Abstract

Purpose:

Less than 10% of patients enrolled in clinical trials are minorities. The patient navigation model has been used to improve access to medical care but has not been evaluated as a tool to increase the participation of minorities in clinical trials. The Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials project used patient navigators (PNs) to enhance the recruitment of African Americans for and their retention in therapeutic cancer clinical trials in a National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center.

Methods:

Lay individuals were hired and trained to serve as PNs for clinical trials. African American patients potentially eligible for clinical trials were identified through chart review or referrals by clinic nurses, physicians, and social workers. PNs provided two levels of services: education about clinical trials and tailored support for patients who enrolled in clinical trials.

Results:

Between 2007 and 2014, 424 African American patients with cancer were referred to the Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials project. Of those eligible for a clinical trial (N = 378), 304 (80.4%) enrolled in a trial and 272 (72%) consented to receive patient navigation support. Of those receiving patient navigation support, 74.5% completed the trial, compared with 37.5% of those not receiving patient navigation support. The difference in retention rates between the two groups was statistically significant (P < .001). Participation of African Americans in therapeutic cancer clinical trials increased from 9% to 16%.

Conclusion:

Patient navigation for clinical trials successfully retained African Americans in therapeutic trials compared with non–patient navigation trial participation. The model holds promise as a strategy to reduce disparities in cancer clinical trial participation. Future studies should evaluate it with racial/ethnic minorities across cancer centers.

INTRODUCTION

The scientific value of cancer clinical trials has been established. Over the past several decades, remarkable progress in the treatment of cancer has been achieved through federally and industry-sponsored clinical trials. It also has been established that, for a number of scientific, methodologic, ethical, and social reasons, participation from all population groups is required for the success of clinical trials.1-3 Although the enrollment and retention of patients in cancer clinical trials is difficult among all population groups,4-7 it is especially challenging among racial/ethnic minorities.8 As a result, less than 10% of all patients with cancer enrolled in clinical trials are minorities.4

A number of barriers to the recruitment of minorities for, and their retention in, clinical trials have been described in the literature.9-12 Although minorities are just as willing to be involved in research studies as the general population,13,14 efforts to recruit and retain them in cancer clinical trials necessitate more labor-intensive approaches15-19 and more personal contacts.12,20,21 These findings speak to the importance of culturally appropriate strategies for recruitment of underrepresented minorities for, and their retention in, cancer clinical trials.

Patient navigation, or the use of lay community health workers to help patients overcome barriers in their communities and in the health care system, has been used to assist racial/ethnic minorities to obtain medical care.22-33 The model has also been used to recruit rural and low-income, mostly African American, patients into research studies, and projects report overall positive results.34-36 Despite the success of the patient navigation model in facilitating access to care, and evidence suggesting that patient navigators (PNs) can address barriers to clinical trial participation for ethnic/racial minorities,37-39 the patient navigation model has not been evaluated systematically as a tool for increasing the participation of minorities in clinical trials, and outcome measures to assess its effectiveness are scarce.40 The Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials (IMPaCT) project used patient navigation to enhance the recruitment of African Americans for, and their retention in, therapeutic cancer clinical trials in one racially and socioeconomically diverse National Cancer Institute (NCI) –designated comprehensive cancer center. This article reports on the project’s impact over a period of 8 years, between 2007 and 2014.

METHODS

IMPaCT was implemented at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Comprehensive Cancer Center beginning in 2007. The program’s goal was to educate African American patients with cancer about clinical trial participation and to assist with the recruitment of African American patients with cancer for, and their retention in, therapeutic cancer clinical trials. We hypothesized that recruitment for and retention in therapeutic cancer clinical trials would be higher among African American clinical trial participants who received patient navigation services compared with those who did not. The study was approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board for Human Use (Protocol X060406009).

Theoretical Model

The IMPaCT project was based on the Community Health Advisors Network (CHAN) model,35,41,42 which enables community members to serve as educators, navigators, and agents of change. The CHAN model is based on a social network theory about the health-enhancing effects of social support and community organization.43 The model reflects the fact that natural helpers or informal leaders in the community are recognized by their network (friends, families, and neighbors) as reliable sources of advice, help, and support.44 Community health advisors (CHAs) have often been used to provide a linkage between community members and the health care system.45 IMPaCT used the CHAN model to train community members as PNs who educate African American patients with cancer about clinical trials and help them overcome barriers to clinical trial participation.

Recruitment of PNs

Individuals who were already serving as CHAs for cancer prevention and control or embodied the qualities of CHAs were considered for these positions. The project team advertised the positions in the community, reviewed applications, and conducted a series of interviews. Two lay individuals matching the demographic characteristics of the patients (African American women from the Greater Birmingham area) were hired and trained to serve as full-time PNs.

Training of PNs

A training curriculum and training manual were developed. The training consisted of a background section and three modules. The background section educated PNs about the research team and the specific roles of team members and presented an overview of the research process. Module I offered an overview of the patient navigation as a concept, and training about cancer clinical trials using NCI Cancer Clinical Trials publications. Module II provided information about the navigation process, interacting with patients, patient interventions, and the clinic environment. In Module III, the PNs received case-management and data-management training, as well as training on how to explain the clinical trials consent process to potential participants. The training sessions were co-led by a diverse team of clinical trial research nurses, physicians, behavioral scientists, and health educators.

Program Implementation

Before the implementation of the program, a series of in-service presentations were conducted for clinical research nurses and clinical trial principal investigators to introduce them to the patient navigation initiative and to garner their support. A program implementation protocol, which included a PN work plan and a flowchart for PNs’ interaction with patients, was developed. Potential participants were identified in one of two ways: through reviews of electronic clinic schedules and patient charts by the IMPaCT nurse, or through referrals from nurses, physicians, and social workers.

Each day, the IMPaCT program manager received a list of patients scheduled to see a physician in oncology outpatient clinics within the next 3 days. The IMPaCT program manager identified the African American patients with cancer, reviewed the reasons for their clinic visit, and developed a list of patients likely to be offered participation in a clinical trial. This list of potential African American clinical trial participants was provided to each PN.

Before the scheduled clinic appointment, a PN contacted the patient by phone and asked if he or she would like to receive patient navigation support if offered to participate in clinical trial. If the patient agreed to patient navigation support, the PN met the patient in the waiting room before the scheduled clinic appointment to talk about clinical trials, obtain informed consent for participation in IMPaCT, and administer a needs assessment to determine what barriers the patient may have. If the time was not appropriate for needs assessment, the PN made arrangements with the patient to conduct the needs assessment at a different time.

Services Offered by PNs

Clinic-based education about clinical trials

PNs educated African American patients with cancer about clinical trials when they first contacted them by phone, when they met in the waiting room before the patient’s clinic appointment, or when the research nurse invited the PN to join her as she discussed with the patient the clinical trial and the consent form. When explaining clinical trials to potential participants, PNs used NCI Publication No. 97-2706: What Are Clinical Trials All About?46

Support for patients who enroll in clinical trials

Potential clinical trial participants who opted to receive patient navigation support completed a needs assessment. On the basis of the needs assessment, the PN determined if there were barriers to the patient’s participation in a clinical trial. Together with the patient, the PN developed a plan to address these barriers. The IMPaCT program manager helped PNs identify community resources that can be used for support of clinical trial participants. Services provided by PNs included assistance with transportation and lodging, reminder calls for appointments, referrals to social workers when appropriate, and linking the patient with social and community services and resources. In addition, PNs provided culturally appropriate peer support: they accompanied patients to clinic visits, especially when clinical trials were discussed, called patients to offer social and emotional support, encouraged patients to report symptoms/concerns to their physicians, and so forth.

PNs communicated regularly with clinic nurses and social workers to receive status updates and to monitor the trial participants’ attendance of clinic visits. PNs supplemented the institutional services provided to clinical trial participants without interfering with the clinical trial protocol. For example, they contacted participants before clinic visits to remind them of their appointments and after the visits to obtain feedback and ensure satisfaction with the visit. The preappointment contact allowed the PNs to assist with barriers that may have prevented the patient from making the visit, and the postvisit contact allowed the PNs to resolve issues that may have influenced the patient’s return visit or compliance with treatment protocols. Ultimately, the goal of the PNs was to help patients navigate the health care system, take advantage of available resources, and follow the clinical trial protocol.

Data Management and Analysis

Participant data were entered by PNs into a database designed to help manage their patient caseload and document their activities. The database was compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines and Institutional Review Board guidelines. To monitor progress, monthly summary reports of deidentified aggregate data were shared with members of the investigative team. As the IMPaCT project expanded and gained acceptability among clinicians, PNs were invited to attend the weekly meetings of the Comprehensive Cancer Center Clinical Trials Monitoring Committee and report on the patients they served.

Demographic information and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive summary statistics by IMPaCT participation status. Characteristics were compared using a χ2 test. For the trial completion rate, percentages with corresponding 95% CIs were calculated. The likelihood of trial completion was described using odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs.

RESULTS

Between 2007 and 2014, a total of 454 interventional cancer trials were available in the study institution. Of them, 72 were phase I, 39 were phase I/II, 167 were phase II, eight were phase II/III, 149 were phase III, and 16 were pilot trials. The majority of available trial protocols were in cancers of the brain and nervous system (n = 70), female breast (n = 61), lung (n = 34), lymphoid leukemia (n = 31), myeloid and monocytic leukemia (n = 30), ovary (n = 21), skin melanoma (n = 21), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 18), prostate (n = 16), kidney (n = 13), and lip, oral cavity, and pharynx (n = 13).

During the study period (2007 to 2014), a total of 432 African American patients with cancer were referred to IMPaCT. Of them, 272 (63%) participated in the program. Patients who did not participate in IMPaCT (n = 160, 37%) were not enrolled for the following reasons: 42% were ineligible for a clinical trial, 22% declined to participate in a clinical trial, 22% did not need assistance, 6% could not participate for other reasons (clinical trial was full, insurance did not cover trial, moved out of state, and so on), 5% were lost to contact, and 3% declined to participate in IMPaCT.

The majority of patients in both groups were 40 to 64 years old (67% IMPaCT, 71% non-IMPaCT), female (71% IMPaCT, 64% non-IMPaCT), and lived with someone (42% IMPaCT, 40% non-IMPACT). In terms of cancer type, they had breast cancer (31% IMPaCT, 25% non-IMPACT), lung cancer (13% IMPaCT, 10% non-IMPaCT), cervical cancer (9% IMPaCT, 14% non-IMPaCT), lymphoma (9% IMPaCT, 5% non-IMPaCT), head and neck cancer (7% IMPaCT, 8% non-IMPaCT), leukemia (5% IMPaCT, 4% non-IMPACT), and other cancers (26% IMPaCT, 34% non-IMPaCT). None of the differences between the two groups, however, were statistically significant (P > .05; Appendix Table A1, online only).

Among patients enrolled in a clinical trial, available socioeconomic information (educational attainment, income, health insurance status, and employment status) between patients who accepted patient navigation and those who did not was compared. Conclusions may be limited because of the proportion of missing information (ranging from 32% for health insurance status to 57% for income). However, the available data showed no difference between the two groups in terms of these socioeconomic variables.

During the course of the project, PNs provided a range of services in response to identified barriers (Table 1). Social and emotional support services included appointment reminders and confirmation of plans, escort and provision of Guest Services, assistance with paperwork, calls to identify community resources, linking of patients with programs such as the American Cancer Society’s Look Good Feel Better and Reach to Recovery, calls after a clinic visit to inquire about outcome, provision of emotional support, and counseling. Transportation services included making arrangements for or providing assistance with purchase of bus ticket, cab fare, airfare, parking, gas voucher, private transportation, Medicaid NET, Special Needs/Disability, and meal vouchers. Lodging services included making arrangements for, or providing assistance with stays at UAB Townhouse, American Cancer Society Hope Lodge, and area hotels. Insurance services included provision of Charity Care.

Table 1.

No. of IMPaCT Services Provided by Clinic or Disease Site

| Clinic or Disease Site | Transportation | Lodging | Insurance | Social and Emotional Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow transplantation | 4 | 1 | 0 | 43 |

| GI/genitourinary | 62 | 3 | 0 | 348 |

| Gynecologic oncology | 137 | 15 | 4 | 913 |

| Head and neck | 27 | 7 | 0 | 223 |

| Hematology-oncology | 168 | 13 | 2 | 958 |

| Invasive ductal breast carcinoma | 394 | 10 | 1 | 1,463 |

| Cooper Green Mercy Hospital | 28 | 0 | 0 | 86 |

| Lung | 25 | 12 | 0 | 415 |

| Neuro-oncology | 25 | 5 | 1 | 191 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| Radiation oncology | 45 | 2 | 0 | 344 |

| Solid tumors | 12 | 3 | 0 | 147 |

| Total | 927 | 71 | 8 | 5,152 |

Abbreviation: IMPaCT, Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials

As listed in Table 1, a total of 5,152 social support services, 927 transportation services, 71 lodging services, and eight insurance services were provided by PNs to program participants. On average, each PN had an active case load of 33 patients at any given time.

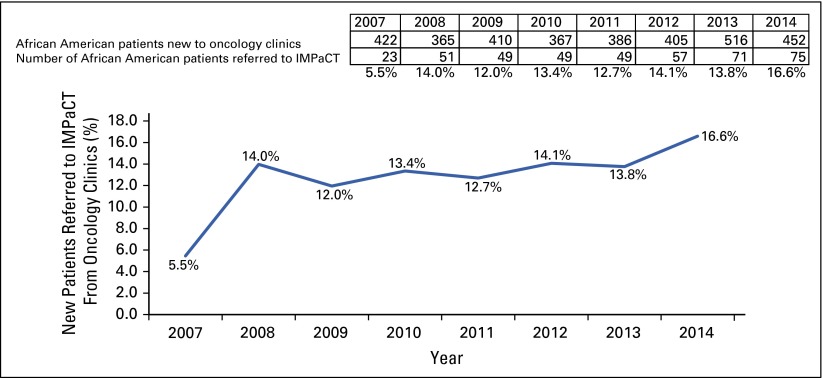

Over the duration of IMPaCT, referrals of African American patients from oncology clinics to cancer clinical trials increased more than three-fold, from 5.5% of all patients with cancer in 2007 to 16.6% of all patients with cancer in 2014 (Fig 1). Participation of African American patients in therapeutic clinical trials at the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center increased from 9% to 16% between 2007 and 2014.

FIG 1.

Referral rate to IMPaCT (Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials) of African American patients with cancer.

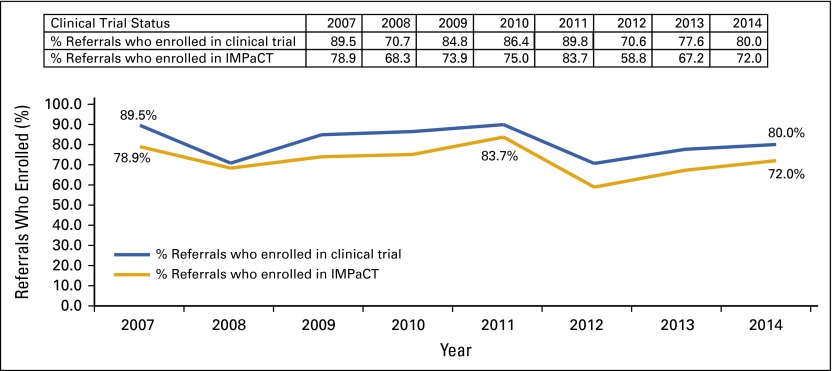

Of the African American patients referred to IMPaCT who were eligible for a clinical trial (n = 378), 304 (80.4%) enrolled in a trial and 272 (72%) enrolled in IMPaCT (ie, consented to receive patient navigation support); clinical trial enrollment and IMPaCT enrollment rates by year are presented in Figure 2.

FIG 2.

Clinical trial and IMPaCT (Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials) enrollment rates by year.

Of patients receiving patient navigation support, 74.5% completed the trial, compared with 37.5% of those who chose not to receive patient navigation support. The corresponding 95% CIs for the trial completion rates were 69.2% to 79.8% and 23.8% to 51.2%, respectively. IMPaCT-enrolled participants were 4.88 times (95% CI, 2.56 to 9.31) more likely to complete the clinical trial (P < .001; χ2 test). In both groups, patients withdrawn by physician because of toxicity, disease progression, or death were considered to have completed the trial. The reasons for not completing a clinical trial were not available for either group.

DISCUSSION

Patient navigation, which has been used extensively to increase access to medical care, has not been evaluated systematically as a strategy for increasing the participation of minorities in clinical trials,40 although interest in this field has been increasing and initial successes have been reported.47-52 IMPaCT used patient navigation to enhance the recruitment of African Americans for, and their retention in, therapeutic cancer clinical trials in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Between 2007 and 2014, the study reported a 72% average enrollment in therapeutic clinical trials of referred African American patients with cancer. These enrollment rates are consistent with the ones reported by other patient navigation studies.52-54 To our knowledge, however, this is the first lay patient navigation study to report increased minority participation in clinical trials (from 9% to 16%), as well as the first study in which the primary outcome measure is clinical trial completion rate.40 Importantly, the IMPaCT study doubled the clinical trial completion rate of African American trial participants (74.5% v 37.5%) by identifying and addressing potential barriers to compliance with treatment protocols and clinical trial completion.

The project was successful because it addressed both system- and patient-level barriers to participation of African Americans in cancer clinical trials. On the system level, the patient navigation model was integrated successfully into the clinical trial setting, and the PNs became part of the Comprehensive Cancer Center clinical trials team. As barriers to enrollment and retention were addressed appropriately by the trained PNs, the acceptability and the credibility of the program with clinicians and staff increased, resulting in improved referral rates by investigators and research nurses (from 5.5% to 16.6% between 2007 and 2014). This is one of the major reasons for the success of the program. As documented in the literature, patient enrollment in a clinical trial requires a gateway offer to participate, most frequently coming from a physician.55-57 Only 20% of those eligible for a clinical trial are explicitly offered the opportunity to enroll,58 and physicians tend to be selective about offering participation on the basis their perception of a patient’s likelihood of adhering to the protocol.59 Addressing these systemic barriers to the participation of minorities in clinical trials is critical and can be accomplished by integration of trained lay PNs into the clinical trial teams.

On the patient level, the project addressed individual barriers to clinical trial participation. This resulted in a clinical trial completion rate among African American patients that was comparable to the completion rate of white clinical trial participants.

Minority ethnicity and low socioeconomic status have been reported previously to be factors associated with clinical trial enrollment.4,5,8,60-62 The IMPaCT project demonstrated that patient navigation can address barriers to clinical trial participation among African American patients with cancer and significantly improve their retention in clinical trials. As the project made an impact on a systems level, PNs became legitimate members of the clinical and research teams. Over the project’s duration, both referral and enrollment rates in cancer clinical trials increased. Because of the study limitations of IMPaCT (nonrandomized design and lack of control group), it is not possible to estimate precisely what proportion of this increase is directly attributable to the patient navigation model. Further studies may consider pre/post or interrupted time series comparison of patient cohorts to determine if implementation of a patient navigation protocol results in higher rates of clinical trial enrollment and completion.

In addition, future research should address the cost-effectiveness of the patient navigation model for recruitment of racial/ethnic minorities for, and their retention in, clinical trials.40,63 Although the economic impact of patient navigation for diagnostic resolution has been discussed,64 such analyses should be performed in the context of clinical trial participation.65 The NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 mandated the inclusion of women and minorities in clinical trials. Recruitment of minority participants involves additional costs for implementation of recruitment strategies, methods, and tools that have been proven effective.66 If cancer clinical trials must include underrepresented minority populations, recruitment plans need to include adequate resources for their enrollment and retention.

Acknowledgment

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grant No. U54CA118948 and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Grant No. U24MD006970.

Appendix

Table A1.

Characteristics of Patients Referred to IMPACT (N = 432)

| Characteristic | Enrolled in IMPaCT | Did Not Enroll in IMPaCT |

|---|---|---|

| Total, No. (%) | 272 (63) | 160 (37) |

| Age group, years | ||

| < 40 | 12.13 | 7.50 |

| 40-64 | 66.91 | 71.25 |

| ≥ 65 | 20.96 | 21.25 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 70.96 | 63.75 |

| Male | 29.04 | 36.25 |

| Marital status | ||

| Lives with someone | 42.23 | 40.31 |

| Single | 31.92 | 40.31 |

| Separated or divorced | 15.00 | 13.18 |

| Widowed | 8.85 | 6.20 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Breast | 31.25 | 25.00 |

| Lung | 12.87 | 10.00 |

| Cervical | 8.82 | 14.38 |

| Lymphoma | 8.82 | 5.00 |

| Head and neck | 6.62 | 7.50 |

| Leukemia | 5.15 | 3.75 |

| Other | 26.47 | 34.38 |

NOTE. Data are presented as % unless indicated otherwise.

Abbreviation: IMPaCT, Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mona N. Fouad, Andres Forero, Michelle Y. Martin, Edward E. Partridge, Selwyn M. Vickers

Provision of study materials or patients: Andres Forero

Collection and assembly of data: Aras Acemgil, Andres Forero, Nedra Lisovicz

Data analysis and interpretation: Mona N. Fouad, Aras Acemgil, Sejong Bae, Andres Forero, Michelle Y. Martin, Gabriela R. Oates, Edward E. Partridge

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Patient Navigation As a Model to Increase Participation of African Americans in Cancer Clinical Trials

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jop.ascopubs.org/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Mona Fouad

No relationship to disclose

Aras Acemgil

No relationship to disclose

Sejong Bae

No relationship to disclose

Andres Forero

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Seattle Genetics (Inst), MedImmune (Inst), TRACON Pharma (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Abbvie (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Juno Therapeutics (Inst)

Nedra Lisovicz

No relationship to disclose

Michelle Y. Martin

No relationship to disclose

Gabriela R. Oates

No relationship to disclose

Edward E. Partridge

No relationship to disclose

Selwyn M. Vickers

No relationship to disclose

References

- 1.Corbie-Smith G, Miller WC, Ransohoff DF. Interpretations of ‘appropriate’ minority inclusion in clinical research. Am J Med. 2004;116:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander-Bridges M, Doan LL. Commentary on “increasing minority participation in clinical research”: a white paper from the endocrine society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4557–4559. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Institute of Medicine Committee on Cancer Clinical Trials NCGP: A national cancer clinical trials system for the 21st century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart JH, Bertoni AG, Staten JL, et al. Participation in surgical oncology clinical trials: Gender-, race/ethnicity-, and age-based disparities. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3328–3334. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9500-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du W, Gadgeel SM, Simon MS. Predictors of enrollment in lung cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;106:420–425. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young RC. Cancer clinical trials--a chronic but curable crisis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:306–309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1005843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colon-Otero G, Smallridge RC, Solberg LA, Jr, et al. Disparities in participation in cancer clinical trials in the United States : A symptom of a healthcare system in crisis. Cancer. 2008;112:447–454. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112:228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Killien M, Bigby JA, Champion V, et al. Involving minority and underrepresented women in clinical trials: The National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:1061–1070. doi: 10.1089/152460900445974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paskett ED, Reeves KW, McLaughlin JM, et al. Recruitment of minority and underserved populations in the United States: The Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities experience. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:847–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson JM, Trochim WM. An examination of community members’, researchers’ and health professionals’ perceptions of barriers to minority participation in medical research: An application of concept mapping. Ethn Health. 2007;12:521–539. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne MM, Tannenbaum SL, Glück S, et al. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Why are patients not participating? Med Decis Making. 2014;34:116–126. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13497264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baquet CR, Henderson K, Commiskey P, et al. Clinical trials: The art of enrollment. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. Brown DR, Fouad MN, Basen-Engquist K, et al: Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Ann Epidemiol 10:S13-S21, 2000 (suppl 8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00199-x. Fouad MN, Partridge E, Green BL, et al: Minority recruitment in clinical trials: A conference at Tuskegee, researchers and the community. Ann Epidemiol 10:S35-S40, 2000 (suppl 8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paskett ED, Katz ML, DeGraffinreid CR, et al. Participation in cancer trials: Recruitment of underserved populations. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2003;1:607–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28574. Durant RW, Wenzel JA, Scarinci IC, et al: Perspectives on barriers and facilitators to minority recruitment for clinical trials among cancer center leaders, investigators, research staff, and referring clinicians: Enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT). Cancer 120:1097-1105, 2014 (suppl 7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28572. Fouad MN, Johnson RE, Nagy MC, et al: Adherence and retention in clinical trials: A community-based approach. Cancer 120:1106-1112, 2014 (suppl 7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: Toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: The Patient Navigation Research Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju115. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2946-8. Wells KJ, Winters PC, Jean-Pierre P, et al: Effect of patient navigation on satisfaction with cancer-related care. Support Care Cancer 24:1729-1753, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5094. Paskett ED, Dudley D, Young GS, et al: Impact of patient navigation interventions on timely diagnostic follow up for abnormal cervical screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 25:15-21, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0772-1. Post DM, McAlearney AS, Young GS, et al: Effects of patient navigation on patient satisfaction outcomes. J Cancer Educ 30:728-735, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113:3391–3399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: An update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:237–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264. Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, et al: The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 117:3543-3552, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fouad M, Wynn T, Martin M, et al. Patient navigation pilot project: Results from the Community Health Advisors in Action Program (CHAAP) Ethn Dis. 2010;20:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: A randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health. 2008;85:114–124. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ko NY, Darnell JS, Calhoun E, et al. Can patient navigation improve receipt of recommended breast cancer care? Evidence from the National Patient Navigation Research Program. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2758–2764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: Current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104:848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews JO, Felton G, Wewers ME, et al. Use of community health workers in research with ethnic minority women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36:358–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_16. Fouad MN, Partridge E, Dignan M, et al: A community-driven action plan to eliminate breast and cervical cancer disparity: successes and limitations. J Cancer Educ 21:S91-S100, 2006 (suppl 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson RE, Green BL, Anderson-Lewis C, et al. Community health advisors as research partners: An evaluation of the training and activities. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:41–50. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petereit DG, Guadagnolo BA, Wong R, et al. Addressing cancer disparities among American Indians through innovative technologies and patient navigation: The Walking Forward Experience. Front Oncol. 2011;1:11. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2011.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krok-Schoen JL, Brewer BM, Young GS, et al. Participants’ barriers to diagnostic resolution and factors associated with needing patient navigation. Cancer. 2015;121:2757–2764. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz ML, Young GS, Reiter PL, et al. Barriers reported among patients with breast and cervical abnormalities in the patient navigation research program: Impact on timely care. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:e155–e162. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28570. Ghebre RG, Jones LA, Wenzel JA, et al: State-of-the-science of patient navigation as a strategy for enhancing minority clinical trial accrual. Cancer 120:1122-1130, 2014 (suppl 7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fouad MN, Nagy MC, Johnson RE, et al: The development of a community action plan to reduce breast and cervical cancer disparities between African-American and White women. Ethn Dis 14:S53-S60, 2004 (3 suppl 1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardy CM, Wynn TA, Huckaby F, et al. African American community health advisors trained as research partners: Recruitment and training. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:28–40. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, et al. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Israel BA. Social networks and social support: Implications for natural helper and community level interventions. Health Educ Q. 1985;12:65–80. doi: 10.1177/109019818501200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Office of Cancer Communications. National Cancer Institute: What are clinical trials all about? A booklet for patients with cancer. 97–2706. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1997.

- 46.Love MB, Gardner K, Legion V. Community health workers: Who they are and what they do. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:510–522. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Battaglia TA, Bak SM, Heeren T, et al. Boston Patient Navigation Research Program: The impact of navigation on time to diagnostic resolution after abnormal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1645–1654. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paskett ED, Katz ML, Post DM, et al. The Ohio Patient Navigation Research Program: Does the American Cancer Society patient navigation model improve time to resolution in patients with abnormal screening tests? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1620–1628. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bryant DC, Williamson D, Cartmell K, et al. A lay patient navigation training curriculum targeting disparities in cancer clinical trials. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2011;22:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moffitt K, Brogan F, Brown C, et al. Statewide cancer clinical trial navigation service. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:127–132. doi: 10.1200/JOP.200006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schapira L, Schutt R. Training community health workers about cancer clinical trials. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:891–898. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holmes DR, Major J, Lyonga DE, et al. Increasing minority patient participation in cancer clinical trials using oncology nurse navigation. Am J Surg. 2012;203:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Proctor JW, Martz E, Schenken LL, et al. A screening tool to enhance clinical trial participation at a community center involved in a radiation oncology disparities program. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:161–164. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0251. Wujcik D, Wolff SN: Recruitment of African Americans to National Oncology Clinical Trials through a clinical trial shared resource. J Health Care Poor Underserved 21:38-50, 2010 (suppl 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klabunde CN, Keating NL, Potosky AL, et al. A population-based assessment of specialty physician involvement in cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:384–397. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanai C, Nakajima TE, Nagashima K, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with advanced gastric cancer who declined to participate in a randomized clinical chemotherapy trial. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:148–153. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanai C, Nokihara H, Yamamoto S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer who declined to participate in randomised clinical chemotherapy trials. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1037–1042. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albrecht TL, Eggly SS, Gleason ME, et al. Influence of clinical communication on patients’ decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2666–2673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Joseph G, Dohan D. Diversity of participants in clinical trials in an academic medical center: The role of the ‘Good Study Patient?’. Cancer. 2009;115:608–615. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2109–2117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0162. Baquet CR, Ellison GL, Mishra SI: Analysis of Maryland cancer patient participation in National Cancer Institute-supported cancer treatment clinical trials. J Health Care Poor Underserved 20:120-134, 2009 (suppl 2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Go RS, Frisby KA, Lee JA, et al. Clinical trial accrual among new cancer patients at a community-based cancer center. Cancer. 2006;106:426–433. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26268. Whitley E, Valverde P, Wells K, et al: Establishing common cost measures to evaluate the economic value of patient navigation programs. Cancer 117:3618-3625, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bensink ME, Ramsey SD, Battaglia T, et al. Costs and outcomes evaluation of patient navigation after abnormal cancer screening: Evidence from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer. 2014;120:570–578. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Emanuel EJ, Schnipper LE, Kamin DY, et al. The costs of conducting clinical research. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4145–4150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fouad MN, Corbie-Smith G, Curb D, et al. Special populations recruitment for the Women’s Health Initiative: Successes and limitations. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:335–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]