Abstract

Background. This randomized, open trial compared regimens including 2 doses (2D) of human papillomavirus (HPV) 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in girls aged 9–14 years with one including 3 doses (3D) in women aged 15–25 years.

Methods. Girls aged 9–14 years were randomized to receive 2D at months 0 and 6 (M0,6; (n = 550) or months 0 and 12 (M0,12; n = 415), and women aged 15–25 years received 3D at months 0, 1, and 6 (n = 482). End points included noninferiority of HPV-16/18 antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for 2D (M0,6) versus 3D (primary), 2D (M0,12) versus 3D, and 2D (M0,6) versus 2D (M0,12); neutralizing antibodies; cell-mediated immunity; reactogenicity; and safety. Limits of noninferiority were predefined as <5% difference in seroconversion rate and <2-fold difference in geometric mean antibody titer ratio.

Results. One month after the last dose, both 2D regimens in girls aged 9–14 years were noninferior to 3D in women aged 15–25 years and 2D (M0,12) was noninferior to 2D (M0,6). Geometric mean antibody titer ratios (3D/2D) for HPV-16 and HPV-18 were 1.09 (95% confidence interval, .97–1.22) and 0.85 (.76–.95) for 2D (M0,6) versus 3D and 0.89 (.79–1.01) and 0.75 (.67–.85) for 2D (M0,12) versus 3D. The safety profile was clinically acceptable in all groups.

Conclusions. The 2D regimens for the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in girls aged 9–14 years (M0,6 or M0,12) elicited HPV-16/18 immune responses that were noninferior to 3D in women aged 15–25 years.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT01381575.

Keywords: 2-dose schedule, HPV, human papillomavirus, immunogenicity, cervical cancer, AS04, Adjuvant System containing 50 µg 3-O-desacyl-4′-monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) adsorbed on aluminum salt (500 µg Al3+), IgG, CMI, cell-mediated immunity, GMT, geometric mean antibody titer

Persistent infection with a high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) type is a prerequisite for cervical cancer [1–3]; therefore, prophylactic HPV vaccination is expected to substantially reduce the burden of this disease, particularly in countries without effective cervical screening programs. The licensed vaccines HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted (Cervarix; GSK Vaccines) and HPV-6/11/16/18 (Gardasil; Merck & Co) were first approved as regimen including 3 doses (3D) with administration over a 6-month period. Reduced dose schedules could make vaccination easier to implement and more affordable, creating the potential for higher vaccination coverage and improved cervical cancer protection [4].

Evaluation of schedules including 2 doses (2D) of the HPV vaccine for girls was first prompted by the observation that 3D schedules elicited HPV-16/18 antibody titers approximately 2-fold higher in girls than in young women [5, 6], the age group in which efficacy was demonstrated in clinical studies [7–13]. A preliminary immunogenicity study evaluating the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine showed that 2D given at months 0 and 6 to girls aged 9–14 years was immunologically noninferior 1 month after the last dose to 3D given at months 0, 1, and 6 (M0,1,6) to women aged 15–25 years, and that antibody titers were sustained at high levels for up to 5 years [14–16]. However, the preliminary study was not powered to formally compare immunogenicity between groups beyond 1 month after the last dose. Therefore, the current large phase III study was designed to formally evaluate noninferiority and safety of 2 alternative 2D schedules (months 0 and 6 [M0,6] and months 0 and 12 [M0,12]) in girls aged 9–14 years compared with 3D in women aged 15–25 years over a 3-year period. The study is ongoing, and here we report data up to month 12 or month 13 (depending on the group).

METHODS

The study is an open trial of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine with 3 parallel groups (Supplementary Figure 1). Girls aged 9–14 years were randomized (1:1) to receive 2D (M0,6 or M0,12) and women aged 15–25 years were allocated to receive 3D (M0,1,6). Each 0.5-mL vaccine dose contained HPV-16 and HPV-18 L1 viruslike particles (20 µg each) adjuvanted with the adjuvant system AS04, containing 50 µg 3-O-desacyl-4′-monophosphoryl lipid A adsorbed on aluminum salt (500 µg Al3+). Doses were administered by intramuscular injection in the deltoid region of the nondominant arm.

The primary objective was to evaluate noninferiority of HPV-16/18 antibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of 2D (M0,6) in girls aged 9–14 years versus 3D in women aged 15–25 years 1 month after the last dose. Secondary comparisons were to evaluate noninferiority of HPV-16/18 antibodies (ELISA) for 2D (M0,6) versus 3D at 6, 12, 18, and 30 months after the last dose, for 2D (M0,12) versus 3D, and for 2D (M0,12) versus 2D (M0,6) at 1, 6, and 12 months after the last dose. Other secondary objectives included HPV-16/18 neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) by pseudovirion-based neutralization assay (PBNA), cell-mediated immunity (CMI) in terms of frequencies of HPV-16/18-specific T-cells and memory B-cells, reactogenicity, and safety. Prespecified exploratory objectives were HPV-31/45 antibodies (ELISA) and CMI. and post-hoc exploratory objectives were avidity of HPV-16/18 antibodies.

For the current analysis, HPV-16/18 ELISA, PBNA, CMI, and safety data are available up to 6 months after the last dose (month 12) for the 3D (M0,1,6) and 2D (M0,6) groups and 1 month after the last dose (month 13) for the 2D (M0,12) group. HPV-16/18 antibody avidity and HPV-31/45 ELISA and CMI data are available up to 1 month after the last dose (month 7) for the 3D (M0,1,6) and 2D (M0,6) groups (Supplementary Figure 1). The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01381575) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol and other materials were reviewed and approved by independent ethics committees or institutional review boards.

Participants

Healthy girls and women aged 9–25 years at the time of first vaccination were enrolled at 33 sites in Canada, Germany, Italy, Taiwan, and Thailand. Enrollment started in June 2011. The last visit of the vaccination phase was in January 2013. Women of childbearing potential were to be abstinent or to have used adequate contraceptive precautions for 30 days before first vaccination and agreed to continue such precautions for 2 months after the last vaccine dose. Women were excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding, had a confirmed or suspected immunosuppressive or immunodeficient condition or an allergic disease likely to be exacerbated by any component of the vaccine, or had previously received HPV vaccination, 3-O-desacyl-4′-monophosphoryl lipid A, or AS04 adjuvant. Written informed consent was obtained from the subject or subject's parent/legally acceptable representative. Informed assent was obtained from subjects below the legal age of consent.

Randomization and Masking

The randomization list was generated by GSK Vaccines using a standard SAS program. A randomization blocking scheme (1:1 ratio) ensured that balance between the two 2D schedules was maintained. Treatment allocation at each site used a central randomization system on the Internet. Within each age stratum, the randomization algorithm used a minimization procedure accounting for center. Investigators and participants were not blinded to group assignment. Enrollment in each group was stratified by age to give an approximately equal distribution of girls aged 9–11 years and 12–14 years in 2D groups and women aged 15–19 years and 20–25 years in the 3D group.

Immunogenicity

Time points for blood sample collection are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. HPV-16/18 antibodies were measured by ELISA for all subjects. HPV-16/18 nAbs and CMI and HPV-31/45 antibodies (ELISA) and CMI were measured in a subset of subjects (the first 50 in each age stratum in each group at preselected sites). HPV-16/18 antibody avidities at month 7 were measured in a subset of randomly selected subjects from the 2D (M0,6) and 3D (M0,1,6) groups in the according-to-protocol immunogenicity cohort (ATP-I, evaluable subjects meeting all eligibility criteria, complying with the procedures and intervals defined in the protocol with no elimination criteria, for whom data were available).

HPV-16/18/31/45 antibodies were determined with viruslike particle–specific ELISA [17, 18]. Seronegativity was defined as a titer lower than the assay cutoff (8 ELISA units [EU]/mL for HPV-16, 7 EU/mL for HPV-18, and 59 EU/mL for HPV-31/45). HPV-16/18 antibody avidities were measured with modified ELISA in which chaotropic agent (1 mol/L sodium thiocyanate) was added to disrupt the interaction between antibody and antigen [19]. The avidity index was expressed as the ratio (percentage) of antigen-specific antibody titers with to those without the chaotropic agent. HPV-16/18 nAbs were determined using PBNA [17]. Seronegativity was defined as a titer lower than the assay cutoff (40 ED50 [effective dose producing 50% response] for each antigen). Antigen-specific memory B-cells were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay [18, 20]. CD4+ T-cells producing immune markers (CD40L, interferon γ, interleukin 2, or tumor necrosis factor α) in response to in vitro stimulation using a pool of HPV peptides were quantified with intracellular cytokine staining, followed by flow cytometry [18, 21].

Safety

Solicited local and general symptoms were recorded on diary cards for 7 days after each vaccination. Unsolicited symptoms were recorded for 30 days after each vaccination. Grade 3 symptoms were defined as redness or swelling >50 mm in diameter, fever >39°C, urticaria distributed on ≥4 body areas, and, for other symptoms, as preventing normal activity. Pregnancies and outcomes, serious adverse events, medically significant adverse events, and potential immune-mediated diseases were reported throughout the study.

Statistical Methods

The target enrollment of 1428 subjects (476 per group) was estimated to give approximately 1140 evaluable subjects (380 per group) for evaluation of the primary objective 1 month after the last dose, assuming that 20% of subjects would be nonevaluable. This sample size allowed detection of a 5% difference between the 2D (M0,6) and 3D groups for seroconversion rates and a 2-fold difference for geometric mean antibody titers (GMTs) with 98% power.

For the primary objective, noninferiority was demonstrated if the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the seroconversion difference (3D-2D) was <5% and the upper limit of the 95% CI for the GMT ratio (3D/2D) was <2. The criteria were assessed sequentially with GMT ratios assessed only if noninferiority was demonstrated for seroconversion. If the primary objective was reached, noninferiority of HPV-16/18 immune responses (ELISA) was to be sequentially assessed using the criteria defined above for other comparisons. The noninferiority limits were based on margins set for previous studies [5, 22–24]. Confirmatory testing was not performed for other secondary or exploratory objectives.

Seroconversion and seropositivity rates (with exact 95% CI) and GMTs (with 95% CI) were calculated by prevaccination status. GMTs were computed by taking the anti-log of the mean of the log titer transformations. Antibody titers below the assay cutoff were given an arbitrary value of half the cutoff in this calculation. Two-sided standardized asymptotic 95% CIs for differences between groups in the percentage of seroconverted subjects were computed. Two-sided 95% CIs of GMT ratios between groups were computed using an analysis of variance on log10-transformed titers, including vaccine group as a fixed effect.

Noninferiority analyses were based on initially seronegative subjects in the ATP-I. Supplementary analyses were done for initially seronegative subjects in the total vaccinated cohort (TVC) (subjects who received ≥1 vaccine dose for whom data were available). Descriptive summaries of immunogenicity data were done by prevaccination serostatus for the ATP-I and TVC, with the primary focus being those subjects who were seronegative before vaccination.

Descriptive comparisons were made between HPV-16/18 GMTs measured by ELISA in our study, GMTs in women aged 15–25 years who cleared a natural infection and mounted an immune response in a previous efficacy trial (NCT00122681) [25], and GMTs from the plateau phase (month 45–50) of a long-term efficacy study in women aged 15–25 years (NCT00120848) [8]. Descriptive comparisons were also made between HPV-16/18 GMTs measured with PBNA in our study and GMTs in women aged 18–45 years who had cleared a natural infection and mounted an immune response in a previous immunogenicity trial (NCT00423046) [20]. Safety data are summarized descriptively for the TVC. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 and PROC StatXact 8.1 software.

RESULTS

Study Population

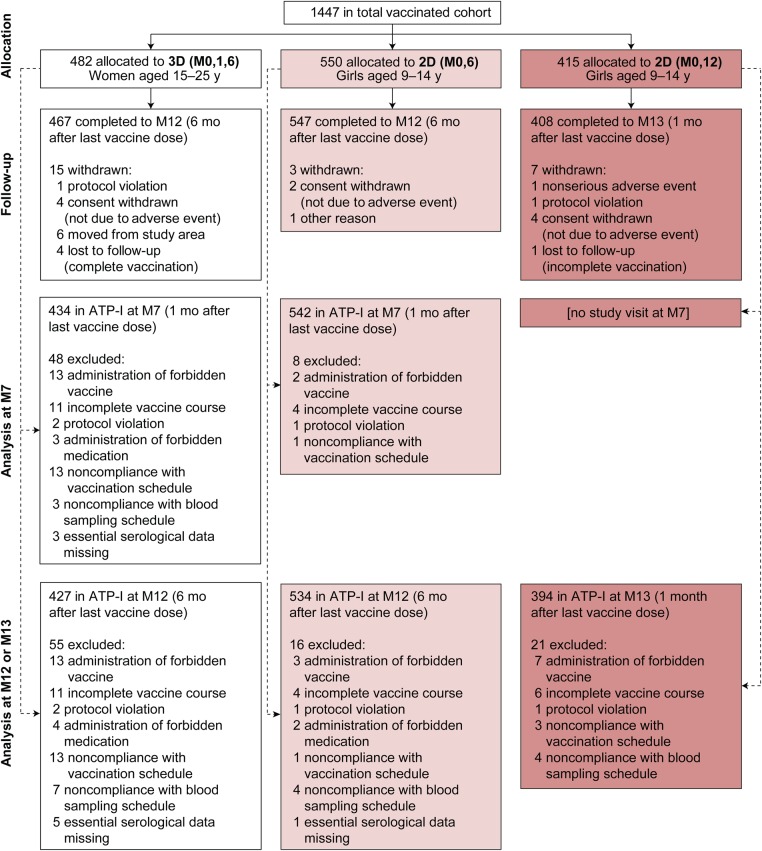

A total of 1447 subjects were enrolled, and all subjects received ≥1 vaccine dose (Figure 1). The month 7 ATP-I for the primary noninferiority analysis included 434 of 482 participants (90.0%) in the 3D group and 542 of 550 (98.5%) in the 2D (M0,6) group. The month 12/13 ATP-I for secondary and exploratory immunogenicity analyses included 427 of 482 (88.6%) in the 3D group, 534 of 550 (97.1%) in the 2D (M0,6) group, and 394 of 415 (94.9%) in the 2D (M0,12) group. A larger proportion of subjects in the 3D group than in 2D groups were excluded from the ATP-I owing to an incomplete vaccination course or noncompliance with the vaccination schedule (Figure 1). The treatment groups were well balanced with regard to demographic characteristics and baseline HPV-16/18 serostatus, except that, by design, older subjects were enrolled in the 3D group (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study. The imbalance between the numbers of subjects randomized to the 2D (M0,6) and 2D (M0,12) groups was due to the unavailability of the vaccine allocated to the latter group at some study sites, forcing the randomization system to automatically allocate subjects from that group to the M0,6 group. This technical issue did not affect the validity of the study, because sufficient subjects were still randomized to the M0,12 group to allow evaluation of study objectives. Abbreviations: 2D (M0,6), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 6; 2D (M0,12), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 12; 3D (M0,1,6), 3-dose schedule administered at months 0, 1, and 6; ATP-I, according-to-protocol immunogenicity cohort; M7, month 7; M12, month 12; M13, month 13.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Serostatus in the TVC and ATP-I Populationsa

| Population | Women Aged 15–25 y |

Girls Aged 9–14 y |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D (M0,1,6) | 2D (M0,6) | 2D (M0,12) | |

| TVC | |||

| Subjects, No. | 482 | 550 | 415 |

| Age at 1st vaccine dose, mean (SD), y | 19.6 (3.05) | 11.6 (1.59) | 11.4 (1.55) |

| Age stratum, No. (%) | |||

| 9–11 y | … | 264 (48.0) | 212 (51.1) |

| 12–14 y | … | 286 (52.0) | 203 (48.9) |

| 15–19 y | 238 (49.4) | … | … |

| 20–25 y | 244 (50.6) | … | … |

| Geographic ancestry, No. (%) | |||

| Caucasian heritage | 263 (54.6) | 289 (52.5) | 224 (54.0) |

| Asian heritage | 212 (44.0) | 250 (45.5) | 182 (43.9) |

| African heritage/African American | 3 (0.6) | 6 (1.1) | 6 (1.4) |

| Other | 4 (0.8) | 5 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) |

| HPV-16 baseline serostatus by ELISA, No. (%) | |||

| Seronegative | 388 (80.8) | 493 (90.0) | 373 (89.9) |

| Seropositive | 92 (19.2) | 55 (10.0) | 42 (10.1) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| HPV-18 baseline serostatus by ELISA, No. (%) | |||

| Seronegative | 422 (87.9) | 499 (91.7) | 388 (94.4) |

| Seropositive | 58 (12.1) | 45 (8.3) | 23 (5.6) |

| Missing | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| ATP-I at 7 mo | |||

| Subjects, No. | 434 | 542 | …b |

| Age at 1st vaccine dose, mean (SD), y | 19.6 (3.05) | 11.6 (1.60) | … |

| Geographic ancestry, No. (%) | |||

| White heritage | 227 (52.3) | 282 (52.0) | … |

| Asian heritage | 201 (46.3) | 249 (45.9) | … |

| African heritage/African American | 3 (0.7) | 6 (1.1) | … |

| Other | 3 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | … |

| HPV-16 baseline serostatus by ELISA, No. (%) | |||

| Seronegative | 352 (81.5) | 488 (90.4) | … |

| Seropositive | 80 (18.5) | 52 (9.6) | … |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | … |

| HPV-18 baseline serostatus by ELISA, No. (%) | |||

| Seronegative | 382 (88.4) | 493 (92.0) | … |

| Seropositive | 50 (11.6) | 43 (8.0) | … |

| Missing | 2 | 6 | … |

| ATP-I at 12 or 13 mo | |||

| Subjects, No. | 427 | 534 | 394 |

| Age at 1st vaccine dose, mean (SD), y | 19.5 (3.04) | 11.5 (1.60) | 11.4 (1.55) |

| Geographic ancestry, No. (%) | |||

| White heritage | 222 (52.0) | 275 (51.5) | 210 (53.3) |

| Asian heritage | 199 (46.6) | 248 (46.4) | 175 (44.4) |

| African heritage/African American | 3 (0.7) | 6 (1.1) | 6 (1.5) |

| Other | 3 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | 3 (0.8) |

| HPV-16 baseline serostatus by ELISA, No. (%) | |||

| Seronegative | 347 (81.6) | 480 (90.2) | 355 (90.1) |

| Seropositive | 78 (18.4) | 52 (9.8) | 39 (9.9) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| HPV-18 baseline serostatus by ELISA, No. (%) | |||

| Seronegative | 376 (88.5) | 485 (91.9) | 369 (94.6) |

| Seropositive | 49 (11.5) | 43 (8.1) | 21 (5.4) |

| Missing | 2 | 6 | 4 |

Abbreviations: 2D (M0,6), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 6; 2D (M0,12), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 12; 3D (M0,1,6), 3-dose schedule administered at months 0, 1, and 6; ATP-I, according-to-protocol immunogenicity cohort; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HPV, human papillomavirus; SD, standard deviation; TVC, total vaccinated cohort.

a Seronegative status was defined as an antibody titer lower than the assay cutoff before vaccination (8 ELISA units [EU]/mL for HPV-16 and 7 EU/mL for HPV-18).

b There was no month 7 visit for the 2D (M0,12) group, so the ATP-I is not defined for this group at this time point.

Noninferiority Evaluation

The primary noninferiority objective was met. In the ATP-I, HPV-16/18 immune responses (ELISA) for the 2D (M0,6) schedule in girls aged 9–14 years were noninferior to 3D in women aged 15–25 years 1 month after the last dose in terms of seroconversion and GMTs (Table 2). Noninferiority criteria were met for all secondary comparisons assessed (Table 2). Results were consistent between the ATP-I and TVC. Noninferiority was demonstrated for all comparisons in the TVC (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Noninferiority Assessment of HPV-16 and HPV-18 Antibody Responses (ELISA) for Initially Seronegative Subjects in the ATP-Ia

| Antibody and Group | Age, y | No. | Seroconversion (95% CI), % | GMT (95% CI), EU/mL | Seroconversion Difference (95% CI), %b | GMT Ratio (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D (M0,6) vs 3D (M0,1,6) 1 mo after the last dose (primary noninferiority objective)d | ||||||

| HPV-16 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,6) | 9–14 | 488 | 100 (99.2–100) | 9400.1 (8818.3–10020.4) | 0.00 (−1.08 to .78) | 1.09 (.97–1.22) |

| 3D (M0,1,6) | 15–25 | 352 | 100 (99.0–100) | 10234.5 (9258.3–11313.6) | ||

| HPV-18 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,6) | 9–14 | 493 | 100 (99.3–100) | 5909.1 (5508.9–6338.4) | 0.00 (−1.00 to .77) | 0.85 (.76–.95) |

| 3D (M0,1,6) | 15–25 | 382 | 100 (99.0–100) | 5002.6 (4572.6–5473.1) | ||

| 2D (M0,12) vs 3D (M0,1,6) 1 mo after the last dose (secondary noninferiority objective)e,f | ||||||

| HPV-16 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,12) | 9–14 | 355 | 100 (99.0–100) | 11449.7 (10635.3–12326.5) | 0.00 (−1.10 to 1.07) | 0.89 (.79–1.01) |

| 3D (M0,1,6) | 15–25 | 347 | 100 (98.9–100) | 10175.6 (9202.4–11251.8) | ||

| HPV-18 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,12) | 9–14 | 369 | 100 (99.0–100) | 6656.3 (6153.6–7200.2) | 0.00 (−1.01 to 1.03) | 0.75 (.67–.85) |

| 3D (M0,1,6) | 15–25 | 376 | 100 (99.0–100) | 5018.7 (4583.4–5495.3) | ||

| 2D (M0,12) vs 2D (M0,6) 1 mo after the last dose (secondary noninferiority objective)e,g | ||||||

| HPV-16 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,12) | 9–14 | 355 | 100 (99.0–100) | 11449.7 (10635.3–12326.5) | 0.00 (−.79 to 1.07) | 0.82 (.74–.91) |

| 2D (M0,6) | 9–14 | 480 | 100 (99.2–100) | 9396.0 (8808.3–10022.9) | ||

| HPV-18 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,12) | 9–14 | 369 | 100 (99.0–100) | 6656.3 (6153.6–7200.2) | 0.00 (−.79 to 1.03) | 0.89 (.80–.99) |

| 2D (M0,6) | 9–14 | 485 | 100 (99.2–100) | 5920.8 (5515.9–6355.4) | ||

| 2D (M0,6) vs 3D (M0,1,6) 6 mo after the last dose (secondary noninferiority objective)e,h | ||||||

| HPV-16 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,6) | 9–14 | 480 | 100 (99.2–100) | 2663.2 (2489.4–2849.2) | 0.00 (−1.10 to .79) | 1.25 (1.10–1.40) |

| 3D (M0,1,6) | 15–25 | 347 | 100 (98.9–100) | 3317.2 (2983.7–3688.0) | ||

| HPV-18 | ||||||

| 2D (M0,6) | 9–14 | 485 | 100 (99.2–100) | 1526.3 (1409.8–1652.4) | 0.00 (−1.01 to .79) | 0.99 (.87–1.12) |

| 3D (M0,1,6) | 15–25 | 376 | 100 (99.0–100) | 1505.4 (1355.4–1672.0) | ||

Abbreviations: 2D (M0,6), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 6; 2D (M0,12), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 12; 3D (M0,1,6), 3-dose schedule administered at months 0, 1, and 6; ATP-I, according-to-protocol immunogenicity cohort; CI, confidence interval; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EU, ELISA units; GMT, geometric mean antibody titer; HPV, human papillomavirus.

a Two-sided 95% CIs of GMT ratios between groups were computed using an analysis of variance on log10 transformed titers, including vaccine group as a fixed effect. Seronegative status was defined as an antibody titer lower than the assay cutoff before vaccination (8 EU/mL for HPV-16 and 7 EU/mL for HPV-18).

b Noninferiority was confirmed if the upper limit of the 95% CI for difference in seroconversion rates was below the predefined limit of 5%.

c Noninferiority was confirmed if the upper limit of the 95% CI for the GMT ratio was below the predefined limit of 2.

d The month 7 ATP-I was used for assessment of the primary immunogenicity objective. The seroconversion difference in this grouping represents 3D − 2D (M0,6), and the GMC ratio, 3D/2D (M0,6).

e The month 12/13 ATP-I was used for assessment of secondary immunogenicity objectives. Note that the number of subjects included in the month 12/13 ATP-I was slightly smaller than for the month 7 ATP-I, leading to small differences in calculated GMT values 1 month after the last vaccine dose, depending on whether the noninferiority comparison was a primary or secondary objective.

f The seroconversion difference in this grouping represents 3D − 2D (M0,12), and the GMC ratio, 3D/2D (M0,12).

g The seroconversion difference in this grouping represents 2D (M0,6) − 2D (M0,12), and the GMC ratio, 2D (M0,6)/2D (M0,12).

h The seroconversion difference in this grouping represents 3D − 2D (M0,6), and the GMC ratio, 3D/2D (M0,6).

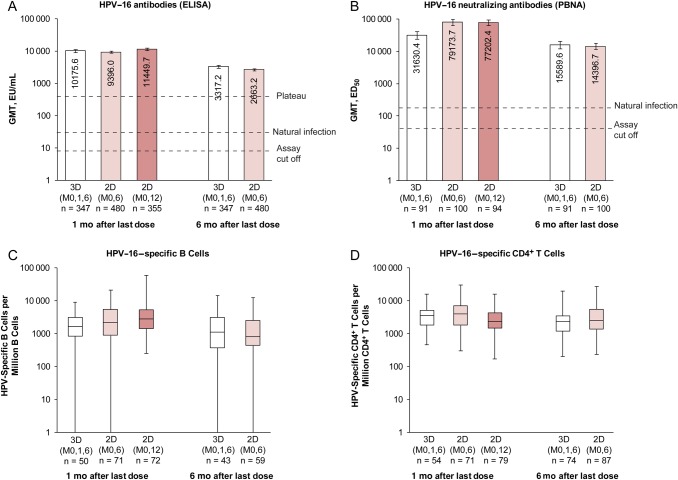

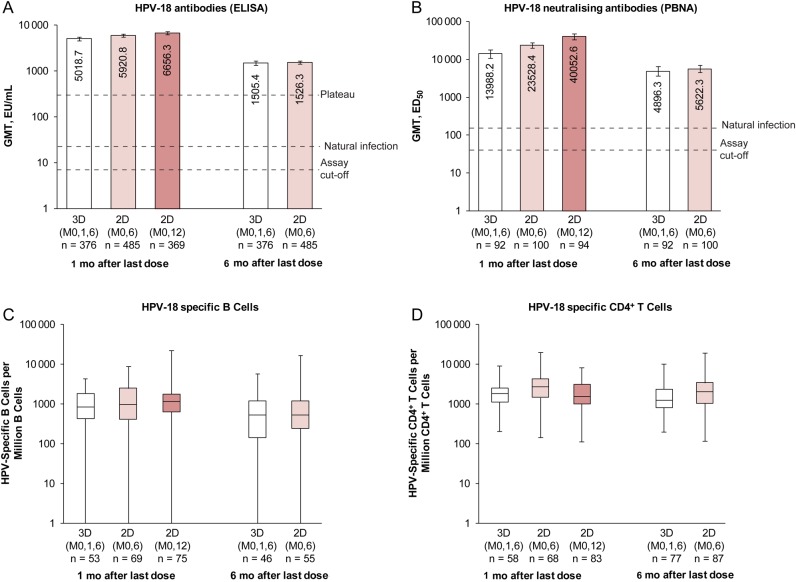

Immune Responses to Vaccine HPV-16 and HPV-18

In the ATP-I, all initially seronegative subjects in each group seroconverted for HPV-16/18 antibodies by ELISA, and nAbs by PBNA, 1 month after the last dose (Table 2). Subjects in the 2D (M0,6) and 3D groups remained seropositive 6 months after the last dose. For initially seronegative subjects in the ATP-I, HPV-16/18 GMTs (ELISA) and B-cell and CD4+ T-cell responses 1 month after the last dose were within the same range in girls aged 9–14 years who received 2D and women aged 15–25 years who received 3D (Figures 2 and 3). HPV-16/18 nAb titers 1 month after the last dose seemed higher, based on descriptive data, in girls aged 9–14 years who received 2D than in women aged 15–25 years who received 3D, and values were within the same range 6 months after the last dose (for 2D [M0,6] and 3D schedules) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 immune responses for initially seronegative subjects in the month 12/13 according-to-protocol immunogenicity cohort. A, B, Bars represent GMTs and associated 95% confidence intervals; numbers within each bar are the GMTs for each group, and initially seronegative subjects were those who had an antibody titer lower than the assay cutoff (8 EU/mL for ELISA; 40 ED50 for PBNA). C, D, Box plots show median, lower and upper quartiles, and minimum and maximum values; initially seronegative subjects were those who were seronegative at ELISA. Natural infection represents HPV-16 GMT measured with ELISA in women aged 15–25 years who had cleared a natural infection in Study HPV-008 (29.8 EU/mL) [25] or measured with PBNA in women aged 18–45 years who had cleared a natural infection in Study HPV-010 (180.1 ED50) [20]; plateau, HPV-16 GMT measured with ELISA at month 45–50, which was 397.8 (344.7–459.1) EU/mL for women aged 15–25 years in the total vaccinated cohort from Study HPV-007 [8]. Abbreviations: 2D (M0,6), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 6 to girls aged 9–14 years; 2D (M0,12), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 12 to girls aged 9–14 years; 3D (M0,1,6), 3-dose schedule administered at months 0, 1, and 6 to women aged 15–25 years; ED50, effective dose producing 50% response; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EU, ELISA units; GMT, geometric mean antibody titer; PBNA, pseudovirion-based neutralization assay.

Figure 3.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)18 immune responses for initially seronegative subjects in the month 12/13 according-to-protocol immunogenicity cohort. A, B, Bars represent GMTs and associated 95% confidence intervals; numbers within each bar are the GMTs for each group; initially seronegative subjects were those who had an antibody titer lower than the assay cutoff (7 EU/mL for ELISA; 40 ED50 for PBNA). C, D, Box plots show median, lower and upper quartiles, and minimum and maximum values; initially seronegative subjects were those who were seronegative at ELISA. Natural Infection represents HPV-18 GMT measured with ELISA for women aged 15–25 years who had cleared a natural infection in Study HPV-008 (22.6 EU/mL) [25] or with PBNA for women aged 18–45 years who had cleared a natural infection in Study HPV-010 (137.3 ED50) [20]; plateau, HPV-18 GMT measured with ELISA at month 45–50, which was 297.3 (258.2 to 342.2) EU/mL for women aged 15–25 years in the total vaccinated cohort from Study HPV-007 [8]. Abbreviations: 2D (M0,6), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 6 to girls aged 9–14 years; 2D (M0,12), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 12 to girls aged 9–14 years; 3D (M0,1,6), 3-dose schedule administered at months 0, 1, and 6 to women aged 15–25 years; ED50, effective dose producing 50% response; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EU, ELISA units; GMT, geometric mean antibody titer; PBNA, pseudovirion-based neutralization assay.

Similar results were observed in the ATP-I and TVC regardless of baseline serostatus (Supplementary Tables 2–9). In the ATP-I, geometric mean avidity indices (95% CI) 1 month after the last vaccine dose for HPV-16 and HPV-18, respectively, were 92.8% (89.8%–96.0%) and 84.8% (81.8%–88.0%) for the 3D group and 88.8% (86.9%–90.9%) and 89.6% (86.9%–92.3%) for the 2D (M0,6) group (Supplementary Figure 2). Among low antibody responders (in the lowest decile for GMTs 1 month after the last dose), HPV-16/18 GMTs seemed higher in 2D groups than in the 3D group (Supplementary Table 10).

Cross-reactive Immune Responses to Nonvaccine HPV-31 and HPV-45

At month 7, cross-reactive HPV-31/45 antibody and CMI responses were of similar magnitude in girls aged 9–14 years who received 2D (M0,6) and women aged 15–25 years who received 3D (Supplementary Figure 3). There was large variability in HPV-31– and HPV-45–specific memory B-cell responses, but median values were within a similar range in the 2D and 3D groups. Similar results were observed in the ATP-I and TVC regardless of baseline immune status (Supplementary Tables 2–9).

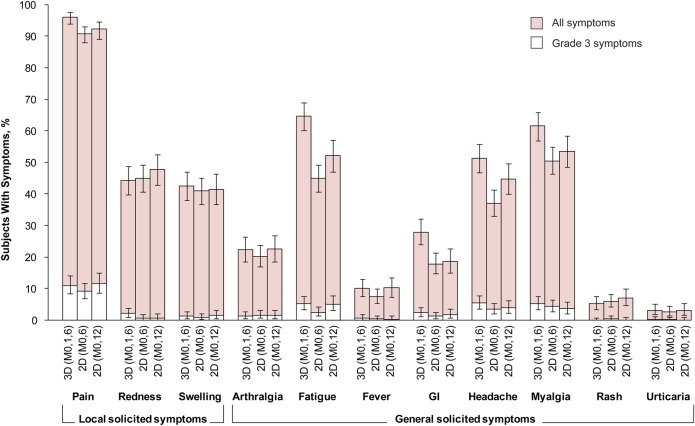

Reactogenicity and Safety

The incidence of local and general solicited symptoms overall per subject, during the 7-day period after each dose, is shown in Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 11. Incidence overall per dose is shown in Supplementary Table 12. Pain at the injection site was the most frequently solicited local symptom (reported by >90% of subjects in each group). The incidence of grade 3 pain ranged from 9%–12% across groups. Fatigue (45%–65% of subjects), myalgia (51%–62%), and headache (37%–51%) were the most frequently solicited general symptoms. Individual grade 3 solicited general symptoms were reported by <6% of subjects in each group.

Figure 4.

Incidence of local and general solicited symptoms during the 7-day postvaccination period overall per subject (total vaccinated cohort). Error bars represent exact 95% confidence intervals. There were 480 subjects with ≥1 documented dose and a returned symptom sheet for the 3D group, 550 for the 2D (M0,6) group, and 411 for the 2D (M0,12) group. Fever was defined as oral or axillary temperature ≥37.5°C; grade 3 fever, as oral or axillary temperature >39.0°C; grade 3 redness/swelling, an area at the local injection site >50 mm in diameter. For all other symptoms, a grade 3 event was defined as one that prevented normal everyday activities. Abbreviations: 2D (M0,6), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 6 to girls aged 9–14 years; 2D (M0,12), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 12 to girls aged 9–14 years; 3D (M0,1,6), 3-dose schedule administered at months 0, 1, and 6 to women aged 15–25 years; GI, gastrointestinal.

During the 30-day postvaccination period, ≥1 unsolicited symptom was reported for 34.6%, 17.6%, and 17.8% of subjects in 3D, 2D (M0,6), and 2D (M0,12) groups, respectively (Table 3). Nasopharyngitis was the most common unsolicited symptom (reported by approximately 6% of subjects in each group). The incidence of grade 3 unsolicited symptoms was low (3.5%, 0.4% and 1.4% in the 3D, 2D (M0,6), and 2D (M0,12) groups, respectively).

Table 3.

Safety Outcomes Until the End of the Secondary Vaccination Phase in the TVCa

| Outcome | Women Aged 15–25 y |

Girls Aged 9–14 y |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D (M0,1,6) (n = 482) | 2D (M0,6) (n = 550) | 2D (M0,12) (n = 415) | |

| Unsolicited symptoms during 30-d postvaccination period | |||

| Subjects with ≥1 event, No. (%) [95% CI] | 167 (34.6) [30.4–39.1] | 97 (17.6) [14.5–21.1] | 74 (17.8) [14.3–21.9] |

| Events reported, No | 273 | 131 | 101 |

| Deaths, No. (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serious adverse events | |||

| Subjects with ≥1 event, No. (%) [95% CI] | 15 (3.1) [1.8–5.1] | 12 (2.2) [1.1–3.8] | 11 (2.7) [1.3–4.7] |

| Events reported, No. | 18 | 18 | 11 |

| Medically significant adverse events | |||

| Subjects with ≥1 event, No. (%) [95% CI] | 124 (25.7) [21.9–29.9] | 99 (18.0) [14.9–21.5] | 61 (14.7) [11.4–18.5] |

| Events reported, No. | 212 | 167 | 110 |

| Potential immune-mediated diseases | |||

| Subjects with ≥1 event, No. (%) [95% CI] | 2 (0.4) [0.1–1.5] | 2 (0.4) [0.0–1.3] | 2 (0.5) [0.1–1.7] |

| Events reported, No. | 3 | 3 | 2 |

Abbreviations: 2D (M0,6), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 6; 2D (M0,12), 2-dose schedule administered at months 0 and 12; 3D (M0,1,6), 3-dose schedule administered at months 0, 1, and 6; CI, confidence interval; TVC, total vaccinated cohort.

a The secondary vaccination phase ended at month 12 for subjects in the 3D (M0,1,6) and 2D (M0,6) groups and at month 13 for subjects in the 2D (M0,12) group.

Serious adverse events and potential immune-mediated diseases were reported for a similar proportion of subjects in each group (Table 3). None of the serious adverse events was assessed by investigators as causally related to vaccination. One nonserious potential immune-mediated disease of seventh cranial nerve paralysis in the 3D group was considered to have a possible causal relationship to vaccination; the onset of this event was 18 days after the first vaccine dose, and the event resolved after 13 days without sequelae. Twenty-five pregnancies were reported (24 in the 3D group and 1 in the 2D [M0,12] group). Of these, 18 resulted in the delivery of a normal infant (including the pregnancy in the 2D [M0,12] group), 1 was an ectopic pregnancy, 1 was terminated by elective abortion, 1 was a stillbirth, and pregnancies 4 were ongoing at the time of reporting. No apparent congenital anomalies were reported.

DISCUSSION

HPV-16/18 antibody responses (ELISA) to the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a 2D (M0,6) schedule to girls aged 9–14 years were noninferior to those elicited by the standard 3D (M0,1,6) schedule in women aged 15–25 years, both 1 and 6 months after the last dose, confirming results from a preliminary immunogenicity study [14, 15]. The high and similar avidity of HPV-16/18 antibodies in 2D (M0,6) and 3D groups suggest that the quality of the immune response is also comparable for both schedules [19]. The immunological noninferiority of 2D (M0,12) compared with both 3D (M0,1,6) and 2D (M0,6) 1 month after the last dose, and the clinically acceptable safety profiles of the different schedules further support the use of 2D schedules of the HPV-16/18 vaccine in girls, with flexibility around the administration of the second dose.

Serum nAbs, thought to be the major basis of protection conferred by HPV vaccines [26, 27], were also in the same range or higher for the 2D schedules versus the 3D schedule. Similar responses were observed in 2D and 3D groups against nonvaccine HPV types 31 and 45 (to month 7 only), suggesting that a 2D schedule may give cross-protection similar to that observed previously [11]. B-cell and CD4+ T-cell responses, which may be important for long-term vaccine-induced protection [28–30], were also similar in all groups. Interim results from an ongoing study of an extended (months 0, 6, and 60) schedule of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in a real-world setting in Mexico also showed immunological noninferiority of the 2D schedule compared with the standard 3D schedule in girls aged 9–10 years [31].

Because efficacy studies in 9–14-year-old girls are not feasible for ethical and practical reasons, most regulatory authorities allow immunobridging data to infer efficacy in preteen/adolescents. Because immunogenicity profiles were similar for 2D schedules in girls and the 3D schedule in women, we infer that 2D of the HPV-16/18 vaccine administered to preteen/adolescent girls will give a similar level of protection compared with 3D in young women, in whom high vaccine efficacy has been demonstrated in clinical trials [8–11, 25]. Preliminary evidence that efficacy can be achieved with <3 doses was also observed in a post-hoc nonrandomized analysis of the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial (CVT) [32, 33] and a post-hoc analysis combining data from the CVT and the PATRICIA (Papilloma Trial against Cancer in Young Adults) trial [34]. Four years after vaccination of women aged 15–25 years, 1 and 2 doses of the HPV-16/18 vaccine seemed to protect against cervical HPV-16/18 infections, similar to the protection provided by the 3D schedule. Two doses separated by 6 months also provided some cross-protection. In the CVT, HPV-16/18 antibody responses in women who received 2D were durable over 4 years of follow-up, with GMTs being at least 24- and 14-fold higher, respectively, than those observed in natural infection [33].

On the basis of data from the present study, and the preliminary immunogenicity study [14], the HPV-16/18 vaccine has received marketing authorization in several countries for a 2D schedule in preteen/adolescent girls, with flexibility around the timing of the second dose, from 5 to 13 months after the first dose. Clinical trials have also been conducted to investigate reduced number of doses or extended schedules of the HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine [35–38], and this vaccine has also recently received marketing authorization for a 2D schedule in adolescents. An ongoing head-to-head trial (NCT01462357) showed that a 2D schedule of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine elicited superior HPV-16/18 antibody responses in adolescent girls compared with 2D and 3D of the HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine 1 and 6 months after the last vaccine dose [39].

Girls vaccinated at a young age will require many years of protection against HPV infection to prevent HPV-associated cancers; therefore, longevity of immune responses at a sufficiently high level are important for a 2D schedule. Follow-up in the current study is ongoing over a 3-year period and is required to determine longer-term noninferiority. In addition, follow-up of the 2D (M0,12) schedule is currently complete only to 1 month after the last dose, so evidence comparing the two 2D regimens is limited. Information from further follow-up time points is needed for a more complete picture of immunogenicity. However, data from the preliminary immunogenicity study in girls aged 9–14 years who received a 2D (M0,6) schedule of the HPV-16/18 vaccine showed that antibody titers remained high over a 5-year period, and modeling predicts that antibody titers could persist for ≥ 21 years [16].

The reactogenicity and safety profile of the HPV-16/18 vaccine in the current trial was clinically acceptable in both 2D and 3D groups and generally similar to that reported elsewhere [40]. The proportion of subjects reporting some types of solicited general symptoms, and unsolicited symptoms, was numerically lower for 2D groups than the 3D group. These apparent differences could be due to the different ages of subjects enrolled in the 2D and 3D groups, rather than the reduced number of doses, but a previous study showed no difference in reactogenicity on the basis of age for the standard 3D schedule [5], strengthening the implicit notion that 2D are less reactogenic than 3D.

A strength of our study is that it offers a comprehensive evaluation of the immunogenicity of 2D schedules, including ELISA, nAbs, CMI, and avidity assessments, with consistency of results across these end points. The evaluation of 2 alternative 2D schedules (M0,6 and M0,12) was a unique feature of this trial and supported registration of a flexible 2D schedule of the HPV-16/18 vaccine. The diversity of geographic and ethnic origins, and group sample sizes were also much larger in our study than in other trials comparing 2D versus 3D schedules [14, 35]. However, our study was not powered for secondary and exploratory immunogenicity end points (PBNA, CMI, avidity), which were measured in a smaller subset of subjects, and statistical comparisons were not made between groups for these immunogenicity end points or for reactogenicity.

In summary, we show that 2D schedules of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered over a 6- or 12-month interval to girls aged 9–14 years are immunologically noninferior to the standard 3D schedule in women aged 15–25 years, the age group in which high vaccine efficacy has previously been demonstrated in clinical trials. The flexibility around the timing of the second dose, giving the option of annual vaccination over 2 consecutive years, is an added benefit. Reduced dose schedules of HPV vaccines may facilitate vaccination implementation and reduce cost, allowing for higher vaccination coverage and potentially more girls being protected from cervical cancer.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the study participants and the staff members of the different study sites for their contribution to the study. We also thank the following contributors to the study and/or publication: Germany: Andreas Clad (deceased). Italy: Erika Albanese, Roberto Cacciani, and Rocco Iudici. Thailand: Chayapa Phasomsap, Passorn Punyahotra, Ekasit Kowitdamrong, Torsak Bunupuradah, and Chitsanu Pancharoen. Laboratory support: Bénédicte Brasseur, Muriel Carton, Francis Dessy, Dinis Fernandes Ferreira, Edwin Kolp, Laurence Luyten, Valérie Mohy, Philippe Moris, and Zineb Soussi Mouhssin (all from GSK Vaccines). Global study management: Geneviève Meiers and Mihaela Lascar (GSK Vaccines). Regulatory affairs support: Christine Van Hoof and Nicolas Folschweiller (GSK Vaccines). Study data management: Sheetal Verlekar (GSK Vaccines). Statistical support: Srikanth Emmadi, Amulya Jayadev, and Marie Lebacq (GSK Vaccines). Publication writing assistance: Julie Taylor (Peak Biomedical Ltd, on behalf of GSK Vaccines). Editorial assistance and publication coordination: Jean-Michel Heine and Jérôme Leemans (Keyrus Biopharma, on behalf of GSK Vaccines), Dirk Saerens (formerly Keyrus Biopharma, on behalf of GSK Vaccines), Stéphanie Delval (XPE Pharma & Science, on behalf of GSK Vaccines), and Bruno Baudoux (Business & Decision Life Sciences, on behalf of GSK Vaccines).

Author contributions. L.-M. H., C.-H. C., T. F. S., S. E., C. G., P. D., S. P., P. V. S., M. Hezareh, D. D., F. T., and F. S. participated in study design. T. P., L.-M. H., C.-H. C., R.-B. T., T. F. S., S. E., L. F., C. G., S. M., P. D., M. Horn, M. K., S. P., S. D. S., D. F., B. D. M., and P. V. S. acquired the data. L.-M. H., C.-H. C., R.-B. T., T. F. S., and S. E. extracted the data. S. E., P. V. S., and F. T. performed the analysis. T. P., L.-M. H., C.-H. C., T. F. S., S. E., C. G., S. M., P. D., M. K., S. D. S., D. F., B. D. M., P. V. S., D. D., F. T., and F. S. interpreted data. T. P., L.-M. H., C.-H. C., R.-B. T., T. F. S., S. E., L. F., C. G., S. M., P. R., P. D., M. Horn, and M. K. provided study material or subjects. P. V. S. and F. T. participated in statistical analysis. L. F., S. P., S. D. S., D. F., and B. D. M. did the laboratory testing. L.-M. H., C.-H. C., R.-B. T., T. F. S., S. E., L. F., C. G., S. M., P. D., D. D., F. T., and F. S. supervised the study group. All authors had full access to the complete final study reports, reviewed the manuscript draft(s), and gave final approval to submit for publication.

Disclaimer. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals designed the study in collaboration with investigators and coordinated gathering, analysis, and interpretation of data and writing of the report. Investigators from the study group gathered data for the trial and cared for the study subjects. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The manuscript was developed and coordinated by the authors in collaboration with an independent medical writer and publication managers, working on behalf of GSK Vaccines.

Financial support. This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA.

Potential conflicts of interest. T. P. and M. K. received a grant through their respective institutions from the GSK group of companies. L.-M. H. received grants through his institution from the GSK group of companies and also received consultancy fees for participation to HPV expert board, and payment for educational presentation from the GSK group of companies. R.-B. T. received funding from the GSK group of companies through his institution. T. F. S. received fees for board membership, consultancy, and payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus, from the GSK group of companies. S. E. received grants from the GSK group of companies, Crucell, Novartis, Pfizer and Roche through her institution; payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus from the GSK group of companies, Crucell, Novartis, and Astrazeneca and also received support for travel to meetings for the study from the GSK group of companies. L. F. received support for travel to meeting for the study from the GSK group of companies. C. G. received payments for board membership and lectures including service on speakers bureaus from Sanofi Pasteur MSD, Merck and GSK group of companies. S. M. received grants through her institution from the GSK group of companies, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur MSD; consultancy fees from Pfizer; and payment for lectures from Merck and Pfizer, including service on speakers bureaus. P. R. received funding through his institution for the conduct of the clinical trial and support for travel to meetings for the study from the GSK group of companies; he also holds stock option from the GSK group of companies. P. D. received a grant from the GSK group of companies through his institution for the conduct of this trial; received grants through his institution from Sanofi Pasteur MSD, Berna Crucell, Novartis, and Pfizer for the conduct of other clinical trials; and received support for travel to meetings from the GSK group of companies, consultancy fees for participation to advisory boards and payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD. M. Horn received consultancy fees from the GSK group of companies and Novartis; support for travel to meetings for the study from the GSK group of companies; payment for board membership from Novartis; payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, development of educational presentations, and travel, accommodation, and meeting expenses from the GSK group of companies, Sanofi Pasteur MSD, and Novartis. S. P., S. D. S., D. F., B. D. M., P. V. S., D. D., F. T., and F. S. are employees of the GSK group of companies. M. Hezareh is a Chiltern International consultant for the GSK group of companies. F. T. holds stock options from the GSK group of companies. D. D. and F. S. hold shares and stock options from the GSK group of companies. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003; 16:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN et al. Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85:958–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 1999; 189:12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jit M, Brisson M, Laprise JF, Choi YH. Comparison of two dose and three dose human papillomavirus vaccine schedules: cost effectiveness analysis based on transmission model. BMJ 2015; 350:g7584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen C, Petaja T, Strauss G et al. Immunization of early adolescent females with human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine containing AS04 adjuvant. J Adolesc Health 2007; 40:564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block SL, Nolan T, Sattler C et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in male and female adolescents and young adult women. Pediatrics 2006; 118:2135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364:1757–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM et al. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet 2006; 367:1247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet 2009; 374:301–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehtinen M, Paavonen J, Wheeler CM et al. Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler CM, Castellsague X, Garland SM et al. Cross-protective efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by non-vaccine oncogenic HPV types: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13:100–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FUTURE II Study Group. Prophylactic efficacy of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in women with virological evidence of HPV infection. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:1438–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ault KA, FUTURE II Study Group. Effect of prophylactic human papillomavirus L1 virus-like-particle vaccine on risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, grade 3, and adenocarcinoma in situ: a combined analysis of four randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2007; 369:1861–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson LM et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a 2-dose schedule compared to the licensed 3-dose schedule: results from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin 2011; 7:1374–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson LM et al. Immune response to the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a 2-dose or 3-dose schedule up to 4 years after vaccination: results from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:1155–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romanowski B, Schwarz TF, Ferguson L et al. Sustained immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine administered as a two-dose schedule in adolescent girls: five-year clinical data and modeling predictions from a randomized study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12:20–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dessy FJ, Giannini SL, Bougelet CA et al. Correlation between direct ELISA, single epitope-based inhibition ELISA and pseudovirion-based neutralization assay for measuring anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 antibody response after vaccination with the AS04-adjuvanted HPV-16/18 cervical cancer vaccine. Hum Vaccin 2008; 4:425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Einstein MH, Baron M, Levin MJ et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 vaccine and the HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine for oncogenic non-vaccine types HPV-31 and HPV-45 in healthy women aged 18–45 years. Hum Vaccin 2011; 7:1359–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boxus M, Lockman L, Fochesato M et al. Antibody avidity measurements in recipients of Cervarix® vaccine following a two-dose schedule or a three-dose schedule. Vaccine 2014; 32:3232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einstein MH, Baron M, Levin MJ et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity and safety of CervarixTM and Gardasil® human papillomavirus (HPV) cervical cancer vaccines in healthy women aged 18–45 years. Hum Vaccin 2009; 5:705–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Einstein MH, Baron M, Levin MJ et al. Comparative immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 vaccine and HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine: follow-up from months 12–24 in a phase III randomized study of healthy women aged 18–45 years. Hum Vaccin 2011; 7:1343–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Sicilia J, Schwarz TF, Carmona A et al. Immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine coadministered with combined diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-inactivated poliovirus vaccine to girls and young women. J Adolesc Health 2010; 46:142–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmeink CE. Co-administration of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine with hepatitis B vaccine: randomized study in healthy girls. Vaccine 2011; 29:9276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen C, Breindahl M, Aggarwal N et al. Randomized trial: immunogenicity and safety of coadministered human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine and combined hepatitis A and B vaccine in girls. J Adolesc Health 2012; 50:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369:2161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanley M. Immune responses to human papillomavirus. Vaccine 2006; 24:S16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longet S, Schiller JT, Bobst M, Jichlinski P, Nardelli-Haefliger D. A murine genital-challenge model is a sensitive measure of protective antibodies against human papillomavirus infection. J Virol 2011; 85:13253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science 2002; 298:2199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crotty S, Felgner P, Davies H et al. Cutting edge: long-term B cell memory in humans after smallpox vaccination. J Immunol 2003; 171:4969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traggiai E, Puzone R, Lanzavecchia A. Antigen dependent and independent mechanisms that sustain serum antibody levels. Vaccine 2003; 21(suppl 2):S35–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazcano-Ponce E, Stanley M, Munoz N et al. Overcoming barriers to HPV vaccination: non-inferiority of antibody response to human papillomavirus 16/18 vaccine in adolescents vaccinated with a two-dose vs. a three-dose schedule at 21 months. Vaccine 2014; 32:725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreimer AR, Rodriguez AC, Hildesheim A et al. Proof-of-principle evaluation of the efficacy of fewer than three doses of a bivalent HPV16/18 vaccine. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103:1444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safaeian M, Porras C, Pan Y et al. Durable antibody responses following one dose of the bivalent human papillomavirus L1 virus-like particle vaccine in the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013; 6:1242–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreimer AR, Struyf F, Del Rosario-Raymundo MR et al. Efficacy of fewer than three doses of an HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: combined analysis of data from the Costa Rica Vaccine and PATRICIA trials. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:775–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobson SR, McNeil S, Dionne M et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309:1793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolen KK, Gelinas L, Franzen L et al. Age of recipient and number of doses differentially impact human B and T cell immune memory responses to HPV vaccination. Vaccine 2012; 30:3572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuzil KM, Canh dG, Thiem VD et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of alternative schedules of HPV vaccine in Vietnam: a cluster randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA 2011; 305:1424–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaMontagne DS, Thiem VD, Huong VM, Tang Y, Neuzil KM. Immunogenicity of quadrivalent HPV vaccine among girls 11 to 13 years of age vaccinated using alternative dosing schedules: results 29 to 32 months after third dose. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:1325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leung TF, Liu AP, Lim FS et al. Comparative immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine and HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine administered according to 2- and 3-dose schedules in girls aged 9–14 years: results to month 12 from a randomized trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:1689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angelo MG, David MP, Zima J et al. Pooled analysis of large and long-term safety data from the human papillomavirus-16/18-AS04-adjuvanted vaccine clinical trial programme. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014; 23:466–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.