Abstract

The present study evaluated cultural, ethnic, and gender differences in drinking and alcohol-related problems among Hispanic students. Familism protects against negative outcomes in Hispanic populations, thus we expected familism to buffer against alcohol problems. Participants (N =623; 53% female) completed a battery of measures. Results suggested that familism was protective against drinking. Furthermore, alcohol use mediated the association between familism and alcohol-related problems. In sum, understanding that culture plays an important role in people’s behaviors and identifying protective factors is critical to inform culturally sensitive prevention and intervention efforts.

Keywords: Alcohol abuse, alcohol use, culture, drinking, Hispanics

Hispanics by definition have a Spanish-speaking background and originate from countries such as Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba (Pew Hispanic Center, 2014). Estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau (2014) indicate that around 54 million individuals of Hispanic descent currently reside in the United States. As such, Hispanic individuals are the largest ethnic or racial minority in the United States, accounting for 17% of the total population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Hispanics are also the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States (Pew Hispanic Center, 2014). The Hispanic population is projected to reach 128.8 million people by the year 2060, which would equate to 31% of the total population of the United States. Despite the ever-increasing number of Hispanic individuals living in the United States, only 6.8% of undergraduate and graduate students attending college identify as Hispanic (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). However, the number of Hispanic college students is increasing and will likely continue to increase (Frey & Lopez, 2012). Thus further research exploring behaviors and processes specific to Hispanic college students is warranted.

College drinking

One such domain in which research on Hispanic college students has been somewhat limited is alcohol use. The alcohol literature repeatedly demonstrates that alcohol consumption among college students is both prevalent and a public health concern. Specifically, the 2012 Monitoring the Future data revealed that 4 out of 5 students have consumed alcohol, 61.0% have been drunk in the past year, 40.1% have been drunk in the past month, and 3.9% drink daily (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013). Moreover, compared to females, males have higher rates of binge drinking and alcohol-related problems (Johnston et al., 2013). In addition, with respect to racial and ethnic rates of drinking, research suggests that 46.6% of Whites, 32.3% of Hispanics, 20.3% of Asians, and 14.4% of African Americans engage in heavy drinking (Paschall, Bersamin, & Flewelling, 2005). Furthermore, when compared to their non-college-attending peers, college students report higher rates of heavy-episodic drinking (Johnston et al., 2013). This pattern of heavy alcohol consumption among college students can have serious consequences for the heavy drinking individual as well as for his or her friends and family (e.g., academic neglect, psychological or interpersonal problems, unsafe driving, vandalism, risky sexual behavior/victimization, physical injuries/harm; Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005; Nelson, Xuan, Lee, Weitzman, & Wechsler, 2009). While heavy drinking and experiences of negative alcohol-related consequences are relatively common among college students, past research has found racial and ethnic differences in alcohol use patterns (e.g., Caetano, Baruah, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Ebama, 2010; Dawson, 1998), suggesting the importance of considering such differences. As Hispanics are a growing ethnic group in the United States, the present study examined differences in alcohol use and related problems between Caucasian and Hispanic college students.

Hispanic drinking

Overall, Hispanic youth tend to initiate drinking at an earlier age when compared to their White counterparts and are more likely than their peers to abuse alcohol (Eaton et al., 2012; Johnston et al., 2013; Siqueira & Crandall, 2008). Furthermore, heavy episodic drinking has been shown to be common among Hispanic adolescents, with nearly half (47.5%) of respondents in one study reporting at least one heavy drinking episode per week (Venegas, Cooper, Naylor, Hanson, & Blow, 2012). Interestingly, research suggests that Hispanic individuals are less likely to become dependent on alcohol (9.5%) when compared to non-Hispanic Whites (13.8%). However, it is important to note that 33% of Hispanics who develop a dependence on alcohol will have recurrent and persistent problems, which is significantly higher than their non-Hispanic White counterparts (22.8%; Chartier & Caetano, 2010).

Recent research examining Hispanic alcohol use has examined factors related to Hispanic culture, such as changes in one’s attitudes and acculturation (e.g., Caetano & Clark, 2003; Raffaelli et al., 2007) that may influence ethnic differences in drinking patterns. For example, research suggests the young U.S. born Hispanic men who are not Protestant have more relaxed attitudes toward alcohol use and that those indiviudals are more likely to drink, drink more heavily, and possibly have more alcohol-related problems (Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, & Rodriguez, 2010). Furthermore, when considering acculturation, as Hispanic families adapt their beliefs, values, and behaviors to align with American culture they experience changes that include an increase in alcohol consumption. Based on work done by Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, and Szapocznik (2010) aimed at refining how acculturation is defined (e.g., expanded to include cultural practices, cultural values, and cultural identifications), it follows that one element of a Hispanic’s cultural values that may play an important role in considering alcohol use patterns is familism.

Familism

Familism has been defined as an emphasis on having positive family relationships and generally being dedicated, respectful, and loyal to one’s family (Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Marín, & Perez-Stable, 1987; Steidel & Contreras, 2003). Familism is an important concept within the Hispanic community (Harwood, Leyendecker, Carlson, Asencio, & Miller, 2002; Miranda, Estrada, & Firpo-Jimenez, 2000; Zinn, 1982). Research demonstrates that Hispanic individuals report higher levels of familism than Anglo-Americans (Ramirez et al., 2004). Hispanic families tend to be collectivistic, providing financial and emotional support to and placing priority on the family unit (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999).

Researchers suggest that familism and family cohesion are analogous to each other, such that both terms are used to describe close relationships between family members, including those of other and, most often, older generations (Behnke et al., 2008). In addition, researchers agree that the construct of familism is multifaceted. Specifically, Valenzuela and Dornbusch (1994) identified three main components of familism: the frequency with which individuals are in contact with their families (behavior), the number of family members that live in close proximity to one another (structure), and the extent to which younger family members participate in taking care of older family members (attitudes). More recently, Steidel and Contreras (2003) found support for four components of familism: familial support, familial interconnectedness, familial honor, and subjugation of self for family.

Familism tends to be associated with positive outcomes for Hispanic individuals, including reduced parental stress and increased academic support for Mexican American adolescents (Roosa, Dumka, & Tien, 1996). Furthermore, Hispanic students who reported being higher in familism were found to report expending more effort in academic settings and were less truant (Esparza & Sanchez, 2008). Latino individuals higher in familism were found to be less likely to engage in aggressive behavior, have conduct problems (e.g., swearing or using foul language) and report breaking rules (e.g., skipping school) (Marsiglia, Parsai, & Kulis, 2009). Moreover, familism and related constructs such as time spent with family members and family cohesion have been associated with lower levels of smoking behavior (Coonrod, Balcazar, Brady, Garcia, & Van Tine, 1999), alcohol use (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000), delinquency (Pabon, 1998), and child maltreatment (Coohey, 2001) among Hispanic individuals. Thus, the present study hypothesized that, overall, familism would buffer against problem alcohol use for Hispanic individuals.

Gender differences in drinking and familism

Prior research has demonstrated both that familism tends to be protective against heavy alcohol use (e.g., Gil et al., 2000; Strunin et al., 2013) and that women tend to drink less than men overall (e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2007). More specifically, past investigations have repeatedly found that Hispanic women drink less and are less likely to engage in binge drinking compared to their Hispanic male counterparts (Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, & Rodriguez, 2010). In addition, research on a national sample found that ethnic differences were less apparent in women compared to men (Nielsen, 2000). However other studies specifically examining associations between alcohol use and acculturation have found gender differences such that acculturation was more strongly associated with drinking for Hispanic women (Caetano & Clark, 2003; Raffaelli et al., 2007) and less strongly associated with drinking for Hispanic men (Alaniz, Treno, & Saltz, 1999; Marín & Posner, 1995; Raffaelli et al., 2007). Taken together, these studies suggest that cultural influences on alcohol use may differ by gender and more research is needed to understand these differences.

Gender differences in drinking behaviors between Hispanic men and women may be related to family characteristics. For example, females in Hispanic cultures are often socialized to be feminine and to take care of chores inside the home, whereas males are encouraged to help with chores outside the home and demonstrate machismo (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). Girls are often more limited in their freedoms, whereas boys are not as restricted and are able to participate in activities outside of the home (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). Along with gender role socialization, familism is a cultural construct that is passed down at an early age. According to Parveen and Morrison (2009), familism is influenced by gender differences such that women are more likely than men to take on the traditional role of being a caregiver. In Hispanic culture, it is more acceptable for Hispanic men to drink compared to women because drinking is a part of the culture and it represents that men have earned respect within their family and/or social circles, are accomplished, and economically stable.

Current study

Given previous research suggesting that familism is a protective factor among Hispanics against maladaptive behaviors, the current study aimed to evaluate familism in the context of problem alcohol use. Specifically, familism is a core value of Hispanic culture that has been shown to protect against heavy drinking (Gil et al., 2000; Strunin et al., 2013), and previous literature has shown gender differences in drinking among Hispanics (Ramisetty-Mikler et al., 2010), thus we hypothesized that familism would be associated with lower rates of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems and that this association would differ for males compared to females. Specifically, we expected familism to be more strongly protective among Hispanic women compared to Hispanic men.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants included 623 undergraduates (53% female) from 3 regionally diverse U.S. universities who were between the ages of 18 and 26 and met heavy drinking criteria, which was defined as individuals who reported drinking 4 to 5 drinks on one occasion for women and men respectively in the past month. Students had a mean age of 20.55 years (SD =1.70). Participants reported the following racial backgrounds: 62% White/Caucasian, 1% Native American, 16% Asian, 5% Black/African American, 1% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 8% Mixed, and 7% other. With regard to ethnicity, 21% of the sample was Hispanic. For the purposes of the current study, only non-Hispanic Whites and White Hispanics were retained in the sample (N =604).

A list of all registered students for the fall 2012 semester was obtained from each respective university. Each campus invited a random sample of registered students via e-mail to participate in an online screening survey. In order to be eligible for the longitudinal trial, participants had to be between 18 and 26 years old and meet the criteria for heavy drinking. These students were invited to participate in the longitudinal trial aimed at reducing alcohol use among college students and were compensated $25 for completing the survey. The data for the current study come from wave one of the longitudinal trial.

Measures

Demographics

Participants provided demographic information such as age, gender, racial and ethnic background, relationship status, and student status.

Attitudinal familism scale

Familism, or attitudes toward one’s family, was assessed using a modified version of the Attitudinal Familism Scale (AFS; Steidel & Contreras, 2003). This 18-item questionnaire asked participants questions such as, “A person should always be expected to defend his or her family’s honor no matter what the cost” and “A person should be a good person for the sake of his or her family.” Participants responded to questions using a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree; α =.88).

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was assessed with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Participants were asked, “Consider a typical week during the past three months. How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), do you drink on each day of a typical week?” Participants provided estimates for the typical number of drinks they consumed on each day of the week. Responses were summed to reflect the average number of drinks consumed per week over the past three months.

Alcohol-related problems

A modified version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) assessed how often participants experienced 25 alcohol-related problems over the previous 3 months. The RAPI was modified to include 2 additional items (e.g., “Drove after having 2 drinks” and “Drove after having 4 drinks”). Participants responded to the statements using a 5-point scale (0 =never; 1 =1–2 times; 2 =3–5 times; 3 =6–10 times; 4 =more than 10 times). Scores were calculated by summing the 25 items (α =.91).

Plan of analyses

The primary model of interest in the current study is moderated mediation. First, we hypothesized that Hispanic individuals high in familism would have lower rates of alcohol use. Moreover, we were interested in whether this might vary by gender. Finally, we were interested in examining how this might relate to alcohol-related problems. Thus, we began by examining a three-way interaction among familism, ethnicity, and gender predicting alcohol use. Next, we examined a model wherein familism, ethnicity, and gender interacted to predict alcohol use, with alcohol use mediating the association between familism, ethnicity, gender, and alcohol-related problems. We used the PROCESS macro for SAS, model 11 (Hayes, 2013). PROCESS is a statistical procedure that can be used for testing conditional process models. Specifically, these models are used when the primary aim is to understand and describe the conditional nature of the process by which a variable has an influence on another (in the current work, moderated mediation). With conditional indirect effects, hypotheses are tested through the construction of standard errors and bootstrapped confidence intervals. Mediation is evaluated by computing the indirect path following the ab product term approach (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002) as well as bootstrapped 95% asymmetric confidence intervals around the indirect effect (Hayes, 2013; MacKinnon et al., 2002).

Results

Descriptives

Overall, White Non-Hispanic participants reported drinking an average of 11.37 (SD =.65) drinks per week while White Hispanic participants reported drinking an average of 10.31 (SD =6.90) drinks per week. Furthermore, White Non-Hispanic participants reported having an average of 5.20 (SD =5.77) alcohol related consequences while White Hispanic participants reported having an average of 5.80 (SD =6.81) alcohol related consequences. Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all variables are presented in Table 1. Zero-order correlations revealed significant, positive associations between gender and drinks per week such that men reported consuming more alcohol in a typical week than women. Moreover, results also suggested a positive association between ethnicity and familism suggesting that Hispanic individuals reported higher levels of familism than Caucasian individuals. The zero-order association between familism and drinking was not significant.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | — | ||||

| Ethnicity | −0.03 | — | |||

| Familism | 0.07 | 0.17*** | — | ||

| Drinks per Week | 0.29*** | −0.04 | −0.01 | — | |

| Alcohol-Related Problems | 0.16*** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.45*** | — |

| Mean | 0.42 | 0.22 | 6.00 | 10.04 | 5.30 |

| Standard Deviation | N/A | N/A | 1.18 | 8.83 | 6.02 |

Note. N =604.

p < .001.

Gender, ethnicity, and familism associations with alcohol use

We systematically evaluated models examining ethnic and cultural aspects as moderators of the gender and alcohol use association. To do this, we used hierarchical multiple regression. Results presented in Table 2 show a main effect of gender in predicting alcohol use as expected, such that men reported consuming more alcohol than women. Next, we examined all possible two-way interactions. Results revealed a significant interaction between ethnicity and familism such that Hispanic individuals, higher in familism, consumed less alcohol when compared to non-Hispanic individuals lower in familism. This was consistent with the central hypothesis of the research, indicating that familism was protective against heavy drinking for Hispanics but was not protective for non-Hispanics.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analyses predicting drinks per week from gender, ethnicity, and familism.

| Criterion | Predictor | b | t | β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinks per Week | Step 1 | Gender | 5.23 | 7.54 | .29 | <.001 |

| Ethnicity | −.82 | −.96 | −.04 | .34 | ||

| Familism | −.02 | −.07 | .00 | .94 | ||

| Step 2 | Gender*Ethnicity | −.51 | −.30 | −.02 | .77 | |

| Gender*Familism | −.76 | −1.26 | −.27 | .21 | ||

| Ethnicity*Familism | 1.57 | −2.24 | −.47 | .02 | ||

| Step 3 | Gender*Ethnicity*Familism | −3.47 | −2.44 | −.77 | .02 |

Note. N =604.

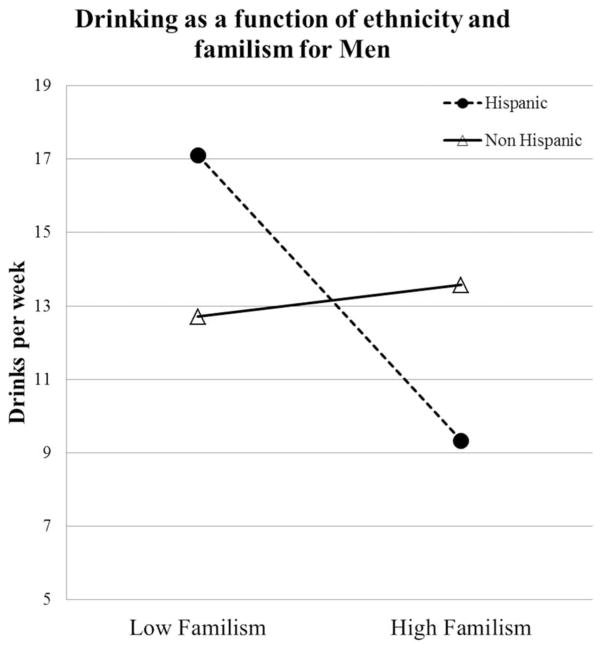

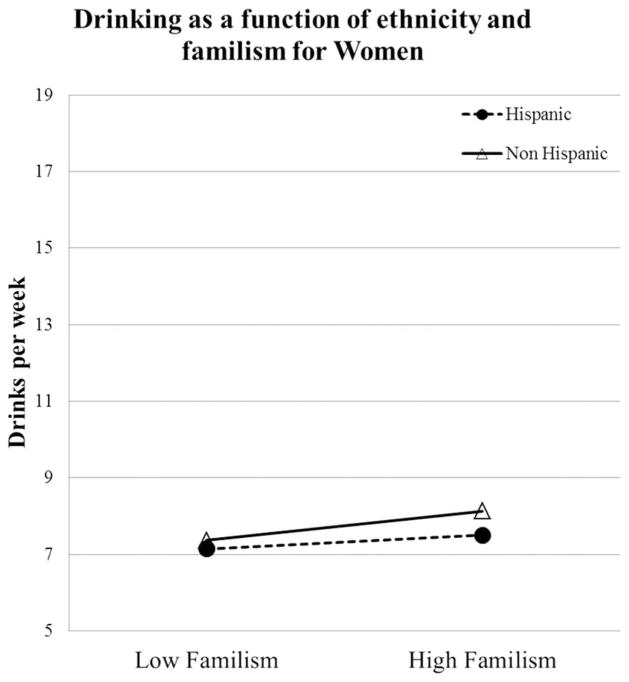

The three-way interaction between gender, ethnicity, and familism was also significant. Tests of simple slopes evaluated the association between familism and drinks per week for male and female Hispanics and non-Hispanics. Results are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. As shown in the figures, the ethnicity by familism interaction only emerged among men. Specifically, Hispanic men who are high in familism reported drinking less than non-Hispanic men and Hispanic men lower in familism. Thus, the results suggest that familism may be a protective factor against heavy alcohol use for specific groups—in this case, Hispanic men. This was contrary to what was expected, as we had anticipated the association would be stronger among Hispanic women than men.

Figure 1.

Drinking as function of ethnicity and familism for men.

Figure 2.

Drinking as function of ethnicity and familism for women.

Moderated mediation predicting alcohol-related problems

Next, we were interested in evaluating a model wherein alcohol use mediated the association between familism and alcohol-related problems. Furthermore, given the previous findings, we believed this mediation would be qualified by ethnicity and gender such that significant conditional indirect effects would emerge for Hispanic men high in familism. Using PROCESS model 11, we examined the conditional indirect effects of this moderated mediation. Results are presented in Table 3 and indicate that alcohol use did significantly mediate the association between familism and alcohol-related problems for Hispanic men, ab =1.01, SE =.48, [95% CI: −2.07, −.18] but not for Hispanic women, ab =.05, SE =.12, [95% CI: −.19, .30], non-Hispanic men, ab =.11, SE =.23, [95% CI: −.35, .55], and non-Hispanic women, ab =.10, SE =.08, [95% CI: −.05, .27]. Thus, for this sample, alcohol use mediated the familism–drinking problems link only for Hispanic men.

Table 3.

Indirect effects of familism on drinking problems through alcohol use for gender and ethnicity.

| Predictor | Moderator 1 (Ethnicity) | Moderator 2 (Gender) | Mediator | Outcome | Indirect Effect | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familism | Non-Hispanic | Female | Alcohol Use | Alcohol-Related Problems | 0.10 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.27 |

| Familism | Non-Hispanic | Male | Alcohol Use | Alcohol-Related Problems | 0.11 | 0.23 | −0.35 | 0.55 |

| Familism | Hispanic | Female | Alcohol Use | Alcohol-Related Problems | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.19 | 0.30 |

| Familism | Hispanic | Male | Alcohol Use | Alcohol-Related Problems | −1.01 | 0.48 | −2.07 | −0.18 |

Discussion

Prior research on alcohol use and ethnicity has shown that Hispanics tend to initiate drinking sooner and drink more heavily than Caucasians (Siqueira & Crandall, 2008). Thus, identifying potential factors that might buffer against heavy drinking and related problems is important for future research on ethnicity and substance use and in determining factors that may be helpful for developing future interventions. One such factor suggested by the present findings is familism. Results supported our primary hypothesis that familism was associated with less drinking among Hispanic students but was not protective against heavy drinking among non-Hispanic students.

We further anticipated that there would be gender differences in this effect such that this association would be particularly strong for Hispanic women relative to Hispanic men. Our results were the opposite of what we anticipated. That is, results indicated that familism was only associated with drinks per week among Hispanic men. In addition, drinks per week mediated the association between familism and alcohol-related problems, again only for Hispanic men. In retrospect, this finding suggests that familism may be particularly diagnostic for Hispanic men.

Cultural norms suggest that excessive alcohol use is less acceptable among Hispanic women than men (Caetano & Medina-Mora, 1988). Furthermore, “machismo” is a male gender role theme common among Latino populations. One aspect of machismo refers to hypermasculinity, which has been stereotypically associated with aggression, sexual promiscuity, and excessive alcohol consumption; whereas another aspect of machismo is associated with family honor (Kulis, Marsiglia, Lingard, Nieri, & Nagoshi, 2008). Kulis and colleagues (2008) found aggressive masculinity to be associated with higher risk of alcohol and other substance use and that gender identity tended to have stronger associations with risk behaviors for men than women. Given that men from Hispanic cultures tend to be high in both familism and machismo and that these factors have opposing influences on heavy drinking, additional work directly examining associations between these constructs would be worthwhile in further examining gender differences in Hispanic drinking.

The present study is among the first to examine alcohol use and related problems as a function of familism among Hispanic and non-Hispanic men and women. Results suggest that values and cultural expectations in Hispanic culture are important factors to consider when examining alcohol use and related problems. As expected, familism was associated with less alcohol use for Hispanic students but not for non-Hispanic students. In particular, results from the present study suggest that Hispanic men who place priority on their family (and the accompanying respect) are much less likely to report high levels of alcohol use. Perhaps this difference is partly accounted for by whom they spend their leisure time with. It is possible that students who are low in familism may be spending more time with other students and less time with their families.

Also of note is the high level of drinking among Hispanic men who are low in familism. As familism appears to be a positive factor, perhaps individuals who experience low familism, especially Hispanic men, might experience negative affect and be more likely to drink to cope (and thus report greater alcohol-related problems). These individuals may also be drinking for social reasons. Examining drinking motives in this population is a valuable avenue for future research.

Limitations and future directions

While this study makes an important step in understanding a specific acculturation factor, familism, and how it impacts alcohol use and related problems, the results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Namely, familism is only one component of acculturation, and future research should aim to examine familism while also controlling for other variables associated with acculturation, such as language use, nativity, and years spent in the receiving culture. Without controlling for these variables, it is difficult to tell whether the measure of familism is confounded by other aspects of acculturation. Furthermore, future research should examine the relationship between ethnic identity (another acculturation domain) and familism and isolate the predictive value of familism controlling for ethnic identity. It is important to note that the present findings were based on a sample from three universities and only included students who reported at least one heavy drinking episode in the previous month. Thus, it is difficult to know the extent to which findings may generalize. The overall pattern of findings is comparable to population based data among college aged U.S. residents (NSDUH; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014), with less drinking among women. National data suggest somewhat lower drinking among Hispanic individuals in this age group (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Although in the consistent direction, we did not find significant mean differences between Hispanics and non-Hispanics in this sample, which may have been due to the restricted range of drinking based on sampling. Finally, given the cross-sectional nature of the current study to causal inferences cannot be made. It would be interesting to examine the causal role that familism might play with respect to changes in drinking behavior throughout college and adulthood.

Conclusion

In sum, given prevalence rates of alcohol use in college students, and with the understanding that culture plays an important role in people’s behaviors, identifying protective factors for Hispanic young adults is critical to inform culturally-sensitive treatment and prevention efforts. The current research offers unique information regarding the important role familism plays among Hispanic males. Specifically, demonstrating that familism acts as a buffer against elevated alcohol use and related consequences for males offers two important pieces of information. It shows how culturally important variables protect against potentially negative behavior and also offers important areas for targeted prevention and intervention.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA014576 and manuscript preparation was supported in part by R00AA017669.

References

- Alaniz ML, Treno AJ, Saltz RF. Gender, acculturation, and alcohol consumption among Mexican Americans. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34:1407–1426. doi: 10.3109/10826089909029390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke AO, MacDermid SM, Coltrane SL, Parke RD, Duffy S, Widaman KF. Family cohesion in the lives of Mexican American and European American parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(4):1045–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00545.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Baruah J, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Ebama MS. Sociodemographic predictors of pattern and volume of alcohol consumption across Hispanics, Blacks, and Whites: 10-year trend (1992–2002) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(10):1782–1792. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Acculturation, alcohol consumption, smoking, and drug use among Hispanics. In: Chun KM, Balls Organista P, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Medina-Mora ME. Acculturation and drinking among people of Mexican descent in Mexico and the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1988;49:462–471. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(1–2):154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coohey C. The relationship between familism and child maltreatment in Latino and Anglo families. Child Maltreatment. 2001;6(2):130–142. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod DV, Balcazar H, Brady J, Garcia S, Van Tine M. Smoking, acculturation and family cohesion in Mexican-American women. Ethnicity & Disease. 1999;9(3):434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Beyond black, white and Hispanic: Race, ethnic origin and drinking patterns in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10(4):321–339. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, … Wechsler H. Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States, 2011 surveillance summaries. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012;61:1–162. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6104a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza P, Sanchez B. The role of attitudinal familism in academic outcomes: A study of urban, Latino high school seniors. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(3):193–200. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey R, Lopez MH. Hispanic student enrollments reach new highs in 2011. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; 2012. Aug, http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/08/20/hispanic-student-enrollments-reach-new-highs-in-2011/ [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70(4):1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):443–458. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(200007)28:4<443::aid-jcop6>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood R, Leyendecker B, Carlson V, Asencio M, Miller A. Parenting among Latino families in the US. Handbook of parenting. 2002;4:21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2012. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2013. p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad JM, Lopez MH. Hispanic Nativity Shift: U.S. births drive population growth as immigration stalls. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; 2014. Apr, http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/04/29/hispanic-nativity-shift/ [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Lingard EC, Nieri T, Nagoshi J. Gender identity and substance use among students in two high schools in Monterrey, Mexico. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Posner SF. The role of gender and acculturation on determining the consumption of alcoholic beverages among Mexican-Americans and Central Americans in the United States. International Journal of the Addictions. 1995;30:779–794. doi: 10.3109/10826089509067007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Parsai M, Kulis S. Effects of familism and family cohesion on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families in the southwest United States. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2009;18(3):203–220. doi: 10.1080/15313200903070965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda AO, Estrada D, Firpo-Jimenez M. Differences in family cohesion, adaptability, and environment among Latino families in dissimilar stages of acculturation. The Family Journal. 2000;8(4):341–350. doi: 10.1177/1066480700084003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Xuan Z, Lee H, Weitzman ER, Wechsler H. Persistence of heavy drinking and ensuing consequences at heavy drinking colleges. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(5):726–734. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen AL. Examining drinking patterns and problems among Hispanic groups: Results from a national survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2000;61(2):301–310. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabon E. Hispanic adolescent delinquency and the family: A discussion of sociocultural influences. Adolescence. 1998;33(132):941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen S, Morrison V. Predictors of familism in the caregiver role: A pilot study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(8):1135–1143. doi: 10.1177/1359105309343020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Bersamin M, Flewelling RL. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between college attendance and heavy alcohol use: A national study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(2):266–274. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles. 2004;50(5–6):287–299. doi: 10.1023/b:sers.0000018886.58945.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Torres Stone RA, Iturbide MI, McGinley M, Carlo G, Crockett LJ. Acculturation, gender, and alcohol use among Mexican American college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2187–2199. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JR, Crano WD, Quist R, Burgoon M, Alvaro EM, Grandpre J. Acculturation, familism, parental monitoring, and knowledge as predictors of marijuana and inhalant use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(1):3–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Rodriguez LA. The Hispanic Americans baseline alcohol survey (HABLAS): Alcohol consumption and sociodemographic predictors across Hispanic national groups. Journal of Substance Use. 2010;15(6):402–416. doi: 10.3109/14659891003706357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Dumka L, Tein J. Family characteristics as mediators of the influence of problem drinking and multiple risk status on child mental health. American Journal Of Community Psychology. 1996;24(5):607–624. doi: 10.1007/BF02509716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(4):397–412. doi: 10.1177/07399863870094003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65(4):237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira LM, Crandall LA. Risk and protective factors for binge drinking among Hispanic subgroups in Florida. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2008;7(1):81–92. doi: 10.1080/15332640802083238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidel AGL, Contreras JM. A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25(3):312–330. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strunin L, Díaz-Martínez A, Díaz-Martínez LR, Kuranz S, Hernández-Ávila CA, García-Bernabé CC, Fernández-Varela H. Alcohol use among Mexican youths: Is familismo protective for moderate drinking? Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;24(2):309–316. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9837-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH report: Gender differences in alcohol use and alcohol dependence or abuse: 2004 and 2005. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. [March 25, 2015];Facts for features: Hispanic heritage month 2014: Sept. 15–Oct. 15. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2014/cb14-ff22.html.

- Valenzuela A, Dornbusch SM. Familism and social capital in the academic achievement of Mexican origin and Anglo adolescents. Social Science Quarterly. 1994;75(1):18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Venegas J, Cooper TV, Naylor N, Hanson BS, Blow JA. Potential cultural predictors of heavy episodic drinking in Hispanic college students. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21(2):145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn MB. Familism among Chicanos: A theoretical review. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations. 1982;10:224–238. [Google Scholar]