Abstract

As clinical nanomedicine has emerged over the past two decades, phototherapeutic advancements using nanotechnology have also evolved and impacted disease management. Because of unique features attributable to the light activation process of molecules, photonanomedicine (PNM) holds significant promise as a personalized, image-guided therapeutic approach for cancer and non-cancer pathologies. The convergence of advanced photochemical therapies such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) and imaging modalities with sophisticated nanotechnologies is enabling the ongoing evolution of fundamental PNM formulations, such as Visudyne®, into progressive forward-looking platforms that integrate theranostics (therapeutics and diagnostics), molecular selectivity, the spatiotemporally controlled release of synergistic therapeutics, along with regulated, sustained drug dosing. Considering that the envisioned goal of these integrated platforms is proving to be realistic, this review will discuss how PNM has evolved over the years as a preclinical and clinical amalgamation of nanotechnology with PDT. The encouraging investigations that emphasize the potent synergy between photochemistry and nanotherapeutics, in addition to the growing realization of the value of these multi-faceted theranostic nanoplatforms, will assist in driving PNM formulations into mainstream oncological clinical practice as a necessary tool in the medical armamentarium.

Introduction - The evolution of photonanomedicine

Over the past two decades, nanotechnology has experienced a rapid diversification in its potential applications. Starting out as a pure physical and materials science study of nanoscale crystalline and composite materials, the realization that nanotechnology could spearhead new approaches to overcome hurdles in pharmaceutics and in clinical disease management, paved the way for a new era of research into medical nanotechnology: nanomedicine. In many ways, the eagerly-anticipated clinical impact of nanomedicine has been somewhat delayed by the increasing evidence that some materials, as attractive as their utility might be, exert complex effects on the body. Research into improving the clinical translatability of nanomedicines has branched into multiple new avenues of exploration, where a selection of the vast existing pool of nanomaterials are fine-tuned to improve biocompatibility, tolerance and physiological efficacy. This capacity for precise alterations of the nanomaterial composition and the respective surface properties is one of the main attractions of exploring their use as novel medicines. From a chemical standpoint, the macromolecular and supramolecular modification of nanomaterials and their precursors is evolving as a new complementary perspective to more traditional synthetic chemistry approaches for small molecule therapeutics development. The explosion in peer-reviewed publications and patents reporting novel nanomaterials proposed for specific niches within the clinic serves as a direct illustration of the collective opinion held by many researchers that nanomedicine can address multiple longstanding unmet clinical needs.

According to the European Patent Office, there are 55,830 patents filed globally to date that relate to nanoparticle technologies, in addition to the 16,908 patents filed covering liposomal technologies.1 Globally, there are a total of 209 ongoing and completed clinical trials using nanoparticles for various applications in oncology, ophthalmology, dental medicine and infectious disease, amongst numerous others.2 Of those, 82 are ongoing and only 3% have been withdrawn prior to enrollment due to funding limitations and poor patient recruitment. Moreover, there are 1,641 ongoing and completed clinical trials globally using liposomes, a clinically-accepted class of nanosized drug delivery vehicles that simultaneously encapsulate hydrophilic and lipophilic agents.3, 4 Figure 1 shows the global demographic of the five largest contributors to clinical trials of both nanoparticles and liposomes to date.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the total number of clinical trials using nanoparticles and liposomes in the five highest contributing regions of the world.5

Into this mix of innovative approaches to nanomedicine has emerged photonanomedicine (PNM), which incorporates light-activatable entities in nanomaterials with potential for exquisite spatiotemporal control. This review will discuss the progress, hurdles and prospects of PNM formulations in clinical cancer diagnostics and medicine. A specific emphasis will be placed on one of the most widely explored, photochemistry-driven process in PNM, photodynamic therapy (PDT).6, 7 PDT is based on the energy-specific activation of visible and near-infrared (NIR) absorbing molecules, photosensitizers (PSs), to generate reactive molecular species (RMS) that are phototoxic to the target disease tissues, as shown in Figure 2 (A).

Figure 2.

A) A schematic representation of the Jablonski diagram showing how PDT and fluorescence induced is by the irradiation of a PS. The PS in the ground state (S0) becomes excited by incident light (hνA or hνB) to the S1 or S2 singlet excited states. The excited PS can relax to S0 by the radiative fluorescence emission of photons (hνF), which can be used for imaging and diagnostics, or can undergo a spin forbidden process termed intersystem crossing. Through the spin flip of the excited PS, the molecule occupies a long-lived triplet excited state (T1), from which photochemical reactions occur that result in the production of cytotoxic RMS, including 1O2, that is used for PDT. B) A diagrammatic representation of the use of a PS for PDT and imaging techniques. Through type I and type II photochemical reactions, the excited sensitizer generates cytotoxic 1O2 and RMS from ground state triplet oxygen (3O2) and various biochemical substrates. The concomitant fluorescence of the PSs allows for imaging and diagnostic uses, emphasizing their inherent theranostic capacity.

The generation of various therapeutic RMS molecules proceeds through two distinct, yet interchangeable photochemical processes: type I reactions that produce radicals and radical ions, and oxygen-dependent type II reactions that produce singlet oxygen (1O2) and oxygen radicals. Both photochemical reactions are initiated from the triplet excited state of the PS; however, radiative relaxation processes of photoexcited PSs give rise to fluorescent (singlet excited to singlet ground state relaxation) and phosphorescent (triplet excited state to singlet ground state relaxation) emission of light. Owing to their fluorescent properties, PSs are inherently therapeutic and diagnostic (theranostic) agents. Figure 2 (B) is a visual representation of the theranostic nature of PS molecules, where photoexcitation results in type I and type II reactions for PDT, whilst concurrently resulting in fluorescence emission that is used for a variety of imaging and diagnostic applications. Although still largely investigational, PNM was an early player in the field of nanomedicine. Visudyne®, a non-PEGylated liposomal formulation of the PS benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD), was one of the early nanotherapeutics to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a first line treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and is considered an instrumental paradigm of photoactive nanotherapeutics and nanodiagnostics.8 Clinically, PDT is performed through the administration of a PS or its respective formulation, followed by the timely irradiation of the disease tissue using NIR light that optimally penetrates tissue in wavelength range know as the ‘optical window’ ranging between 600 nm and 1300 nm.9 The most effective PSs are those that have been tuned to maximally absorb NIR light within that optical window. Figure 3 is a graphical summary of clinical PDT and describes the different PS formulations that will be discussed in this review in addition to the functional and structural imaging modalities used in conjunction.

Figure 3.

A representation of the steps taken during a clinical PDT procedure using various PS formulations and the structural and functional information obtained using optical imaging techniques that enables treatment prediction and guidance. Following intravenous administration of the PS, an appropriate PS-light interval is required prior to irradiation using localized NIR light delivery. Through spatially confined PDT action on the tumor, the disease tissue is destroyed. Figure adapted with permission from Mallidi et al.10 Optical Imaging, Photodynamic Therapy and Optically Triggered Combination Treatments, The Cancer Journal, 21 (3), p194-205. (Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.)

The importance of the photoactivity of nanotherapeutics is not only restricted to their use in phototherapies, but also encompasses multiple parameters that distinguish such PNM formulations from the emerging pool of therapeutics. PNM formulations provide spatiotemporal control in the induction of phototherapy, spatial confinement in the phototriggered release of secondary encapsulated complementary therapeutics, temporal regulation of their respective activity and the combination of multiple theranostic agents that can be hyperspectrally and spatiotemporally resolved. This review will outline recent advancements in PNM formulations developed with respect to imaging-assisted, and rationally designed anti-cancer combination regimens. Efforts from our laboratories and others are universally driven towards achieving a unifying therapeutic and diagnostic (theranostic) nanoparticle represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

A schematic diagram of the visionary theranostic nanoconstruct that combines a fluorescence-based theranostic or imaging agent and a therapeutic drug encapsulated within. The surface is grafted with a targeting ligand to enable the molecular selectivity of the theranostic PNM formulation (1). Light activation can be used for image-guided therapy (2), photochemical generation of cytotoxic RMS for PDT of the disease tissue (4) and sequential, controlled release of synergistic agents for combinatorial cancer therapy (5).

The envisioned nanoconstruct realizes 1) the capacity to molecularly target tumors 2) the ability to mediate optical diagnostics and dosimetry 3) the selective induction of photodynamic action and 4) the spatiotemporal control of phototriggered release of synergistic anti-neoplastic agents. Progression driving technology closer to this visionary nanoconstruct will be highlighted in this review.

The fluorescence properties of PSs are highly effective for a variety of applications that distinguish them from conventional anti-cancer drugs that are formulated as nanomedicines. These include the potential for fluorescence pharmacokinetic (PK) quantitation of tumor PS concentrations,11 the fluorescence guidance of surgical tumor resection12 and the online monitoring of PDT dosimetry parameters through rates of PS photobleaching.13-15 The preclinical and clinical applications of multi-faceted theranostic PSs and the successive forward-looking PNM formulations will be discussed in greater detail in the Theranostics section.

Phototherapeutics are by no means restricted to the photochemistry-based PDT. Other noteworthy modalities exist and are emerging in clinical trials. Though not focused on in this review, photothermal therapy (PTT) plays a role in nanomedicine, such as plasmonic gold nanostructures.16, 17 There are currently two active clinical trials using plasmonic gold nanoshells, AuroShell®, for anti-cancer PTT specifically termed AuroLase® Therapy.18, 19 Requiring significantly higher power densities (W/cm2) than PDT (mW/cm2), the therapeutic response times for PTT ranging in the 10-3 – 1 s timeframe are significantly shorter than those of PDT (1 - 103 s).20 Power densities for PDT and PTT can oftentimes overlap when photothermal agents are utilized as mediators for PPT. However, considerable higher concentrations of photothermal agents are required for tissue thermalization with lower power densities, as compared to PDT. PDT is an attractive option when prolonged agent interaction times and a precise spatiotemporal controlled drug release is required. Unlike PTT, an attribute of PDT is the excellent healing process of normal tissue, thus scarring and collateral damage is minimized. The threshold nature of the PDT process also allows for the PS to be present in non-target sites as long as the overall PDT dose can be below the threshold for damage.21 This enables the illumination of larger volumes of tissue to ensure tumor margin sterilization. Ultimately, a selection of phototherapeutic strategies with distinct modes of action can be employed to address specific clinical needs.

Clinical nanomedicine

Past, present and future

The improved outcomes from many of the now-approved nanotechnology-based therapeutics have encouraged a sustained clinical effort, with several trials ongoing or recently completed. While the clinical advancements discussed here are by no means comprehensive, they will touch on some of the most recent results that highlight the varied capabilities offered by nanotechnology. A specific focus will be made on the nanomedicines requiring additional activation or triggered release, which can be selectively localized to the disease site. Figure 5 is a relatively comprehensive timeline outlining some of these liposomes, polymer and protein-based nanomedicines that have been approved by the FDA and other regional official medical regulatory bodies. The major driving force for the initial nanoformulations of the listed drugs was the improvement in their PK profiles and tolerability upon encapsulation. The developments of advanced nanomedicines to follow were motivated by a number of needs that were unmet by conventional nanoformulations. These include the need for increased control over activity and spatiotemporal drug release, the necessity for selectivity in targeted delivery of agents and the significance of multi-agent co-encapsulation. Highlights and technological advances in the global clinical progression of these multi-faceted ‘soft’ nanoplatorms will be described in this section.

Figure 5.

A timeline spanning the late 1990’s to date listing the chronological approval and clinical trial status of some lipid, polymer, and protein-based anti-cancer nanomedicines that are being leveraged to improve the PKs, safety profiles, and therapeutic indices of anti-neoplastic agents. The nanomedicines are classified under subgroups that describe the nature and primary utility of the clinical nanomedicines listed. These include nanomedicines that serve to improve drug PKs and safety profiles, to enable the controlled activation and release of therapeutics, to actively target and selectively deliver agents and those that act as a platform for multi-agent co-encapsulation. Visudyne®, which gained approval in 2000, is currently the only soft PNM formulation which enables controlled light activation. Controlled photoactivation of Visudyne® using 690 nm NIR light was approved for PDT of AMD, and Visudyne®-PDT is now showing significant promising in clinical trails for locally advanced pancreatic cancers.22

In the last quarter of a century, approximately 100 nanomedicine products have been introduced to the market for therapeutic or medical device applications.23 One of the most noticeable advancements has been in the field of oncology using soft organic nanoconstructs, such as liposomes, micelles, and polymeric and protein-based nanoparticles.24 The majority of these commercialized nanomedicine products are developed for intravenous injection, taking advantage of the size- and shape-dependent enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature for ‘passive targeting’ of solid tumors. More recently, significant clinical efforts have been made to develop targeted nanomedicine that can be activated by external stimuli, such as light, or even administered orally, which is preferred by most patients.25 Nevertheless, all these nanotechnologies have provided a solution to many hurdles in drug delivery, such as poor drug solubility and stability, suboptimal PK profiles and adverse systemic side-effects, all of which will be discussed in further detail within this review.

In the context of PNM, in 2000, the FDA approved the non-PEGylated liposomal BPD formulation, Visudyne®, for the PDT management of the wet form of AMD. To date, PDT using Visudyne® has saved the vision of millions of patients with retinal pathologies, and has been shown to work even more effectively using combination strategies.26 As discussed earlier, the liposomal PNM formulation Visudyne® pushes the boundaries of typical nanotherapeutics in that it enables the regulation of spatiotemporal control over treatment induction, and thus bears huge clinical potential with regards to the impact this regulated approach can have on combination cancer therapies.8, 27 The immediate clinical impact of Visudyne® is further evidenced in the ongoing clinical trials for pancreatic cancers.22 In our VERTPAC-01 Phase I/II trial, PDT was conducted using Visudyne® in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer.22 Laser light at 690 nm can be delivered via single or multiple fibers positioned percutaneously under computed tomography (CT) guidance for photochemical activation of Visudyne® within the tumor interstitium. At 40J, PDT consistently induced 12 mm of necrosis in the tumors with a low incidence of mild adverse events (e.g. abdominal pain and inflammation), thus meeting all endpoints of the study. In the same trial, CT scans prior to and following treatment showed a strong positive correlation between contrast-derived venous blood content and necrotic volume in the tumor.28 These results suggested that contrast CT could provide key surrogate dosimetry information to assess treatment response and will be discussed further in the Theranostics section. In an earlier clinical study on patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer, Bown et al. performed PDT using the PS meso-tetrahydroxyphenyl chlorin (mTHPC), that is reconstituted in a mixture of water and ethanol containing polyethylene glycol (PEG).29 In this study, up to six optical fibers were used to deliver light percutaneously under CT guidance for effective mTHPC- PDT, which had a 100% response rate and a median overall survival of 9.5 months. More recently, Moore et al. demonstrated that the PS WST-11, a Cremophor® emulsion of the palladium-bacteriopheophorbide TOOKAD®, can be used for ultrasonography-guided vascular-targeted PDT of low-risk prostate cancer in patients that have limited therapeutic intervention options.30 It should be noted that the delivery of light can be achieved in many ways and, in the case of pancreatic cancer discussed above, ultrasound guided endoscopes and fiber optics also provide a conduit for direct light delivery into deep situated tumors. Placement of multiple fibers is also possible for treating large tumors such as glioblastoma.22, 31 To manage tumors with poorly defined margins or those of disseminated nature, light delivery over large areas is made possible clinically with diffusing tip fibers, balloons and scattering media.32

To put the growing excitement of the emerging oncological indications of PNM formulations into perspective, the current clinical status of soft nanotechnology that are often used in the building blocks of advanced PNM formulations will be reviewed. Selective tumoral activation of nanotechnology is also being clinically evaluated with Celsion™’s ThermoDox® in the Phase III HEAT trial for hepatocellular carcinoma.33 ThermoDox® is a PEGylated liposomal formulation designed to thermally release doxorubicin upon radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Results made available from Celsion™’s press releases indicate that an extended duration of RFA may be critical to improving outcomes, leading to the initiation of a new Phase III trial, OPTIMA, for hepatocellular carcinoma.34-36 Although not part of PNM, Doxil®, a liposomal formulation of doxorubicin must be mentioned in any discussion of nanomedicine, as it was the first liposomal drug to be approved by the FDA in 1995.3 Doxil® is approved for the treatment of various cancers including AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma, recurrent OvCa and multiple myeloma.3 A major feature of Doxil® is the presence of surface PEG molecules that provide the liposomes with a stealth quality. ‘PEGylation’ protects the inner encapsulating doxorubicin from the external environment, prolongs circulation time to enhance passive tumor drug accumulation, and reduces cardiotoxicity associated with doxorubicin therapy. A more recent advancement in clinical nanomedicine is the FDA approval of Onivyde® (MM-398, nal-IRI), a liposomal formulation of irinotecan.37, 38 Approval for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer in 2015 was granted after the Phase III NAPOLI-1 study demonstrated an improved median overall survival using Onivyde® in combination with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin.37, 38 Besides adding new functionality to existing FDA-approved small molecule chemotherapeutics, liposomal nanotechnology also extends to the delivery of vaccines and of PSs for cancer treatments.39

Analogous to liposomes, polymer and protein-based nanotherapeutics have also been used to improve the PK and toxicity profiles of common potent chemotherapeutics. NKTR-102 is another nanoformulation of irirnotecan made by Nektar Therapeutics™, which consists of a polymeric nanoparticle conjugated to the drug. NKTR-102 is currently in Phase I to III trials for a variety of indications.40-43 Data from the Phase III BEACON trial with NKTR-102 thus far indicates that only breast cancer patient subgroups with brain and liver metastases show a significant overall survival benefit.44, 45 Genexol ®, a PEG-poly (lactic acid) micellar formulation of paclitaxel with a diameter of ~20-50 nm, was approved for use in South Korea in patients with metastatic breast and pancreatic cancers in 2001.46 Eligard® is a poly(DL-lactide/glycolide) (PLG) nanoparticle incorporating leuprolide acetate, which was approved in 2002 for advanced prostate cancer.47 Abraxane® is an albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticle, ~130 nm in diameter, which was approved by the FDA in 2005 for passive targeting of metastatic breast cancer and was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the same disease in 2008. Abraxane® received FDA approval for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in 2012, which was shortly followed by approval for the treatment of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas by the FDA and EMA in 2013.48

Beyond these capabilities, nanoscale complexes, such as liposomes and/or nanoparticles, can also be leveraged for the co-encapsulation of multiple therapeutic agents, which may be mechanistically desirable. These advances in nanoformulations allow the delivery of fixed-ratio drug combinations with unified PKs, along with the option for drug compartmentalization to regulate sequential release kinetics. Furthermore, the potential for cancer targeting and light-triggered drug release may further improve treatment outcomes in cancer. Co-encapsulated nanoformulations of dual agents are already showing promise in human trials. For example, liposomally co-encapsulated cytarabine and daunorubicin (CPX-351, Celator Pharmaceuticals™), recently completed testing in Phase II studies for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).49 CPX-351 showed a significantly improved response rate and overall survival from 4.2 to 6.6 months in patients with secondary AML, when compared to patients treated with the standard combination of free cytarabine and daunorubicin.50 Preclinically, our group recently develop a photoactivatable multi-compartmental nanoconstruct that contains a ‘membrane-like’ unilamellar liposomal shell for the loading of the PS BPD and a PEG-poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticle core containing an anti-angiogenic agent.51 The anti-angiogenic agent is photo-released within the tumor to synergistically reduce both local tumor burden and distant metastases of pancreatic cancer in vivo.51 Leveraging the hydrophobic and hydrophilic compartments of folate-targeted liposomes, Morton et al. effectively co-encapsulated both hydrophobic (erlotinib) and hydrophilic (doxorubicin) therapeutics to enhance A459 tumor control in vivo via the dynamic rewiring of apoptotic signaling pathways.52

Clinical advances have also been made in actively targeted, bioconjugated nanoformulations. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted immunoliposomes encapsulating doxorubicin were the earliest targeted chemotherapeutic immunoliposome in clinical trials, demonstrating potent antitumor activity in Phase I studies.53, 54 Merrimack Pharmaceuticals™ has also developed a human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) targeted doxorubicin immunoliposome, MM-302, for the treatment of breast cancer, which is currently in Phase II trials.55 BIND Therapeutics™ has also developed BIND-014, a docetaxel PEG-PLGA polymeric nanoparticle targeting prostate specific membrane antigen, which is currently in Phase II trials for prostate cancer and non-small cell lung carcinoma.56 This nanoconstruct is currently being initiated for an even broader range of indications. These examples of nanotherapeutics, amongst many others emerging for a large variety of oncological and non-oncological indications, demonstrate not only the clinical enthusiasm of nanomedicine and PNM but also pave the way for using light-activated, targeted, and combinatorial approaches that improve current drugs previously limited in their efficacy and safety.

Challenges to the clinical translation of photonanomedicine

As discussed in this review, incorporating the PDT approach with nanotechnology allows for the encapsulation of high PS payloads, improved photoactivity and appropriately-timed release and activation of therapeutic agents. As with all parenteral non-PDT nanoconstructs, understanding pharmacokinetics (PKs) of advanced nanoformulations and their respective constituents is fundamental in maximizing their therapeutic efficacy and expediting clinical translation. Each constituent exhibits individually unique PK and toxicology profiles, in addition to different metabolic and physiological clearance mechanisms. Furthermore, their cohesive behavior as an individual entity is distinctly different, as the resultant nanoformulation is essentially a new material. In vivo destabilization and degradation, therefore, results in complex multi-parametric physiological behaviors for each constituent of the nanoformulation. In addition to chemical composition, physical properties of nanoformulations govern the degree of efficacy and toxicity. For example, a 75 nm variant of Doxil®, was compared to the standard 100 nm formulation and was found to be more efficacious yet more toxic in tumor-bearing mice.57 By incorporating PS into nanoformulations, PDT using PNM formulations has its own challenges. Whilst one of the advantages that we have mentioned in the body of the manuscript is that light can act as a drug release mechanism, with that comes another challenge in the need for studying new PK parameters of the released drugs. However, despite this additional layer of complexity, preclinical evidence of the efficacy of anti-cancer PNM formulations has been very promising.

Unlike nanoformulations of small molecule therapeutics, encapsulated into a nanoconstruct, the physiological effects of advanced PNM formulations are not only restricted to the agent and the nanocarrier properties. PDT with PNM formulations involves the paired use of an administered agent or multiple agents formulated into one or more nanoconstructs, that is activated by an applied optical irradiation. Thus, the clinical approval of PNM formulations is dependent on the regulation of the PS, the secondary therapeutic agents when applicable, the nanomaterials used for their formulation and the light sources for photoactivation. As a result of complex tissue light scattering and attenuation events, NIR light penetration through vascularized soft tissue is limited to approximately 1 cm, thereby necessitating the use of secondary medical devices for the procedure, namely optical fibers.22, 58, 59 Optical fibers deliver light to deeply situated tumors, overcoming the limitation of light penetration, yet providing an additional regulatory obstacle in the approval of clinical PDT procedures. Clinically, the advances in fiber optic light conduits and image-guided approaches have empowered the applications of PDT that use an interstitial fiber placed directly within deep tumors. Placement of multiple fibers is also possible when treating large tumors, such as pancreatic tumors.22 For diffuse carcinomas with poorly defined margins, such as disseminated ovarian cancer metastases, light delivery over the large peritoneal cavity surface areas is made possible clinically with diffusing tip fibers, balloons and scattering media.60 In principle, the approval of novel PNM formulations can be expedited by the use of pre-approved and clinically approved PSs,61, 62 biocompatible nanomaterials,63, 64 targeted biologics,65, 66 light sources,62, 67 optical fibers68 and imaging modalities to guide therapy.69 Nonetheless, clinical approval of complex PNM formulations is still a big challenge because each individual formulation will become a different material and full screening becomes critical following any modification.

For the most part, downstream manufacture and quality control processes of the constituents comprising the evolving pre-clinical soft PNM formulations discussed in this review are well established in the biopharmaceutical industry. These constituents include liposomes, soft nanoparticles, photoactive nanoformulations and antibody-drug conjugates. Although amalgamations and modifications of the existing PNM formulation constituents will inevitably impact PK/pharmacodynamics (PD), toxicology and efficacy, the existing industrial infrastructure for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) scale-up synthesis of these advanced PNM formulations will facilitate and support their Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) toxicology studies and clinical trials. As mentioned in the previous section, one of the early PNM formulations to be approved in the clinic is Visudyne® and, therefore, there is much optimism for more complex constructs to enter into the clinic.

Forward-looking preclinical advances in inorganic PNM formulations, such as nanoscintillators70 and upconversion nanoparticles71 have enabled the conversion of deep-penetrating radiation, such as X-rays and NIR light, to visible wavelengths for deep-tissue PS excitation. However, these ambitious nanomaterials are hindered by the inherent toxicity of their components and dopants, such as heavy metal ions and rare-earth lanthanide ions. Before being considered for clinical human use, rigorous in vivo toxicology, chemical stability, physiological integrity and clearance studies are crucial to confirm their safety. Furthermore, there must be a clear clinical advantage of using such nanomaterials over more conventional direct visible and NIR-mediated PDT agents.

Despite the fact that PDT has been shown to induce distant antitumor immunity in various animal models, clinical PDT is primarily used to manage local tumors. Numerous preclinical studies have shown that PDT sensitizes tumors to inhibition by systemic cytotoxic therapies, thus reducing the spread of disease to other sites indirectly when used in combination.51, 72 Therefore, it is believed that PDT is best combined with systemic treatment modalities to maximize both local and distant tumor control. The combination of localized PDT and systemically cytotoxic therapies is also attractive for cancer treatment, which avoids overlapping toxicities and reduces the doses required to achieve the same therapeutic effect. Infrequent undesirable secondary reactions to PDT comprise skin burning, itching, and injection site reactions that include pain, edema, inflammation, extravasation, rashes, hemorrhage, and discoloration.22, 73 Although most adverse events reported with PDT were of short duration and easily manageable, it is often critical for patients to avoid direct sunlight for 24-48 hours after treatment, depending on the skin clearance rates of the PS and its respective formulation. In contrast to PDT, most chemotherapies and biologics are associated with significant and long-term side effects, such as neutropenia, diarrhea and hair-loss, and patients often require dose reduction or preemptive management. The genotoxicity of DNA-damaging cancer therapies like alkylating agents and radiation therapy is not observed with PDT, as the lack of nuclear localization of most PS molecules confines oxidative damage to the target perinuclear organelles. Unlike external beam radiation, PDT can also be repeated several times at the same site if needed, given that PS selectivity to the tumor is optimal. Moreover, studies have suggested that PDT-induced damage is generally more efficient in the tumor than tissue, thus reducing normal tissue toxicity, regardless of PS selectivity.29 Reasons for this are unclear, but elevated levels of reactive oxygen species scavengers in normal tissue are suggested.29, 74

It is becoming increasingly evident that conventional, uninformed PDT using free PSs may not be the most effective choice for cancer management. More sophisticated formulations, combination therapies, irradiation procedures and image-guidance needed to improve the clinical outcome of PDT will also impact the financial costs of the therapy. As with all other treatment modalities, additional pathological factors, such as completeness of response and the need for multiple rounds of therapy, can also influence the total costs. In general, a comprehensive treatment for pre-skin cancers may cost up to $3,500 USD for a series of treatments, and can often be covered by health insurance in the United States.75 Clinical applications of imaging-assisted PDT can be more precise, effective and less invasive, yet will lead to higher overall treatment costs. For example, clinical endoscopic PDT for early esophageal cancer can cost up to ~$5,000 (USD), which is somewhat higher than the costs of chemoradiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation therapy, which ranges from $1,500 to $3,700 USD. However, compared to standard esophagectomy that costs more than $25,000 USD, endoscopic PDT is considerably more cost-effective, and has a lower mortality rate with fewer major side effects.75

Theranostics

The concept of combining therapeutics with diagnostics is encompassed in the fairly well-known term, theranostics. PDT is inherently a theranostic modality as the molecules involved are both photochemically active (to achieve the therapeutic effect) and fluorescent (to achieve the diagnostic component). Because of the differences in treatment response observed between in vitro and in vivo systems and because of the high variability among patients that receive the same treatment, the ‘one size fits all’ approach for PDT is not appropriate.76 Thus, there is growing interest for developing personalized medicine and adapting the treatment in real time. This personalized medicine is a common goal of all these theranostic applications. Particular to PDT, several strategies may be employed to reach this objective: 1) individualize PDT dosimetry by monitoring PS fluorescence, 2) use the PS fluorescence properties to guide surgery, and 3) monitor the treatment efficiency by involving other imaging modalities, such as CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or photoacoustic imaging (PAI).

Optically- guided theranostics

As mentioned in the introduction, once a PS is photoexcited, it can relax either through intersystem crossing transitions eventually leading to the generation of cytotoxic RMS molecules, or by fluorescence emission that is concurrently exploited for optical imaging. Both pathways are exploited to assess PDT efficiency and perform dosimetry measurements: the singlet oxygen (1O2) generation and the photobleaching of fluorescence of the PS.

a. PS fluorescence and singlet oxygen measurements as dosimetry parameters

Both photodestruction of the PS (photobleaching) during the PDT process and the quantitation of 1O2 have been proposed as means for patient-customization of PDT dosimetry. Using in vitro experiments performed on AML5 leukemic cells undergoing PDT using 5-aminlevulinic acid (ALA), Niedre et al. demonstrated in 2003 that cell survival was directly correlated with the phosphorescence intensity of 1O2 emitted at 1270 nm.77 As a consequence, measuring the intensity of the infrared (IR) emission of 1O2 in real-time is a direct way of monitoring PDT efficiency and may even aid in predicting treatment outcomes. The 1O2 IR emission is weak and requires sophisticated imaging infrastructures; therefore, dynamic longitudinal monitoring of 1O2 generation is particularly challenging in the clinic. A more realistic method of clinically assessing the degree of 1O2 generation, and thus treatment response, is the dynamic monitoring of PS photobleaching. All PS molecules are subject to varying degrees of photobleaching directly through self-oxidation following irradiation. Jarvi et al. proposed in 2012 an in vitro comparative study investigating two dose metrics: the 1O2 emission metric, then considered as a gold-standard metric, and the metric for photobleaching of the PS.14 They demonstrated that a positive linear correlation exists between the administered 1O2 dose calculated from the phosphorescence counts of 1O2 relaxation and PS photobleaching measurements. However, they also established that the survival rate is only correlated with the degree of photobleaching as long as the oxygen partial pressure remains above 5 μM. Thus, photobleaching is not a reliable parameter for PDT under hypoxia. In 2014, Mallidi et al. published a clinical comparison between the two metrics on 26 healthy patients subjected to ALA-PDT.78 The study showed a stronger positive correlation between evolution of erythema (PDT tissue sensitization) and the PS photobleaching induced by PDT than with the 1O2 phosphorescence emission. With the evolution of better detection systems and imaging modalities, the possibility of monitoring both direct (photobleaching metrics and 1O2 phosphorescence) and indirect (structural and functional properties of the tumor) treatment prediction parameters will drive the theranostics arena towards patient personalization. Towards this goal, the following sections discuss the current developments in imaging techniques and nanotechnology geared towards personalized therapies using integrated PNM formulations.

b. Advances in imaging and spectroscopy

Outstanding progress has been made from the optical and software development perspective that allow fluorescence based optical-imaging for tumor detection, as well as video-rate intraoperative image-guided surgery.12 Reaching this level of complexity requires an improvement in fluorescent imaging modalities that face several challenges that include high tissue autofluorescence background levels and the complexity of deconvoluting chromophores with considerable spectral overlap. NIR excitation of PSs could be used for imaging, as it is less likely to induce autofluorescence, whilst narrow filters may also be employed to improve spectral separation. However, none of these solutions fully resolve the problem of PS spectral overlap with autofluorescence.79 Hyperspectral imaging has thus been introduced in an effort to overcome this hurdle in PS imaging. The principle is based on the unmixing of several spectra following the acquisition of emitted light in each pixel to resolve and identify the fluorophores contributing to the resultant combined emission profile. The systems that have been developed allow the spectral deconvolution of chromophores that are separated by just a few nanometers.80 Mansfield et al. illustrated the basis of hyperspectral imaging by successfully unmixing the spectra emitted by five quantum dots, all characterized by a different emission profile. Each distinct quantum dot was conjugated to different markers that bind to different cellular components including the mitochondria, microtubules, proliferation marker Ki-67, nucleus, and actin. The five colors were successfully unmixed and a map representing the spatial distribution of each quantum dot marker, and thus each cellular component, was compiled.

Developing cutting edge-technologies such as hyperspectral imaging leads to the improvement of fluorescence imaging techniques that can be used for several purposes including fluorescence imaging for theranostics and image-guided resection. In fact, surgery remains the primary treatment for the majority of solid tumors, which requires complete resection to ensure a positive prognosis. Although the peripheries of some tumor types are well-defined and do not require the precautionary extraction of additional seemingly healthy tissue, other diffuse tumor types, including metastases, are more difficult to differentiate from normal tissues, or reside adjacently to crucial structures. Therefore, the accurate delineation of precise tumor margins is required to achieve more complete resections. Sensitive optical imaging techniques, such as fluorescence imaging can thus guide surgery. The clinically-approved extrinsic fluorophores indocyanine green (ICG) and fluorescein sodium are examples of florescence contrast agents that have been frequently used to assist intraoperative dissection.81 More specifically, the endogenous PS protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) that accumulates in tumor tissue upon administration of the clinically-approved precursor, ALA, is currently in multiple clinical trials for assisting the resection of gliomas.82 As shown in Figure 6, the white light images and PpIX fluorescence images acquired intraoperatively from a patient with glioma are contrasted to emphasize the powerful advantage of fluorescence imaging for increasing the accurate tumor detection and boundary delineation for surgical guidance.

Figure 6.

A) Intraoperative white light image of the brain of a glioma patient with the respective fluorescence image following administration of ALA. The tumor is not visible to the naked eye, however, the endogenous PS PpIX preferentially accumulates in the tumor and enables its fluorescent detection and surgical guidance, which appears pink under blue light excitation in B) Figure reprinted from Widhalm et al. 83

The field of fluorescence-guided surgery is less well-established, as compared to other imaging modalities. However, it has recently made outstanding strides in the clinical arena, mainly to precisely delineate tumor margins and for advancing real-time NIR PSs image processing techniques during surgical procedures, as comprehensively reviewed by Elliott et al.12 During a Phase III clinical trial, image-guided tumor resection was performed following ALA administration on 322 patients with malignant glioma.84 It was observed that the resection was complete for 65% of the patients operated on under fluorescence image-guided surgery, as compared to 36% for patients operated on with white light surgery.84 Utilizing the inherent photosensitizing capacity of PSs used for fluorescence-guided resection, intraoperative PDT treatment can be used to eliminate the residual disease following surgery.32, 85 In a single-center Phase III trial on 27 glioblastoma patients, fluorescence-guided resection and post-operative PDT using a secondary administered PS doubled survival of patients, as compared to surgery performed under white light followed by radiotherapy (52.8 vs. 24.6 weeks, respectively).32 Fluorescence-guided resection is also widely investigated for bladder cancer. It has been shown in several Phase III clinical trials that PS fluorescence-guided resection is significantly more complete than following white light cystoscopy. These different results were reviewed by Jocham et al. 86

In addition to being used to guide resection, the fluorescence may also be used to diagnose or detect small nodules and metastases diffusely disseminated. For example, Zhong et al illustrated the ability to image the in vivo fluorescence signal of Visudyne® injected into the peritoneum of a mouse with disseminated micrometastases of human ovarian carcinoma (OvCa) using a high-resolution fiber optic microendoscopy modality.87 They demonstrated that this method could be quantitative and that the signal intensity is proportional to the area of the nodules disseminated throughout the peritoneal cavities, thus enabling the longitudinal fluorescence-guided monitoring of treatment response.

Some PS molecules require strategies to enhance their selectivity by directing them to biomolecules or membrane-associated enzymes that are over-expressed on tumor cells or by manipulating cancer-activated metabolism pathways.12, 81 In 2011, van Dam et al. reported the first clinical utility of targeted tumor-specific intraoperative fluorescence imaging of OvCa to improve disease staging in vivo and to maximize the extent of radical cytoreductive surgery.88 OvCa, 90-95% of which overexpress folate receptor-α, was targeted using a folate conjugate of fluorescein isothiocyanate, that could be expanded to the use of fluorescent PS conjugates. Selective theranostics using PSs have also been demonstrated preclinically using benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD) PS molecules conjugated to the anti-EGFR antibody, Cetuximab. The Cetuximab-BPD conjugates, termed photoimmunoconjugates (PICs), have been employed for the targeted imaging and PDT of non-resectable micrometastases of OvCa disseminated throughout the peritoneal cavity.11 As presented in Figure 7 (A), the PICs also enabled longitudinal fluorescence microendoscopic imaging of the remaining disseminated OvCa tumor burden following cycles of tumor-targeted activatable photoimmunotherapy (taPIT). The modality also provided robust in vivo quantitation of the imaged tumor burden (Figure 7 (B)). The details and advancements of targeted PDT using PICs and the taPIT approach will be further described in the Acquiring selectivity section.

Figure 7.

A) Images obtained by longitudinal in vivo fluorescence microendoscopy of tumor burden in a disseminated mouse model of OvCa treated with the Cet-BPD PIC without and with (taPIT) light activation (scale bar 100μm). B) Quantitative analyses of representative tumor fluorescence during the treatment. Solid lines indicate significant changes (P < 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t test). Figure adapted from Spring et al.11

Ultimately, advanced tumor-selective PNM formulations will be utilized in the same manner, where the fluorescence properties will provide the accurate delineation of tumor margins to aid surgical resection, and for the detection and photodynamic elimination of microscopic disease. Substantially prolonged circulation times of PNM formulations, as compared to free PSs or biological conjugates of PSs, will inevitably result in longer times required to attain maximal tumor-to-normal ratios. Thus, careful investigations in PKs and tumor selectivity will be critical in identifying the optimal times required to utilize the full potential of the theranostic PNM formulations.

Other imaging modalities

Theranostics also has a broader application and in this context, therapies such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy (RT), PDT or PTT can be combined with different clinical imaging techniques that include MRI, CT, positron emission tomography (PET) and NIR fluorescence.76 As a platform for the combination of therapeutic agents with imaging agents, organic carriers such as liposomes, polymers or micelles90 have been heavily investigated. In addition, inorganic nanoparticles, such as mesoporous silica nanocomposites, have also been utilized because of their biocompatibility and their high capacity for agent loading.91-93 Two types of nanodots have also been explored in the context of theranostics: quantum dots94-96 and carbon nanotubes,97 both which are utilized as photoactive nanocarriers and as visible and NIR fluorescence imaging agents. Inorganic nanoconstructs such as iron oxide nanoparticles have also be functionalized with drugs to combined MRI with a therapeutic agent.98-100 Significant interest has developed over the prospects of nanomaterials that intrinsically behave as both image contrast agents and as nanotherapeutics. One of the most prevalent examples is gold nanoparticles that, in addition to being physiologically inert, can be used as imaging agents that enhance the contrast of CT101 and surface enhance Raman spectroscopy (SERS) imaging modalities.102 Furthermore, gold nanostructures have also been shown to behave as efficacious therapeutics, such as radiosensitizers for RT,103, 104 nanoparticulate carriers of PSs for PDT105, 106 and as photothermal agents for PTT.17, 106 Gadolinium-based nanoparticles have similarly drawn such attention for their ability to improve the efficacy of RT, whilst simultaneously enhancing MRI contrast, and thus allowing for the development of MRI-guided RT theranostic nanoconstructs.107

a. Photoacoustic imaging to predict PDT efficiency

In addition to being fluorescence contrast agents, PSs are also effective photoacoustic contrast agents. PAI, a ‘light-in, sound-out’ modality provides 3D optical absorption properties of the tissue being imaged at penetration depths that are significantly deeper than fluorescence imaging. Recent work by Mallidi et al.108 and Ho et al.109 showcases the ability of PAI to monitor PS tumor uptake and directs towards the ability to personalize dosimetry based on the PS concentration at the target site. As an alternative method to assess PDT efficacy without using PS photobleaching or 1O2 luminescence, PAI can also quantify changes in blood oxygen saturation levels induced during PDT by 1O2 generation. A recent preclinical study utilized PAI to highlight the critical role of tumoral oxygen saturation levels for monitoring responsiveness to PDT.111 It was demonstrated that oxygen saturation evolution matched the tumor volume evolution and, as a consequence, was a reliable marker for PDT efficacy that could be studied non-invasively. For a PS-light-interval of 1 hour, oxygen saturation reduced to approximately 94% of the pre-PDT levels at 6 hours following treatment and increased by approximately 9% 18 hours later. In this same study, a threshold for oxygen saturation measured 6 hours and 24 hours post-PDT was established to predict tumor recurrence. Therefore, PAI could provide critical image guidance parameters when used in synchrony with PNM formulations to quantitatively monitor tumor uptake, assess the extent of the tumors response to PDT, and thus inform further cycles of therapy.

b. Computed tomography to monitor PDT

It has recently been demonstrated by preclinical and clinical studies that CT, a standard-of-care imaging method, may be used to predict the PDT dose required to treat patients with non-resectable pancreatic cancer.28 CT remains the most widely used modality to diagnose and follow the evolution of pancreatic tumors. Aside from being a reliable method to predict PDT efficiency, this protocol has the unique advantage of potentially limiting the number of procedures that patients undergo. It is an X-ray based imaging technique based on the difference of X-ray absorption coefficients of body constituents, such as bone, tissues, and vasculature. CT contrast is usually enhanced using iodine solutions, a high Z-number element that locally increase X-ray absorption.112 Elliott et al. published a preclinical study performed on rabbit orthotopic pancreatic cancer that compares several tumor controls such as blood volume, blood flow and vascular permeability surface area obtained from CT images.113 They emphasized that blood volume may be a determinant of treatment response because the lower it is, the lower the PS dose delivered. This pre-clinical study highlighted the potential of CT imaging to map the PDT dose, driven by the light attenuation in tissues. Jermyn et al. recently proposed a clinical study performed on 15 patients with locally-advanced adenocarcinoma that aimed to prove the potential of using CT imaging to predict PDT efficiency and thus adapt the treatment protocol.28 In this trial, pre-treatment and post-treatment contrast-enhanced CT scans were used. Venous blood volumes were calculated for each patient using the pre-clinical CT and then compared to the necrotic volume induced by the PDT measured using the post-treatment CT scan. The CT-derived venous blood content highly correlated with the necrotic volume normalized to the PS dose. The findings indicated that a pre-treatment CT scan may allow the prediction of the necrotic volume after PDT and, as a consequence, may inform the total PDT dose required, individualized to each patient. This clinical study corroborates the previous assumption that blood volume is a limiting factor to the effective PDT dose administered. The utility of this standard-of-care procedure could be expanded to predict patient response to PDT using parenteral PNM formulations and subsequently guide the personalization of the treatment.

c. Cerenkov emission imaging to monitor RT and PDT

Cerenkov luminescence imaging is a less common, state-of-the-art bioimaging technique currently being developed to monitor treatments such as RT, and can potentiate and guide PDT using forward-looking PNM formulations. Cerenkov imaging has recently gained substantial clinical interest with particularly strong implications in quantifying the effective dose of ionizing radiation deposited during RT.114, 115 Cerenkov optical emission spanning the UV-Visible spectrum is generated by charged particles in a dielectric medium travelling faster than the phase velocity of light in the same medium and can activate nearby PSs localized at the site of RT treatment.115, 116 Recently, the proof-of-concept of video rate Cerenkov imaging was presented, providing real time insight to the effective three-dimensional radiation dose deposited during RT, as illustrated in Figure 8.117 Although the proof-of-concept was proposed for RT of breast cancer, this dosimetry protocol may be expanded to combination treatment regimens that combine RT with PDT, providing more precise, complete and tolerable irradiation procedures. Axelsson et al. showed that Cerenkov emission is sufficient to activate the fluorescence of a PS, PpIX, although studies investigating the PDT efficacy of PSs activated using Cerenkov emission from external radiation are pending.

Figure 8.

A) The beam’s-eye-views of the applied RT fields. The blue lines refer to the multi-leaf collimator that blocks the radiation from these areas. B) The surface projection on the skin from the posterior oblique portion to be irradiated. C) Cerenkov luminescence images during RT of the posterior oblique field. The areas with the highest intensity correspond to the tissue receiving the highest effective radiation dose. Reprinted from International Journal of Radiation Oncology, 89(3), Jarvis et al.117 Cerenkov video imaging allows for the first visualization of radiation therapy in real time, 615-622. Copyright (2015), with permission from Elsevier.

β-emitting radionuclides used for PET imaging have also been known to exhibit high yields of Cerenkov emission, without the need for external activation using ionizing radiation.118 Katogiri et al. recently proposed the use of Cerenkov radiation from a β-emitting radionuclide to activate type I photochemical reactions for PDT.119 In this study, the authors reported the use of 64Cu, a radionuclide clinically used for PET imaging, to excite photocatalytic titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles through its simultaneous emission of Cerenkov radiation. This pre-clinical study demonstrated the potency of the PDT combination treatment in that tumor volumes were reduced below the detectable range when TiO2 NPs were used in combination with 64Cu. However, tumor volumes remained approximately 400 mm3 when TiO2 nanoparticles were used in conjunction with non-radioactive Cu, approximately 550 mm3 when 64Cu was used alone, and remained above 650 mm3 in the no treatment controls. Co-encapsulation of a β-emitting radionuclide with a PS in a combined novel PNM construct may promote spatiotemporally-controlled, Cerenkov-induced photodynamic activation of the PDT agent held its immediate vicinity. Furthermore, PET imaging using β-emitting radionuclides typically contrasts tumors by providing functional information, such as glucose metabolism and oxygen consumption, both critical parameters that can simultaneously monitor the extent of PDT treatment response in real time.

Although in the early stages of discovery, deep tissue PDT activation using localized Cerenkov emission provides clinically valuable advantages of either exogenous induction by ionizing radiation during RT or endogenous activation using PET probes, which can be used in concert with common clinically-accepted imaging modalities. Although PDT activation using Cerenkov radiation from β-emitting radionuclides simplifies the clinical procedure required with externally activation RT and the critical irradiation parameters associated with it, the spatial selectivity for PDT activation is entirely lost. Cerenkov-mediated PDT using an integrated PNM formulation containing a β-emitting radionuclide and a PS becomes a systemically active treatment modality, where the PK of the nanoconstruct governs induction of toxicity. Toxicity of the liver, spleen and other organs where nanoparticles tend to accumulate is likely to be observed, and therefore, tailoring size and surface properties of the PNM formulation becomes even more critical.

Additional modalities utilizing the unique inherent photoactivity of novel nanoconstructs to overcome the limited penetration of light through tissue rely on their direct interaction with deeply penetrating ionizing radiation or NIR light. Photoactive inorganic nanocrystals, such as upconverting nanoparticles71 or nanoscintillators,70, 121 respectively, are emerging as advanced deep-tissue PNM formulations, when combined with PSs to locally produce RMS at anatomical sites typically inaccessible to external photoirradiation. Because of the clinical implications of X-rays of NIR light,122 currently used for imaging and RT, these nanocrystals exhibit theranostic properties when combined with therapeutic PSs. When excited with ionizing radiation, scintillation nanoparticles emit light spanning the UV/visible/NIR spectrum and can thus internally activate associated PS with wavelengths of light typically inaccessible at such tissue depths.70 Similarly, upconverting nanoparticles absorb NIR light that penetrates tissue deeper than visible wavelengths and locally upconvert it to shorter wavelengths that efficiently excite associated PS molecules.71 Moreover, inorganic metal nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles, may elicit an inherent therapeutic effect including PTT or radiosensitization during RT, and their contrast-enhancing imaging properties can potentiate image guidance using CT. The diverse selection of nanomaterials provides a highly attractive pool of potential theranostic platforms; however, each nanomaterial can carry its own health risks and its clinical progression depends on the stringent investigations required to rule out immediate hazards or adverse health effects due to prolonged exposure. These concerns are more prominent when investigating inorganic nanomaterials composed of heavy metal atoms (noble metal nanoparticles), iron compounds (magnetic fluids), rare-earth metal compounds (up-converting and scintillating nanoparticles), inorganic oxides (silica, titania and zinc oxide nanoparticles) and transition metal composites (quantum dots). This concern is directly evident by the fact that currently, Feraheme®, a polyglucose sorbitol carboxymethylether-coated iron oxide nanoparticle formulation, is the only remaining approved inorganic nanotherapeutic following the withdrawal of four previously-approved nanoformulations.123 Although the reasons for their withdrawal were ambiguous, a warning emphasizing potential adverse immune reactions to Feraheme® was released by the FDA in 2015. As a consequence of the delay in the clinical translation of inorgnainc nanomaterials, this review will mainly focus on the advancement of nanoscale therapeutics and diagnostics composed of organic, biodegradable materials that are currently in clinical use.

Photochemistry and nanomedicine: meeting unmet clinical needs

Barriers to drug delivery

a. Tailoring nanomedicines to tumor physiology

Nanomedicine has been primarily introduced to reduce the inherent toxicity of cancer therapeutics by improving their selectivity towards tumor tissue. It is important to emphasize that as a cancer therapy, PDT is largely non-toxic in the absence of light. However, many PSs for PDT are hydrophobic, rendering their systemic administration impossible without the use of organic solvent mixtures. An example of such PSs is Foscan®, an EMA approved PDT agent (mTHPC/temoporfin) for the treatment of head and neck cancers, which is administered systemically in ethanol:propylene glycol (40:60 v/v). To reduce the need for such solvents and their associated toxicities, the application of nanoparticle encapsulation was primarily employed for PDT to render PSs compatible with physiological media, such as blood plasma. Efforts towards the nanoparticle encapsulation of photosensitizing agents have led to the development of a multitude of ‘second generation’ PSs, of which Visudyne® and Foslip®, a liposomal derivative of Foscan®, are notable examples.

An important unanticipated feature of nanoparticle encapsulation of PSs for their improved water solubility is the significantly increased selectivity for tumor tissue. For instance, Reddi et al. were among the first to explore liposomally encapsulate zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPC) and its drug delivery in vivo. Following the injection of 0.5 mg/kg-1 ZnPC in 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) liposomes, tumor tissue accumulated relatively high levels of ZnPC (0.6 μg/g), compared to <0. 1 ug/g in the muscle tissue surrounding the tumor 24 hfollowing intravenous administration.124 Given that PNM formulations can also improve the PS selectivity for tumor tissue, a variety of different types of nanocarriers have been investigated for the encapsulation of hydrophobic and hydrophilic PSs. Among the most studied are liposomes, (polymeric) micelles, and polymeric solid-lipid nanoparticles.125, 126 Many other investigators have reported that these PNM formulations also improve the tumor-to-normal ratio of PS in vivo, as summarized in Table 1.127-129

Table 1.

Drug selectivity for the target site, displayed as tumor:normal tissue ratio as a function of respective PNM formulation, type of PS, and time interval (hours post-injection).

| PNM formulation | Photosensitizer | Tumor:normal ratio | Time post-injection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| DPPC | ZnPC | 7.5* | 24 h | Reddi et al. (1987)130 |

|

| ||||

| DPPC:DPPG (9:1) | mTHPC | 1.5, 3.8, 9 * | 3 h, 6 h, 24 h | Reshetov et al. (2013)131 |

| 1.5, 1, 1 ** | ||||

|

| ||||

| DPPC:DPPG:DSPE-PEG (9:1:1) | mTHPC | 6, 10, 10 * | 3 h, 6 h, 24 h | |

| 1.5, 2.2, 2 ** | ||||

|

| ||||

| DPPC:DPPG:DSPE-PEG (9:1:1) | mTHPC | 10.8 ** | 7.3 h | Bucholz et al. (2005)132 |

|

| ||||

| (DMSO) | Hypocrellin A | 1.9, 2.6, 1.5 * | 3 h, 6 h, 24 h | Wang et al. (1999)133 |

| 1.2, 1.2, 1.5 ** | ||||

|

| ||||

| EPC | Hypocrellin A | 3.3, 3, 2.5 * | 3 h, 6 h, 24 h | |

| 2.1, 2.1, 1.1 ** | ||||

|

| ||||

| Visudyne® | BPD | 1.7, 5 #* | 3 h, 24 h | O’Hara et al. (2009)134 |

| 1.4, 3.5 #** | ||||

|

| ||||

| 1.2, 1.1 ##* | 3 h, 24 h | |||

| 1.9, 3 ##** | ||||

Single asterisks (*) indicate tumor:muscle ratio, double asterisks (**) indicate tumor:skin ratios. Hashtags refer to specific types of pancreatic tumor xenografts, where a single hashtag (#) refers to AsPC-1 pancreatic tumors and double hashtags (##) refer to PANC-1 pancreatic tumors. The PSs formulated in the studies summarized within the table are zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPC), meta-tetra (hydroxyphenyl)chlorin (mTHPC), Hypocrellin A and benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD). Ingredients of the PNM formulations include 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (DPPG), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(polyethylene glycol) (DSPE-PEG), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and egg phosphatidylchloine (EPC)

The increased propensity of nanoparticles to accumulate at the tumor site is primarily effectuated by the EPR effect. The EPR effect is the result of the high metabolic demand of the proliferating tumor mass and the resultant aberrant fenestrated angiogenic vasculature that rapidly form, in addition to poor lymphatic drainage of the tumor interstitial fluid.135 The EPR effect allows for the extravasation of high-molecular weight plasma components, and can be exploited by nanocarriers of anti-cancer drugs.136 In order for nanocarriers to fully utilize the EPR effect, a steric barrier that reduces non-specific nanoparticle-protein interactions is crucial to achieve prolonged systemic circulation times. Steric stabilization of nanocarriers with hydrophilic barrier molecules, such as PEG that grants stealth-like properties to nanocarriers can significantly reduce absorption by the liver, kidney, spleen, and the reticuloendothelial system (RES).137 Thus, PEGylation enhances the extent to which the nanoparticles extravasate at the tumor site. For PDT specifically, BPD-containing liposomes that were sterically stabilized with palmityl-D-glucoronide exhibited prolonged circulation times and increased the therapeutic efficacy of the PS, in comparison to treatment with either free BPD or non-sterically stabilized liposomal BPD.129 PNM formulations utilized for non-photochemical PTT applications have also been formulated in a similar manner using identical steric stabilization approaches. An interesting advancement in the field of thermal PNM formulations is the development of the porphysome, a self-assembled nanovesicle consisting of porphyrin-conjugated phospholipid bilayers that was pioneered by Lovell et al. and was PEGylated to improve steric stability.138 Due to the high proximity of the individual lipidated porphyrin molecules within the porphysome bilayer, the chromophores exhibited up to 1500-fold fluorescence quenching and were capable of inducing phototheramlization at levels comparable to gold nanorods. The photoacoustic effect that is concurrent with photothermalization was also leveraged for imaging using PAI. Furthermore, the unique structures were expanded to pyropheophorbide, zinc pyropheophorbide and bacteriochlorophyll porphysome variants. Doxorubicin was also encapsulated within the porphysome to yield a photothermal iteration of Doxil®.

Aside from steric stability and stealth-like properties, appropriate sizing of nanocarriers is essential for the efficacy of a nanosized drug delivery platform. Sterically stabilized liposomes smaller than 70 nm were shown to be retained by the liver,139 whereas liposomes larger than 220 nm were effectively taken up by the spleen.140 As such, it was demonstrated that PEGylated liposomes with sizes between 160-220 nm exhibited the longest circulation times in vivo.140 With respect to exploiting the EPR effect for tumor-specific delivery, the vascular fenestrations of tumor-associated vessels are approximately 100-600 nm in diameter.141 In comparison, healthy vasculature typically displays fenestrations smaller than 10 nm in diameter.142 These physiological characteristics of tumor vasculature can inform the design on nanocarriers, although many factors will influence the success of nanotherapeutics, which include tumor penetration and cellular internalization. These factors include nanoparticle size, formulation material, PEG density, geomentry and electrostatics, all of which must be independently tuned in concert for a given newly-developed PNM formulation.

b. Tailoring tumor physiology to nanomedicines using photochemistry

Given that the abnormal and leaky tumor vasculature contributes to tumor growth and disease progression, there are currently ongoing investigations geared towards the normalization of the vasculature with the aim of inhibiting disease progression.143 For instance, a recent study by Chauhan et al. reports on the normalization of the abnormal tumor vessels by blocking vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) signaling in angiogenic vascular endothelial cells.144 With respect to nanomedicine, it was shown that vessel normalization reduced the size of the vascular fenestrations and hindered the delivery of 125 nm quantum dots, whilst improving tumor penetration of 12 nm quantum dots.144 Vascular normalization is an example of how modulating the tumor physiology can enhance the homogenous intratumoral distribution and, subsequently, the therapeutic index of small molecular weight drugs and nanoparticles.145

Conversely, the expansion of tumor vascular fenestrae and vascular permeablization has been achieved by the controlled photochemical activation of a PS when confined to the intravascular space; a phenomenon reported early on by Henderson et al.146 and many others.6, 147-150 At sufficiently low PDT doses, vascular PDT (vPDT) has been shown to further enhance the EPR effect and to improve the extravasation of nanomedicines into the tumor. Low-dose vPDT using the PS BPD was specifically shown to enhance the EPR effect in an orthotropic rat prostate cancer model.147 The tumor uptake of 2,000-kDa FITC labeled dextran particles was enhanced following BPD-induced vPDT with a short 15 min PS-light interval.

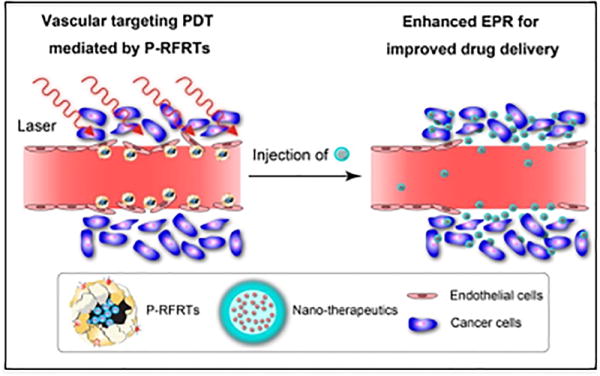

More recently, ferritin protein nanocages loaded with the ZnF16Pc PS and surface functionalized with RGD peptide were developed by Zhen et al. (Figure 9).151 These actively targeted nanoparticles, referred to as P-RFRT, selectively bound to αvβ3 integrin receptors on endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature. The irradiance was optimized to 14 mW/cm2 (50-300 mW/cm2 is used for conventional PDT) for the maximal EPR enhancement, with minimal collateral toxicity to the tumor vasculature. Following P-RFRT-mediated vPDT, enhanced tumor accumulation of varying sized cargoes, such as albumin, quantum dots and iron oxide nanoparticles, was demonstrated in multiple xenograft tumor models. Efficacy studies were carried out under the same vPDT conditions followed by administration of Doxil® in a 4T1 tumor model. Importantly, controls studies in animals treated with P-RFRT-mediated vPDT alone showed tumor growth rates similar to saline treated animals, confirming the absence of PDT-related tumor damage. In contrast, animals treated with P-RFRT-mediated vPDT followed by Doxil® treatment experienced a potent tumor-growth inhibition of 85.9%, a 75.3% improvement in efficacy over treatment with Doxil® alone.

Figure 9.

vPDT assisted EPR effect for higher tumor extravasation of nanoparticles. Proposed mechanism of action of ferritin nanoparticles loaded with ZnF16Pc PS and actively targeted with RGD-peptide (P-RFRT).151 P-RFRT mediated vPDT action first increases gaps in the tumor vasculature, thereby facilitating deeper penetration of subsequently administered therapeutic nanoparticles. Figure adapted with permission from Zhen et al.151 copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

The tumor vasculature varies considerably between different cancer types and can influence the outcome of vPDT.150 Araki et al. employed a porphyrin-based PS loaded within PEG-poly(lactic acid) nanoparticle (PN-Por), to increase vascular permeabilization, which was subsequently followed by chemotherapy using liposomal paclitaxel (PL-PTX).152 The study was performed in murine models of a colon-26 adenocarcinoma (C26) and a B16BL6 melanoma, which vary considerably in their vascular composition and permeability. In the C26 tumor model, PN-Por-mediated vPDT itself caused considerable tumor damage via endothelial cell apoptosis; however, the subsequent PL-PTX regimen did not improve outcome. Conversely, in the B16BL6 model, vPDT enhanced diffusion of PL-PTX into the tumor core and enhanced the efficacy of PL-PTX treatment. The reason for this differential vascular response between the two tumor models was associated with pericyte coverage and vessel diameter. Thus, the overall applicability of vPDT to enhance EPR based nanoparticle accumulation depends on the precise control over light dosage, a better understanding of the different innate microvasculature of tumors and on the continued development of tailored vasculature targeted nanoparticles.

An additional physical barrier in the tumor microenvironment is the stroma. The role of the tumor stroma in cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, has become increasingly regarded as a significant hindrance to drug delivery.153 It has been found that a dense avascular tumor stroma prohibits drug diffusion throughout the tumor tissue.154 In this respect, photochemical approaches may be utilized to improve the delivery and diffusion of cancer therapeutics by disrupting the rigid stromal barriers. With the use of 3D culture models, it is known that pancreatic and ovarian tumor spheroids that develop in an extracellular matrix become increasingly insensitive to chemotherapeutic agents.155 However, neoadjuvant PDT was shown to resensitize the spheroids to chemotherapy by disrupting the nodule’s three-dimensional architecture.155, 156 As such, integrating photochemistry into nanomedicines may ultimately enable the use of forward-looking PNM formulations that can enhance their own delivery into tumors using the assistance of vPDT and even throughout the stroma.

Limiting Toxicity

Even though PDT is largely non-toxic in the absence of light, there are some toxicological issues associated with the therapy. PSs that are systemically administered in free form typically accumulate at high concentrations in the liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys.157-159 The effective absorption of the PS by these organs potentially reduces the overall amount of PS that can accumulate at the tumor site, ultimately requiring higher drug concentrations to achieve the desired effect. Although the near lack of toxicity in the absence of light constitutes a major benefit of PSs in relation to other cancer therapeutics, PS accumulation in the skin has been a prominent adverse event associated with early PDT agents that lead to skin toxicity and ethical considerations regarding the quality of life of terminally ill patients.160 However, the later ‘second generation’ PSs have minimized these initial problems with skin phototoxicity. In contrast to conventional drugs, where the need for formulation has been driven by non-specific toxicity, the motivation of formulating PS is often a lack of solubility. Nanoformulations that enhance the solubility and molecular monomerization of PS in physiological environments can thus maximize their photoactivity in vivo.

With respect to PDT, several liposomal formulations containing the PS mTHPC, also known as temoporfin or Foscan®, have been developed by Biolitec Research GmbH™. These include a conventional liposomal formulation (Foslip®) and a PEGylated liposomal formulation (Fospeg®). The PDT efficacy of both formulations was superior to that of the free PS.161, 162 With respect to tumor selectivity, Fospeg® had significantly faster tumor accumulation kinetics and a higher tumor selectivity in comparison to Foslip®.163, 164 These results illustrate the significance of steric stabilization with respect to the efficiency of drug delivery and to the potential for reducing off-target phototoxicity with PS nanocarriers.

Reducing the toxicity has been employed extensively for cancer therapeutics so as to reduce the morbidity of these treatments. A fundamental paradigm for reducing toxicity using nanoparticule encapsulated drugs is Doxil®. This formulation contains high intraliposomal doses of doxorubicin, and was primarily developed to address the need for reducing the drug’s cardiac toxicity. Liposomes with high concentrations of doxorubicin, and their EPR-mediated accumulation in tumor tissue following systemic injection led to the slow release of doxorubicin at the tumor site. This nanomedicine showed an improvement in drug delivery and therapeutic efficacy, while significantly reducing the adverse toxicity.3

Photochemistry can play a unique role in providing an additional method for reducing toxicity of diagnostic and therapeutic agents by facilitating the controlled drug release from nanocarriers specifically at the site of the tumor. By using a PNM formulation co-encapsulating both photosensitizing and therapeutic agents, which preferentially accumulates at the tumor site, subsequent irradiation of the lesions results in the oxidative release of the adjuvant therapeutics from the nanocarrier. While the PNM formulation encapsulation shields the drug from systemically exerting its effects, the spatiotemporal controlled phototriggered release upon irradiation confines the toxicity of the drug to the irradiated site. This technique has been successfully applied by Spring et al., who showed that XL184 (cabozantinib, Cometriq®, a c-MET and VEGFR-2 inhibitor) entrapped in a polymeric nanoparticle, further encapsulated in photoactive lipid layers, was effective at a dose that was 1000-fold lower than the total dose of free XL184 administered. 51, 165

Limitations in cellular uptake