Abstract

Background and Aims:

Crohn’s disease [CD] and ulcerative colitis [UC] are chronic diseases associated with a substantial utilisation of healthcare resources. We aimed to estimate the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], CD, and UC and to describe and compare healthcare utilisation and drug treatment in CD and UC patients.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study of all patients with a recorded IBD diagnosis in Stockholm County, Sweden. Data on outpatient visits, hospitalisations, surgeries, and drug treatment during 2013 were analysed.

Results:

A total of 13 916 patients with IBD were identified, corresponding to an overall IBD prevalence of 0.65% [CD 0.27%, UC 0.35%, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified 0.04%]; 49% of all IBD patients were treated with IBD-related drugs. Only 3.6% of the patients received high-dose corticosteroids, whereas 32.4% were treated with aminosalicylates [CD 21.2%, UC 41.0%, p < 0.0001]. More CD patients were treated with biologicals compared with UC patients [CD 9.6%, UC 2.9%, p < 0.0001] and surgery was significantly more common among CD patients [CD 3.0%, UC 0.8%, p < 0.0001].

Conclusions:

This study indicates that patients with CD are the group with the highest medical needs. Patients with CD utilised significantly more healthcare resources [including outpatient visits, hospitalisations, and surgeries] than UC patients. Twice as many CD patients received immunomodulators compared with UC patients and CD patients were treated with biologicals three times more often. These results highlight that CD remains a challenge and further efforts are needed to improve care in these patients.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, healthcare utilisation, drug treatment

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] is a broad term including conditions with chronic or recurring immune response and inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. The two IBD entities are Crohn’s disease [CD] that affects predominantly the terminal ileum and/or the colorectum, and ulcerative proctocolitis [UC] that only involves the large bowel and/or the rectum. It is estimated that the worldwide prevalence of IBD is 0.40%.1 A recent population-based study found that the prevalence of IBD in Sweden is 0.65%.2

Clinical guidelines3,4 recommend individualised medical treatment depending on the type, distribution, and severity of the disease. Medicines available for IBD include aminosalicylates, antibiotics, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologicals (anti-tumour necrosis factor [TNF] and anti-integrin antibodies). However, treatment with aminosalicylates is more efficacious in UC compared with CD5,6 and it is not recommended as maintenance treatment for CD.4 Severe inflammation not responding to any pharmacotherapy may require major surgical intervention, such as colectomy or small bowel resection, with or without a temporary or permanent colostomy or ileostomy.

Since CD and UC are diseases with lifelong chronicity, the affected individuals consume substantial healthcare resources.7,8 Observational studies on healthcare utilisation in IBD populations are therefore needed to understand how these patients interact with the healthcare system. The relapsing-remitting nature of IBD with a range of drugs prescribed in ambulatory care and administered in the hospital setting makes it challenging to conduct comprehensive analyses of the total burden of IBD on healthcare systems.

Sweden has a universal publicly funded healthcare system with all residents having access to healthcare.9 Healthcare is decentralised and administered by county councils responsible for organising and paying for healthcare services. A number of registers have been established at the national level to collect data on outpatient visits and hospitalisations as well as drugs dispensed in the ambulatory setting.10 Furthermore, by 2009 the majority of healthcare providers in Sweden had adopted electronic health record [EHR] systems.11 The presence of the unique personal identity number [PIN] given to each Swedish resident12 enables researchers to link national registers and data from EHRs and other healthcare data sources at both regional and national levels. These unique record linkage opportunities combined with the complete population healthcare coverage help overcome some of limitations of data sources that exist in other countries.

In the current study we linked data from administrative health databases and EHRs to estimate the prevalences of IBD, UC, and CD in the region and to describe healthcare utilisation and drug treatment in these patients. Furthermore, we aimed to analyse differences between CD and UC with regard to healthcare utilisation and drug treatment.

2. Methods

This was a cross-sectional population-based study of all patients with a recorded diagnosis of IBD in Stockholm County that, with its 2.1 million inhabitants, accounts for 22% of the Swedish population.

2.1. Data sources

2.1.1. Regional data warehouse [VAL]

The main data source used in this study was the regional healthcare data warehouse of Stockholm County Council [called VAL].13 This data warehouse includes information on all contacts with healthcare financed by the County Council. Data for primary care are available from 2003 and for secondary care and hospitalisations from 1993. The International Classification of Diseases Version 10 [ICD-10]14 has been used since 1997. VAL also contains demographic information on patient age, sex, migration, and death. Since July 2010, information on prescription drugs dispensed in the ambulatory setting is also included. These data come from the same data source as the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register with the population coverage of over 99%.15 The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] classification system is used to code dispensed drugs.16 Drug utilisation can also be identified in VAL using procedure codes and ATC codes in outpatient specialist and hospitalisation data.

2.1.2. Electronic health records

Since VAL might have limited information on biologicals administered in the hospital setting [mainly infliximab], data extractions were also performed from three major hospitals in Stockholm County involved in the care of IBD patients. Within the study period, these hospitals accounted for 94% of all TNF-inhibitors used in Stockholm County. This was done to build a complete drug utilisation profile across the inpatient and outpatient setting. Data on biological therapy were extracted from the EHR prescribing module [EHR software: TakeCare, CompuGroup Medical, Sweden] using techniques described previously.17 Data from EHRs were linked to VAL data using the PIN.

For one large private gastroenterology specialist clinic [Stock holm Gastro Centre], VAL had incomplete information on diagnoses. Therefore, to address this limitation, information on all patients with IBD was extracted directly from the clinic’s EHR system [MediDoc, CompuGroup Medical, Sweden] and linked to VAL data using the PIN.

2.2. Selection of study population

The study population comprised all individuals with a diagnosis of IBD recorded either in primary or in secondary care from January 1, 1997 until December 31, 2012. The following ICD-10 codes were used to select IBD patients: K50, Crohn’s disease; K51, Ulcerative colitis; and K52.3, Indeterminate colitis. We restricted our study population to only those patients who have had at least two diagnoses recorded by a physician on two separate occasions.2 Patients who moved out of the region or died before or during 2013 were excluded from analyses.

As different IBD diagnoses might be documented during a patient’s medical history due to either a shift of diagnosis or incorrect registration in the records, we used the two most recent diagnoses preceding the index date [January 1, 2013] to classify patients as either CD [two ICD-10 codes K50, either as primary or as secondary diagnosis] or UC [two ICD-10 codes K51]. If the two most recent diagnoses were not the same, then patient was classified as inflammatory bowel disease unclassified [IBDU] which also included ICD-10 code K52.3, Indeterminate colitis.

2.3. Healthcare utilisation

Healthcare utilisation was described over a 1-year period from January 1, 2013 until December 31, 2013. Hospitalisations and outpatient physician visits were included.

Healthcare utilisation was described at three levels.

All healthcare utilisation—comprised healthcare utilisation regardless of cause/diagnoses.

Healthcare utilisation related to IBD—comprised healthcare utilisation related to IBD defined either as IBD diagnoses recorded as primary or secondary diagnosis or any outpatient visits/hospitalisations at gastroenterology clinics.

Healthcare utilisation due to IBD—comprised healthcare utilisation with IBD diagnoses recorded as primary diagnosis.

For inpatient care, both the number of hospitalisations and the number of bed-days were calculated. In accordance with the national standard, bed-days were defined as the date of discharge minus the date of admission plus 1 day.18

2.4. Drug treatment

Data on IBD-related drug utilisation were retrieved from VAL and EHRs.

Drug dispensation data from VAL were used to obtain information on aminosalicylates (sulfasalazine [ATC code: A07EC01], mesalazine [A07EC02], olsalazine [A07EC03], balsalazide [A07EC04]), corticosteroids acting locally (hydrocortisone [A07EA02], budesonide [A07EA06]), oral glucocorticoids (betamethasone [H02AB01], dexamethasone [H02AB02], methylprednisolone [H02AB04], prednisolone [H02AB06], prednisone [H02AB07], hydrocortisone [H02AB09], cortisone [H02AB10]), immunomodulators (azathioprine [L04AX01], mercaptopurine [L01BB02], methotrexate [L04AX03/L01BA01]), and biologicals (infliximab [L04AB02], adalimumab [L04AB04], golimumab [L04AB06]).

Procedure codes [Swedish Classification of Health Interventions]19 were used to identify biologicals administered in the hospital setting. All outpatient specialist visits as well as hospitalisations with procedure code DT016 [intravenous drug administration] followed by the 5-digit ATC code L04AB [tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors] were retrieved.

Furthermore, we extracted data on prescription and administration of biologicals (infliximab [L04AB02], adalimumab [L04AB04], and golimumab [L04AB06]) from the EHRs.

To identify patients actively treated with IBD-related drugs at index date [January 1, 2013] we analysed IBD-related drug utilisation over a 4-month period [September to December 2012] before index, since most patients on continuous drug therapy ought to have their drugs dispensed at least once within a 4-month period. This is due to the Swedish pharmaceutical reimbursement system that allows patients on continuous drug therapy to be dispensed up to a maximum of 3 months’ supply of drugs each time they visit the pharmacy.20

In analyses of exposure to systemic corticosteroids, formulations given orally were included. For comparison, all corticosteroids doses were converted to the equivalent prednisolone dose.21 Exposure to systemic corticosteroids was assessed during January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2013 and the annual dose was calculated. We chose a threshold of > 2000mg of prednisolone to define high corticosteroids users since, according to the therapy tradition in Sweden, this corresponds to two or more corticosteroids courses.

2.5. IBD-related surgery

Data on IBD-related surgery during 2013 were extracted from outpatient specialist and inpatient VAL data. Procedures are coded using the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures.22 For both CD and UC, the following codes were included: JFB, partial excision of intestine; JFG, operations on intestinal stoma or pouch; JFH, total colectomy; and JHD, local operations on anal sphincter. For surgery related to CD, the following codes were also included: JFA60, stricturoplasty in small intestine; JFA63, stricturoplasty in colon; JFA76, closure of fistula of small intestine; and JFA86, closure of fistula of colon. To be classified as a surgery related to IBD, the surgical procedure code had to be followed by a recorded IBD diagnosis.

We also assessed IBD-related drug utilisation during the 4 months preceding the surgery. Since biologicals are a recommended treatment step before surgery, data on biologicals use at any time [data are available from July 1, 2010] before surgery were also analysed. In patients with more than one IBD-related surgery during 2013, drug use was assessed prior to the first surgery recorded.

2.6. Statistical analyses

The exposure in all statistical analyses was disease group [UC, CD, or IBDU], defined during 1997–2012 as described above. Healthcare utilisation, IBD-related drug treatment, and IBD-related surgery were outcomes. Comparisons of healthcare utilisation were performed for all healthcare utilisation, healthcare utilisation related to IBD, and healthcare utilisation due to IBD.

Numbers and proportions were calculated for categorical variables and means, medians, standard deviations [SD], and interquartile ranges were reported for continuous variables. Lorenz curves were generated to assess skewness in healthcare utilisation. We used chi-square testing to analyse differences in drug treatment, healthcare utilisation, and IBD-related surgery between CD and UC patients. Data management and analyses were carried out using SAS 9.4 [SAS Institute, Cary, NC].

2.7. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the regional ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

3. Results

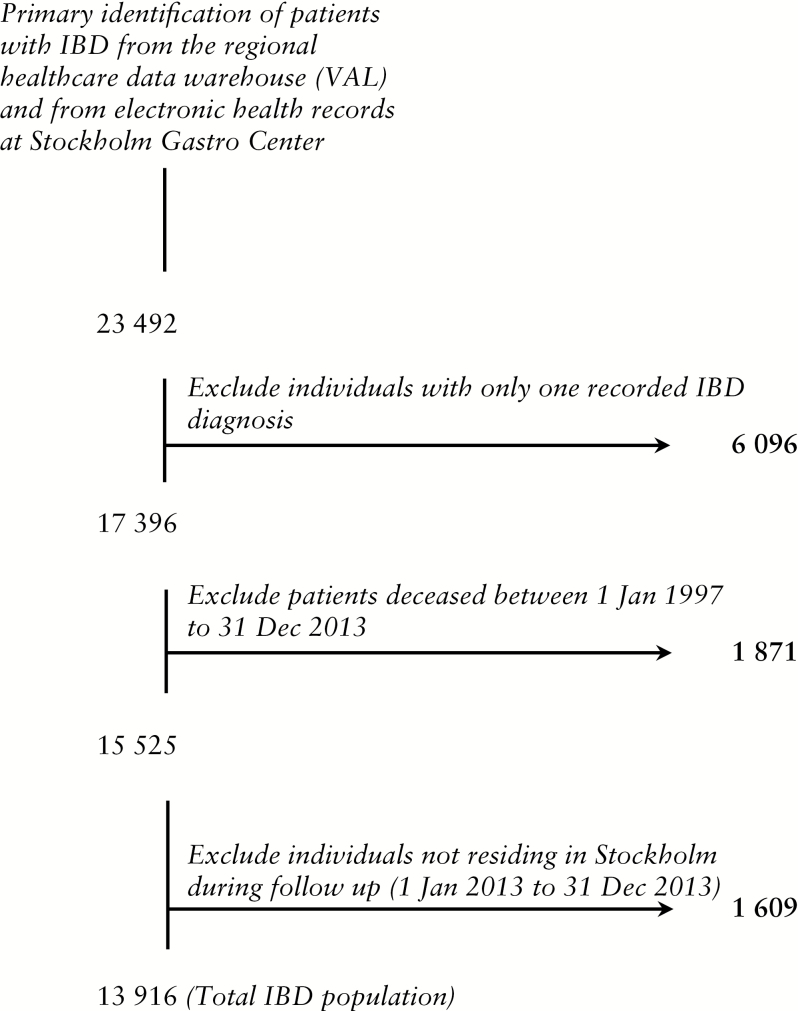

During 1997 to 2012, 23 492 patients with a recorded IBD diagnosis were identified in Stockholm County and 13 916 of these were included in the final analyses [Figure 1]. Given the total population of 2 127 006 in Stockholm County at December 31, 2012, we estimated the prevalence of IBD at 0.65%.

Figure 1.

Identification of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Stockholm County. Flow chart begins with data extracted from the regional healthcare data warehouse [VAL] and from electronic health records at Stockholm Gastro Center.

The mean age for the total IBD population was 49.7 years and 48.9% were women [Table 1]. Most of the patients [73.1%] had a history of IBD for more than 5 years. Crohn’s disease and UC accounted for 40.9% and 53.2% of the population, respectively. The remaining patients [5.9%] either had a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis or were diagnosed with both UC and CD [IBDU].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of IBD patients in Stockholm County.

| IBD population [total] | Crohn’s disease [CD] | Ulcerative colitis [UC] | Inflammatory bowel disease unclassified [IBDU] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n, % | 13 916 [100] | 5690 [40.9] | 7409 [53.2] | 817 [5.9] |

| Sex, % [F/M] | 48.9 / 51.1 | 49.2 / 50.8 | 49.0 / 51.0 | 47.1 / 52.9 |

| Age at 1 Jan 2013 [mean, SD] | 49.7 [17.5] | 48.3 [18.0] | 51.0 [16.8] | 47.7 [19.1] |

| Median [Q1-Q3] | 49 [36–63] | 48 [35–63] | 50 [38–64] | 48 [33–62] |

| Age > 18 years [n, %] | 13605 [97.8] | 5514 [97.0] | 7320 [98.8] | 771 [94.4] |

| Age at first recorded diagnosis [mean, SD]a | 40.2 [16.6] | 38.7 [16.9] | 41.4 [16.0] | 40.1 [18.7] |

| Median [Q1-Q3] | 39 [28–52] | 37 [26–51] | 40 [29–53] | 39 [26–53] |

| Diagnosed within the past 5 years, 2008–2012 [n, %]b | 3736 [26.9] | 1454 [25.6] | 1936 [26.1] | 346 [42.4] |

F/M, female/male; SD, standard deviation; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

aCalculation of age at the patient’s first recorded IBD diagnosis in the regional healthcare data warehouse [VAL] or in electronic medical records from Stockholm Gastro Center. This might indicate the age of IBD onset.

bSince the regional healthcare data warehouse [VAL] only covers patients living in Stockholm County, we might be missing information on the first recorded IBD diagnosis if the patient has migrated to Stockholm County after the onset of IBD. This may lead to an underestimation of calculated disease duration. However, in a sensitivity analysis we found that only 6% of the total IBD population did not reside in the region throughout the whole period of 2008–2012.

3.1. Healthcare utilisation

In total, 91.3% [n = 12 699] of IBD patients had at least one outpatient physician visit or hospitalisation during 2013. Almost 70% of patients were seen by general practitioners but only a few of these visits had a recorded IBD diagnosis. Specialist care has been sought by 81.4% of patients and the majority of these visits were due to IBD-related care [69.2%]. The number of patients requiring at least one hospitalisation during 2013 was 2542 [18.3%] [Table 2].

Table 2.

Healthcare utilisation for inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] patients in Stockholm County during 2013.

| All healthcare utilisation | Healthcare utilisation related to IBD | Healthcare utilisation due to IBD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total IBD pop. [n = 13 916] |

CD [n = 5690] | UC [n = 7409] | IBDU [n = 817] | Total IBD pop. [n = 13 916] |

CD [n = 5690] | UC [n = 7409] | IBDU [n = 817] | Total IBD pop. [n = 13 916] |

CD [n = 5690] | UC [n = 7409] | IBDU [n = 817] | |

| Number of primary care visits [% of patients] | ||||||||||||

| 1–2 | 34.9% | 34.6% | 35.4% | 33.3% | 5.7% | 6.3% | 5.2% | 5.1% | 3.0% | 3.0% | 2.9% | 3.2% |

| 3–5 | 21.4% | 20.5% | 21.7% | 23.5% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.5% | - | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.1% | - |

| 6–10 | 8.9% | 9.4% | 8.5% | 9.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.08% | 0.1% | 0.04% | 0.07% | 0.03% | - |

| ≥ 11 | 4.3% | 4.1% | 4.4% | 5.0% | 0.02% | 0.04% | 0.01% | - | - | - | - | - |

| No visit | 30.5% | 31.4% | 29.9% | 28.9% | 93.6% | 92.7% | 94.2% | 94.8% | 96.8% | 96.6% | 97.0% | 96.8% |

| Number of specialised outpatient care visits [% of patients] | ||||||||||||

| 1–2 | 30.9% | 29.1% | 32.5% | 28.0% | 39.1% | 39.5% | 39.1% | 36.2% | 34.8% | 36.9% | 33.9% | 28.8% |

| 3–5 | 24.3% | 24.6% | 24.1% | 24.5% | 11.6% | 13.7% | 9.8% | 13.7% | 7.6% | 9.8% | 5.9% | 7.1% |

| 6–10 | 16.3% | 18.1% | 14.7% | 18.1% | 4.4% | 6.2% | 3.2% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 4.0% | 1.7% | 2.0% |

| ≥ 11 | 9.9% | 11.6% | 8.4% | 11.3% | 1.2% | 1.8% | 0.7% | 1.5% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.3% | 0.5% |

| No visit | 18.6% | 16.5% | 20.3% | 18.1% | 43.7% | 38.8% | 47.2% | 45.9% | 54.4% | 48.5% | 58.2% | 61.7% |

| Number of hospitalisations [% of patients] | ||||||||||||

| 1–2 | 14.6% | 16.5% | 13.1% | 14.3% | 9.6% | 12.4% | 7.4% | 9.3% | 3.3% | 5.1% | 2.0% | 3.2% |

| 3–5 | 2.8% | 3.3% | 2.2% | 3.7% | 1.6% | 2.2% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.08% | 0.2% |

| 6–10 | 0.7% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.07% | 0.1% | 0.05% | - |

| ≥ 11 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.04% | 0.6% | 0.05% | 0.07% | 0.01% | 0.2% | - | - | - | - |

| No inpatient care | 81.7% | 78.8% | 84.1% | 80.7% | 88.5% | 84.7% | 91.3% | 88.7% | 96.3% | 94.2% | 97.9% | 96.6% |

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBDU, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified.

p < 0.001 for all comparisons on healthcare utilisation between CD and UC except for healthcare utilisation in primary care (all healthcare utilisation [p = 0.086], healthcare utilisation related to IBD [p = 0.004], healthcare utilisation due to IBD [p = 0.16]).

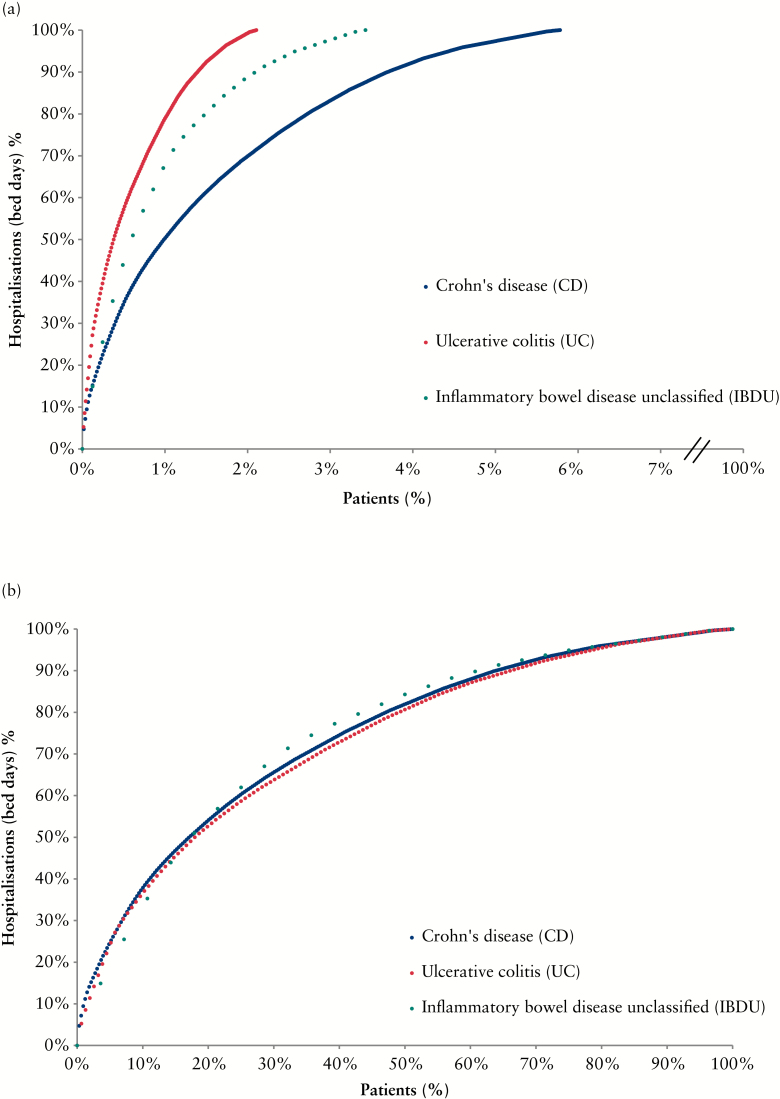

Of the total IBD population, 3.7% [n = 513] accounted for all hospitalisations with IBD recorded as primary discharge diagnosis [Figure 2a]. Of the hospitalised patients, 10% accounted for 37% of the hospitalisations due to IBD [Figure 2b]. Hospitalisations were 2.8 times higher in CD patients compared with UC patients.

Figure 2.

a. Lorenz curves displaying the proportions of inpatient healthcare utilisation during 2013 among all patients in each inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] group (n = 5690 Crohn’s disease [CD], n = 7409 ulcerative colitis [UC], and n = 817 inflammatory bowel disease unclassified [IBDU]). Inpatient healthcare utilisation for IBD was defined by the number of bed-days with IBD listed as primary discharge diagnosis. b. Lorenz curves displaying the proportions of inpatient healthcare utilisation defined by the number of bed-days with IBD listed as primary discharge diagnosis. Only patients who utilised inpatient care during 2013 were included in this Lorenz curve (n = 329 [CD], n = 156 [UC], and n = 28 [IBDU]).

Crohn’s disease patients visited outpatient specialists and were hospitalised more frequently compared with UC patients. The observed difference was found statistically significant [p < 0.0001] for all-cause visits/hospitalisations as well as for IBD-related care and for the care sought due to IBD [ie IBD in primary diagnosis]. In primary care, healthcare utilisation related to IBD [either primary or secondary diagnosis] was significantly higher in CD patients [p = 0.004].

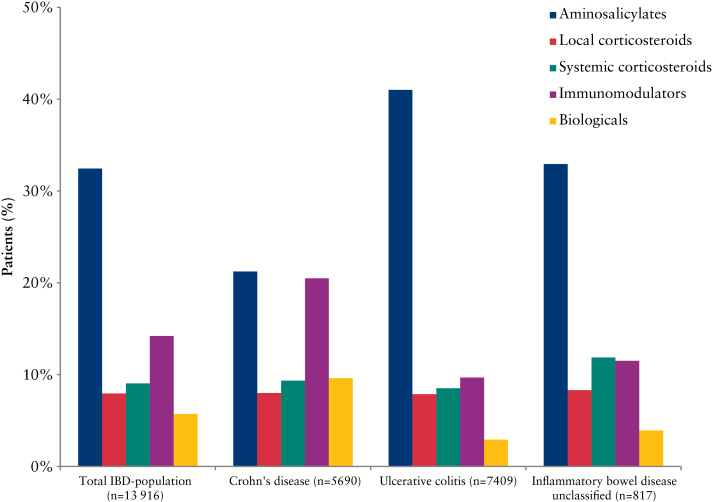

3.2. Drug treatment

A total of 48.9% [n = 6809] of all patients were treated with IBD-related drugs at January 1, 2013 [CD: 48.3%, UC: 49.8%, p = 0.08]. The most common drug therapy was aminosalicylates [32.4%] followed by immunomodulators [14.2%] [Figure 3]. The use of aminosalicylates was more than twice as high in UC [41.0%] compared with CD [21.2%] [p < 0.0001] and use of immunomodulators was more than twice as high in CD [20.5%] compared with UC [9.7%] [p < 0.0001]. Biologicals were used by 5.7% of patients, with higher use among patients with CD [CD: 9.6%, UC: 2.9%, p < 0.0001]. The use of systemic corticosteroids was similar [p = 0.10] across CD and UC. Of all IBD patients, 8.0% were treated with local corticosteroids and 9.1% with systemic corticosteroids. The calculation of annual exposure to systemic corticosteroids identified 506 [3.6%] high corticosteroids users among all IBD patients.

Figure 3.

Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]-related drug treatment at January 1, 2013.

One-third [32.0%] of all IBD patients with current drug therapy were treated with a combination of two or more IBD-related drugs [Table 3]. The most common combination was aminosalicylates and immunomodulators, followed by aminosalicylates and local corticosteroids. Of users of biologicals, 29.0% were treated with these drugs in combination with immunomodulators [CD: 30.7%; UC: 25.3%].

Table 3.

Concomitant IBD-related drug treatment at January 1, 2013.

| IBD related drug treatment | Total IBD population [n = 13 916] |

CD[n = 5690] | UC[n = 7409] | IBDU[n = 817] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminosalicylates | Localcorticosteroids | Systemiccorticosteroids | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | ||||

| Aminosalicylates | 20.42% | 11.88% | 27.22% | 18.12% | ||||

| Immunomodulators | 5.41% | 9.68% | 2.40% | 2.94% | ||||

| Aminosalicylates | Immunomodulators | 3.83% | 3.66% | 3.93% | 4.16% | |||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 2.75% | 3.13% | 2.33% | 3.79% | ||||

| Biologicals | 2.59% | 4.83% | 1.04% | 1.10% | ||||

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | 2.40% | 1.12% | 3.37% | 2.45% | |||

| Local corticosteroids | 2.08% | 2.88% | 1.47% | 2.08% | ||||

| Aminosalicylates | Systemic corticosteroids | 1.86% | 1.27% | 2.13% | 3.55% | |||

| Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | 0.86% | 1.41% | 0.47% | 0.61% | |||

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | 0.78% | 0.35% | 1.09% | 0.98% | ||

| Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.78% | 1.63% | 0.18% | 0.37% | |||

| Aminosalicylates | Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | 0.77% | 0.54% | 0.92% | 0.98% | ||

| Aminosalicylates | Biologicals | 0.59% | 0.56% | 0.63% | 0.37% | |||

| Local corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | 0.57% | 1.05% | 0.20% | 0.61% | |||

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | 0.55% | 0.65% | 0.45% | 0.73% | ||

| Systemic corticosteroids | Biologicals | 0.37% | 0.74% | 0.07% | 0.61% | |||

| Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | 0.37% | 0.47% | 0.30% | 0.24% | |||

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | 0.35% | 0.25% | 0.42% | 0.49% | |

| Aminosalicylates | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.31% | 0.37% | 0.26% | 0.37% | ||

| Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | 0.21% | 0.30% | 0.16% | - | ||

| Local corticosteroids | Biologicals | 0.16% | 0.25% | 0.07% | 0.37% | |||

| Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.16% | 0.32% | 0.05% | - | ||

| Aminosalicylates | Systemic corticosteroids | Biologicals | 0.14% | 0.11% | 0.16% | 0.24% | ||

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | Biologicals | 0.13% | 0.07% | 0.16% | 0.24% | |

| Aminosalicylates | Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.13% | 0.14% | 0.12% | 0.12% | |

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.09% | 0.12% | 0.08% | - |

| Local corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.09% | 0.19% | 0.01% | - | ||

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.06% | 0.09% | 0.04% | 0.12% | |

| Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | Biologicals | 0.04% | 0.05% | 0.04% | - | ||

| Local corticosteroids | Systemic corticosteroids | Immunomodulators | Biologicals | 0.04% | 0.09% | - | - | |

| Aminosalicylates | Local corticosteroids | Biologicals | 0.03% | 0.05% | 0.01% | - | ||

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBDU, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified.

Column cells marked in italic represent monotherapy.

3.3. Surgery

Surgery related to IBD was more common among CD patients compared with UC [p < 0.0001]; 168 [3.0%] patients with CD had an IBD-related surgery during 2013. Among the operated CD patients, the most common dispensed drugs during the 4-month period before the surgery were immunomodulators [26.8%; n = 45], followed by systemic corticosteroids [25.0%; n = 42], and biologicals [23.8%; n = 40]; 65 patients [38.7%] were treated with biologicals at any time before surgery [data are available from July 1, 2010]. Among UC patients, 0.8% [n = 57] underwent IBD-related surgery. Of these, 56.1% [n = 32] were treated with IBD-related drugs during the 4-month period before the surgery. The most common drugs were aminosalicylates used by 40.4% [n = 23]. Biologicals were used by 8.8% [n = 5] during the 4-month period before the surgery and by 40.4% [n = 23] at any time before the surgery.

4. Discussion

This population-based study provides information on healthcare utilisation and drug treatment in all IBD patients residing in Stockholm County. We estimated that the prevalence of IBD in 2013 was 0.65%, which is similar to the results from a recent Swedish nationwide study.2 The prevalence of IBD in Sweden is therefore among the highest in the world23 and is comparable to estimates from Canada, the country with the highest reported IBD incidence and prevalence rates.24

This study indicates that patients with CD are the group with the highest medical needs. Crohn’s disease patients had a higher utilisation of healthcare resources, such as outpatient visits, hospitalisations and surgeries. Crohn’s disease patients were also more frequently treated with immunomodulators and biologicals compared with UC patients.

4.1. Healthcare utilisation

Our data indicate that almost all IBD patients had at least one visit to either primary or secondary care during 2013 and more than half of the population had visits related to IBD. Overall, hospitalisation rates and outpatient visits among IBD patients in Stockholm County appear to be lower than in other countries. In a Canadian study based on data from the Manitoba Health administrative databases,25 the reported number of outpatient visits [mean] was 1380 and 1255 per 100 patients per year for CD and UC, respectively. The corresponding figure from analyses of US inpatient and outpatient insurance claims data was 1030 per 100 patients for CD and 921 per 100 patients for UC.8 We identified 752 and 681 outpatient visits per 100 patients per year for CD and UC, respectively [data not shown]. However, in our data we only included outpatient visits where the patient met a physician. Telephone consultations were not included. When adding all telephone consultations, the mean numbers of consultations increased to 944 and 848 per 100 patients per year for CD and UC, respectively.

Hospital statistics indicate that in Europe, hospitalisation rates vary between 1.2 and 4.3 per 10 000 inhabitants for CD and between 0.7 and 4.7 for UC.26 In 2001 in Canada, hospitalisation rates for CD and UC were 2.7 and 1.3 per 10 000, respectively.27 In the US, the overall hospitalisation rate was 1.8 per 10 000 for CD and 1.1 per 10 000 for UC.28 In our study, the hospitalisation rates for CD and UC were 1.5 and 0.7 per 10 000 inhabitants, respectively.

However, cross-national comparisons on healthcare utilisation must be interpreted with caution both due to the large differences in healthcare organisation and administration and also due to different methodologies and definitions adopted in published studies of healthcare utilisation.

Patients with CD were shown to use more healthcare resources, both outpatient as well as inpatient care. Our findings are in line with previously reported results showing that CD patients consume more services.8,25,29,30 We also observed a highly disproportionate use of hospital services among IBD patients. However, this finding was expected given that in chronic diseases healthcare spending tends to be very skewed.31

4.2. Drug treatment

In our analyses of drug utilisation in IBD patients, we found deviations from the treatment guidelines. The most obvious was the high proportion of patients with CD treated with aminosalicylates in spite of lack of evidence for their efficacy in this indication.4 This finding was communicated to prescribers in Stockholm County.

The usage of corticosteroids is an important marker in the treatment of IBD since a high utilisation might indicate a more aggressive disease course.32 We found that the majority [85%] of IBD population were not treated with corticosteroids, suggesting that a high proportion of patients are in corticosteroid-free remission. However, our findings also showed that 4% of the population were high users of corticosteroids. These patients may instead be considered for a more aggressive maintenance treatment.

Biological therapy in IBD is of special interest as biologicals are an effective treatment option. Biologicals however have some severe adverse effects and also are more expensive compared with other drugs. Therefore, biological therapy is typically given on strict indications and regularly monitored. In our study about 10% and 3% of patients with CD and UC, respectively, were treated with biologicals. The higher proportion of biological therapy for CD has been shown in earlier studies.33,34 Previous studies have also reported a higher use of biologicals for IBD 33,34,35 compared with our findings. These differences are likely explained by different time periods used to assess drug exposure but also by differences in reimbursement systems, local therapy traditions, and how these drugs are prioritised by healthcare authorities. It is also important to acknowledge that there are many other factors influencing the uptake of new medicines in healthcare systems.36,37 In Sweden, there are no direct financial instruments from the authorities regarding prescribing and treatment with biologicals. Furthermore, prescription drugs are provided to patients free of charge once the patient prescription drug expenditure exceeds the threshold of 2200 SEK [approximately €220; www.forex.se].

4.3. IBD-related surgery

A recent analysis of US insurance claims data35 reported an annual rate of IBD-related surgery of 3.3% for CD and 1.6% for UC. Our result for IBD-related surgery for CD is in line with these findings, although we have a lower number for UC. Furthermore, our analyses identified that, of the operated patients with CD, only a quarter used biologicals during the 4 months before surgery. Given that biologicals represent the recommended treatment step before surgery, in some, but not all, cases this might indicate a possible under-use of biologicals. This finding prompted us to carry out an ad hoc manual review of EHRs of patients operated in the three major hospitals in Stockholm [122 CD and 52 UC patients] to investigate the indications for surgery. We found that fistulising disease was the most common indication for surgery in CD patients, and disease refractory to medical therapy was the most common indication for UC patients. An ongoing study involving a thorough review of medical records of IBD patients in Stockholm County will provide further insight to the healthcare that these patients receive.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

We have extracted and linked data from both administrative data sources and EHRs to build a comprehensive overview of healthcare utilisation and drug treatment of IBD. We obtained information on diagnoses from primary care, inpatient, and outpatient specialist care from a large, well-defined region. The study also covered all prescriptions claimed at any pharmacy by IBD patients. Data on biologicals administered in the hospital setting were also extracted, to obtain a complete coverage of drug utilisation in the study population.

This study relies on the accuracy of diagnoses reported in medical records in which some might be missing or misclassified. The diagnostic validity of recorded hospital diagnoses in Sweden in general is high38 although validation studies investigating the accuracy of recording of IBD diagnoses are lacking. In outpatient specialist care and in inpatient care, the primary diagnosis has the highest rank and indicates the reason for the visit or hospitalisation. In primary care, the diagnosis positions are not ranked and therefore calculations of healthcare utilisation related to IBD and healthcare utilisation due to IBD might result in over- or underestimation. We expect, however, that a diagnosis recorded in primary position would likely indicate the main reason for the visit.

Study patients were required to have at least two recorded IBD diagnoses in their health records. This might possibly lead to an underestimation of the number of IBD cases. However, inclusion based on only one recorded IBD diagnosis would likely result in overestimating the number of IBD cases, due to presence of occasional coding errors as well as suspected but eventually unconfirmed IBD cases.

To identify patients actively treated with IBD-related drugs at January 1, 2013, we analysed IBD-related drug utilisation over a 4-month period prior to the index date [September to December 2012]. This will likely cover patients on continuous drug therapy, due to the Swedish pharmaceutical reimbursement system. However, this 4-month period might overestimate the current use of drugs not given on a continuous basis, such as corticosteroids. It is also possible that some combination therapy with IBD-related drugs is overestimated, since patients might terminate their treatment during this time period.

Conclusions

Using population-based data sources that provide information across inpatient and outpatient settings, we described healthcare utilisation and drug treatment in all IBD patients in Stockholm County. This study indicates that patients with CD are the group with the highest medical needs. Twice as many CD patients received immunomodulators compared with UC patients, and CD patients were treated with biologicals three times more often. Crohn’s disease patients had also a higher utilisation of healthcare resources, such as outpatient visits, hospitalisations, and surgeries. These results highlight that CD remains a challenge and further efforts are needed to improve care in these patients.

Funding

This work was part of a programme aimed to explore opportunities for research collaboration between the public healthcare authority in Stockholm County, Sweden, and the pharmaceutical industry. All pharmaceutical companies in Sweden were invited to participate in this programme and, for this project on IBD, AbbVie Sweden AB participated. This project was jointly funded by the Public Healthcare Committee Administration in Stockholm County, Sweden, and AbbVie. AbbVie did not participate in the study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

RL was supported by a scientific grant from Sophiahemmet Foundation. JS is on an advisory board for Itrim [a weight loss programme]. ML received a lecture fee from AbbVie during 2014.

Author Contributions

Study concepts and design: TC, BW, ML, RL, JS, IE. Data management, data analysis, and statistical analysis: TC, IE. Critical revision of the manuscript: TC, BW, ML, RL, JS, IE.

Acknowledgments

Karolinska University Hospital, Södersjukhuset AB, Danderyds Sjukhus AB, and Stockholm Gastro Center are acknowledged for contributing data to this study.

References

- 1. Lakatos PL. Recent trends in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: Up or down? World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:6102–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Busch K, Ludvigsson JF, Ekstrom-Smedby K, et al. Nationwide prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden: A population-based register study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: Current management. J Crohns Colitis 2012;6:991–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, et al. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Current management. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:28–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ford AC, Achkar JP, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in ulcerative colitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:601–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ford AC, Kane SV, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in Crohn’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, Lakatos PL, EpiCom E. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohn’s Colitis 2013;7:322–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kappelman MD, Porter CQ, Galanko JA, et al. Utilisation of healthcare resources by U.S. Children and adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anell A. The public-private pendulum patient choice and equity in Sweden. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M, et al. The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010;106:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jerlvall L, Pehrsson T. Ehälsa i landstingen. [In Swedish.]. [eHealth in Swedish County Councils] 2012. http://www.inera.se/Documents/OM_OSS/Styrdokument_o_rapporter/SLIT-rapporter/eHlsa_i_landstingen_SLIT_2012.pdf Accessed October 9, 2015.

- 12. Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: Possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zarrinkoub R, Wettermark B, Wandell P, et al. The epidemiology of heart failure, based on data for 2.1 million inhabitants in Sweden. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:995–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases [icd-10]. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ Accessed October 9, 2015.

- 15. Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The new Swedish prescribed drug register opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO collaborating centre for drug statistics methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2015. www.whocc.no Accessed October 9, 2015.

- 17. Cars T, Wettermark B, Malmstrom RE, et al. Extraction of electronic health record data in a hospital setting: Comparison of automatic and semi-automatic methods using anti-TNF therapy as model. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2013;112:392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Socialstyrelsen. Norddrg. [In Swedish]. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/norddrg Accessed October 9, 2015.

- 19. Socialstyrelsen. Klassifikation av Vårdåtgärder [KVÅ-2015]. [In Swedish.].] http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/atgardskoderkva Accessed October 9, 2015.

- 20. Sveriges riksdag. Swedish Code of Statuses, ACT 2002: 687, 2§. www.riksdagen.se Accessed October 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordic Centre for Classifications in Health Care. Nomesco Classification of Surgical Procedures. Version 1.16. http://nowbase.org/Publications.aspx Accessed October 9, 2015.

- 23. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54 e42; quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rocchi A, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: A Canadian burden of illness review. Can J Gastroenterol 2012;26:811–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Longobardi T, Bernstein CN. Health care resource utilisation in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:731–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sonnenberg A. Age distribution of IBD hospitalisation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bernstein CN, Nabalamba A. Hospitalisation, surgery, and readmission rates of IBD in Canada: A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nguyen GC, Tuskey A, Dassopoulos T, Harris ML, Brant SR. Rising hospitalisation rates for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States between 1998 and 2004. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:1529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Odes S, Vardi H, Friger M, et al. Cost analysis and cost determinants in a European inflammatory bowel disease inception cohort with 10 years of follow-up evaluation. Gastroenterology 2006;131:719–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vester-Andersen MK, Vind I, Prosberg MV, et al. Hospitalisation, surgical and medical recurrence rates in inflammatory bowel disease 2003-2011 a Danish population-based cohort study. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1675–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ross M. Encyclopedia of Health Services Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Siegel CA, Siegel LS, Hyams JS, et al. Real-time tool to display the predicted disease course and treatment response for children with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:30–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sulz MC, Siebert U, Arvandi M, et al. Predictors for hospitalisation and outpatient visits in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Results from the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;25:790–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burisch J, Vardi H, Pedersen N, et al. Costs and resource utilisation for diagnosis and treatment during the initial year in a European inflammatory bowel disease inception cohort: An ECCO-EPICOM study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Deen WK, van Oijen MG, Myers KD, et al. A nationwide 2010–2012 analysis of U.S. health care utilisation in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1747–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lubloy A. Factors affecting the uptake of new medicines: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chauhan D, Mason A. Factors affecting the uptake of new medicines in secondary care a literature review. J Clin Pharm Ther 2008;33:339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]