Abstract

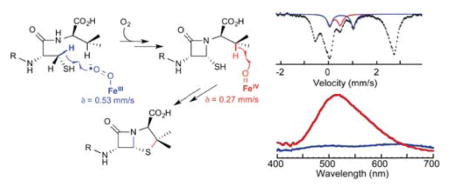

The enzyme isopenicillin N synthase (IPNS) installs the β-lactam and thiazolidine rings of the penicillin core into the linear tripeptide, L-δ-aminoadipoyl-L-Cys-D-Val (ACV), on the pathways to a number of important antibacterial drugs. A classic set of enzymological and crystallographic studies by Baldwin and co-workers established that this overall four-electron oxidation occurs by a sequence of two oxidative cyclizations, with the β-lactam ring being installed first and the thiazolidine ring second. Each phase requires cleavage of an aliphatic C–H bond of the substrate: the pro-S-CCys,β-H bond for closure of the β-lactam ring, and the CVal,β-H bond for installation of the thiazolidine ring. IPNS uses a mononuclear non-heme-iron(II) cofactor and dioxygen as co-substrate to cleave these C–H bonds and direct the ring closures. Despite the intense scrutiny to which the enzyme has been subjected, the identities of the oxidized iron intermediates that cleave the C–H bonds have been addressed only computationally; no experimental insight into their geometric or electronic structures has been reported. In this work, we have employed a combination of transient-state-kinetic and spectroscopic methods, together with the specifically deuterium-labeled substrates, A[d2-C]V and AC[d8-V], to identify both C–H-cleaving intermediates. The results show that they are high-spin Fe(III)-superoxo and high-spin Fe(IV)-oxo complexes, respectively, in agreement with published mechanistic proposals derived computationally from Baldwin’s founding work.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after Sir Alexander Fleming’s ingenious – albeit somewhat fortuitous – discovery of the antimicrobial activity exhibited by a secretion from a Penicillium mold,1 the compound exhibiting this activity, which Fleming termed penicillin, revolutionized medicine.2–4 The chemical moiety responsible for penicillin’s antimicrobial activity is the β-lactam ring. β-lactam antibiotics irreversibly form a covalent acyl-adduct with the catalytically essential serine residue of transpeptidase, an enzyme essential to the biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan component of the bacterial cell wall.5 Unfortunately, extensive use of penicillin and other β-lactams for the treatment of bacterial infections has led to widespread resistance.6 This resistance arises from β-lactamase enzymes, which hydrolyze the β-lactam ring, forming products that are innocuous to transpeptidase and the bacteria.7 In efforts to combat resistance, other less readily hydrolyzed β-lactams, such as carbapenems, have been put into clinical practice, and inhibitors of the β-lactamases, such as clavulanic acid,8 have been co-formulated with penicillins in combination drugs (e.g., Augmentin).9

Early work revealed that penicillin is derived from the tripeptide δ-(L-α-aminoadipoyl)-L-cysteinyl-D-valine (ACV).10,11 This precursor is produced by the enzyme ACV synthetase, a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase that condenses the monomeric precursors, L-α-aminoadipoate, L-cysteine, and L-valine, as it epimerizes Cα of the valine.12–15 Conversion of ACV to isopenicillin N (IPN), a reaction that installs both the β-lactam and thiazolidine rings (Scheme 1), is catalyzed by the mononuclear non-heme-iron(II) [MNH-Fe(II)] enzyme, isopenicillin N synthase (IPNS).16–19 IPN is then further processed in different ways to produce the useful β-lactam antibiotics, such as, for example, penicillin G and the cephalosporins.9,19

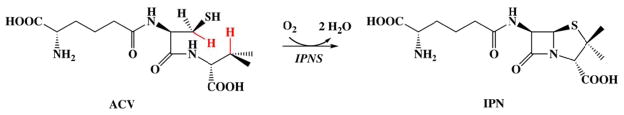

Scheme 1.

Reaction catalyzed by IPNS. Hydrogen atoms abstracted during the reaction are highlighted in red.

IPNS belongs to the large and functionally diverse class of MNH-Fe(II) enzymes that couple the activation and four-electron reduction of O2 to the oxidation (e.g. hydroxylation, halogenation, or desaturation) of their substrates.20–24 Because most MNH-Fe(II) enzymes catalyze two-electron oxidation of their primary substrates, they often require a co-substrate, which is oxidized to provide the other two electrons required for the complete reduction of O2. The three most commonly used co-substrates are 2-(oxo)glutarate (2OG), which is decarboxylated to CO2 and succinate,20,21,25 tetrahydrobiopterin, which is hydroxylated at the C4a position,20,21,26 and NAD(P)H, which is oxidized to NAD(P)+.20,21,27 IPNS belongs to the small but growing group of enzymes that extract all four electrons from their primary substrate and therefore do not require a co-substrate.18–21,23,28–35 Among these enzymes, IPNS is unique because it catalyzes the cleavage of two aliphatic C-H bonds.18,19

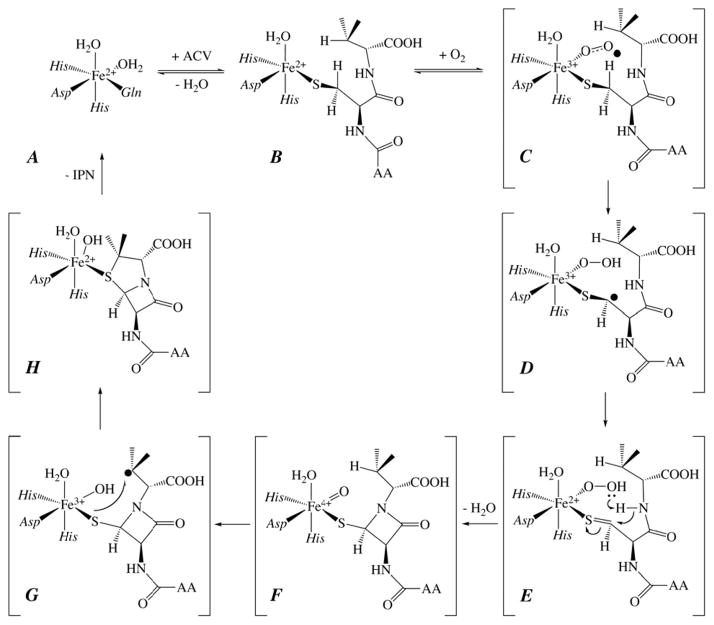

Extensive enzymological studies18,19 and X-ray crystal structures of multiple enzyme complexes36–39 by Baldwin and co-workers, as well as more recent computational studies,40–43 resulted in the mechanistic hypothesis shown in Scheme 2. According to this hypothesis, the reaction proceeds in two phases, each resulting in a two-electron-oxidative cyclization. The first phase, formation of the β-lactam ring, is initiated by cleavage of the pro-S-CCys,β-H bond (step C→D in Scheme 2). An inner-sphere electron transfer from the resultant coordinated thioalkyl radical to the Fe(III) site yields a state with an Fe(II)-hydroperoxo complex and thioaldehyde (E). Heterolysis of the O-O bond coupled to attack of the amide on the thiocarbonyl yields an Fe(IV)-oxo (ferryl) complex with a cis-coordinated thiolate from the monocyclic β-lactam intermediate (F). The second phase of the reaction, which closes the thiazolidine ring, begins with ferryl-mediated cleavage of the CVal,β-H bond (F→G). Attack of the valinyl radical on the coordinated sulfur atom yields the product, isopenicillin N, with its new thioether moiety coordinated to the Fe(II) site (H).

Scheme 2.

Mechanistic hypothesis for the IPNS reaction arising from prior work of Baldwin and co-workers. AA denotes the δ-(L-α-aminoadipoyl) side chain.

The first evidence that formation of the β-lactam ring precedes formation of the thiazolidine ring was provided by competition experiments employing site-specifically deuterium-labeled ACV substrates.17 A selection effect against processing of labeled substrate [a deuterium kinetic isotope effect (D-KIE) on kcat/KM] was observed for the case of CCys,β but not CVal,β substitution, implying that CCys,β-H cleavage occurs before and CVal,β-H cleavage after the first irreversible step in the mechanism. However, either individual substitution elicited a relatively large (> 5) D-KIE on kcat,17 and simultaneous substitution of both positions yielded an even larger effect, demonstrating that both steps are partially rate-limiting for catalytic turnover.

The founding work of Baldwin and coworkers provided compelling evidence for the sequence of ring-closure steps shown in Scheme 2, but, to our knowledge, no published experimental work has directly addressed the identities of the key C–H-bond-cleaving oxidized iron intermediates that initiate the cyclizations. Importantly, the aforementioned large D-KIEs on kcat suggested that it should be possible to promote accumulation of either C-H-cleaving intermediate in a single-turnover by use of the appropriately deuterium-labeled substrate.44–46 In this work, we have leveraged these large D-KIEs for the direct spectroscopic and computational characterization of both C-H-cleaving intermediates. With unlabeled ACV substrate, the CVal,β-H-cleaving intermediate accumulates signficantly, and the preceding CCys,β-H-cleaving complex is barely detectable. Use of the appropriate selectively deuterated substrate, δ-(L-α-aminoadipoyl)-L-3,3-[2H]2-cysteine-D-valine (A[d2-C]V) or δ-(L-α-aminoadipoyl)-L-cysteine-D-2,3,4,4,4,4′,4′,4′-[2H]8-valine (AC[d8-V]), promotes greater accumulation of the intermediate that cleaves that C–H bond, owing to the large D-KIE. Comparison of their spectroscopic characteristics to those of other known enzyme and inorganic complexes and analysis by density functional theory (DFT) calculations suggest that the CCys,β-H-cleaving and CVal,β-H-cleaving intermediates are high-spin Fe(III)-superoxo and high-spin Fe(IV)-oxo (ferryl) complexes, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and methods

Procedures for over-expression and purification of Aspergillus nidulans IPNS are described in Supporting Information. Activity of IPNS was verified by LC/MS analysis (Figure S1). All reagents were obtained commercially (see Supporting Information), except for AC[d8-V], which was synthesized chemically (see Supporting Information) and the identities and purities of synthetic intermediates and products were assessed by NMR spectroscopy (Figures S1–S7).

Preparation of solutions for stopped-flow absorption and freeze-quench Mössbauer spectroscopies

Concentrated apo-IPNS was made anoxic by using a Schlenk line, as previously described,47 transferred into an anoxic chamber (MBraun, Peabody, MA), and mixed in the appropriate ratio with O2-free Fe(II) and ACV stock solutions to allow for formation of the reactant complex, IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV. Specific reaction conditions are given in the figure legends.

Stopped-flow absorption-spectroscopic experiments

Stopped-flow absorption (SF-abs) experiments were performed in an Applied Photophysics SX1.8MV instrument (Surrey, UK) at 5 °C with a 1 cm path length, as previously described.47 The SF-abs unit was housed in the MBraun anoxic chamber, and data were obtained with either a photodiode array detector (PDA) or a photomultiplier tube detector (PMT). Specific reaction conditions are given in the figure legends. The IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV reactant and IPNS•Fe(II)•IPN product complexes are both nearly transparent in the visible region of the spectrum, and so transient absorption in this region arises exclusively from intermediate states. In experiments with all-protium ACV or AC[d8-V], only the Fe(IV)-oxo contributes to this absorption at reaction times longer than ~ 5 ms, and so SF-abs kinetic traces monitored at 515 nm could be analyzed according to the equation (Eq. 2) for the concentration of an intermediate (the ferryl complex) in a sequence of two consecutive, irreversible steps (Eq. 1), in which the reactant (IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV), R, is converted to the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate with an apparent first-order rate constant of k1, the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate decays to the product (IPNS•Fe(II)•IPN), P, with a first-order rate constant of k2, [R]0 is the concentration of the reactant complex at t = 0, and Δε515 is the difference between the molar absorption coefficients of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate and R (or P).

| (1) |

| (2) |

SF-abs experiments monitoring the absorbance changes at 515 nm in the reaction of the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V complex with O2 were simulated with the kinetic model shown in Eq. 3, which involves (i) reversible combination of O2 and R, with rate constants k1 (forward) and k−1 (reverse), to yield the Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate, (ii) decay of the Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate to the ferryl intermediate with a rate constant of k2, and (iii) decay of the ferryl intermediate to P with a rate constant of k3. The ΔA515-vs-time trace from an identical experiment with unlabeled substrate was also analyzed according to the same model to obtain an estimate of the D-KIE.

| (3) |

It was assumed that R and P absorb equally, so that ΔA515 directly reflects accumulation of the more intensely absorbing intermediates. This assumption is justified by the observation that A515 at t = 0 and t → ∞ are equal. The ΔA515-vs-time traces from reactions carried out with either unlabeled ACV or A[d2-C]V were simulated with the software KinTek Explorer (KinTek Corporation, Snow Shoe, PA). During analysis, k1 and k−1 refined to values similar to those obtained independently,48 and k3 was constrained to be identical to the value determined from analysis of the ΔA515-vs-time traces from the reaction with unlabeled ACV according to Eq. 2. The error analysis for the kinetic parameters was carried using the FitSpace feature of KinTek Explorer.

Mössbauer spectroscopy

Samples for Mössbauer spectroscopy were prepared by reacting the IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex with O2 at 5 °C and rapidly freezing at varying reaction times in cold (~ 125 K) 2-methylbutane, as previously described.47 Specific conditions are given in the figure legends. Control samples of the IPNS•Fe(II) and IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complexes were prepared in the absence of O2 and hand frozen without exposure to air. Mössbauer spectra were recorded on spectrometers from Seeco (Edina, MN), as previously described,47 and were simulated by using the program WMOSS (www.wmoss.org, Seeco, Edina, MN). The simulations were either carried out assuming Lorentzian line shape (positive values of line width, Γ) or Voigt line shape (negative values of Γ). Some of the simulations are based on the commonly used spin Hamiltonian (Eq. 4),49 in which the first three terms quantify the electron Zeeman effect and zero field splitting (ZFS) of the electron-spin ground state, the fourth term represents the interaction between the electric field gradient and the nuclear quadrupole moment, the fifth term describes the magnetic hyperfine interactions of the electronic spin with the 57Fe nucleus, and the last term represents the 57Fe nuclear Zeeman interaction.

| (4) |

Computational Methods

Cluster models were constructed from the crystal structure of the NO adduct of IPNS (PDB: 1BLZ).38 Specifically, the active-site model contains an iron center that is coordinated by two 4-methylimidazole ligands (mimicking His214 and His270) and one acetate ligand (mimicking Asp216) in a facial arrangement, and one H2O occupying the equatorial plane. Cartesian coordinates of the carbon atoms of the methyl groups, which correspond to the Cβ atoms of the amino acid residues, were kept frozen during optimizations.

Geometry optimizations were performed by using the B3LYP50,51 density functional along with the semi-empirical van der Waals corrections.52 Scalar relativistic effects were taken into account by using the zeroth-order regular approximation (ZORA),53–55 and implemented following the model potential approximation of van Wüllen.56 The ZORA-TZVP (Fe, O, N and S) and ZORA-SV(P) (C and H) basis sets57,58 were utilized. The RIJCOSX59 approximations were used to accelerate the calculations in combination with the auxiliary basis sets TZV/J (Fe, O, N and S) and SV/J (remaining atoms).60 The protein environment was crudely modeled by the conductor like screen model (COSMO)61 with the dielectric constant set to 4.0.62

The Mössbauer spectroscopic parameters were computed by using the same density functional as in the geometry-optimization step. The calculation employed the CP(PPP)63 basis set for Fe, the TZVP64 basis set for O, N, and S, and the SV(P) basis set65 for the remaining atoms. Isomer shifts (δ) were calculated from the electron densities at the Fe nuclei (ρ0) employing the linear regression (Eq. 5):

| (5) |

Here, C, α and β are the fit parameters; their values for different combinations of the density functionals and basis sets have been reported.66 Quadrupole splitting parameters (ΔEQ) were obtained from electric field gradients, Vi (i = x, y, z; Vi are the eigenvalues of the electric field gradient tensor), employing a nuclear quadrupole moment Q(57Fe) = 0.16 barn:67

| (6) |

Here, η = (Vx − Vy)/Vz is the asymmetry parameter. The magnetic hyperfine coupling tensor, A, of the 57Fe center was calculated by accounting for the isotropic Fermi contact term, the first-order traceless dipolar contribution, and the second-order non-traceless spin-orbit contribution. The Fermi-contact contributions for high-spin ferric and ferryl species were scaled by a factor of 1.81 according published work.67 Spin-orbit contributions to the hyperfine tensors were calculated as second order properties by employing the coupled perturbed (CP) Kohn-Sham theory.68 The iron magnetic hyperfine coupling constants, , of the “genuine” antiferromagnetic state were calculated from the magnetic hyperfine coupling constants, , of the corresponding broken symmetry state by conversion into “site values” and multiplication with the spin projection coefficients, Ci:69

| (7) |

The contributions of spin orbit coupling (SOC) to ZFS were calculated by the linear response theory70 employing the hybrid B3LYP density functional. Here, the SOC contribution to the ZFS tensor is written as:

| (8) |

In Eq. 8, M = 0, ±1 denotes contributions to the SOC term from excited states with S′ = S ± 1 (S > 1/2 is the total spin quantum number of the electronic state for which the ZFS tensor is computed), fm(S) is a spin-dependent prefactor ( ) and is a shorthand notation for a spin-orbit linear response function. In a DFT framework, it is related to the derivatives of generalized spin-densities, as previously described.70 The spin-spin coupling contributions to ZFSs were calculated from the equation of McWeeny and Mizuno,71

| (9) |

in which the spin density matrix, Pα-β, was obtained on the basis of the spin-unrestricted natural orbital (UNO) determinant.72 All computations in this work were carried out with the ORCA program package.73

RESULTS

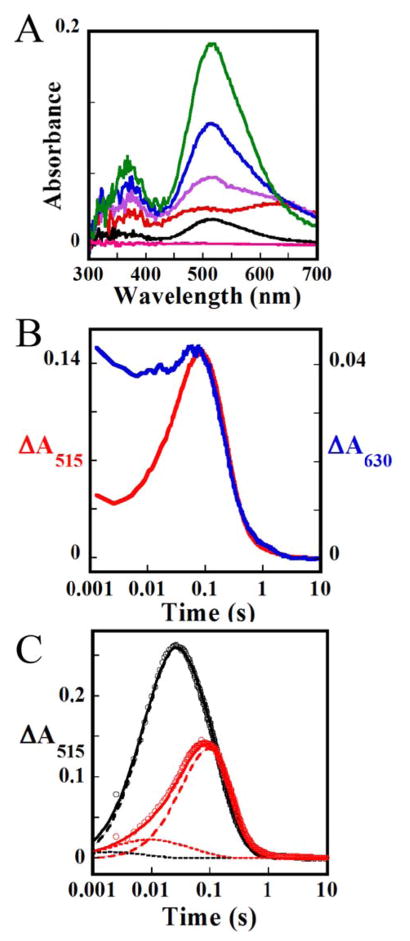

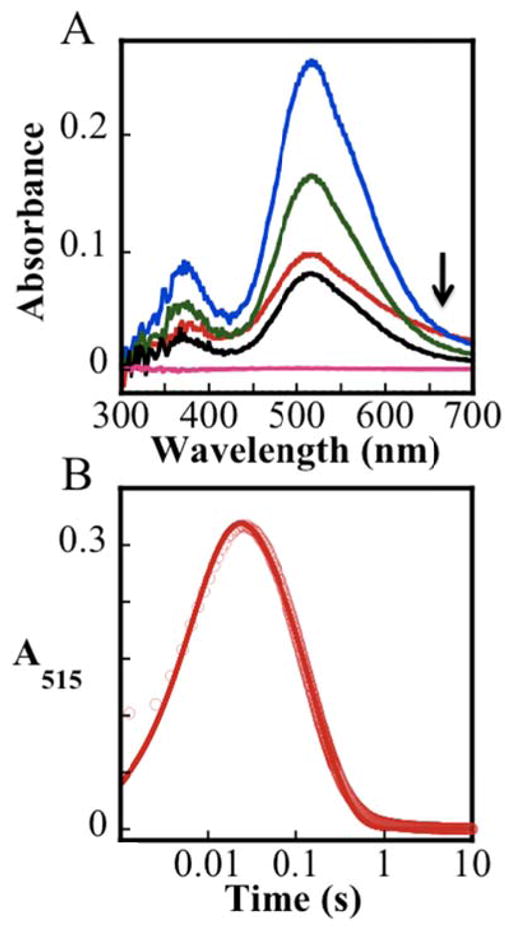

SF-abs evidence for accumulation of an intermediate during the reaction of the IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex with O2

Time-dependent absorption spectra obtained after mixing of the IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex with O2–saturated buffer at 5 °C under single-turnover conditions (with ACV limiting) exhibit transient absorption in the visible region reflecting the accumulation of an intermediate (Figure S8A). The corresponding spectra from the control experiment in which O2 was omitted (Figure S8B) do not change with time, thus confirming that the spectral changes arise from the reaction of IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV with O2. Subtracting the spectrum of the O2-free control from the spectra of the reaction removes contributions from the protein and possible contaminants (Figure 1A). The difference spectra reveal that the intermediate exhibits absorption bands centered at ~360 nm and ~515 nm. The ΔA515-vs-time trace from this reaction (Figure 1B) reveals that the intermediate accumulates maximally at ~25 ms and decays completely by ~1 s. The trace can be analyzed according to a kinetic model involving two irreversible, consecutive reactions with apparent first-order rate constants of k1 = 125 s−1 and k2 = 7 s−1 (red line in Figure 1B).74 The data in Figure 1A also provide a first hint of the accumulation of a preceding intermediate, as comparison of the 2-ms spectrum (Figure 1A, red trace) to the later spectra reveals a low-energy shoulder at very early reaction times (arrow). Accumulation of this precursor is confirmed by additional experiments described below.

Figure 1.

Stopped-flow absorption data from the reaction of the IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex with O2. (A) Difference spectra generated by subtracting from experimental spectra acquired 0.002 s (red), 0.020 s (blue), 0.10 s (green), 0.20 s (black), and 2.0 s (pink) after mixing of a solution of the IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex (1.5 mM IPNS, 1.5 mM Fe(II), 0.5 mM ACV in 100 mM MOPS, pH 7.2) with an equal volume of oxygenated buffer (100% O2 at 5 °C, estimated to have 1.8 mM O2 112) the corresponding spectra from a matched control experiment lacking O2. (B) ΔA515 kinetic trace from the experiment in A (red circles). The red line is a fit with the parameters quoted in the text.

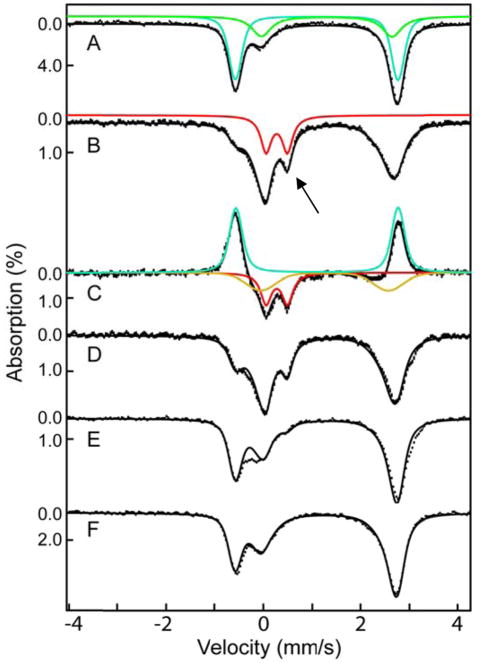

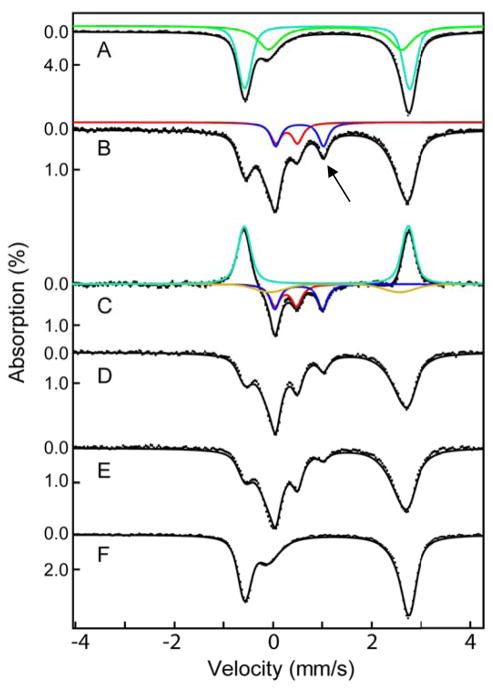

Mössbauer-spectroscopic evidence for an Fe(IV) intermediate

Freeze-quench Mössbauer-spectroscopic (FQ-Möss) experiments afforded insight into the nature of the intermediate detected in the SF-abs experiments.49,75,76 The 4.2-K/zero-field spectrum of the reactant complex (Figure 2, top, vertical bars) can be simulated as a weighted superposition of a sharp and well-defined quadrupole doublet (δ1 = 1.10 mm/s, |ΔEQ,1| = 3.35 mm/s, and Γ = −0.25 mm/s, 65 % of total intensity, turquoise line) and a broad quadrupole doublet (δ2 = 1.30 mm/s, |ΔEQ,2| = 2.68 mm/s, and Γ = −0.61 mm/s, 35 % of total intensity, green line). The parameters are typical for high-spin Fe(II) sites and are virtually identical to those of the ternary IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex (δ1 = 1.11 mm/s and ΔEQ,1 = 3.43 mm/s) and the binary IPNS•Fe(II) complex (δ2 = 1.30 mm/s and ΔEQ,2 = 2.70 mm/s), respectively, reported for Cephalosporium acremonium IPNS.77 Consistent with previous results, only ~70% of the added Fe(II) yields the ternary IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex, as determined from analysis of the Mössbauer spectra.77 The unusual breadth of the quadrupole doublet assigned to the binary IPNS•Fe(II) complex suggests heterogeneity in this state.

Figure 2.

4.2-K/zero-field Mössbauer spectra of samples prepared by reacting IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex with O2 at 5 °C and freeze quenching after the indicated reaction times. Spectrum of an O2-free solution of the reactant IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex (1.8 mM IPNS, 1.8 mM Fe(II) and 20 mM ACV in 100 mM MOPS, 10% glycerol, pH 8.3, A) and spectra of samples prepared by mixing the reactant complex (above) with an oxygen-saturated solution of buffer (at 5 °C, ~1.8 mM O2) in a 1:2 (v/v) ratio and freeze-quenching after reaction times of 0.020 s (B), 0.050 s (D), 0.25 s (E), or 60 s (F) are shown as vertical bars. Spectrum C is the difference spectrum B – A. The solid green, turquoise, red, and gold lines are simulated quadrupole doublets matching the spectra of the IPNS•Fe(II), IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV, and IPNS•Fe(II)•IPN complexes and Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate, respectively; the parameters used to generate them is given in the text. The arrow marks the high-energy line of the spectrum of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate.

The 4.2-K/zero-field Mössbauer spectra of samples prepared by reacting the IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex with O2 at 5 °C for 0.020, 0.12, 0.45, or 90 s (Figure 2, vertical bars) before freeze-quenching reveal changes associated with the reaction. Most notably, a peak at ~ +0.5 mm/s (Figure 2, black arrow) reaches maximum intensity in the spectrum of the 0.020-s sample and then decays. This peak is the high-energy line of a quadrupole doublet associated with a reaction intermediate. Its parameters can be determined by subtracting the spectrum of the reactant control sample from that of the 0.020-s sample, which allows the position of the low-energy line of the quadrupole doublet to be discerned. Analysis of this difference spectrum reveals that the reaction results in conversion of 55 % of the reactant IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex (simulated with the above parameters, turquoise line pointing upwards) to 28 % of the new quadrupole doublet with parameters (δ = 0.27 mm/s, |ΔEQ| = 0.44 mm/s, and Γ = 0.26 mm/s, red line in Figure 2) similar to those of high-spin Fe(IV)-oxo complexes in other MNH-Fe(II) enzymes in addition to 27 % of a second new, broad quadrupole doublet with parameters characteristic of high-spin Fe(II) complexes (δ = 1.27 mm/s, |ΔEQ| = 2.62 mm/s, and Γ = −0.75 mm/s, 27 %, gold line in Figure 2).24 Mössbauer spectra collected in strong externally applied fields (Figure S11) confirm that, like the other known ferryl enzyme complexes in these enzymes, the IPNS Fe(IV) intermediate has an S = 2 ground state. The high-field spectra further reveal that the IPNS complex exhibits more pronounced anisotropy in the xy plane than the other high-spin ferryl intermediates (see Table 1 and Supporting Information for analysis of these spectra). The third, broad quadrupole doublet required to account for the difference spectrum is attributable to one or more Fe(II) complex(es) formed during the reaction, likely including the IPNS•Fe(II)•IPN product complex.

Table 1.

Key structural parameters and comparison of calculated and experimental spin Hamiltonian parameters of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate.

| Parameter | I | II | III | experimental |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-Ooxo (Å) | 1.645 | 1.642 | 1.637 | |

| Fe-S (Å) | 2.327 | 2.706 | 2.705 | |

| Fe-OH2O/OH (Å) | 2.235 | 1.831 | 1.843 | |

| D (cm−1) | 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 10 |

| E/D | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.09 |

| δ (mm/s) | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.27 |

| ΔEQ (mm/s) | −0.93 | −0.69 | +0.30 | −0.44 |

| η | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| A (MHz) | −21.9 −15.5 −32.4 |

−16.1 −8.8 −25.8 |

−17.3 −11.3 −27.3 |

−23.7 −17.8 −41.3 |

The entire set of time-dependent spectra can be analyzed as weighted superpositions of the above four quadrupole doublets, with the contribution of the IPNS•Fe(II) complex fixed at the value determined from the spectrum of the reactant control sample (an assumption based on the observation for other MNH-Fe(II) enzymes that the substrate-free form reacts sluggishly with O2).78 The features of the Fe(IV)-oxo complex account for 28 %, 21 %, 5 %, and < 2 % of the spectra of the 0.020-s, 0.12-s, 0.45-s, and 90-s samples, respectively. The quantities of the four species are summarized in Table S1.

Comparison of the time-dependencies of ΔA515 and the relative area of the Fe(IV)-associated quadrupole doublet from SF-abs and FQ-Mössbauer experiments carried out under nearly identical reaction conditions confirms that the absorption bands at 360 nm and 515 nm are associated with the Fe(IV)-oxo complex (Figures S9 and S10). Under the assumption that the reactant IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complex does not absorb in this spectral region, this comparison affords an estimate of the molar absorptivity of the Fe(IV) species at 515 nm as 2.7 mM−1cm−1,.

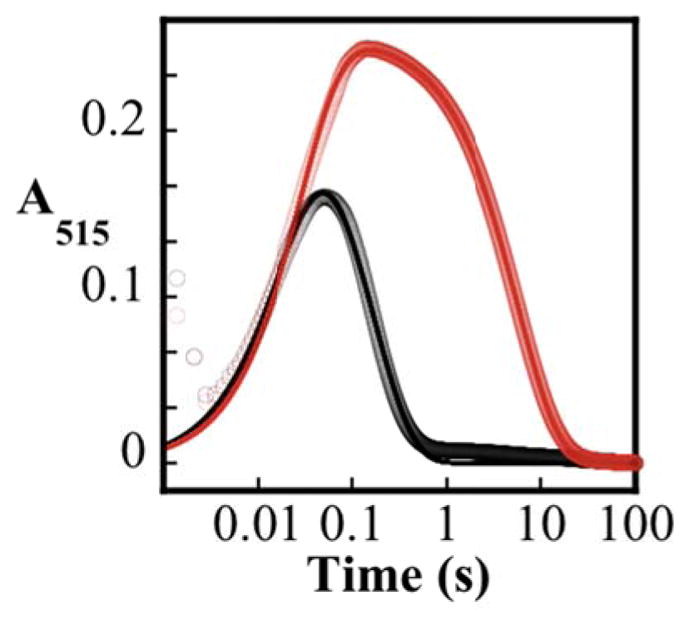

Evidence that the Fe(IV) complex is the CVal,β-H-cleaving intermediate

The assignment of the absorbing intermediate on the basis of its Mössbauer parameters as a high-spin Fe(IV) complex suggests that it could be the CVal,β-H-cleaving complex, F, in Scheme 2. We therefore tested for a D-KIE on its decay in the presence of AC[d8-V].78–82 The ΔA515-vs-time traces from matched experiments with natural-abundance (Figure 3, black trace) and valine-labeled (AC[d8-V], with > 98 % 2H at the target position, red trace) ACV substrates reveal a very large effect on decay of the Fe(IV) intermediate with no effect on ferryl formation. Analysis of the traces according to Eq. 2 yields an apparent first-order rate constant of formation (k1) of ~ 40 s−1 and decay rate constants (k2) of 7.1 s−1 and 0.2 s−1 for the reactions with unlabeled ACV and AC[d8-V], respectively, from which a D-KIE of at least 30 is calculated (the true, intrinsic D-KIE may be larger if the presence of deuterium results in failed events44). This large D-KIE confirms that the detected Fe(IV) complex cleaves the CVal,β-H bond and provides further confirmation that it is a ferryl complex.

Figure 3.

ΔA515 kinetic traces acquired after mixing of an air–saturated buffer solution (100 mM MOPS pH 7.2; 0.3 mM O2) with an equal volume of a solution containing 3.0 mM IPNS, 3.0 mM Fe(II), 20.0 mM TCEP, and either 20.0 mM ACV (black solid circles) or 20.0 mM AC[d8-V] (red solid circles) at 5 °C. The solid lines are simulations with parameters quoted in the text.

Stopped-flow absorption-spectroscopic evidence for accumulation of the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate

Although the data from experiments with unlabeled ACV and AC[d8-V] provide clear evidence for accumulation of the CVal,β-H-cleaving Fe(IV) complex, there is only a hint of the possible accumulation of any preceding complex, as in the initial Fe(II)-O2 adduct proposed in Scheme 2 to cleave the CCys,β-H bond on the pathway to the Fe(IV)-oxo complex. Therefore, the CCys,β-deuterated substrate (A[d2-C]V) was used as a mechanistic probe, with the expectation that it would enhance accumulation of the CCys,β-H-cleaving complex.44–46 Time-dependent spectra from SF-abs experiments monitoring the reaction of the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V complex with O2 at 5 °C (Figure S12) provide evidence for the anticipated precursor to the ferryl complex. Subtracting spectra from the control experiment lacking O2 to cancel contributions from the protein and contaminants (Figure 4A) yields difference spectra that are markedly different at very early reaction times (red and purple traces) but then evolve at longer reaction times to the signature of the Fe(IV)-oxo complex (green and black traces). The spectrum at 0.0025 s (red trace) deviates markedly from that of the successor complex, exhibiting broad absorption maxima at ~500 nm and ~630 nm. The enhancement of these features by the Cys-labeled substrate implies that they are most likely associated with the CCys,β-H-cleaving complex. The difference spectrum at 0.020 s (blue trace) can be rationalized as a superposition of the spectra of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate and its CCys,β-H-cleaving predecessor, suggesting that, at this reaction time, both intermediates have accumulated. The qualitative similarity of the 0.020-s difference spectrum from the reaction with A[d2-C]V (blue trace) to the 0.0020-s difference spectrum from the reaction with unlabeled ACV (Figure 1A, red line) implies that the same ferryl precursor also accumulates with the unlabeled substrate. At longer times in the reaction with A[d2-C]V, features of the ferryl intermediate come to dominate the spectrum, as in the reaction with unlabeled ACV. A comparison of scaled kinetic traces at 515 nm and 630 nm from the reaction with the cysteine-labeled substrate (Figure 4B) starkly illustrates the accumulation of the 630-nm-absorbing species in advance of the Fe(IV)-oxo complex.

Figure 4.

Stopped-flow absorption data from the reaction of the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V complex with O2. (A) Difference spectra generated by subtracting from experimental spectra acquired 0.002 s (red), 0.007 s (purple), 0.020 s (blue), 0.10 s (green), 0.50 s (black), and 2.0 s (pink) after mixing of a solution containing the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V complex (1.5 mM IPNS, 1.5 mM Fe(II), 0.5 mM ACV in 100 mM MOPS, pH 7.2) with an equal volume of an oxygenated buffer solution (100% O2 at 5 °C, estimated to have 1.8 mM O2) the corresponding spectra from a matched control experiment lacking O2. (B) Comparison of the ΔA515 (red) and ΔA630 (blue) kinetic traces of the reaction with A[d2-C]V. (C) Comparison of the ΔA515 kinetic trace from A (red solid circles) to that of an identical experiment carried out with unlabeled ACV (black solid circles). The solid lines are simulations of the kinetics of absorbance attributable to the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate, with parameters quoted in the text. (D) Simulation of the ΔA515-vs-time traces of the reaction with unlabeled ACV (black) and A[d2-C]V (red) isotopologs. The experimental data is shown as open circles and correspond to the black circles in Figure 3 (ACV) and the red trace of Figure 4B (A[d2-C]V), respectively. The solid black and red lines are simulations of absorbance changes associated with the Fe(III)-superoxo and Fe(IV)-oxo intermediates according to the kinetic model described in Equation (3) using the following parameters: k1 = 153 mM−1s−1, k-1 = 15 s−1, k2 = 973 s−1 (ACV), k2 = 40 s−1 (A[d2-C]V), k3 = 7.1 s−1, and values of Δε515 of 0.67 mM−1cm−1 and 2.7 mM−1cm−1 for the Fe(III)-superoxo and Fe(IV)-oxo intermediates, respectively. The individual contributions from the Fe(III)-superoxo and Fe(IV)-oxo intermediates are shown as dotted and dashed lines, respectively.

Comparison of the ΔA515-vs-time traces from the reaction of the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V complex with O2 (Figure 4C, red open circles) and the corresponding reaction with unlabeled ACV (Figure 4C, black open circles) provides additional evidence for the proposed sequence of intermediates. Because ΔA515 is dominated by the intense absorption from the Fe(IV)-oxo complex, the traces largely reflect formation and decay of this intermediate. The retardation of ferryl formation upon use of A[d2-C]V reflected in this trace provides direct evidence that CCys,β-H-cleavage precedes ferryl formation (and thus also CVal,β-H cleavage) and that the former process exhibits a significant D-KIE.

The simplest explanation for the enhanced accumulation of the 630-nm-absorbing complex with A[d2-C]V is that it is the species that cleaves the CCys,β-H bond. According to this interpretation, protium is abstracted sufficiently rapidly that the responsible intermediate barely accumulates, but the D-KIE is sufficiently large to permit considerably more accumulation of this intermediate species. Analysis of ΔA515-vs-time traces according to the model in Eq. 3 afforded estimates of decay rate constants for the Fe(III)-superoxo complex of (970 ± 240) s−1 and (40 ± 3) s−1 for the reactions with unlabeled ACV and A[d2-C]V, respectively, from which the D-KIE for CCys,β-H cleavage can be estimated to be 17 – 33. We also considered the alternative possibility that (i) the slower cleavage of the CCys,β-D bond results in uncoupling of the reaction and allows formation of an off-pathway complex to compete more effectively with CCys,β-H cleavage and (ii) the transient absorption at ~ 630 nm is largely contributed by this off pathway complex. Analysis of the ΔA515-vs-time trace according to this model (Figure S13) reveals that uncoupling due to the deuterium substitution is, at most, only modest (~20%). While this analysis alone does not provide definitive evidence that the long-wavelength absorption features are associated with the on-pathway (CCys,β-H-cleaving) intermediate, the corresponding FQ-Mössbauer experiments (see below) reveal accumulation of a new intermediate to levels that exceed the maximum flux through the hypothetical uncoupling pathway that could be accommodated by the SF-abs data. Consistent with the interpretation that the long-wavelength features arise from the CCys,β-H-cleaving complex, it has been reported that A[S-d1-C]V is successfully processed to the all-protium IPN product (i.e., the reaction proceeds with abstraction of the pro-S-deuterium), although the product of this reaction was not quantified and the formation of alternative products was not explored.83

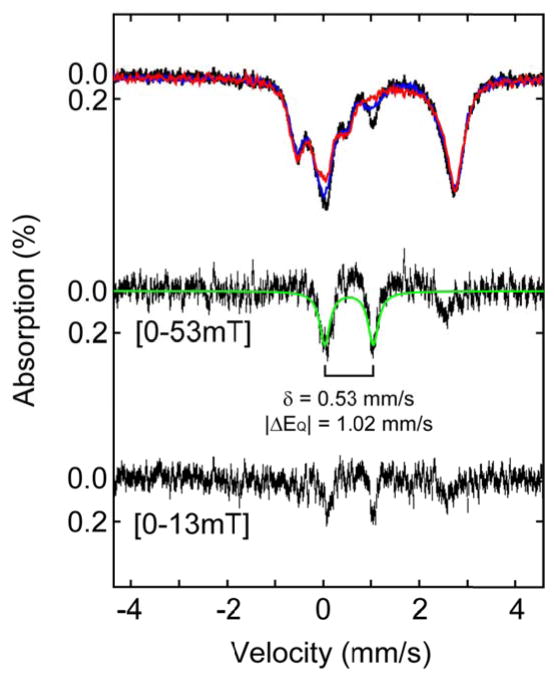

Mössbauer-spectroscopic evidence that the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate is a Fe(III)-superoxo complex

The CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate was further characterized by FQ Mössbauer experiments with A[d2-C]V. Time-dependent, 4.2-K/zero-field Mössbauer spectra of samples prepared by reacting the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V complex with O2 at 5 °C (Figure 5, vertical bars) reveal the presence of a new absorption peak at ~1 mm/s (see arrow) that develops to its maximum intensity by the first accessible reaction time and decays in less than a second. Because this peak develops to a much greater extent with the Cys-deuterated substrate, it is attributable to the 610-nm-absorbing, CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate. The peak is the high-energy line of a quadrupole doublet. Although the low-energy line is not resolved, its position could be determined by two independent approaches.

Figure 5.

Time-dependent 4.2-K/zero-field Mössbauer spectra from the reaction of the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V complex with O2. Spectrum of a solution of the reactant complex (4.5 mM IPNS, 3.6 mM Fe(II), and 20 mM A[d2-C]V in 100 mM MOPS, 10% glycerol at pH 7.2 (A) and spectra of samples prepared by mixing the reactant complex (above) with an oxygen-saturated solution of buffer (at 5 °C, ~1.8 mM O2) in a 1:2 (v/v) ratio and freeze-quenching after reaction times of 0.010 s (B), 0.050 s (D), 0.13 s (E), or 130 s (F) are shown as vertical bars. Spectrum C is the difference spectrum B – A. The solid green, turquoise, red, and blue, lines are quadrupole doublet simulations of the spectra of the IPNS•Fe(II) and IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV complexes and the Fe(IV)-oxo and Fe(III)-superoxo intermediates, respectively, using parameters given in the text. The arrow marks the high-energy line of the spectrum of the Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate.

First, initial subtraction of the spectrum of the reactant control sample gave a difference spectrum that could be analyzed as a superposition of four quadrupole doublets. The parameters of the three quadrupole doublets representing the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V reactant complex (turquoise line), the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate (red line), and the Fe(II)-product complex (gold line) were set to the values determined by the analysis of the Mössbauer spectra with unlabeled ACV substrate (see above), while the parameters of the quadrupole doublet associated with CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate were allowed to vary. This analysis returned parameters for the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate (δ = 0.53 mm/s, |ΔEQ| = 1.02 mm/s, and Γ = 0.29 mm/s; blue line) typical of high-spin Fe(III) complexes with N/O-coordination.49 The fact that the intermediate gives rise to a quadrupole doublet in the absence of applied magnetic field suggests that it has an integer-electron-spin ground state, consistent with expectations and precedent for an Fe(III)-superoxo complex, in which antiferromagnetic (AF) or ferromagnetic (F) exchange coupling between the high-spin Fe(III) (SFe = 5/2) and superoxide radical (SSO = 1/2) would yield an S = 2 or S = 3 total-spin state, respectively.49,76 The time-dependent spectra can be analyzed as the superpositions of the five quadrupole doublets representing the unreactive IPNS•Fe(II) complex, the IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V reactant complex, the IPNS•Fe(II)•IPN product complex, and the Fe(IV)-oxo- and Fe(III)-superoxo-containing intermediate states (black solid lines in Figure 5; see Table S2 for all parameters). Consistent with the SF-abs data, formation of the Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate precedes formation of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate. The complexes contribute 14%, 9%, and ~4% [Fe(III)-superoxo] and 12%, 21%, and 20% [Fe(IV)-oxo] of the total absorption area at reaction times of 0.010, 0.050, and 0.13 s, respectively.

Second, the Mössbauer parameters of the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate were independently determined from spectra of the 0.010-s sample recorded in variable, weak, external magnetic fields (Figure 6). Comparison of spectra recorded in zero-field and in weak applied fields (13 mT or 53 mT) reveals that the spectral features of the Fe(II)-containing complexes and the Fe(IV) intermediate are not (or are only slightly) broadened by the weak applied field. In contrast, the quadrupole doublet associated with the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate exhibits noticeable broadening in the 13-mT spectrum (blue line) and is broadened beyond recognition in the 53-mT spectrum (red line). The field-dependent broadening of the Mössbauer features of the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate can be visualized more clearly in the [0 mT − 53 mT] and [0 mT − 13 mT] difference spectra, in which the downward-pointing doublet represents the spectral features associated with this intermediate in zero-field. (The spectrum of the intermediate with weak applied fields cannot be readily discerned in the difference spectra, because the intermediate contributes only a modest fraction of the overall absorption and its spectrum is broad with an applied field.) Analysis of the difference spectra gives δ = 0.53 mm/s and |ΔEQ| = 1.02 mm/s, green line, identical to the parameters determined by analysis of the 0.010-s spectrum after removal of the contributions of Fe(II) complexes. The observed broadening of the features of the Fe(III)-superoxo complex in weak applied fields gives insight into its electronic structure. The axial ZFS parameter (D) of the S = 2 or S = 3 total-spin state depends primarily on the corresponding parameter of the S = 5/2 Fe site (DFe) and is scaled by spin-projection coefficients DFe = 4/3 (S = 2) or DFe = 2/3 (S = 3).84 Because the values of the dominating component, DFe, are typically small for high-spin Fe(III) complexes, the resulting D of the exchange-coupled system is also expected to be rather small. Consequently, the spin expectation value, 〈S〉, rises steeply with applied field, resulting in the significant internal fields that are responsible for the observed magnetic broadening even with weak applied fields.

Figure 6.

4.2-K/variable-field Mössbauer spectra of a sample prepared by mixing a solution of the reactant complex (4.5 mM IPNS, 3.6 mM Fe(II), and 20 mM A[d2-C]V in 100 mM MOPS, 10% glycerol at pH 7.2) with an oxygen-saturated solution of buffer (at 5 °C, ~1.8 mM O2) in a 1:2 (v/v) ratio and freeze-quenching after reaction times of 0.010 s. (Top) The experimental spectrum collected in zero magnetic field is shown as black vertical bars. The solid blue and red lines are the experimental spectra recorded in an external magnetic field of 13 mT and 53 mT, respectively, (Middle) The (0 – 53mT) difference spectrum is shown as vertical bars. The green line crossing through the difference spectrum is a theoretical simulation using parameters quoted in the main text. (Bottom) The experimental (0 – 13mT) difference spectrum is shown as vertical bars.

Spectra of the 0.010-s sample were also acquired in externally applied magnetic fields of 2 T and 4 T (Figure S14). Owing to the modest fraction of the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate (14%) and the fact that its spectrum splits in an applied field, the outer lines associated with the intermediate could be assigned only tentatively. From the splitting of the outer lines, the magnitude of the A-tensor (assumed to be isotropic for simplicity) could be estimated. Analysis assuming a S = 2 electron ground state yields Aiso,S=2 ≈ −26.2 MHz with respect to the total spin, which corresponds to an intrinsic 57Fe hyperfine coupling of Aiso,57Fe ≈ −22.4 MHz, using the standard spin projection method, Aiso,S=2 = (7/6) Aiso,57Fe.84 Likewise, analysis assuming S = 3 for the total spin ground state yields Aiso,S=3 ≈ −17.9 MHz and Aiso,57Fe ≈ −21.5 MHz, using Aiso,S=3 = (5/6) Aiso,57Fe. Both Aiso,57Fe values are smaller than typical values for N/O-coordinated high-spin Fe(III) (~ −30 MHz),49 but similar values have been reported previously for an inorganic Fe(III)-superoxo complex.85 Although the intrinsic value of A57Fe determined for S = 2 is somewhat more typical, the available data do not allow unambiguous assignment of the spin multiplicity of the ground state. Nevertheless, the Mössbauer data provide strong evidence supporting the formulation of the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate as a Fe(III)-superoxo complex with an S = 2 or S = 3 total-electron-spin ground state.

Evaluation of the intermediates by density functional theory (DFT) calculations

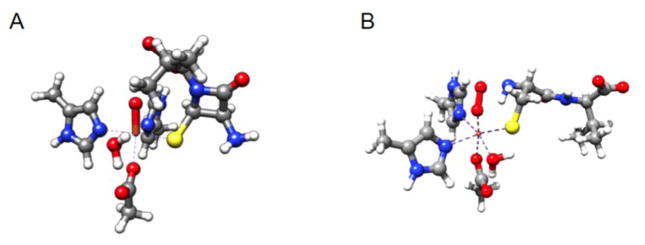

To evaluate the consistency of the structures assigned to the intermediates with their experimentally observed spectroscopic characteristic, we employed DFT calculations on model structures. For the Fe(IV) complex, three models were considered. Model I (Figure 7A) represents intermediate F in the proposed mechanism (Scheme 2), with a closed β-lactam ring. Model II (Figure S15) is based on a proposal advanced in two recent computational studies. It was proposed that, to assist in O-O bond cleavage, the Fe-bound water ligand, rather than the valine N-H bond (step E→F in Scheme 2), may function as a proton donor, thereby leading to formation of a HO-Fe(IV)=O species prior to closure of the β-lactam ring.41,42 Finally, model III has an OH ligand coordinated to the ferryl center with a closed β-lactam ring (Figure S15). The optimized structures for models I and II are in good agreement with those reported by Lundberg, et al.41 These three models all feature a compressed octahedral coordination geometry due to the covalent Fe(IV)-oxo interaction as evidenced by the short Fe-Ooxo bond distances of ~1.64 Å (Table 1). The most significant geometric difference among them is that the Fe-OOH bonds in models II and III are much shorter than the corresponding Fe-OH2O bond in I, reflecting the different Lewis basicity of OH− relative to H2O. Moreover, models II and III have significantly longer Fe-S bonds than that of I.

Figure 7.

Optimized geometric structures of model I of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate (left) and model VI of the Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate (right).

Of the spin-Hamiltonian parameters that can be calculated, isomer shifts typically have the greatest accuracy, with uncertainties less than 0.1 mm/s.63,66 For the three models interrogated, only for model I does the computed isomer shift agree with the experimental value within this established accuracy, whereas those for models II and III are well outside this error range.66 Models II and III can thus be ruled out as models for the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate. The significantly diminished isomer shifts computed for models II and III likely arise from the short Fe-OH bonds, because the isomer shift correlates not only with the dn configuration of the iron center but also with the metal-ligand distances.63,86 The calculated quadrupole splitting and magnetic-hyperfine splitting for model I also match the experiment within the accepted uncertainty (~ 0.5 mm/s for quadrupole splittings and ~ 3 MHz for hyperfine splittings).67 The magnitude of the anisotropy of the hyperfine tensor in the xy plane calculated for I (|Ax−Ay| = 6.4 MHz) is comparable to the experimental value (|Ax−Ay| = 5.9 MHz). The significant underestimation of ZFS parameters for high-spin ferryl complexes has been observed in prior work87 and stems largely from the intrinsically poor ability of DFT calculations to correctly predict spin-state energetics for transition metal complexes.88 As analyzed elsewhere,89–91 the predominant contributor to the ZFS parameter of an S = 2 ferryl unit is the extremely low-lying triplet excited state. To reach quantitative agreement, one has to resort to more advanced ab initio approaches.92

For the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate, we considered interaction of a triplet O2 with a high-spin Fe(II) to yield three possible total spin states (S = 1, 2, and 3) for the O2 adduct (Figure 7B and S14). In addition, two different binding modes of O2, namely end-on and side-on, were evaluated (Figure S14). The triplet side-on species was not located, because, in the course of the geometry optimization, the O2 motif was seen invariably to rearrange to the end-on mode, as found in an earlier computational study.40 The calculated key structural parameters (Table 2) are in reasonable agreement with those reported in earlier work,40,41,93 although different computational procedures were employed there. The estimated marginal energy gaps between different spin states definitely fall within the computational uncertainty of DFT methods,88 and hence prevent further discrimination.40,94 A similar situation was encountered in previous work examining possible structures of initial O2 adducts in TauD95 and HPCD.96 By contrast, spectroscopic parameters are usually much more sensitive to small geometric changes and thus provide a more reliable probe for the electronic structure.96 Indeed, the computed isomer shift agrees with the experimental value only for model VI, whereas those for the other models are greater than the observed isomer shift by at least 0.17 mm/s (Table 2). In addition, the calculations on model VI also yield both a quadrupole-splitting parameter similar to the experimental value and a nearly isotropic hyperfine-coupling tensor. Moreover, the computationally predicted Aiso–value for model VI matches that determined experimentally within the computational uncertainty (~ 3 MHz).67 Thus, model VI is a consistent model for the CCys,β-H-cleaving intermediate. As shown in the molecular orbital (MO) diagram of model VI (Figure S16), the upper valence region has six singly occupied MOs, of which five are Fe-3d based and the last one is O2-π* centered. As the electron residing in the O2-π* MO has spin opposite to that on the Fe center, this intermediate is best formulated as a high-spin ferric center (SFe = 5/2) that is AF coupled to a superoxo radical ligand (SSO = 1/2), in line with the electronic-structural description deduced by Mössbauer spectroscopy.#

Table 2.

Key structural parameters and calculated spin Hamiltonian parameters for the models of the Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate.

| IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | experimental | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spin | S = 3 | S = 3 | S = 2 | S = 2 | S = 1 | |

| ΔE (kcal/mol) | 0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 2.1 | |

| Fe-O | 2.042 | 2.162 | 1.833 | 2.202 | 2.059 | |

| Fe-O | 3.197 | 2.186 | 2.930 | 2.156 | 2.892 | |

| O-O | 1.313 | 1.329 | 1.323 | 1.307 | 1.253 | |

| δ (mm/s) | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.53 |

| ΔEQ (mm/s) | −0.63 | 0.62 | 1.12 | 0.66 | 3.50 | 1.02 |

| η | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| A (MHz) | −23.8 −24.8 −26.2 |

−24.0 −24.9 −26.4 |

−27.6 −29.4 −31.2 |

−31.7 −33.4 −35.4 |

−26.2 −26.8 −28.8 |

DISCUSSION

The Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate and its role in β-lactam ring closure

The first intermediate of the IPNS catalytic cycle, which accumulates after the addition of O2 to the reactant complex, is the CCys,β-H-cleaving complex (C in Scheme 2). This intermediate accumulates to modest levels (~14%) in the presence of selectively deuterated A[d2-C]V substrate. When the reaction is carried out with unlabeled ACV substrate, this intermediate’s SF-abs signatures are barely detectable at very early reaction times, and, by the first reaction time accessible by conventional freeze-quench methodology (~ 10 ms), the intermediate escapes under the detection limit of Mössbauer spectroscopy (< 3%). The greater accumulation with the A[d2-C]V substrate presumably results form a D-KIE on cleavage of the CCys,β-H bond and therefore provides direct evidence that the intermediate is the CCys,β-H-cleaving complex. The intermediate exhibits Mössbauer parameters consistent with a high-spin Fe(III)-superoxo species and broad absorption features in the SF-abs spectra centered at ~630 nm and ~500 nm.

Fe(III)-superoxo species have been proposed as key early intermediates in virtually all MNH-Fe( II) enzymes.20,21,24,25,45,46 However, they generally do not accumulate to levels allowing their identification or comprehensive spectroscopic and structural characterization. To our knowledge, two spectroscopically characterized MNH high-spin Fe(III)-superoxo complexes have been reported to date. Only one of these was detected in an enzyme, specifically in the H200N variant of the MNH-Fe(II) enzyme HPCD.97 An Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate is proposed as an intermediate of the native HPCD reaction cycle, but it is too reactive to be trapped. The combined use of a variant that perturbs the H-bonding network (H200N) and of an analog with an electron-withdrawing group (4-nitrocatechol) led to accumulation of the cognate intermediate to a high level (80 %). A combination of Mössbauer and parallel-mode EPR spectroscopies, coupled to DFT calculations, revealed that the electronic structure of this complex is best described as a high-spin Fe(III) site that is AF coupled to a superoxide radical anion, yielding a S = 2 electron-spin ground state.97 The intermediate exhibits parallel-mode EPR features at g = 8.17, 8.8, and 11.6 and gives rise to both a Mössbauer quadrupole doublet in zero field (δ = 0.50 mm/s and ΔEQ = −0.33 mm/s) and magnetically split Mössbauer spectra in externally applied magnetic fields. The Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate of H200N HPCD also exhibits an absorption band at 610 nm, close to the energy of the absorption feature at 630 nm observed for the IPNS Fe(III)-superoxo. The similarity of the spectroscopic properties of the IPNS intermediate to those of the complex in HPCD-H200N is additional support for the assignment of the IPNS complex as an Fe(III)-superoxo complex.

The second Fe(III)-superoxo complex is a recently reported inorganic model complex with the pentadentate ligand 2,6-bis-(((S)-2-(diphenylhydroxymethyl)-1-pyrrolidinyl)-methyl)-pyridine (H2BDPP).85 The reaction of [Fe(II)BDPP] with O2 at −80 °C yielded the Fe(III)-superoxo complex, [Fe(III)BDPP(O2−•)], which has spectroscopic properties distinct from those of the cognate enzyme intermediates. [Fe(III)BDPP(O2−•)] exhibits a magnetically split Mössbauer spectrum even in the absence of an applied field as a consequence of its unique electronic structure with two nearly degenerate (ΔE < 0.003 cm−1) electronic ground states. The total electron-spin ground state of [Fe(III)BDPP(O2−•)] has yet to be conclusively determined but can be plausibly explained by S = 3.85

The reactivity of the IPNS Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate is similar to that of the dinuclear Fe2(III/III)-superoxo intermediate, termed G, of myo-inositol oxygenase (MIOX), despite the fact that the two enzymes differ in the nuclearities of their metallocofactors.98,99 Like the IPNS Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate, G is formed by oxidative addition of O2 to the Fe(II) site of the Fe2(II/III) cofactor of MIOX, and it also cleaves an aliphatic C-H bond, the C1-H bond of the myo-inositol (cyclohexan-1,2,3,5/4,6-hexa-ol, MI) substrate. In the MIOX•MI complex, the C1-bonded oxygen of MI coordinates to the Fe(III) site of the cofactor,100 just as the cysteinyl sulfur of ACV coordinates to the Fe(II) cofactor in IPNS.38 Thus, for both enzymes, the C-H bond to be cleaved is activated by coordination (presumably with deprotonation) of an α-heteroatom.45 The C-H(D) cleavage step effected by G of MIOX exhibits a moderate D-KIE estimated to be 8–16.98 The determination of the D-KIE in MIOX was complicated by the fact that (i) formation of G is reversible and (ii) it does not accumulate to appreciable levels with the unlabeled substrate and accumulates only to modest levels with the deuterium-labeled substrate.98 The same challenges exist for determination of the D-KIE in the IPNS C–H-cleavage step. Nevertheless, a lower limit of 17 can be estimated from analyzing the time-dependent absorption changes at 515 nm of the reactions with unlabeled ACV and A[d2-C]V.

Steps following C-H cleavage may also be similar in IPNS and MIOX. For IPNS, it is thought that the thioketyl radical intermediate undergoes an inner-sphere electron transfer to the Fe(III) center to form a hydroperoxo-Fe(II)/thioaldehyde complex (D→E), which is nucleophilically attacked by the deprotonated valine amide nitrogen to form the β lactam ring (E→F). Similarly, one of the proposed pathways for formation of MI in MIOX involves an inner-sphere electron transfer from the C1-ketyl radical intermediate to the Fe2(III/III) cofactor to yield a hydroperoxo-Fe2(II/III)-myo-inosose-1 intermediate (myo-inosose-1 is the C1-ketone of MI), which may undergo attack of the peroxide on the C1 carbonyl to initiate C1–C6 cleavage and generate the product, D-glucuronate.

The Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate and its role in thiazolidine ring formation

The second C-H-cleaving intermediate of IPNS is a high-spin Fe(IV) complex, presumably the high-spin ferryl species, F, in Scheme 2. It cleaves the CVal,β-H-bond of the monocyclic β-lactam intermediate. The intermediate exhibits Mössbauer parameters typical of high-spin ferryl complexes trapped in other MNH-Fe(II) enzymes,47,78,80–82,101,102 including an isomer shift of ~0.3 mm/s, a small negative quadrupole splitting parameter, and a positive axial ZFS parameter of ~ 10 cm−1.89 However, compared to other high-spin ferryl complexes, the anisotropy of the internal magnetic field in the xy plane (i.e. the plane perpendicular to the ferryl moiety) is more pronounced, due to both a more pronounced rhombicity (E/D = 0.09) and a less axial hyperfine tensor (|Ax| − |Ay| = 6 MHz). The anisotropy of the hyperfine tensor features are well reproduced computationally. Another feature unique to the IPNS ferryl intermediate is its absorption bands, which are tentatively assigned to sulfur-to-iron charge transfer transitions.

The oxidation initiated by the ferryl intermediate of IPNS is reminiscent of that in the Fe(II)-and 2OG-dependent halogenases.103 These enzymes use a cis-halo-ferryl intermediate to cleave an unactivated, aliphatic C-H bond by H-atom abstraction, yielding a putative cis-halo-Fe(III)-OH/substrate radical state. Attack of the substrate radical on the halide ligand coordinated cis to the hydroxide group yields the halogenated product and a coordinatively unsaturated Fe(II) site.78,81,82,101 Likewise, in IPNS, the ferryl abstracts an unactivated H-atom (F→G), and the resulting substrate radical attacks the cis-coordinated sulfur (G→H), yielding a Fe(II) site and the IPN product, which coordinates the Fe(II) center via its thioether sulfur.39 For the halogenase SyrB2, it was shown that the position of the C-H bond to be cleaved relative to the ferryl moiety is the key factor resulting in the alternative outcome (halogenation rather than hydroxylation). Specifically, in SyrB2 the target C-H bond is positioned further away and in the equatorial plane, thereby decreasing C-H cleavage efficiency and disfavoring subsequent attack of the radical upon the hydroxo ligand.82,104 The diminished C-H cleavage efficiency is evident in the decay rate constants of the ferryl, which are less by 102–103 in the halogenase SyrB2 (0.07 s−1 at 5 °C in the presence of the native, unlabeled substrate82) than in related hydroxylases [13 s−1 and ~300 s−1 (both at 5°C) for TauD and the prolyl-4-hydroxylase from Paramecium bursaria Chlorella virus I, each acting on protium-containing substrate79,80]. Consistent with this trend, decay of the ferryl complex in IPNS is slower (kdecay = 6 s−1 at 5 °C with unlabeled ACV) than the corresponding C-H cleavage steps in the hydroxylases, but also significantly faster than C-H cleavage by the halogenases. Hydrogen abstraction by the ferryl in IPNS exhibits a D-KIE of ≥ 30 (kdecay = 0.2 s−1 at 5 °C with AC[d8-V]). We note that while it is possible to determine the decay rate constants with both isotopologs with good precision, the determination of the D-KIE requires quantitatively accounting for potential unproductive reaction pathways,44 which we have not yet investigated in IPNS.

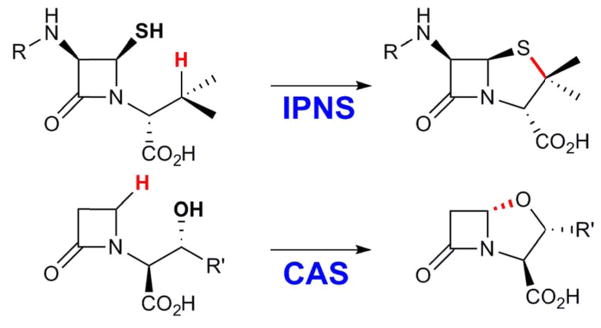

Thiazolidine ring formation in IPNS has evident analogy to formation of the oxazolidine ring in the biosynthesis of the important antibiotic, clavulanic acid, which is catalyzed by the enzyme clavaminate synthase (CAS) (Scheme 3).105,106 CAS is an Fe(II)- and 2OG-dependent enzyme and catalyzes three distinct reactions (hydroxylation, desaturation, and formation of the oxazolidine ring) in the biosynthesis of clavulanic acid. The thiazolidine and oxazolidine-generating reactions are both 1,5-dehydrogenations and involve, formally, removal of hydrogen atoms from both an aliphatic carbon and the heteroatom (X = S, O) to be incorporated in the ring and formation of the new C-X bond. Both reactions are two-electron oxidations and are effected by a ferryl intermediate, although the nature of the two-electron oxidation required for ferryl generation from the Fe(II) cofactor with O2 is different in the two enzymes, [Fe(III)-superoxo-mediated β-lactam-ring formation in IPNS vs decarboxylation of the co-substrate 2OG in CAS].

Scheme 3.

Comparison of the thiazolidine and oxazolidine ring formation reactions mediated by the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediates of IPNS and clavaminate synthase (CAS).

However, there is an important difference between the two reactions. The IPNS reaction involves attack of the substrate radical on an atom directly coordinated to the Fe center (sulfur from the β-lactam intermediate in IPNS). In the case of CAS, there is no obvious open coordination site for the substrate to bind via the O-atom that is incorporated into the oxazolidine ring. Indeed, magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectroscopic studies on CAS revealed an octahedral coordination environment of Fe in the CAS•Fe(II)•2OG complex, which consists of the “His2(Asp/Glu) facial triad,” the bidentate co-substrate, 2OG, and a water molecule.107 Addition of the substrate results in dissociation of the water ligand, thereby creating the necessary open coordination site for O2 to bind.107 Similar experiments on other Fe(II)/2OG enzymes108 have shown that the generation of an coordinatively unsaturated Fe(II) primed for reaction with O2 is a general feature of this enzyme family.20 Thus, the substrate does not bind directly to the Fe center. An alternative mechanism has been proposed on the basis of a computational study for oxazolidine ring formation by CAS. Ring closure is initiated by abstraction of the hydrogen atom from the O-H group of the substrate by the ferryl.109 Indeed, the x-ray crystal structure of the CAS•Fe(II)•2OG•proclavaminate complex reveals that the O-atom that is incorporated into the thiazolidine ring is positioned only 4.2 Å from the Fe,110 suggesting that O-H cleavage by the ferryl intermediate may indeed be possible.111 Ongoing efforts in our group are aimed at unraveling the mechanistic diversity of ferryl-mediated functionalization of unactivated carbon centers in greater depth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM-69657 to CK and JMB), the National Science Foundation (MCB-642058 and CHE-724084 to CK and JMB), the American Chemical Society, Petroleum Research Fund (47214-AC3 to CK and JMB), the German Science Foundation (DFG NE 690/7-1 to SY and FN), the University of Bonn (SY and FN), and the Max-Planck Society (SY and FN). We thank Prof. Christopher J. Schofield (Oxford University) for providing us with plasmid pJB703 containing the gene encoding Aspergillus nidulans isopenicillin N synthase.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 2OG

2-(oxo)glutarate

- ACV

δ-(L-α-aminoadipoyl)-L-cysteinyl-D-valine

- DFT

density functional theory

- D-KIE

deuterium kinetic isotope effect

- EFG

electric field gradient

- FQ

freeze-quench

- HPCD

homoprotocatechuate-2,3-dioxygenase

- IPN

isopenicillin N

- IPNS

isopenicillin N synthase

- LC/MS

liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- MI

myo-inositol (cyclohexan-1,2,3,5/4,6-hexa-ol)

- MIOX

myo-inositol oxygenase

- MNH

mononuclear non-heme

- PDA

photodiode array

- PMT

photomultiplier tube

- SF-abs

stopped-flow absorption

- TauD

taurine:2-oxo-glutarate dioxygenase

- ZFS

zero-field splitting

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Materials; Sequence of plasmid pIPNS; Procedures for over-expression and purification of IPNS; Procedure for synthesis of AC[d8-V]; LC/MS data demonstrating the IPNS-catalyzed conversion of ACV to IPN; 1H-NMR spectra of AC[d8-V] and intermediates depicted in Scheme S1; raw SF-abs data from the reaction of O2 with either IPNS•Fe(II)•ACV or IPNS•Fe(II)•A[d2-C]V; comparison of SF-abs and FQ-Mössbauer features of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate and analysis of the Mössbauer spectra of this experiment; 4.2-K/variable-field Mössbauer spectra of the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate and simulation thereof; 4.2-K/high-field Mössbauer spectra of a sample containing the Fe(III)-superoxo intermediate; depictions of model structures for the intermediates generated by DFT; orbital scheme of model VI of the Fe(III)-superoxo generated by DFT; relative quantities of the relevant species obtained from analysis of the 4.2-K/zero-field Mössbauer time courses. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Fleming A. Brit J Exp Pathol. 1929;10:226. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham EP, Gardner AD, Chain E, Heatley NG, Fletcher CM, Jennings MA. Lancet. 1941;2:177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chain E, Florey HW, Gardner AD, Heatley NG, Jennings MA, Ewing JO, Sanders AG. Lancet. 1940;2:226. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyons C. J Am Med Assoc. 1943;123:1007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tipper DJ, Stroming Jl. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 1965;54:1133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.4.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham EP, Chain E. Nature. 1940;146:837. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livermore DM. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reading C, Cole M. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1977;11:852. doi: 10.1128/aac.11.5.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kershaw NJ, Caines MEC, Sleeman MC, Schofield CJ. Chem Comm. 2005:4251. doi: 10.1039/b505964j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnstein HRV, Morris D. Biochem J. 1960;76:357. doi: 10.1042/bj0760357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loder PB, Abraham EP. Biochem J. 1971;123:471. doi: 10.1042/bj1230471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fawcett PA, Abraham EP. Methods in Enzymology. 1975;43:471. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)43105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Liempt H, von Döhren H, Kleinkauf H. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez S, Diez B, Montenegro E, Martin JF. J Bact. 1991;173:2354. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2354-2365.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byford MF, Baldwin JE, Shiau CY, Schofield CJ. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2631. doi: 10.1021/cr960018l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samson SM, Belagaje R, Blankenship DT, Chapman JL, Perry D, Skatrud PL, VanFrank RM, Abraham EP, Baldwin JE, Queener SW, Ingolia TD. Nature. 1985;318:191. doi: 10.1038/318191a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldwin JE, Abraham E. Nat Prod Rep. 1988;5:129. doi: 10.1039/np9880500129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldwin JE, Bradley M. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1079. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin JE, Schofield CJ. In: The chemistry of β-lactams. Page MI, editor. Blackie; London: 1991. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon EI, Brunold TC, Davis MI, Kemsley JN, Lee SK, Lehnert N, Neese F, Skulan AJ, Yang YS, Zhou J. Chem Rev. 2000;100:235. doi: 10.1021/cr9900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr Chem Rev. 2004;104:939. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abu-Omar MM, Loaiza A, Hontzeas N. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2227. doi: 10.1021/cr040653o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovaleva EG, Neibergall MB, Chakrabarty S, Lipscomb JD. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:475. doi: 10.1021/ar700052v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krebs C, Galonić Fujimori D, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM., Jr Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:484. doi: 10.1021/ar700066p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hausinger RP. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:21. doi: 10.1080/10409230490440541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14083. doi: 10.1021/bi035656u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibson DT, Parales RE. Curr Opin Biotechnology. 2000;11:236. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bugg TDH, Lin G. Chem Comm. 2001:941. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straganz GD, Glieder A, Brecker L, Ribbons DW, Steiner W. Biochem J. 2003;369:573. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoy JG, Bailey LJ, Bitto E, Bingman CA, Aceti DJ, Fox BG, Phillips GN. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2006;103:3084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509262103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph CA, Maroney MJ. Chem Comm. 2007:3338. doi: 10.1039/b702158e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neidig ML, Decker A, Choroba OW, Huang F, Kavana M, Moran GR, Spencer JB, Solomon EI. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2006;103:12966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605067103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pojer F, Kahlich R, Kammerer B, Li SM, Heide L. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cicchillo RM, Zhang HJ, Blodgett JAV, Whitteck JT, Li GY, Nair SK, van der Donk WA, Metcalf WW. Nature. 2009;459:871. doi: 10.1038/nature07972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metcalf WW, Griffin BM, Cicchillo RM, Gao JT, Janga SC, Cooke HA, Circello BT, Evans BS, Martens-Habbena W, Stahl DA, van der Donk WA. Science. 2012;337:1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1219875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roach PL, Clifton IJ, Fulop V, Harlos K, Barton GJ, Hajdu J, Andersson I, Schofield CJ, Baldwin JE. Nature. 1995;375:700. doi: 10.1038/375700a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roach PL, Clifton IJ, Hensgens CMH, Shibata N, Long AJ, Strange RW, Hasnain SS, Schofield CJ, Baldwin JE, Hajdu J. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:736. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0736r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roach PL, Clifton IJ, Hensgens CMH, Shibta N, Schofield CJ, Hajdu J, Baldwin JE. Nature. 1997;387:827. doi: 10.1038/42990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burzlaff NI, Rutledge PJ, Clifton LJ, Hensgens CMH, Pickford M, Adlington RM, Roach PL, Baldwin JE. Nature. 1999;401:721. doi: 10.1038/44400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lundberg M, Morokuma K. J Phys Chem, B. 2007;111:9380. doi: 10.1021/jp071878g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundberg M, Siegbahn PEM, Morokuma K. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1031. doi: 10.1021/bi701577q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundberg M, Kawatsu T, Vreven T, Frisch MJ, Morokuma K. J Chem Theo Comp. 2009;5:222. doi: 10.1021/ct800457g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown-Marshall CD, Diebold AR, Solomon EI. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1176. doi: 10.1021/bi901772w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:586. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bollinger JM, Krebs C. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:151. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Donk WA, Krebs C, Bollinger JM. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:673. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price JC, Barr EW, Tirupati B, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7497. doi: 10.1021/bi030011f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamanaha EY. PhD Thesis. The Pennsylvania State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Münck E. In: Physical Methods in Bioinorganic Chemistry. Que L Jr, editor. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA: 2000. p. 287. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee CT, Yang WT, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grimme S. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:1787. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG. J Chem Phys. 1993;99:4597. [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG. J Chem Phys. 1994;101:9783. [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Lenthe E, van Leeuwen R, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG. Int J Quantum Chem. 1996;57:281. [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Wüllen C. J Chem Phys. 1998;109:392. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pantazis DA, Chen XY, Landis CR, Neese F. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:908. doi: 10.1021/ct800047t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pantazis DA, Neese F. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;5:2229. doi: 10.1021/ct900090f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neese F, Wennmohs F, Hansen A, Becker U. Chem Phys Lett. 2009;356:98. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eichkorn K, Treutler O, Öhm H, Häser M, Ahlrichs R. Chem Phys Lett. 1995;240:283. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klamt A, Schüürmann G. J Chem Soc-Perkin Trans 2. 1993;799 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siegbahn PEM. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:695. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neese F. Inorg Chim Acta. 2002;337:181. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schäfer A, Huber C, Ahlrichs R. J Chem Phys. 1994;100:5829. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schäfer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. J Chem Phys. 1992;97:2571. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Römelt M, Ye SF, Neese F. Inorganic Chemistry. 2009;48:784. doi: 10.1021/ic801535v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sinnecker S, Slep LD, Bill E, Neese F. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:2245. doi: 10.1021/ic048609e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neese F. J Chem Phys. 2003;118:3939. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sinnecker S, Neese F, Noodleman L, Lubitz W. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2613. doi: 10.1021/ja0390202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neese F. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:164112. doi: 10.1063/1.2772857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McWeeny R, Mizuno Y. Proc Royal Soc London. 1961;259:554. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sinnecker S, Neese F. J Chem Phys A. 2006;110:12267. doi: 10.1021/jp0643303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Neese F. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Computational Molecular Science. 2012;2:73. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.An alternative solution with k1 = 7 s−1 and k2 = 125 s−1 is mathematically equivalent but predicts much less accumulation of the intermediate and would require a much greater molar absorptivity for it; Mössbauer-spectroscopic experiments and SF-abs-spectroscopic experiments with the AC[d8-V] analog described below rule out this alternative solution..

- 75.Gütlich P, Link R, Trautwein AX. Mössbauer Spectroscopy and Transition Metal Chemistry. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krebs C, Price JC, Baldwin J, Saleh L, Green MT, Bollinger JM., Jr Inorg Chem. 2005;44:742. doi: 10.1021/ic048523l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Orville AM, Chen VJ, Kriauciunas A, Harpel MR, Fox BG, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4602. doi: 10.1021/bi00134a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Matthews ML, Krest CM, Barr EW, Vaillancourt FH, Walsh CT, Green MT, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr Biochemistry. 2009;48:4331. doi: 10.1021/bi900109z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Price JC, Barr EW, Glass TE, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13008. doi: 10.1021/ja037400h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoffart LM, Barr EW, Guyer RB, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2006;103:14738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604005103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Galonić DP, Barr EW, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. Nature Chem Biol. 2007;3:113. doi: 10.1038/nchembio856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matthews ML, Neumann CS, Miles LA, Grove TL, Booker SJ, Krebs C, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2009;106:17723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909649106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baldwin JE, Adlington RM, Robinson NG, Ting HH. J Chem Soc Chem Comm. 1986:409. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bencini A, Gatteschi D. EPR of Exchange Coupled Systems. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chiang CW, Kleespies ST, Stout HD, Meier KK, Li PY, Bominaar EL, Que L, Jr, Münck E, Lee WZ. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10846. doi: 10.1021/ja504410s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ye S, Bill E, Neese F. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:3468. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sinnecker S, Svensen N, Barr EW, Ye S, Bollinger JM, Jr, Neese F, Krebs C. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6168. doi: 10.1021/ja067899q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ye S, Neese F. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:772. doi: 10.1021/ic902365a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Neese F. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:716. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bukowski MR, Koehntop KD, Stubna A, Bominaar EL, Halfen JA, Münck E, Nam W, Que L., Jr Science. 2005;310:1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1119092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chanda A, Shan XP, Chakrabarti M, Ellis WC, Popescu DL, de Oliveira FT, Wang D, Que L, Collins TJ, Münck E, Bominaar EL. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:3669. doi: 10.1021/ic7022902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ye S, Xue G, Krivokapic I, Petrenko T, Bill E, Que L, Jr, Neese F. Chem Sci. 2015;6:2909. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03268c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brown CD, Neidig ML, Neibergall MB, Lipscomb JD, Solomon EI. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:7427. doi: 10.1021/ja071364v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Diebold AR, Neidig ML, Moran GR, Straganz GD, Solomon EI. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6945. doi: 10.1021/bi100892w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ye SF, Riplinger C, Hansen A, Krebs C, Bollinger JM, Neese F. Chemistry - a European Journal. 2012;18:6555. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Christian GJ, Ye SF, Neese F. Chemical Science. 2012;3:1600. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mbughuni MM, Chakrabarti M, Hayden JA, Bominaar EL, Hendrich MP, Münck E, Lipscomb JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2010;107:16788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xing G, Diao Y, Hoffart LM, Barr EW, Prabhu KS, Arner RJ, Reddy CC, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2006;103:6130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508473103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bollinger JM, Jr, Diao Y, Matthews ML, Xing G, Krebs C. Dalton Trans. 2009;6:905. doi: 10.1039/b811885j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brown PM, Caradoc-Davies TT, Dickson JMJ, Cooper GJS, Loomes KM, Baker EN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605143103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Galonić Fujimori D, Barr EW, Matthews ML, Koch GM, Yonce JR, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C, Riggs-Gelasco PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13408. doi: 10.1021/ja076454e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Eser BE, Barr EW, Frantom PA, Saleh L, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C, Fitzpatrick PF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11334. doi: 10.1021/ja074446s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Walsh CT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3364. doi: 10.1021/cr050313i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Martinie RJ, Livada J, Chang W-c, Green MT, Krebs C, Bollinger JM, Jr, Silakov A. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6912. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Salowe SP, Marsh EN, Townsend CA. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6499. doi: 10.1021/bi00479a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Salowe SP, Krol WJ, Iwata-Reuyl D, Townsend CA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2281. doi: 10.1021/bi00222a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pavel EG, Zhou J, Busby RW, Gunsior M, Townsend CA, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:743. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Neidig ML, Brown CD, Light KM, Fujimori DG, Nolan EM, Price JC, Barr EW, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C, Walsh CT, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14224. doi: 10.1021/ja074557r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Borowski T, de Marothy S, Broclawik E, Schofield CJ, Siegbahn PEM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3682. doi: 10.1021/bi602458m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]