Abstract

Thioesters and thioacetic acid (TAA) have been invoked as key reagents for the origin of life as activated forms of acetate analogous to acetyl-CoA. These species could have served as high-energy group-transfer reagents and allowed carbon insertions to form higher molecular weight compounds such as pyruvate. The apparent antiquity of the Wood-Ljungdahl CO2 fixation pathway and its presence in organisms which inhabit hydrothermal (HT) environments has also led to suggestions that there may be a connection between the abiotic chemistry of compounds similar to TAA and the origins of metabolism. These compounds’ apparent chemical simplicity has made their prebiotic availability assumed, however, although the kinetic behavior and thermochemical properties of TAA and analogous esters have been preliminarily explored in other contexts, the geochemical relevance of these compounds merits further evaluation. Therefore, the chemical behavior of the simplest thiolated acetic acid derivatives, TAA and methylthioacetate (MTA) were explored here. Using laboratory measurements, literature data, and thermochemical models, we examine the plausibility of the accumulation of these compounds in various geological settings. Due to the high free energy change of their hydrolysis and corresponding low equilibrium constants, it is unlikely that these species could have accumulated abiotically to any significant extant.

Several models for the origin of life invoke reactions occurring in the vicinity of volcanic or HT vent systems1,2,3. These are favored sites for the origin of life as they can be locations where considerable chemical disequilibrium is present, and high activation energy barriers to reaction, which are presently carried out by highly-evolved enzymes, may be overcome by the high temperatures present in such environments. High-energy compounds such as CO, COS, thioacids (R-COSH) and thioesters (R-COS-R′) are central to many of these schemes as feedstocks for primitive self-complexifying chemical cycles and the polymerization of biomolecules4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. These high-energy compounds are generally suggested to be derived from reactions with equilibria that are more favorable at higher temperatures13, though synthesis of some of the components of coenzyme A has been achieved at lower temperatures14. While the chemistry of CO and CO2 has received detailed attention in the context of equilibrium HT vent chemistry15,16, even the simplest thioacids and thioesters, such as thioacetic acid (TAA) and methyl thioacetic acid (MTA), have received considerably less. A notable exception is the work of Bracher et al.17 who compared the competition of transthioesterification and hydrolysis for thioesters. These authors concluded that near pH 7 and 25 °C, given sufficiently high initial concentrations of reactants, exchange between thioesters can compete with hydrolysis. This analysis, however, ignores questions of the sources of these compounds, and important aspects of the abiotic geochemistry of TAA, MTA and their homologs warrant detailed consideration.

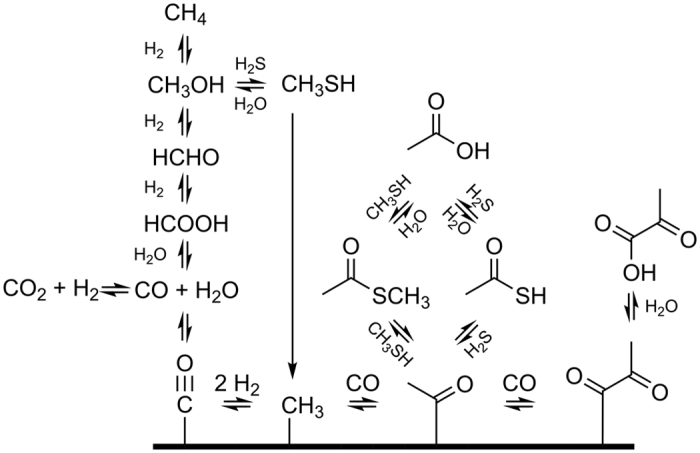

Several origin of life scenarios hypothesize that TAA, MTA or other thioacetate derivatives could have acted as acetyl-CoA analogues, donating acetate groups for organosynthesis in a primitive reverse tricarboxylic acid-(rTCA)-like cycle2,6,18,19 or as activating agents for carboxyl groups for transacylation reactions7,10,20. Conversion of geologic H2 and CO2 to CO through the water-gas shift reaction21, is often assumed to supply essential source materials for nascent biology. CO can be reduced to CH4 under geochemically plausible conditions, presumably via other intermediate oxidation-state C1 compounds such as HCHO and CH3OH15, the latter of which is also abundant in some geological settings, particularly in “serpentinizing systems,” in which reduced iron is oxidized by water yielding higher oxidation state iron oxides and H2 (Fig. 1)22.

Figure 1. Some proposed mechanisms for the abiotic production of TAA and MTA in HT settings.

The thick line represents a mineral surface (e.g., a metal sulfide or oxide).

CO has a high affinity for transition metals23, and surface catalysis is proposed to play a major role in several origin of life schemes involving thioesters, though sometimes the particular mineral is also a reagent in that it supplies reducing equivalents (e.g., chemistries involving the FeS-FeS2 redox couple24). Surface bound organics are then proposed to undergo carbonyl-insertion reactions, which have been experimentally verified to occur under laboratory conditions25, in a process which could ultimately give rise to autocatalytic chemical cycles which depend on thioesters2.

However, as TAA and thioesters are “high-energy” compounds, in that their hydrolysis is very thermodynamically favorable; their formation is then unfavorable, though the problems that may preclude their formation may be kinetic rather than thermodynamic, as we show here.

Interest in thioester chemistry due to the importance of CoA derivatives in biochemistry led to several controlled studies of their physical chemistry26,27,28. For example, TAA hydrolysis to acetic acid over a wide range of pH and temperature values has been explored to allow comparison with CoA hydrolysis. ΔG and Ea values for this reaction are available in the chemical literature26,28.

We examine here the equilibrium and kinetics of formation and hydrolysis of TAA and MTA using literature data corroborated and bolstered with experimental data over a wide geochemically relevant set of conditions. The abiotic chemistry of thioesters and their possible occurrence in natural HT environments is then discussed in the context of prebiotic chemistry.

Materials and Methods

Acetic acid (99.99%), sodium methanethiolate (95%), Na2S·9 H2O (98%), NaHS·x H2O, MTA and TAA (96%, with the principal congener being acetic acid as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. D2O (99.9%) was purchased from Wako. Water (18.2 MΩ at 25 °C) was obtained from a Milli-Q Integral 3 Water Purification system.

In a typical experiment, TAA or MTA were mixed with 4:1 H2O/D2O to give a final concentration of 0.36 M or 0.036 M before the solution was placed into an NMR tube under air. A 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer was used for pH 10 reactions and a 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer was used for pH 7 reactions. 0.1 M phosphoric acid was used to adjust the pH of reactions conducted at pH 2.5. The natural pH of a 0.36 M aqueous TAA solution was measured as 2.5, increasing to ~3.8 after complete hydrolysis.

NMR analysis was begun within 10 minutes of preparing the mixtures. 1H NMR experiments were conducted in 5 mm outer diameter borosilicate and constricted NMR tubes (Norell Standard series) using a Bruker Avance III spectrometer. Temperature was held constant during measurements within +/−0.1 °C using a variable temperature unit. The pH of the reactions was monitored by placing aliquots of the reaction mixtures on Sigma-Aldrich Hydrion Brilliant disposable pH sticks, which are accurate to +/−0.1 pH unit. pH was further measured using a Mettler Toledo HM-25R pH meter. Reported pH values were not adjusted for the presence of D2O, which may introduce an inaccuracy of up to ~0.4 pH units at 25 °C29. Ionic strength was not explicitly controlled, but this has been found to have a relatively minor effect on TAA hydrolysis rates28.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Jaguar 8.9 software package purchased from Schroedinger, Inc.30 with the B3LYP/6–31G* basis set. The modified Scaled Quantum Mechanical (SQM) Force Fields method31 was used to scale vibrational frequencies to improve calculations of thermochemical properties which were computed over 273.15 K to 573.15 K. Any remaining errors in absolute Gibbs free energies should be symmetrical and thus be cancelled out in calculation of the reaction ΔG values shown in Table 1. Energy of solvation in water was calculated using the Poisson Boltzmann Solvation model32 with energies of solvation included in the reported free energies. Frequencies less than 10 cm−1 were omitted from energy calculations for consistency with the harmonic approximation used for calculation of thermochemical properties30.

Table 1. Results of DFT calculations to estimate free energies of hydrolysis of TAA and MTA as a function of pH and temperature according to various reaction mechanisms.

| pH | Reaction | ΔGRXN0 °C kJ mol−1 | ΔGRXN100 °C kJ mol−1 | ΔGRXN200 °C kJ mol−1 | ΔGRXN300 °C kJ mol−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | TAA + H2O →AcOH + H2S | −51.7 | −53.1 | −54.4 | −55.9 |

| 7 | TAA− + H2O → AcO− + H2S | −15.2 | −15.2 | −15.1 | −15.0 |

| 10 | TAA− + OH− → AcO− + SH− | −169.4 | −169.2 | −168.7 | −168.2 |

| 2.5 | MTA + H2O → AcOH + CH3SH | −35.3 | −37.6 | −39.8 | −42.0 |

| 7 | MTA + OH− → CH3SH + AcO− | −163.7 | −167.3 | −170.6 | −173.9 |

| 10 | MTA + 2 OH− → AcO− + CH3S− + H2O | −289.1 | −293.3 | −297.2 | −300.8 |

Results

Kinetics of TAA and MTA Hydrolysis

TAA or MTA hydrolysis leads to the formation of acetic acid (CH3COOH or AcOH) and H2S or CH3SH (Equation 1):

|

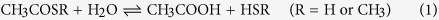

TAA and MTA hydrolysis and equilibrium was examined directly in real time by 1H NMR (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. 1H NMR spectra showing the time evolution of hydrolysis of TAA at 50 °C and pH 2.5 (top) and MTA at 30 °C and pH 10 (bottom).

Peaks were identified by comparison with commercial standards: 1 TAA, 2 acetic acid, 3 MTA, 4 CH3SH. Integrated peak areas were used to determine kinetic parameters.

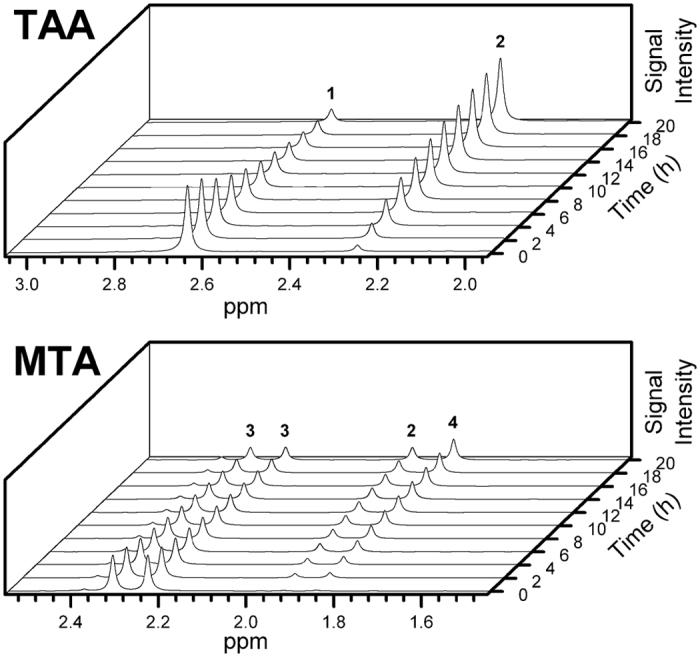

Acetic acid was the only observable product of TAA degradation by 1H NMR. Oxidative coupling to generate disulfides was not observed in any experiment. TAA and MTA hydrolysis was fit to a pseudo-first order kinetic model, which gave rates consistent with those previously measured to within ±9.8%28. Measured TAA and MTA hydrolysis rates and corresponding half-lives as a function of temperature at pH 2.5, 7 and 10 are shown in Fig. 3. Arrhenius plots for these reactions measured between 30 and 160 °C gave activation energies of 71.2 ± 14.6 kJ mol−1 (pH 2.5), 64.2 ± 19.9 kJ mol−1 (pH 7) and 62.9 ± 22.7 kJ mol−1 (pH 10) for TAA. For comparison, Cefola et al.26 determined a value of 82.8 kJ mol−1 between 70 and 90 °C at pH 12.5. Our measured values for MTA between 30 and 100 °C at pH 2.5, 7 and 10 are 62.8 ± 3.2 kJ mol−1, 42.3 ± 14.9 kJ mol−1 and 101.2 ± 16.4 kJ mol−1, respectively.

Figure 3. Arrhenius plots for the measured hydrolysis rates of TAA and MTA as a function of pH based on a pseudo-first order kinetic model.

The speciation of acetic acid, H2S and CH3SH are pH-dependent. At 25 °C the pKa of acetic acid is 4.75, those of H2S are ~7 and >19 ± 2, and that of CH3SH ~10.433,34. Hipkin and Satchell28,35 measured TAA hydrolysis between 40 and 90 °C as a function of pH and ionic strength, and found that acid-catalyzed TAA hydrolysis is expectedly second order at highly acidic conditions.

TAA is relatively unstable under acidic conditions, while MTA is least stable in base, which is explicable by the fact that the pKa of the sulfhydryl group of TAA is 3.7, rendering it less electrophilic above this pH value, and because S2− is a poor leaving group. Under the alkaline (~pH 10), cooler (~40 °C) conditions often favored for origin of life models for off-axis serpentinizing environments, TAA has a half-life of a few years, while that of MTA is a few hours.

It is worth noting that the dielectric constant of water drops by ~20–30% between the lowest and highest temperature points explored here for each compound and set of pH values36, nevertheless the Arrhenius plots are linear over this range.

Thermodynamics of TAA and MTA Hydrolysis

DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G* level were used to obtain Gibbs energies of formation for aqueous TAA, MTA, and their hydrolysis products. These values were then used to calculate the ΔG of hydrolysis for each species between 0 and 300 °C. The change in protonation state of the reactants and products with changing pH was also considered. The results of these calculations are shown in Table 1.

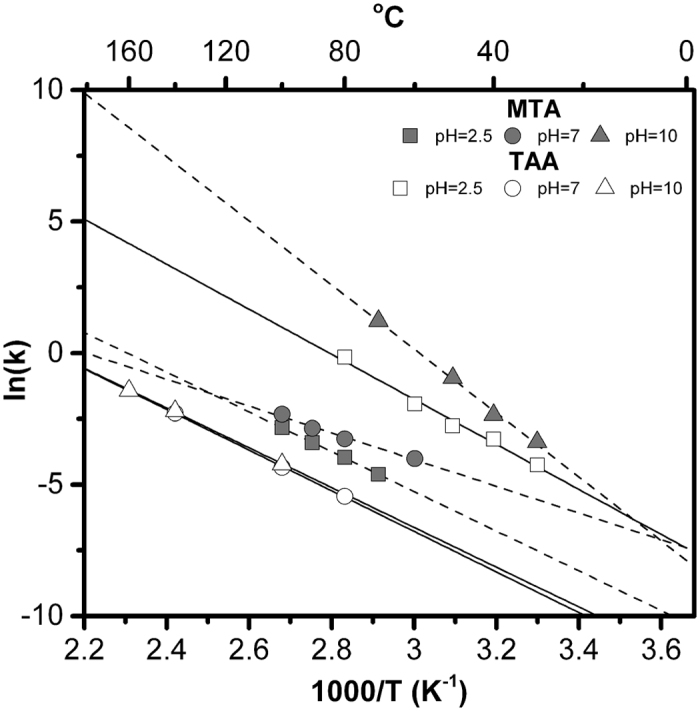

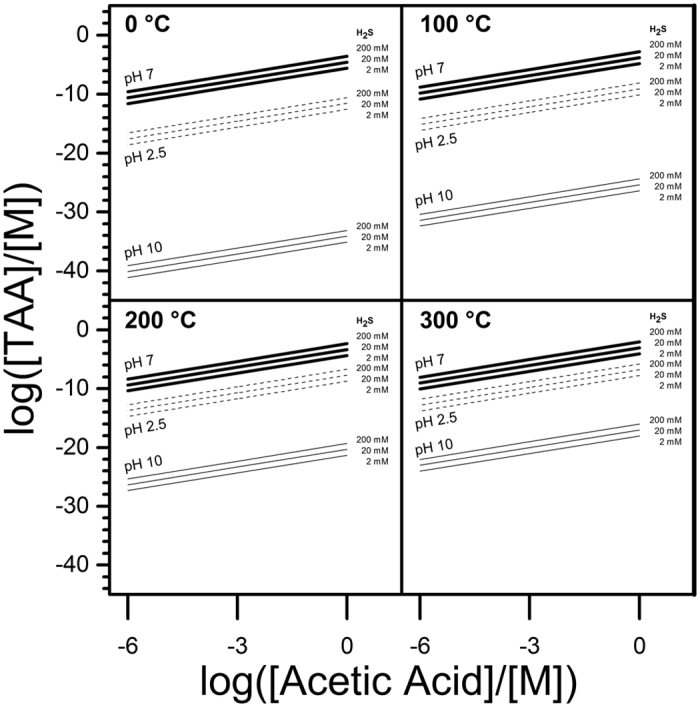

For comparison, some measured free energies of hydrolysis of other simple thioesters are provided here: S-propyl-thioacetate, −32.2 kJ mol−1 37, thiobenzoate, −32.2 kJ mol−1 27, and acetyl CoA, −35.6 kJ mol−1 38. The calculated ΔG of −51.7 kJ mol−1 for TAA at 0 °C and pH 2.5 gives an equilibrium constant for TAA synthesis from acetic acid and H2S of ~1.3 × 10−10, strongly favoring hydrolysis. At higher temperatures the equilibrium constant is somewhat higher: at 300 °C it is ~7.3 × 10−6 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Calculated molar (M) equilibrium TAA concentrations at 0 to 300 °C from varying concentrations of acetic acid and ΣH2S.

Equilibrium ΣH2S concentrations are given above the diagonal isobars.

Given these low equilibrium constants, experimentally tracking the formation of TAA from acetic acid and H2S was experimentally difficult. Attempts were made to measure the formation of TAA and MTA from acetic acid and H2S or CH3SH at pH 2.5 between 30 to 60 °C, however no TAA or MTA was observable, even using very high initial concentrations of acetic acid and H2S or CH3SH. Our estimated 1H NMR detection limit for TAA was ~1 μM, corresponding to a Keq of <5.5 × 10−5 using 1 M acetic acid and 1 M H2S.

As the non-detection of TAA could also have been due to sluggish kinetics, we attempted to estimate the time to equilibration based on the equilibrium constant and hydrolysis rate for pH 2.5. The rate of the forward reaction can be estimated using Equation 2:

|

where k1 and k−1 are the rate constants for TAA formation and TAA hydrolysis, respectively. Using the measured pseudo-first order k−1 rate constant of 1.43 × 10−2 M−1 h−1 at 30 °C and pH 2.5, the forward rate constant (k1) at can be no larger than ~2.8 × 10−10 M−1 hr−1, and were it that high, it would not have been detectable during the time course of our experiments.

The linearity of the Arrhenius plots presented in Fig. 3 indicates a single mechanism under each investigated set of experimental conditions. The linearity of the Arrhenius plots is further strongly indicative of a single rate limiting step. To the extent this is true, the equilibrium approximation presented in Equation 2 is valid. Moreover, the equilibria as calculated are based on the DFT activation energies for each step, which are microscopically reversible, though they may not portray the entire speciation.

Discussion

Implications for TAA and MTA in Prebiotic Chemistry

Modern submarine HT systems are diverse, displaying extreme variability in the composition of their effluent depending on their host mineralogies and hydrodynamics, which have been studied extensively (Table 2 and references provided therein). Effluents range in temperature from several hundred degrees C to the temperature of ambient seawater (~2 °C), and in pH from ~2 to >10 12.

Table 2. Measured physical parameters and concentrations of species relevant to this discussion in various marine HT vents and modern bulk seawater. aRefs 43,45; bRefs 84, 85, 86; cRef. 87, dRefs 39,88, eRef. 59, fRef. 45, −.= not determined, bd = below detection limit as reported.

| Rainbowa,c,d | 9°50′ East Pacific Risea,b,d | Guaymas Basina,e | Lost Citya,d,f | Seawater a,b,c,d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 365 | 221–363 | 172–299 | 94 | 2 |

| pH | 3 | 3.5–4.2 | 4.48–6.09 | 10.2 | 8.1 |

| H2 (mM) | 12–16 | 0.4–1.2 | 0.5–3.3 | 9.1–10.5 | — |

| CO2 (mM) | 20–24 | 8.19–99.3 | 35–51 | <0.19 | 2.36 |

| CO (μM) | 5.1–7.3 | <2 | 0–92 | <1 | — |

| CH4 (mM) | 2 | <0.11 | 44–59 | <1.09 | — |

| Formate (μM) | — | — | — | <140 | bd |

| Acetate (μM) | — | — | 65–365* | 1–35 | bd |

| H2S (mM) | 2–3.3 | 4.6–19.2 | 6.8–8 | 0.07–0.47 | — |

| CH3SH (nM) | 7.7–10.3 | 4–11.4 | 8.1–16,700 | 1.4–1.9 | — |

| SO42− (mM) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1–4 | 53 |

*The acetate detected in Guaymas Basin fluids is attributed to contributions from microbes and thermal cracking of biological material in sediments.

A variety of low molecular weight organic species have been detected in HT vent effluents39,40, including various hydrocarbons, as well as variable amounts of formic acid (Table 2). Formic acid may be derived from the hydration of CO41, which can itself can be derived from the water-gas shift reaction of CO2 and H2, both of which are abundant in some HT settings (Table 2)41.

At least some of the simple organics detected in modern vent effluents are generally agreed to have an abiotic origin based on their isotope systematics, though it is also acknowledged that this signal can be difficult to discern for other organics42,43. Still other organics have been convincingly determined to be of biological origin. For example, the isomer distribution of amino acids detected in several HT vent fluids from the Izu-Bonin Arc strongly suggests a biological origin44.

Despite laboratory experiments demonstrating the production of MTA from CO and CH3SH25, evaluation of modern HT vent effluents has not provided evidence for abiotically derived CH3SH45 or acetate39. CH3OH, the hydroxy analogue of CH3SH, does not appear to be a stable form of carbon under most HT vent conditions, being at best a transient intermediate in the inter-conversion between CO and CH415. Thus the reaction of aqueous H2S and CH3OH is likely not a major contributor to environmentally measured CH3SH concentrations.

Sulfide concentrations in vent fluids are likely governed by concentrations of soluble metal species such as Ni and Fe, among others46. For example the Ksp values at 25 °C for FeS and NiS are 4.9 × 10−18 and 3 × 10−21 respectively47, with these values shifting as a function of temperature and pH. Though concentrations of sulfide (Σsulfide = H2S + SH− + S2−) can be significant in high temperature fluids, these are precipitated rapidly upon cooling due to the formation of metal sulfides48. Thus Σsulfide speciation in modern HT systems has been measured variably between ~0 and a maximum near 20 mM (Table 2). In off-axis serpentinizing vent systems such as Lost City, sulfide concentrations are typically much lower, often less than 1 mM (Table 2) and the majority of S is often found in the form of sulfate, despite the fact that these vents often discharge considerable amounts of dissolved H245.

With regard to the propensity of HT vent chemistry to produce organics beyond the simple hydrocarbons which may be produced in trace amounts in such systems43, it is worth noting that HT systems chemistry may be self-regulating in many respects. High H2 systems, which may contain large amounts of CH4, may inherently limit the production of higher hydrocarbons due to equilibria such as those obtained in Equation 349.

|

The estimated ΔrG′° for this reaction is −68.9 ± 14.2 kJ mol−1 50, giving Keq values of ~1.2 × 1012, 4.4 × 109 and 4.0 × 107 at 25, 100 and 200 °C, respectively.

Likewise, high CO2/reduced Fe systems are limited in their ability to supply H2 or reduced C (including CO, which appears to be the active species for Fischer Tropsch Type synthesis)16 due to the precipitation of siderite (FeCO3)51. Thus, fluids with high dissolved inorganic carbon limit the ability of Fe2+ to serve as a reducing agent, even though high concentrations of C species might allow for escape from the kinetic limitations of forming higher C-species.

If the upper mantle had already largely reached its modern oxidation state by 4.35 Ga, as appears to be true from recent measurements of rare earth elements in zircons52 then modern HT vent chemistry is likely similar to what one could expect for early Earth geochemistry12,53, though the composition of bulk seawater may have been markedly different. The heat flux on the primitive Earth was likely somewhat higher, making mean oceanic circulation times through seafloor HT vent systems on the whole shorter54, nevertheless the residence times of fluids at high temperatures would still be on average long enough to ensure equilibration of seawater with host mineralogies. There is little evidence that mantle-derived rocks have ever contained markedly higher C or S concentrations55,56, though there have been significant changes in bulk ocean water composition over time57. pH and Fe, C, and S species concentrations in the oceans between 3.5 Ga and 4.4 Ga are poorly constrained due the lack of corroborating geological evidence.

Nevertheless, high- and low-end estimates for the concentrations of some species can be broadly constrained. Sulfide concentrations in the bulk Archaen ocean (~4-2.5 Ga) have been suggested to have been in the low mM range48, which is similar to concentrations observed in modern HT vent fluids (Table 2).

For the sake of subsequent calculations, we will assume a generous 20 mM sulfide concentration for vent fluid or the bulk ocean, acknowledging that this value may be overestimated by orders of magnitude depending on the exact geochemical setting under consideration. Due to metal sulfide solubility product constraints, these values are unlikely to be underestimated in any environment.

Equilibrium TAA concentrations would be limited by H2S concentrations, MTA concentrations similarly by CH3SH concentrations. Except under strongly acidic conditions, TAA is generally more stable than MTA, but TAA is undoubtedly more plausible simply due to the likely much higher abundance of H2S, which is more abundant than CH3SH in modern HT vent fluids by a factor of 1000 or more (Table 2). It is difficult to envision a geochemical setting in which H2S concentrations are lower than CH3SH concentrations, due to the equilibria involved in making CH3SH in the first place58.

Figure 4 shows estimates for maximal equilibrium concentrations of TAA in various HT settings, as a function of possible ΣH2S and Σacetate concentrations, and using the Keq values for TAA formation derived from the calculated free energy values in Table 1. Much of the area shown in this figure represents parameter combinations which are unlikely to be attainable in natural HT systems. Measured concentrations (Table 2) of acetate and H2S in fluids from Lost City39 and hydrothermally altered biologically organic-enriched sediments from Guaymas basin59 would yield TAA concentrations of 1.4 × 10−49 and 2.1 × 10−11 M, respectively. These rough equilibrium calculations do not take into account potential competing side reactions (which could only lower these values) and mineral or other types of catalysis (which in principle would only speed the time to equilibration), nevertheless the equilibria cannot be high due to the factors discussed above.

Given the second order rate and yield dependencies of condensation reactions, which typically decline inversely as a function of reactant concentrations, these concentrations are very low for the sake of performing more complex organic chemistry in HT environments. In our study, even examining the behavior of TAA or MTA concentrated far beyond what is plausible in natural marine environments, we note that only the predicted hydrolysis products are observed by NMR.

Huber and Wächtershäuser25 reported ~0.5% acetate yields based on input CH3SH (8 mM) in the presence of 350 mM CO. This is ~500 times and ~3700 times the highest CH3SH and CO concentrations respectively measured to date in a natural vent fluid45. All isotopic measurements to date suggest that acetate detected in HT vent fluids is derived from biological material39 despite being predicted to form abiotically under HT conditions13.

Reduced carbon species in modern HT vent fluids have not been measured outside of the mM range (Table 2), and it is clear that in some cases, for example the Guaymas Basin, high organic contents are due to the liberation of biological material from sediments59. These fluids contain the highest concentrations of acetate measured in submarine HT fluids to date, but acetate is a common component of naturally cracked petroleum60.

The redox equilibrium between H2 released by serpentinization reactions and one-C species can be constrained. C-C bond forming reactions are most kinetically favorable from formate/CO and as would be expected the equilibrium between CO and formate, a simple hydration, is obtained rapidly, while that between CO2 and CH4 is not15. Thus CO (or its hydrate) is likely the limiting reagent for higher hydrocarbon formation.

Previous models of HT origins of life have appealed to MTA as opposed to TAA based on experiments by Heinen and Lauwers61 and Huber and Wächtershäuser25 in which CH3SH and MTA were prepared from very high concentrations of reagents. Huber and Wächtershäuser’s25 demonstrated synthesis of acetate from CH3SH, CO, and NiSO4 or various metal sulfides was proposed to proceed through MTA as an intermediate. However, the conditions of the experiment are of questionable geochemical relevance: for example, 160 mM Na2S was employed, which is much higher than that observed in any extant natural system (Table 2).

Concentration processes would be necessary for the prebiotic synthesis of these compounds. Potential concentration mechanisms such as thermophoresis62 deserve much further experimental investigation in this context. This has become a major touchstone of models for the origin of life in HT vent systems12,63, though to date little evidence has been presented which suggests that small molecules such as TAA can be concentrated by several orders of magnitude by this mechanism in geochemical settings.

Dissolved Fe2+ catalyzes TAA hydrolysis, while solid FeS had no effect under the same conditions64. Nevertheless, mineral surface catalysis and catalysis by dissolved organic and/or inorganic species are unlikely to solve these instability problems. TAA and MTA hydrolyze rapidly, and their formation equilibria are very low, thus little is gained by achieving equilibrium more rapidly through catalysis, and for group transfer from very low concentration transient species the resulting acylates would have to be extremely stable to accumulate.

The effect of pH on the equilibrium constants for TAA derivatives may be attributable to pKa differences between the reacting acid and thiol species, as has been suggested in the case of amide bond formation65. Simply based on the pKa differences between H2S (~7.0) and CH3SH (~10.4) with acetic acid (~4.8) at 25 °C, one would expect the Keq for TAA to be significantly higher than for MTA, which is concordant with our DFT calculations. For reference the pKa’s of ethane thiol (~10.6) and butane thiol (~10.5) are fairly close to those reported for CoASH (~9.6–10)33, thus there is no strong reason to think that higher thiols would have significantly different Keq values, and the abundances of higher thiols can reasonably be expected to be much lower.

While the pH of vent fluids has probably always been locally controlled, the pH of the prebiotic oceans remains uncertain. The best geochemists have been able to infer is a minimum pH for the oceans, which is on the order of 5–666, though some have argued for a pH closer to neutral67. A full explanation for the pH early oceans must account for buffering systems in addition to carbonate, for example marine clays68, and there is a general need to balance species such as Ca2+ and Mg2+. It is not clear that a high, neutral or low pH environment bulk ocean is necessarily preferable for the origin of life, though in scenarios which invoke TAA or MTA, each has significant consequences.

Acidic oceans do not seem to be preponderant on icy worlds in our solar system where measurement has been possible, for example on Enceladus, as inferred from mass spectrometry of plume ejecta69. The presence of significant amounts of dissolved ammonia has been implicated as necessary to render many icy moons’ subsurface water reservoirs liquid70. The early phases of Mars’ evolution, by most accounts when Mars was most likely to have hosted surface oceans, seem to be consistent with slightly basic to circum-neutral pH, though it appears that subsequent planetary evolution drove Mars’ surface into a more acidic regime71.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to examine every conceivable reaction mechanism which could lead to thioesters in hydrothermal environments. There are other routes by which TAA derivatives could be reasonably abiotically synthesized. For example the sulfhydrolysis of acetonitrile (ACN) with H2S to give TAA10. ACN is a product of abiotic atmospheric synthesis from reducing gas mixtures72. The primary intermediate of the reaction of H2S with ACN, thioacetamide, is also unlikely to accumulate in most environments, degrading principally to TAA under basic conditions, and acetamide under acidic ones73.

The addition of thiols to aldehydes followed by oxidation could also yield thioesters. However, this ignores the problem of thiol concentration already discussed and would require the presence of significant concentrations of aldehydes which are unlikely to be stable to the temperature and redox conditions prevailing in HT environments (see for example Nagai et al.74 and Schulte and Shock75; to our knowledge, there have been no reports to date of significant amounts of abiotic aldehydes in natural submarine HT environments). In any event the products would still suffer from the extreme hydrolytic instability demonstrated here. Such a mechanism may be more favorable in a low-temperature evaporative environment, but seems difficult in the context of a flow-through, elevated temperature marine environment.

Conclusions

The origin of life almost certainly occurred during a period for which little is left of the primary geological record. Unfortunately this means a great deal is inferred in many scenarios. Fortunately, a good deal can be extrapolated based on what is measurable in the laboratory. Modern organisms are obviously capable of internally generating high-energy compounds such as thioesters under relatively extreme conditions by coupling their synthesis to other cellular energy-dissipating reactions, and shunting them for use in other biochemical pathways before they have time to decompose. The goal of this paper is to examine the abiotic generation and behavior of thioester derivatives in natural settings and by doing so, identify constraints for prebiotic chemistry and origin of life models. Until thioesters were capable of being generated at reasonable steady states by relatively complex chemical assemblages (e.g. systems on the continuum from chemical networks to fully recognizable biological systems), it is unlikely such compounds could have contributed to the origin or maintenance of such assemblages, except possibly in certain specialized environments as discussed below. TAA and MTA differ significantly in terms of their stability and reactivity as a function of pH and temperature, though both are implausible prebiotic reagents for different reasons in different contexts.

The variety of schemes in which TAA and MTA are implicated prompted this investigation. The large free energy changes for the hydrolysis of TAA and MTA have contributed to the notion of their potential utility as acetyl-CoA analogues in prebiotic chemistry6,7,25,63. Thioesters were implicated in the origin of life after the discovery of the importance of CoA in biochemistry and non-ribosomal peptide synthesis7,76. Early models were not generally tied to any particular geochemical setting, it was merely pointed out that these compounds were sufficiently energetic, and possibly stable enough, to allow for spontaneous group transfer, and that analogue compounds play important roles in contemporary biochemistry. More recent models suggest that TAA and thioesters are vestigial links between geochemical processes and the origin of intermediary metabolism, for example as reagents for a primitive Wood-Ljungdahl-like pathway2,6,18, based on the chemistry which may occur in natural settings and the conjecture that inorganic ligands used in contemporary biological systems, such as FeS clusters, are derived cognates of naturally occurring minerals2,6,77, i.e., that life originally depended on specific environmental chemical pathways, which it gradually coopted.

In examining the kinetics of thioester exchange reactions, Whitesides and coworkers concluded that there was no a priori reason on the basis of the kinetics of hydrolysis for blanket skepticism or rejection of theories that invoke thioesters as molecules of prebiotic importance17. However, the kinetic and thermodynamic considerations presented here highlight difficulties which may exclude thioesters from consideration in many prebiotic contexts.

In considering the plausibility of the existence of any given species, and its possible concentrations, it is useful to adopt a systems-based analysis. The sources and sinks of species are crucial considerations, as are the temporal dynamics of material transport, and chemical kinetics and equilibria in geological settings.

It is difficult to categorically state that some species could have been present in any given concentration in any given environment on the primitive Earth, especially since there may have existed gradients of environmental parameters where many combinations of pH, temperature, and speciation could have been juxtaposed for variable amounts of time78. Nevertheless, one can ask questions about what combination of factors would have allowed for a set of conditions to have been common or even transiently achievable.

The instabilities and difficulty of synthesis of various organic compounds have been used previously to argue against the likelihood of various compounds’ accumulation and involvement in the origin of life in certain settings79. TAA derivatives are considerably less stable than most of the compounds examined in these papers and must be considered critically in that light, though they are not the most unstable compounds considered in HT settings. For example, acetylphosphate has a half-life of only ~1.2 hours between pH 2.7 and 7.7 even at 39 °C80.

A number of extant organisms carry out reactions which initially fix CO via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, ultimately yielding acetyl-CoA. However, while these CoA analogs could conceivably be generated in very low steady-states abiotically, they may be unlikely feedstocks for the origin of life or primitive biology. In this study, we reacted extremely high concentrations of TAA or MTA, and found that there are no products aside from the hydrolytic ones, thus there may be relatively few reactions by which acetate equivalents could be donated by TAA or its derivatives, aside from acetyl group transfer (although TAA is also known to act as an S nucleophile to alkenes81), and then only in settings which allowed for considerably higher concentrations of these compounds than HT vents are likely to provide. The flux of energy made available by these compounds would likewise be insignificant compared to that available from other compounds such as CO and H2.

Small equilibrium amounts of TAA derivatives obtained by quenching of high temperature fluids could be produced in HT vent settings and conducted to the bulk ocean, and then concentrated by evaporation to give higher concentrations of TAA, but such a mechanism requires the site of their use to be an evaporative environment rather than the vent itself.

Lastly, since these compounds are such important reagents in so many HT origin of life schemes, their remarkable instability under typical HT environment conditions suggests estimates of the ubiquity of suitable environments for the origin of life in and beyond our solar system may be somewhat overestimated82,83, if these compounds are indeed crucial for jump-starting early metabolism.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chandru, K. et al. The Abiotic Chemistry of Thiolated Acetate Derivatives and the Origin of Life. Sci. Rep. 6, 29883; doi: 10.1038/srep29883 (2016).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) for funding during the preparation of this manuscript. This project was also supported by the ELSI Origins Network (EON), which is supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. This work was also supported by a JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Hadean Bioscience.”

Footnotes

Author Contributions K.C., A.G. and H.J.C. performed the experiments. K.C. and A.G. performed the chemical analysis. C.B. performed the DFT calculations. K.C., A.G., C.B., M.A. and H.J.C. prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Corliss J., Baross J. & Hoffman S. An hypothesis concerning the relationship between submarine hot springs and the origin of life on Earth. Oceanol. Acta 4 Supplement, 59–69 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Wächtershäuser G. Groundworks for an evolutionary biochemistry - the iron sulfur world. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 58, 85–201 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. J., Daniel R. M., Hall A. J. & Sherringham J. A. A hydrothermally precipitated catalytic iron sulphide membrane as a first step toward life. J. Mol. Evol. 39, 231–243, doi: 10.1007/bf00160147 (1994). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cody G. Transition metal sulfides and the origins of metabolism. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 32, 569–599 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Wächtershäuser G. Evolution of the first metabolic cycles. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 200–204 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. J. & Martin W. The rocky roots of the acetyl-CoA pathway. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 29, 358–363, doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.05.007 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C. Clues from present-day biology: the thioester world. In The Molecular Origins of Life (ed. Brack A.) 219–236 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Huber C. & Wächtershäuser G. Peptides by activation of amino acids with CO on (Ni,Fe)S surfaces: Implications for the origin of life. Science 281, 670–672, doi: 10.1126/science.281.5377.670 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan W. J. Uracil-catalyzed synthesis of acetyl phosphate: A photochemical driver for protometabolism. Chem Bio Chem. 11, 383–387, doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900433 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R. & Orgel L. E. Oxidative acylation using thioacids. Nature 389, 52–54, doi: 10.1038/37944 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T., Yabushita Y. & Tabushi I. Amino acid synthesis through biogenetic-type CO2 fixation. Nature 256, 60–61 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W., Baross J., Kelley D. & Russell M. J. Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life. Nat. Rev. Micro. 6, 805–814 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shock E. L. & Schulte M. D. Organic synthesis during fluid mixing in hydrothermal systems. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 103, 28513–28527, doi: 10.1029/98JE02142 (1998). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe A. D., Newton G. L. & Miller S. L. A possible prebiotic synthesis of pantetheine, a precursor to coenzyme A. Nature 373, 683–685, doi: 10.1038/373683a0 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seewald J. S., Zolotov M. Y. & McCollom T. Experimental investigation of single carbon compounds under hydrothermal conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 446–460, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2005.09.002 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCollom T. M., Lollar B. S., Lacrampe-Couloume G. & Seewald J. S. The influence of carbon source on abiotic organic synthesis and carbon isotope fractionation under hydrothermal conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 2717–2740, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.02.008 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher P. J., Snyder P. W., Bohall B. R. & Whitesides G. M. The relative rates of thiol–thioester exchange and hydrolysis for alkyl and aryl thioalkanoates in water. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres 41, 399–412 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöchl E., Keller M., Wächtershäuser G. & Stetter K. O. Reactions depending on iron sulfide and linking geochemistry with biochemistry. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 8117–8120 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morowitz H. J. A theory of biochemical organization, metabolic pathways, and evolution. Complexity 4, 39–53, doi: (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A. L. & Orgel L. E. Formation of peptides From glycine thioesters. J. Mol. Evol. 13, 193–202 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R., Loganathan M. & Shantha M. S. A review of the water gas shift reaction kinetics. Int. J. Chem. Reactor Eng. 8 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Jöns N. & Bach W. In Encyclopedia of Marine Geosciences (eds. Harff J., Meschede M., Petersen S. & Thiede J.) Ch. 119-1, 1–12 (Springer Netherlands, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cody G. D. et al. Geochemical roots of autotrophic carbon fixation: hydrothermal experiments in the system citric acid, H2O-(±FeS)−(±NiS). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 3557–3576, doi: 10.1016/s0016-7037(01)00674-3 (2001). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Yang B., Qu Y., Liu X. & Su W. FeS/S/FeS2 redox system and its oxidoreductase-like chemistry in the iron-sulfur world. Astrobiology 11, 471–476, doi: 10.1089/ast.2011.0624 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C. & Wächtershäuser G. Activated acetic acid by carbon fixation on (Fe,Ni)S under primordial conditions. Science 276, 245–247, doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.245 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cefola M., Peter S. S., Gentile P. S. & Celiano R. A. V. Rate of hydrolysis of thiolacetic acid in basic solutions. Talanta 9, 537–540, doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(62)80125-8 (1962). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. A. & Yates K. Mechanistic studies in strong acids. VIII. Hydrolysis mechanisms for some thiobenzoic acids and esters in aqueous sulfuric acid, determined using the excess acidity method. Can. J. Chem. 60, 3061–3070, doi: 10.1139/v82-438 (1982). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hipkin J. & Satchell D. P. N. The spontaneous and acid-catalysed hydrolysis of thiolcarboxylic acids. Tetrahedron 21, 835–842, doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(65)80017-5 (1965). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krżel A. & Bal W. A formula for correlating pKa values determined in D2O and H2O. J. Inorg. Biochem. 98, 161–166 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochevarov A. D. et al. Jaguar: A high-performance quantum chemistry software program with strengths in life and materials sciences. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 113, 2110–2142, doi: 10.1002/qua.24481 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J., Jarzecki A. A. & Pulay P. Direct scaling of primitive valence force constants: an alternative approach to scaled quantum mechanical force fields. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1412–1424 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V., Olson R. M., Kelly C. P., Cramer C. J. & Truhlar D. G. Self-consistent reaction field model for aqueous and nonaqueous solutions based on accurate polarized partial charges. J. Chem. Theory Comp. 3, 2011–2033 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin D. D. Ionisation Constants of Inorganic Acids and Bases in Aqueous Solution. (Elsevier Science, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. N., Centelles M. N. & Moore K. P. Making and working with hydrogen sulfide: The chemistry and generation of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and its measurement in vivo: a review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 1346–1353, doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipkin J. & Satchell D. P. N. 189. Acylation. Part XV. The spontaneous and acid-catalysed hydrolysis of diacetyl sulphide. J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed), 1057–1062, doi: 10.1039/JR9650001057 (1965). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer D. G. & Wang P. The Dielectric Constant of Water and Debye‐Hückel Limiting Law Slopes. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 19, 371–411 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Jencks W. P., Cordes S. & Carriuolo J. The free energy of thiol ester hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 235, 3608–3614 (1960). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guynn R. W., Webster L. T. & Veech R. L. Equilibrium constants of the reactions of acetyl coenzyme A synthetase and the hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate to adenosine monophosphate and inorganic pyrophosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 3248–3254 (1974). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang S. Q., Butterfield D. A., Schulte M., Kelley D. S. & Lilley M. D. Elevated concentrations of formate, acetate and dissolved organic carbon found at the Lost City hydrothermal field. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 941–952, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2009.10.045 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holm N. G. & Charlou J. L. Initial indications of abiotic formation of hydrocarbons in the Rainbow ultramafic hydrothermal system, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 191, 1–8 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- McCollom T. M. & Seewald J. S. Experimental constraints on the hydrothermal reactivity of organic acids and acid anions: I. Formic acid and formate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3625–3644 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q., Sherwood Lollar B., Horita J., Lacrampe-Couloume G. & Seyfried W. E. Jr Abiotic formation of hydrocarbons under hydrothermal conditions: Constraints from chemical and isotope data. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 1982–1998, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2007.01.022 (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proskurowski G. et al. Abiogenic hydrocarbon production at Lost City hydrothermal field. Science 319, 604–607, doi: 10.1126/science.1151194 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano Y. et al. Vertical distribution of amino acids and chiral ratios in deep sea hydrothermal sub-vents of the Suiyo Seamount, Izu-Bonin Arc, Pacific Ocean. Org. Geochem. 35, 1105–1120, doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2004.06.007 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves E. P., McDermott J. M. & Seewald J. S. The origin of methanethiol in midocean ridge hydrothermal fluids. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5474–5479 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Damm K. L. Seafloor hydrothermal activity: black smoker chemistry and chimneys. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 18, 173–204 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Haynes W. M. & Lide D. R. Handbook of chemistry and physics. Vol. 92 (CRC Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. C. G. & Brimblecombe P. Iron and sulfur in the pre-biologic ocean. Precambrian Res. 28, 205–222, doi: 10.1016/0301-9268(85)90031-2 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollom T. M. In Carbon in Earth Vol. 75 Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry (eds Hazen R. M., Jones A. P. & Baross J. A.) 467–494 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Flamholz A., Noor E., Bar-Even A. & Milo R. eQuilibrator—the biochemical thermodynamics calculator. Nuc. Acids Res. 40, D770–D775 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesli R. A., Beard B. L. & Johnson C. M. Experimental determination of Fe isotope fractionation between aqueous Fe(II), siderite and “green rust” in abiotic systems. Chem. Geol. 211, 343–362, doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.07.002 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trail D., Watson E. B. & Tailby N. D. The oxidation state of Hadean magmas and implications for early Earth’s atmosphere. Nature 480, 79–82 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baross J. & Hoffman S. Submarine hydrothermal vents and associated gradient environments as sites for the origin and evolution of life. Origins Life Evol. B. 15, 327–345, doi: 10.1007/BF01808177 (1985). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazcano A. & Miller S. L. How long did it take for life to begin and evolve to cyanobacteria? J. Mol. Evol. 39, 546–554 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen P. B. & Manning C. E. Reevaluating carbon fluxes in subduction zones, what goes down, mostly comes up. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E3997–E4006 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D. E. The evolution of the Earth surface sulfur reservoir. Am. J. Sci. 304, 839–861 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Holland H. D. The chemical evolution of the atmosphere and oceans (Princeton University Press, 1984). [Google Scholar]

- Schulte M. D. & Rogers K. L. Thiols in hydrothermal solution: standard partial molal properties and their role in the organic geochemistry of hydrothermal environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 1087–1097, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2003.06.001 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martens C. S. Generation of short chain acid anions in hydrothermally altered sediments of the Guaymas Basin, Gulf of California. Appl. Geochem. 5, 71–76, doi: 10.1016/0883-2927(90)90037-6 (1990). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky A. J., Maiella P. G. & Brill T. B. Spectroscopy of hydrothermal reactions 13. Kinetics and mechanisms of decarboxylation of acetic acid derivatives at 100−260 °C under 275 bar. J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 4253–4260, doi: 10.1021/jp984122d (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen W. & Lauwers A. M. Organic sulfur compounds resulting from the interaction of iron sulfide, hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide in an anaerobic aqueous environment. Origins Life Evol. Biospheres 26, 131–150, doi: 10.1007/bf01809852 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baaske P. et al. Extreme accumulation of nucleotides in simulated hydrothermal pore systems. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9346–9351, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609592104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke W. & Russell M. J. Beating the acetyl coenzyme A-pathway to the origin of life. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London B: Biol. Sci. 368, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0258 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. Sulfur and the Origins of Life. Master of Science thesis, University of Canterbury, (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Ulijn R. V., Moore B. D., Janssen A. E. & Halling P. J. A single aqueous reference equilibrium constant for amide synthesis–hydrolysis. J. Chem. Soc. Perk. Trans. 2, 1024–1028 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. W. & Mackenzie F. T. Hadean ocean carbonate geochemistry. Aquat. Geochem. 4, 301–319, doi: 10.1023/a:1009632230875 (1998). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep N. H. The Hadean-Archaean environment. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2, a002527 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillén L. G. The ocean as a chemical system. Science 156, 1189–1197, doi: 10.1126/science.156.3779.1189 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glein C. R., Baross J. A. & Waite J. H. The pH of Enceladus’ ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 162, 202–219 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Hussmann H., Sohl F. & Spohn T. Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects. Icarus 185, 258–273, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustard J. F. et al. Hydrated silicate minerals on Mars observed by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter CRISM instrument. Nature 454, 305–309 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toupance G., Raulin F. & Buvet R. Formation of prebiochemical compounds in models of the primitive Earth’s atmosphere. Origins Life 6, 83–90 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal D. & Taylor T. I. A study of the mechanism and kinetics of the thioacetamide hydrolysis reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79, 2684–2690, doi: 10.1021/ja01568a007 (1957). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Morooka S., Matubayasi N. & Nakahara M. Mechanisms and kinetics of acetaldehyde reaction in supercritical water: Noncatalytic disproportionation, condensation, and decarbonylation. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 11635–11643, doi: 10.1021/jp046117h (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte M. D. & Shock E. L. Aldehydes in hydrothermal solution: Standard partial molal thermodynamic properties and relative stabilities at high temperatures and pressures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 3835–3846, doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(93)90337-V (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipmann F. Attempts to map a process evolution of peptide biosynthesis. Science 173, 875–884, doi: 10.1126/science.173.4000.875 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody G. et al. Assaying the catalytic potential of transition metal sulfides for abiotic carbon fixation Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 2185–2196 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Holm N. G. & Andersson E. In The Molecular Origins of Life: Assembling the Pieces of the Puzzle (ed Brack Andre) (Cambridge University Press, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- White R. H. Hydrolytic stability of biomolecules at high temperatures and its implication for life at 250 °C. Nature 310, 430–432 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland D. E. Effect of catalysts on the hydrolysis of acetyl phosphate. Nucleophilic displacement mechanisms in enzymatic reactions 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 74, 2286–2292, doi: 10.1021/ja01129a035 (1952). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattos M. & Bernini R. B. The reaction of (R)-limonene with S-thioacids. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 18, 1068–1072 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. J. et al. The drive to life on wet and icy worlds. Astrobiology 14, 308–343 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaves H. J. 2nd & Chalmers J. H. Extremophiles may be irrelevant to the origin of life. Astrobiology 4, 1–9, doi: 10.1089/153110704773600195 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douville E. et al. The rainbow vent fluids (36°14′N, MAR): the influence of ultramafic rocks and phase separation on trace metal content in Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal fluids. Chem. Geol. 184, 37–48, doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(01)00351-5 (2002). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von Damm K. L. et al. Chemistry of submarine hydrothermal solutions at 21°N, East Pacific Rise. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 49, 2197–2220, doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(85)90222-4 (1985). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welhan J. A. & Craig H. In Hydrothermal Processes at Seafloor Spreading Centers Vol. 12 NATO Conference Series (eds Rona P. A., Boström K., Laubier L. & Smith K. L. Jr.) Ch. 17, 391–409 (Springer US, 1983). [Google Scholar]

- Kelley D. S. et al. An off-axis hydrothermal vent field near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at 30°N. Nature 412, 145–149 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tivey M. K. Generation of seafloor hydrothermal vent fluids and associated mineral deposits. Oceanogr. 20, 50–65, doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2007.80. (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]