Abstract

Recent studies using knock-out mice for various secreted phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) isoforms have revealed their non-redundant roles in diverse biological events. In the skin, group IIF sPLA2 (sPLA2-IIF), an “epidermal sPLA2” expressed in the suprabasal keratinocytes, plays a fundamental role in epidermal-hyperplasic diseases such as psoriasis and skin cancer. In this study, we found that group IIE sPLA2 (sPLA2-IIE) was expressed abundantly in hair follicles and to a lesser extent in basal epidermal keratinocytes in mouse skin. Mice lacking sPLA2-IIE exhibited skin abnormalities distinct from those in mice lacking sPLA2-IIF, with perturbation of hair follicle ultrastructure, modest changes in the steady-state expression of a subset of skin genes, and no changes in the features of psoriasis or contact dermatitis. Lipidomics analysis revealed that sPLA2-IIE and -IIF were coupled with distinct lipid pathways in the skin. Overall, two skin sPLA2s, hair follicular sPLA2-IIE and epidermal sPLA2-IIF, play non-redundant roles in distinct compartments of mouse skin, underscoring the functional diversity of multiple sPLA2s in the coordinated regulation of skin homeostasis and diseases.

Keywords: fatty acid, lipid metabolism, lysophospholipid, Phospholipase A, skin

Introduction

Lipids constitute an essential component of skin homeostasis and diseases. The epidermis is a highly organized stratified epithelium having four distinctive layers comprising the innermost stratum basale, the stratum spinosum, the stratum granulosum, and the outermost stratum corneum (SC)2 (1). The hair follicle, a skin appendage formed by interactions between epidermal keratinocytes committed to hair follicle differentiation and dermal fibroblasts committed to formation of the dermal papilla, undergoes repeated cycles of growth (anagen), regression (catagen), and rest (telogen) during life span (2). Nutritional insufficiency of essential fatty acids causes epidermal and hair abnormalities (1), and genetic mutations in several steps of skin lipid metabolism variably and often severely affect SC barrier function or hair cycling, thereby causing or exacerbating skin disorders such as ichthyosis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia (3–6). Linoleic acid (LA), by far the most abundant polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) in the SC, is crucial for the formation of acylceramide, an essential component of the cornified lipid envelope (7, 8). Fatty acids have also been implicated in SC acidification (9–11). Furthermore, dysregulated production of lipid mediators derived from PUFAs or lysophospholipids can be linked to skin disorders such as hair loss, epidermal hyperplasia, dermatitis, and cancer (6, 12, 13).

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes hydrolyze the sn-2 position of phospholipids to release fatty acids and lysophospholipids, which act as precursors of a variety of lipid mediators. Of the PLA2 enzymes, cytosolic PLA2α plays a central role in eicosanoid generation by selectively releasing arachidonic acid (AA) (14, 15), and Ca2+-independent PLA2s are involved in energy metabolism and neurodegeneration (16, 17). Although the biological roles of the secreted PLA2 (sPLA2) family have remained unclear over the past few decades, recent studies using mice gene-manipulated for sPLA2 isoforms have revealed their diverse and non-redundant functions in immunity, host defense, atherosclerosis, obesity, cancer, and reproduction, etc. by driving unique lipid pathways in given extracellular microenvironments (18).

We have recently demonstrated that group IIF sPLA2 (sPLA2-IIF) is expressed predominantly in the suprabasal epidermis and that its genetic deletion perturbs keratinocyte differentiation and activation, particularly under pathological conditions such as psoriasis and skin cancer (19). This action of sPLA2-IIF as an “epidermal sPLA2” depends at least in part on the generation of plasmalogen lysophosphatidylethanolamine (P-LPE; lysoplasmalogen), a unique lysophospholipid that can promote keratinocyte activation and epidermal hyperplasia. Beyond sPLA2-IIF, transgenic overexpression of sPLA2-IIA or -X causes alopecia and epidermal hyperplasia (20, 21), although endogenous expression of these two sPLA2s as well as sPLA2-IB, -IID, and -V in mouse skin is low or almost undetectable (19).

sPLA2-IIE is an isoform structurally most homologous to sPLA2-IIA (22, 23). Although the expression, target phospholipids, and biological roles of sPLA2-IIE in vivo remained a mystery for more than a decade, we have recently shown that it is a diet-inducible, adipocyte-driven “metabolic sPLA2” that participates in metabolic regulation by acting on minor phospholipids in lipoprotein particles (24). In this study, we show for the first time that sPLA2-IIE is abundantly expressed in mouse skin, being enriched in hair follicles. Analyses of mice lacking sPLA2-IIE (Pla2g2e−/−), in comparison with those lacking sPLA2-IIF (Pla2g2f−/−), revealed distinct roles of these two sPLA2s in skin homeostasis and diseases.

Results

Expression of sPLA2-IIE in Mouse Skin

We have recently shown that sPLA2-IIE is highly expressed in hypertrophic adipocytes of obese mice (24). In a search of other mouse tissues in which sPLA2-IIE is expressed under steady-state conditions, we found that Pla2g2e mRNA (encoding sPLA2-IIE) was uniquely distributed in the uterus and skin at higher levels than in adipose tissue (Fig. 1A). The expression of sPLA2-IIE in the uterus had been reported previously (22), although Pla2g2e−/− mice, both male and female, did not show reproductive abnormality (data not shown). Therefore, in this study, we focused on the expression and function of this sPLA2 in mouse skin.

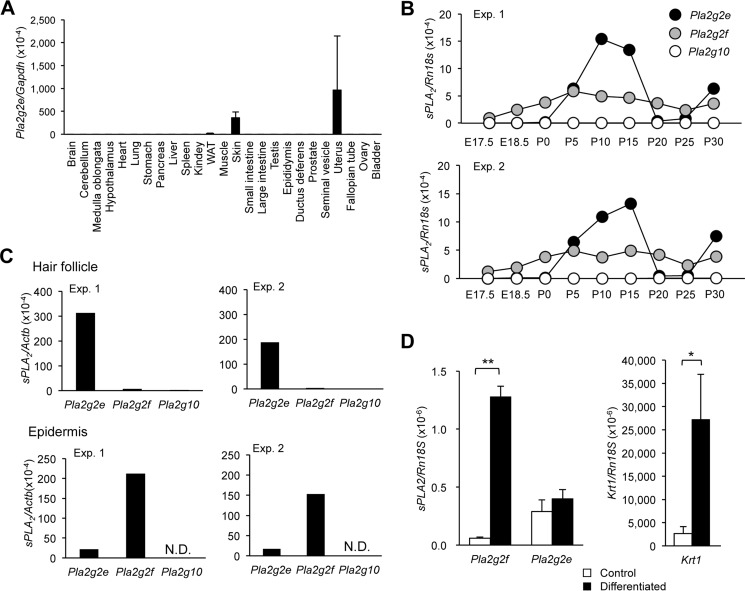

FIGURE 1.

Expression of sPLA2-IIE in mouse skin. A, quantitative RT-PCR of Pla2g2e in various tissues of 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice, with Gapdh as an internal control (n = 3). B, quantitative RT-PCR of sPLA2s in mouse skin over E17.5 to P30, with Rn18s as an internal control. C, quantitative RT-PCR of three sPLA2s in the epidermal and hair follicular fractions separated by microdissection, with Actb as an internal control. N.D., not detected. B and C, two representative results (Exp. 1 and 2) are shown. D, quantitative RT-PCR of sPLA2s and Krt1 in mouse keratinocytes with or without Ca2+-induced differentiation in primary culture, as detailed under “Experimental Procedures” (n = 3–5). Values are mean ± S.E., *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01.

As reported previously (19), Pla2g2f mRNA (encoding sPLA2-IIF) was expressed abundantly in mouse dorsal skin throughout the peri- to postnatal period (Fig. 1B). We noticed that, although the skin expression of Pla2g2e was low before birth, it increased markedly during P5–15, even exceeding the expression of Pla2g2f (Fig. 1B). Thereafter, the expression of Pla2g2e declined to nearly the basal level during P20–25 and then increased again to a level higher than that of Pla2g2f at P30. The periodic pattern of Pla2g2e expression appeared to coincide with the hair cycle, which involves repeated cycles of growth (anagen; P0–15), regression (catagen; P15–20), rest (telogen; P20–25), and re-growth (the next anagen; beyond P25), raising the possibility that sPLA2-IIE is expressed in hair follicles.

To address this issue, we separated the epidermis and hair follicles from frozen sections of mouse dorsal skin at P8 by microdissection. As expected (19), Pla2g2f was distributed in the epidermal fraction almost exclusively, whereas Pla2g2e was expressed in both fractions, with more abundant expression in the hair follicle fraction than in the epidermal fraction (Fig. 1C). Although Pla2g10 (encoding sPLA2-X) has been reported to be expressed in hair follicles in correlation with the hair cycle (21), its hair follicle expression, relative to that of Pla2g2e, was nearly negligible (Fig. 1C). Expression levels of other sPLA2s (IB, IID, and V) in hair follicles were minimal (19). Thus, sPLA2-IIE is the predominant sPLA2 expressed in hair follicles during anagen.

Because a substantial level of Pla2g2e expression was also detected in the epidermal fraction (Fig. 1C), we examined its expression in epidermal keratinocytes in primary culture. Ca2+-induced differentiation of primary keratinocytes from newborn WT mice resulted in robust induction of Pla2g2f in parallel with that of the keratinocyte differentiation marker Krt1 (Fig. 1D), as reported previously (19). In contrast, Pla2g2e expression in cultured keratinocytes was constant regardless of the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that, in contrast to sPLA2-IIF that is induced in differentiated keratinocytes (19), sPLA2-IIE is constantly expressed in undifferentiated basal keratinocytes.

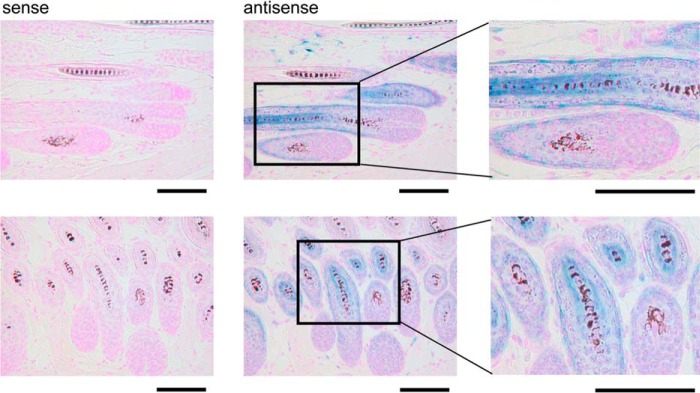

Consistent with the preferential distribution of Pla2g2e in hair follicles, in situ hybridization of Pla2g2e in mouse dorsal skin at 4 weeks, a period corresponding to the next anagen, confirmed its distribution in growing hair follicles but not in the dermal papilla (Fig. 2). High magnification images of the cross-sections of hair follicles revealed that the Pla2g2e signal was localized in the second outermost layer and the innermost layer surrounding the growing hair shafts. These results suggest the specific localization of sPLA2-IIE in companion cells of the outer root sheath (ORS) and cuticular cells of the inner root sheath (IRS) in hair follicles during anagen.

FIGURE 2.

In situ hybridization of Pla2g2e in mouse skin. In situ hybridization of Pla2g2e in mouse skin at 4 weeks using antisense and sense probes. Blue signal indicates the localization of Pla2g2e. Boxed areas in the middle panels are magnified in the right panels. Bars, 100 μm.

Skin Phenotypes in Pla2g2e−/− Mice

To assess the roles of sPLA2-IIE in mouse skin, we employed Pla2g2e−/− mice (24). Grossly, Pla2g2e−/− mice over 1 year of age under normal housing conditions had a normal appearance with no apparent skin abnormality. Histologically, the skins of both genotypes showed no apparent differences in the density and length of hair follicles, thickness of the dermis and epidermis, and organization of the subcutaneous fat layer between the skins of both genotypes at P33 (Fig. 3A). We noticed, however, that the upper part of growing hair follicles, where sPLA2-IIE was located (Fig. 2), appeared to be swollen in Pla2g2e−/− mice relative to Pla2g2e+/+ mice.

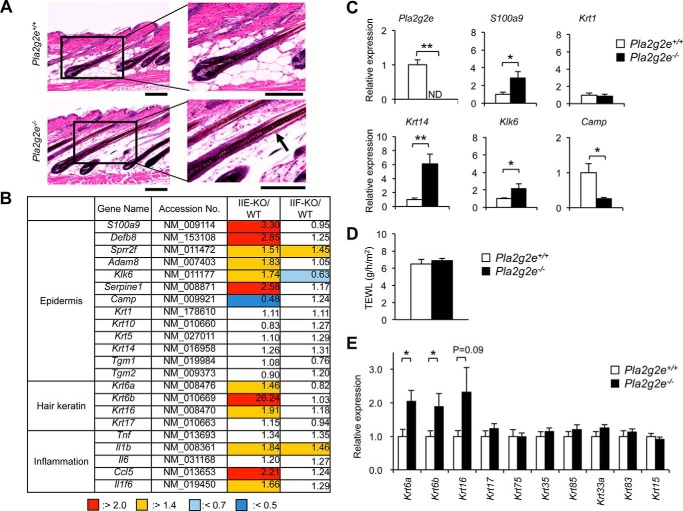

FIGURE 3.

Skin phenotypes in Pla2g2e−/− mice. A, hematoxylin and eosin staining of skin sections from Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− mice at P33. Boxed areas in the left panels are magnified in the right panels. An arrow indicates hair follicle swelling. B, microarray gene profiling of skins from Pla2g2e−/− (IIE-KO) and Pla2g2f−/− (IIF-KO) mice in comparison with WT mice at P33. The expression ratios (KO/WT) are shown. C, quantitative RT-PCR of various genes in Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− skins at P33, with expression in Pla2g2e+/+ skin as 1 (n = 5). D, TEWL of Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− mice at 8 weeks (n = 10). E, quantitative RT-PCR of various hair keratins in Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− skins at P33, with expression in Pla2g2e+/+ skin as 1 (n = 5). Values are mean ± S.E., *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01.

To clarify the subtle skin alterations caused by Pla2g2e ablation, we performed microarray analysis using Pla2g2e−/− skin in comparison with Pla2g2e+/+ skin at this stage. We also compared the gene expression profile in Pla2g2e−/− skin with that in age-matched Pla2g2f−/− skin, which displayed only modest epidermal abnormalities under normal conditions (19). Indeed, there were only a few alterations of gene expression in normal skin of Pla2g2f−/− mice relative to that of WT mice at this stage (Fig. 3B). Similarly to Pla2g2f−/− skin, the global gene expression profile was not profoundly affected in Pla2g2e−/− skin. We found, however, that the expression levels of a subset of genes (e.g. S100a9, Defb8, Sprr2f, Serpine1, Adam8, Klk6, Il1b, Il1f6, and Ccl5), which are reportedly elevated in response to epidermal stress (25–30), were substantially higher in Pla2g2e−/− skin than in control skin (Fig. 3B). The microarray results were further verified by quantitative RT-PCR, in which the expression of S100a9 and Klk6 was significantly higher, whereas that of Camp was lower, in Pla2g2e−/− skin than in Pla2g2e+/+ skin (Fig. 3C). Increased expression of Krt14, but not Krt1, in Pla2g2e−/− skin (Fig. 3C) implies that the lack of sPLA2-IIE has some influence on hair follicular and/or basal keratinocytes rather than on suprabasal keratinocytes. However, the state of the inside-out skin barrier, as assessed by transepidermal water loss (TEWL), did not differ between Pla2g2e−/− and Pla2g2e+/+ skins (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the modest changes in the expression of a subset of skin genes did not affect epidermal barrier function in Pla2g2e−/− mice.

Notably, expression of specific keratins (Krt16 and its partners Krt6a and Krt6b), which are preferentially distributed in the companion layer of hair follicles (31–33), was uniquely elevated in Pla2g2e−/− skin relative to Pla2g2e+/+ skin (Fig. 3B). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed the increased expression of Krt16, Krt6a, and Krt6b in Pla2g2e−/− skin relative to Pla2g2e+/+ skin, although the expression of other hair keratins was unaffected by Pla2g2e deficiency (Fig. 3E). Thus, in agreement with the main localization of sPLA2-IIE in hair follicles (Fig. 1), Pla2g2e−/− skin harbors some alterations in the expression of several, if not all, hair follicular genes.

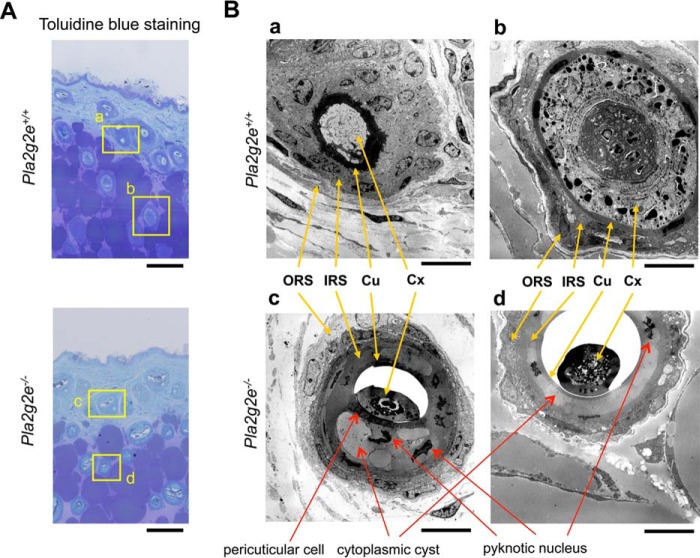

Transmission electron microscopy revealed notable abnormalities in hair follicles (Fig. 4, A and B), rather than epidermis (data not shown), in Pla2g2e−/− mice. The hair follicle consists of several distinctive layers as follows: ORS, companion layer, IRS (Henle's layer, Huxley's layer, and IRS cuticle), and hair shaft (cuticle, hair cortex, and medulla) from the outermost to innermost layers. In contrast to the well organized architecture of hair follicles in WT mice, those in Pla2g2e−/− mice had noticeable defects in the IRS and hair shaft (Fig. 4B). In hair follicles of Pla2g2e−/− skin, IRS cells contained large cytoplasmic cysts and pyknotic nuclei and were devoid of keratohyalin granules. Adjacent to the cuticle, Pla2g2e−/− mice had unusual pericuticular cells that were absent in WT mice, suggesting altered differentiation of hair follicular cells. Moreover, the cuticle in Pla2g2e−/− mice was abnormally dissociated from the hair cortex and medulla, which had an immature or regressed appearance. These results appear to be compatible with the swollen feature of Pla2g2e−/− hair follicles under the light microscope (Fig. 3A). Thus, the lack of sPLA2-IIE leads to hair follicle abnormalities.

FIGURE 4.

Transmission electron microscopy of Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− skins. A, toluidine blue staining of Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− skins. Boxed areas (panels a–d) are magnified in B. Bars, 100 μm. B, transmission electron microscopy of hair follicles in Pla2g2e+/+ (panels a and b) and Pla2g2e−/− (panels c and d) skins. Locations of ORS, IRS, cuticle (Cu), and cortex (Cx) are indicated by yellow arrows. Red arrows indicate abnormal features observed in Pla2g2e−/− mice (formation of cytoplasmic cysts and pyknotic nuclei in the IRS and the presence of pericuticular cells). In addition, the cuticle and cortex were unusually dissociated in Pla2g2e−/− mice. Bars, 10 μm.

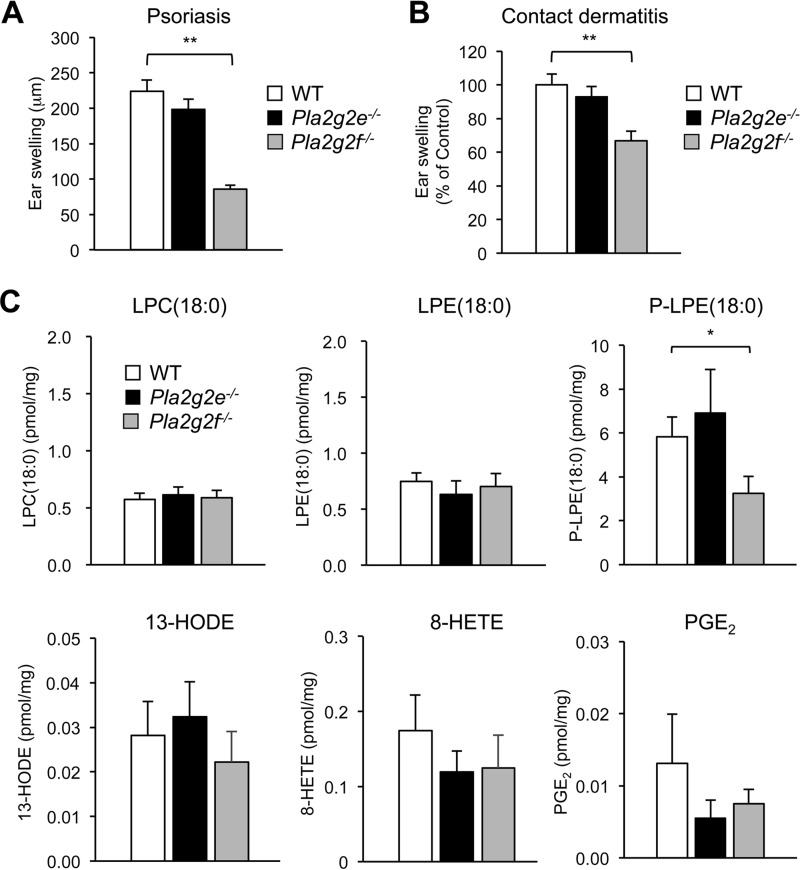

No Alterations of Psoriasis and Contact Dermatitis in Pla2g2e−/− Mice

In psoriasis and skin cancer, sPLA2-IIF is up-regulated in the thickened epidermis and promotes epidermal hyperplasia through production of the unique lysophospholipid P-LPE (19). Some alterations in Pla2g2e−/− skin under normal conditions (Figs. 3, 4) prompted us to examine the impact of Pla2g2e deficiency on these skin disorders. However, neither imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis nor dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB)-induced contact dermatitis was affected in Pla2g2e−/− mice in comparison with Pla2g2e+/+ mice (Fig. 5, A and B). This was in contrast to Pla2g2f−/− mice, where ear swelling was significantly ameliorated in both models. Moreover, although the level of P-LPE, a main metabolite produced by sPLA2-IIF, was selectively reduced in IMQ-treated Pla2g2f−/− skin relative to WT mice as reported previously (19), the levels of P-LPE as well as other lipid metabolites were similar in the psoriatic skins of Pla2g2e−/− and WT mice (Fig. 5C). Thus, unlike sPLA2-IIF that promotes epidermal hyperplasia (19), sPLA2-IIE plays a minimal role in these skin disorders, further emphasizing the functional segregation of these two sPLA2s in the skin.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of Pla2g2e or Pla2g2f deficiency on psoriasis and contact dermatitis. A and B, ear swelling of WT, Pla2g2e−/−, and Pla2g2f−/− mice after treatment with IMQ for 5 days (n = 6) (A) or with DNFB for 2 days (n = 10) (B). C, quantitative lipidomics of lipid metabolites in skins of WT, Pla2g2e−/−, and Pla2g2f−/− mice after treatment for 5 days with IMQ (n = 7–16). The methods for IMQ-induced psoriasis and DNFB-induced contact dermatitis are detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” Values are mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01. HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

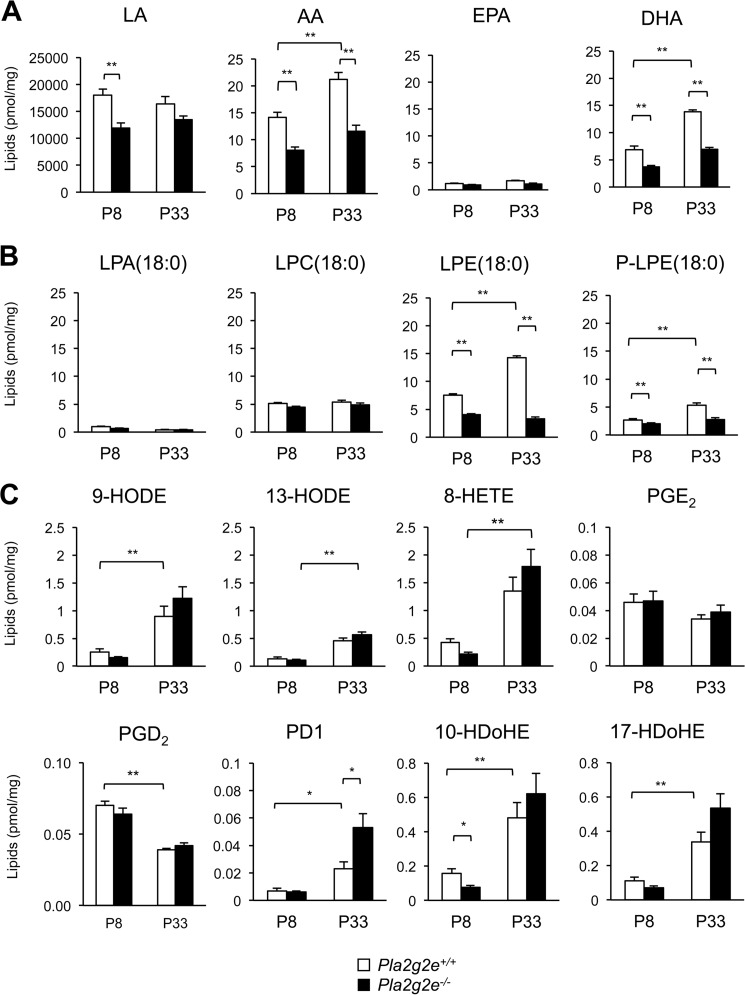

sPLA2-IIE-dependent Lipid Metabolism in Mouse Skin

To identify the lipid metabolism that potentially lies downstream of sPLA2-IIE in mouse skin, we performed electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) lipidomics analysis using Pla2g2e−/− mice in comparison with littermate WT mice at P8 and P33, at which time (corresponding to the initial and next anagens, respectively) sPLA2-IIE expression in the skin was very high (Fig. 1B). We found that the skin levels of free PUFAs, including LA, AA, and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), were significantly lower in Pla2g2e−/− mice than in age-matched Pla2g2e+/+ mice (Fig. 6A). Among the lysophospholipids, there were notable reductions of the acyl and plasmalogen forms of LPE in Pla2g2e−/− skin relative to age-matched Pla2g2e+/+ skin, although the levels of other lysophospholipids, including lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), were not profoundly affected by Pla2g2e deficiency (Fig. 6B). Despite the decreases of free PUFAs in Pla2g2e−/− skin, however, the levels of various PUFA metabolites, many if not all of which increased with age probably due to increased expression of epidermal lipoxygenases (34), did not differ significantly between the genotypes, except that 10-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid was lower at P8 and protectin D1 was greater at P33 in Pla2g2e−/− skin than in WT skin (Fig. 6C). Although the reason for a trend toward the increase of protectin D1 at P33 in Pla2g2e−/− skin relative to WT skin is unknown, it might reflect a compensatory response. Phospholipid species did not noticeably differ between the genotypes (data not shown), likely because high background levels of phospholipids in membranes of the whole skin masked their local changes by sPLA2s in a subset of cells. Altogether, these results suggest that sPLA2-IIE mobilizes various PUFA and LPE species, but with few effects on PUFA metabolites, in mouse skin.

FIGURE 6.

Lipidomics analysis of Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− skins. Lipids extracted from Pla2g2e+/+ and Pla2g2e−/− skins at P8 or P33 were subjected to ESI-MS for unsaturated fatty acids (A), lysophospholipids (B), and PUFA metabolites (C) (n = 7–8). Values are mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01. PGD2, prostaglandin D2; PD1, protectin D1; HDoHE, hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid.

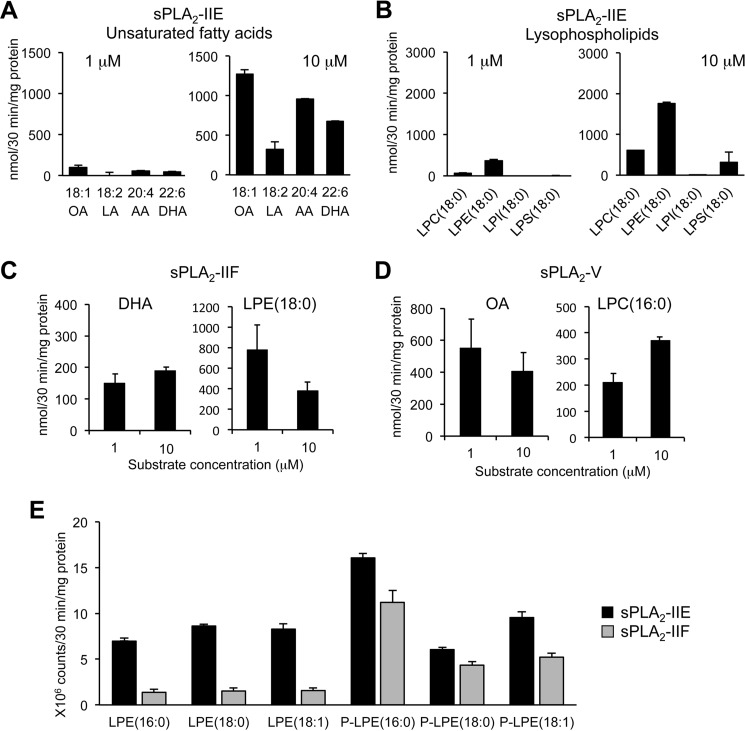

Enzymatic Properties of sPLA2-IIE toward Skin-extracted Phospholipids

The enzymatic activity of sPLA2-IIE has remained controversial. Suzuki et al. (23) have shown that the activity of sPLA2-IIE is nearly comparable with that of sPLA2-IIA, being capable of hydrolyzing phosphatidylethanolamine and to a lesser extent phosphatidylcholine with no fatty acid selectivity, whereas Valentin et al. (22) have reported that the activity of sPLA2-IIE is much weaker than that of other sPLA2s. To assess whether sPLA2-IIE is indeed able to release PUFAs and LPEs from skin phospholipids, we incubated recombinant sPLA2-IIE with two different concentrations of skin-extracted phospholipids in vitro. We found that the activity of sPLA2-IIE was robust when the substrate concentration was high (10 μm), whereas it was very weak at a low substrate concentration (1 μm) (Fig. 7, A and B). In the presence of 10 μm substrate, sPLA2-IIE released various unsaturated fatty acids, including oleic acid, LA, AA, and DHA, as well as LPE(18:0) in preference to LPC(18:0) (Fig. 7, A and B). In comparison, sPLA2-IIF and sPLA2-V were sufficiently active even at 1 μm substrate (Fig. 7, C and D), as monitored by the release of their preferred fatty acids (DHA and oleic acid, respectively) and lysophospholipids (LPE(18:0) and LPC(18:0), respectively) (19, 24). As for LPE molecular species, sPLA2-IIE released various LPE species (acyl and plasmalogen forms), whereas sPLA2-IIF tended to release P-LPE in preference to acyl-LPE (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that sPLA2-IIE is as active as other sPLA2s if the phospholipid concentration is high enough or that the skin-extracted phospholipid preparation used in this assay might have contained a certain substance that enhances the activity of sPLA2-IIE. The overall enzymatic properties of sPLA2-IIE observed here are roughly reminiscent of those reported by Suzuki et al. (23) and are consistent with the lipid profiles that are altered in Pla2g2e−/− skin in vivo (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 7.

In vitro enzymatic activity of sPLA2-IIE. A and B, release of fatty acids (A) and lysophospholipids (B) from skin-extracted phospholipids (1 or 10 μm) after incubation for 30 min with 40 ng/ml recombinant sPLA2-IIE (n = 3). C and D, release of the indicated lipids from skin-extracted phospholipids (1 or 10 μm) by 40 ng/ml recombinant sPLA2-IIF (C) or sPLA2-V (D) (n = 3). E, release of various LPE species from skin-extracted phospholipids (10 μm) after incubation with sPLA2-IIE or sPLA2-IIF (n = 3). Values are mean ± S.E. LPI, lysophosphatidylinositol; LPS, lysophosphatidylserine.

Discussion

Our recent study using Pla2g2f-deficient and -transgenic mice, in combination with PLA2-directed lipidomics toward phospholipids (substrate) as well as fatty acids, lysophospholipids, and their metabolites (products), has revealed a unique and novel lysophospholipid pathway driven by sPLA2-IIF that promotes keratinocyte activation and epidermal hyperplasia (19). In this study, we have identified sPLA2-IIE as the second sPLA2 that is abundantly expressed in mouse skin. Unlike sPLA2-IIF, an epidermal sPLA2 that is expressed in differentiated epidermal keratinocytes (19), sPLA2-IIE is regarded as a “hair follicular sPLA2” that is enriched in hair follicles in the anagen phase of hair cycling.

So far, except for its metabolic role in diet-induced obesity in adipose tissue (24), sPLA2-IIE is an ill-characterized sPLA2 whose expression, enzymatic properties, and in vivo functions remain poorly understood. Our present finding that sPLA2-IIE is abundantly expressed in mouse skin (at an even higher level than sPLA2-IIF during anagen), together with the fact that sPLA2-IIE (as is sPLA2-IIF, but not other sPLA2s) is enzymatically active at a mildly acidic pH relevant to the skin microenvironment (22), suggests that sPLA2-IIE plays some roles in skin pathophysiology. It should be noted, however, that the skin compartments in which sPLA2-IIE and -IIF are localized are distinct. sPLA2-IIF is expressed in the suprabasal epidermis and is dramatically up-regulated during terminal differentiation or activation of keratinocytes (19), whereas sPLA2-IIE is expressed constantly in basal keratinocytes. More importantly, sPLA2-IIE is expressed in hair follicles much more abundantly than in the epidermis and in fact sPLA2-IIE is the primary hair follicular sPLA2 whose expression is correlated with hair cycling. These distributions suggest distinct, rather than redundant, roles of these two sPLA2s in specific compartments of the skin.

Although grossly Pla2g2e−/− mice have a nearly normal appearance, their hair follicles display several abnormalities in terms of ultrastructure and gene expression profile. These abnormalities include the presence of unusual cytoplasmic cysts in the IRS, dissociation of the cuticle from the hair cortex, immaturity or regression of the hair shaft, and altered expression of a subset of keratins associated with the companion layer. Notably, sPLA2-IIE is located in these affected regions (the innermost IRS layer and the companion layer along growing hairs) within hair follicles, lending further support to the idea that sPLA2-IIE regulates hair follicle homeostasis at these restricted locations. We previously reported that Pla2g10-transgenic mice displayed alopecia with perturbed hair cycling and that Pla2g10−/− mice showed ORS hypoplasia (21). However, the very low expression of endogenous sPLA2-X in mouse skin argues against its hair follicle-intrinsic role. Rather, we prefer the idea that sPLA2-X expressed in distal locations, such as the gastrointestinal tract (35, 36), might indirectly affect hair follicle homeostasis through nutritional or other mechanisms.

In the epidermis, sPLA2-IIF is expressed more abundantly than sPLA2-IIE. Pla2g2f deficiency increases TEWL (indicating a skin barrier defect) due to SC fragility against environmental stress (19) but with only a few changes in the steady-state expression of skin genes under normal conditions. In contrast, Pla2g2e ablation leads to increased (albeit modest) expression of a panel of genes for the epidermal stress response, without alteration of TEWL. Furthermore, Pla2g2f−/− mice display attenuated psoriasis or contact dermatitis with a concomitant reduction of the lysophospholipid P-LPE (19), whereas skin edema and lipid profiles in these disease models are barely affected in Pla2g2e−/− mice. These differences can be explained, at least in part, by distinct localizations of these two sPLA2s in skin niches (see above) as well as by their distinct substrate specificities (see below), which could have different impacts on epidermal homeostasis and diseases. This view also contrasts with the exacerbation of psoriasis and contact dermatitis with augmented Th1/Th17 immune responses in mice lacking sPLA2-IID, a “resolving sPLA2” that is expressed in dendritic cells and regulates the functions of immune cells rather than keratinocytes by producing ω3 PUFA-derived pro-resolving lipid mediators (37, 48).

In contrast to sPLA2-IIF, which selectively mobilizes P-LPE in psoriatic skin (19), sPLA2-IIE appears to mobilize various unsaturated fatty acids and LPEs (both acyl and plasmalogen forms) in normal skin. Consistent with these in vivo data, sPLA2-IIE releases these fatty acids and LPEs in an in vitro enzyme assay using a skin-extracted phospholipid mixture as a substrate. Given its spatiotemporal localization, it is tempting to speculate that sPLA2-IIE supplies unsaturated fatty acids and LPEs in hair follicles during anagen. It has been reported that several PUFA metabolites (e.g. prostaglandins) or LPA variably affect hair growth, quality, and cycling (13, 38–41). However, the skin levels of PUFA metabolites and LPA are not profoundly affected by Pla2g2e deficiency, indicating that sPLA2-IIE-derived PUFAs are largely uncoupled with downstream lipid mediators. The issue of whether PUFAs themselves, LPEs, or some other lipid metabolites not examined in this study underlie sPLA2-IIE-regulated hair follicle homeostasis will require further investigation.

The assessment of in vitro enzyme activity using recombinant sPLA2 is influenced by the assay conditions employed, such as the composition of the substrate phospholipids (pure phospholipid vesicles or mixed micelles comprising multiple phospholipid species), the concentrations of sPLA2, the presence of detergents, pH, and so on. Therefore, the enzymatic properties of sPLA2s determined in different studies are not entirely identical (22, 23). Because membranes containing a single phospholipid species do not exist in vivo, a result obtained using artificial phospholipid membranes may not mirror the in vivo actions of a given sPLA2. Ideally, sPLA2 activity should be evaluated with a physiologically relevant membrane on which the enzyme acts intrinsically, as we have recently reported for sPLA2-IIF (19). Nonetheless, the overall selectivity of sPLA2s for various phospholipid headgroups and fatty acyl chains has been recapitulated by several in vitro enzymatic studies, and the in vivo lipidomics data have revealed even more selective patterns of hydrolysis (19, 24, 36, 37). Although the local concentration of sPLA2-IIE in hair follicles is unclear, our present results obtained from the in vitro and in vivo lipidomics approaches have provided a consistent result, implying that the in vitro activity of sPLA2-IIE may be physiologically relevant (at least in the skin).

In conclusion, our current studies have revealed non-redundant and unique roles of the two particular sPLA2s, IIE and IIF, in mouse skin. Although the epidermal expression of sPLA2-IIF is relevant to humans (19), we currently have no evidence that sPLA2-IIE is expressed in human skin. Instead, its closest homolog, sPLA2-IIA, is expressed in human skin (19) as well as in human adipose tissue (24). Presumably, in certain if not all situations, the functions of sPLA2-IIA in humans might be substituted by those of sPLA2-IIE in mice, in which sPLA2-IIA expression is limited to the intestine (e.g. BALB/c) or not expressed at all due to a frameshift mutation (e.g. C57BL/6) (42). This notion is supported by the fact that sPLA2-IIE is induced in several mouse tissues following lipopolysaccharide challenge (23), an event that has been well documented for sPLA2-IIA in humans with inflammation or endotoxin shock (43, 44). Alternatively, considering the hair follicle location of sPLA2-IIE in mice, the failure to detect sPLA2-IIE in human skin may simply be because the human body is not covered with fur. In this context, the spatiotemporal expression of sPLA2-IIE and other sPLA2s in healthy or diseased human skin would need careful evaluation in the context of epidermal proliferation, differentiation and activation, wound healing, inflammation, hair cycling, and aging. Given that millions of patients are suffering from chronic skin disorders, which can be caused by various factors, including genetic mutations, immunological abnormalities, hormonal imbalances, psychological stresses, or environmental exposures, full elucidation of the lipid networks regulated by sPLA2s would assist the search for novel treatments of skin diseases.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

All mice were housed in climate-controlled (23 °C) specific pathogen-free facilities with a 12-h light-dark cycle, with free access to standard laboratory food (CE2 Laboratory Diet, CLEA, Japan) and water. Pla2g2e−/− and Pla2g2f−/− mice, backcrossed to C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice (Japan SLC) for more than 12 generations, were described previously (19, 24). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science in accordance with the Japanese Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissues and cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems). PCRs were carried out using a Power SYBR Green PCR system (Applied Biosystems) or a TaqMan Gene Expression System (Applied Biosystems) on the ABI7300 Quantitative PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The probe/primer sets used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in quantitative RT-PCR

| Genes | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Probe no. (Roche Diagnostics) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actb | 5′-CTAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAG-3′ | 5′-ACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACA-3′ | 64 |

| Camp | 5′-GCCGCTGATTCTTTTGACAT-3′ | 5′-AATCTTCTCCCCACCTTTGC-3′ | 20 |

| Klk6 | 5′-CCTGTGCTTGGTTCTTGCTA-3′ | 5′-TCCATGAACCACCTTCTCCT-3′ | 64 |

| Krt1 | 5′-TTTGCCTCCTTCATCGACA-3′ | 5′-GTTTTGGGTCCGGGTTGT-3′ | 62 |

| Krt6a | 5′-AGTTTGCCTCCTTCATCGAC-3′ | 5′-TGCTCAAACATAGGCTCCAG-3′ | 84 |

| Krt6b | 5′-GGAAATTGCCACCTACAGGA-3′ | 5′-GGTGGACTGCACCACAGAG-3′ | 12 |

| Krt14 Krt14 | 5′-ATCGAGGACCTGAAGAGCAA-3′ | 5′-TCGATCTGCAGGAGGACATT-3′ | 83 |

| Krt15 | 5′-GGAAGAGATCCGGGACAAA-3′ | 5′-TGTCAATCTCCAGGACAACG-3′ | 71 |

| Krt16 | 5′-TGAGCTGACCCTGTCCAGA-3′ | 5′-CTCAAGGCAAGCATCTCCTC-3′ | 85 |

| Krt17 | 5′-GGAGCTGGCCTACCTGAAG-3′ | 5′-ACCTGGCCTCTCAGAGCAT-3′ | 63 |

| Krt33a | 5′-GGCCTACTTCAGGACCATTG-3′ | 5′-CGTTCTCAGATTTGCCACAC-3′ | 84 |

| Krt35 | 5′-TGCCCCGATTACCAGTCTTA-3′ | 5′-TGCCTTGCTGCAAAGAGTC-3′ | 25 |

| Krt75 | 5′-GGTCGACTCTCTGACTGACCA-3′ | 5′-ACCTGGTTCTGCATCTGAGAC-3′ | 13 |

| Krt83 | 5′-GAATTTGTGGCCCTGAAGAA-3′ | 5′-GCCTCCAGGTCTGACTTCC-3′ | 98 |

| Krt85 | 5′-CCAGGATGTGGAGTTACCAGA-3′ | 5′-GCCAGTTTTGGGGGCTAC-3′ | 15 |

| Pla2g2e | 5′-ACAGGGACAGAGCTTGCAGT-3′ | 5′-TTCATCCTGGGGGAGGTAG-3′ | 10 |

| Pla2g2f | 5′-GCTCTGGGCTGGAACTATGA-3′ | 5′-CCTGGGTTGCAGTTATACCG-3′ | 66 |

| Rn18s | 5′-TCGAGGCCCTGTAATTGGAA-3′ | 5′-CCCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTT-3′ | - |

| S100a9 | 5′-CACCCTGAGCAAGAAGGAAT-3′ | 5′-TGTCATTTATGAGGGCTTCATTT-3′ | 31 |

| TaqMan probe (Applied Biosystems) accession no. | |||

| Pla2g2e | Mm00478870_m1 | ||

| Pla2g2f | Mm00478872_m1 | ||

| Pla2g10 | Mm00449532_m1 | ||

| Gapdh | TaqMan Rodent GAPDH control reagents (4308313) | ||

Histological Analysis

Histological analysis was performed as described previously (19, 37). In brief, mouse tissues were fixed with 100 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, mounted on glass slides, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in ethanol with increasing concentrations of water. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on the 5-μm-thick cryosections. The stained sections were analyzed with a BX61 microscope (Olympus). Epidermal thickness was measured using DP2-BSW software (Olympus).

Microdissection

Mouse skin samples (P8) were embedded in OCT compound, sectioned (10-μm thick), mounted on DIRECTOR LMD slide (AMR Inc.), fixed with cold ethanol/acetic acid (19:1, v/v) for 5 min, and stained with toluidine blue. Laser-capture microdissection was performed on cryosections using Leica LMD6000 system (Leica). mRNA was extracted using RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen) from the isolated hair follicle or epidermis fraction.

In Situ Hybridization

Mouse Pla2g2e cDNA was subcloned into the pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega), and used for generation of sense and antisense RNA probes. Digoxigenin labeled-RNA probes were prepared with digoxigenin RNA labeling Mix (Roche Applied Science). Paraffin-embedded sections of mouse skin (6-μm thick) were hybridized with the digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes at 60 °C for 16 h (Genostaff). The bound label was detected using the alkaline phosphate color substrates 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyl phosphate p-toluidine and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride. The sections were counterstained with Kernechtrot (Muto Pure Chemicals).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Tissues were fixed with 100 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 1% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, post-fixed with 2% (w/v) OsO4 in PBS, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, passed through propylene oxide, and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 EPON (Polyscience). Ultrathin sections (0.08-μm thick) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and then examined using an electron microscope (H-7600; Hitachi).

IMQ-induced Psoriasis

Mice (BALB/c background, 8–12-week-old males) received a daily topical application of 12.5 mg of 5% (w/v) IMQ (Mochida Pharma) on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the ears over 4 days (total 50 mg of IMQ cream per mouse). Ear thickness was monitored at various time points with a micrometer, as described previously (19).

Hapten-induced Contact Dermatitis

On day −5, mice (C57BL/6 background, 8–12-week-old males) were sensitized with 50 μl of 0.5% (w/v) DNFB (Sigma) in acetone/olive oil (4/1; v/v) on the shaved abdominal skin (sensitization phase). On day 0, the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the ears were challenged with 20 μl of 0.3% DNFB (elicitation phase). Ear thickness was monitored with a micrometer, as described previously (19, 37).

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA extracted from skins was purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). The quality of RNA was assessed with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). cRNA targets were synthesized and hybridized with Whole Mouse Genome Microarray according to the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent Technologies). The array slides were scanned using a Laser Scanner GenePix 4000B (Molecular Devices) or a SureScan Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies). Microarray data were analyzed with GenePix software (Molecular Devices) or Agilent's Feature Extraction software. The GEO accession number for microarray is GSE80418.

TEWL

TEWL of mouse skin was determined using a Tewameter TM300 (Courage and Khazaka Electronic), as described previously (19).

Keratinocyte Culture

Keratinocytes were isolated from the whole skin of newborn mice using 0.05% (w/v) collagenase A (Roche Applied Science) in KGM(−) medium (MCDB 153 medium (Sigma) containing 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 14.1 μg/ml phosphorylethanolamine, 0.2% (v/v) Matrigel (BD Biosciences), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin) overnight at 4 °C. Then, the cells were cultured with KGM(+) medium (KGM(−) medium supplemented with 5 ng/ml insulin, 10 ng/ml EGF, and 40 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract). After 3 days, the cells were treated with 1 mm CaCl2 in KGM(+) medium. After appropriate periods, RNA was extracted from the cells and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR.

ESI-MS

Samples for ESI-MS of lipids were prepared and analyzed as described previously (19, 37). In brief, for detection of phospholipids, tissues were soaked in 10 volumes of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and then homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer. Lipids were extracted from the homogenates by the method of Bligh and Dyer (45). The analysis was performed using a 4000Q-TRAP quadrupole-linear ion trap hybrid mass spectrometer (AB Sciex) with liquid chromatography (NexeraX2 system; Shimazu). The samples were applied to a Kinetex C18 column (1 × 150-mm inner diameter, 1.7-μm particle) (Phenomenex) coupled for ESI-MS/MS. The samples injected by an autosampler (10 μl) were separated by a step gradient with mobile phase A (acetonitrile/methanol/water = 1:1:1 (v/v/v) containing 5 μm phosphoric acid and 1 mm ammonium formate) and mobile phase B (2-propanol containing 5 μm phosphoric acid and 1 mm ammonium formate) at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min at 50 °C. For detection of fatty acids and their oxygenated metabolites, tissues were soaked in 10 volumes of methanol and then homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer. After overnight incubation at −20 °C, water was added to the mixture to give a final methanol concentration of 10% (v/v). As an internal standard, 1 nmol of d5-labeled eicosapentaenoic acid and d4-labeled prostaglandin E2 (Cayman Chemicals) was added to each sample. The samples in 10% methanol were applied to Oasis HLB cartridges (Waters), washed with 10 ml of hexane, eluted with 3 ml of methyl formate, dried up under N2 gas, and dissolved in 60% methanol. The samples were then applied to a Kinetex C18 column (1 × 150-mm inner diameter, 1.7 μm particle) (Phenomenex) coupled for ESI-MS/MS as described above. The samples injected by an autosampler (10 μl) were separated using a step gradient with mobile phase C (water containing 0.1% acetic acid) and mobile phase D (acetonitrile/methanol = 4:1; v/v) at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min at 45 °C. Identification was conducted using multiple reaction monitoring transition and retention times, and quantification was performed based on peak area of the multiple reaction monitoring transition and the calibration curve obtained with an authentic standard for each compound, as described previously (19, 37).

PLA2 Enzyme Assay Using Skin-extracted Phospholipids

PLA2 assay was performed using skin-extracted phospholipids and pure recombinant human sPLA2s, as described previously (19). In brief, total phospholipids were extracted from mouse skin as above and further purified by straight-phase chromatography. The samples extracted in chloroform were applied to a Sep-Pak Silica Cartridge (Waters), washed sequentially with acetone and chloroform/methanol (9/1; v/v), eluted with chloroform/methanol (3/1; v/v), and dried under an N2 gas. The amounts of total phospholipids in samples were determined by the inorganic phosphorous assay (46). The membrane mimic composed of tissue-extracted lipids (1–10 μm) was sonicated for 5 min in 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 4 mm CaCl2 and then incubated for appropriate periods with 10 ng of recombinant sPLA2s (47) at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, the lipids were mixed with internal standards, extracted, and subjected to liquid chromatography-MS for detection of fatty acids and lysophospholipids, as noted above.

Statistical Analyses

All values are given as the means ± S.E. Differences between the two groups were assessed by unpaired Student's t test using the Excel Statistical Program File ystat 2008 (Igaku Tosho Shuppan, Tokyo, Japan). Differences at p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

M. M. and K. Y. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. Y. M., H. S., Y. N., and Y. T. performed several experiments. M. H. G. generated mutant mice and recombinant sPLA2 proteins. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We thank T. Fujino for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research 15H05905 and 16H02613 (to M. M.), 26461671 (to K. Y.), and 26860051 (to Y. M.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, the Terumo Foundation (to M. M.), and by AMED-CREST (to M. M.) and PRIME (to K. Y.) from the Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- SC

- stratum corneum

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

- eicosapentaenoic acid

- DNFB

- dinitrofluorobenzene

- ESI-MS

- electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- IMQ

- imiquimod

- IRS

- inner root sheath

- LA

- linoleic acid

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- LPC

- lysophosphatidylcholine

- LPE

- lysophosphatidylethanolamine

- P-LPE

- plasmalogen LPE

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- sPLA2

- secreted PLA2

- PUFA

- polyunsaturated fatty acid

- ORS

- outer root sheath

- TEWL

- transepidermal water loss.

References

- 1. Elias P. M., and Brown B. E. (1978) The mammalian cutaneous permeability barrier: defective barrier function is essential fatty acid deficiency correlates with abnormal intercellular lipid deposition. Lab. Invest. 39, 574–583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fuchs E. (2007) Scratching the surface of skin development. Nature 445, 834–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jobard F., Lefèvre C., Karaduman A., Blanchet-Bardon C., Emre S., Weissenbach J., Ozgüc M., Lathrop M., Prud'homme J. F., and Fischer J. (2002) Lipoxygenase-3 (ALOXE3) and 12R-lipoxygenase (ALOX12B) are mutated in non-bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (NCIE) linked to chromosome 17p13.1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grall A., Guaguère E., Planchais S., Grond S., Bourrat E., Hausser I., Hitte C., Le Gallo M., Derbois C., Kim G. J., Lagoutte L., Degorce-Rubiales F., Radner F. P., Thomas A., Küry S., et al. (2012) PNPLA1 mutations cause autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis in golden retriever dogs and humans. Nat. Genet. 44, 140–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vasireddy V., Uchida Y., Salem N. Jr., Kim S. Y., Mandal M. N., Reddy G. B., Bodepudi R., Alderson N. L., Brown J. C., Hama H., Dlugosz A., Elias P. M., Holleran W. M., and Ayyagari R. (2007) Loss of functional ELOVL4 depletes very long-chain fatty acids (> or =C28) and the unique ω-O-acylceramides in skin leading to neonatal death. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 471–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kazantseva A., Goltsov A., Zinchenko R., Grigorenko A. P., Abrukova A. V., Moliaka Y. K., Kirillov A. G., Guo Z., Lyle S., Ginter E. K., and Rogaev E. I. (2006) Human hair growth deficiency is linked to a genetic defect in the phospholipase gene LIPH. Science 314, 982–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Radner F. P., and Fischer J. (2014) The important role of epidermal triacylglycerol metabolism for maintenance of the skin permeability barrier function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elias P. M., Gruber R., Crumrine D., Menon G., Williams M. L., Wakefield J. S., Holleran W. M., and Uchida Y. (2014) Formation and functions of the corneocyte lipid envelope (CLE). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 314–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mao-Qiang M., Jain M., Feingold K. R., and Elias P. M. (1996) Secretory phospholipase A2 activity is required for permeability barrier homeostasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 106, 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fluhr J. W., Kao J., Jain M., Ahn S. K., Feingold K. R., and Elias P. M. (2001) Generation of free fatty acids from phospholipids regulates stratum corneum acidification and integrity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 117, 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fluhr J. W., Mao-Qiang M., Brown B. E., Hachem J. P., Moskowitz D. G., Demerjian M., Haftek M., Serre G., Crumrine D., Mauro T. M., Elias P. M., and Feingold K. R. (2004) Functional consequences of a neutral pH in neonatal rat stratum corneum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 123, 140–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nagamachi M., Sakata D., Kabashima K., Furuyashiki T., Murata T., Segi-Nishida E., Soontrapa K., Matsuoka T., Miyachi Y., and Narumiya S. (2007) Facilitation of Th1-mediated immune response by prostaglandin E receptor EP1. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2865–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Inoue A., Arima N., Ishiguro J., Prestwich G. D., Arai H., and Aoki J. (2011) LPA-producing enzyme PA-PLA1α regulates hair follicle development by modulating EGFR signalling. EMBO J. 30, 4248–4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uozumi N., Kume K., Nagase T., Nakatani N., Ishii S., Tashiro F., Komagata Y., Maki K., Ikuta K., Ouchi Y., Miyazaki J., and Shimizu T. (1997) Role of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in allergic response and parturition. Nature 390, 618–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leslie C. C. (1997) Properties and regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 16709–16712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mancuso D. J., Sims H. F., Yang K., Kiebish M. A., Su X., Jenkins C. M., Guan S., Moon S. H., Pietka T., Nassir F., Schappe T., Moore K., Han X., Abumrad N. A., and Gross R. W. (2010) Genetic ablation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ prevents obesity and insulin resistance during high fat feeding by mitochondrial uncoupling and increased adipocyte fatty acid oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36495–36510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shinzawa K., Sumi H., Ikawa M., Matsuoka Y., Okabe M., Sakoda S., and Tsujimoto Y. (2008) Neuroaxonal dystrophy caused by group VIA phospholipase A2 deficiency in mice: a model of human neurodegenerative disease. J. Neurosci. 28, 2212–2220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murakami M., Sato H., Miki Y., Yamamoto K., and Taketomi Y. (2015) A new era of secreted phospholipase A2. J. Lipid Res. 56, 1248–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamamoto K., Miki Y., Sato M., Taketomi Y., Nishito Y., Taya C., Muramatsu K., Ikeda K., Nakanishi H., Taguchi R., Kambe N., Kabashima K., Lambeau G., Gelb M. H., and Murakami M. (2015) The role of group IIF-secreted phospholipase A2 in epidermal homeostasis and hyperplasia. J. Exp. Med. 212, 1901–1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grass D. S., Felkner R. H., Chiang M. Y., Wallace R. E., Nevalainen T. J., Bennett C. F., and Swanson M. E. (1996) Expression of human group II PLA2 in transgenic mice results in epidermal hyperplasia in the absence of inflammatory infiltrate. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 2233–2241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamamoto K., Taketomi Y., Isogai Y., Miki Y., Sato H., Masuda S., Nishito Y., Morioka K., Ishimoto Y., Suzuki N., Yokota Y., Hanasaki K., Ishikawa Y., Ishii T., Kobayashi T., et al. (2011) Hair follicular expression and function of group X secreted phospholipase A2 in mouse skin. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11616–11631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valentin E., Ghomashchi F., Gelb M. H., Lazdunski M., and Lambeau G. (1999) On the diversity of secreted phospholipases A2. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31195–31202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suzuki N., Ishizaki J., Yokota Y., Higashino K., Ono T., Ikeda M., Fujii N., Kawamoto K., and Hanasaki K. (2000) Structures, enzymatic properties, and expression of novel human and mouse secretory phospholipase A2s. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5785–5793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato H., Taketomi Y., Ushida A., Isogai Y., Kojima T., Hirabayashi T., Miki Y., Yamamoto K., Nishito Y., Kobayashi T., Ikeda K., Taguchi R., Hara S., Ida S., Miyamoto Y., et al. (2014) The adipocyte-inducible secreted phospholipases PLA2G5 and PLA2G2E play distinct roles in obesity. Cell Metab. 20, 119–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schonthaler H. B., Guinea-Viniegra J., Wculek S. K., Ruppen I., Ximénez-Embún P., Guío-Carrión A., Navarro R., Hogg N., Ashman K., and Wagner E. F. (2013) S100A8-S100A9 protein complex mediates psoriasis by regulating the expression of complement factor C3. Immunity 39, 1171–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eckert R. L., Broome A. M., Ruse M., Robinson N., Ryan D., and Lee K. (2004) S100 proteins in the epidermis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 123, 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taylor K., Rolfe M., Reynolds N., Kilanowski F., Pathania U., Clarke D., Yang D., Oppenheim J., Samuel K., Howie S., Barran P., Macmillan D., Campopiano D., and Dorin J. (2009) Defensin-related peptide 1 (Defr1) is allelic to Defb8 and chemoattracts immature DC and CD4+ T cells independently of CCR6. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 1353–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Providence K. M., Higgins S. P., Mullen A., Battista A., Samarakoon R., Higgins C. E., Wilkins-Port C. E., and Higgins P. J. (2008) SERPINE1 (PAI-1) is deposited into keratinocyte migration “trails” and required for optimal monolayer wound repair. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 300, 303–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borgoño C. A., Michael I. P., Komatsu N., Jayakumar A., Kapadia R., Clayman G. L., Sotiropoulou G., and Diamandis E. P. (2007) A potential role for multiple tissue kallikrein serine proteases in epidermal desquamation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3640–3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Milora K. A., Fu H., Dubaz O., and Jensen L. E. (2015) Unprocessed interleukin-36α regulates psoriasis-like skin inflammation in cooperation with interleukin-1. J. Invest. Dermatol. 135, 2992–3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bernot K. M., Coulombe P. A., and McGowan K. M. (2002) Keratin 16 expression defines a subset of epithelial cells during skin morphogenesis and the hair cycle. J. Invest. Dermatol. 119, 1137–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mardaryev A. N., Ahmed M. I., Vlahov N. V., Fessing M. Y., Gill J. H., Sharov A. A., and Botchkareva N. V. (2010) Micro-RNA-31 controls hair cycle-associated changes in gene expression programs of the skin and hair follicle. FASEB J. 24, 3869–3881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen J., Jaeger K., Den Z., Koch P. J., Sundberg J. P., and Roop D. R. (2008) Mice expressing a mutant Krt75 (K6hf) allele develop hair and nail defects resembling pachyonychia congenita. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 270–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Krieg P., and Fürstenberger G. (2014) The role of lipoxygenases in epidermis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 390–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sato H., Isogai Y., Masuda S., Taketomi Y., Miki Y., Kamei D., Hara S., Kobayashi T., Ishikawa Y., Ishii T., Ikeda K., Taguchi R., Ishimoto Y., Suzuki N., Yokota Y., et al. (2011) Physiological roles of group X-secreted phospholipase A2 in reproduction, gastrointestinal phospholipid digestion, and neuronal function. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11632–11648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murase R., Sato H., Yamamoto K., Ushida A., Nishito Y., Ikeda K., Kobayashi T., Yamamoto T., Taketomi Y., and Murakami M. (2016) Group X secreted phospholipase A2 releases ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, suppresses colitis, and promotes sperm fertility. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6895–6911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miki Y., Yamamoto K., Taketomi Y., Sato H., Shimo K., Kobayashi T., Ishikawa Y., Ishii T., Nakanishi H., Ikeda K., Taguchi R., Kabashima K., Arita M., Arai H., Lambeau G., et al. (2013) Lymphoid tissue phospholipase A2 group IID resolves contact hypersensitivity by driving antiinflammatory lipid mediators. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1217–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garza L. A., Liu Y., Yang Z., Alagesan B., Lawson J. A., Norberg S. M., Loy D. E., Zhao T., Blatt H. B., Stanton D. C., Carrasco L., Ahluwalia G., Fischer S. M., FitzGerald G. A., and Cotsarelis G. (2012) Prostaglandin D2 inhibits hair growth and is elevated in bald scalp of men with androgenetic alopecia. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 126ra134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nelson A. M., Loy D. E., Lawson J. A., Katseff A. S., Fitzgerald G. A., and Garza L. A. (2013) Prostaglandin D2 inhibits wound-induced hair follicle neogenesis through the receptor, Gpr44. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 881–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sasaki S., Hozumi Y., and Kondo S. (2005) Influence of prostaglandin F2α and its analogues on hair regrowth and follicular melanogenesis in a murine model. Exp. Dermatol. 14, 323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Neufang G., Furstenberger G., Heidt M., Marks F., and Müller-Decker K. (2001) Abnormal differentiation of epidermis in transgenic mice constitutively expressing cyclooxygenase-2 in skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7629–7634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. MacPhee M., Chepenik K. P., Liddell R. A., Nelson K. K., Siracusa L. D., and Buchberg A. M. (1995) The secretory phospholipase A2 gene is a candidate for the Mom1 locus, a major modifier of ApcMin-induced intestinal neoplasia. Cell 81, 957–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pruzanski W., and Vadas P. (1991) Phospholipase A2–a mediator between proximal and distal effectors of inflammation. Immunol. Today 12, 143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Murakami M., Taketomi Y., Miki Y., Sato H., Hirabayashi T., and Yamamoto K. (2011) Recent progress in phospholipase A2 research: from cells to animals to humans. Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 152–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bligh E. G., and Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eaton B. R., and Dennis E. A. (1976) Analysis of phospholipase C (Bacillus cereus) action toward mixed micelles of phospholipid and surfactant. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 176, 604–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Degousee N., Ghomashchi F., Stefanski E., Singer A., Smart B. P., Borregaard N., Reithmeier R., Lindsay T. F., Lichtenberger C., Reinisch W., Lambeau G., Arm J., Tischfield J., Gelb M. H., and Rubin B. B. (2002) Groups IV, V, and X phospholipases A2s in human neutrophils: role in eicosanoid production and gram-negative bacterial phospholipid hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5061–5073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Miki Y., Kidoguchi Y., Sato M., Taketomi Y., Taya C., Muramatsu K., Gelb M. H., Yamamoto K., and Murakami M. (May 21, 2016) Dual roles of group IID phospholipase A2 in inflammation and cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 291, M116.734624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]