Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV) is a prototypical emerging virus for which no effective therapeutics currently exist. WNV uses programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting (−1 PRF) to synthesize the NS1′ protein, a C terminally extended version of its non-structural protein 1, the expression of which enhances neuro-invasiveness and viral RNA abundance. Here, the NS1′ frameshift signals derived from four WNV strains were investigated to better understand −1 PRF in this quasispecies. Sequences previously predicted to promote −1 PRF strongly promote this activity, but frameshifting was significantly more efficient upon inclusion of additional 3′ sequence information. The observation of different rates of −1 PRF, and by inference differences in the expression of NS1′, may account for the greater degrees of pathogenesis associated with specific WNV strains. Chemical modification and mutational analyses of the longer and shorter forms of the −1 PRF signals suggests dynamic structural rearrangements between tandem stem-loop and mRNA pseudoknot structures in two of the strains. A model is suggested in which this is employed as a molecular switch to fine tune the relative expression of structural to non-structural proteins during different phases of the viral replication cycle.

Keywords: flavivirus, gene regulation, molecular genetics, plus-stranded RNA virus, ribosome, RNA structure, translation control, programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting, West Nile virus, pseudoknot

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV)4 is a member of the Japanese encephalitis serogroup within the genus Flaviviridae (1). WNV is an enveloped virus that contains a single-stranded plus-strand RNA genome that harbors one open reading frame encoding three structural and seven non-structural (NS) proteins (Fig. 1A). WNV is named for the region in Uganda where it was first isolated in 1937 (1). It is a zoonosis, i.e. it replicates and accumulates in birds and spreads to new hosts via mosquitoes (1). The virus has been known to infect other animals including cows, horses, and humans. Humans are considered to be “dead end hosts” as the virus is not able to accumulate to high enough titers to enable person-to-person transmission. WNV infection produces symptoms ranging from mild fever to paralysis (2). There are numerous variations, or “strains” of West Nile virus that are generally classified into two distinct lineages (3). Lineage 1 strains are found throughout the world in Africa, Australia, South America, North America, and the Middle East and include those most commonly associated with severe human illnesses, i.e. meningoencephalitis (encompassing encephalitis, meningitis, myelitis, and cases with overlapping features of these syndromes). Lineage 2 strains are limited to the African continent and typically cause the clinically uncomplicated West Nile fever in humans, which typically lasts less than a week (1). WNV was introduced into the United States in 1999, causing a meningoencephalitis outbreak in New York City resulting in 7 deaths (2). In 2002, there were nearly 4000 human cases of WNV-associated disease reported with 246 deaths (4). In addition, more than 14,000 dead crows, blue jays, and other birds were found to be infected. The virus has been documented in all 48 states and the District of Columbia in the United States mainland, sparking nationwide interest in finding ways to prevent and treat the resulting illnesses. No WNV vaccine has been approved for human use (5) leaving current prevention efforts focused entirely on mosquito control (6). Treatment of WNV-related diseases is primarily palliative (5). Some antivirals show potential, but none have been proven effective in humans (6). Thus, there is a demand for a drug effective for treatment of WNV infection. When considering drug development, it is important to identify molecular mechanisms that are specific to the pathogen.

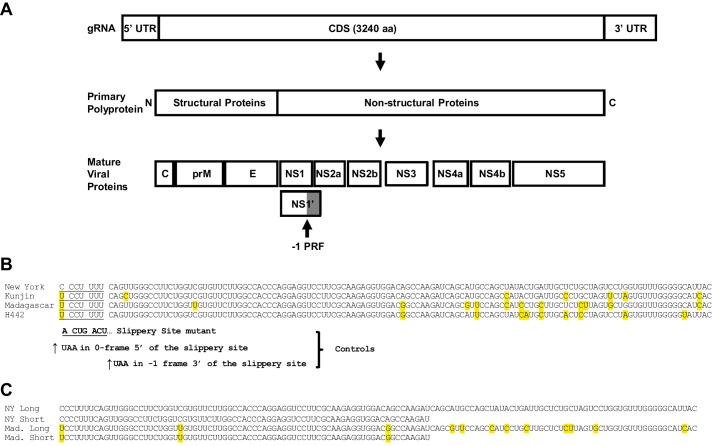

FIGURE 1.

A, maps of the West Nile virus genomic RNA (top), primary polyprotein (middle), and mature viral proteins (bottom). The approximate location of the −1 PRF signal in the NS1 protein, and the NS1′ protein are indicated. B, sequences of long forms of the −1 PRF signals derived from the four strains of West Nile virus were examined in this study. The heptameric slippery sites are underlined, and the incoming 0-frame codons are indicated by spaces. Single nucleotide differences among these sequences are highlighted in yellow, using the New York strain as the baseline reference. Mutants examined in this study are indicated below. All slippery site mutants (No-slip) contained the sequence UCGUACU. In the Stop-ss mutants, an in-frame UAA codon was placed immediately 5′ of the slippery site. In the Slippery site-stop mutants (ss-stop) a UAA codon was placed in the −1 frame immediately 3′ of the slippery site. C, Long and Short sequences were derived from the New York and Madagascar WNV strains used in this study.

Many viruses, particularly those with RNA genomes such as WNV, utilize a molecular mechanism called programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting (−1 PRF) to make more efficient use of their small genomes: −1 PRF enables them to control the relative expression of different proteins encoded within a single open reading frame. Programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifts direct a fraction of translating ribosomes to shift one base in the 5′ direction, enabling them to continue translation in the −1 reading frame (7). Frameshift signals typically comprise three parts: a slippery site, a spacer, and an mRNA structural element, often an mRNA pseudoknot (7). A slippery site is a heptameric sequence on which frameshifting can occur while maintaining non-wobble base pairing between tRNAs in the ribosomal A- and P-sites with the mRNA after the frameshift event. The spacer is a short region between the slippery site and the downstream structural element. This structural element is thought to direct the ribosome to stall with its A- and P-site tRNAs positioned over the slippery site, which increases the likelihood of kinetic partitioning of ribosomes into the −1 frame (8, 9). It is not known whether the mRNA structural element plays an active role in this process, or if it is a passive participant. Prior studies using the Kunjin variant of WNV demonstrated that the virus utilizes −1 PRF to produce an extended version of the NS1 protein, called NS1′ (10). Whereas NS1 plays an essential role in viral replication and assembly, NS1′ is not essential. However, in addition to serving the same function as NS1, it has effects on WNV virulence: abrogation of NS1′ production reduces neuroinvasiveness (10), viral replication, and RNA levels (11, 12). The primary translational product is a polyprotein that is subsequently cleaved into structural (encoded by sequences in the 5′ region of the genome) and NS (encoded downstream sequence) proteins (Fig. 1A). Programmed −1 ribosomal frameshift events direct translating ribosomes to an out-of-frame stop codon. Thus, the −1 PRF signal is localized in the WNV genome such that frameshift events prevent production of NS proteins, i.e. −1 PRF affects ratios of structural (upstream of the frameshift) to non-structural (downstream). Increased frameshifting results in production of more structural proteins favoring virion production. Indeed, inhibition of frameshifting resulted in decreased ratios of structural/non-structural proteins (E/NS5 ratio), and in decreased virus production (11). Furthermore, −1 PRF attenuated mutants showed reduced virulence in a mouse encephalitis model (10). The infectivity of a −1 PRF-deficient WNV-NY infectious clone was also attenuated in birds, and a −1 PRF-deficient WNV-Kunjin virus displayed decreased replication and spread in Culex mosquitos (11). Thus, −1 PRF presents a possible therapeutic target against WNV.

Although the WNV −1 PRF signal was previously identified, detailed functional and structural analyses have not been undertaken. To address this, the NS1′ frameshift signals of four WNV strains were analyzed. The study included two lineage 1 strains (New York and Kunjin) and two from lineage 2 (Madagascar and h442). The New York strain (accession number NC_009942) was responsible for the 1999 encephalitis outbreak in New York and continues to be one of the main virulent strains in the United States (2). Kunjin (accession number AY274504) has caused outbreaks of disease in human and equine populations in Australia. It was previously believed to be a unique species, but now occupies its own clade within lineage 1 of WNV (12). The Madagascar strain (accession number DQ176636) caused an outbreak of disease in birds in 1978, but does not produce appreciable pathogenesis in humans (13). The h442 strain (accession number EF429200) was isolated from a patient in South Africa and is one of the few lineage 2 strains associated with human disease (14). Consistent with prior studies using mammalian and mosquito cells as well as cell-free assays (10, 15), measurements using standard dual-luciferase reporters in HeLa cells revealed that the sequences from all four strains promote very high rates of −1 PRF: from ∼30 to ∼70%. Mutational analyses are consistent with −1 PRF, and do not support the presence of cryptic promoters or internal ribosome entry site elements. This approach also revealed the requirement of additional sequences 3′ of those previously identified for optimal frameshifting activity. Notably, rates of −1 PRF promoted by the pathogenic strain sequences were significantly greater than those conferred by sequences derived from the low pathogenesis Madagascar strain. Much of the difference in −1 PRF efficiencies between the New York (pathogenic) and Madagascar strains can be attributed to a single base difference in their heptameric slippery sequences. In addition, chemical modification studies suggest that, at least in these two cases, the −1 PRF promoting elements may be structurally dynamic, transiting between tandem stem-loop and mRNA pseudoknot structures, such that formation of pseudoknot structures further enhance the already strong −1 PRF stimulating activity of slippery site proximal stem loops. The deeper understanding of the structural and molecular biology of the WNV −1 PRF signals may partially explain the increased pathogenicity of the New York strain of WNV that can be exploited for therapeutic intervention.

Results

The WNV Sequences Encode Bona Fide −1 PRF Signals

The predicted −1 PRF signal sequences identified in the Recode Database (16) are limited to 75 nucleotides in length, and secondary structures are predicted using mfold (17), a program that cannot predict complex RNA structures such as pseudoknots.

Given that many known viral −1 PRF signals are longer than 75 nucleotides and are comprised of mRNA pseudoknots, longer sequence windows (up to 129 nucleotides) were analyzed by three programs capable of identifying pseudoknotted RNAs: Pknots (18), NUPACK (19), and HotKnots (20). These suggested that additional 3′ sequence information may participate in the downstream −1 PRF stimulatory structures (not shown). Thus, the 129-nucleotide long sequences shown in Fig. 1B derived from the New York, Kunjin, Madagascar, and h442 strains were cloned into the dual luciferase vector p2luci (21). This figure also highlights the presence of heterogeneity among these sequences, most of which maps to sequence 3′ of the original 75-nucleotide window. However, it is notable that the first triplet of the WNV-NY slippery site is a perfect CCC, whereas this is UCC in the other three strains. The full-length sequences shown in Fig. 1B were cloned into dual luciferase reporters, as well as three additional series of mutant versions of the frameshift signals that were created as controls. Mutation of the (T/C)CCTTTT (0-frame indicated by spaces) slippery sites to ACTGACT were constructed to validate −1 PRF through the canonical mechanism. Constructs harboring termination codons in the zero frame 5′ of the slippery sites were used to control for the presence of cryptic promoters, whereas those harboring termination codons in the −1 frame 3′ of the slippery sites were used to control for the presence of internal ribosome entry site elements or cryptic splice sites (Fig. 1B). All four of the longer WNV-derived sequences promoted highly efficient frameshifting, ranging from ∼35% (Madagascar) to ∼72% (Kunjin) (Fig. 2A). In all cases, the mutated frameshift signals showed a near complete loss of firefly luciferase expression. These findings provide strong genetic support for the hypothesis that the WNV-derived sequences direct highly efficient levels of −1 PRF.

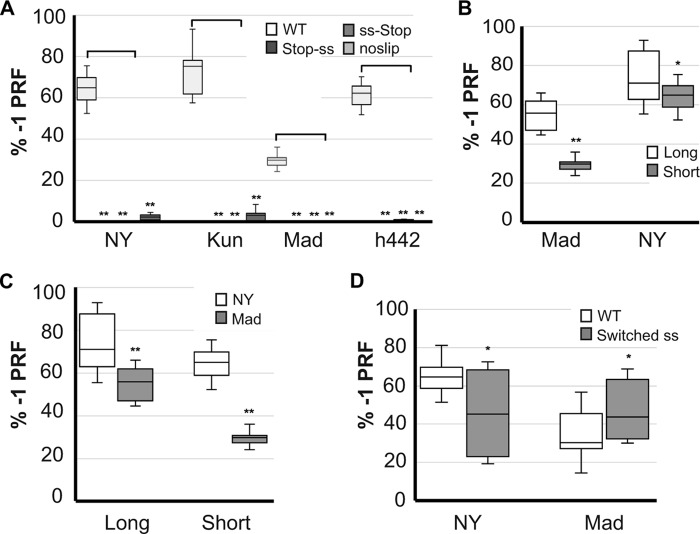

FIGURE 2.

A, frameshifting efficiencies of each of the long sequences and three mutants shown in Fig. 1B were monitored by dual luciferase assay (21, 35) and statistically analyzed as previously described (36). Data are presented as percentage of a read-through control (% −1PRF). At least three technical replicates were performed on multiple biological replicates for each experiment. The number of biological replicates for each sample are as follows. New York WT, 11; NY Stop-ss, ss-Stop, and noslip controls, 3. Kunjin WT, 7; Kunjin Stop-ss, 8; Kunjin ss-Stop, 4; Kunjin no-slip, 8. Madagascar WT, 6. Mad Stop-ss, ss-Stop, and noslip, 3 each. H422 WT, 5; H422 Stop-ss, ss-Stop, and noslip, 4 each. B and C, comparison of −1 PRF efficiencies promoted by the long and short versions of the New York and Madagascar WNV sequences. In B, data are presented as intra-strain comparisons, whereas the analysis in panel C makes inter-strain comparisons. For all experiments, at least three biological replicates were performed in triplicate. D, effects of switching the first bases of the New York and Madagascar slippery sites into their respective downstream sequences. For all experiments, four biological replicates were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (unpaired two-sample t test).

A prior report suggested that the WNV −1PRF signals were entirely encoded within shorter 75-nucleotide long sequences (15) (Fig. 1C). To determine whether an additional sequence is required to promote optimal frameshifting, the −1 PRF activities of the shorter sequences (NY Short and Madagascar Short) were compared with those of the longer sequences (NY Long and Madagascar Long) using the dual luciferase assay. Although both of the short sequences were able to promote efficient levels of −1 PRF, the actual values were significantly less than those promoted by their longer counterparts indicating that the complete WNV −1 PRF signals extend beyond the previously predicted 75 nucleotides (Fig. 2B). Additionally, a head to head comparison of the New York versus Madagascar −1 PRF signals revealed both the short and long versions of the New York-derived sequence promoted statistically significant greater levels of frameshifting than those derived from the Madagascar strain (Fig. 2C).

As noted above, the New York strain CCCUUUU slippery site conforms to the canonical XXXYYYZ slippery site (22). In contrast, the Madagascar UCCUUUU slippery site is non-canonical, although it does allow for G-U base pairing between the P-site tRNA and the −1 frame codon upon slippage (23, 24). To determine whether this single base difference may partially account for the observed increased ability of the New York WNV-derived sequence to promote −1 PRF relative to the Madagascar strain, the slippery sites were switched between the two in the context of the full-length signal. Consistent with this hypothesis, swapping the UCCUUUU slippery site into the New York WNV sequence resulted in a significant decrease in the efficiency of −1 PRF promoted by this sequence (Fig. 2D). Conversely, substitution of the CCCUUUU slippery site into the Madagascar WNV sequence promoted significantly increased rates of −1 PRF relative to the wild-type frameshift signal (Fig. 2D).

Chemical Modification Analyses Suggest That the WNV −1 PRF Signals Are Structurally Complex, Diverse, and Dynamic

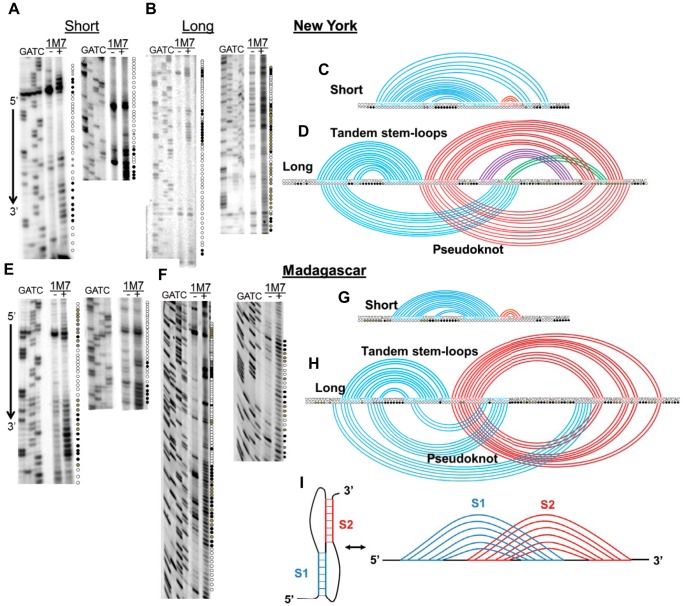

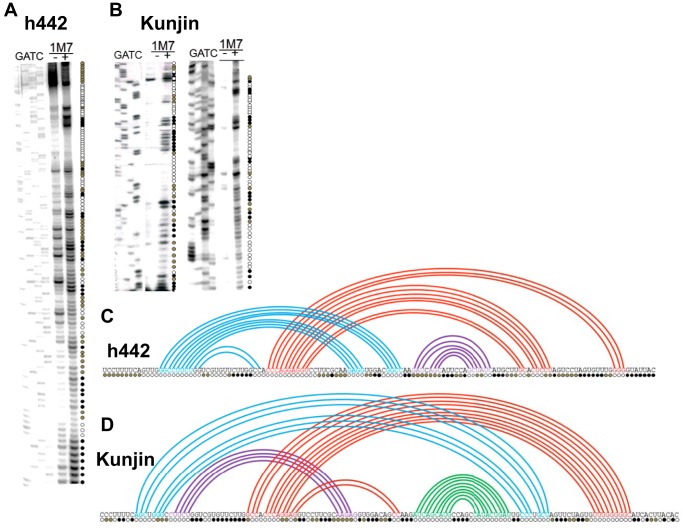

The combination of (a) sequence diversity among the different WNV −1 PRF signals, (b) the observed range of −1 PRF promoted by these sequences, and (c) the observed differences in −1 PRF activities between the long and short forms of the New York and Madagascar WNV −1 PRF signals suggested a certain degree of structural complexity among these frameshift stimulating sequences. To investigate this further, synthetic “short” and “long” form RNA transcripts of the New York and Madagascar strains of the WNV −1 PRF signals were treated with 1M7, and subjected to SHAPE analyses. Representative autoradiograms are shown in Fig. 3, A (the short New York WNV sequence, i.e. New York Short), B (New York Long), E (Madagascar Short), and F (Madagascar Long). Autoradiograms of denaturing polyacrylamide gels were scored for reactivity of 1M7 versus untreated (DMSO only) control RNAs. SHAPE data were combined with computational predictions to create two-dimensional models of the folded structures. For ease of visualization, these are depicted as Feynman diagrams (18). These analyses indicated that the short forms of both −1 PRF signals form similar stem-loop structures (Fig. 3, C and G). In contrast, the long versions of the WNV New York and Madagascar −1 PRF signals appeared to be able to assume at least two distinct and mutually exclusive structures: tandem stem-loops and more complex mRNA pseudoknots, each of which span nearly the entire 129-nucleotide sequences (Fig. 3, D and H). The different 3′ sequences among all four strains also suggested that there may be a significant amount of structural diversity among the various −1 PRF signals. To address this, SHAPE analysis was also performed on the long versions of −1 PRF signals derived from the Kunjin and h442 strains. This analysis revealed that they, too, were able to form complex RNA pseudoknot structures encompassing nearly the entire length of the sequences (Fig. 4, A–D). Consistent with the hypothesis, this analysis revealed significant structural diversity in the −1 PRF signals of the four strains.

FIGURE 3.

Structural analyses of the short and long versions of the WNV New York and Madagascar −1 PRF signals. Panels A, B, D, and F depict representative autoradiograms of SHAPE reactions for each sample. Each autoradiogram includes sequencing lanes, control (−), and test (+) lanes. Circles denote the extent of chemical modification by 1M7 where open circles are unmodified, gray indicates partially modified, and black are strongly modified. Panels C, D, G, and H show base pairing pattern solutions derived from the chemical modification data as Feynman diagrams (18). The slippery sites are contained in the first seven bases of each of the linear sequences. Colors denote different stem-loop groups. In the long sequence versions, the tandem stem-loop solutions are drawn above the linear sequences, and the RNA pseudoknot solutions are drawn below the linear sequences. (Note the presence of a possible pseudoknot above the line in Fig. 3D as the intersection between the purple and green arcs.) Panel I shows two schematic representations of an RNA pseudoknot structure. At left is the traditional flat representation, which can be converted to the Feynman diagram shown at right. Colored arcs link base pairs, and each stem is represented by a unique color. Pseudoknotted structures can be visually identified in Feynman diagrams by overlaps between different colored arcs.

FIGURE 4.

Structural analyses of the long versions of the WNV h442 (panels A and C) and Kunjin (panels B and D) −1 PRF signals. Annotations are the same as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

Discussion

Consistent with prior studies (10, 15), a thorough genetic analysis strongly supports the hypothesis that these sequences promote highly efficient rates of −1 PRF. However, whereas those studies employed the computationally predicted 75-nucleotide long WNV stem-loop structure, the current analysis revealed that an additional 3′ sequence (∼50 nucleotides) contributes to enhancement of −1 PRF efficiency. Although the shorter sequences promote very high levels of −1 PRF (compare the 30–50% promoted by these WNV sequences to the ∼1–15% observed for the −1 PRF signals of most other viruses (25)), the longer sequences further serve to increase −1 PRF rates. This is likely because mRNA pseudoknots are more difficult for ribosomes to resolve than the stem-loops observed in shorter sequences, resulting in longer ribosomal stalling thus increasing the chances for −1 PRF to occur. Furthermore, −1 PRF promoted by sequences derived from pathogenic strains was consistently more efficient than those promoted by the non-pathogenic Madagascar strain. Swapping the slippery sites of the New York and Madagascar strains revealed that this can be partially attributed to a single base difference. However, it should be noted that both the Kunjin and h442 strains also harbor the UCCUUUU slippery sites, and thus this is not the sole reason for lower rates of −1 PRF by the Madagascar WNV-derived sequence. As discussed above, this increased efficiency should result in higher expression of NS1′, increasing the ratios of structural to non-structural viral proteins enabling greater production of WNV virions by the New York strain. Thus, this single base difference may partially account for the increased pathogenicity of this strain.

SHAPE analyses revealed a greater degree of RNA structural variation than was previously predicted among the −1 PRF promoting mRNA pseudoknots of the WNV-NY and WNV-Madagascar strains. This is likely due to the greater number of sequence differences toward the 3′ ends of the signals, which were not included in earlier computational predictions, demonstrating the need for empirical wet-bench studies to complement computational predictions. The high degree of sequence (Fig. 1) diversity among the −1 PRF signals from the different WNV strains is consistent with the prior observations that cis-acting elements such as −1 PRF signals evolve rapidly (26–29). Furthermore, their structural diversity (Figs. 3 and 4) suggests that −1 PRF signals are very plastic, i.e. that highly efficient levels of −1 PRF can be easily stimulated by many different RNA structures. Analyses of the long forms of the New York and Madagascar −1 PRF stimulatory sequences also support this idea of structural dynamism: both tandem stem-loop and mRNA pseudoknot structures can be derived from the SHAPE data (Fig. 3). Given the functional analyses showing that the entirety of these sequences are required for maximal frameshifting (Fig. 2), we suggest that the tandem stem-loops first may be formed co-transcriptionally, and that the more complex structure is folded post-transcriptionally. Co-transcriptional formation of the tandem stem-loops seems likely because the first loop could form in its entirety before transcription of the 3′ end of the signal has been completed. This is also consistent with the structure formed by the shorter sequences, showing the absence of the 3′ end still permits formation of the 5′ proximal stem-loop (Fig. 3). After transcription is complete, however, longer range base pairing interactions can enable the RNA to refold into the mRNA pseudoknot structures. This RNA folding is a dynamic process; the same sequence may have different conformations temporally and/or spatially. Indeed, it is possible that this structural heterogeneity could function as a molecular switch to control viral structural to non-structural protein production through the infectious program. For example, during the early phase of infection it may be advantageous for the virus to maximize production of non-structural proteins; this may be required to delay onset of the innate immune response (13, 30–32). This could be effected by decreasing −1 PRF by favoring formation of the stem-loop structures. In contrast, during the late phase of infection, maximization of −1 PRF by favoring formation of the pseudoknotted structures would serve to increase synthesis of structural proteins, maximizing viral particle production. Alternative to the dynamic switch model, this sequence element may simply function like a resistor, attenuating the amplitude of the downstream translational output to control the relative ratios of structural to non-structural proteins independent of the viral lifecycle. Regardless of the switch or resistor model, increased production of virions consequent to higher levels of −1 PRF may contribute to viral pathogenesis as discussed above. It should be noted that WNV can be viewed as a prototype for emerging Flaviviruses in the Western hemisphere, including the Zika virus. In addition, emerging Alphaviruses, e.g. Chikungunya, and the Equine Encephalitis viruses also utilize −1 PRF (16). A deeper understanding of how RNA structural dynamics control −1 PRF and gene expression and how this may relate to the viral life cycle may contribute toward understanding how to disrupt the process.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Genetics and Cell Culture

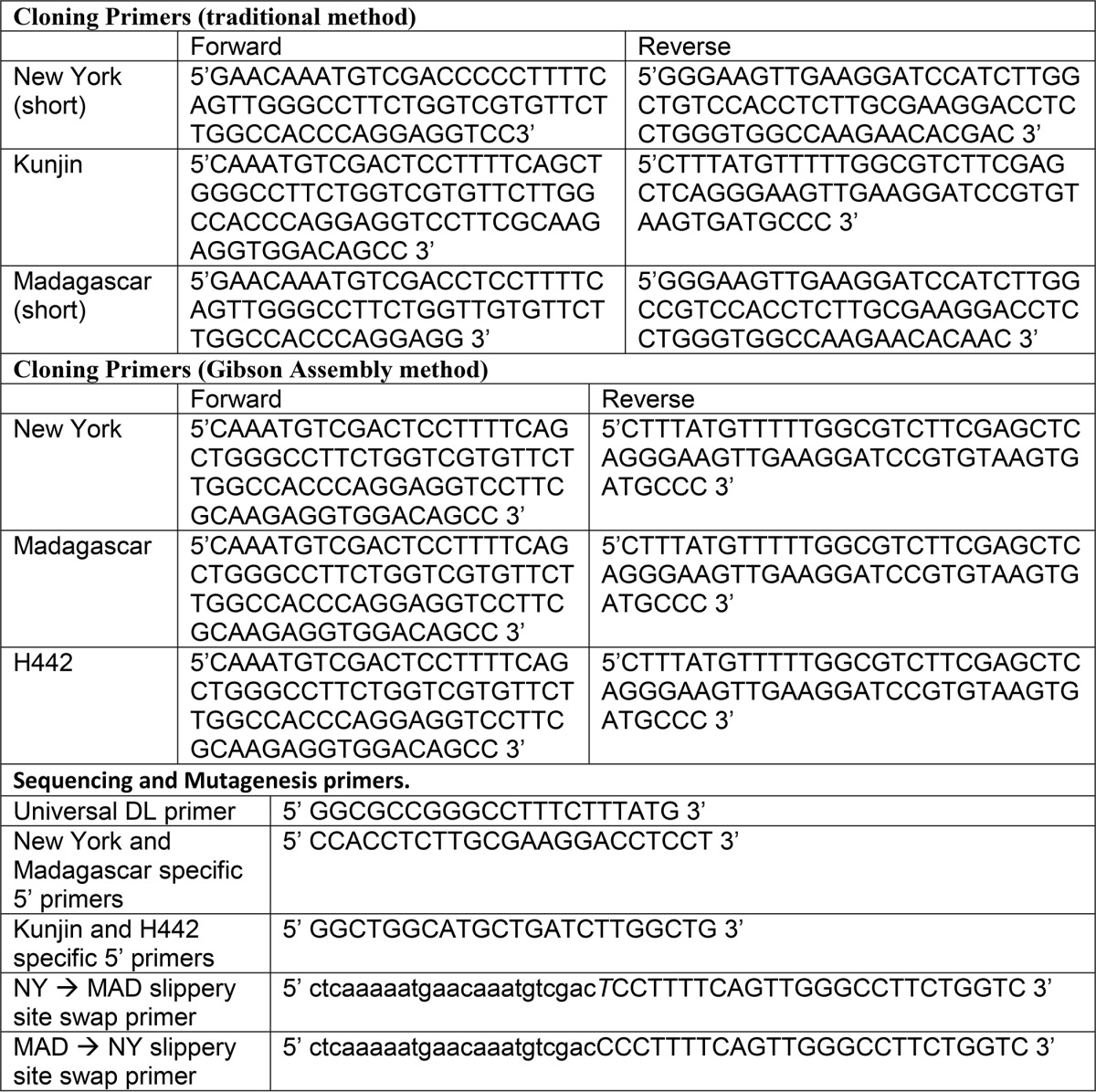

Predicted WNV −1 PRF sequences were identified in the Recode Database (33). These are shown in Fig. 1B. Kunjin and shortened versions of the New York and Madagascar WNV-derived sequences were cloned using classic molecular biology methods, i.e. restriction digest followed by ligation. For this method, synthetic forward and reverse primers containing overlaps of at least 20 nucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies) were designed to include BamHI and SalI restriction endonuclease recognition sites (Table 1). Primers were extended and amplified from full-length clones (kindly provided by Dr. Brenda Fredericksen) by PCR using the DreamTaq Master Mix (Life Technologies), using the following protocol: denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 40 s over the course of 30 cycles. Insert size and purity were confirmed by electrophoresis through 1% TAE-agarose gel and extracted using the GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Fermentas). BamHI/SalI-digested inserts were ligated into a similarly cut dual luciferase reporter plasmid p2luci (21) with T4 DNA ligase such that only a −1 shift in the reading frame would result in translation of the downstream firefly luciferase gene. All other sequences were cloned into p2luci using the Gibson Assembly method (34). Primers were designed with at least 15 nucleotide overlaps with both each other and the template and ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (Table 1). Primers were extended and amplified via PCR, gel purified, and extracted as described above. Linear plasmid and inserts were assembled using Gibson Assembly master mix (New England BioLabs) at 50 °C for 1 h. All plasmids were amplified in Escherichia coli strain DH5α and extracted using GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Life Technologies). Cloned sequences were confirmed by commercial sequence analysis (GeneWiz). Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was used to create additional reporters harboring the following (see Fig. 1A): (a) a 0-frame UAA termination codon immediately 5′ of the WNV slippery sites to control for the presence of cryptic promoters; (b) a UAA termination codon in the −1 frame immediately after the slippery site to control for the presence of internal ribosome entry site elements; and (c) substitution of the non-slippery ACTGACT sequence for the wild-type slippery sequences to verify that slippage was dependent on the slippery sequences. Primers used for sequence confirmation and to construct reciprocal swaps of the New York and Madagascar WNV slippery sites into one another's downstream frameshift promoting sequences are shown in Table 1. HeLa cells (ATCC) were grown at 37 °C in DMEM+++ (7.5 ml of fetal bovine serum, 100 μl of penicillin and streptomycin, 500 μl of non-essential amino acid mixture, 1 ml of 5% l-glutamate, 41 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) and 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with 1100 ng of plasmid and 3.3 μl of FuGene reagent in 1 ml of DMEM+++ and grown overnight in 12-well plates.

TABLE 1.

Oligonnucleotide primers used in this study

Dual Luciferase Assays

Frameshifting efficiencies were tested by dual luciferase assay (21, 35). Forty hours post-transfection, Renilla and Firefly luciferase activities were measured in HeLa cell lysates using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System and read with a GloMax®-Multi Microplate Luminometer (Promega). p2luci was employed as the in-frame control. Lysates of mock-transfected HeLa cells were used to control for background levels of luminescence. −1 PRF efficiencies were calculated as the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase reads and statistical analyses were performed as previously described (36).

Selective 2′-Hydroxyl Acylation Analyzed by Primer Extension

RNA transcripts of frameshift signals were synthesized using the MEGAscript T7 kit (Ambion) at 37 °C overnight and purified using the MEGAclear kit (Ambion). Full-length transcripts were purified from 1% agarose gels. Transcripts were treated with 1-methyl-7-nitroisatoic anhydride (1M7) using 10 pmol of RNA, folding buffer, and 1M7 at 37 °C for 10 min. Identical reactions were performed with DMSO as a negative control. SHAPE primers (IDT) were designed to amplify the transcripts from two points to allow for resolution of the entire frameshift signal. A universal primer was designed to anneal to the Renilla sequence 3′ of the frameshift sequence, optimizing visualization of the 3′ end of the sequence. Specific primers were designed to anneal to the middle of individual viral sequences to enable optimal resolution of the 5′ ends of the viral sequences. Primers were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 DNA kinase at 37 °C for 30 min. Labeled primers were purified using Sephadex 25 spin columns. 1M7- and DMSO-treated RNAs were denatured at 65 °C for 5 min, and annealed with RNAs at 42 °C for 15 min. An enzyme mixture containing dNTPs, DTT, SuperScript III (Life Technologies), and buffer was added to the primed RNA. cDNA synthesis proceeded at 45 °C for 10 min followed by 52 °C for 10 min.

Denaturing Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis and Interpretation

Synthesized cDNAs and parallel sequencing reactions were separated through 8% polyacrylamide urea denaturing gels. Radiolabeled cDNAs were visualized using a Typhoon phosphorimager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Phosphorimages were scored by identifying bands appearing in the 1M7-treated, but not the DMSO control lanes. Dark bands were scored as strongly reactive, lighter, 1M7-specific bands were scored as moderately reactive, and the appearance of no band was scored as unreactive. After scoring, secondary structures were manually refined using computationally predicted folding structures as guides (18–20).

Author Contributions

C. M. and J. D. D. designed the project and experiments. C. M. produced the data presented in Figs. 2, A–C, 3, and 4. S. M. contributed to Figs. 3 and 4. Y. K. and J. E. J. designed, produced, and generated the data presented in Fig. 2D. Y. K. designed Fig. 2. All authors participated in analyzing the data. J. D. D. wrote the manuscript, and all authors participated in the editing process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brenda Fredericksen for providing us starting materials and helping with primer design and synthesis of WNV-derived sequences. We also thank members of the Dinman lab past and present, with special thanks to Drs. Alicia Cheek, Suna Gulay Tatiana Watanabe, and Mary Mirvis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01HL119439 and R01GM117177 (to J. D. D.) and Defense Threat Reduction Agency Grant HDTRA1-13-1-0005. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the federal government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- WNV

- West Nile virus

- NS

- non-structural

- −1 PRF

- programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting

- 1M7

- 1-methyl-7-nitroisatoic anhydride

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide.

References

- 1. Campbell G. L., Marfin A. A., Lanciotti R. S., and Gubler D. J. (2002) West Nile virus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petersen L. R., Marfin A. A., and Gubler D. J. (2003) West Nile virus. JAMA 290, 524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lanciotti R. S., Ebel G. D., Deubel V., Kerst A. J., Murri S., Meyer R., Bowen M., McKinney N., Morrill W. E., Crabtree M. B., Kramer L. D., and Roehrig J. T. (2002) Complete Genome Sequences and Phylogenetic Analysis of West Nile Virus Strains Isolated from the United States, Europe, and the Middle East. Virology 298, 96–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Powell D. G. (2010) West Nile virus 2002. Equine Vet. Educ. 15, 66–66 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rossi S. L., Ross T. M., and Evans J. D. (2010) West Nile virus. Clin. Lab. Med. 30, 47–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Craven R. B., and Roehrig J. T. (2001) West Nile Virus. JAMA 286, 651–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dinman J. D. (2012) Mechanisms and implications of programmed translational frameshifting. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 3, 661–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harger J. W., Meskauskas A., and Dinman J. D. (2002) An “integrated model” of programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 448–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caliskan N., Katunin V. I., Belardinelli R., Peske F., and Rodnina M. V (2014) Programmed −1 frameshifting by kinetic partitioning during impeded translocation. Cell 157, 1619–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Melian E. B., Hinzman E., Nagasaki T., Firth A. E., Wills N. M., Nouwens A. S., Blitvich B. J., Leung J., Funk A., Atkins J. F., Hall R., and Khromykh A. A. (2010) NS1′ of flaviviruses in the Japanese encephalitis virus serogroup is a product of ribosomal frameshifting and plays a role in viral neuroinvasiveness. J. Virol. 84, 1641–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Melian E. B., Hall-Mendelin S., Du F., Owens N., Bosco-Lauth A. M., Nagasaki T., Rudd S., Brault A. C., Bowen R. A., Hall R. A., van den Hurk A. F., and Khromykh A. A. (2014) Programmed ribosomal frameshift alters expression of west nile virus genes and facilitates virus replication in birds and mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prow N. A., Hewlett E. K., Faddy H. M., Coiacetto F., Wang W., Cox T., Hall R. A., and Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. (2014) The Australian public is still vulnerable to emerging virulent strains of West Nile virus. Front. Public Health 2, 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keller B. C., Fredericksen B. L., Samuel M. A., Mock R. E., Mason P. W., Diamond M. S., and Gale M. (2006) Resistance to α/β interferon is a determinant of West Nile virus replication fitness and virulence. J. Virol. 80, 9424–9434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Botha E. M., Markotter W., Wolfaardt M., Paweska J. T., Swanepoel R., Palacios G., Nel L. H., and Venter M. (2008) Genetic determinants of virulence in pathogenic lineage 2 West Nile virus strains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 222–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Firth A. E., and Atkins J. F. (2009) A conserved predicted pseudoknot in the NS2A-encoding sequence of West Nile and Japanese encephalitis flaviviruses suggests NS1′ may derive from ribosomal frameshifting. Virol. J. 6, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bekaert M., Firth A. E., Zhang Y., Gladyshev V. N., Atkins J. F., and Baranov P. V (2010) Recode-2: new design, new search tools, and many more genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D69–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jacobson A. B., and Zuker M. (1993) Structural analysis by energy dot plot of a large mRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 233, 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rivas E., and Eddy S. R. (1999) A dynamic programming algorithm for RNA structure prediction including pseudoknots. J. Mol. Biol. 285, 2053–2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dirks R. M., and Pierce N. A. (2004) An algorithm for computing nucleic acid base-pairing probabilities including pseudoknots. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1295–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ren J., Rastegari B., Condon A., and Hoos H. H. (2005) HotKnots: heuristic prediction of RNA secondary structures including pseudoknots. RNA 11, 1494–1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grentzmann G., Ingram J. A., Kelly P. J., Gesteland R. F., and Atkins J. F. (1998) A dual-luciferase reporter system for studying recoding signals. RNA 4, 479–486 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacks T., Madhani H. D., Masiarz F. R., and Varmus H. E. (1988) Signals for ribosomal frameshifting in the Rous Sarcoma Virus gag-pol region. Cell 55, 447–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brierley I., Jenner A. J., and Inglis S. C. (1992) Mutational analysis of the “slippery-sequence” component of a coronavirus ribosomal frameshifting signal. J. Mol. Biol. 227, 463–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dinman J. D., Icho T., and Wickner R. B. (1991) A −1 ribosomal frameshift in a double-stranded RNA virus forms a Gag-pol fusion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 174–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Firth A. E., and Brierley I. (2012) Non-canonical translation in RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 93, 1385–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Belew A. T., Advani V. M., and Dinman J. D. (2011) Endogenous ribosomal frameshift signals operate as mRNA destabilizing elements through at least two molecular pathways in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2799–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Prud'homme B., Gompel N., Rokas A., Kassner V. A., Williams T. M., Yeh S. D., True J. R., and Carroll S. B. (2006) Repeated morphological evolution through cis-regulatory changes in a pleiotropic gene. Nature 440, 1050–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prud'homme B., Gompel N., and Carroll S. B. (2007) Emerging principles of regulatory evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8605–8612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ludwig M. Z., Patel N. H., and Kreitman M. (1998) Functional analysis of eve stripe 2 enhancer evolution in Drosophila: rules governing conservation and change. Development 125, 949–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baer A., Lundberg L., Swales D., Waybright N., Pinkham C., Dinman J. D., Jacobs J. L., and Kehn-Hall K. (2016) Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus induces apoptosis through the unfolded protein response activation of EGR1. J. Virol. 90, 3558–3572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hollidge B. S., Weiss S. R., and Soldan S. S. (2011) The role of interferon antagonist, non-structural proteins in the pathogenesis and emergence of arboviruses. Viruses 3, 629–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Green A. M., Beatty P. R., Hadjilaou A., and Harris E. (2014) Innate immunity to dengue virus infection and subversion of antiviral responses. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 1148–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baranov P. V., Gurvich O. L., Hammer A. W., Gesteland R. F., and Atkins J. F. (2003) Recode 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 87–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gibson D. G., Benders G. A., Axelrod K. C., Zaveri J., Algire M. A., Moodie M., Montague M. G., Venter J. C., Smith H. O., and Hutchison C. A. 3rd (2008) One-step assembly in yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 20404–20409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harger J. W., and Dinman J. D. (2003) An in vivo dual-luciferase assay system for studying translational recoding in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 9, 1019–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jacobs J. L., and Dinman J. D. (2004) Systematic analysis of bicistronic reporter assay data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, e160–e170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]