Summary

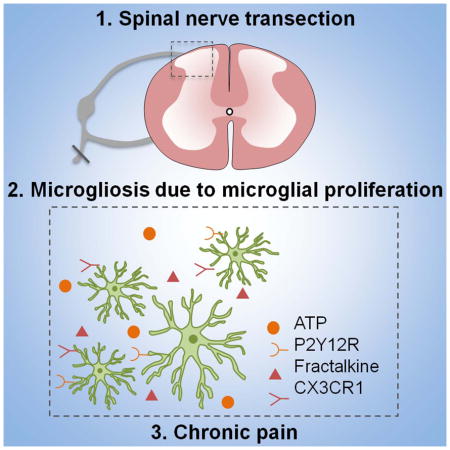

Peripheral nerve injury causes neuropathic pain accompanied by remarkable microgliosis in the spinal cord dorsal horn. However, it is still debated whether infiltrated monocytes contribute to injury-induced expansion of the microglial population. Here we found that spinal microgliosis predominantly results from local proliferation of resident microglia but not from infiltrating monocytes after spinal nerve transection (SNT), using two genetic mouse models (CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ and CX3CR1creER/+:R26tdTomato/+ mice) as well as specific staining of microglia and macrophages. Pharmacological inhibition of SNT-induced microglial proliferation correlated with attenuated neuropathic pain hypersensitivities. Microglial proliferation is partially controlled by purinergic and fractalkine signaling, as CX3CR1−/− and P2Y12−/− mice show reduced spinal microglial proliferation and neuropathic pain. These results suggest that local microglial proliferation is the sole source of spinal microgliosis, which represents a potential therapeutic target for neuropathic pain management.

Keywords: Microglia, Proliferation, Monocytes, Infiltration, Neuropathic Pain, P2Y12, CX3CR1, Mouse

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Microglia are the principal immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS) and play critical roles in the surveillance, support, protection and restoration of tissue integrity (Kettenmann et al., 2011; Ransohoff and Perry, 2009). Neuropathic pain resulting from peripheral nerve injury is associated with dramatic microgliosis in the spinal dorsal horn (Calvo and Bennett, 2012; Zhuo et al., 2011). However, the precise origin of this injury-induced expansion of the microglial population is still debated. Particularly, it is controversial whether blood-derived myeloid progenitors can contribute to the resident microglial pool under neuropathic pain conditions. For instance, several studies using bone marrow chimeras with lethally irradiated recipients favor the view that bone-marrow monocytes are able to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and differentiate into parenchymal microglia (Djukic et al., 2006; Priller et al., 2001), which is also reported after peripheral nerve injury (Echeverry et al., 2011; Sawada et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2007). In contrast, recent studies found that circulating cells do not infiltrate into the parenchyma without irradiation and transplantation (Ajami et al., 2007; Li et al., 2013), raising the possibility that circulating cells may not cross the intact BBB under pathological conditions.

Given the critical role of microgliosis in neuropathic pain (Salter and Beggs, 2014; Tsuda et al., 2005), here we re-evaluated the infiltration of bone marrow-derived monocytes in the spinal cord after spinal nerve transection (SNT). We addressed the question using two transgenic mouse lines: (1) double transgenic CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+mice in which resident CX3CR1-positive microglia are labeled with GFP while circulating CCR2-positive monocytes are labeled with RFP (Saederup et al., 2010), and (2) CX3CR1creER: R26 tdTomato reporter mice which enabled us to exclusively label resident microglia with tdTomato in the CNS (Parkhurst et al., 2013). Surprisingly, we found that SNT-induced spinal microgliosis results predominantly from local proliferation of microglia and not from infiltrated monocytes. Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of SNT-induced microglial proliferation attenuated neuropathic pain hypersensitivities. These results provide important insights on the cellular source of microgliosis after peripheral nerve injury and may inform potential therapeutic strategies for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

Results

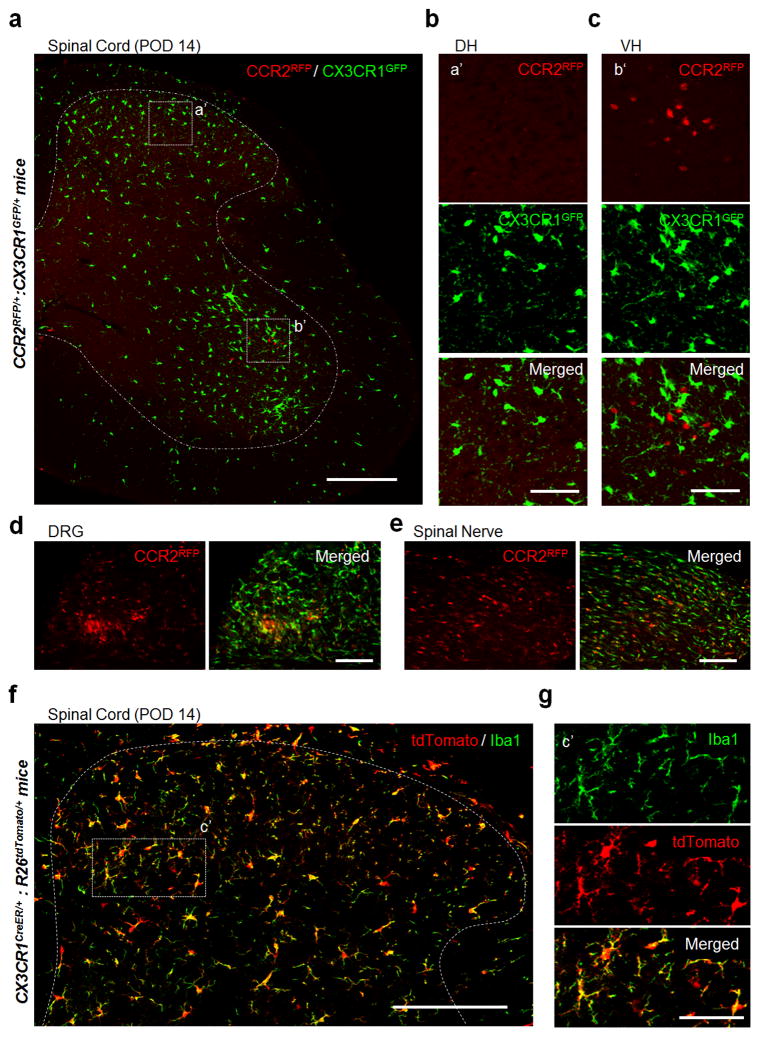

No CCR2RFP monocyte infiltration in spinal dorsal horn after SNT in CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice

To test whether microgliosis is partially due to the infiltration of blood-derived monocytes, we first took advantage of double transgenic CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice bearing GFP-labeled resident microglia and RFP-labeled monocytes (Saederup et al., 2010). In sham control mice, there were no CCR2RFP/+ cells in the spinal cord (Figures S1a) although a few patrolling CCR2RFP/+ cells were detected in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (Figure S1d). Since previous studies found blood-derived monocytes in the spinal dorsal horn after partial sciatic nerve injury (Sawada et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2007), we expected that CCR2RFP/+ monocytes would infiltrate into the dorsal horn following SNT. Surprisingly, we never observed infiltrated CCR2RFP/+ cells in the spinal dorsal horn at 3 days after SNT (POD 3, data now shown), or POD 7 or POD 14 when neuropathic pain was well established (Figures 1a–b and S1b–c). In contrast, we detected CCR2RFP/+ monocytes in the ipsilateral ventral horn of the spinal cord at POD 7 and POD 14 after SNT (Figures 1a, and 1c and S1g–i), probably due to direct injuries of ventral horn motor neurons. CCR2RFP/+ monocytes were also found in the ipsilateral DRG as well as in the damaged nerve stump (Figures 1d–e and S1d–e). Taking an alternative complementary approach to investigate CCR2 monocyte infiltration in the spinal cord, we monitored CCR2 mRNA by qRT-PCR in sham mice and at POD 7 following SNT. We found that mRNA transcript for CCR2 increased significantly to 5.57 ± 1.03 fold (P = 0.02) in the ipsilateral ventral horn at POD 7 (n = 5) from 1.19 ± 0.32 in sham mice (n = 4) or 1.58 ± 0.61 in the ipsilateral dorsal horn (n = 5) (Figure S1j). Therefore, these results confirm that CCR2-expressing cells are increased in the ipsilateral ventral but not dorsal horn at POD 7 after SNT. Finally, to determine whether CCR2RFP/+ monocytes have the ability to enter the spinal dorsal horn, we used a well-established mouse contusion model of spinal cord injury (SCI) (Wang et al., 2015) in CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice. Indeed, we found numerous CCR2RFP/+ monocytes in spinal dorsal horn 7 days after SCI (Figure S2a). Together, we demonstrate that blood-derived CCR2RFP/+ monocytes did not infiltrate into the spinal dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury.

Figure 1. No monocyte infiltration into the dorsal horn of spinal cord after spinal nerve transection.

(a–c) Representative confocal images of the ipsilateral spinal cord at post-operative day (POD) 14 following spinal nerve transection (SNT) in double transgenic CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice (a). Resident GFP+ microglia (CX3CR1GFP/+) are shown in green and infiltrated RFP+ monocytes (CCR2RFP/+) are shown in red. Dotted boxes show regions of higher magnification in the dorsal horn (DH, b) and ventral horn (VH, c), respectively. Note the obvious appearance of CCR2RFP/+ cells in the ipsilateral VH (c), but not DH (b). Scale bar is 200 μm (a) and 50 μm (b, c), respectively. Representative images of CCR2RFP cell infiltration in DH and VH before SNT and at POD7 after SNT are shown in Figures S1a–c and S1f–h. (d–e) CCR2RFP cell infiltration was found in L4 dorsal root ganglia (DRG, d) and the damaged spinal nerve stump (e) at POD 14 following SNT in CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice. Scale bar is 100 μm. Representative images of CCR2RFP cell infiltration into DRG before SNT and at POD7 after SNT are shown in Figure S1d–e. (f–g) Representative images of the spinal cord DH at POD 14 following SNT in CX3CR1creER/+: R26tdTomato/+ reporter mice (f). The dotted box indicates the region that is magnified in g. Resident microglia are tdTomato+Iba1+ cells and hematogenous monocytes are tdTomato−Iba1+ cells. There are no tdTomato−Iba1+ cells in the DH. Scale bar is 150 μm (f) and 50 μm (g), respectively. (n=4 mice per group) Representative images before SNT and at POD3, POD7 following SNT using CX3CR1creER/+: R26tdTomato/+ reporter mice are shown in Figure S3.

No CX3CR1+ monocyte infiltration after SNT in CX3CR1creER/+: R26tdTomato/+ reporter mice

Although CCR2RFP/+ monocytes did not appear in the dorsal horn after SNT, we cannot exclude the possibility that CX3CR1+ monocytes are able to infiltrate in response to peripheral nerve injury. To circumvent the issue, we used the recently established CX3CR1creER/+: R26tdTomato/+ reporter mice in which resident microglia can be exclusively labeled with tdTomato in the CNS (Parkhurst et al., 2013). This is because resident microglia show a much slower turnover while blood-derived CX3CR1+ cells are quickly replenished (Parkhurst et al., 2013). We applied tamoxifen (i.p. 150 mg/kg in corn oil, 4 doses with 2 day intervals) to CX3CR1creER/+: R26tdTomato/+ mice and allowed a 4-week interval for peripheral turnover before SNT surgery (Figure S3a). As expected, while CD11b+ CX3CR1+ monocytes were largely tdTomato negative (Figure S3b–c), CNS resident microglia express tdTomato in sham control CX3CR1creER/+: R26tdTomato/+ mice (Figure S3d). If there is monocyte infiltration after SNT, we should be able to detect a population of Iba1+ tdTomato− cells. However, we found no Iba1+ tdTomato− monocytes in the dorsal horn at POD 3, 7 and 14 after SNT (Figures 1f–g and S3e–g) although these cells were present in the ipsilateral DRG as well as in the damaged nerve stump and ipsilateral ventral horn (data not shown). In addition, Iba1+ tdTomato− monocytes were found in the spinal cord at 7 days after SCI (Figure S2b). These results indicate that there is no infiltration of hematogenous CX3CR1+ monocytes in the spinal dorsal horn after SNT.

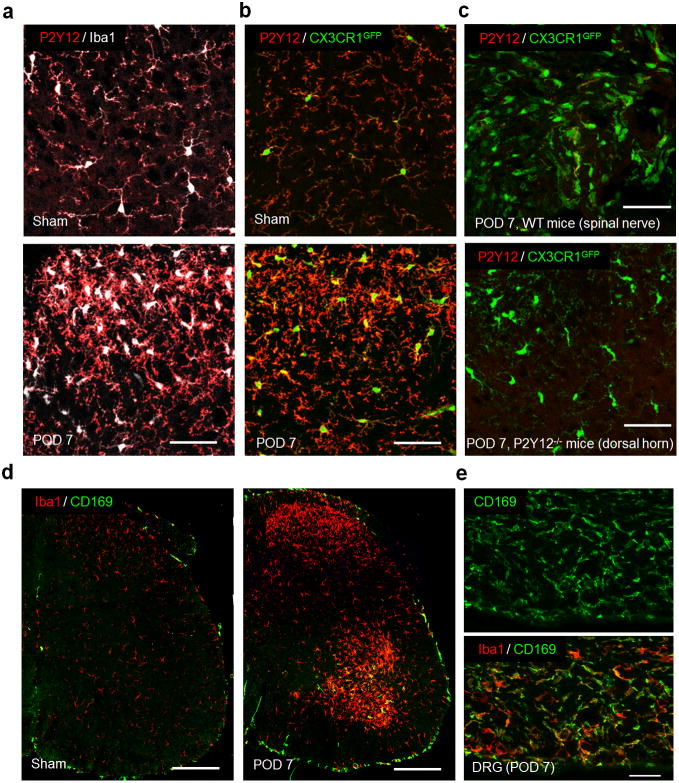

No monocytes infiltration after SNT revealed by P2Y12 and CD169 immunostaining

To circumvent genetic manipulations, we first used wild-type (WT) mice with immunostaining of P2Y12, a purinergic receptor specific for resident microglia but not for monocytes or macrophages (Butovsky et al., 2014), together with the immunostaining of Iba1 that labels both resident microglia and infiltrated monocytes. In sham control WT mice, we found all Iba1+ cells had positive P2Y12 staining in the spinal cord (Figure 2a). We expected to observe Iba1+/P2Y12− cells in the dorsal horn if monocyte infiltration occurred after SNT. However, we found no Iba1+/P2Y12− cells in the ipsilateral spinal dorsal horn at POD 7 (Figure 2a) and POD 14 (data not shown) after SNT. In addition to P2Y12 and Iba1 immunostaining in WT mice, we also performed P2Y12 staining in CX3CR1GFP/+ mice. Consistently, we did not find GFP+/P2Y12− cells in spinal dorsal horn at POD 7 days after SNT (Figure 2b). We also did not observe any P2Y12+ cells in the damaged nerve stump at POD 7 after SNT in CX3CR1GFP/+ mice consistent with microglial specific expression of P2Y12 (Figure 2c). Next, we studied monocyte infiltration after SNT by performing immunohistochemistry for CD169, a well-known marker for macrophages (Gao et al., 2015) in WT mice. We found that while the sham control spinal cord lacked CD169+ cells, the ipsilateral ventral horn exhibited CD169+ cells whereas the ipsilateral dorsal horn showed no such infiltration at POD 7 after SNT (Figure 2d). As a positive control, we confirmed the presence of CD169+ macrophages in the L4 DRG at POD 7 after SNT (Figure 2e). Taken together, by using mice with CCR2RFP-labelled monocytes, resident microglial tdTomato reporter, microglia specific cell marker (P2Y12), and macrophage specific marker (CD169), we have demonstrated that there is no infiltration of peripheral hematogenous monocytes into the spinal cord dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury. These results collectively indicate that spinal microgliosis after SNT is not due to the monocyte infiltration in contrast to previous studies (Echeverry et al., 2011; Sawada et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2007).

Figure 2. No monocyte infiltration in the spinal dorsal horn by P2Y12 and CD169 immunostaining.

(a) Representative confocal images of double immunostaining showing co-localization of P2Y12 (red) and Iba1 (white) signals in the spinal cord dorsal horn in sham and POD 7 following SNT in WT mice (n=4 per group). Scale bar is 50 μm. (b) Representative confocal images of P2Y12 staining in the spinal dorsal horn showing CX3CR1GFP positive (green) microglia are also P2Y12+ (red) in sham and POD 7 after SNT in CX3CR1GFP/+ mice (n=4 per group). Scale bar is 50 μm. (c) No P2Y12+ cells were found in the damaged nerve stump in CX3CR1GFP/+ mice and no P2Y12 immunostaining was found in the spinal dorsal horn of P2Y12−/− mice at POD 7 after SNT (n=4 per group). Scale bar is 50 μm. (d) Representative confocal images of double immunostaining showing co-localization of CD169 (green) and Iba1 (red) signals in the ipsilateral spinal cord at POD 7 in WT mice (n=2–3 mice per group). Scale bar is 100 μm. Note the obvious appearance of CD169+ cells (green) in the ipsilateral VH, but not DH. (e) CD169+ cell infiltration was also found in L4 dorsal root ganglia (DRG) at POD 7 in WT mice (n = 2–3 mice per group). Scale bar is 50 μm.

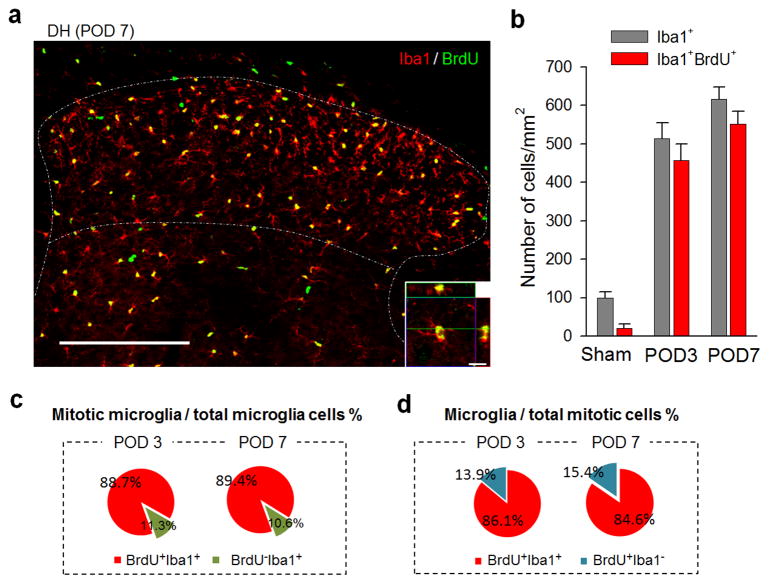

Local proliferation of resident microglia dominates spinal microgliosis after SNT

Next, we examined the contribution of microglial proliferation to SNT-induced spinal microgliosis. To this end, we first measured the incorporation of thymidine analog 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU, i.p. 100mg/kg, 2 pulses/day for 3 or 7 days) in Iba1+ microglia in spinal dorsal horn after SNT. We found the number of BrdU+ Iba1+ microglia (includes actively proliferating and recently post-mitotic cells) in ipsilateral dorsal horn at POD 3 and 7 after SNT was dramatically increased compared to that on the contralateral side or sham control mice (Figures 3a–b and S4a–c). The percentage of BrdU+ Iba1+ cells (mitotic microglia) of the total Iba1+ microglial cell population consistently reached up to ~90% after SNT (88.8±1.1% at POD 3 and 89.4±1.2% at POD 7, Figure 3c). In addition, BrdU+ Iba1+ cells dominated the BrdU+ mitotic cell population (86.1±2.8% at POD 3 and 84.6±1.4% at POD 7, Figure 3d), while there was a small percentage of BrdU+/NG2+ oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (Figures S4d and S4g) and BrdU+/GFAP+ astrocytes (Figures S4e and S4g), but no BrdU+/NeuN+ neurons (Figure S4f). These results indicate that microglial proliferation accounted for most of the proliferating events after SNT. Therefore, local microglial proliferation provides a sustainable source for microgliosis after peripheral nerve injury.

Figure 3. Local microglial proliferation dominates spinal microgliosis after spinal nerve transection.

(a) Representative confocal images of spinal cord DH showing co-localization of BrdU (green) and Iba1 (red) at POD 7 following SNT. BrdU (i.p. 100mg/kg) was applied immediately after SNT at 2 pulses/day for 7 days (n=4–6 mice per time point). Inset is z-sectioned image with high magnification, showing that BrdU+ signal are located in the nuclei of Iba1+ microglia. Scale bar is 200 μm and 10 μm for lower and higher magnification images, respectively. Representative images of the co-localization at POD3 after SNT are shown in Figure S4a. (b) Quantitative summary of the number of BrdU+ Iba1+ microglia in the ipsilateral DH (lamina I–IV) at POD3 and 7 was dramatically increased after SNT (see also Figure S4a–b for comparison of BrdU+ cells between contralateral and ipsilateral DH). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Shown is summarized data for the number of Iba1+ and Iba1+BrdU+ cell per mm2 in DH in sham control and at POD3 and 7 after surgery (n = 4–6 mice per time point). (c–d) Microglial proliferation accounted for a majority of proliferating events after SNT. Shown is the percentage of BrdU+ Iba1+ cells among total Iba1+ cells, i.e mitotic microglial cells in total microglia (c), or the percentage of BrdU+ Iba1+ cells in BrdU+ cells, i.e. microglia in total mitotic cells (d) at POD 3 and 7 after SNT (n = 4 mice at POD3 and 6 mice at POD7).

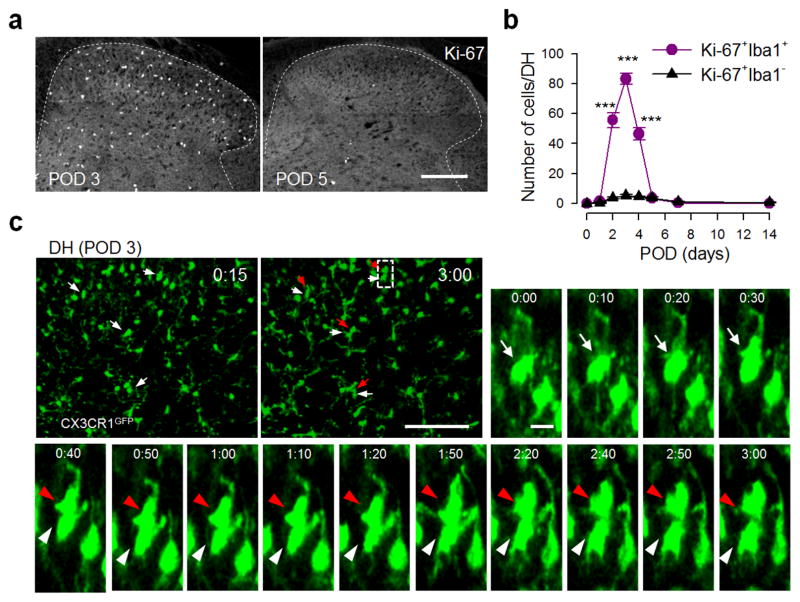

The dynamics of microglial proliferation after SNT

To study the dynamics of spinal microglia proliferation, we performed immunostaining for Ki-67 [a nuclear protein expressed in all phases of the cell cycle except the resting phase (Taupin, 2007)] to gain a snapshot of dividing microglia at different time points after SNT. We found a marked increase in Ki-67+Iba1+ microglia that started at POD 2, peaked at POD 3 and then returned to pre-injury levels later at POD 5–7 after SNT (Figure 4a–b). Specifically, the majority of Iba1+ microglial cells are proliferating microglia (Ki-67+ Iba1+ cells) at POD 3 after SNT (89.9±1.4%, Figure S5a–b). To directly monitor local proliferation, we performed time-lapse two-photon imaging of microglia in acute spinal cord slices from CX3CR1GFP/+ mice. Indeed, we found that 10.6% of microglial cells divided within a 3 hour imaging time window at POD 3 after SNT (15 of 141 microglia from 4 mice; Figure 4c and Movie S1). Together, these results provide direct evidence that resident microglia in the dorsal horn undergo active cell division after peripheral nerve injury.

Figure 4. Dynamics of microglial proliferation in the spinal dorsal horn after spinal nerve transection.

(a) Representative images of Ki-67 immunostaining in L4 lumbar DH at POD 3 and 5 after SNT (n=6 mice). Scale bar is 150 μm. Co-localization of Ki-67 immunostaining with Iba1+ microglia is shown in Figure S5a. (b) The time course of Ki-67 expressing cells, which peaks at POD3, in the DH after SNT. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Values represent the number of Ki-67+Iba1+ cells (per DH slice) (n = 6 mice per each time point; ***P < 0.001 versus number of Ki67+Iba1− cells at the corresponding time point). (c) Time-lapse images (180 min) of a dividing GFP+ microglia in acute spinal cord slices at POD 3 following SNT. Arrows denote the dividing microglia [parent cells (white arrows); daughter cells (red arrows)] and time is presented as hr:min (n=4 mice). The dotted box shows the region with magnification. Scale bar is 100 μm and 10 μm for lower and higher magnification images, respectively. Two-photon live imaging of microglia proliferation in the DH from spinal slice at POD3 after SNT is presented in Movie S1.

Pharmacological inhibition of microgliosis attenuated neuropathic pain hypersensitivities

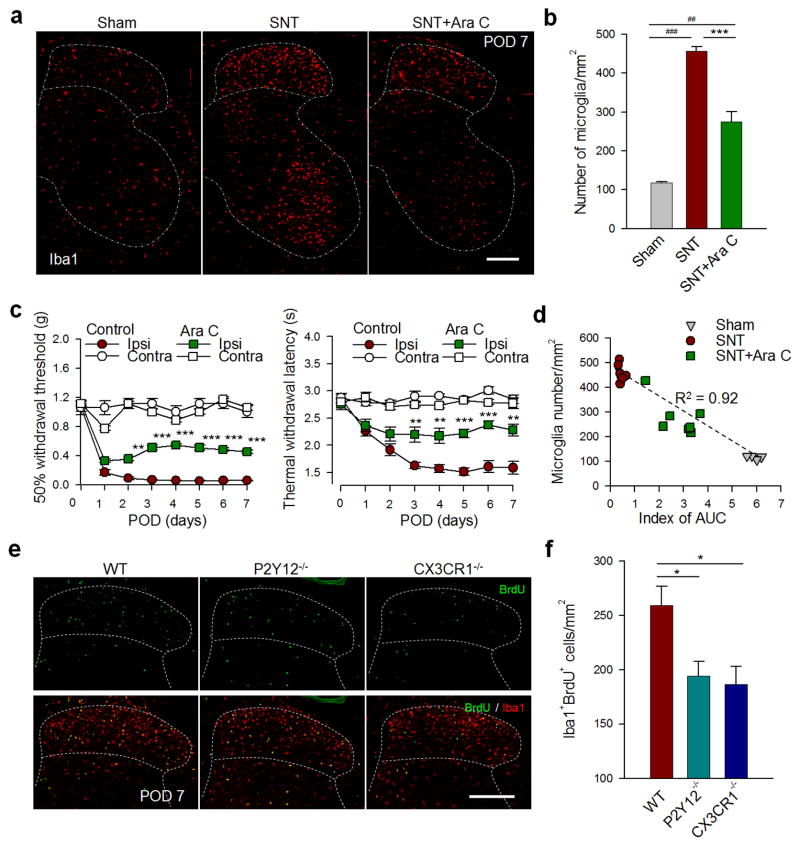

If microglial proliferation is the major driver for microgliosis which is associated with neuropathic pain hypersensitivity, we hypothesize that inhibition of microglial proliferation would attenuate pain after peripheral nerve injury. To test this hypothesis, we intrathecally administrated the anti-mitotic drug cytosine arabinoside (AraC, 50ug in 5μl ACSF, twice/day at POD1–4 and then once/day at POD5–7) immediately after SNT. We found that the number of Iba1+ microglia in the spinal dorsal horn at POD 7 after SNT was significantly reduced by 39.7% in AraC-treated mice than in vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.001, Figure 5a–b). Consistently, AraC treatment almost abolished all increased BrdU+ Iba1+ cells at POD 7 after SNT in ipsilateral dorsal horn (Figures S5c and S5f). Also, there were very few GFAP+ cells or NG2+ cells that were co-localized with BrdU labeling (Figure S5d–f). We found that AraC treatment did not affect GFAP (137 ± 9.9 cells without and 134 ± 8.7 cells with AraC per field of view; n = 5–7; P = 0.83) or NG2 (37.5 ± 2.1 cells without and 34.8 ± 3.6 cells with AraC per field of view; n = 5–6; P = 0.58) cell numbers. Behaviorally, AraC treatment dramatically reduced the SNT-induced thermal hyperalgesia [F (7, 192) = 14.8; Day 3–4, P < 0.01; Day 5–7, P < 0.001] and mechanical allodynia [F (7, 192) = 45.3; Day 2, P < 0.01; Day 3–7, P < 0.001; Figure 5c]. In addition, we observed a positive correlation between the number of dorsal horn microglia and the extent of allodynia after AraC administration (R=0.92; Figure 5d). Therefore, spinal microgliosis due to proliferation directly determines neuropathic pain hypersensitivities after peripheral nerve injury.

Figure 5. Microglial proliferation determines neuropathic pain hypersensitivities after spinal nerve transection.

Anti-mitotic drug cytosine arabinoside (AraC, i.t., 50ug in 5μl ACSF, twice/day at POD 1–4 and then once/day at POD 5–7) effectively decreases the number of Iba1+ microglia after SNT. (a) Representative confocal images of microglia (Iba1 staining) in the ipsilateral spinal cord at POD 7 following SNT in sham, SNT, and SNT+ AraC treated mice (n=4 mice). Scale bar is 200 μm. (b) Summarized data for the number of Iba1+ cell per mm2 in the ipsilateral dorsal horn (lamina I–IV) from the three groups shown in a (n = 4 mice in sham group; 7 mice in SNT and SNT + AraC groups). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.; ***P < 0.001 compared with SNT control; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared with sham. (c) Attenuation of mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia after SNT by intrathecally administered AraC. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (n =7 mice per group; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with SNT control). (d) A positive correlation between the number of microglia in the DH and the extent of allodynia (index of AUC) after AraC administration (n=4 mice in sham group; 7 mice in both SNT and SNT+AraC groups). To further investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying microglial proliferation, we examined microglial proliferation by BrdU labeling (BrdU, i.p. 100mg/kg, 1 pulses/day at POD 1–3) in CX3CR1−/− mice and in P2Y12−/− mice, both have reduced allodynia compared with WT mice (Figure S6a–b). (e) Representative confocal images showing double staining of BrdU+ (green) and Iba1+ (red) cells in the spinal cord DH at POD 7 following SNT in WT, CX3CR1−/− and P2Y12−/− mice (n=4 mice). Scale bar is 200 μm. (f) Summarized data showing the reduced number of BrdU+ Iba1+ cells per mm2 in DH in CX3CR1−/− and P2Y12−/− mice compared with that in WT mice at POD 7 following SNT. All data are mean ± s.e.m. (n=6–7 mice; *P < 0.05 compared with WT mice). Further analysis of microglial proliferation in P2Y12−/− mice is shown in Figure S6c–e.

Purinergic and fractalkine signaling in SNT-induced microglial proliferation

To further investigate the molecular regulators of microglial proliferation after peripheral nerve injury, we turned to microglia-specific receptors CX3CR1 and P2Y12 (Butovsky et al., 2014; Cardona et al., 2006). Consistent with previous reports (Gu et al., 2015; Staniland et al., 2010; Tozaki-Saitoh et al., 2008), neuropathic pain hypersensitivities were attenuated in both CX3CR1−/− [F (4, 100) = 44.6; Day 2, P < 0.01; Day 3, P < 0.001; Day 5, P < 0.05; Day 7, P < 0.05] and P2Y12−/− [F (4, 100) = 30.7; Day 3, P < 0.001; Day 5, P < 0.001; Day 7, P < 0.01] mice compared with WT mice after SNT (Figure S6a–b). We then examined SNT-induced microglial proliferation by BrdU labeling in CX3CR1−/− and P2Y12−/− mice. Interestingly, we found a significant reduction in BrdU+Iba1+ proliferating microglia in the ipsilateral spinal dorsal horn in both CX3CR1−/− and P2Y12−/− mice compared with WT mice at POD7 after SNT (BrdU, i.p., once/day at POD1–3; P < 0.05; Figure 5e–f). Detailed analysis showed a decrease in BrdU+Iba1+ cells starting at POD3 in P2Y12−/− mice compared with those in WT mice after SNT (Figure S6c–e). These results suggest that both CX3CR1 and P2Y12 receptors participate in microglial proliferation and thereby contribute, at least in part, to neuropathic pain hypersensitivities after peripheral nerve injury.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the cellular origin of spinal microgliosis and its contribution to pain hypersensitivities after peripheral nerve injury. Our results show that SNT-induced spinal microgliosis results predominantly from local self-renewal of microglia but not from infiltrating monocytes. Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of SNT-induced microglial proliferation attenuated neuropathic pain hypersensitivities. The current study provides important insights on the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in several folds: (1) We unexpectedly found that monocytes do not infiltrate the spinal cord dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury in contrast to previous studies (Echeverry et al., 2011; Sawada et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2007); (2) We pinpointed that self-renewal of resident microglia is the cellular basis for SNT-induced spinal microgliosis; (3) We characterized the dynamics of microglial proliferation and directly provided visual evidence of dividing spinal microglia after peripheral nerve injury; (4) We found that microglial proliferation contributes to the SNT-induced neuropathic pain and is controlled partially by microglial specific receptors CX3CR1 and P2Y12.

Spinal microgliosis is a characteristic of microglial activation following peripheral nerve injury (Calvo and Bennett, 2012; Tsuda et al., 2005; Zhuo et al., 2011). It was long believed that after peripheral nerve injury, bone-marrow derived monocytes infiltrate the spinal cord dorsal horn and differentiate into parenchymal microglia (Echeverry et al., 2011; Sawada et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2007). Surprisingly, here we found that there are no monocytes entering the spinal dorsal horn within 14 days of SNT injury based on several lines of evidence through multiple approaches, using transgenic CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice, CX3CR1creER: R26RFP reporter mice, P2Y12 and CD169 immunostaining. Using bone marrow chimeras with lethal irradiation, previous studies have observed more than 40% microglial cells in the spinal dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury are derived from bone marrow monocytes (Echeverry et al., 2011; Sawada et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2007). The discrepancy between these studies and ours is not entirely clear, but might be due to the different approaches that were used. It has been proposed that irradiation or bone marrow transplantation may change the overall immune environment and/or impair blood brain/spinal barrier which represents an experimental artifact that cannot be generalized (Ransohoff and Perry, 2009). In favor of this idea, recent studies showed strong hematopoietic cell engrafts in the mice brain in bone marrow chimeras with lethal irradiation while no infiltration of hematopoietic cells were observed in the bone marrow chimeras with parabiosis (Ajami et al., 2007). These studies raised the possibility that circulating cells may not cross the intact blood brain/spinal barrier without irradiation and/or transplantation which is consistent with our current study. Interestingly, previous studies found that peripheral nerve injury increased the permeability of blood spinal cord barrier (Beggs et al., 2010; Echeverry et al., 2011) although we did not observe Evans blue staining in spinal cord at POD 7 after SNT (data not shown). Nevertheless, our study suggest that monocytes are not able to infiltrate the spinal dorsal horn even if there is increased permeability of the blood spinal cord barrier after SNT.

Our study further showed that SNT-induced microgliosis is driven primarily through local proliferation of resident microglia in the spinal dorsal horn. The correlation of nerve injury and microgliosis make it plausible to assume that primary afferent derived injury signals might be the major trigger for microglial proliferation. Indeed, recent studies suggest neuregulin-1 or colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) are critical for microglial proliferation after peripheral nerve injury (Calvo et al., 2010; Guan et al., 2016). Here, we found that two microglia-specific receptors, CX3CR1 and P2Y12, participate in the nerve injury-induced microglial proliferation in the spinal dorsal horn. Our results may explain at least in part the decreased neuropathic pain hypersensitivities in the current study and those in previous studies (Gu et al., 2015; Staniland et al., 2010; Tozaki-Saitoh et al., 2008; Zhuang et al., 2007). Although the precise mechanisms underlying CX3CR1 and P2Y12 in chronic pain are still unclear, studies indeed suggest that both receptors are coupled to P38 expression, which could lead to increased inflammatory responses (Kobayashi et al., 2008; Zhuang et al., 2007). Future studies are needed to address how CX3CR1 and P2Y12 receptors directly or indirectly regulate microglial proliferation in response to peripheral nerve injury. The current study not only furthers our understanding of microglial mechanisms underlying chronic pain, but also provides potential therapeutic strategies targeting microgliosis for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

C57BL/6J mice (wildtype, WT), CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice, CX3CR1creER: Rosa26tdTomato/+ reporter mice, CX3CR1GFP/+ mice, CX3CR1GFP/GFP (CX3CR1−/−) and P2Y12−/− mice were used in the present study. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. All transgenic mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Inc., except the P2Y12−/− mice (gift from Dr. Michael Dailey at the University of Iowa)(Andre et al., 2003; Haynes et al., 2006) and CX3CR1creER mice (gift from Dr. Wen-Biao Gan at New York University)(Parkhurst et al., 2013). CCR2RFP/+:CX3CR1GFP/+ mice were generated by crossbreeding CCR2RFP/RFP mice (Saederup et al., 2010) with CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice (Jung et al., 2000). CX3CR1creER:Rosa26tdTomato/+ reporter mice were generated by crossbreeding CX3CR1CreER mice with Rosa26 tdTomato/+ mice. CX3CR1GFP/+ mice were generated by crossbreeding CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice with C57BL/6J mice. All transgenic mice were on a C57BL/6J background, and are viable and showed no detectable developmental defects. Six- to twelve-week-old age-matched male mice were used in accordance with institutional guidelines, as approved by the animal care and use committee at Rutgers University and Fourth Military Medical University. None of the mice underwent prior experimentation before being used for this study. All animals were housed under controlled temperature humidity and lighting (light: dark 12:12 hr. cycle) with food and water available ad libitum.

Inducible Expression of tdTomato in CNS Resident Microglia

To selective label CNS resident microglia, CX3CR1creER:Rosa26 tdTomato/+ reporter mice were used. Tamoxifen (TM, Sigma) was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma) and administered intraperitoneally (i.p.). Adult CX3CR1creER: Rosa26 tdTomato/+ mice received four doses of TM (150 mg/kg, 20 mg/ml in corn oil) in 48 hr intervals. TM induced the expression of tdTomato in resident microglial and infiltrating monocytes. Since monocytes have a shorter lifespan due to rapid turnover, tdTomato-expressing monocytes are replaced by monocytes lacking tdTomato at 4 wk following TM inductions, while resident microglia still have tdTomato (Parkhurst et al., 2013). Hence, to observe monocyte infiltration, spinal nerve transection or spinal cord contusion injury was performed at 4 wk following TM inductions.

Spinal Nerve Transection (SNT) Surgery

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane in O2 (induction: 4–5% isoflurane; maintenance: 1.5–2.5% isoflurane). Lumbar 4 spinal nerve transection (SNT) surgery was performed as previously described (Chung et al., 2004; Gu et al., 2015). Briefly, a small incision to the skin overlaying L4-S1 was made, followed by retraction of the paravertebral musculature from the vertebral transverse processes. The L4 spinal nerve was identified, lifted slightly, transected, and removed 1–1.5 mm from the end to dorsal root ganglia (DRG). The wound was irrigated with saline and closed in with a two-layer suture by closing the muscles with 6-0 silk sutures and the skin with 5-0 silk sutures. The L4 spinal nerve was exposed without ligation or transection in sham-operated mice. Post-operative day (POD) was used to represent the time point following SNT.

Drug Administration

The thymidine analog bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma) was used to label proliferating and recently postmitotic cells in the spinal cord after SNT surgery. The BrdU solution was diluted in 1M PBS just before use and intraperitoneally administered (i.p. 100mg/kg). To inhibit microglial proliferation, the anti-mitotic drug cytosine arabinoside (AraC, 50 μg in 5 μl ACSF) was intrathecally injected to mice at given time points after SNT. For intrathecal (i.t.) drug administration, mice were hand restricted and injected by direct lumbar puncture between L5 and L6 vertebrae of the spine, using a 10-μL Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Bonaduz AG) with a 31G needle. Successful insertion was indicated by a tail flick response.

Mouse Model of Spinal Cord Contusion Injury, Monocyte Flow Cytometry, Pain Behavioral Tests, Immunohistochemistry, Spinal Cord Slice Preparation and 2-photon Imaging, Quantitative RT-PCR, Statistical Analysis

For further details regarding materials and methods used in this work, please see the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institute of Health (R01NS088627, R21DE025689, T32ES007148), New Jersey Commission on Spinal Cord Research (CSCR15ERG015, CSCR13IRG006), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81200857, 81571351, 81371510). We thank Dr. Michael E. Dailey (University of Iowa) for providing us with P2Y12 knockout mice, Dr. Wen-Biao Gan (New York University) for providing us with CX3CR1CreER/+ mice, and Noriko Goldsmith (Rutgers University) for technical assistance with confocal microscopy.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions

N.G. and J.P. designed and performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.M., X.W., and U.E. performed some behaviors experiments and wrote the manuscript. X.W., D.S., and Y.R. assisted with spinal cord injury experiments. E.D.-B. and W.Y. provided some experimental design and expert discussion of the project. H.D. and L.-J. W. conceived the study, supervised the overall project, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, Rossi FM. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1538–1543. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre P, Delaney SM, LaRocca T, Vincent D, DeGuzman F, Jurek M, Koller B, Phillips DR, Conley PB. P2Y12 regulates platelet adhesion/activation, thrombus growth, and thrombus stability in injured arteries. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:398–406. doi: 10.1172/JCI17864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggs S, Liu XJ, Kwan C, Salter MW. Peripheral nerve injury and TRPV1-expressing primary afferent C-fibers cause opening of the blood-brain barrier. Mol Pain. 2010;6:74. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, Koeglsperger T, Dake B, Wu PM, Doykan CE, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:131–143. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo M, Bennett DL. The mechanisms of microgliosis and pain following peripheral nerve injury. Exp Neurol. 2012;234:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo M, Zhu N, Tsantoulas C, Ma Z, Grist J, Loeb JA, Bennett DL. Neuregulin-ErbB signaling promotes microglial proliferation and chemotaxis contributing to microgliosis and pain after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5437–5450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5169-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, Huang D, Kidd G, Dombrowski S, Dutta R, et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JM, Kim HK, Chung K. Segmental spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain. Methods Mol Med. 2004;99:35–45. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-770-X:035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukic M, Mildner A, Schmidt H, Czesnik D, Bruck W, Priller J, Nau R, Prinz M. Circulating monocytes engraft in the brain, differentiate into microglia and contribute to the pathology following meningitis in mice. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2006;129:2394–2403. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverry S, Shi XQ, Rivest S, Zhang J. Peripheral nerve injury alters blood-spinal cord barrier functional and molecular integrity through a selective inflammatory pathway. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10819–10828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1642-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Brenner D, Llorens-Bobadilla E, Saiz-Castro G, Frank T, Wieghofer P, Hill O, Thiemann M, Karray S, Prinz M, et al. Infiltration of circulating myeloid cells through CD95L contributes to neurodegeneration in mice. J Exp Med. 2015;212:469–480. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu N, Eyo UB, Murugan M, Peng J, Matta S, Dong H, Wu LJ. Microglial P2Y12 receptors regulate microglial activation and surveillance during neuropathic pain. Brain Behav Immun. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.11.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Z, Kuhn JA, Wang X, Colquitt B, Solorzano C, Vaman S, Guan AK, Evans-Reinsch Z, Braz J, Devor M, et al. Injured sensory neuron-derived CSF1 induces microglial proliferation and DAP12-dependent pain. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:94–101. doi: 10.1038/nn.4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SE, Hollopeter G, Yang G, Kurpius D, Dailey ME, Gan WB, Julius D. The P2Y(12) receptor regulates microglial activation by extracellular nucleotides. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1512–1519. doi: 10.1038/nn1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, Littman DR. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, Verkhratsky A. Physiology of microglia. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:461–553. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Yamanaka H, Fukuoka T, Dai Y, Obata K, Noguchi K. P2Y12 receptor upregulation in activated microglia is a gateway of p38 signaling and neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2892–2902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5589-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Pang S, Yu Y, Wu X, Guo J, Zhang S. Proliferation of parenchymal microglia is the main source of microgliosis after ischaemic stroke. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2013;136:3578–3588. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst CN, Yang G, Ninan I, Savas JN, Yates JR, 3rd, Lafaille JJ, Hempstead BL, Littman DR, Gan WB. Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell. 2013;155:1596–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priller J, Flugel A, Wehner T, Boentert M, Haas CA, Prinz M, Fernandez-Klett F, Prass K, Bechmann I, de Boer BA, et al. Targeting gene-modified hematopoietic cells to the central nervous system: use of green fluorescent protein uncovers microglial engraftment. Nat Med. 2001;7:1356–1361. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saederup N, Cardona AE, Croft K, Mizutani M, Cotleur AC, Tsou CL, Ransohoff RM, Charo IF. Selective chemokine receptor usage by central nervous system myeloid cells in CCR2-red fluorescent protein knock-in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Beggs S. Sublime microglia: expanding roles for the guardians of the CNS. Cell. 2014;158:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada A, Niiyama Y, Ataka K, Nagaishi K, Yamakage M, Fujimiya M. Suppression of bone marrow-derived microglia in the amygdala improves anxiety-like behavior induced by chronic partial sciatic nerve ligation in mice. Pain. 2014;155:1762–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staniland AA, Clark AK, Wodarski R, Sasso O, Maione F, D’Acquisto F, Malcangio M. Reduced inflammatory and neuropathic pain and decreased spinal microglial response in fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) knockout mice. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1143–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupin P. Protocols for studying adult neurogenesis: insights and recent developments. Regenerative medicine. 2007;2:51–62. doi: 10.2217/17460751.2.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozaki-Saitoh H, Tsuda M, Miyata H, Ueda K, Kohsaka S, Inoue K. P2Y12 receptors in spinal microglia are required for neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4949–4956. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0323-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Inoue K, Salter MW. Neuropathic pain and spinal microglia: a big problem from molecules in “small” glia. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Cao K, Sun X, Chen Y, Duan Z, Sun L, Guo L, Bai P, Sun D, Fan J, et al. Macrophages in spinal cord injury: phenotypic and functional change from exposure to myelin debris. Glia. 2015;63:635–651. doi: 10.1002/glia.22774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shi XQ, Echeverry S, Mogil JS, De Koninck Y, Rivest S. Expression of CCR2 in both resident and bone marrow-derived microglia plays a critical role in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12396–12406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3016-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang ZY, Kawasaki Y, Tan PH, Wen YR, Huang J, Ji RR. Role of the CX3CR1/p38 MAPK pathway in spinal microglia for the development of neuropathic pain following nerve injury-induced cleavage of fractalkine. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Wu G, Wu LJ. Neuronal and microglial mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Mol Brain. 2011;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.