Abstract

Aims

To understand how perceived law enforcement policies and practices contribute to the low rates of utilization of opioid agonist therapies (OAT) among people who inject drugs (PWIDs) in Ukraine.

Methods

Qualitative data from 25 focus groups (FGs) with 199 opioid-dependent PWIDs in Ukraine examined domains related to lived or learned experiences with OAT, police, arrest, incarceration, and criminal activity were analyzed using grounded theory principles.

Findings

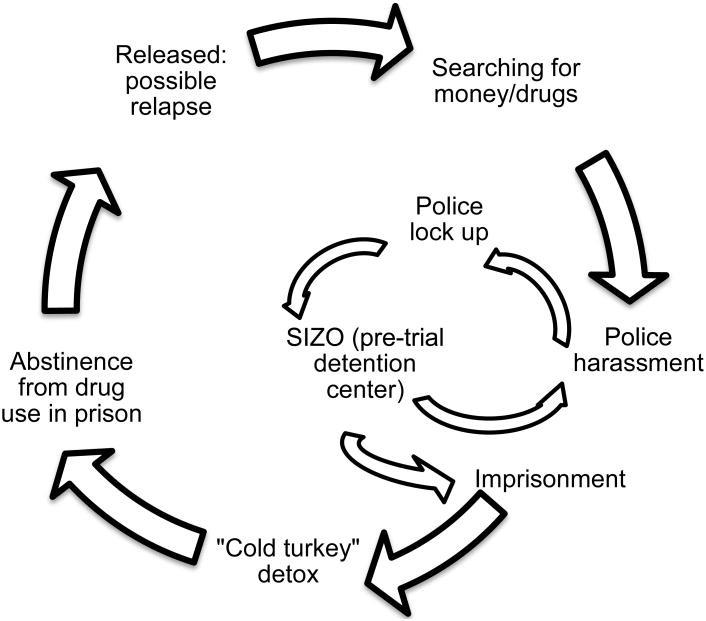

Most participants were male (66%), in their late 30s, and previously incarcerated (85%) mainly for drug-related activities. When imprisoned, PWIDs perceived themselves as being “addiction-free”. After prison-release, the confluence of police surveillance, societal stress contributed to participants' drug use relapse, perpetuating a cycle of searching for money and drugs, followed by re-arrest and re-incarceration. Fear of police and arrest both facilitated OAT entry and simultaneously contributed to avoiding OAT since system-level requirements identified OAT clients as targets for police harassment. OAT represents an evidence-based option to ‘break the cycle’, however, law enforcement practices still thwart OAT capacity to improve individual and public health.

Conclusion

In the absence of structural changes in law enforcement policies and practices in Ukraine, PWIDs will continue to avoid OAT and perpetuate the addiction cycle with high imprisonment rates.

Keywords: Addiction, opioid agonist treatment, people who inject drugs, opioid substitution treatment, qualitative research, police harassment, addiction trajectories, Ukraine

Introduction

Globally there are an estimated 12.7 million people who inject drugs (PWIDs) (UNAIDS, 2014), including 310, 000 PWIDs in Ukraine (Berleva et al., 2012). Ukraine's volatile epidemic among PWIDs with high HIV prevalence has continued to rise after Ukraine's rapid social and economic changes since gaining independence in 1991 (Poznyak, Pelipas, Vievski, & Miroshnichenko, 2002). The tragic political, social and military conflict currently unraveling in Ukraine perpetuates an environment for further growth of drug markets that fuel illegal drug use and HIV risk (Filippovych, 2015; Kazatchkine, 2014).

The clinical understanding that opioid use disorders are chronic, relapsing medical conditions (Goldstein & Herrera, 1995; Grella & Lovinger, 2011; Hser, Anglin, & McGlothlin, 1987; Maddux & Desmond, 1992; O'Donnell, 1964; Vaillant, 1970) enables the research community to recognize and follow movements along addiction trajectories without redundant distraction for moralization. Law enforcement policies and perceptions, however, in many places are often slower to align with contemporary mainstream views on addiction. For example, the so-called “war on drugs” has resulted in many national drug control policies that focus on law enforcement against drug use and disruption of the supply chain. People who use drugs often suffer from collateral damage brought by these practices in the form of basic human rights violations consisting of harassment, detention, and coercion (Bluthenthal, Lorvick, Kral, Erringer, & Kahn, 1999; Singer, 2006a, 2006b; Singer, Scott, Wilson, Easton, & Weeks, 2001; UNAIDS, 2014), which undermine social networks and accelerate HIV risk (Maru, Basu, & Altice, 2007). Moreover, widespread punitive national responses to PWIDs also define therapeutic trajectories (Raikhel & Garriott, 2013) and result in higher morbidity and mortality (Azbel, Wickersham, Grishaev, Dvoryak, & Altice, 2013, 2014; Drucker, 2002; Maru et al., 2007), decreased effectiveness of HIV prevention and treatment programs (Azbel et al., 2014; Booth et al., 2013) and ineffective application of public resources (Burns, 2014; Sabet, 2014). While there have been examples of clashes between evidence-based addiction treatments and punitive approaches resulting in opioid agonist therapy (OAT) expansion with either methadone or buprenorphine maintenance globally (Cohen, 2010b; Degenhardt et al., 2014), drug policies favoring police interdiction and incarceration over community-based OAT have resulted in high incarceration rates in many countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) (Walmsley, 2014). Consequently in many of these countries, people with psychiatric and substance use disorders (SUD) and people at risk for or living with HIV (PLH) interface with the penal system (Vagenas et al., 2013), including the police (Izenberg et al., 2013; Mimiaga et al., 2010). Treatment of SUDs in EECA, mostly as vestiges of antiquated influences from the former Soviet Union, has been restricted more by moral biases and prejudices than by scientific evidence (Bojko, Dvoriak, & Altice, 2013; Cohen, 2010a, 2010b). Without evidence-based interventions (EBIs) (Fazel & Baillargeon, 2011), detained persons often engage in risky HIV behaviors both within prison and post-release (Izenberg et al., 2014; Rhodes, 2002), creating a high-risk environment.

Both OAT and antiretroviral therapy (ART), when adequately scaled, are crucial EBIs. OAT is effective for both primary (reducing injection risks) (Altice, Kamarulzaman, Soriano, Schechter, & Friedland, 2010; Altice et al., 2006; Metzger et al., 1993), and secondary (increasing ART access and adherence) (Altice et al., 2011; Lucas et al., 2010; Palepu et al., 2006; Uhlmann et al., 2010) prevention and viral suppression (Altice et al., 2011; L. Gowing, Farrell, Bornemann, Sullivan, & Ali, 2011; L. R. Gowing, Hickman, & Degenhardt, 2013; Lawrinson et al., 2008; Palepu et al., 2006) as well as HIV prevention within prison (Haig, 2003) and post-release (Kinlock, Gordon, Schwartz, Fitzgerald, & O'Grady, 2009; Springer, Chen, & Altice, 2010; Springer, Qiu, Saber-Tehrani, & Altice, 2012). Viral suppression is associated with reduced HIV transmission to sexual and injecting partners (M. S. Cohen et al., 2011; Donnell et al., 2010; Montaner, 2013; Montaner et al., 2014; Wood, Milloy, & Montaner, 2012). Mathematical modeling, moreover, confirms that scaling up both OAT and ART is the most effective HIV prevention strategy in EECA (Alistar, Owens, & Brandeau, 2011; Vickerman et al., 2014) with OAT being the most cost-effective strategy (Alistar et al., 2011).

Police harassment practices toward PWIDs, though, have been reported as a substantial contributor to the suboptimal OAT scale-up (Bachireddy et al., 2014; Izenberg et al., 2014; Polonsky et al., 2015; Zabransky, Mravcik, Talu, & Jasaitis, 2014) both through preventing PWIDs from initiating treatment and creating barriers to retention in care.

Ukraine is a middle-income country of 45.5 million people that gained independence in 1991. Among the estimated 310,000 PWIDs in Ukraine, the prevalence of HIV and HCV is extraordinarily high and contributes to excess morbidity and mortality (Azbel et al., 2013; Mathers et al., 2010; Poznyak et al., 2002). To address HIV prevention and treatment needs, OAT with buprenorphine maintenance therapy (BMT) was introduced in 2004 (Bruce, Dvoryak, Sylla, & Altice, 2007; Lawrinson et al., 2008) with methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) added in 2008 (Schaub, Chtenguelov, Subata, Weiler, & Uchtenhagen, 2010).Despite evidence supporting OAT, <3% of PWIDs (∼8,000 PWIDs) in Ukraine (Degenhardt et al., 2014; Wolfe, Carrieri, & Shepard, 2010) are receiving OAT (UCDC, 2015). Of those on OAT, approximately 20% are female corresponding to the sex distribution of PWIDs surveyed in Ukraine (Balakireva, 2012; Corsi et al., 2014), and 40% are HIV-infected. On the other hand, incarceration in Ukraine is high (305 people imprisoned per 100,000 population, compared to a mean global incarceration rate of 144 per 100,000), excluding those detained by police or in pre-trial detention (Walmsley, 2014). Moreover, there is evidence in Ukraine that police harassment of PWIDs is common (Booth et al., 2013; Izenberg et al., 2013; Mimiaga et al., 2010).

Even with the many documented personal and societal benefits of OAT (Altice et al., 2011; Altice et al., 2010; Amato et al., 2005; L. Gowing et al., 2011; Mattick, Breen, Kimber, & Davoli, 2009; Newman & Whitehill, 1979; Strain, Stitzer, Liebson, & Bigelow, 1993) and its promising start in Ukraine, adequate OAT scale-up has encountered multiple individual, programmatic and structural challenges that have constrained OAT expansion (Bojko et al., 2015), thereby thwarting HIV prevention and treatment goals in Ukraine (Bojko et al., 2013; Bruce et al., 2007; Izenberg et al., 2013; Mimiaga et al., 2010; WHO, 2013).Under the assumption that drug policy should be informed based on scientific evidence affirming the benefits of OAT, the complexity of barriers and facilitators to OAT scale-up (Stevens & Ritter, 2013) and using an implementation science framework (Chaudoir, Dugan, & Barr, 2013),we conducted the largest qualitative study of PWIDs in Ukraine to systematically examine multi-level barriers to OAT entry and retention. The importance of incorporating drug users' perspectives into drug policy and addiction treatment planning has been recognized as one of the pillars of effective nationwide strategies (Gelpi-Acosta, 2014; Hellman, 2012; Lancaster, Santana, Madden, & Ritter, 2014; Montagne, 2002; Page & Singer, 2010; Raikhel & Garriott, 2013; Singer et al., 2001; Stevens & Ritter, 2013; Tutenges, Kolind, & Uhl, 2015). Consequently, the lived experiences of Ukrainian PWIDs toward OAT were examined to understand how criminal activity and involvement with police influenced treatment-seeking behaviors and experiences with OAT, within their addiction trajectories.

Methods

Study Procedures

From February to April 2013, 25 focus groups (FG) with 199 PWIDs in 5 cities (Donetsk, L'viv, Odesa, Mykolaiv, Kyiv) in Ukraine representing distinct geographical regions of the country where both PWIDs and HIV prevalence is high were conducted with opioid dependent PWIDs. Using stratified convenience sampling, local research assistants recruited PWIDs who were either currently on OAT, had previously been on OAT or who had never been on OAT, to better understand the barriers and facilitators to OAT entry and retention. All FG discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed and translated into English and back-translated to ensure proper interpretation (Brislin, 1970). Five FGs were conducted in each city with an average of 8 participants in each group (Table 1). The study protocol and FG guide were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Yale University (USA) and at the Ukrainian Institute for Public Health Policy (Ukraine).

Table 1. Focus Group Distribution by Type and City.

| Type of FG | Kyiv | Odesa | Mykolaiv | Donetsk | L'viv | Total FG participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ON OAT >1 year | 11 | 11 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 51 |

| ON OAT <1 year | 9 | --- | 8 | 5 | 9 | 31 |

| NEVER OAT | 11 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 41 |

| PREVIOUS OAT | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 33 |

| WOMEN only | 7 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 36 |

| MIXED | --- | 7 | --- | --- | --- | 7 |

| Total FG participants | 47 | 35 | 41 | 45 | 31 | 199 |

Data Analysis

Within grounded theory research strategies and based on a number of known barriers and facilitators to OAT from the international literature, a code book was developed using inductive, contextual and procedural principles to identify domains (Bulawa, 2014; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Lincoln, 1985; Mansourian, 2006; Strauss, 1998; Taylor, 1985). Four trained researchers coded the transcripts with each transcript coded independently by two of the researchers using MAXQDA software, a qualitative data analysis package designed for text and content analysis (VERBI Software – Consult – Sozialforschung GmbH, 1989-2014). Any discrepancies in coding were discussed by the researchers and codes were assigned based on consensus. Detailed description of the city selection, types of FGs, recruitment process, FG guide, and coding strategy are described in previous publication from the same study (Bojko et al., 2015).

The current analysis focuses specifically on the domains related to the PWIDs' experiences with police involvement and criminal activity utilizing the ‘law enforcement’ and ‘imprisonment’ codes. Specific attention is paid to the narratives of how arrest and imprisonment impact the addiction pathway of opioid dependent PWIDs in Ukraine, which often involves periods of intensive drug use, short-term abstinence during periods of imprisonment, with eventual relapse to drug use post-release. After presenting the general context of law enforcement, we discuss data separately for those who have had experiences with OAT (currently and previously on OAT) and those who had never received OAT. Experience of these groups are similar in many ways, however, for proper intervention planning it is also important to discuss these differences.

We used the term maintenance with opioid agonist treatment (OAT) to reflect evidence-based addiction treatment with methadone and/or buprenorphine, however, older terms like opioid substitution therapy (OST), substitution maintenance therapy (SMT), and substitution treatment (ST) were kept without changes in participants' narratives to preserve the accuracy of their words.

Results

The characteristics of the 199 PWIDs are described in Table 2. The median age was 38 years with two-thirds being men (N=132). The overwhelming majority (N=165, 85%) of participants had been arrested, most often for illegal drug activities.

Table 2. Demographics of Total Focus Group sample.

| Variable | Total N=199 | |

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 132 | 66 |

| Female | 67 | 34 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married/single | 51 | 26 |

| Married/live with partner | 90 | 45 |

| Separated/divorced | 42 | 21 |

| Education | ||

| Complete high school | 90 | 45 |

| Professional technical | 24 | 12 |

| Completed higher | 22 | 11 |

| Employment (official) | ||

| Yes | 39 | 20 |

| Total income | ||

| 0 to < 600 UAH* | 56 | 28 |

| 600 -1800 UAH | 104 | 52 |

| > 1800 UAH | 37 | 19 |

| Ever arrested | ||

| Yes | 165 | 83 |

| Median age | 38 years (22-59) | |

UAH: Ukrainian hryvnia (At time of study, exchange rate was 8 UAH = US$1)

How law enforcement shapes addiction trajectories in Ukraine

Police corruption and misconduct as one of the driving forces of addiction trajectories were frequently discussed by participants regardless of their experience with OAT. The leading discourse was related to police orientation towards achieving the ‘conviction plan’ and the convenience of pursuing people who use drugs, as described by a an OAT patient from L'viv:

Their [police's] attitude is all about their performance plan. We either put you in jail, and if you don't want to go to jail, you give us money. Right, only money. They set you up. They shove something [illegal drugs] into my pocket, they put stuff themselves. You don't need to have anything illegal in you…If you bear that label of being a drug addict. (Male, L'viv, on OAT < 1 year)

Police harassment and surveillance of drug dealers caused FG participants to feel they were being “monitored”. Police often know where to find drug users, including where drugs are sold and near OAT sites. Respondents suggested that police often do not arrest dealers themselves, but rather observe who comes to buy drugs and extort them to collect bribes. Ruslan (Mykolaiv, on OAT < 1 year) shared his short communication with a policeman on this topic: “They got me when I had drugs on me. I ask him, why don't you get those drug dealers? And this cop, he tells me: ‘Why? There's only one who sells but many of you who buy from him and I can get you all.’ That's what they are saying.”

Similarly, the widespread and legal practice of detaining arrested individuals for 72 hours for identity verification concerned participants because it exposed them to symptoms of withdrawal and police extracting confessions:

You see… even based on these documents he certifies my identity. The law here allows you to keep a person in custody for 72 hours for no reason. To find out facts about you… for no apparent reason. To establish your identity… As far as I know, the medication's effect lasts basically either 25 or 40 hours… (Male, L'viv, on OAT <1 year)

Such practices may be correlated with the standpoint that a male OAT patient from L'viv articulated: “Whereas in other countries there actually exists the presumption of innocence - we don't have it here, here you need to prove that you are not guilty or pay cash. It's not them who prove you're guilty, it's you who must prove your innocence.” In line with this is Andriy's (L'viv, previous on OAT) experience:

I ask him [police officer]: why do you put me in jail? Me… a sick person? They got into my place, broke the door, they found this shirka [homemade opioid made from poppy straw]. They tell me, essentially we put you in jail not because you inject, but we gotta put you there, Andriy… you're a drug user, you have to understand! You have to get 200-300 UAH [US$40 at the time of data collection] every day, you don't work, so that's for sure that you are stealing things. I tell them: okay, I steal, but you gotta get me when I do it.

Sasha, on the other hand, described financial motives behind the police's harassment of drug users:

Yeah, now it's about money. Look at the cars they [police] drive. Yeah. They don't take you to the police station, they go straight to your place. You have nothing at your place? No computer? Oh, there is a computer. Fine, let's go, I'll have a look at your computer. And we settle this question. They make money everywhere. And what I think is that they are not interested in people going to the OST program. It's better for them if we go and buy it from those pushers. (Mykolaiv, on OAT < 1 year)

Moreover, PWIDs voiced a perception that police control the drug market through selective enforcement of drug trafficking laws and engagement in drug trade as Slava (an OAT patient < 1 year) from Kyiv described: “Earlier, I would go and mow the natural stuff, cook it and sell it. There was such a market. I would pay policemen to avoid imprisonment, but now policemen sell their own drugs and protect their own market.”

Many PWIDs, whose lives involve a daily search for money to procure drugs with continuous attempts to evade the scrutiny by law enforcement, repeatedly faced police harassment that often resulted in their arrest. Those who had been arrested and imprisoned describe the very unpleasant experience of going through “cold turkey” detox since methadone and/or buprenorphine are generally not available in Ukrainian prisons. Within penitentiary system suffering from symptoms of withdrawal usually receives little medical intervention and is regarded by participants as being a ‘cruel’ approach to detoxification. According to Pavlo from L'viv, a previous OAT client, the method of treating the abstinence syndrome [withdrawal] in prison is to: “Give you one pill, cut into two pieces. This analgin [commonly used tablets from group of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with an analgesic effect], they tell you…that's for the withdrawals. And this one…for the stomach ache…don't mix them up (laughing).”

Interestingly, many mentioned prison as the most effective setting to abstain from drugs, even if for a short period. Upon release, many considered themselves to be drug-free, but according to the participants, relapse is universally inevitable after release:

I tried many things, but to be honest nothing really kept me off drugs apart from jail. But then immediately after being released, I returned to drug use again. (Denis, Mykolaiv, On OAT <1 year)

Participants describe how drug use, which results in a cycle of searching for money and drugs, is followed by arrest and incarceration. Vitalii from Kyiv (on OAT <1 year) summarized the outcome of supplying his personal drug addiction: “And for me to get the money is necessary to rob somebody. And why are people spending the time in prison? It's very simple – when you feel bad, you steal, and then you're caught and imprisoned. Everything is straight-forward.”

Many of the participants in each city outlined a similar cycle of drug use/incarceration/release/relapse (Figure1). Yurii (L'viv, on OAT >1 year) reiterated his repeated and unsuccessful struggle with abstaining from drug use in prison, being sober, and then relapsing after release:

There were even those attempts [to quit drugs] when I got into jail. So I got off drugs myself. No pills. No injections. I got off and I thought to myself – what a hero I am, I get out of jail and that's it. I won't inject. Then I got out and it started all over again.

Figure 1. Addiction trajectory.

Some PWIDs, however, are not abstinent while in prison as a male OAT participant from L'viv described:

MV: … I spent 6 years in prison, I was released 18 months ago. And I took such medications as Subutex [partial agonist/partial antagonist]. But they don't provide it here. It is available abroad only, yeah.

M: And where did you take it? Where you in a foreign country?

MV: In jail, of course. You can get anything in jail.

Law enforcement and police harassment: motivation for OAT entry and retention

Current and previous OAT patients describe how their perceptions of similar cycles led them to look at OAT as a change agent. Sasha (Donetsk, on OAT >1 year) shared his perspective on the debilitating problem of drug addiction and imprisonment and the decision to start OAT to “get on with life”:

“In a nutshell, by that moment, I had served 7 sentences, I was fed up with these jail rounds, with thefts, injections, I was sick of it all so bad that I wanted to get on with life. I came to the realization … life values changed. Lifestyle changed. The price changed… Well, I did not see any value in gold, in money, there was no value in it. And the drug was of no value for me. I almost stopped doing drugs. But! The body got so used to it that I had to shove something in there.”

Recognition of the cycle and the fear of imprisonment motivated some participants to search for treatment alternatives and to access OAT:

“And that's it. So I thought, what shall I do? Go there for the police to get me, and if they get me, I won't get a conditional discharge anymore. It's not possible… I've got four conditional discharges [a designation similar to probation when an individual is found guilty, no conviction is officially registered, but community supervision is required] already. How many more will they give me? They are going to put me in jail this time. So, I made this decision not to go back into it [jail]… I decided to go and get into this program [OAT].” (Ruslan, Mykolaiv, on OAT <1 year)

Almost unanimously participants on OAT admitted that leaving criminal activity was one of the key factors influencing their decision to start OAT. Oleg (Mykolaiv, on OAT<1 year) described his catalyst to start OAT and the changes that decision brought to his life:

“It's the main factor that brought me here – police. I don't want to go to jail, I don't need it. What for?… So it brought peace to my family, to my own life. That's how it is. Some kind of order.”

Participants talked intensely about the eventual unburdening effect of OAT, which returned a sense of freedom which Nazar (OAT patient > 1 year from L'viv) described as “I don't keep looking behind myself all the time.” Vika, a previous OAT client from Kyiv, reiterated this feeling of happiness and freedom since “I could watch the police patiently without noticing it and without fearing and looking. And I was happy because I could speak loudly and not whisper.”

Being on OAT allowed clients to experience the other side of the law. Yuliya from Kyiv noted: “You know that you come, take your medication [OAT] and nobody will take you down. Meaning, you are free and law-abiding, not off the law” while one of the long-term OAT clients from Donetsk stated that “It's been five years, life is going on and stuff. Oh Lord, knock on the wood, you leave it all, and parents will see that cops leave you alone.”

Another OAT patient from Donetsk mentioned that desire to protect family from his imprisonment, additionally, served as a facilitator for OAT entry: “The only reason why I chose the program was because of parents. Because, in the end, I was imprisoned three times because of drugs. And my parents, so to say, were ‘imprisoned’ with me.”

Law enforcement and police harassment: barriers and consequences to OAT entry and retention

While fear of law enforcement motivates some PWIDs to engage with OAT, police harassment may offset treatment experience and its effectiveness. OAT participants in all cities mentioned OAT sites as an easy access point for police to identify potential suspects. Sometimes this police harassment violated patient's basic rights to confidentiality of treatment. One such salient case was described by OAT participants from Mykolaiv:

Larisa: The fact is that there was a case of theft in our district, so they all came to the methadone site and started taking pictures of us for the victim to identify the criminal. They said we were all in a high-risk group as we all had a criminal past. So we had to let them make those pictures. The ones who refused were denied access to the [OAT] site. It was a weekend. But then our lawyer made a call to the prosecutor and they got lost the next moment.

Nina: Or they come and stand there waiting at the site if they need someone. It's such a convenient place for them if they are looking for somebody. Hey ho, they take away a person, without even asking any questions. I mean, at least let him first take his pills, and then go talk to him. And more than that, don't treat him like that, better just invite him to talk. But that's not how they do it, they just put you down on the floor and everything's okay.

Such police practices cause distress and disturbances for the clients as discussed by Dmitry and Sasha from Mykolaiv who started OAT <1 year ago:

Dmitry: When they [policemen] are there [at the OAT site], people start panicking. Everyone is thinking: “Maybe I'm the one they are looking for?” And start hiding [and don't come for treatment]…

Sasha: Even though you didn't do anything. It's just one of those cops you used to know… “Come here, Sasha!” And he starts telling me things… You explain him that you are getting your treatment, that's all. Let me alone. “No-o-o, you're the one we need”. And that's it, they don't let you go [take you away] …

Police, who previously focused on active drug users, are now situating themselves at OAT sites was perceived by OAT participants as means of ‘earning’ extra money easily because bribes are often required by police in exchange for not being detained. This newer strategy seems to have replaced or minimally altered how PWIDs fear police irrespective of whether they are doing anything illegal or not. Vitalik (L'viv, on OAT > 1 year) understands the situation the following way:

“Well, it turns out that police has much less… work, chances to earn money, that's it. There were drug addicts, whom they knew…here lives that one, and that one and that one…they could come from time to time and somehow [do] something. And now they're gone, everyone's on OST, and no one is running around. Everyone is being treated… somehow, [they] are taking care of themselves, in a word. And they go around angry. Looking for [something]…even here under the program they stand very often.”

Another opinion voiced by the participants was that harassing PWIDs on their way to treatment is within their general strategy to use OAT as a conspiracy tool to control drug users. This perception is one of the voiced drawbacks of the OAT program in Ukraine that impedes scale-up of the program in the eyes of OAT patients. Oleg (Mykolaiv, on OAT < 1 year) talked about his perception of the situation:

“Now they know it all, I mean they know whom they can find and where. Even if he [patient] doesn't show up for a day or two, he'll be there on day three anyway. So they made their work easier, let's say. That's why there is such an opinion that it is all done to [control and eventually] kill drug users. Get rid of them. That's how I see it at least [reasons for such opinion].”

Another potential problem for the OAT clients is the uncertainty regarding keeping their driving privileges once they register with narcology [Soviet term for addiction treatment] as a person with addiction. Officially, an OAT client is not prohibited from driving a car while being in treatment, however, police use this uncertainty to harass OAT patients for driving. Police take advantage of the fact that for many OAT patients, driving is a means to earn a living or transportation to employment. A male participant from L'viv, on OAT <1 year described his story with his driver's license and the police:

“As for the driving license, I've had a situation so many times… I have a certificate. I have a contact to call and ask them to interfere and calm the police down…that the chiefs are your friends, so that the police leave you alone. Roughly speaking, no other way is possible. And for a Petya Chmo [generic name for somebody extremely stupid or irritating, or ridiculous] with no influential friends the price is 3,000 UAH [US$ 375 at time of data collection] if you want your driving license preserved. 3,000 UAH there right on the spot, if you don't have that money on you, that's it, your license will be withdrawn and your car, confiscated.”

OAT participants expressed fear that treatment would be interrupted if they were detained by police. Although there are “legal” mechanisms by which OAT may be made available in pre-trial detention centers, this practice largely relies on regional initiatives and political will. Participants often are also forced to snitch on other PWIDs to avoid experiencing the abstinence syndrome [withdrawal symptoms]. Changes occur at a very slow pace and often have to be ‘stimulated’ by the patients:

Yuri: … For example, I've got this dose of 190 mg [of methadone]. So, if I get into a pre-trial detention center, they tell me right away: either you pay money and we take you to the site or you give us information. So you gotta narc someone out. Make something up…

Nazar: Yeah, policemen take advantage of us.

Yuri: Yeah, he takes advantage [of me] as he knows that I need it [methadone]. (L'viv, on OAT >1 year)

Furthermore, the absence of drug treatment in prisons leaves OAT patients very limited options to deal with their addiction, as described by long-term OAT participants from L'viv:

Yurii: It's just if they take someone into jail, for example. He's got a pretty high dose, you know… so he feels bad [from withdrawal symptoms]. Really bad. Their drug treatment doctor comes, looks at him – raise your hand, raise your leg. And that's all – the critical point is behind. I mean, he's got through the critical point [of the abstinence syndrome]. Now he won't die, right? Now it's on the down-grade. They only took him here for two days, right from the pre-trial detention center. Then he goes to jail, so how, how could he pass this critical point? Oleg (suggesting): This point did not occur yet.

Throughout Ukraine, OAT must be supervised on a daily basis and with no “take home” doses permitted, even in the event of hospitalization or incarceration. Allowing OAT prescriptions to be filled in pharmacies or in primary care clinics would potentially improve retention by allowing individuals to avoid daily harassment and risk of arrest. OAT (only buprenorphine) made available in rare cases by prescription in rare cases is relatively new and uncommonly available due to regional discretion and agreements. One previous OAT participant from Mykolaiv explained: “for them [police] it is easier to prohibit than to allow”, demonstrating that police is not willing to put efforts into helping institutionalize OAT by prescription within oblasts because they can't find you. Participants are aware of the importance of the police in the process of ‘allowing’ OAT by prescription in the region and demonstrate their understanding of how police attitudes could be changed:

Andrey: Policemen are the first to object to giving us those pills to take home. But they understand this buprenorphine in such a way that buprenorphine leads to the growth of those organizations [The Association of Substitution Treatment Advocates of Ukraine]. As in those regions [where advocacy is effective] there was a [newly intiated] prescription system for Adnok (brand name for buprenorphine). As our police thinks we can sell those pills… So I keep telling [everyone] that the first thing we need to do is not to change their opinion [about buprenorphine], but to change their opinion about us. What I mean is that we want at last to become productive members of the society, we want to become ordinary people in this world, so that they don't think that if we used to be drugs users, we still are… (L'viv, on OAT >1 year)

Perception of control as a barrier to initiating OAT

For those never on OAT perception of being under the control of something or someone, be it police or a daily supervised treatment program, served as substantial barrier for initiating OAT. Sergey (Donetsk, never on OAT) stated: “Last time when I got out of jail I also wanted to enter this OST program, but then I thought… for me that's a total control, I don't want EVERYBODY controlling me.”

Another source of control and power that served as a strong barrier to initiating OAT was police observation. A male participant from Odesa (never on OAT) described it as follows: “I try to explain to you, to make you understand that everybody wants to let anybody know about the program. That is all, and it is not a problem, you can go and follow that program. But not everyone will go there, because the authorities will know about you and no one wants it. That is all.”

As police make frequent visits to the OAT sites clients know that police can have access to narcological registries. For example Andrey (L'viv, never on OAT) voiced his concern about the required registration to receive publicly funded OAT services: “Why do I say this about registration, I mean in general, I am almost sure that police has access to it.”

Discussion

Though reports of mutual fear between PWIDs and police have previously been described in Ukraine (Mimiaga et al., 2010), to our knowledge, this is the first and the largest account of PWID's ‘voices’ of police practices specifically related to OAT programs in Ukraine. Moreover, it is the first qualitative exploration of life addiction trajectories of PWIDs in Ukraine, which appear indelibly shaped by law enforcement policies and practices. For this analysis we have included a range of participants to better understand the diversity in the ‘law enforcement’ and ‘imprisonment’ narratives of those who are actively using drugs and those who have experience with OAT. We found discussions similar across focus group type although as expected, those currently on OAT and previously on OAT discussed police interference with OAT treatment more frequently. Consequently, the topic of law enforcement and imprisonment occurred in two different contexts: general police practices towards PWIDs and police practices specific to the OAT sites' operation. Our analysis did not aim to identify frequency of law enforcement and imprisonment discussions by location, however, participants' narratives indicate the importance of regional context and local point of leverage, which should be explored in future analyses.

Voiced addiction trajectories in the lives of PWIDs can be summarized as a cycle consisting of a daily search for money and drugs under constant harassment of police, arrest and experiencing forced detox and abstinence symptoms while detained. This paradoxical ability to describe this cycle of addiction with incarceration and a lack of recognition that “being in a controlled setting” like prison, jail or even in a voluntary drug treatment program where they undergo supervised withdrawal from opioids, is consistent with the new qualifier to the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual definition of having an opioid use disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Future framing of having an opioid use disorder in this manner will be crucial for expanding OAT in community settings, but also to motivate PWIDs to either continue (Rich et al., 2015) or initiate it during periods of confinement (Dolan et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 2014; Kinlock et al., 2009; Larney, Toson, Burns, & Dolan, 2012; Macalino et al., 2004) in order to optimize health post-release, whether to reduce overdose (Hedrich et al., 2012; Kinner et al., 2012) or improve HIV treatment outcomes (Springer et al., 2010; Springer et al., 2012)

Stigma, and even frank discrimination toward PWIDs, is strong in Ukraine and figures prominently into how police view and treat them. For example, in the view of PWIDs themselves, there does not appear to be a difference in how police treat them based on whether they are in treatment or not (Zajonc, 1980) The proverbial “once a drug user, always a drug user” comes to mind. Some examples of this perception include exclusion from driving or certain kinds of employment once someone officially “registers” as a drug users – a requirement for OAT entry, continued harassment of individuals at OAT sites, requirements for daily supervision that continue to put PWIDs in treatment in harm's way with the police, and continued push-back by police to disallow expansion of OAT to primary care or pharmacy settings. Specifically, once a PWID becomes officially “registered” as a drug user, a national requirement to receive OAT, the police keep them under constant surveillance and even if the person is not using drugs or committing petty crimes, police still demand bribes. Police recognize that PWIDs are vulnerable, and they can arrest and detain them for 72 hours without officially charging them, recognizing that PWIDs will experience severe symptoms of withdrawal during this time, as a threat in order to make them pay. This is especially concerning for OAT clients who cannot access their daily medications from their treatment providers, which forces them to experience symptomatic opioid withdrawal while awaiting adjudication (Izenberg et al., 2013). These results confirm previous findings showing existent disharmony between medical and political domains of addiction leading to the simultaneous co-existence of coercive criminalizing institutions and effective addiction treatment (Raikhel & Garriott, 2013). Earlier Lovell (2013) has shown that PWIDs in Ukraine themselves feel more like criminals than patients and, sadly, based on our data this perception has not changed even with therapeutic technologies that are currently available for effectively treating opioid addiction.

Societal stress also cause many PWIDs who are released from incarceration to relapse to drug use, which then results in a cycle of searching for money and drugs, followed by re-arrest and re-incarceration. The chronic nature of addiction results in this cycle being perpetuated multiple times until viable treatment alternatives or death occurs. Similar cycles have been described in many settings (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009; Hellman, 2012; Raikhel & Garriott, 2013; Singer et al., 2001), therefore, it is important to identify effective approaches used elsewhere to break these patterns.

Recognition of this cycle, sadly after many incarcerations that negatively impacted the individual and the family, eventually brought many participants to the OAT program, yet several barriers prevented them from starting treatment. These barriers include negative perceptions about the program, not wanting to be ‘chained’ to their treatment or controlled and, paradoxically, being under constant police ‘surveillance’. For these reasons, actual law enforcement and police practices, combined with PWIDs' perception of these activities as pervasive ‘control’ impact OAT uptake in several ways. Specifically, police harassment, fear of imprisonment and the dynamic drug market play an important role in the decision to initiate OAT. Complexity of these interactions demonstrates the intricate interplay between different institutions and stakeholders in the field of drug policy and practice (Stevens & Ritter, 2013) and calls for system-level approaches for making changes (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009).

Our data indicate several potential approaches for interventions. At the individual level, for PWIDs who have not yet faced the criminal justice system, peer-driven interventions that promote risk reduction, entry into OAT and healthcare services, have been shown to be effective and viable approaches to prevent negative consequences of drug use (Broadhead et al., 2002; Broadhead et al., 1998). Peer driven interventions may be implemented for OAT initiation and retention as they may result in sustained behavior change. For example, community representatives who have been successful with OAT may provide support for those who face challenges in accessing medical services, encouraging them to pursue drug treatment, and reinforcing the need to be retained in care. The influence of peers can thus change group norms and promote positive behavioral change while structural changes may take time (Abdul-Quader et al., 2006; Bandura, 1977; Heckathorn, 1990).

For those PWIDs already involved with the criminal justice system, such interactions may be an effective point of entry to break the addiction trajectory cycle by initiating PWIDs on OAT within prison and ensuring effective transition post-release (Kinlock et al., 2009; Springer et al., 2010; Springer et al., 2012). In order for this linkage to be effective it is important to overcome existent personal, programmatic and structural barriers for OAT entry and retention, which appear to be challenging with criminal justice personnel in Ukraine (Polonsky et al., 2015).

Structural changes will require alternative strategies. First, there is a considerable need to change the image of OAT programs for both clients and society by introducing effective social marketing campaigns in Ukraine. Second, alternative OAT scale-up strategies, which have been effective elsewhere, that more broadly allow OAT by prescription by primary care physicians and dispensed by pharmacies has not only been effective, but associated with reduced overdose (Bachireddy, Weisberg, & Altice, 2015). For those who have demonstrated stability on OAT, allowing “take-home” dosing or making OAT available by prescription combined with re-directing ‘anti-diversion’ police efforts towards breaking the supply chain by targeting drug dealers rather than PWIDs can also be effective (Sabet, 2014; UNODC, 2014). Third, there is evidence police education about addiction as a medically treatable condition and including them as a coordinated effort not only to engage them in treatment and harm reduction services is a crucial component to tacking both the drug addiction problem, but also to reduce HIV transmission (Beyrer, 2012; Jardine, Crofts, Monaghan, & Morrow, 2012; Thomson, Leang, et al., 2012; Thomson, Moore, & Crofts, 2012). Fourth, a multi-pronged approach to introducing and expanding OAT to tackling the drug problem, especially with OAT scale-up, must include the community and criminal justice system, from criminal sanctions, policing practices, adjudication from drug courts and detention in pre-trial detention centers and in prisons. Such settings should not differentiate making OAT available and ensuring effective treatment throughout all of these transitions. Experiences from several western European countries document that this can effectively be accomplished, including transition back to the community (Hedrich et al., 2012; MacArthur et al., 2014). Partnership between police and public health is a crucial component for these interventions to be effective, as has been demonstrated in many settings worldwide (Beletsky et al., 2012; DeBeck et al., 2008; Sharma & Chatterjee, 2012) and as suggested by our local data. One of the feasible approaches in changing law enforcement's agenda with PWIDs is through incorporating narratives about drug injection as a public health emergency rather than a criminal justice problem with validity of OAT as an effective tool to tackle this emergency (Stevens & Ritter, 2013). Examples of interventions with the police to facilitate harm reduction strategies have been successful, but often require continued education and monitoring (Davis, Burris, Kraut-Becher, Lynch, & Metzger, 2005; Jardine et al., 2012; Sharma & Chatterjee, 2012; Thomson, Leang, et al., 2012; Thomson, Moore, et al., 2012).

Unfortunately, during the last decade, little has changed in police practices and approaches towards PWIDs in Ukraine (Booth et al., 2013; Lovell et al., 2013): police continue to plant drugs, demand bribes, coerce PWIDs to ‘cooperate’, and detain them for up to 72 hours with no solid evidence. There are at least two explanations for such practices that stemmed from our data. First, there is the assumption that there are a targeted number of convictions that have to be met by police without exception, which may be a distant consequence of the ‘war on drugs’(Jardine et al., 2012). On the way to meeting this ‘plan’ police often take the easiest route by harassing drug users whose contacts they have access to, presumably through registration, or by ‘pasturing’ near OAT sites and waiting for someone to match a suspect's description or by coercion to frame someone for a crime. Police influence OAT site operations not only through surveillance but also by impacting implementation of OAT prescriptions, continuity of OAT in pre-trial detention centers, and leveraging power to take OAT patient's driver license. All these ‘windows of opportunity’ serve as police power and influence over the lives of OAT patients. Whenever law enforcement exhibits such power differentials, OAT patients suffer from suboptimal access to effective treatment and care. OAT patients, nevertheless, admit that interfacing with police becomes less stressful than when they were actively using drugs because of certainty that they are not engaging in illegal activities.

The second explanation is at the core of many societal problems in Ukraine – corruption fueled by appetite for money and the garnering of resources or favors from those that police have power over. The topic of corruption is far beyond the scope of this paper, yet, we cannot ignore the outstanding repercussions that go with the ‘broken’ police system (Singer, 2006a). Ukraine, especially during last two years in the setting of political instability, has stricken the world with the image of corrupt police, violent internal forces and selective law enforcement (Arkin, 2011; Beck & Chistyakova, 2004; Fijnaut & Huberts, 2002). While Ukrainian society superficially commented that it will not tolerate the ‘old’ corrupt system, such changes are not made swiftly. Changing the legal environment from criminalization-focused sanctions towards a public health orientation is a necessary structural change if Ukraine wants to effectively intervene on the volatile epidemics that accelerate morbidity and mortality from addiction, HIV, HCV and tuberculosis. Central to these changes is re-shaping the context for addiction trajectories that favor treatment over criminalization (Hahn et al., 2002; Judd et al., 2005; G. J. MacArthur et al., 2012; Maher et al., 2006; Raikhel & Garriott, 2013; Strathdee, Beletsky, & Kerr, 2015). While structural changes may be slow, many police practices stem from societal attitudes and beliefs around drug use and people who use drugs, and as such, are susceptible to change through ad hoc interventions, especially at the regional level (Bojko et al., 2013; Degenhardt et al., 2010; Polonsky et al., 2015; Wolfe et al., 2010). There are several opportunities for effective interventions that include changing police beliefs and norms (Beletsky et al., 2011; Beletsky, Thomas, Shumskaya, Artamonova, & Smelyanskaya, 2013; Beletsky et al., 2012; Compton et al., 2014), implementing transitional care (Azbel et al., 2013, 2014; Kinlock et al., 2009; Morozova et al., 2013; Wickersham, Marcus, Kamarulzaman, Zahari, & Altice, 2013; Wickersham, Zahari, Azar, Kamarulzaman, & Altice, 2013), engaging law enforcement by empowering and encouraging police to facilitate “referral” for OAT and harm reduction services (Beletsky et al., 2012; DeBeck et al., 2008) that can have a ‘bottom-up’ effect to facilitate change rather than waiting for authoritative choices at the highest official levels (Stevens & Ritter, 2013).

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations that exist for other qualitative research. The recruited sample cannot be considered fully representative of PWIDs. Nonetheless, the large sample size and recruitment from the highest burden settings within Ukraine provide important insights for the Ukrainian context, but does not allow generalization to all countries or settings. The nature of the recruitment process may have caused self-selection bias, with those most comfortable with focus group settings and the research process agreeing to participate. Focus group methodology itself may have introduced barriers related to disclosure, since complete anonymity and confidentiality is hard to guarantee during focus groups. This factor may have especially influenced the narratives regarding such sensitive topics as imprisonment history and interaction with police. Our participants, however, were not asked to reveal their identity and use of pseudonyms were encouraged during the FGs, and they appeared candid regarding their time spent in prison and the police practices they have encountered.

Our sample consisted of participants from urban areas in Ukraine; therefore, our results may not fully describe experience of those in rural areas, where police punitive practice may be at a different level than in larger cities. Although we recognize that police practices are ingrained in macro-societal level, we have described their impact on PWIDs life trajectories and OAT implementation to the extent it has been perceived by our participants. Although some perceptions may appear exaggerated, we clarify that findings presented here reflect the ‘voices’ of drug users, the ones who must ultimately decide on whether to access treatment or not, and provides important contextual insights into their lived experiences and impressions.

Conclusions

This discursive account of PWIDs experiences with law enforcement and imprisonment in Ukraine calls for structural and regional level changes in law enforcement policies and practices towards PWIDs and OAT that would take a more public health and human rights approach as opposed to the current punitive and vindictive approach toward PWIDs. These changes should include structural shift as well as short-term interventions aimed to decrease police harassment of PWIDs and interference with OAT programs, increased law enforcement of drug trade, creation of a positive OAT image and shifting of the police's stigmatizing perceptions of PWIDs and addiction. A culturally relevant survey based on this qualitative data has been implemented with over 1500 PWIDs in the same geographic regions of Ukraine in order to quantify the barriers to entry and retention in OAT associated with the police practices and law enforcement attitudes and beliefs voiced during the FG discussions. It is anticipated that the mixed methods data will be instrumental in designing interventions and updating policies and procedures. Cooperation between public sector and criminal justice system will be a necessary precursor for the implementation of any effective interventions or policy change.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Institute on Drug Abuse for funding for research (R01 DA029910 and R01 DA033679) and career development (K24 DA017072) as well as the Global Health Equity Scholars Program funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Research Training Grant R25 TW009338).

We would also like to extend our gratitude to our local research assistants and all the focus group participants in each city for their dedication and time

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to report

References

- Abdul-Quader AS, Heckathorn DD, McKnight C, Bramson H, Nemeth C, Sabin K, et al. Des Jarlais DC. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling for recruiting drug users in New York City: findings from a pilot study. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):459–476. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alistar SS, Owens DK, Brandeau ML. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of expanding harm reduction and antiretroviral therapy in a mixed HIV epidemic: a modeling analysis for Ukraine. PLoS Med. 2011;8(3):e1000423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Bruce RD, Lucas GM, Lum PJ, Korthuis PT, Flanigan TP, et al. Collaborative B. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: results from a multisite study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(Suppl 1):S22–32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318209751e. [doi] 00126334-201103011-00005 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):367–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Sullivan LE, Smith-Rohrberg D, Basu S, Stancliff S, Eldred L. The potential role of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence in HIV-infected individuals and in HIV infection prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43 Suppl 4:S178–183. doi: 10.1086/508181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato L, Davoli M, Perucci CA, Ferri M, Faggiano F, Mattick RP. An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(4):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arkin E. Ukraine: HIV policy advances overshadowed by police crackdown on drug therapy clinics. HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2011;15(2):24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Grishaev Y, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Burden of Infectious Diseases, Substance Use Disorders, and Mental Illness among Ukrainian Prisoners Transitioning to the Community. PLoS One. 2013;8(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Grishaev Y, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Correlates of HIV infection and being unaware of HIV status among soon-to-be-released Ukrainian prisoners. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19005. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachireddy, Soule MC, Izenberg JM, Dvoryak S, Dumchev K, Altice FL. Integration of health services improves multiple healthcare outcomes among HIV-infected people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachireddy, Weisberg DF, Altice FL. Balancing Access and Safety in Prescribing Opioid Agonist Therapy to Prevent HIV Transmission. 2015 doi: 10.1111/add.13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakireva OB, Sereda T, Sazonova Ya Yu. Behavior monitoring and HIV Prevalence among Injecting Drug Users as a Component of Second Generation Sentinell Surveillance. 2012 Retrieved from Kyiv: http://www.aidsalliance.org.ua/ru/library/our/2012/me/idu_en_2011.pdf.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Chistyakova Y. Closing the Gap between the Police and the Public in Post-Soviet Ukraine: A Bridge Too Far? Police Practice and Research. 2004;5(1):43–65. doi: 10.1080/1561426042000191323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, Agrawal A, Moreau B, Kumar P, Weiss-Laxer N, Heimer R. Police training to align law enforcement and HIV prevention: Preliminary evidence from the field. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2012–2015. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, Thomas R, Shumskaya N, Artamonova I, Smelyanskaya M. Police education as a component of national HIV response: Lessons from Kyrgyzstan. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132, Supplement 1(0):S48–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.027. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, Thomas R, Smelyanskaya M, Artamonova I, Shumskaya N, Dooronbekova A, et al. Tolson R. Policy reform to shift the health and human rights environment for vulnerable groups: the case of Kyrgyzstan's Instruction 417. Health and human rights. 2012;14(2):34–48. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84887134565&partnerID=40&md5=40ad682f7b698db299fe0f68be1f8404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berleva G, Dumchev K, Kasianchuk M, Nikolko M, Saliuk T, Shvab I, Y O. Estimation of the Size of Populations Most-at-Risk for HIV Infection in Ukraine as of 2012. 2012 Retrieved from Kyiv: http://www.aidsalliance.org.ua/ru/library/our/2013/SE_2012_Eng.pdf.

- Beyrer C. Afterword: Police, policing, and HIV: new partnerships and paradigms. Harm Reduct J. 2012;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, Kral AH, Erringer EA, Kahn JG. Collateral damage in the war on drugs: HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 1999;10(1):25–38. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(98)00076-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bojko MJ, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. At the crossroads: HIV prevention and treatment for people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Addiction. 2013;108(10):1697–1699. doi: 10.1111/add.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojko MJ, Mazhnaya A, Makarenko I, Marcus R, Dvoriak S, Islam Z, Altice FL. “Bureaucracy & Beliefs”: Assessing the barriers to accessing opioid substitution therapy by people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2015;22(3):255–262. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2015.1016397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Dvoryak S, Sung-Joon M, Brewster JT, Wendt WW, Corsi KF, et al. Strathdee SA. Law enforcement practices associated with HIV infection among injection drug users in Odessa, Ukraine. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2604–2614. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois PI, Schonberg J. Righteous dopefiend. Vol. 21. Univ of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J Cross-Cultural Psych. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Altice FL, van Hulst Y, Carbone M, Friedland GH, et al. Selwyn PA. Increasing drug users' adherence to HIV treatment: results of a peer-driven intervention feasibility study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(2):235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00167-8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12144138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Weakliem DL, Anthony DL, Madray H, Mills RJ, Hughes J. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Rep. 1998;113 Suppl 1:42–57. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9722809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce RD, Dvoryak S, Sylla L, Altice FL. HIV treatment access and scale-up for delivery of opiate substitution therapy with buprenorphine for IDUs in Ukraine--programme description and policy implications. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(4):326–328. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulawa P. Adapting Grounded Theory in Qualitative Research: Reflections from Personal Experience. International Research in Education. 2014;2(1):145–168. doi: 10.5296/ire.v2i1.4921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns L. World Drug Report 2013 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33(2):216–216. doi: 10.1111/Dar.12110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Late for the epidemic: HIV/AIDS in Eastern Europe. Science. 2010a;329(5988):160, 162, 164. doi: 10.1126/science.329.5988.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Law enforcement and drug treatment: a culture clash. Science. 2010b Jul 9;:169. doi: 10.1126/science.329.5988.169. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20616266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Team HS. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Bakeman R, Broussard B, Hankerson-Dyson D, Husbands L, Krishan S, et al. Watson AC. The police-based crisis intervention team (CIT) model: II. Effects on level of force and resolution, referral, and arrest. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(4):523–529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi KF, Dvoryak S, Garver-Apgar C, Davis JM, Brewster JT, Lisovska O, Booth RE. Gender differences between predictors of HIV status among PWID in Ukraine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138(0):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.012. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Burris S, Kraut-Becher J, Lynch KG, Metzger D. Effects of an intensive street-level police intervention on syringe exchange program use in Philadelphia, PA. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):233–236. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall M, Montaner J, Kerr T. Police and public health partnerships: Evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver's supervised injection facility. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2008;3(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-11. Retrieved from http://www.substanceabusepolicy.com/content/3/1/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt, Mathers B, Vickerman P, Rhodes T, Latkin C, Hickman M. Prevention of HIV infection for people who inject drugs: why individual, structural, and combination approaches are needed. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):285–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt, Mathers BM, Wirtz AL, Wolfe D, Kamarulzaman A, Carrieri MP, et al. Beyrer C. What has been achieved in HIV prevention, treatment and care for people who inject drugs, 2010-2012? A review of the six highest burden countries. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan KA, Shearer J, White B, Zhou J, Kaldor J, Wodak AD. Four-year follow-up of imprisoned male heroin users and methadone treatment: mortality, re-incarceration and hepatitis C infection. Addiction. 2005;100(6):820–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Partners in Prevention, H. S. V. H. I. V. T. S. T. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker E. Population impact of mass incarceration under New York's Rockefeller drug laws: an analysis of years of life lost. J Urban Health. 2002;79(3):434–435. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.3.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):956–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijnaut C, Huberts LW. Corruption, integrity and law enforcement. Kluwer law international; Dordrecht: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Filippovych S. Impact of armed conflicts and warfare on opioid substitution treatment in Ukraine: responding to emergency needs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelpi-Acosta C. Challenging biopower: “Liquid cuffs” and the “Junkie” habitus. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2014;22(3):248–254. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2014.987219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A, Herrera J. Heroin addicts and methadone treatment in Albuquerque: a 22-year follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;40(2):139–150. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O'Grady KE, Vocci FJ. A randomized controlled trial of prison-initiated buprenorphine: prison outcomes and community treatment entry. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing L, Farrell MF, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali R. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD004145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004145.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing LR, Hickman M, Degenhardt L. Mitigating the risk of HIV infection with opioid substitution treatment. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(2):148–149. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Lovinger K. 30-year trajectories of heroin and other drug use among men and women sampled from methadone treatment in California. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118(2-3):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Lum PJ, Bourgois P, Stein E, Evans JL, et al. Moss AR. Hepatitis C virus seroconversion among young injection drug users: Relationships and risks. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;186(11):1558–1564. doi: 10.1086/345554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig T. Randomized controlled trial proves effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment in prison. Can HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2003;8(3):48. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15108656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Collective Sanctions and Compliance Norms: A Formal Theory of Group-Mediated Social Control. American Sociological Review. 1990;55(3):366–384. doi: 10.2307/2095762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich D, Alves P, Farrell M, Stover H, Moller L, Mayet S. The effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment in prison settings: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(3):501–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman M. Mind the Gap! Failure in Understanding Key Dimensions of a Drug User's Life. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(13-14):1651–1657. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.705693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Anglin MD, McGlothlin W. Sex differences in addict careers. 1. Initiation of use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13(1-2):33–57. doi: 10.3109/00952998709001499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izenberg JM, Bachireddy C, Soule M, Kiriazova T, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. High rates of police detention among recently released HIV-infected prisoners in Ukraine: Implications for health outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izenberg JM, Bachireddy C, Wickersham JA, Soule M, Kiriazova T, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. Within-prison drug injection among HIV-infected Ukrainian prisoners: prevalence and correlates of an extremely high-risk behaviour. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(5):845–852. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine M, Crofts N, Monaghan G, Morrow M. Harm reduction and law enforcement in Vietnam: influences on street policing. Harm Reduct J. 2012;9(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-9-27. Retrieved from http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/9/1/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd A, Hickman M, Jones S, McDonald T, Parry JV, Stimson GV, Hall AJ. Incidence of hepatitis C virus and HIV among new injecting drug users in London: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2005;330(7481):24–25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38286.8412277C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazatchkine M. Russia's ban on methadone for drug users in Crimea will worsen the HIV/AIDS epidemic and risk public health. BMJ. 2014;348:g3118. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O'Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months postrelease. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(3):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinner SA, Milloy M, Wood E, Qi J, Zhang R, Kerr T. Incidence and risk factors for non-fatal overdose among a cohort of recently incarcerated illicit drug users. Addict Behav. 2012;37(6):691–696. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster K, Santana L, Madden A, Ritter A. Stigma and subjectivities: Examining the textured relationship between lived experience and opinions about drug policy among people who inject drugs. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2014;22(3):224–231. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2014.970516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larney S, Toson B, Burns L, Dolan K. Effect of prison-based opioid substitution treatment and post-release retention in treatment on risk of re-incarceration. Addiction. 2012;107(2):372–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrinson P, Ali R, Buavirat A, Chiamwongpaet S, Dvoryak S, Habrat B, et al. Zhao C. Key findings from the WHO collaborative study on substitution therapy for opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS. Addiction. 2008;103(9):1484–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell A, Raikhel E, Garriott W. Elusive travelers: Russian narcology, transnational toxicomanias, and the great French ecological experiment. Addiction Trajectories. 2013:126–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Chaudhry A, Hsu J, Woodson T, Lau B, Olsen Y, et al. Moore RD. Clinic-based treatment of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients versus referral to an opioid treatment program: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):704–711. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macalino GE, Vlahov D, Sanford-Colby S, Patel S, Sabin K, Salas C, Rich JD. Prevalence and Incidence of HIV, Hepatitis B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus Infections Among Males in Rhode Island Prisons. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1218–1223. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1218. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1448424/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur, van Velzen E, Palmateer N, Kimber J, Pharris A, Hope V, et al. Hutchinson SJ. Interventions to prevent HIV and Hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: a review of reviews to assess evidence of effectiveness. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):34–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur GJ, Minozzi S, Martin N, Vickerman P, Deren S, Bruneau J, et al. Hickman M. Opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddux JF, Desmond DP. Ten-year follow-up after admission to methadone maintenance. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1992;18(3):289–303. doi: 10.3109/00952999209026068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, Jalaludin B, Chant KG, Jayasuriya R, Sladden T, Kaldor JM, Sargent PL. Incidence and risk factors for hepatitis C seroconversion in injecting drug users in Australia. Addiction. 2006;101(10):1499–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansourian Y. Adoption of grounded theory in LIS research. New Library World. 2006;107(9/10):386–402. doi: 10.1108/03074800610702589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maru DSR, Basu S, Altice FL. HIV control efforts should directly address incarceration. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2007;7(9):568–569. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70190-1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Mattick RP, et al. Injecting Drug U. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):1014–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, O'Brien CP, Druley P, Navaline H, et al. Abrutyn E. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6(9):1049–1056. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8340896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Dvoryak S, Reisner SL, Needle R, Woody G. “We fear the police, and the police fear us”: structural and individual barriers and facilitators to HIV medication adherence among injection drug users in Kiev, Ukraine. AIDS Care. 2010;22(11):1305–1313. doi: 10.1080/09540121003758515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagne M. Appreciating the user's perspective: Listening to the “methadonians”. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37(4):565–570. doi: 10.1081/ja-120002814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS. Treatment as prevention: toward an AIDS-free generation. Top Antivir Med. 2013;21(3):110–114. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23981598. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS, Lima VD, Harrigan PR, Lourenco L, Yip B, Nosyk B, et al. Kendall P. Expansion of HAART coverage is associated with sustained decreases in HIV/AIDS morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission: the “HIV Treatment as Prevention” experience in a Canadian setting. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova O, Azbel L, Grishaev Y, Dvoryak S, Wickersham JA, Altice FL. Ukrainian prisoners and community reentry challenges: implications for transitional care. International journal of prisoner health. 2013;9(1):5–19. doi: 10.1108/17449201311310760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman RG, Whitehill WB. Double-blind comparison of methadone and placebo maintenance treatments of narcotic addicts in Hong Kong. Lancet. 1979;2(8141):485–488. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91550-2. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/90214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell JA. A Follow-Up of Narcotic Addicts; Mortality, Relapse and Abstinence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1964;34:948–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1964.tb02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page JB, Singer M. Comprehending drug use: Ethnographic research at the social margins. Rutgers University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Joy R, Kerr T, Wood E, Press N, et al. Montaner JS. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: the role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky M, Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Taxman FS, Grishaev E, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Challenges to implementing opioid substitution therapy in Ukrainian prisons: Personnel attitudes toward addiction, treatment, and people with HIV/AIDS. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148(0):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.008. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznyak VB, Pelipas VE, Vievski AN, Miroshnichenko L. Illicit drug use and its health consequences in Belarus, Russian Federation and Ukraine: impact of transition. Eur Addict Res. 2002;8(4):184–189. doi: 10.1159/000066138. doi:66138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikhel EA, Garriott WC. Addiction trajectories. Durham and London: Duke University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13(2):85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, McKenzie M, Larney S, Wong JB, Tran L, Clarke J, et al. Zaller N. Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350–359. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62338-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]