Abstract

Novel methanocarba adenosine analogues, having the pseudo-ribose northern (N) conformation preferred at adenosine receptors (ARs), were synthesized and tested in binding assays. The 5′-uronamide modification preserved [N6-(3-iodobenzyl)] or enhanced (N6-methyl) affinity at A3ARs, while the 2′-deoxy modification reduced affinity and efficacy in a functional assay.

There are four subtypes of adenosine receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3), all of which are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Modulation of adenosine receptors by selective agonists and antagonists1,2 has the potential for the treatment of a wide range of diseases, including those of the cardiovascular, inflammatory, and central nervous systems. For example, selective A1 and A3 receptor agonists protect cardiac myocytes from the damaging effects of ischemia.3 Such agonists have also been shown to be protective in models of cerebral ischemia.4 In general, adenosine acts as a protective local mediator, which responds to stress applied to a system as a negative feedback control, leading to either increased energy supply (usually via the A2A receptor) to the organ or diminished energy demand (usually via the A1 receptor). Recently, A2A receptor agonists have been proposed as antiinflammatory agents and for use in ischemia reperfusion.5

Numerous structure–activity studies of adenosine derivatives as receptor agonists2,6 conclude that selectivity may be provided by specific substitutions of the adenine ring. For example, N6-cycloalkyl groups favor selectivity for A1 versus A2A/A3 subtypes, and N6-benzyl substitutions favor selectivity for A3 versus A1/A2A subtypes. Selectivity for the A2A receptor is often achieved through substitution at the 2-position. There are currently no selective agonists of the A2B receptor. Modifications of the ribose moiety of adenosine agonists are less well tolerated and therefore less amenable to extensive modifications. However, small alkyl 5′-uronamide modification of the ribose often enhances affinity of adenosine derivatives at multiple subtypes.

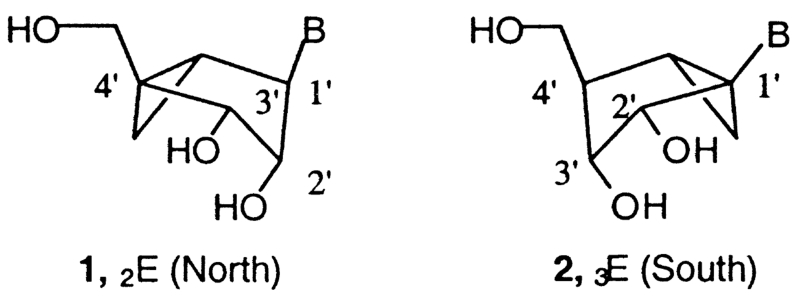

We have recently examined conformational requirements of the ribose moiety in adenosine agonists.7 In general, the ribose rings of nucleosides and nucleotides may adopt a range of conformations as described by the ‘pseudorotational cycle’.8 The northern [(N), 2′-exo] and southern [(S), 2′-endo] conformations are the most relevant to the biological activities observed for nucleosides and nucleotides in association with DNA, RNA, and various enzymes. We have defined a preference for the (N) conformation of ribose at both adenosine7 and P2Y receptors9 using methanocarba analogues in which a cyclopropane moiety constrains a pseudosugar (cyclopentane) ring of the nucleoside to either a (N)-, 1, or (S)-, 2, envelope conformation (Fig. 1). Such analogues have helped to define the role of sugar puckering in stabilizing the active adenosine receptor-bound conformation, and thereby have allowed identification of the (N) conformation as the favored isomer.

Figure 1.

In the present study, we have combined N6-substituted adenosine agonists containing the (N)-methanocarba modification with either 5′-uronamide groups or the 2′-deoxy modification. The 2′-deoxy modification is known to diminish agonist efficacy, to create partial agonists.10

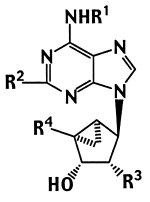

The structures of (N)-methanocarba adenosine analogues (3–17) synthesized and tested in binding assays at three subtypes of adenosine receptors11-13 are shown in Table 1. We combined the (N)-methanocarba modification of known potent adenosine agonists with either 5′-uronamide groups (5, 8, 14, and 16) or a 2′-deoxy modification (10, 12, and 17). These adenosine agonists contain methyl (6–8), cyclopentyl (9–12), or 3-iodobenzyl (13–17) substitution at the N6-position. Both 2-H and 2-Cl analogues are included. Several of the compounds, that is the triols 9, 11, 13, and 15, were reported to be selective adenosine agonists in a previous study.7

Table 1.

Affinities of methanocarba-adenosine analogues of the N-conformation and their 2′-deoxy analogues in radioligand binding assays at rat A1,a rat A2A,b and human A3 receptors,c unless notedd

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

|

Ki (nM) or % displacement |

|||||||

| Compd | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | rA1a | rA2Ab | hA3c |

| 3 | H | H | OH | CH2OH | 1680±80 | 22,500±100 (human) | 404±70e |

| 4 | H | Cl | OH | CH2OH | 273±36 | 1910±240 | 84.7±18.7 |

| 5 | H | H | OH | CONHCH2CH3 | 31.8±6.9 | 100±18 | 29.9±6.8 |

| 6 | Me | H | OH | CH2OH | 1470±190 | ≤10% at 10 μM | 126±18 |

| 7 | Me | Cl | OH | CH2OH | 884±99 | ≤10% at 10 μM | 22.5±7.4 |

| 8 | Me | Cl | OH | CONHCH3 | 805±197 | ≤10% at 10 μM | 6.19±0.42 |

| 9 | CP | H | OH | CH2OH | 5.06±0.51 | 6800±1800 | 170±51 |

| 10 | CP | H | H | CH2OH | 5110±790 | 15% at 100 μM | 2880±910 |

| 11 | CP | Cl | OH | CH2OH | 8.76±0.81 | 3390±520 | 466±58 |

| 12 | CP | Cl | H | CH2OH | 3600±780 | 45±5% at 100 μM | 1090±190 |

| 13 | IB | H | OH | CH2OH | 69.2±9.8 | 601±236 | 4.13±1.76 |

| 14 | IB | H | OH | CONHCH3 | 52.7±5.2 | 548±115 | 2.39±0.54 |

| 15 | IB | Cl | OH | CH2OH | 141±22 | 732±207 | 2.24±1.45 |

| 16 | IB | Cl | OH | CONHCH3 | 83.9±10.3 | 1660±260 | 1.51±0.23 |

| 17 | IB | Cl | H | CH2OH | 8730±370 | 25,400±3800 | 912±29 |

Displacement of specific [3H]R-PIA binding to A1 receptors in rat brain membranes, expressed as Ki±SEM (n = 3–5).

Displacement of specific [3H]CGS 21680 binding to A2A receptors in rat striatal membranes, expressed as Ki±SEM (n = 3–6), and at A2B receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells versus [3H]ZM241,385, unless noted.

Displacement of specific [125I]AB-MECA binding at human A3 receptors expressed in CHO cells, in membranes, expressed as Ki±SEM (n = 3–4).

Me, methyl; CP, cyclopentyl; IB, 3-iodobenzyl.

Measured in the absence of adenosine deaminase.

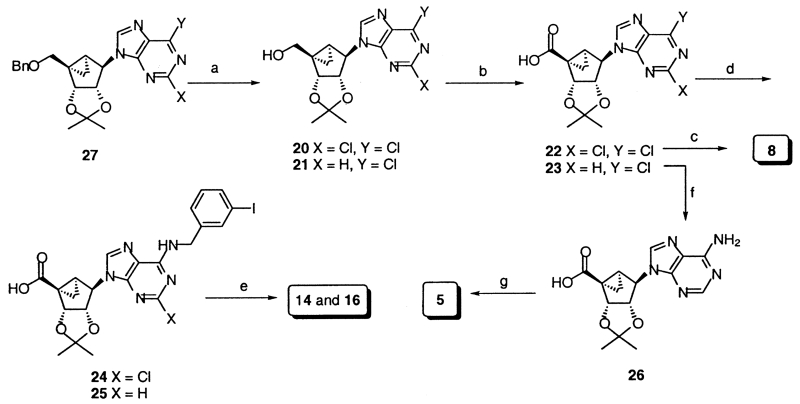

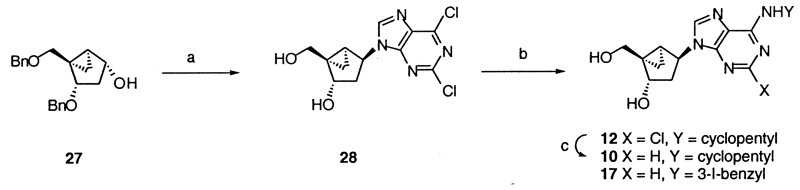

The synthetic methods used to prepare the new 5′-uronamide analogues are shown in Scheme 1. Nucleoside analogues, 20 and 21, containing a 6-Cl and a 5′-OH group, and protected as the 2′,3′-acetonides, were oxidized using basic sodium periodate and ruthenium tetraoxide. The resulting carboxylic acid derivatives, 23–25,14 were substituted at the 6-position by amine treatment, converted to the acid chloride using oxalyl chloride, and reacted immediately with methyl- or ethylamine to form 5′-uronamides.15 In the case of an N6-methyl 5′-uronamide derivative, the substitution of the 6-Cl and the formation of the uronamide from 22 were carried out in a single step, using a carbodiimide condensing reagent, to yield, after deprotection, 8.16 2′-Deoxy analogues were synthesized by the methods reported earlier9 via the (N)-methanocarba analogue of 2,6-dichloropurine-2′-deoxyriboside, 28, as an intermediate (Scheme 2).17

Scheme 1.

(a) (i) BCl3, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; (ii) p-TsOH, DMP, acetone; (b) NaIO4, RuO2, K2CO3, MeCN/CHCl3/H2O=2:2:3; (c) (i) EDAC, DMAP, MeNH3, CH2Cl2/DMF=1:1; (ii) 10% CF3CO2H/MeOH, H2O; (d) 3-I-benzylamine.HCl, TEA, MeOH; (e) (i) (COCl)2, 50 °C, then MeNH2, CH2Cl2; (ii) 10% CF3CO2H/MeOH, H2O; (f) NH3/2-propanol, 90 °C; (g) (i) (COCl)2, 50 °C, then EtNH2, CH2Cl2; (ii) 10% CF3CO2H/MeOH, H2O, 60 °C.

Scheme 2.

(a) (i) 2,6-Di-Cl-purine, DEAD, PPh3, THF; (ii) BCl3, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (b) cyclopentylamine (for 12) or 3-I-benzylamine.HCl, TEA (for 17), MeOH; (C) H2/Pd–C, MeOH.

In binding assays at A1, A2A, and A3ARs, the (N)-methanocarba analogue of 2-chloroadenosine, 4, in comparison to the (N)-methanocarba adenosine, 3, reported earlier,7 showed substantial enhancement of affinity at all three subtypes and displayed mixed A1/A3AR selectivity. The (N)-methanocarba analogue, 5, of the potent, nonselective agonist NECA (5′-N-ethyl-uronamidoadenosine) was slightly selective for A1 and A3ARs versus the A2AAR. For this 6-NH2 analogue, the 5′-uronamide, 5, enhanced affinity at the A1AR by 53-fold and at the A3AR by only 14-fold in comparison to the triol, 3.

In the series of N6-methyl derivatives, binding at A2AARs was absent, and the simple 4′-CH2OH compounds, 6 and 7, were selective in binding at the A3 versus A1AR by 12- and 39-fold, respectively. Compound 8 displayed a 4-fold increase in affinity at the A3AR over 7, and consequently 130-fold selectivity versus A1AR. The 5′-uronamide-modified N6-(3-iodobenzyl) analogues, 14 and 16, maintained affinity at A1 and A3ARs and, therefore, selectivity for A3 receptors. With an N6-methyl substituent, the 5′-uronamide modification enhanced affinity at the A3AR. The 2′-deoxy modified N6-cyclopentyl analogues, 10 and 12, bound weakly to adenosine receptors and were nonselective. The 2′-deoxy modified N6-(3-iodobenzyl) analogue, 17, displayed greatly reduced affinity and selectivity for the A3AR.

Agonist efficacy of selected adenosine derivatives was determined in a functional assay consisting of stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S by activation of human A1 and A3ARs.7,18 EC50 values for 10 and 12 at the A1AR were 2.89±0.14 μM (30±1% efficacy) and 2.28±0.99 μM (40±8% efficacy), respectively. Thus these two 2′-deoxy analogues, 10 and 12, were weak, partial agonists at the A1AR. EC50 values (nM) at the A3AR were: 25.5±6.1 (8), 6.80±1.95 (14), 5.25±2.20 (16), and 303±93 (NECA), and all four derivatives reached full agonist efficacy.

As reported previously,7 (N)-methanocarba analogues, such as 9, 13, and 15, containing various N6-substituents, in which the parent compounds were potent agonists at either A1 (e.g., cyclopentyl) or A3ARs (e.g., 3-iodobenzyl), retained the selectivity of the parent compound, especially at the A3AR. As before, the present ‘ribose-like’ (N)-methanocarba analogues (2′-OH) had preserved or enhanced A3AR affinity. For example, 5 was 6-fold more potent than the ribose equivalent at the A3AR and slightly less potent at A1 and A2AARs. The efficacy in present compound was reduced at A1AR for 2′-deoxy analogues (10 and 12) and increased at A3AR for 5′-uronamides (14 and 16).

In this study, we have introduced a new synthetic route for the oxidation of the 5′-carbon in the (N)-methanocarba series. This has allowed us to extend the SAR to include a modification that is generally potency-enhancing in the ribose series (i.e., 5′-uronamide). With a bulky N6-substituent (3-iodobenzyl), the A3AR affinity-enhancing effects of (N)-methanocarba and 5′-uronamide groups were not additive. Since the 5′-uronamide modification had either unchanged (for a large N6-substituent) or enhanced (for a small N6-substituent, methyl) affinity at the A3AR, we may conclude that in this series, requirements for N6- and 5′-substitutions are interrelated (i.e., non-independent in receptor binding). Another small substituent at the N6-position (MeONH−), when combined with modified 5′-groups, resulted in A3AR-selective agonists.19 Compound 8 (MRS 2346) was 130-fold selective for the A3 versus A1AR, illustrating again that a bulky N6-substituent was not required to achieve A3AR selectivity. Compound 16 (MRS 1898) was a potent and selective full agonist at the human A3AR.

In conclusion, the (N)-methanocarba modification has provided new analogues having A3AR selectivity, such as 8, and mixed A1/A3AR selectivity. The pharmacological properties of these analogues as agonists or partial agonists of adenosine receptors may now be studied.

References and Notes

- 1.Fredholm BB, Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Dubyak GR, Harden TK, Jacobson KA, Schwabe U, Williams M. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson KA, Knutsen LJS. In: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Abbracchio MP, Williams M, editors. 151/I. Springer; Berlin: 2001. pp. 301–383. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang BT, Jacobson KA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:6995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Lubitz DKJE, Lin RC-S, Popik P, Carter MF, Jacobson KA. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;263:59. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okusa MD, Linden J, Macdonald T, Huang L. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:F404. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.3.F404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller CE. Curr. Med. Chem. 2000;7:1269. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson KA, Ji X-D, Li AH, Melman N, Siddiqui MA, Shin KJ, Marquez VE, Ravi RG. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:2196. doi: 10.1021/jm9905965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marquez VE, Siddiqui MA, Ezzitouni A, Russ P, Wang J, Wagner RW, Matteucci MD. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:3739. doi: 10.1021/jm960306+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nandanan E, Jang SY, Moro S, Kim H, Siddiqui MA, Russ P, Marquez VE, Busson R, Herderwijn P, Harden TK, Boyer JL, Jacobson KA. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:829. doi: 10.1021/jm990249v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Der Graaf PH, Van Schaick EA, Mathôt RA, IJzerman AP, Danhof M. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;283:809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwabe U, Trost T. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1980;313:179. doi: 10.1007/BF00505731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis MF, Schutz R, Hutchison AJ, Do E, Sills MA, Williams M. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:978. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.General procedure for the 5′-carboxylic acid derivatives (22–23). To a solution of alcohol 20 (156 mg, 0.405 mmol) in CH3CN/CHCl3/H2O (14 mL, 2:2:3) were added sodium periodate (1.73 g, 8.1 mmol), ruthenium dioxide (40 mg), and potassium carbonate (40 mg), and the mixture was stirred for 24 h and filtered through filter paper. The filtrate was diluted with CH2Cl2 and H2O, and the water layer was separated. The combined water layer was acidified with concd HCl to pH 5–6 at 0°C. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 and the combined organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered and concentrated to dryness to give the acid 22 as colorless oil (151.8 mg, 97.3%). 22: 1H NMR (CD3Cl, 300 MHz) δ 8.11 (s, 1H), 5.87 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (s, 1H), 4.72 (d, J=6.9 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (s, 1H), 1.88 (m, 1H), 1.66 (m, 1H). MS (FAB) m/z 385 (M++1). 23: 1H NMR (CD3Cl, 300 MHz) δ 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 5.91 (d, J=6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 4.79 (d, J=6.9 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 1H), 1.86 (m, 1H), 1.67 (m, 1H). MS (NCI): m/z 350 (M−).

- 15.General procedure for the 5′-uronamide derivatives 5, 14, and 16. A stirred mixture of the acid 22 (76.3 mg, 0.131 mmol) and oxalyl chloride (1.4 mL) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) was heated at 60 °C for 2 h. After removal of the excess solvent and reagent under N2, the residue was suspended in anhyd CH2Cl2 and treated with methylamine (2 M in THF; in the case of 5, 2 M ethylamine/THF). The resulting mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h and poured into ice-cold water, which was extracted with CH2Cl2. After usual workup, the residue was purified on preparative TLC (CH3Cl/MeOH=15:1) to provide the amide intermediate (52.6 mg, 67.5%). The mixture of amide intermediate (14.7 mg, 0.025 mmol) having an acetonide group, 10% trifluoroacetic acid/MeOH (3 mL), and H2O (0.3 mL) was heated at 60 °C for 4 h. The solvent was removed and coevaporated with toluene. The residue was purified on silica gel to give the free amide 14 (12.2 mg, 89%). 14: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δ 8.21 (s, 1H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.58 (m, 1H), 7.36 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (d, J=5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 4.60 (d, J=4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J=6 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (m), 2.67 (d, J=4.2 Hz, 3H), 1.82 (m, 1H), 1.60 (m, 1H), 1.29 (m, 1H). HRMS (FAB) calcd 555.0408, found 555.0418. 16: 1H NMR (CD3OD, 300 MHz) δ 8.90 (t, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.58 (m, 1H), 7.36 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (d, J=5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 4.60 (d, J=4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (d, J=6 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (m), 2.67 (d, J=4.2 Hz, 3H), 1.82 (m, 1H), 1.60 (m, 1H), 1.29 (m, 1H). HRMS (FAB) calcd 521.0798, found 521.0814. 5: 1H NMR (CD3OD, 300 MHz) δ 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.23 (s, 1H), 5.15 (d, J=6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.41–5.05 (m), 4.13 (d, J=6.3 Hz, 1H), 2.19 (m, 1H), 1.97 (m, 1H), 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.30 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 3H). UV (MeOH) λmax 260.0 nm. HRMS (FAB) calcd 319.1519, found 319.1510.

- 16.Procedure for the preparation of the N6-methylamino-5′-uronamide, 8. A mixture of the acid 23 (19.9 mg, 0.052 mmol), DMAP (2.1 mg, 0.017 mmol), EDAC (1-[3-(dimethylamino)-propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide·HCl, 13 mg, 0.068 mmol), and methylamine (2 M in THF, 0.034 mL, 0.068 mmol) was stirred for 2.5 h at rt. The reaction mixture was concentrated to dryness and the residue was then washed with water. The organic layer was dried, filtered and dried to dryness, which was purified on preparative TLC (CH3Cl/MeOH=15:1) to give the amide intermediate (10 mg, 49%). 1H NMR (CD3Cl, 300 MHz) δ 7.70 (s, 1H), 6.91 (br s, 1H), 6.26 (br s, 1H), 5.66 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (m, 2H), 3.18 (d, 3H), 2.92 (d, J=5.1 Hz, 3H), 2.93 (s, 3H), 2.91 (s, 3H). HRMS (FAB) calcd 393.1442, found 393.1446. A mixture of amide intermediate (5.2 mg, 0.013 mmol) having an acetonide group, 10% trifluoroacetic acid/MeOH (1 mL), and H2O (0.1 mL) was heated at 60 °C for 4 h. The solvent was removed and coevaporated with toluene. The residue was purified on silica gel (CH3Cl/MeOH=12:1) to give the free amide 8 (3.8 mg, 85%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δ 8.06 (s, 1H), 5.43 (d, J=4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (t, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 4.12 (m, 2H), 3.87 (m, 1H), 2.91 (d, 3H), 2.66 (d, J=4.2 Hz, 3H), 1.81 (m, 1H), 1.60 (m, 1H), 1.35 (m, 1H). UV (MeOH) λmax 271.0 nm. HRMS (FAB) calcd 353.1129, found 353.1139.

- 17.To a mixture of 2720 (0.25 g, 0.77 mmol), dichloropurine (0.29 g, 1.54 mmol), and triphenylphosphine (0.4 g, 1.54 mmol) in anhydrous THF (10 mL) was added DEAD drop-wise at 0 °C with stirring for 6 h. Solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue obtained was purified using flash chromatography using 7:3 petroleum ether/ethyl acetate to furnish 0.25 g of protected product. This compound (0.19 g, 0.38 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and treated with1 M BCl3 in CH2Cl2 (1.14 mL, 1.14 mmol) at 0 °C and stirred for 15 min for complete reaction. Solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue obtained was purified by flash chromatography using 10% MeOH in CHCl3 to furnish 0.13 g of product 28. To a solution of 28 (0.025 g, 0.08 mmol) in MeOH (2 mL), was added cyclopentylamine (0.04 mL, 0.4 mmol) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 8 h. Solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue was purified by flash chromatography using 5% MeOH in CHCl3 to furnish 0.023 g of product 12: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.02 (s, 1H, C-8), 6.22 (bs, 1H), 5.16 (t, 1H, J=7.81 Hz), 4.58 (s, 1H), 4.25 (d, 1H, J=11.72 Hz), 3.50 (d, 1H, J=11.72 Hz), 2.17–2.10 (m, 3H), 1.95–1.85 (m, 1H), 1.76–1.52 (m, 7H), 1.0–0.74 (m, 3H). HRMS (FAB) calcd 364.1540, found 364.1549. To a solution of 12 in MeOH (10 mL) was added 10% Pd/C (4 mg) and stirred under H2 at atmospheric pressure. Solvent was removed, and the residue was purified by preparative TLC 10% MeOH in CHCl3 to furnish 10 mg of 10: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.49 (s, 1H, C-8), 8.23 (s, 1H, C-2), 5.03 (d, 1H, J=6 Hz) 4.58 (d, 1H J=12 Hz), 4.29 (d, 1H, J=11.53 Hz), 3.34 (d, 1H, J=11.53 Hz), 2.2–1.98 (m, 4H), 1.92–1.6 (m, 8H), 1.1–1.0 (m, 1H), 0.98–0.75 (m, 1H). HRMS (FAB) calcd 330.1930, found 330.1941. To a solution of 28 (0.025 g, 0.08 mmol) in MeOH (2 mL) was added 3-iodobenzylamine hydrochloride (0.1 g, 0.4 mmol) and triethylamine (0.056 mL, 0.4 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 6 h. Solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue was purified using flash chromatography using 5% MeOH in CHCl3 to furnish 0.03 g of 17: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.46 (s, 1H, C-8), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, 1H, J=7.81 Hz), 7.39 (d, 1H, J=7.81 Hz), 7.09 (t, 1H, J=7.81 Hz), 4.96 (d, 1H, J=5.86 Hz), 4.7 (s, 2H), 4.27 (d, 1H, J=11.72 Hz), 3.36 (d, 1H, J=11.72 Hz), 2.1–1.96 (m, 1H), 1.9–1.7 (m, 1H), 1.7–1.6 (m, 1H), 1.04–1.01 (m, 1H), 0.82–0.74 (m, 1H). HRMS (FAB) calcd 512.0350, found 512.0358.

- 18.Lorenzen A, Guerra L, Vogt H, Schwabe U. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;49:915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mogensen JP, Roberts SM, Bowler AN, Thomsen C, Knutsen LJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:1767. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marquez VE, Russ P, Alonso R, Siddiqui MA, Hernandez S, George C, Nicklaus MC, Dai F, Ford H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1999;82:2119. doi: 10.1080/15257779908041487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]