcohol compared to without alcohol. Total reinforcement ratios using simple sums across all items have been positively associated with alcohol use (Murphy et al., 2005), and substance-free reinforcement moderated treatment response to a brief intervention after one month (Murphy et al., 2012). The present study extends these findings by further studying the test-retest reliability, factor structures, and associations with drinking and alcohol-related consequences for alcohol and alcohol-free reinforcement indices.

Factor-analytically derived indices had excellent test-retest reliability and individual items on the test had fair-to-good test-retest reliability. This suggests acceptable temporal stability over a short 2–3 day interval, which is one aspect of establishing evidence for the clinical utility of the instrument (e.g., Murphy et al., 2012). Hierarchical factor analyses indicated that 60% of the scale variance among ratio items and 48% of the scale variance among alcohol-free items was accounted for by unidimensional general factors. The alcohol reinforcement ratio factors exhibited strong evidence of concurrent validity, as higher scores on these measures were significantly associated with greater alcohol use with moderate to large correlation effect sizes and were associated with alcohol-related problems at small to moderate effect sizes. Alcohol-free reinforcement was not significantly associated with lower drinking or fewer alcohol-related consequences, despite this being suggested within the theoretical framework of behavioral economics (Correia et al., 2010). The results of the current study suggest that within the present sample, the alcohol reinforcement ratios provide reliable and valid indices of reinforcement derived from alcohol use relative to non-use, while the alcohol-free reinforcement items appear to be reliable but demonstrated limited concurrent validity in terms of alcohol use and problems despite often being negatively related to alcohol reinforcement ratios.

The results of the current study indicate that the ARSS-AUV items tended to group together based on whom activities are performed with as opposed to the nature of the activity. Subscales tended to represent either activities with friends, activities with romantic/sexual partners, activities with family, or for the alcohol-free items, emailing/texting/writing letters with friends. The subscales found in the present study were similar to three of the subscales from the original (non-substance use) ARSS, although one primary difference was that the activities with romantic partners factor in the current study included items related to sexual activity, which were separate factors in the original ARSS (Holmes et al., 1991). In addition, the original ARSS did not include a factor representing emailing/texting/writing letters, and the present study did not find evidence for an additional factor representing school activities that was included in the original ARSS. Together, these findings suggest that the social environment, particularly with whom an activity is conducted, plays an important part in alcohol reinforcement, and the social context should be further examined in future studies of drinking reinforcement and behavioral economics.

Several items failed to load onto either the general factors or the residual factors, and some items had low alcohol reinforcement ratios (e.g., going to school, exercising/playing sports, riding a bicycle) or alcohol-free reinforcement (e.g., going to plays, playing a musical instrument, riding a bicycle), suggesting these items may contribute little information about alcohol and alcohol-free reinforcement and may have little use in alcohol research contexts. However, removing these items from the ARSS-AUV may be of minimal benefit, as it would only slightly shorten the instrument and these items may provide clinically-relevant information for the smaller proportion of individuals who engage in these activities with or without alcohol.

The evidence of reliability and construct validity suggests that the ARSS-AUV scores also could provide clinically-useful information for treatment and prevention programs with college students. For example, in addition to providing an overall index of the reinforcing value of alcohol use, the ARSS-AUV could be used to identify individualized targets for increasing alcohol-free reinforcement, compensating lost reinforcement due to decreased drinking (see Murphy et al., 2007), or measuring changes in reinforcement from alcohol use in response to alcohol treatment and prevention programs. In addition, the high alcohol reinforcement ratios associated with specific activities in the present sample suggests possible aims for population-based prevention programs with college students. For example, associating with friends and sexual activity typically had high alcohol reinforcement ratios, and prevention programs may offer competing, non-drinking activities where friends can associate together or target ways to reduce risky behaviors associated with engaging in sexual activity under the influence of alcohol, such as sexual assault and unprotected sex (Lewis et al., 2014; Purdie et al., 2011).

One limitation of the present study was the cross-sectional nature of data collection, which prohibits drawing causal associations between ARSS-AUV scores and subsequent alcohol outcomes. Thus, future research is needed to further evaluate the potential causal links between alcohol reinforcement and the development and maintenance of alcohol problems. Additionally, the decision to recruit participants with any past-year drinking led to a wide range of drinking behaviors in the sample, which restricted the number of students drinking at a problematic level; however, the patterns of correlations between ARSS-AUV scores and alcohol use measures were similar to those reported here when results were analyzed among only the heaviest drinking half of the sample (results not shown). Along these lines, alcohol was assessed over a larger timeframe (i.e. past year) than sometimes seen in studies of college students; thus, the current findings may not generalize to specific periods/special events (e.g., summer vacation, spring break) and does not match the past-month time frame used by the ARSS-AUV. Other drug use was not thoroughly assessed, reducing the ability to tease apart potential overlap between reinforcement specific to alcohol use versus reinforcement from co-occurring alcohol and drug use. Although alcohol-related negative consequences were associated with alcohol reinforcement ratios in the present sample of college student drinkers, additional research should further examine the predictive power of the ARSS-AUV among samples consisting only of problematic drinkers. The current sample was predominantly Hispanic and Caucasian and consisted of only college students. Thus, results may not be generalizable to different racial or ethnic groups or non-students. Finally, a general limitation was that alcohol reinforcement measurements were limited to retrospective self-report within a circumscribed set of 45 activities. Future work may obtain more ecologically valid measures assess alcohol reinforcement, for example, via ecological momentary assessment or behavioral coding methods, and may assess reinforcement value across a wider range of activities or by using approaches that are not activity-specific (e.g., demand-curve indices).

The results of the current study suggest the ARSS-AUV provides reliable and valid measurement of alcohol-related reinforcement in college drinkers, consistent with behavioral economic theory. The lack of association between alcohol-free reinforcement and lower drinking was not entirely unexpected given the mixed associations found in previous studies (Correia et al., 2010). Although exact reasons for this lack of association cannot be determined here, it is possible that characteristics of alcohol reinforcement within the college student sample studied here contributed to this finding. For example, alcohol use in college may facilitate positive social consequences that extend beyond the drinking period, making both alcohol and alcohol-free social activities more reinforcing among students who drink more (Skidmore & Murphy, 2010), attenuating any negative associations between alcohol-free reinforcement and alcohol consumption. Alternatively, it is possible that some correlations that were non-significant but negative in magnitude (e.g., between alcohol-free reinforcement and alcohol consumption) would have been significant with a larger sample; albeit, the effect sizes for these were rather small in the present study (e.g., the highest non-significant correlation, r = −0.23 between the alcohol-free reinforcement general factor and alcohol consumption, accounted for about 5% of the variance in alcohol consumption). The ARSS-AUV items appear to break down into meaningful factors based on the social context (friends, romantic partners, or family members). This finding may be clinically relevant, as the ARSS-AUV could be utilized to identify precise sources of alcohol-specific reinforcement for targeted intervention. Future research could explore this possibility and other potential clinical uses of this measure.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIAAA grant numbers T32AA018108 and T32AA007455. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Ericka Avery, Aaron Haslam, Martin Haug, Melissa Santilli, Barbara McCrady, and Kamilla Venner for their assistance with this study.

Contributor Information

Kevin A. Hallgren, University of Washington, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Brenna L. Greenfield, University of Minnesota Medical School-Duluth, Department of Biobehavioral Health & Population Sciences

Benjamin O. Ladd, Washington State University Vancouver, Vancouver WA, Department of Psychology

References

- Bickel WK, Green L, Vuchinich RE. Behavioral economics. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1995;64:257–262. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WB, Midanik LT. Alcohol use and alcohol problems among US adults: Results of the 1979 survey. Rockville, MD: NIAAA; 1982. (Alcohol and Health Monograph No. 1). [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, Zhu M, Mîndrilă D. Understanding and using factor scores: Considerations for the applied researcher. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2009;14(20):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK. Ways of measuring drinking patterns and the difference they make: Experience with graduated frequencies. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12(1–2):33–49. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren KA. Methods for computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2012;8(1):23–34. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren KA, Ladd BO, Greenfield BL. Psychometric properties of the Important People Instrument with college student drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(3):819–825. doi: 10.1037/a0032346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayton JC, Allen DG, Scarpello V. Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods. 2004;7(2):191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Plebani-Lussier J. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance use disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:431–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GR, Sakano Y, Cautela J, Holmes GL. Comparison of factor-analyzed Adolescent Reinforcement Survey Schedule (ARSS) responses from Japanese and American adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;47:749–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(7):1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Patrick ME, Litt DM, Atkins DC, Kim T, Blayney JA, Larimer ME. Randomized controlled trial of a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention to reduce alcohol-related risky sexual behavior among college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035550. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2014-03881-001/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, Kahler CW, Ray LA, Bickel WK. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology. 2009;203(1):33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Barnett NP. Behavioral economic approaches to reduce college student drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2573–2585. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Colby SM, Vuchinich RE. Using behavioral theories of choice to predict drinking outcomes following a brief intervention. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;13(2):93–101. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. College drinking. 2012 Retrieved from < http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFactSheet.pdf>.

- Purdie MP, Norris J, Davis KD, Zawacki T, Morrison DM, George WH, Kiekel PA. The effects of acute alcohol intoxication, partner risk level, and general intention to have unprotected sex on women’s sexual decision making with a new partner. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;19(5):378–388. doi: 10.1037/a0024792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W. psych: A package for personality, psychometric, and psychological research (version 1.2.8) [software] 2012 Available from https://personality-project.org/

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG. Relations between heavy drinking, gender, and substance-free reinforcement. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18(2):158–166. doi: 10.1037/a0018513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. (NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658). [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020: Objectives. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=40.

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Kuo M. Underage college students’ drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies: Findings from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:223–236. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Tucker JA. Contributions from behavioral theories of choice to an analysis of alcohol abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):181–195. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg RE, Revelle W, Yovel I, Li W. Cronbach’s Alpha, Revelle’s Beta, McDonald’s Omega: Their relations with each and two alternative conceptualizations of reliability. Psychometrika. 2005;70:123–133. [Google Scholar]