Abstract

Fear conditioning researches have led to a comprehensive picture of the neuronal circuit underlying the formation of fear memories. In contrast, knowledge about the retrieval of fear memories is much more limited. This disparity may stem from the fact that fear memories are not rigid, but reorganize over time. To bring clarity and raise awareness on the time-dependent dynamics of retrieval circuits, we review current evidence on the neuronal circuitry participating in fear memory retrieval at both early and late time points after conditioning. We focus on the temporal recruitment of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, and its BDNFergic efferents to the central nucleus of the amygdala, for the retrieval and maintenance of fear memories. Finally, we speculate as to why retrieval circuits change across time, and the functional benefits of recruiting structures such as the paraventricular nucleus into the retrieval circuit.

Keywords: Paraventricular thalamus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, long-term memory, BDNF

INTRODUCTION

Animals have an extraordinary ability to associate threatening events with sensory stimuli (e.g., images, smells or sounds). Such memories can persist long after learning1–3, and this persistence is critical for survival4. This evolutionary ability to remember cues that were previously associated with danger allows animals to select the most appropriate defensive responses5, 6. Decades of research on “fear conditioning” have led to a comprehensive understanding of the neuronal circuitry controlling acquisition of fear memories (for recent reviews see:7, 8, 9), but much less is known about circuits for retrieval of these memories.

Part of the challenge in identifying fear retrieval circuits is that memories are not permanently stored into a single region, but are gradually reorganized over time (for review see:10, 11–13). Recent studies in rodents provide evidence supporting a time-dependent reorganization of the fear retrieval circuits following both contextual fear conditioning14–22, as well as auditory fear conditioning23–28. However, a systematic comparison of the different circuits required during early (hours after conditioning) and late (days to weeks after conditioning) retrieval of fear memories is lacking.

In this review, we summarize current evidence on the neuronal circuitry participating in the retrieval of auditory fear memories at early vs. late time points. Prior reviews on the retrieval of auditory fear memories have focused largely on the 24-hour post-conditioning time point, potentially missing temporal changes occurring in the retrieval circuits long after conditioning. We will begin by comparing lesion and pharmacological inactivation studies with more recent findings incorporating optogenetics, chemogenetics (mediated by designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs, DREADDs), and electrophysiological recordings from identified neurons. Next, we will speculate on the functional significance of alterations in retrieval circuits, and how current evidence discussed here could impact the design of future experiments in both laboratory animals and humans.

Early retrieval of fear memories

Before discussing the circuits that mediate the retrieval of fear memories, it is important to review the target areas participating in the acquisition of fear memories. There is a general consensus that the acquisition of auditory fear memories requires the integration of sensory information in the amygdala (for review see:29, 30). Specifically, information about tone and shock originating in cortical and thalamic areas converge onto principal neurons of the lateral nucleus of the amygdala (LA), leading to synaptic changes that store tone-shock associations31–34. Similar conditioning-induced changes in synaptic transmission have been recently reported in the lateral portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala35, 36, an area that is also critical for fear memory formation37–39. In addition to their role in conditioning, LA and CeL are necessary for fear memory retrieval soon after conditioning (up to 24 h). We will discuss this in detail in the following sections.

Amygdala microcircuits necessary for early retrieval

In the last decade, studies using lesions or pharmacological inactivation in rodents indicate that activity in the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA; comprising LA and the basal nucleus of the amygdala) is critical for retrieval of fear memory 24 h following conditioning40–43. LA neurons project to CeL, as well as to the basal nucleus of the amygdala (BA), both of which are connected with the medial portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala44–48. Neurons in CeM then project to downstream regions, such as the periaqueductal gray (PAG) and the hypothalamus, to mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear49, 50. Tone-evoked responses in LA neurons are increased within one hour following fear conditioning51, 52, and persist for several days after learning53–55. Similar conditioned responses 24 h after conditioning have been demonstrated in BA56, 57, and inactivating BA at this time point impairs fear retrieval40, 56. BA contains a population of glutamatergic neurons in which activity is correlated with fear expression (“fear neurons”), and participate in the generation of fear responses by relaying LA activity to the CeM8, 57.

Similar to BA, retrieval of fear memories at the 24 h time point activates neurons in CeM, and pharmacological inactivation of CeM with the GABAA agonist muscimol impairs fear retrieval39, 58. In contrast to CeM, muscimol inactivation of CeL promotes freezing behavior39, consistent with inhibitory control of CeM by CeL. In fact, it has been suggested that the release of CeL-mediated inhibition in CeM is critical for the expression of freezing during retrieval of fear memory36, 39, 59. This disinhibition hypothesis is also supported by electrophysiological findings showing two populations of inhibitory neurons in CeL 24 h following fear conditioning: one exhibiting excitatory tone responses (CeLON neurons), and another exhibiting inhibitory tone responses (CeLOFF neurons)39. The CeLOFF neurons, a fraction of which can be accounted for by their expression of protein kinase C-delta, project to CeM and are hypothesized to drive the tonic inhibition of CeM neurons39, 59. CeLON neurons selectively inhibit their CeLOFF counterpart, which presumably leads to the disinhibition of CeM output neurons during fear memory retrieval.

There also exists a functional dichotomy within CeL based on the discordant expression of the neuropeptide somatostatin (SOM; CeL-SOM+ neurons and CeL-SOM− neurons). Whereas optogenetic silencing of CeL-SOM+ neurons impairs fear memory retrieval, optogenetic activation of CeL-SOM+ neurons induces fear responses in naïve mice36. Additional experiments are necessary to determine if CeL-SOM+ neurons overlap with CeLON neurons. A similar disinhibitory mechanism has been described in the amygdala for the medial intercalated cells (mITCs), a group of GABAergic cells located in the intermediate capsule of the amygdala between BLA and central nucleus of amygdala (CeA)60–62. During early fear retrieval, excitatory inputs from LA neurons excite the dorsal portion of mITCs generating a feed-forward inhibition of their ventral portion. The reduction in activity in the ventral portion of mITCs release CeM output neurons from inhibition, thereby allowing fear responses to occur (for review see:8)

Early retrieval requires the prelimbic cortex

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) has long been suspected of regulating emotional responses in animals and humans63–65. Two subregions of the rodent mPFC, the prelimbic cortex (PL) and the infralimbic cortex (IL), have emerged as being antagonistic to each other in the regulation of fear memories. Whereas PL activity is necessary for fear retrieval soon (24 h) after conditioning27, 42, 66, IL activity at this same time point is critical for fear extinction learning 67–69.

PL neurons display increased tone-evoked firing 24 h after conditioning, which mirror the time course of freezing behavior70, 71. In this way, PL activity predicts the magnitude of fear responses72. Conditioned responses of PL neurons depend on BLA inputs, as pharmacological inactivation of BLA decreased both spontaneous activity and tone responses in putative PL projection neurons73. Consistent with this idea, a recent study combining retrograde tracing with optogenetic techniques demonstrated that “fear neurons” of BA project exclusively to PL, and optogenetic silencing of these projections 24 h after conditioning inhibits fear retrieval74.

Previous neuroanatomical studies have demonstrated that PL not only receives projections from BLA, but also projects to this region75, 76. Silencing of PL projections to BLA with optogenetic techniques 6 h after conditioning impaired fear memory retrieval27, suggesting that PL exerts a top-down modulation of amygdala activity during fear retrieval soon after conditioning. Conditioned increases in PL activity may involve disinhibition, as it was recently shown that PL interneurons expressing parvalbumin (PV+) decrease their activity after conditioning, and optogenetic silencing of these cells augments fear responses77. While these findings suggest a critical role of PL interneurons in fear retrieval, further studies are needed to investigate if the recently described long-range GABAergic neurons in mPFC78 can also contribute to fear memory regulation79.

Later retrieval of fear memories

A growing number of studies indicate that circuits guiding the retrieval of fear memories change with the passage of time after conditioning. Below, we review the evidence supporting a time-dependent reorganization of the fear circuits, beginning with the auditory cortex, a region that is completely dispensable at early time points, but becomes essential at late time points.

Recruitment of auditory cortex for retrieval

Lesions of the auditory cortex shortly before or after fear conditioning do not prevent the acquisition or consolidation or fear memories, suggesting that the auditory thalamus is sufficient to support fear learning in the amygdala80–83. Notably, whereas the auditory cortex is dispensable for the formation of fear memory, the secondary auditory cortex (Te2) has a critical role in the retrieval of fear memory long after conditioning24, 26. Lesions of Te2 performed 30 d, but not 24 h, after conditioning impair fear retrieva 26, and conditioning increases the expression of the neuronal activity marker zif268 in Te2 30 d after, but not 24 h after, learning24, 26. Together, these results suggest that the role played by the auditory cortex in fear conditioning is not restricted to stimulus processing and transmission, but rather, for retrieval of fearful stimuli long after associations are established84.

The recruitment of area Te2 for retrieval of auditory fear memory resembles the time-dependent recruitment of the anterior cingulate cortex (aCC) for retrieval of contextual fear memory13. Retrieval of contextual fear information 24 h after conditioning depends on activity in the hippocampus, but not in the aCC, whereas retrieval 36 d after conditioning depends on activity in the aCC, but not in the hippocampus16. Retrieval of fear memories at 24 h or 36 d time points was associated with an increase in dendritic spine density in the hippocampus or the aCC, respectively21. Interestingly, blocking spine growth in the aCC during the first postconditioning week disrupts memory consolidation85. While these studies suggests a cellular mechanism underlying the time-dependent involvement of the hippocampus and aCC in contextual fear retrieval, whether the Te2 region also undergoes temporal plasticity changes following auditory fear conditioning remains to be determined.

Shifting of retrieval circuits in the prelimbic cortex

Prior studies have demonstrated that cortical areas are necessary for retrieval at late but not early time points. This raises the question as to the mechanisms involved in the transitions of circuits across time. An important clue comes from PL, a structure previously shown to be necessary for 24 h retrieval27, 42, 66, 77. A recent study demonstrated that PL is necessary for retrieval of fear at both 6 h and 7 d after conditioning, but the target of PL efferent fibers shifts across the two time points27. PL neurons projecting to BLA are necessary for retrieval at 6 h (but not 7 d), whereas PL neurons projecting to the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) are required for retrieval at 7 d (but not 6 h) following conditioning. This time-dependent shift between retrieval circuits likely involves different populations of neurons in the PL, because neurons projecting to BLA or PVT are located in different layers of PL27, 76, 86. While further studies on PL circuit dynamics are needed, these findings suggest that time-dependent changes in PL efferents may serve to reorganize retrieval circuits in subcortical targets.

Basolateral amygdala’s role in late retrieval

The BLA has been classically described as a critical region for the retrieval of recently acquired fear memories. However, its role in fear memory retrieval long after conditioning is far less clear, with most of the evidence coming from experiments using post-training lesion techniques. Indeed, excitotoxic lesions of BLA performed 7 days, 14 days, or 16 months after fear conditioning produced significant deficits in fear retrieval3, 87, suggesting that BLA is an important substrate to store remote fear memories. Nevertheless, because lesion techniques provide an inaccurate control of the lesion size, it is difficult to determine whether the effects observed are due to non-specific lesion of adjacent areas (e.g. CeA, ITCs). Recent studies employing newer methodologies have challenged the idea that BLA is a critical site for the retrieval of fear memories several days after conditioning. Inducible silencing of synaptic output from BLA neurons after fear acquisition had no effect on fear retrieval tested 3 days later, suggesting that BLA is dispensable for fear memory retrieval long after conditioning88, 89.

Further evidence that BLA activity is not required for late fear memory retrieval is our finding showing that optogenetic silencing of either BLA neurons or PL-BLA communication blocked the retrieval of 6 h-old, but not 7 d-old fear memories27. Consistent with this, BLA neurons showed increased expression of the neuronal activity marker cFos during fear retrieval at 6 h or 24 h after conditioning, but not 7 d after conditioning27. Altogether, there is increasing evidence that although BLA participates in the acquisition and early retrieval of fear memory, late retrieval of fear memories may occur independent of BLA. A time-limited role of BLA neurons in memory retrieval may augment the availability of BLA neurons for new associations, with more permanent storage of emotional memories occurring in cortical structures (e.g. mPFC) where contextual and emotional information are integrated with circuits involved in decision-making90. While the mechanisms by which fear memories are transferred away from BLA remain unclear, the neuronal circuit underlying the retrieval of fear memories downstream of the mPFC seems to require a previously overlooked structure, the PVT.

Paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus is recruited for retrieval

The PVT is a subdivision of the dorsal midline thalamus that is anatomically connected with multiple brain regions known to be involved in fear regulation, including PL, IL, BLA, CeA and PAG86, 91, 92. A role of PVT in fear retrieval at the 24 h time point has been suggested by previous studies using lesion or pharmacological inactivation93, 94. Extending these findings, a recent study using chemogenetic techniques in mice demonstrated that PVT projections to CeL are essential for fear memory consolidation, as well as for the retrieval of fear memory at the 24 h time point28. A parallel study combining pharmacological inactivation and optogenetic techniques in rats demonstrated that, following conditioning, PVT becomes increasingly necessary for fear memory retrieval27. Unlike BLA, PVT is not required for retrieval 6 h after conditioning, but is required at 24 h and thereafter. In addition to the impairment of fear retrieval, pharmacological inactivation of PVT at late time points (tested at 7 and 28 d) significantly hindered fear memory retrieval in a subsequent drug free session, suggesting that activity in PVT neurons may also be necessary for the maintenance of fear memory27.

These recent findings argue for PVT as an important regulator of fear memories, which becomes critical for fear memory retrieval 24 h after conditioning, and raise the following questions: 1) When does PVT become recruited into the fear memory circuit? 2) How does PVT regulate fear memories? and 3) What are the advantages of PVT recruitment? In the following sections, we will discuss current evidence that may help to answer some of these questions and also identify the critical experiments needed to fill the knowledge gap.

When is PVT recruited into the fear circuit?

Both immunohistochemical and electrophysiological evidence support the notion that PVT is activated early after fear conditioning. PVT displays a significant increase in cFos protein expression immediately after conditioning28, and a fraction of PVT neurons displays increased spontaneous firing rate within 2 h post conditioning27. However, transient pharmacological inactivation of the dorsal midline thalamus, including PVT, immediately prior to conditioning had no effect on fear memory retrieval assessed 24 h later93. In addition, chemogenetic inhibition of PVT neurons, starting from the onset of conditioning, does not affect the fear conditioning-induced synaptic plasticity onto SOM+ CeL neurons – a recently identified cellular process critical for fear memory formation36 – at 3 h following conditioning28. By contrast, the same manipulation does impair this CeL plasticity when assessed at 24 h following conditioning28. One possible explanation for the latter effect is that ongoing PVT activity following conditioning is required for the consolidation of CeL plasticity. Consistently, inhibiting the ongoing PVT activity with a chemogenetic approach that lasts several hours (~10 h)95 is sufficient to impair this consolidation process28.

Consistent with this hypothesis, the proportion of PVT neurons showing either increased tone responses or changes in spontaneous firing rate increases significantly from 2 h to 24 h post-conditioning27. These observations highlight PVT’s importance for the maintenance, albeit not for the induction, of fear-evoked synaptic plasticity. Together with the finding that PVT becomes critical for fear memory retrieval 24 h, but not 6 h, after conditioning27, 28, current evidence indicates that PVT regulates both the long-term expression and maintenance of fear memory. In contrast, various features of short-term memory such as fear-induced synaptic plasticity (3 h) and fear retrieval (6 h) appear to be PVT-independent.

Another important question regarding the time-dependent recruitment of PVT is whether PVT neurons activated early on following fear conditioning are different from those activated later on, when PVT becomes critical for fear memory retrieval and maintenance. A partial answer to this question may be found in the observation that PVT neurons displaying tone responses 2 h after conditioning are distinct from those neurons displaying tone responses 24 h after conditioning27. Nevertheless, to fully address this question, one would need to systematically compare large populations of PVT neurons that are activated by fear memory retrieval at early vs. late time points. Currently, a wide range of novel experimental approaches, which include calcium and/or voltage imaging of identified neuronal ensembles in behaving animals would help to tackle this issue96, 97.

The PVT-amygdala circuit in fear memory regulation

While moderate projections from PVT are found in multiple amygdala nuclei, CeL is the main amygdala recipient of PVT efferent fibers91, 92. Rats with PVT lesions exhibit a significant increase in stress-induced cFos expression in the CeL98. Similarly, increased cFos expression was observed in CeL when PVT was inactivated during a fear retrieval session93, suggesting that PVT normally serves to suppress the recruitment of CeL neurons. CeL inhibition is currently thought to be a critical step in the retrieval of fear memories39, 59, raising the possibility that PVT may control fear memory retrieval by promoting CeL inhibition. However, such inhibition is unlikely a result of inhibitory projections from PVT, as the midline thalamus is largely devoid of GABAergic neurons99, 100.

A closer look at the PVT-CeL microcircuit in mice reveals that PVT projections preferentially targets SOM+ neurons of CeL, and enhance their excitability28. In addition, optogenetic activation of PVT afferents in CeL causes indirect inhibiton of SOM− neurons28, consistent with previous observations that SOM+ CeL neurons are powerful local inhibitors36. Thus, activation of SOM+ neurons could be the mechanism by which PVT promotes CeL local inhibition and thereby fear retrieval. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying PVT’s role in fear memory consolidation and maintenance are far less clear. A potential answer may be found in the observation that the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mediates PVT-CeL communication28.

BDNF is a critical regulator of neuronal plasticity and synaptic function101, 102, and has been heavily implicated in memory formation103. In the fear circuit, BDNF regulates both fear learning in the BLA104, 105 and fear extinction in the mPFC106, 107. A pivotal role of BDNF has also been reported for the persistence of fear memories108, 109, suggesting that BDNF signaling in PVT-CeL may be a potential candidate to mediate the maintenance of fear memories. Indeed, BDNF communication between PVT and CeL neurons is critical for both fear learning and the long-term expression of fear-induced CeL synaptic plasticity28. In addition, because BDNF mediates PVT-CeL neurotransmission, BDNF may subserve PVT’s function in fear memory maintenance, although direct evidence for this is lacking.

As previously mentioned, inactivation of PVT inputs to the CeA during a 7d fear memory retrieval session impairs the subsequent retrieval of fear memory one day later27. This observation is consistent with the idea that PVT-CeA communication is essential for the re-consolidation of fear memory. Surprisingly, however, fear memory re-consolidation is not impaired by intra-PVT blockade of MAP kinase27, a critical mediator of neuronal plasticity110. A possible explanation for this finding is that, although PVT may participate in the maintenance and/or re-consolidation of fear memory within the amygdala, it may not be a site of plasticity itself. Nevertheless, increased expression of MAP kinase in the PVT has been associated with impaired retention of extinction memories in adolescent rats111. Activation of MAP kinase signaling in PVT may strengthen the formation of fear memories, leading to impaired retrieval of extinction memories during adolescence.

What are the advantages of recruiting PVT into the fear circuit?

Anatomical studies have demonstrated that PVT is reciprocally interconnected with multiple limbic, hypothalamic and cortical regions, including the mPFC86, 91, 92. Our understanding of the functional role of PVT is mainly based on lesion studies, which characterize PVT as part of the brain circuitry controlling both arousal mediated by negative states and adaptive responses to stress (for review see:112, 113). Studies in rodents have shown that PVT is activated by a variety of physical and psychological stressors including restraint114, 115, foot shock116, sleep deprivation117, and forced swim118, 119. In turn, PVT activity has been shown to modulate neuroendocrine120, 121, autonomic114, 122 and behavioral responses to stress123. Together, these studies suggest that recruitment of PVT during the establishment of long-term fear memories may serve to coordinate adaptive responses to stress.

Consistent with this, functional impairments in PVT have been implicated in maladaptive responses such as increased vulnerability to stress, exacerbated anxiety phenotypes and depressive-like behaviors such as despair, anhedonia and lack of motivation112, 124. Notably, pharmacological activation of PVT produces anxiety and fear-like behavior in rats125, 126, and increased activity in PVT neurons projecting to the CeA is correlated with depressive-like behavior in rats119, reinforcing the idea that dysfunction in PVT circuits may lead to the maladaptive expression of fear and/or aversive behaviors.

Recent evidence has also implicated PVT in the development of drug seeking and addiction-related behaviors127, suggesting that malfunctioning in this thalamic subregion may be also involved in inappropriate retrieval of reward-associated memories. PVT’s involvement in the modulation of maladaptive forms of both aversive and reward processes is intriguing given that there is a high comorbidity between mood, anxiety and addiction disorders in humans128. However, whether a link exists between PVT dysfunction and the co-expression of these pathological phenotypes has yet to be determined. Consistent with the idea of coordinating both positive and negative emotional states, PVT is activated by cues associated with either food129, 130 or drug reward131–133, as well as by cues associated with aversive taste134 or fearful stimuli27, 134, 135. Therefore, encoding of negative valence could occur via activation of PVT projections to CeA (as discussed above), whereas encoding of positive valence could occur through activation of PVT projections to the nucleus accumbens, as previously suggested136, 137.

In addition to its documented role in both defensive and reward-seeking behaviors, PVT has also been implicated in the modulation of circadian rhythms and energy balance in rats114. Notably, PVT displays diurnal variations in neuronal activity122, and lesions of PVT abolish light-induced phase shifts in circadian rhythmicity138. Together, these findings depict a potential role for PVT as an important regulator of homeostasis and state-dependent behavior. Therefore, unlike BLA, PVT may be well positioned to integrate defensive behaviors elicited by aversive memories with adaptive biological responses, which include arousal, stress-adaptation, regulation of circadian rhythms, and control of food intake and energy balance (see Fig 2).

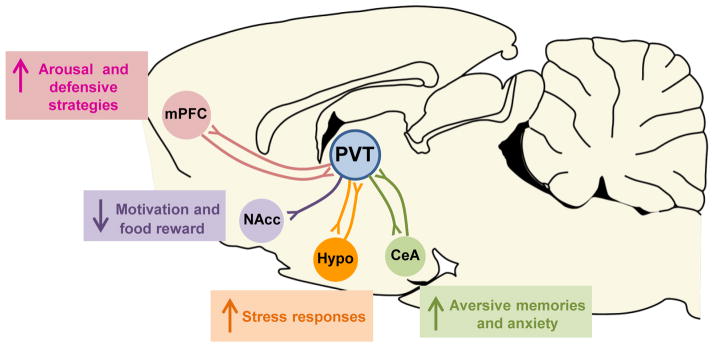

Fig. 2. Recruitment of PVT into the fear circuit may serve to integrate aversive memories with adaptive biological responses.

The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) is reciprocally interconnected with the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the hypothalamus (Hypo), and the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA). In addition, PVT is the major source of inputs to the nucleus accumbens (NAcc). This pattern of anatomical connections places PVT in a central position to integrate aversive memories and anxiety (through connections with CeA) with adaptive biological responses such as arousal and defensive strategies (through connections with the mPFC), motivation and control of food intake (through projections to the NAcc), and regulation of circadian rhythms and stress responses (through connections with the hypothalamus).

CONCLUSIONS

The studies reviewed here support the idea that the circuits mediating the retrieval of fear memories change with the passage of time following conditioning. Although much remains to be discovered regarding the mechanisms mediating the reorganization of retrieval circuits, the present findings emphasize the importance of investigating - at the molecular, cellular and circuit level - how aversive memories are retrieved across time. Prior studies of retrieval circuits have uniquely focused at the 24 hours post-conditioning time point, therefore ignoring temporal changes that occur later after the acquisition phase. Understanding how fear retrieval circuits are restructured over time may be of relevance for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), given that PTSD patients seek medical assistance weeks or even months after the initial trauma139.

The advance of optogenetic tools, combined with calcium imaging and single-unit recording of identified neurons, have provided a unique opportunity to understand the temporal dynamic of memory reorganization. By manipulating and recording the activity of defined neural ensembles during behavior, future studies will identify time-dependent changes in the neural circuits mediating long-term retrieval of aversive memories. In addition, imaging studies focusing on the temporal modifications of retrieval circuits in humans may help to elucidate how aversive memories persist over time, thereby providing alternative targets for pharmacological treatment in patients with anxiety disorders.

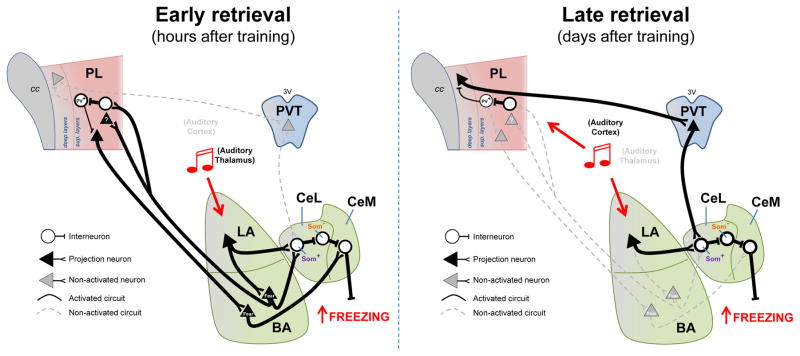

Fig. 1. Temporal reorganization of the circuits necessary for retrieval of auditory fear memories.

Left - Retrieval of fear memories at early time points after conditioning recruits reciprocal activity between the amygdala and PL. During early retrieval, the conditioned tone activates auditory thalamus inputs to LA. Increased activity in LA neurons activates Som+ neurons in CeL, thereby disinhibiting CeM output neurons that mediate fear responses. Increased activity in LA neurons also activates BA neurons interconnected with PL, thereby allowing a top-down control of fear retrieval. Right - Retrieval of fear memories at late time points after conditioning recruits activity in PL neurons projecting to PVT, as well as PVT neurons projecting to CeL. During late retrieval, the conditioned tone activates auditory cortex inputs to both LA and PL. Increased activity in PL interneurons inhibits PV+ interneurons, thereby disinhibiting PL neurons projecting to PVT. Increased activity in PVT neurons activates Som+ neurons in CeL, and consequently disinhibits CeM output neurons that mediate fear responses. Legend: PL= prelimbic cortex, sup= superficial, PVT= paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, LA= lateral amygdala, BA= basal amygdala, CeL= lateral portion of the central amygdala, CeM= medial portion of the central amygdala, cc= corpus callosum, 3V= third ventricle, PV+= parvalbumin positive neurons, Som+= somastotatin positive neurons, Som−= somatostatin negative neurons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grant K99-MH105549 to F.H.D-M; NIMH grants R01-MH058883 and P50-MH086400, and a grant from the University of Puerto Rico President’s Office to G.J.Q; and NIMH grant R01-MH101214 to B.L..

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maren S. Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:897–931. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gale GD, Anagnostaras SG, Godsil BP, Mitchell S, Nozawa T, Sage JR, et al. Role of the basolateral amygdala in the storage of fear memories across the adult lifetime of rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24(15):3810–3815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4100-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darwin C, editor. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: Fontana Press; 1872. [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeDoux JE. Evolution of human emotion: a view through fear. Prog Brain Res. 2012;195:431–442. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nesse RM. Evolutionary explanations of emotions. Hum Nat. 1990;1(3):261–289. doi: 10.1007/BF02733986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herry C, Johansen JP. Encoding of fear learning and memory in distributed neuronal circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(12):1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/nn.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duvarci S, Pare D. Amygdala microcircuits controlling learned fear. Neuron. 2014;82(5):966–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luthi A, Luscher C. Pathological circuit function underlying addiction and anxiety disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(12):1635–1643. doi: 10.1038/nn.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKenzie S, Eichenbaum H. Consolidation and reconsolidation: two lives of memories? Neuron. 2011;71(2):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudai Y. The restless engram: consolidations never end. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:227–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tayler KK, Wiltgen BJ. New methods for understanding systems consolidation. Learn Mem. 2013;20(10):553–557. doi: 10.1101/lm.029454.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankland PW, Bontempi B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(2):119–130. doi: 10.1038/nrn1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, Fanselow MS. Temporally graded retrograde amnesia of contextual fear after hippocampal damage in rats: within-subjects examination. J Neurosci. 1999;19(3):1106–1114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01106.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Einarsson EO, Pors J, Nader K. Systems reconsolidation reveals a selective role for the anterior cingulate cortex in generalized contextual fear memory expression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(2):480–487. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frankland PW, Bontempi B, Talton LE, Kaczmarek L, Silva AJ. The involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in remote contextual fear memory. Science. 2004;304(5672):881–883. doi: 10.1126/science.1094804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frankland PW, Ding HK, Takahashi E, Suzuki A, Kida S, Silva AJ. Stability of recent and remote contextual fear memory. Learn Mem. 2006;13(4):451–457. doi: 10.1101/lm.183406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gafford GM, Parsons RG, Helmstetter FJ. Memory accuracy predicts hippocampal mTOR pathway activation following retrieval of contextual fear memory. Hippocampus. 2013;23(9):842–847. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goshen I, Brodsky M, Prakash R, Wallace J, Gradinaru V, Ramakrishnan C, et al. Dynamics of retrieval strategies for remote memories. Cell. 2011;147(3):678–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maren S, Aharonov G, Fanselow MS. Neurotoxic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1997;88(2):261–274. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Restivo L, Vetere G, Bontempi B, Ammassari-Teule M. The formation of recent and remote memory is associated with time-dependent formation of dendritic spines in the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29(25):8206–8214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0966-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SH, Teixeira CM, Wheeler AL, Frankland PW. The precision of remote context memories does not require the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(3):253–255. doi: 10.1038/nn.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beeman CL, Bauer PS, Pierson JL, Quinn JJ. Hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex contributions to trace and contextual fear memory expression over time. Learn Mem. 2013;20(6):336–343. doi: 10.1101/lm.031161.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon JT, Jhang J, Kim HS, Lee S, Han JH. Brain region-specific activity patterns after recent or remote memory retrieval of auditory conditioned fear. Learn Mem. 2012;19(10):487–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.025502.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narayanan RT, Seidenbecher T, Kluge C, Bergado J, Stork O, Pape HC. Dissociated theta phase synchronization in amygdalo- hippocampal circuits during various stages of fear memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(6):1823–1831. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sacco T, Sacchetti B. Role of secondary sensory cortices in emotional memory storage and retrieval in rats. Science. 2010;329(5992):649–656. doi: 10.1126/science.1183165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Do-Monte FH, Quinones-Laracuente K, Quirk GJ. A temporal shift in the circuits mediating retrieval of fear memory. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature14030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penzo MA, Robert V, Tucciarone J, De Bundel D, Wang M, Van Aelst L, et al. The paraventricular thalamus controls a central amygdala fear circuit. Nature. 2015;519(7544):455–459. doi: 10.1038/nature13978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pape HC, Pare D. Plastic synaptic networks of the amygdala for the acquisition, expression, and extinction of conditioned fear. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(2):419–463. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansen JP, Cain CK, Ostroff LE, LeDoux JE. Molecular mechanisms of fear learning and memory. Cell. 2011;147(3):509–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watabe AM, Ochiai T, Nagase M, Takahashi Y, Sato M, Kato F. Synaptic potentiation in the nociceptive amygdala following fear learning in mice. Mol Brain. 2013;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolff SB, Grundemann J, Tovote P, Krabbe S, Jacobson GA, Muller C, et al. Amygdala interneuron subtypes control fear learning through disinhibition. Nature. 2014;509(7501):453–458. doi: 10.1038/nature13258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sehgal M, Ehlers VL, Moyer JR., Jr Learning enhances intrinsic excitability in a subset of lateral amygdala neurons. Learn Mem. 2014;21(3):161–170. doi: 10.1101/lm.032730.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sears RM, Schiff HC, LeDoux JE. Molecular mechanisms of threat learning in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;122:263–304. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420170-5.00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penzo MA, Robert V, Li B. Fear conditioning potentiates synaptic transmission onto long-range projection neurons in the lateral subdivision of central amygdala. J Neurosci. 2014;34(7):2432–2437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4166-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Penzo MA, Taniguchi H, Kopec CD, Huang ZJ, Li B. Experience-dependent modification of a central amygdala fear circuit. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(3):332–339. doi: 10.1038/nn.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goosens KA, Maren S. Pretraining NMDA receptor blockade in the basolateral complex, but not the central nucleus, of the amygdala prevents savings of conditional fear. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117(4):738–750. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilensky AE, Schafe GE, Kristensen MP, LeDoux JE. Rethinking the fear circuit: the central nucleus of the amygdala is required for the acquisition, consolidation, and expression of Pavlovian fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2006;26(48):12387–12396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4316-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciocchi S, Herry C, Grenier F, Wolff SB, Letzkus JJ, Vlachos I, et al. Encoding of conditioned fear in central amygdala inhibitory circuits. Nature. 2010;468(7321):277–282. doi: 10.1038/nature09559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anglada-Figueroa D, Quirk GJ. Lesions of the basal amygdala block expression of conditioned fear but not extinction. J Neurosci. 2005;25(42):9680–9685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2600-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goosens KA, Maren S. Contextual and auditory fear conditioning are mediated by the lateral, basal, and central amygdaloid nuclei in rats. Learn Mem. 2001;8(3):148–155. doi: 10.1101/lm.37601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sierra-Mercado D, Padilla-Coreano N, Quirk GJ. Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(2):529–538. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koo JW, Han JS, Kim JJ. Selective neurotoxic lesions of basolateral and central nuclei of the amygdala produce differential effects on fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2004;24(35):7654–7662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1644-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pitkanen A, Savander V, LeDoux JE. Organization of intra-amygdaloid circuitries in the rat: an emerging framework for understanding functions of the amygdala. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(11):517–523. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stefanacci L, Farb CR, Pitkanen A, Go G, LeDoux JE, Amaral DG. Projections from the lateral nucleus to the basal nucleus of the amygdala: a light and electron microscopic PHA-L study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323(4):586–601. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ottersen OP. Connections of the amygdala of the rat. IV: Corticoamygdaloid and intraamygdaloid connections as studied with axonal transport of horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1982;205(1):30–48. doi: 10.1002/cne.902050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pitkanen A, Stefanacci L, Farb CR, Go GG, LeDoux JE, Amaral DG. Intrinsic connections of the rat amygdaloid complex: projections originating in the lateral nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1995;356(2):288–310. doi: 10.1002/cne.903560211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savander V, Miettinen R, Ledoux JE, Pitkanen A. Lateral nucleus of the rat amygdala is reciprocally connected with basal and accessory basal nuclei: a light and electron microscopic study. Neuroscience. 1997;77(3):767–781. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viviani D, Charlet A, van den Burg E, Robinet C, Hurni N, Abatis M, et al. Oxytocin selectively gates fear responses through distinct outputs from the central amygdala. Science. 2011;333(6038):104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1201043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LeDoux JE, Iwata J, Cicchetti P, Reis DJ. Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. J Neurosci. 1988;8(7):2517–2529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02517.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Repa JC, Muller J, Apergis J, Desrochers TM, Zhou Y, LeDoux JE. Two different lateral amygdala cell populations contribute to the initiation and storage of memory. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(7):724–731. doi: 10.1038/89512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quirk GJ, Repa C, LeDoux JE. Fear conditioning enhances short-latency auditory responses of lateral amygdala neurons: parallel recordings in the freely behaving rat. Neuron. 1995;15(5):1029–1039. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rogan MT, Staubli UV, LeDoux JE. Fear conditioning induces associative long- term potentiation in the amygdala. Nature. 1997;390(6660):604–607. doi: 10.1038/37601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goosens KA, Hobin JA, Maren S. Auditory-evoked spike firing in the lateral amygdala and Pavlovian fear conditioning: mnemonic code or fear bias? Neuron. 2003;40(5):1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00728-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diaz-Mataix L, Debiec J, LeDoux JE, Doyere V. Sensory-specific associations stored in the lateral amygdala allow for selective alteration of fear memories. J Neurosci. 2011;31(26):9538–9543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5808-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amano T, Duvarci S, Popa D, Pare D. The fear circuit revisited: contributions of the basal amygdala nuclei to conditioned fear. J Neurosci. 2011;31(43):15481–15489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3410-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herry C, Ciocchi S, Senn V, Demmou L, Muller C, Luthi A. Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits. Nature. 2008;454(7204):600–606. doi: 10.1038/nature07166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duvarci S, Popa D, Pare D. Central amygdala activity during fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2011;31(1):289–294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haubensak W, Kunwar PS, Cai H, Ciocchi S, Wall NR, Ponnusamy R, et al. Genetic dissection of an amygdala microcircuit that gates conditioned fear. Nature. 2010;468(7321):270–276. doi: 10.1038/nature09553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nitecka L, Ben-Ari Y. Distribution of GABA-like immunoreactivity in the rat amygdaloid complex. J Comp Neurol. 1987;266(1):45–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.902660105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Millhouse OE. The intercalated cells of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1986;247(2):246–271. doi: 10.1002/cne.902470209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Royer S, Martina M, Pare D. An inhibitory interface gates impulse traffic between the input and output stations of the amygdala. J Neurosci. 1999;19(23):10575–10583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10575.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Damasio AR. On some functions of the human prefrontal cortex. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;769:241–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb38142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barbas H. Complementary roles of prefrontal cortical regions in cognition, memory, and emotion in primates. Adv Neurol. 2000;84:87–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morgan MA, Romanski LM, LeDoux JE. Extinction of emotional learning: contribution of medial prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1993;163(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90241-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corcoran KA, Quirk GJ. Activity in prelimbic cortex is necessary for the expression of learned, but not innate, fears. J Neurosci. 2007;27(4):840–844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5327-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Do-Monte FH, Manzano-Nieves G, Quinones-Laracuente K, Ramos-Medina L, Quirk GJ. Revisiting the role of infralimbic cortex in fear extinction with optogenetics. J Neurosci. 2015;35(8):3607–3615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3137-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang CH, Maren S. Strain difference in the effect of infralimbic cortex lesions on fear extinction in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124(3):391–397. doi: 10.1037/a0019479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burgos-Robles A, Vidal-Gonzalez I, Santini E, Quirk GJ. Consolidation of fear extinction requires NMDA receptor-dependent bursting in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2007;53(6):871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burgos-Robles A, Vidal-Gonzalez I, Quirk GJ. Sustained conditioned responses in prelimbic prefrontal neurons are correlated with fear expression and extinction failure. J Neurosci. 2009;29(26):8474–8482. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0378-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baeg EH, Kim YB, Jang J, Kim HT, Mook-Jung I, Jung MW. Fast spiking and regular spiking neural correlates of fear conditioning in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11(5):441–451. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sotres-Bayon F, Quirk GJ. Prefrontal control of fear: more than just extinction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20(2):231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sotres-Bayon F, Sierra-Mercado D, Pardilla-Delgado E, Quirk GJ. Gating of fear in prelimbic cortex by hippocampal and amygdala inputs. Neuron. 2012;76(4):804–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Senn V, Wolff SB, Herry C, Grenier F, Ehrlich I, Grundemann J, et al. Long-range connectivity defines behavioral specificity of amygdala neurons. Neuron. 2014;81(2):428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDonald AJ, Mascagni F, Guo L. Projections of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices to the amygdala: a Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;71(1):55–75. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vertes RP. Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse. 2004;51(1):32–58. doi: 10.1002/syn.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Courtin J, Chaudun F, Rozeske RR, Karalis N, Gonzalez-Campo C, Wurtz H, et al. Prefrontal parvalbumin interneurons shape neuronal activity to drive fear expression. Nature. 2014;505(7481):92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee AT, Vogt D, Rubenstein JL, Sohal VS. A class of GABAergic neurons in the prefrontal cortex sends long-range projections to the nucleus accumbens and elicits acute avoidance behavior. J Neurosci. 2014;34(35):11519–11525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1157-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bravo-Rivera C, Diehl MM, Roman-Ortiz C, Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Rosas-Vidal LE, Bravo-Rivera H, et al. Long-range GABAergic neurons in the prefrontal cortex modulate behavior. J Neurophysiol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/jn.00861.2014. jn 00861 02014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Romanski LM, LeDoux JE. Bilateral destruction of neocortical and perirhinal projection targets of the acoustic thalamus does not disrupt auditory fear conditioning. Neurosci Lett. 1992;142(2):228–232. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90379-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Campeau S, Davis M. Involvement of subcortical and cortical afferents to the lateral nucleus of the amygdala in fear conditioning measured with fear-potentiated startle in rats trained concurrently with auditory and visual conditioned stimuli. J Neurosci. 1995;15(3 Pt 2):2312–2327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02312.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Romanski LM, LeDoux JE. Equipotentiality of thalamo-amygdala and thalamo-cortico-amygdala circuits in auditory fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 1992;12(11):4501–4509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04501.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.LeDoux JE, Sakaguchi A, Reis DJ. Subcortical efferent projections of the medial geniculate nucleus mediate emotional responses conditioned to acoustic stimuli. J Neurosci. 1984;4(3):683–698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-03-00683.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grosso A, Cambiaghi M, Concina G, Sacco T, Sacchetti B. Auditory cortex involvement in emotional learning and memory. Neuroscience. 2015;299:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vetere G, Restivo L, Cole CJ, Ross PJ, Ammassari-Teule M, Josselyn SA, et al. Spine growth in the anterior cingulate cortex is necessary for the consolidation of contextual fear memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(20):8456–8460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li S, Kirouac GJ. Sources of inputs to the anterior and posterior aspects of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Brain Struct Funct. 2012;217(2):257–273. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maren S, Aharonov G, Stote DL, Fanselow MS. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the basolateral amygdala are required for both acquisition and expression of conditional fear in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110(6):1365–1374. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.6.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bertocchi I, Arcos-Diaz D, Botta P, Treviño M, Dogbevia G, Luthi A. Cortical localization of fear memory. Abstract Society for Neuroscience meeting; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bertocchi I, Arcos-Diaz D, Botta P, Dogbevia G, Luthi A. Fear and aversive learning and memory: amygdala and extended amygdala circuits. Abstract Society for Neuroscience meeting; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Euston DR, Gruber AJ, McNaughton BL. The role of medial prefrontal cortex in memory and decision making. Neuron. 2012;76(6):1057–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moga MM, Weis RP, Moore RY. Efferent projections of the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359(2):221–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vertes RP, Hoover WB. Projections of the paraventricular and paratenial nuclei of the dorsal midline thalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508(2):212–237. doi: 10.1002/cne.21679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Padilla-Coreano N, Do-Monte FH, Quirk GJ. A time-dependent role of midline thalamic nuclei in the retrieval of fear memory. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li Y, Dong X, Li S, Kirouac GJ. Lesions of the posterior paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus attenuate fear expression. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:94. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alexander GM, Rogan SC, Abbas AI, Armbruster BN, Pei Y, Allen JA, et al. Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron. 2009;63(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Helmchen F, Denk W, Kerr JN. Miniaturization of two-photon microscopy for imaging in freely moving animals. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2013;2013(10):904–913. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top078147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen JL, Andermann ML, Keck T, Xu NL, Ziv Y. Imaging neuronal populations in behaving rodents: paradigms for studying neural circuits underlying behavior in the mammalian cortex. J Neurosci. 2013;33(45):17631–17640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3255-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Spencer SJ, Fox JC, Day TA. Thalamic paraventricular nucleus lesions facilitate central amygdala neuronal responses to acute psychological stress. Brain Res. 2004;997(2):234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Glutamate- and GABA-containing neurons in the mouse and rat brain, as demonstrated with a new immunocytochemical technique. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229(3):374–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bentivoglio M, Balercia G, Kruger L. The specificity of the nonspecific thalamus: the midline nuclei. Prog Brain Res. 1991;87:53–80. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lu B, Nagappan G, Lu Y. BDNF and synaptic plasticity, cognitive function, and dysfunction. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;220:223–250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45106-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zagrebelsky M, Korte M. Form follows function: BDNF and its involvement in sculpting the function and structure of synapses. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Pt C):628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cunha C, Brambilla R, Thomas KL. A simple role for BDNF in learning and memory? Front Mol Neurosci. 2010;3:1. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.001.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rattiner LM, Davis M, French CT, Ressler KJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor B involvement in amygdala-dependent fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2004;24(20):4796–4806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5654-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Andero R, Heldt SA, Ye K, Liu X, Armario A, Ressler KJ. Effect of 7,8- dihydroxyflavone, a small-molecule TrkB agonist, on emotional learning. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(2):163–172. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rosas-Vidal LE, Do-Monte FH, Sotres-Bayon F, Quirk GJ. Hippocampal--prefrontal BDNF and memory for fear extinction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(9):2161–2169. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Peters J, Dieppa-Perea LM, Melendez LM, Quirk GJ. Induction of fear extinction with hippocampal-infralimbic BDNF. Science. 2010;328(5983):1288–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1186909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Katche C, Slipczuk L, Rossato JI, Goldin A, et al. BDNF is essential to promote persistence of long-term memory storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(7):2711–2716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711863105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ou LC, Yeh SH, Gean PW. Late expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the amygdala is required for persistence of fear memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;93(3):372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wiegert JS, Bading H. Activity-dependent calcium signaling and ERK-MAP kinases in neurons: a link to structural plasticity of the nucleus and gene transcription regulation. Cell Calcium. 2011;49(5):296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baker KD, Richardson R. Forming competing fear learning and extinction memories in adolescence makes fear difficult to inhibit. Learn Mem. 2015;22(11):537–543. doi: 10.1101/lm.039487.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hsu DT, Kirouac GJ, Zubieta JK, Bhatnagar S. Contributions of the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the regulation of stress, motivation, and mood. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:73. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kirouac GJ. Placing the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus within the brain circuits that control behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;56:315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bhatnagar S, Dallman M. Neuroanatomical basis for facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to a novel stressor after chronic stress. Neuroscience. 1998;84(4):1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.O’Mahony CM, Sweeney FF, Daly E, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Restraint stress-induced brain activation patterns in two strains of mice differing in their anxiety behaviour. Behav Brain Res. 2010;213(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bubser M, Deutch AY. Stress induces Fos expression in neurons of the thalamic paraventricular nucleus that innervate limbic forebrain sites. Synapse. 1999;32(1):13–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199904)32:1<13::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Semba K, Pastorius J, Wilkinson M, Rusak B. Sleep deprivation-induced c-fos and junB expression in the rat brain: effects of duration and timing. Behav Brain Res. 2001;120(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Battaglia DF, Akil H, Watson SJ. Pattern and time course of immediate early gene expression in rat brain following acute stress. Neuroscience. 1995;64(2):477–505. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhu L, Wu L, Yu B, Liu X. The participation of a neurocircuit from the paraventricular thalamus to amygdala in the depressive like behavior. Neurosci Lett. 2011;488(1):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bhatnagar S, Huber R, Nowak N, Trotter P. Lesions of the posterior paraventricular thalamus block habituation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to repeated restraint. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14(5):403–410. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1331.2002.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jaferi A, Nowak N, Bhatnagar S. Negative feedback functions in chronically stressed rats: role of the posterior paraventricular thalamus. Physiol Behav. 2003;78(3):365–373. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Colavito V, Tesoriero C, Wirtu AT, Grassi-Zucconi G, Bentivoglio M. Limbic thalamus and state-dependent behavior: The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamic midline as a node in circadian timing and sleep/wake-regulatory networks. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;54:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Heydendael W, Sharma K, Iyer V, Luz S, Piel D, Beck S, et al. Orexins/hypocretins act in the posterior paraventricular thalamic nucleus during repeated stress to regulate facilitation to novel stress. Endocrinology. 2011;152(12):4738–4752. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kasahara T, Takata A, Kato TM, Kubota-Sakashita M, Sawada T, Kakita A, et al. Depression-like episodes in mice harboring mtDNA deletions in paraventricular thalamus. Mol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Li Y, Li S, Wei C, Wang H, Sui N, Kirouac GJ. Orexins in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus mediate anxiety-like responses in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212(2):251–265. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1948-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Li Y, Li S, Wei C, Wang H, Sui N, Kirouac GJ. Changes in emotional behavior produced by orexin microinjections in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95(1):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Matzeu A, Zamora-Martinez ER, Martin-Fardon R. The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus is recruited by both natural rewards and drugs of abuse: recent evidence of a pivotal role for orexin/hypocretin signaling in this thalamic nucleus in drug-seeking behavior. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:117. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Russo SJ, Nestler EJ. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(9):609–625. doi: 10.1038/nrn3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Igelstrom KM, Herbison AE, Hyland BI. Enhanced c-Fos expression in superior colliculus, paraventricular thalamus and septum during learning of cue-reward association. Neuroscience. 2010;168(3):706–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Schiltz CA, Bremer QZ, Landry CF, Kelley AE. Food-associated cues alter forebrain functional connectivity as assessed with immediate early gene and proenkephalin expression. BMC Biol. 2007;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dayas CV, McGranahan TM, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Stimuli linked to ethanol availability activate hypothalamic CART and orexin neurons in a reinstatement model of relapse. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(2):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.James MH, Charnley JL, Flynn JR, Smith DW, Dayas CV. Propensity to ‘relapse’ following exposure to cocaine cues is associated with the recruitment of specific thalamic and epithalamic nuclei. Neuroscience. 2011;199:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Matzeu A, Cauvi G, Kerr TM, Weiss F, Martin-Fardon R. The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus is differentially recruited by stimuli conditioned to the availability of cocaine versus palatable food. Addict Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/adb.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Yasoshima Y, Scott TR, Yamamoto T. Differential activation of anterior and midline thalamic nuclei following retrieval of aversively motivated learning tasks. Neuroscience. 2007;146(3):922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Beck CH, Fibiger HC. Conditioned fear-induced changes in behavior and in the expression of the immediate early gene c-fos: with and without diazepam pretreatment. J Neurosci. 1995;15(1 Pt 2):709–720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00709.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, Choi EA, McNally GP. Paraventricular thalamus mediates context-induced reinstatement (renewal) of extinguished reward seeking. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(4):802–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Parsons MP, Li S, Kirouac GJ. Functional and anatomical connection between the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus and dopamine fibers of the nucleus accumbens. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500(6):1050–1063. doi: 10.1002/cne.21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Salazar-Juarez A, Escobar C, Aguilar-Roblero R. Anterior paraventricular thalamus modulates light-induced phase shifts in circadian rhythmicity in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283(4):R897–904. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00259.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.AmericanPsychiatricAssociation. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, D.C: 2013. [Google Scholar]