Abstract

Purpose

To explore the sentiment and themes of Twitter chatter that mentions both alcohol and marijuana.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of tweets mentioning both alcohol and marijuana during 1 month was performed.

Setting

The study setting was Twitter.

Participants

Tweets sent from February 4 to March 5, 2014, were studied.

Method

A random sample (n = 5000) of tweets that mentioned alcohol and marijuana were qualitatively coded as normalizing both substances, preferring one substance over the other, or discouraging both substances. Other common themes were identified.

Results

More than half (54%) of the tweets normalized marijuana and alcohol (without preferring one substance over the other), and 24% preferred marijuana over alcohol. Only 2% expressed a preference for alcohol over marijuana, 7% discouraged the use of both substances, and the sentiment was unknown for 13% of the tweets. Common themes among tweets that normalized both substances included using the substances with friends (17%) and mentioning substance use in the context of sex or romance (14%). Common themes among tweets that preferred marijuana over alcohol were the beliefs that marijuana is safer than alcohol (46%) and preferences for effects of marijuana over alcohol (40%).

Conclusion

Tweets normalizing polysubstance use or encouraging marijuana use over alcohol use are common. Both online and offline prevention efforts are needed to increase awareness of the risks associated with polysubstance use and marijuana use.

Keywords: Social Media, Alcohol, Marijuana, Twitter, Prevention Research

PURPOSE

In recent years, perceived risk and use of both marijuana and alcohol have shifted among youth and young adults in the United States. The percent of adolescents who believe that smoking marijuana regularly (once or twice a week) is of great harm decreased from 54.6% in 2007 to 39.5% in 2013.1 Past month use of marijuana increased from 6.7% in 2007 to 7.9% in 2011, and then decreased slightly to 7.1% in 2013.1 Likewise, among young adults ages 18 to 25 years, rates of past month marijuana use in 2009–2013 ranged from 18.2% to 19.1%, which is higher than past rates of use (2002–2008 range, 16.1%–17.3%).1 In contrast, perceptions of great harm associated with binge drinking (5 or more drinks on the same occasion) once or twice a week have increased among adolescents in the past decade (from 38.2% in 2002 to 40.7% in 2011, then dropping slightly to 39.0% in 2013), and past month binge drinking has declined from 10.7% in 2002 to 6.2% in 2013.1 Past month binge drinking among young adult men was lower in 2013 (44.4%) than in 2002–2010 (range, 48.1%–51.7%).1 Even with the decreases in binge drinking during the past decade, rates are as high as or higher than marijuana use.

Social norms, peer influences, and media are among the most important factors having an impact on risky substance use attitudes and behaviors of young people.2–10 Social media has become increasingly popular among young people and combines both media and peer influences from a network of individuals across a wide range of geographic regions; thus, the impact on social norms, risk perceptions, and behaviors among youth could be substantial. Young people commonly communicate their substance use attitudes and behaviors on social media.11–13 For example, one-third of a sample of college students had posted a picture showing themselves drinking on a social networking site, and 83% said a friend had posted such pictures.14 It is also common for young people to “follow” social media profiles (i.e., automatically receive updates and posts from specific profiles) that promote substance use behaviors. For instance, we identified a popular Twitter account with a marijuana-focused handle (i.e., user name) that tweeted primarily promarijuana messages and had more than 1 million followers, most of whom were youth and young adults.15

Exposure to pictures of friends drinking or portraying alcohol use as normative on social network sites has also been associated with alcohol use and proalcohol perceptions. In a study of nearly 200 young adolescents ages 13 to 15 years, those who viewed Facebook profiles that normalized alcohol use among older peers had higher levels of risk-promoting cognitions (e.g., more willingness to drink, increased proalcohol use attitudes) than those who saw profiles of older peers that did not normalize drinking.16 Similarly, 10th-grade students who viewed pictures of friends on social networking sites that displayed partying or drinking were themselves more likely to smoke cigarettes and use alcohol.17

In light of changing attitudes about marijuana and alcohol, and the high prevalence of their use, we extend prior research on the communication of substance use on social media by focusing on posts that mention both alcohol and marijuana. We analyzed Twitter because it is one of the most popular social networking sites, especially among teens and young adults.18,19 We sought to better understand the sentiment of tweets that reference both marijuana and alcohol together in the same tweet, and to identify their most common themes. Given the recent decrease in risk perceptions about marijuana and increase in risk perceptions about binge drinking, as well as the rather high prevalence of use for both substances, we hypothesized that a preference for marijuana over alcohol would be common and that many tweets would normalize both of the substances.

DESIGN

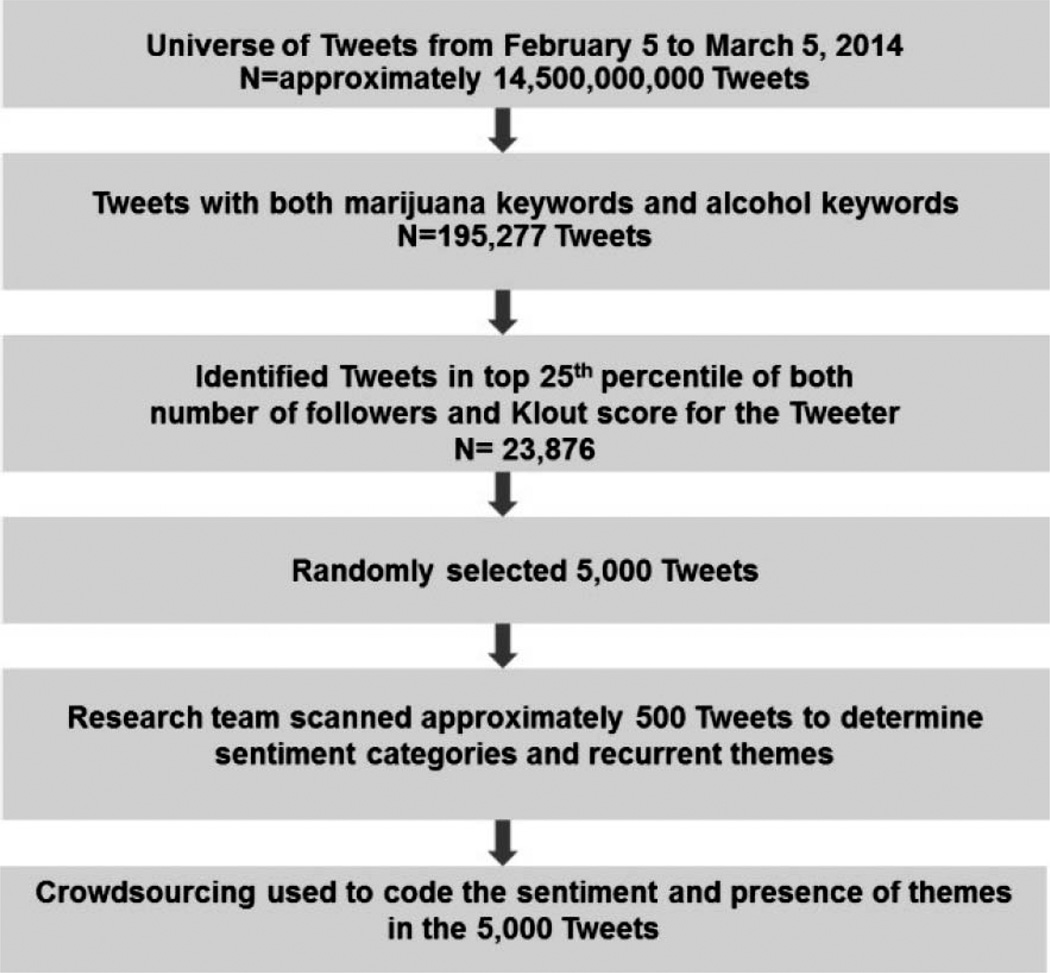

This study is cross-sectional in nature because we examined Twitter data gathered during approximately 1 month to examine tweets that mentioned both alcohol and marijuana. Our research received an Institutional Review Board exemption (i.e., is exempt from Institutional Review Board oversight) because the Twitter data in the current study are publicly available existing data with minimal risk. Figure 1 depicts the flow of the study methodology.

Figure 1.

Flow of Study Methodology

Setting

The setting of the study was the social media site Twitter.

Participants

Tweets were the unit of analysis in our study. Tweets in the English language that mentioned both alcohol and marijuana were collected from February 5 to March 5, 2014.

METHOD

Data Collection

Marijuana-related tweets for the time period of interest were collected using Simply Measured (http://simplymeasured.com), a company that provides social media analytics and has access to the full stream of tweets. Tweets with at least one of the following terms (or their hashtag versions) were collected: “weed,” “marijuana,” “blunt,” “stoner,” “stoned,” “bong,” “pot,” “joint,” “kush,” “cannabis,” “pothead,” “ganja,” “indica,” “sativa,” and “#mmot” (meaning “Marijuana Movement on Twitter”). To compile this list, members from our research team initially composed a list of search terms that reflected the most commonly used terms for marijuana. We continued to build the list using terms related to marijuana on urbandictionary.com, a free online resource that tracks modern slang. We also added popular “related terms” as indicated by Google Trends, a key word research tool that provides near real-time search query trend data based on Google searches. For the terms “pot” and “joint,” we only included tweets that also had other words that would indicate the tweet was about marijuana (e.g., “smoke,” “legalize,” “roll”). We excluded tweets that included common terms that would render the tweet irrelevant for our purposes (e.g., Emily Blunt).

Among these marijuana-related tweets, those also containing at least one of the following alcohol-related terms (or their hashtag versions) were then identified: “drunk, “alcohol,” “beer,” “liquor,” “vodka,” and “hangover.” To identify these alcohol-related search terms, we compiled an inclusive list of drinking-related terms with input from our research team, Web searches, and searches of urbandictionary.com. From an initial list of more than 50 drinking-related key words, we used only those with an estimated ≥500,000 tweets per month—alone, not in combination with marijuana-related terms—and that did not produce large amounts of irrelevant tweets, as determined by searching the terms on Topsy. com, a real-time search engine that estimates tweet volume for specific key words over selected periods of time and shows recent tweets with those key words. We excluded terms that would indicate the tweet was not about alcohol (e.g., drunk in love, rubbing alcohol).

Analysis Strategies

To examine the themes of the most influential tweets that contained both marijuana- and alcohol-related terms, we used proc surveyselect in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) to randomly sample 5000 tweets (that were not direct @replies) from those whose handles were in the top 25th percentile for both number of followers and Klout score. Klout score is a measure of influence that considers the extent to which the user’s content is “acted upon” by being clicked, replied, and/or retweeted.20We chose to sample from tweets in the top 25th percentile of these measures in order to focus on tweets that would have more influence and reach. A total of 5000 tweets randomly sampled from the 23,876 tweets that were in the top 25th percentile of both Klout score and number of followers would allow estimation of the sentiment of tweets (e.g., normalizes both substances) with 95% confidence level with a margin of error of at least ±1.2%). Tweets that were direct @replies were excluded from qualitative analysis because the conversation often would also need to be reviewed in order to understand the context.

Each tweet (along with the content of any links) was qualitatively analyzed to determine sentiment about the substances, including whether the content normalized use of the substances (without preferring one substance over the other), reflected a preference of marijuana over alcohol, reflected a preference of alcohol over marijuana, or was against or discouraged both substances. If it was difficult to discern the tweet or it appeared neutral in sentiment to both alcohol and marijuana, the tweet was coded as “neutral/can’t tell.”

Subthemes for each sentiment were also coded to better understand the various sentiments about the substances. Two members of the research team with expertise in substance use disorder research scanned 500 random tweets in order to classify common subthemes of interest, such as reasons for preferring one substance over the other (e.g., liking the effects of marijuana better than alcohol, marijuana is safer than alcohol); mentioning sex or romance, tobacco or other drugs, famous people, music, or the entertainment industry; and using substances with friends. These subthemes were used to code the full set of sampled tweets, and multiple subthemes could be present in a tweet. The presence of subthemes of interest was coded as yes/no.

The source of the tweet was coded as a marijuana- or alcohol-focused handle (e.g., had a reference to alcohol or marijuana in the name), health or government organization/health professional, or other type of handle that does not fall into the above categories.

We used the crowdsourcing services of CrowdFlower to code the tweets (http://www.crowdflower.com). Crowdsourcing involves using a large network of online (i.e., virtual) workers to complete microtasks. Similar crowdsourcing methodologies have previously been used, with high levels of agreement between trained research coders and crowdsourced coders.21 The sample of tweets and coding instructions were uploaded onto the online platform for CrowdFlower contributors (i.e., persons who work on the coding tasks) to code. A set of 200 tweets (from the total 5000 tweets) coded by two trained members of the research team were used as test tweets. Before CrowdFlower contributors could begin coding they were required to correctly code at least 7 of 10 test tweets. Additional test tweets were hidden from contributors and also were interspersed throughout the full sample of tweets to ensure that the CrowdFlower contributors responded to tasks to a high standard. If a contributor’s accuracy on test items (i.e., trust score) fell below 70%, he or she was dropped from the project; all prior codes from those coders were discarded and new coders were assigned in their place.

Each tweet was coded by at least three CrowdFlower contributors. The response with the highest confidence score was chosen. Confidence score describes the level of agreement between multiple contributors, is weighted by the contributors’ trust scores, and indicates “confidence” in the validity of the result (https://success.crowdflower.com/hc/en-us/articles/201855939-Get-Results-How-to-Calculate-a-Confidence-Score). We coded a random sample of 200 tweets that were nontest items and compared our responses with final CrowdFlower responses. We report percent agreement, which indicates the simplest calculation of agreement in responses between the research team and final CrowdFlower responses. Because percent agreement does not take into account agreement due solely to chance, we also report Cohen kappa, a measure of interrater agreement that does account for agreement that occurs by chance.22 Agreement was moderate for sentiment, which had multiple categories of response (percent agreement, 77%; kappa, .60; 95% confidence interval, .50–.69), and there was no indication of systematic differences in sentiment coding between the research team and Crowd-Flower responses (Bhapkar test for marginal homogeneity p = .175; Bhapkar test evaluates the difference of the marginal distribution for categoric variables, and a nonsignificant finding indicates no difference in marginal distributions).23 Agreement was good for the source of the tweets (percent agreement, 96%; kappa, .83) and presence of subthemes (median percent agreement, 94%; interquartile range, 91%–97%; median kappa, .76; interquartile range, .61–.87).

RESULTS

Marijuana- and Alcohol-Related Tweet Volume and Popular Retweets

A total of 195,277 tweets with both the marijuana- and alcohol-related terms of interest were collected from February 4 to March 5, 2014. This represented approximately 3% of the more than 7.5 million marijuana-related tweets collected during that month. The median number of followers of the marijuana and alcohol tweets was 332 (interquartile range, 153–709), and the median Klout score was 39.2 (interquartile range, 32.1–43.6). Examples of some of the most popular retweets include: “Stoner chicks over drunk chicks any day” (tweeted on February 12; more than 1500 retweets), and “You smoke pot? Sorry, we can’t hire you. You get shitfaced every weekend at the club after 6 beers and 12 shots? You’re hired!” (tweeted on February 22; nearly 1000 retweets).

Sentiment, Subthemes, and Source of Tweets

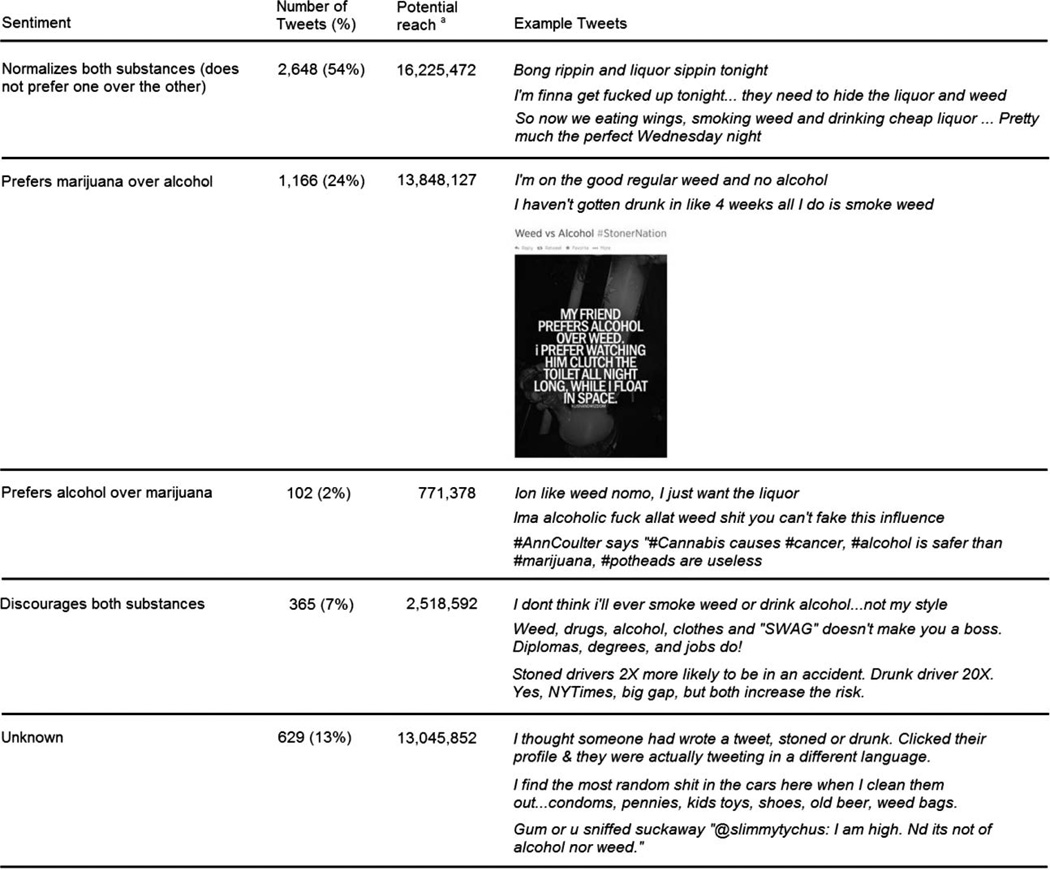

We randomly sampled from tweets that were not direct @replies and were in the top 25th percentile of both followers and Klout score (≥709 followers and ≥44 for Klout score, n = 23,876). Among the randomly sampled 5000 tweets, 4910 (98%) were about alcohol and marijuana. Only 90 tweets (2%) were not discernibly about marijuana and alcohol and were excluded from further analysis. Sentiment, potential reach of the tweets, and example tweets are shown in Figure 2. Among the 4910 marijuana- and alcohol-related tweets, 2648 (54%) normalized marijuana and/or alcohol (without preferring one substance over the other), 1166 (24%) preferred marijuana over alcohol, 102 (2%) preferred alcohol over marijuana, and 365 (7%) were against/discouraged both substances. The sentiment could not be determined or was neutral for approximately 13% (n = 629) of the tweets. The potential reach, or total of all of the followers of the tweets, was greatest for tweets normalizing the substances (without a preference for one over the other), with more than 16 million total followers (16,225,472), followed by tweets that preferred marijuana over alcohol (13,848,127 total followers). The potential reach does not take into account the extended audience (i.e., followers’ followers and their followers), which would render the potential reach ever larger than currently estimated.

Figure 2.

Sentiment and Reach of Tweets That Mention Both Marijuana and Alcohol (N = 4910)

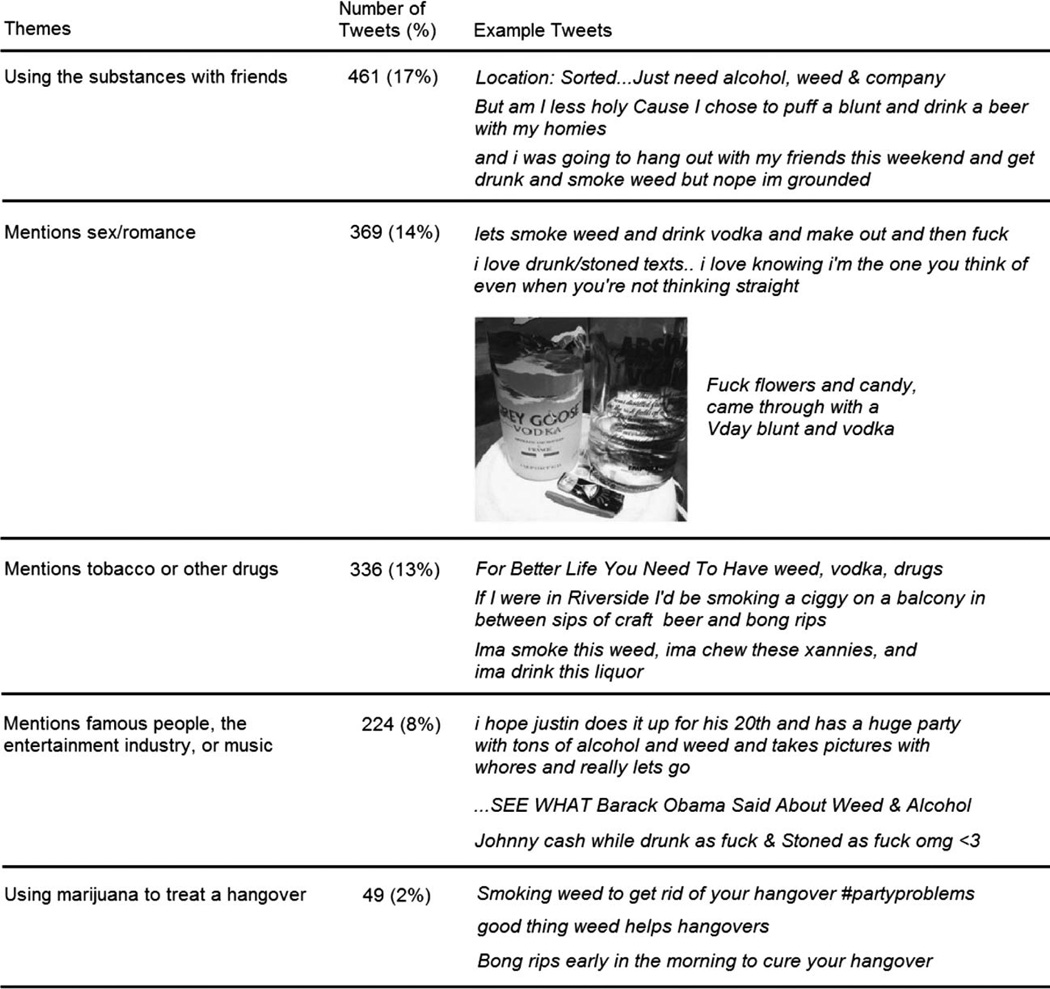

Subthemes among the tweets that normalized marijuana and/or alcohol (with no preference of one substance over the other, n = 2648) are shown in Figure 3. Approximately 17% (n=461) mentioned using marijuana and/or alcohol with friends, followed by 14% (n = 369) mentioning sex/romance, and 13% (n = 336) mentioning tobacco or other drugs.

Figure 3.

Subthemes of Tweets That Normalized Marijuana and Alcohol Use (N = 2648)

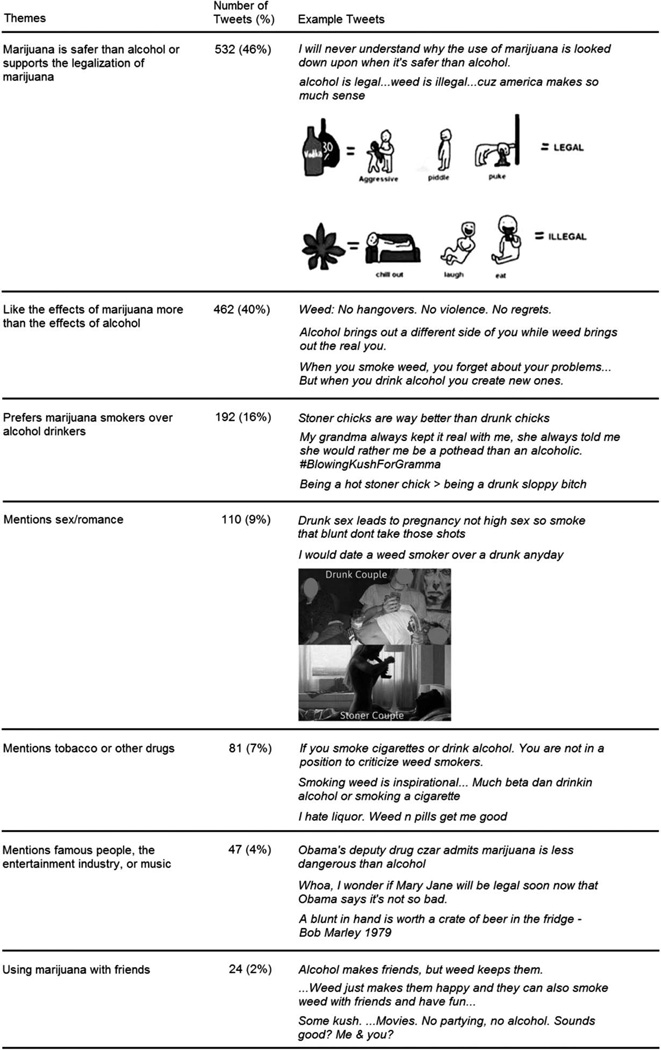

Among the tweets that preferred marijuana over alcohol (n = 1166; Figure 4), the most common subtheme was that marijuana is safer than alcohol or that marijuana should be legal if alcohol is legal (n = 532; 46%). Another common subtheme was partiality for the effects of marijuana compared with those of alcohol (n = 462; 40%).

Figure 4.

Subthemes of Tweets That Expressed a Preference for Marijuana Over Alcohol (N = 1166)

Of the few tweets that preferred alcohol over marijuana (n =102), 47% (n = 48) explicitly expressed liking the effects of alcohol more than marijuana. Among the tweets that discouraged use of both substances (n = 365), 39% (n = 141) expressed not liking people who used the substances, and 38% (n= 139) focused on the adverse health effects or other negative consequences of using the substances.

Overall, 9% (n=460) of tweets came from a marijuana- and/or alcohol-focused handle, identified by whether an alcohol- or marijuana-related term is in the handle name. Less than 1% (n = 17) of tweets came from someone with a handle associated with a health or government organization/health professional. The large majority of tweets (90%; n = 4433) came from some other type of handle that does not fall into the above categories.

CONCLUSION

Our content analysis of influential tweets about both marijuana and alcohol found that more than half of the tweets in our sample (54%) normalized the use of both of substances. These tweets also had the greatest potential reach, or sum of all followers. Although the volume of tweets that mention both marijuana and alcohol (about 200,000 tweets per month) is far less than tweets that mention marijuana (more than 7.5 million tweets per month) or alcohol (12 million tweets per month),24,25 our findings do corroborate such studies that have found peer-to-peer promotion of substance use behaviors on social media.11–16 Social media messages that normalize polysubstance use encourage risk behaviors that are already common among young people and are associated with increased likelihood of substance use disorders, negative social outcomes, depression, and unsafe driving.26–31

Nearly a quarter of the tweets in our sample reflected a preference for marijuana use over drinking alcohol. Common subthemes of these tweets included the idea that marijuana-related highs have no hangover effects (vs. getting drunk). Tweeters mentioned that “stoners” feel relaxed and happy after smoking marijuana vs. “drunks,” who often exhibit violent or aggressive behavior. Furthermore, tweeters believed that recreational marijuana use is safer than binge drinking. These social media messages may shed light on why national surveys are observing a liberalizing of marijuana use attitudes, especially among young people. The belief that marijuana is safer than alcohol appears to be a popular opinion on Twitter. In fact, some expert opinions do suggest that marijuana may be less harmful than alcohol,32 and tweets referring to President Obama’s 2014 quote, “I don’t think it (weed) is more dangerous than alcohol” were relatively popular. The scientific community has recognized that more population-based research on outcomes of marijuana involvement is a public health priority. In the meantime, the spread of tweets that normalize marijuana use could further encourage increases in marijuana use and perhaps a substitution of marijuana for alcohol. Thus, it is important for online and offline prevention programs to discuss the known short-term and long-term risks that are associated with marijuana use, especially among adolescents, so that they are not ignored.33

A fair amount of tweets encouraged other health-risk behaviors in conjunction with substance use. For example, individuals posted tweets about “getting high and/or drunk” to enhance and facilitate romantic relationships. Because substance use risk behaviors have been associated with deleterious sexual health consequences,34–39 it is concerning that we found numerous tweets that normalize substance abuse in the context of sexual and romantic situations. Prevention efforts that highlight the potential consequences of mixing substance use with sexual behaviors are needed to offset the potential influences of these troubling tweets.

Our study also highlights the ability to use social media data to improve our understanding of young people’s beliefs and risk perceptions about substance use, because most of the people who tweet about substance use are young.24 Mining social media data has the potential to provide a quicker and richer understanding of young people’s attitudes than the use of self-reported questionnaires. This can allow researchers and public health advocates to develop new prevention programs (both offline and online) that can provide normative education and confront such prosubstance beliefs. On social media, public health organizations could purchase targeted ads and work to more effectively spread prevention messages to increase awareness of risks associated with polysubstance use and marijuana use.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting results from our study. We only examined messages on Twitter; thus, results cannot necessarily be generalized to other social media platforms. The tweets we examined included a specific list of marijuana- and alcohol-related terms that is not comprehensive and thus does not represent the full volume of marijuana- and alcohol-related tweets in the Twitter stream. We cannot verify that the messages contained in the tweets about substance use actually reflect real substance use behavior. Finally, we randomly sampled from those tweets with handles that had a high Klout score and number of followers, which may disproportionately sample extremely popular accounts and celebrities. However, in a sensitivity analysis we excluded those tweets with more than 20,000 followers and a Klout score of ≥60, and results were similar to those reported.

Our study findings highlight the substance use messages on Twitter that normalize marijuana and alcohol use behaviors. Many tweets revealed a preference for marijuana use over binge drinking that is being fueled, at least in part, by opinions that marijuana use is safe and produces more relaxing and beneficial effects vs. alcohol use. Tweets also encouraged other risky health behaviors, including sex or romantic relationships in the context of substance use. Young people are highly influenced by their peers and are at a critical stage of development when substance use behaviors and attitudes are being shaped.40–42 Without an effective counterbalance that dissuades substance use, the preponderance of influential tweets that normalize substance use could certainly have a negative impact on the youth and young adults who are exposed to these messages. Our findings highlight the need for prevention efforts, both offline and online, to deliver messages about the risks associated with marijuana and alcohol abuse.

SO WHAT? Implications for Health Promotion Practitioners and Researchers.

What is already known on this topic?

Young people often post about experiences with substance use on social media. Given recent changes in risk perceptions about marijuana and alcohol, we examined posts about both substances on Twitter to glean insight into the sentiment about these substances when mentioned together.

What does this article add?

More than half of the tweets analyzed normalized the use of both substances, and nearly one-quarter expressed a preference for marijuana over alcohol. Among the latter, it was commonly thought that marijuana is safer or that marijuana’s effects were better than those of alcohol.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Tweets that normalize substance use could negatively affect those exposed to such messages. There is a need for online and offline prevention efforts to deliver messages about the risks associated with marijuana and alcohol abuse, with additional focus on polysubstance use.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grants R01 DA039455 and R01 DA032843, awarded to P.A.C.-R.; a National Institutes of Health Midcareer Investigator Award, awarded to L.J.B. (K02 DA021237); and grant R01 DA031288, awarded to R.A.G.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, Md: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. NSDUH Series H-48; HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachman JG, Johnson LD, O’Malley PM. Explaining recent increases in students’ marijuana use: impacts of perceived risks and disapproval, 1976 through 1996. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:887–892. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer P, Greitemeyer T, Kastenmuller A, et al. The effects of risk-glorifying media exposure on risk-positive cognitions, emotions, and behaviors: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:367–390. doi: 10.1037/a0022267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, et al. The social norms of birth cohorts and adolescent marijuana use in the United States, 1976–2007. Addiction. 2011;106:1790–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Primack BA, Kraemer KL, Fine MJ, Dalton MA. Media exposure and marijuana and alcohol use among adolescents. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:722–739. doi: 10.1080/10826080802490097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slater MD, Henry KL. Prospective influence of music-related media exposure on adolescent substance-use initiation: a peer group mediation model. J Health Commun. 2013;18:291–305. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.727959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker JS, Miles JN, D’Amico EJ. Cross-lagged associations between substance use-related media exposure and alcohol use during middle school. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:460–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, et al. Birth cohort effects on adolescent alcohol use: the influence of social norms from 1976 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1304–1313. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking prevalence and predictors among national samples of American eighth- and tenth-grade students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:41–45. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol references on undergraduate males’ Facebook profiles. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5:413–420. doi: 10.1177/1557988310394341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glassman T. Implications for college students posting pictures of themselves drinking alcohol on Facebook. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2012;56:38–58. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno MA, Christakis DA, Egan KG, et al. Associations between displayed alcohol references on Facebook and problem drinking among college students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:157–163. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan EM, Snelson C, Elison-Bowers P. Image and video disclosure of substance use on social media websites. Comput Human Behav. 2010;26:1405–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavazos-Rehg P, Krauss M, Grucza R, Bierut L. Characterizing the followers and tweets of a marijuana-focused Twitter handle. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e157. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Litt DM, Stock ML. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: the roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:708–713. doi: 10.1037/a0024226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang GC, Unger JB, Soto D, et al. Peer influences: the impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner J. Pew internet: social networking. [Accessed October 17, 2014]; Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/social-networking-fact-sheet/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Cristofaro E, Soriente C, Tsudik G, Williams A. Hummingbird: privacy at the time of Twitter. Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP’12); IEEE Computer Society; 2012. pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quercia D, Ellis J, Capra L, Crowcroft J. In the mood for being influential on twitter. Paper presented at: Privacy, Security, Risk And Trust (PASSAT) and 2011 IEEE Third Inernational Conference on Social Computing (SocialCom); IEEE Computer Society; 2011. pp. 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim A, Murphy J, Richards A, et al. Can tweets replace polls?: a US health-care reform case study. In: Hill CA, Dean E, Murphy J, editors. Social Media, Sociality, and Survey Research. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen JA. Coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhapkar VP. A note on the equivalence of two test criteria for hypotheses in categorical data. J Am Stat Assoc. 1966;61:228–235. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss M, Fisher SL, Salyer P, Grucza RA, Bierut LJ. Twitter chatter about marijuana. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavazos-Regh PA, Krauss MJ, Sowles SJ, Bierut LJ. “Hey everyone, I’m drunk.” An evaluation of drinking-related Twitter chatter. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:635–643. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Briere FN, Fallu JS, Descheneaux A, Janosz M. Predictors and consequences of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2011;36:785–788. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Midanik LT, Tam TW, Weisner C. Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramaekers JG, Robbe HW, O’Hanlon JF. Marijuana, alcohol and actual driving performance. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2000;15:551–558. doi: 10.1002/1099-1077(200010)15:7<551::AID-HUP236>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swartzwelder NA, Risher ML, Abdelwahab SH, et al. Effects of ethanol, Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol, or their combination on object recognition memory and object preference in adolescent and adult male rats. Neurosci Lett. 2012;527:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among US high school seniors from 1976 to 2011: trends, reasons, and situations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Alcohol and marijuana use patterns associated with unsafe driving among US high school seniors: high use frequency, concurrent use, and simultaneous use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:378–389. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007;369:1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volkow ND, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:879. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1407928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard DE, Wang MQ. The relationship between substance use and STD/HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among US adolescents. J HIV/AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2006;6:65–82. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kingree JB, Braithwaite R, Woodring T. Unprotected sex as a function of alcohol and marijuana use among adolescent detainees. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNaughton Reyes HL, Foshee VA, Bauer DJ, Ennett ST. Proximal and time-varying effects of cigarette, alcohol, marijuana and other hard drug use on adolescent dating aggression. J Adolesc. 2014;37:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, et al. Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: the influence of psychosocial factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simons JS, Maisto SA, Wray TB. Sexual risk taking among young adult dual alcohol and marijuana users. Addict Behav. 2010;35:533–536. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Gelder MM, Reefhuis J, Herron AM, et al. Reproductive health characteristics of marijuana and cocaine users: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43:164–172. doi: 10.1363/4316411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sher KJ, Grekin ER, Williams NA. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict Behav. 2012;37:747–775. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]