Abstract

Background and Aims:

Galectin-3 [Gal-3] is an endogenous lectin with a broad spectrum of immunoregulatory effects: it plays an important role in autoimmune/inflammatory and malignant diseases, but the precise role of Gal-3 in pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis is still unknown.

Methods:

We used a model of dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-induced acute colitis. The role of Gal-3 in pathogenesis of this disease was tested by evaluating disease development in Gal-3 deficient mice and administration of Gal-3 inhibitor. Disease was monitored by clinical, histological, histochemical, and immunophenotypic investigations. Adoptive transfer was used to detect cellular events in pathogenesis.

Results:

Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of Gal-3 significantly attenuate DSS-induced colitis. Gal-3 deletion suppresses production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in colonic macrophages and favours their alternative activation, as well as significantly reducing activation of NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 [NLRP3] inflammasome in macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages isolated from untreated Gal-3-/- mice and treated in vitro with bacterial lipopolysaccharide or DSS produce lower amounts of tumour necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α] and interleukin beta [IL-1β] when compared with wild type [WT] cells. Genetic deletion of Gal-3 did not directly affect total neutrophils, inflammatory dendritic cells [DCs] or natural killer [NK] T cells. However, the total number of CD11c+ CD80+ DCs which produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as TNF-α and IL-1β producing CD45+ CD11c- Ly6G+ neutrophils were significantly lower in colons of Gal-3-/- DSS-treated mice. Adoptive transfer of WT macrophages significantly enhanced the severity of disease in Gal-3-/- mice.

Conclusions:

Gal-3 expression promotes acute DSS-induced colitis and plays an important pro-inflammatory role in the induction phase of colitis by promoting the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β in macrophages.

Keywords: Gal-3, DSS colitis, NLRP3

1. Introduction

Galectin-3 [Gal-3] is an endogenous lectin with a broad spectrum of immunoregulatory effects: it plays an important disease-exacerbating role in autoimmune/inflammatory and malignant diseases,1,2,3,4,5,6 but has protective role in obesity-induced inflammation and type 2 diabetes.7 Recently, clinical studies suggested a role for Gal-3 in ulcerative colitis [UC].8,9,10 Serum concentrations of Gal-3 were significantly increased in specimens of patients with active and remission-stage UC.8,9,10 In UC patients, Gal-3 was produced by monocytes9 and expressed on CD68+ colon-infiltrating macrophages.10 However, the precise role of Gal-3 in pathogenesis of UC is still unknown.

Because of the high degree of uniformity and reproducibility, as well as some similarities to human colitis, dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-induced colitis has been used to elucidate molecular and cellular pathways involved in pathogenesis of acute colitis.11 DSS-induced colitis has been considered to be driven by macrophages which produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, cause tissue damage, and induce migration of neutrophils, dendritic cells [DCs], natural killer [NK] and NK T cells, mast cells and eosinophils in the colon.12 Effector cells of acquired immunity are not involved in acute colitis, as disease occurs in T and B cell-deficient mice.13

Since Gal-3 is involved in migration and function of innate immune cells,14,15,16 we used DSS-induced colitis to evaluate the role of Gal-3 in the pathogenesis of acute colitis. Here we provide the first evidence that genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of Gal-3 leads to a marked attenuation of DSS-induced colitis due to reduced activation of NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 [NLRP3] inflammasome and attenuated production of interleukin beta [IL-1β] in macrophages. Our data indicate that Gal-3 plays an important pro-inflammatory role in DSS-induced colitis and may be a potential target for therapeutic intervention in intestinal inflammatory disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

Patients with clinically and histologically proven diagnosis of UC [n = 10] and non-UC controls [n = 10] [patients with negative histological findings, who underwent colonoscopy because of colon cancer screening or abdominal problems] were included in this study.

In each individual case, the diagnosis and assessment of the severity of UC was confirmed by standard colonoscopy, histological criteria, and disease activity, as previously described.8,9,10

All patients gave their informed consent for blood and tissue analysis, and the study has been approved by the local ethics committee of Clinical Center Kragujevac, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac. Patients were under continuous medical supervision at the Clinical Center Kragujevac, Faculty of Medical Sciences University of Kragujevac.

2.2. Expression of Gal-3 on colon infiltrating macrophages and its correlation with expression of inflammatory cytokines

Biopsy samples were obtained by colonoscopy from patients with acute UC and from non-UC controls. The expression of Gal-3, CD68, and IL-1β was determined by immunohistochemistry [IHC], as previously described.17 For that purpose, DAKO-labelled streptavidin biotin [LSAB] + system peroxidase [DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA, USA] kit, anti-mouse Gal-3 (ab7278 [9C4], 1:100; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-mouse CD68 (ab49777 [514H12] 1:40; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), and anti-rabbit IL-1β [ab9722 1:100; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA] antibodies were used. The counting was performed under standard light microscope. Expression of Gal-3, CD68, and IL-1β in colon tissue for each section was counted by using 400x magnification in five selected areas with highest density infiltration. The number of positive inflammatory cells in mucosa is presented as percentage. The average percentage of positive cells per high-power field was determined by two independent pathologists without previous information about the patient’s clinical data.

2.3. In vitro stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMNCs] were prepared as previously described.9 PBMNCs were isolated from UC patients and non-UC controls, plated in a 24-well plate [1×106 cells per well] and primed with 10ng/ml LPS [lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli L2880, Sigma Aldrich] in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/l L-glutamine, 1 mmol/l penicillin-streptomycin, and 1 mmol/l mixed non-essential amino acids [Sigma, USA] at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a fully humidified atmosphere for 48h, as suggested.7

2.4. Flow cytometry analysis of PBMNCs

Expression of Gal-3 on PBMNCs was analysed by flow cytometry [FACS], as described.1

2.5. Animals

Male, 6-8-week-old wild type [WT] and Gal-3-/- C57BL/6 mice [provided by Dr Daniel Hsu, University of California, Sacramento, CA] were used for the induction of DSS-induced colitis. Targeted disruption of mouse Gal-3 gene was performed in C57BL/6 embryonic stem cells and mice homozygous for the disrupted gene were obtained.18 Breeding pairs of Gal-3-/- and WT Gal-3+/+ C57BL/6 mice of the same substrain were maintained in animal facilities of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Serbia. All animals received humane care and all experiments were approved by and conducted in accordance with, the Guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Serbia. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with a 12-h light-dark cycle and were administered standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum.

2.6. Induction of acute colitis

DSS [3%, molecular weight 40kDa; TdB Consultancy, Uppsala, Sweden] was given to mice in place of normal drinking water for up to 7 days.19 Control mice had access to DSS-free water.

2.7. Pharmacological inhibition of Gal-3

WT mice were treated with inhibitor of galectin-3 [GM-CT-01; 100 μg on Days 0, 2, 4, and 6, intraperitoneally], kindly provided by Dr Anatole Klyosov.20

2.8. Assessment of the severity of colitis

Disease Activity Index [DAI] was used to assess the clinical signs of colitis.21 Body weight measurements, analysis of stool consistency, and faecal occult blood tests were performed daily.21

2.9. Histology

For histological analysis, colons were removed from euthanised mice, rinsed with phosphate buffer solution [PBS], and cut longitudinally before being rolled into ‘Swiss roll’, as previously described.22 Swiss-rolled colons were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were stained with haematoxylin-eosin [H&E], and examined in a blinded manner by a pathologist. Sections were analysed for damage to epithelium including damage to crypts, submucosal oedema, haemorrhage, and infiltration by immune cells. The histology score for each mouse was calculated as the sum of ‘Infiltration’ and ‘Damage of Epithelium’ sub-scores, as previously described.23

2.10. Measurement of cytokines in serum of DSS-treated animals

The commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] sets [R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN] were used to determine the concentration of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, transforming growth factor beta [TGF-β], and IL-10, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.11. Expression of Gal-3, IL-1β, and NLRP3 in DSS-injured colons

The expression of Gal-3, IL-1β, and NLRP3 was assessed using immunostaining, as described.17 Mouse intestinal sections were routinely fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde, dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in xylene, and subsequently embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissue samples were sectioned at 4–5 μm and tissue sections deparaffinised by two washes in xylene for 10min, and rehydrated in series of 100%, 96%, 70%, and 50% alcohol solutions. Immunohistochemical staining was performed by the streptavidin-biotin method. Briefly, sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity and then microwaved for 20min in 10 mmol/l sodium citrate [pH 6.0]. The sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Gal-3 [1:100 dilution; ab53082], IL-1β [1:50 dilution; ab9722], and NLRP3 [1:100 dilution; ab91525] for 60min. After the incubation with primary antibodies, biotinylated secondary antibodies were applied, followed by detection using the AEC [rabbit-specific HRP-AEC detection IHC kit, ab94361] method. AEC [3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole] was used as the chromogen. Counterstaining was performed with haematoxylin.

2.12. Real time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reation analysis

Messenger RNA [mRNA] analysis for NLRP3 and IL-1β was performed as described.24 In order to prevent the inhibitory effect of DSS on the reverse transcriptase activity, we used the established protocol.25 Total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent [Invitrogen, Paisley, UK] according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 1mg of RNA was used in the reverse transcription reaction using M-MuLV reverse trascriptase and random hexamers [Fermentas, Vilnus, Lithuania] according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] was performed in a 96-well reaction plate [MicroAmp Optical, Foster City, CA] in a Realplex Mastercycler [Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany]. The reactions were prepared according to the standard protocol for one-step QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR [Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK], using commercially available primers for Gal-3, NLRP3, and IL-1β. For the detection of IL-10 and TGF-β, TaqMan Master Mix and the following TaqMan primers and probes from Life Technologies [Carlsbad, CA] were used: IL-10 [Mm00439614_m1] and TGF-β [Mm01178820_m1].

2.13. Flow cytometry analysis of colon infiltrating cells

Isolation of immune cells from lamina propria and flow cytometry analysis were conducted as previously described.26 Briefly, each colon was dissected away from caecum. The colons were cut in pieces 3cm long and then cut longitudinally, so that 3 x 3–cm flaps of colonic tissue were made. The flaps were placed in a 50-ml conical tube and washed three to five times with 30ml cold HBSS, calcium and magnesium free. After decanting the supernatant, the pieces were incubated in 20ml HBSS/EDTA for 30min in a 37°C water bath. Each tube was shaken regularly during the incubation to ensure that epithelial cells were disrupted from the mucosa. The pieces were sedimented and the supernatant was decanted. The remaining EDTA were washed out with 40ml HBSS, calcium and magnesium free. The fragments of colonic tissue were placed in a 10-cm Petri dish and cut into smaller pieces with a scalpel. The pieces were aspirated with a pipette, transferred to a fresh 50-ml conical tube and filled to 20ml with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium [DMEM] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS]. Then, 1ml of 4000 Mandl units [3 x 106 Wünsch units]/ml collagenase D and 200 µl of 1mg/ml DNase were added to the tube and incubated for 1h in a 37° C water bath. The supernatant was filtered through a 100-µm nylon cell strainer into a clean 50-ml conical tube. Cold HBSS, calcium and magnesium free, was added to 50ml. Cells were pelleted by centrifuging 10min at 450g, at 4°C. The pellet was disrupted and cells were re-suspended in 50ml HBSS, calcium and magnesium free, and filtered through a 40-µm nylon cell strainer into a clean 50-ml conical tube. Cells were again pelleted by centrifuging 10min at 450g, at 4°C. The pellet was disrupted and cells were re-suspended in 20ml of 30% Percoll. Then, the cell suspension was carefully layered over 25ml of 70% Percoll in a 50-ml conical tube and centrifuged for 20min at 1100 x g, room temperature, with as low an acceleration rate as possible and with the brake off. Clumping of cells was prevented by the addition of 1mM EDTA to the solution. Epithelial cells floated on the 30% Percoll layer, and immune cells were found between the 30% and 70% layers. Debris and dead cells were pelleted at the bottom of the conical tube.

Flow cytometry followed routine procedures by using 1 x 106 cells per sample, and were incubated with anti-mouse F4/80, CD11b, CD206, I-A, CD11c, CD80, CD8, CD45, CD117, FcεRI, CD3, and Gal-3 conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ], phycoerythrin [PE; BD Biosciences], peridinin chlorophyll protein [BD Biosciences], or allophycocyanin [APC; BD Biosciences]. For the intracellular staining, cells were previously stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate [PMA] and ionomycin for 4h at 37°C with the addition of 1 μg/ml Golgi plug. Following extracellular staining, cells were fixed, permeabilised, and stained for IL-6, IL-12, IL-1β, IL-10, and TNF-α conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ], phycoerythrin [PE; BD Biosciences], peridinin chlorophyll protein [BD Biosciences], or allophycocyanin [APC; BD Biosciences]. Flow cytometric analysis was conducted on a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur and analysed by using the WinMDI software analysis program.

2.14. Isolation and in vitro stimulation of peritoneal macrophages

Macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity of untreated, healthy WT and Gal3-/- mice, plated at a density of 106 cells/well, primed with 10ng/ml LPS for 2h, and incubated with 3% DSS for 24h, as described.27 The levels of TNF-α and IL-1β were determined in macrophages by flow cytometry and in cell culture supernatants by ELISA sets, according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

2.15. Adoptive transfer of peritoneal macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages isolated from untreated, healthy WT and Gal3-/- mice, were intravenously transferred [1 x 106] into Gal3-/- recipients at Days -1 and +1 of DSS treatment, as suggested.28

2.16. In vivo depletion of macrophages

Clodronate-containing liposomes [standard macrophage depletion kit; Encapsula NanoSciences LLC] were intraperitoneally [i.p.] injected 4 days before onset of DSS colitis, to ensure depletion of resident macrophages, and every 2 days of DSS treatment, to deplete new infiltrating macrophages.29

2.17. Adoptive transfer of peritoneal neutrophils

Neutrophils were harvested from the peritoneum of healthy WT and Gal3-/- mice, 8h after i.p. injection of 3% thioglycollate, 30 purified by magnetic cell sorting, and transferred [i.p. 2 x 106 cells per mouse] into Gal3-/- recipients at Day 4 of DSS treatment, as previously described.31

2.18. Isolation of DCs and adoptive transfer of DCs

DCs were isolated from spleen of healthy WT and Gal-3-/- mice by magnetic cell sorting. Single-cell suspensions of mononuclear cells derived from the spleen were labelled with CD11c MicroBeads [Miltenyi Biotec]. The labelled cells were subsequently positively selected using MACS Column [Miltenyi Biotec] and MACS Separator [Miltenyi Biotec]. Isolated DCs were then used in the adoptive transfer experiments.

For adoptive transfer-based experiments, healthy WT and Gal-3-/- DCs [2 x 1 05 cells per mouse] were transferred i.p. into DSS-treated Gal-3-/- recipients on the fifth day of DSS administration, as suggested.32

2.19. In vivo activation of NKT cells

In order to test the effect of genetic deletion of Gal-3 on the protective function of NKT cells in DSS-induced colitis,33 a specific and potent activator of NKT cells, α-galactoceramide [α-GalCer], was injected [100 μg/kg body weight, i.p. every day of the experiment] in DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- mice.34

2.20. Statistics

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] for each group. Results were analysed by Student’s t test. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to test the correlations between two variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 for Windows software [SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL]. The difference was considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Gal-3 is highly expressed in the colons of patients with ulcerative colitis

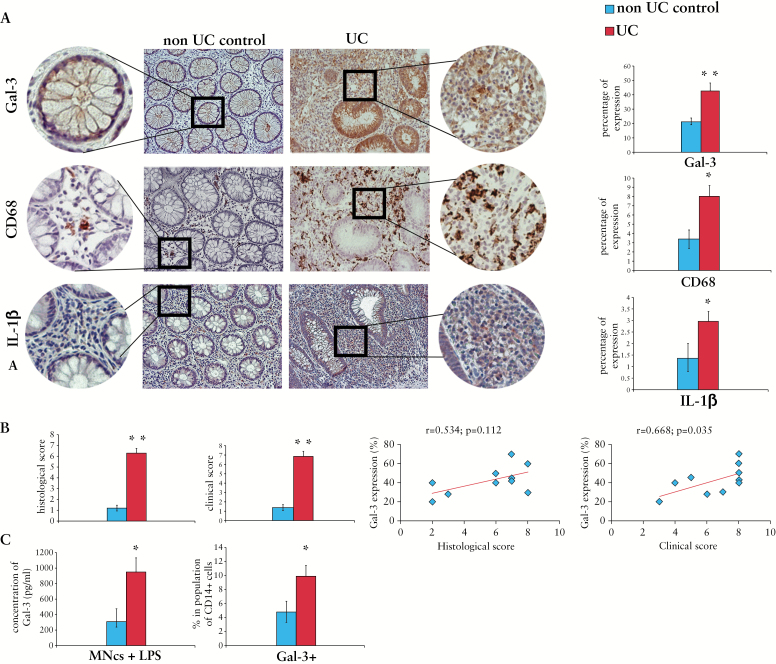

Compared with non UC controls, Gal-3 was highly expressed in the colons of patients suffering from UC [Figure 1A]. In addition, the expression of Gal-3 correlated with clinical and histological scores [Figure 1B].

Figure 1.

Galectin-3 [Gal-3] is highly expressed in the colons of patients with ulcerative colitis. Representative/adjacent paraffin sections of non-ulcerative colitis [UC] controls and UC patients staining for Gal-3 and CD68 [A]. Original magnification 200x. Histological and clinical scores of non UC controls and UC patients; correlation between Gal-3 expression and histological and clinical scores [B]. Concentration of Gal-3 in supernatants of lipopolysaccharide [LPS]-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMNCs]. The percentage of Gal-3+ cells in population of CD14+ cells [C].

Immunohistochemical staining revealed strong association between expression of Gal-3, CD68, and IL-1β, indicating the importance of Gal-3 for macrophage activation in the colon [Figure 1A]. Only few CD68+ cells were noticed in the lamina propria of non-UC controls and Gal-3 was mainly expressed on crypt epithelium. In contrast, there was intense Gal-3 staining both in the epithelium and in the lamina propria of UC patients [Figure 1A]. Strong expression of CD68 and Gal-3 noticed on the majority of lamina propria-infiltrating mononuclear cells of UC patients suggests an involvement of Gal-3 in macrophage-dependent colonic inflammation.

In vitro LPS-stimulated PBMNCs obtained from UC patients produced significantly more Gal-3 than healthy controls [Figure 1C], and the percentage of PBMNCs that express CD14 and Gal-3 was significantly higher in UC patients, indicating the importance of Gal-3 for LPS-dependent activation of macrophages [Figure 1C].

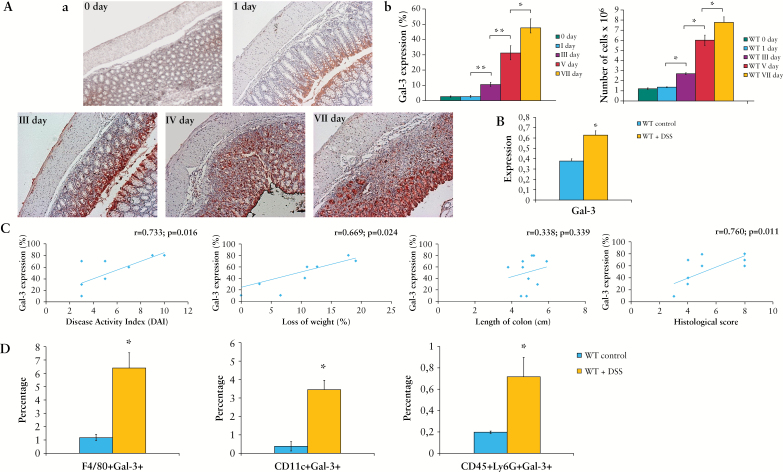

3.2. Expression of Gal-3 in the colon tissue is associated with a progression of DSS-induced colitis and infiltration of immune cells in mice

There was an increased expression of Gal-3 in the colon of C57BL/6 mice during the progression of DSS-induced colitis [Figure 2A, B]. The expression of Gal-3 correlated with disease activity index and histological score and was associated with the influx of immune cells in diseased colon tissue [Figure 2C]. Gal-3 was expressed on lamina propria-infiltrating F4/80+ macrophages, CD11c+ DCs, as well as CD45+Ly6G+ neutrophils that were present in significantly higher numbers in colons of DSS-treated mice compared with control animals [Figure 2D].

Figure 2.

Expression of Galectin-3 [Gal-3] in colon is associated with a progression of dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-induced colitis and infiltration of immune cells. Expression of Gal-3 in colon of WT mice during a progression of DSS-induced colitis [A-a]. Percentage of expression and influx of inflammatory cells in colons of wild type [WT] treated mice during DSS treatment [A-b]. Polymerase chain reaction [PCR] detection of Gal-3 in colon tissue of WT DSS-treated mice [B]. Correlation between expression of Gal-3 and Disease Activity Index [DAI], loss of weight, length of colon, and histological score [C]. Percentage of Gal-3 expressing immune cells [D]. Data presented as mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 10 mice per experimental groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

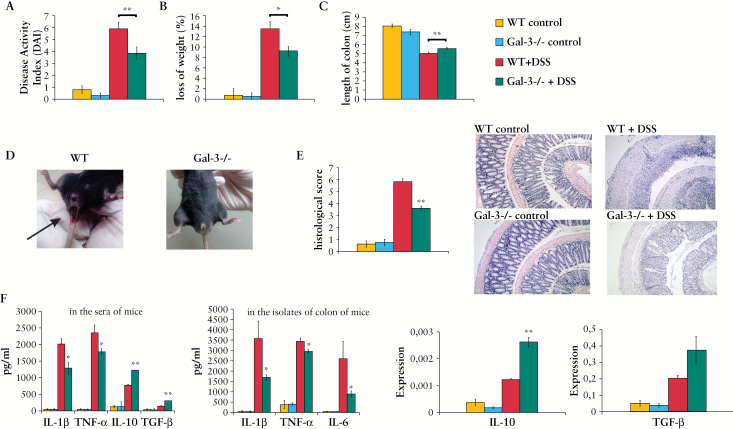

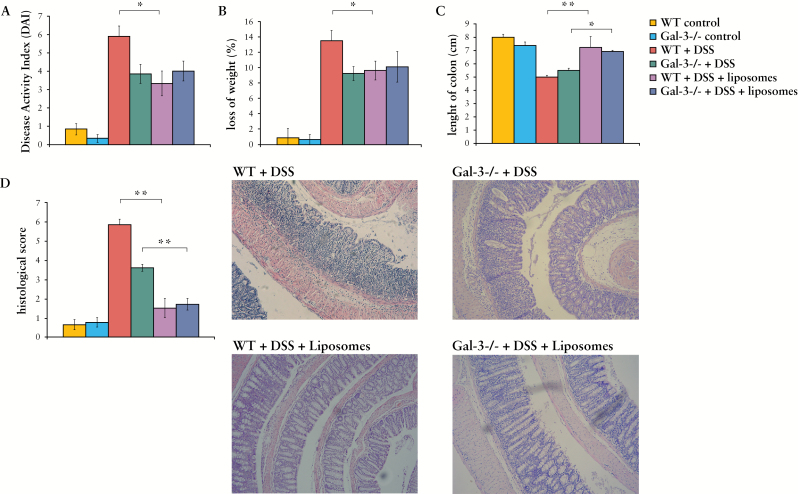

3.3. Genetic deletion of Gal-3 attenuates DSS- induced colitis

All of DSS-treated WT mice developed severe colitis with similar clinical symptoms. The presence of blood in the faeces was detected 1 or 2 days after the start of DSS treatment, whereas gross bleeding and diarrhoea were observed from Day 4. Body weight loss [> 5%] became prominent after 4 days of DSS treatment. The DAI score, body weight loss, and colon shortening were significantly lower in DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice when compared with WT DSS-treated animals [Figure 3A-D].

Figure 3.

Genetic deletion of Galectin-3 [Gal-3] attenuates dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-induced colitis. Water with 3% DSS was given to mice for 7 days; regular drinking water was fed to control mice. Disease Activity Index [DAI] scored at Day 7 using the following parameters: weight loss, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding [A, B, D]. After DSS treatment, the length of the entire colon was measured [C]. Histological examination was performed with haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining [E]. H&E staining images of representative colon tissues are shown at the same magnifications [100x] [E]. Concentration of serum and colon cytokines [F]. Data presented as mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 10 mice per experimental groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Histological analysis of WT mice revealed that 7 days of DSS treatment caused severe inflammation and an almost complete ulceration of colons. Severe inflammation was manifested by significant epithelial cell damage, oedema, ulceration, extensive crypt drop-out and massive infiltration of immune cells [Figure 3E]. In contrast, the colon architecture in similarly treated Gal-3-/- mice appeared relatively normal, showing only mild evidence of crypt distortion, widening, and inflammation [Figure 3E].

3.4. DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice have lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α in serum and colon tissue

Level of pro-inflammatory cytokines [IL-1β and TNF-α] were significantly lower in sera and colons [IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6] of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice when compared with WT DSS-treated mice [Figure 3F]. Conversely, there were significantly higher levels of TGF-β and anti-inflammatory IL-10 in sera and higher expression of IL-10 mRNA in colons of Gal-3-/- mice when compared with WT DSS-treated mice [Figure 3F].

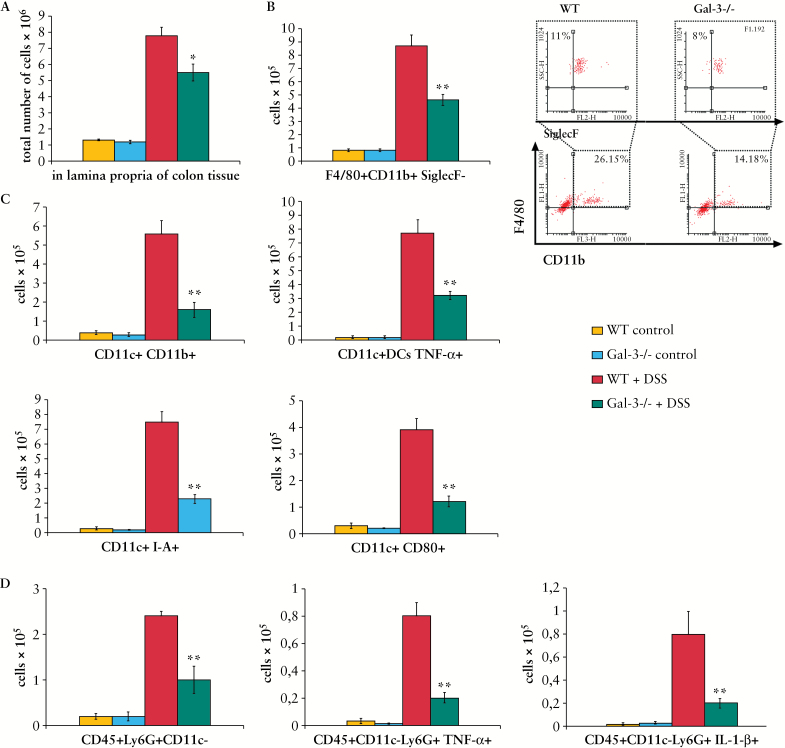

3.5. Genetic deletion of Gal-3 results in markedly reduced number of macrophages, inflammatory DCs, and neutrophils in colons of DSS-treated mice

There were significantly lower numbers of colon-infiltrating immune cells in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice when compared with similarly treated WT animals [Figure 4A]. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the total numbers of colonic macrophages [F4/80+CD11b+SiglecF-], inflammatory DCs [CD11c+CD11b+], TNF-α producing, I-A-and CD80-expressing DCs, as well as TNF-α and IL-1β producing neutrophils [CD45+Ly6G+CD11c-] were lower in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice [Figure 4B-D, p< 0.001].

Figure 4.

Genetic deletion of Galectin-3 [Gal-3] results in markedly reduced number of inflammatory cells in colons of dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-treated mice. The total number of immune cells in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice was higher when compared with similarly treated wild type [WT] animals [A]. The total number of F4/80+CD11b+SiglecF- macrophages is shown as well as representative flow cytometry dot plots [B]. Inflammatory CD11c+CD11b+ DCs, tumour necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α] producing dendritic cells [DCs], as well as DCs expressing I-A and co-stimulatory CD80, were significantly lower in colons of Gal-3-/- DSS treated mice [C]. The total numbers of TNF-α and interkeukin-1 beta [IL-1β] producing CD45+Ly6G+CD11c- neutrophils were lower in colons of Gal-3-/- DSS treated mice [D]. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] [n = 10 per group]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

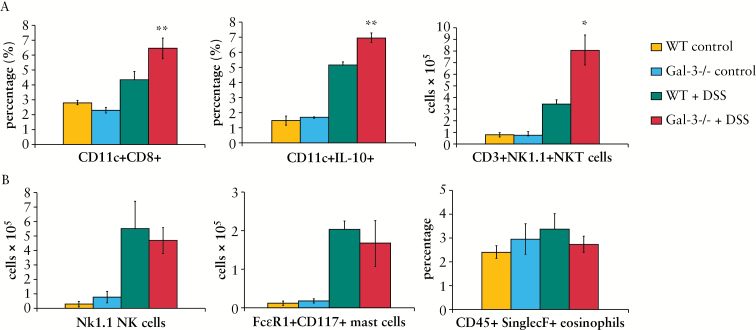

The percentage of regulatory DCs [CD11c+CD8+] and IL-10 producing DCs [p < 0.001] as well as the total number of protective NKT cells [CD3+NK1.1+] were significantly higher in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice [p < 0.05] [Figure 5A]. There was no significant difference in total number of NK cells [NK1.1+CD3-], mast cells [CD117+FcERI+], or eosinophils [CD45+SinglecF+] between the experimental groups [Figure 5B].

Figure 5.

Genetic deletion of Galectin-3 [Gal-3] enhances number of regulatory dendritic cells [DCs] in colons of dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-treated mice. The percentage of regulatory DCs [CD11c+CD8+] and interleukin-10 [IL-10] producing DCs [p < 0.001], as well as the total number of protective CD3+NK1.1+NKT cells, was significantly higher in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice [A]. The number of NK1.1+CD3- NK cells, CD117+FcERI+ mast cells and percentage of CD45+SinglecF+ eosinophils is shown [B]. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] [n = 10 per group]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

3.6. Genetic deletion of Gal-3 did not directly affect function of neutrophils, DCs, or NKT cells

Although it is well known that Gal-3 has an important role in neutrophil function,6 adoptive transfer of peritoneal neutrophils isolated from either WT or Gal-3-/- mice did not enhance severity of DSS-induced colitis in Gal-3-/- animals [see Supplementary Figure 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

Since we recently showed that Gal-3 regulates the cross-talk between DCs and NKT cells in the liver, 17 and we noticed significant difference in the number of DCs and NKT cells in colons of DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- mice [Figures 4C, 5A], we analysed whether genetic deletion of Gal-3 affects the function of colonic DCs and NKT cells.

Adoptive transfer of both WT and Gal-3-/- DCs did not significantly aggravate severity of DSS-induced colitis in Gal-3-/- mice [see Supplementary Figure 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. Injection of α-GalCer, specific and potent activator of NKT cells, significantly attenuated DSS-induced colitis in both WT and Gal-3-/- mice, as evaluated by clinical and histology scores [see Supplementary Figure 3A-D, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online ]. In addition, administration of α-GalCer significantly elevated the percentage of protective IL-10 producing NKT in colons of both DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- mice [see Supplementary Figure 3E].

Thus, it appears that α-GalCer induced NKT cells have a protective effect in DSS-induced colitis, both in WT and in Gal-3-/- mice. The difference between disease activity index [DSS-treated only] and α-GalCer treated animals remains statistically significant in both WT and Gal-3-/- mice [see Supplementary Figure 3].

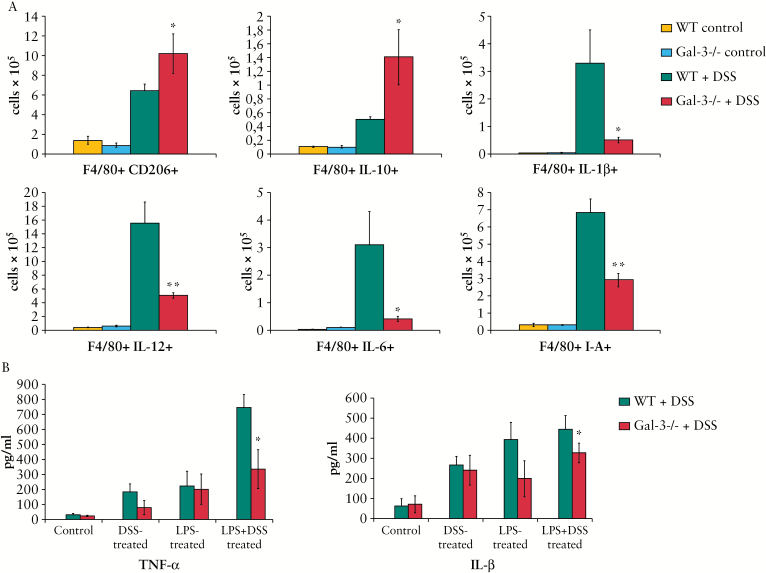

3.7. Gal-3 deletion attenuated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages and favoured their alternative activation

Intracellular staining showed that there were significantly higher numbers of F4/80+CD206+ and IL-10 producing alternatively activated M2 macrophages and significantly reduced numbers of IL-1β-, IL-12 and IL-6 producing inflammatory F4/80+CD11b+I-A+ macrophages in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice compared with similarly treated WT animals [Figure 6A].

Figure 6.

Galectin-3 [Gal-3] deletion favoured macrophages alternative activation. The number of F4/80+CD206+ and interleukin-10 [IL-10] producing alternatively activated M2 macrophages [A]. After 7 days of dextran sulphate sodium [DSS] treatment there was significantly reduced number of IL-1β-, IL-12 and IL-6 producing inflammatory F4/80+CD11b+I-A+ macrophages in colons of Gal-3-/- mice compared with wild type [WT] animals [A]. In vitro lipopolysaccharide [LPS]- and DSS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages isolated from healthy Gal-3-/- mice produce lower amounts of tumour necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α] and interleukin-1 beta [IL-1β] when compared with peritoneal macrophages isolated from healthy WT animals [B]. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] [n = 10 per group]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

In order to establish the inherent capacity of WT and Gal-3-/- macrophages to respond to specific [DSS] and general [LPS] stimuli, macrophages were isolated from untreated, healthy WT and Gal-3-/- animals and in vitro stimulated by LPS and DSS. In vitro LPS- and DSS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages isolated from untreated Gal-3-/- mice produced lower amounts of TNF-α and IL-1β when compared with peritoneal macrophages isolated from healthy WT animals [Figure 6B].

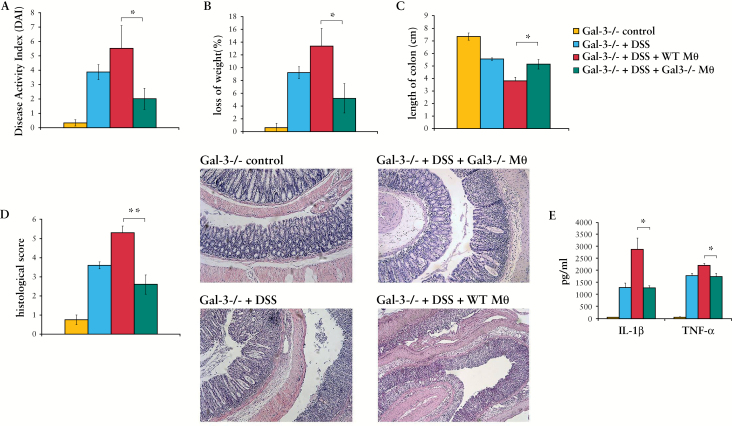

3.8. Gal-3 deletion attenuates macrophage capacity to induce colon damage

In order to determine whether the difference in phenotype and function of WT and Gal-3-/- macrophages is crucial for attenuated DSS-induced colitis in Gal-3-/- mice, adoptive transfer experiments were done. Adoptive transfer of WT macrophages significantly enhanced the severity of DSS-induced colitis in Gal-3-/- mice [Figure 7A-D], as evaluated by clinical and histological parameters. Adoptive transfer of WT macrophages in DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice resulted in significant increase in DAI score, body weight loss, colon shortening, gross bleeding, and diarrhoea. As shown in Figure 7, the transfer of WT macrophages in comparison with Gal-3-/- macrophages significantly enhanced disease activity index [Figure 7A]. This is the best illustrated in histological slides [Figure 7D] showing massive destruction of crypts in Gal-3-/- mice injected with WT macrophages [lower panel] compared with almost normal colon architecture seen in mice injected with Gal-3-/- macrophages [upper panel], occurring in parallel with an emerging inflammatory response and elevated serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α [Figure 7E].

Figure 7.

Adoptive transfer of macrophages worsens acute dextran sulphate sodium [DSS] colitis. Adoptive transfer of macrophages resulted in a significant increase in colitis severity. Body weight was measured daily during DSS treatment. After 7 days, Disease Activity Index [DAI] was evaluated and colon length was measured [A-C]. Histological scores were determined and representative haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] paraffin sections [Swiss-roll cut] of mouse colon are shown [D]. Level of pro-inflammatory (interleukin-1 beta [IL-1β] and tumour necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) cytokines were significantly lower in sera of Galectin-3 [Gal-3]-/- DSS-treated mice compared with wild type [WT] animals DSS treated [E]. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] [n = 10 per group]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

3.9. Macrophage depletion diminished the differences in severity of DSS-induced colitis between WT and Gal-3-/- mice

In order to clarify whether macrophage depletion affects the difference between DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- mice, clodronate-containing liposomes were initially injected intraperitoneally 4 days before DSS administration and continued every second day [0, 2, 4, 6] of the protocol. Macrophage depletion significantly attenuated DSS-induced colitis in WT as evaluated by clinical and histological scores. Most importantly, macrophage depletion diminished the differences between DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- mice. There were no significant differences in DAI score, body weight loss, or colon shortening between DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- mice after injection of clodronate-containing liposomes [Figure 8A-C]. Histological analysis confirmed these findings, showing no significant differences in colon architecture between DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- mice that received clodronate-containing liposomes. All colons appeared relatively normal, showing only mild evidence of crypt distortion, widening, and inflammation [Figure 8D].

Figure 8.

Depletion of macrophages suppress acute colitis. Depletion of macrophages showed reduced clinical and histological scores between dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-treated groups [A-D]. Representative haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] paraffin sections are shown [D]. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] [n = 10 per group]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

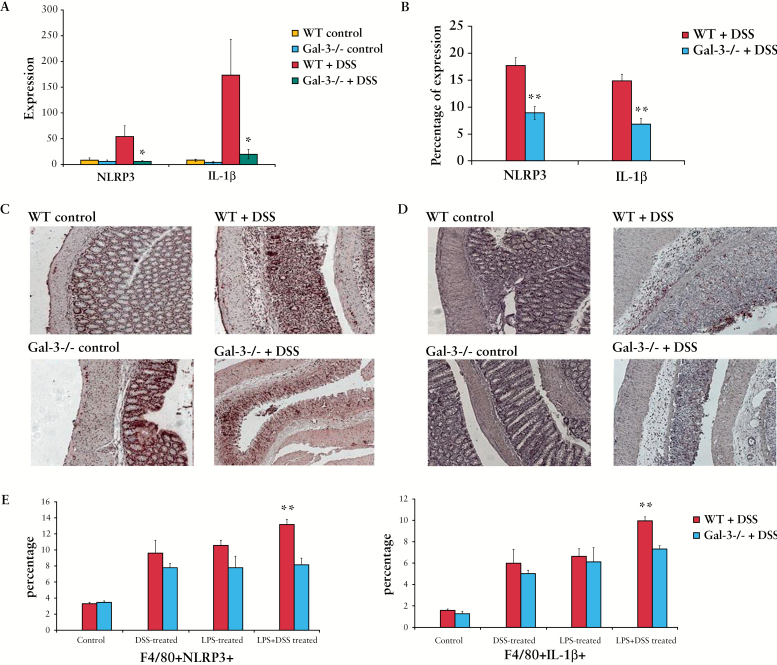

3.10. Gal-3 is important for activation of inflammasome and production of IL-1β in macrophages

Recently, the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages was identified as a critical mechanism of intestinal inflammation in the DSS colitis model.27 Accordingly, we investigated whether genetic deletion of Gal-3 affects activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in colon-infiltrated macrophages.

A real-time RT-PCR analysis of colon tissue from Gal-3-/- and WT DSS-treated mice revealed significantly reduced expression of mRNA encoding NLRP3 and IL-1β in DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice [Figure 9A]. Both NLRP3 and IL-1β were significantly less expressed in colon tissue samples of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice when compared with DSS-treated WT animals [Figure 9B-D C], as determined by immunohistochemistry.

Figure 9.

Galectin-3 [Gal-3] is important for activation of inflammasome and production of interleukin-1 beta [IL-1β] in macrophages. Expression of NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 [NLRP3] and IL-1β in colons of dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-treated mice was determined by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] [A]. NLRP3 and IL-1β were significantly less expressed in colon tissue samples of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice when compared with DSS-treated wild type [WT] animals [B-D], as determined by immunohistochemistry. Peritoneal macrophages isolated from healthy WT and Gal-3-/- mice were treated with increasing concentrations of DSS in the absence or presence of lipopolysaccharide [LPS] priming. The total number of F4/80+NLRP3+ and F4/80+IL-1β+ macrophages was determined by flow cytometry [E]. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] [n = 10 per group]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Flow cytometry analysis of LPS- and DSS-activated peritoneal macrophages showed decreased expression of NLRP3 and IL-1β in Gal-3-/- cells [Figure 9E].

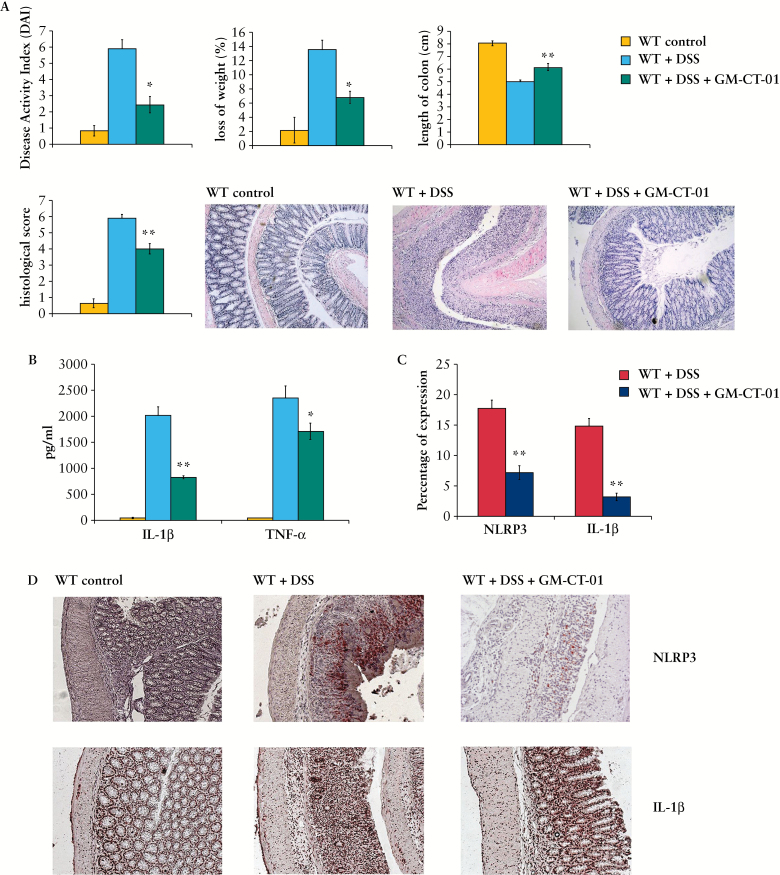

3.11. Pharmacological inhibition of Gal-3 markedly attenuated DSS-induced colitis by reducing activation of inflammasome and production of IL-1β

In line with results obtained from Gal-3-/- mice, GM-CT-01 treatment attenuated DSS-induced colitis, ameliorated diarrhoea and rectal bleeding, and reduced the loss of body weight [Figure 10A]. These findings were confirmed by histological analysis. In DSS-treated mice that received inhibitor, the colonic mucosa showed slight pathological changes including a reduced extent of colon damage and reduced infiltration of inflammatory cells. The structure of the crypt epithelial cells remained intact, and the histopathological injury scores were significantly decreased [p < 0.001] when compared with DSS-treated animals.

Figure 10.

Pharmacological inhibition of Galectin-3 [Gal-3] markedly attenuated dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-induced colitis. Daily weight measurements were obtained for each group of mice. Assessment of daily disease activity measurements, encompassing weight, stool consistency, and presence of blood, was performed for each group of mice [A]. Colon length measurements for each mouse was taken following harvest at Day 7 post DSS and are displayed. Representative histological images are shown. Interleukin-1 beta [IL-1β] and tumour necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α] were determined in the supernatant by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] [B]. Percentage of expression of NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 [NLRP3] and IL-1β in colon tissue [C]. Expression of NLRP3 and IL-1β in colon tissue of healthy wild type [WT] DSS-treated and WT DSS+GM-CT-01-treated mice are demonstrated [D]. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] [n = 10 per group]. * p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Similar to Gal-3-/- mice, activation of inflammasome and production of IL-1β were attenuated in DSS+GM-CT-01 treated mice. The expression of NLPR3 and IL-1 β in colons as well as serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [IL-1β and TNF-α] [Figure 10B-D] were significantly lower in DSS-treated mice after GM-CT-01 treatment, indicating the important role of Gal-3 for inflammasome activation in DSS-induced colitis.

Discussion

The acute DSS-induced colitis as a model is very popular in inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] research due to its rapidity, simplicity, reproducibility, and controllability and is usually used to elucidate molecular and cellular pathways involved in pathogenesis of acute colitis in humans. DSS has a toxic effect on epithelial cells, enabling invasion of intestinal bacteria into subepithelial tissue. During the induction phase of acute colitis, CD14/TLR4:LPS-dependent interaction between macrophages and bacteria that have passed through injured colonic epithelium, results in activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and production of pro-inflammatory IL-1β in macrophages, leading to the development of inflammation in colon tissue.12,27,35,36

However, it should be noted that acute DSS colitis has some limitations.11 Unlike in human disease, T and B cells are not required for development of acute DSS-induced colonic inflammation, and this model is useful only when studying the contribution of the innate immune system to the development of intestinal inflammation.37

Since Gal-3 is involved in migration and function of macrophages, DCs, and neutrophils in inflamed tissues14,15, we used acute DSS colitis to establish the precise role of Gal-3 in cellular and molecular processes that lead to the acute phase of colon inflammation.

Here we provide the first evidence that Gal-3 plays an important pro-inflammatory role in the induction phase of acute colitis by promoting activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β in macrophages. Our findings indicate that genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of Gal-3 significantly reduces activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and production of inflammatory IL-1β in macrophages, resulting in attenuated inflammation and colitis [Figures 9, 10]. We showed that adoptive transfer of peritoneal macrophages isolated from WT healthy animals significantly elevated serum level of IL-1β, and enhanced severity of DSS-colitis in Gal-3-/- mice, suggesting that Gal-3-/- macrophages have reduced capacity for IL-1β production and colon damage [Figure 7]. In vivo depletion of macrophages completely diminished the differences in DSS-colitis between WT and Gal-3-/- mice, further indicating the importance of Gal-3 for macrophage activation in acute colitis [Figure 8].

We also found that LPS- and DSS-activated Gal-3-/- peritoneal macrophages showed decreased expression of NLRP3 and IL-1β compared with WT cells in vitro [Figure 9E] and in vivo [Figure 9A D]. In addition, pharmacological inhibition of Gal-3 markedly attenuated DSS-induced colitis by reducing activation of inflammasome and production of IL-1β [Figure 10], further indicating the importance of Gal-3 for activation of inflammasome in the induction phase of acute colitis. It is well known that Gal-3 plays an important role in macrophage polarisation and function.1 Gal-3 is secreted by activated macrophages at inflammation sites and plays an important role in inflammatory diseases caused by bacteria and their products, such as LPS.38 Monomeric Gal-3 interacts with LPS glycans from LPS aggregates via its C-terminal domain. LPS:Gal-3 interactions induce Gal-3 oligomerisation which promotes the dissolution of LPS aggregates, stabilizes LPS monomers, and enhances the LPS interaction with CD14 leading to increased activation of phagocytes.38 Accordingly, we assume that, during the induction phase of acute colitis, LPS released from intestinal bacteria induce Gal-3 oligomerisation and CD14 clustering on the macrophages, resulting in enhanced CD14/TLR4:LPS-dependent activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β in macrophages [see Supplementary Figure 4, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. These results are in line with our previous findings.3,39 In an animal model of liver steatosis, we noticed attenuated inflammation, reduced number of macrophages, and decreased expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β in the livers of Gal-3 deficient mice.39 In an animal model of type 1 diabetes, we noticed that macrophages of Gal-3-/- mice produce lower amounts of inflammatory cytokines and are less effective in intracellular and extracellular killing compared with WT mice.3

In addition to reduced activation of inflammasome, Gal-3 deletion favoured an alternative activation of macrophages in vitro and in vivo [Figure 6A]. These results are in line with our previous findings obtained in an animal model of acute hepatitis,1 where we found significantly increased numbers of IL-10 producing alternatively activated, M2-polarised macrophages in the livers of Gal-3 deficient mice and in mice pre-treated with selective inhibitor of Gal-3.

By producing inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, DSS-activated macrophages induce migration of neutrophils, DCs, NK, and NKT cells, mast cells, and eosinophils in the colon, leading to progression of acute colitis.12

Targeted disruption of Gal-3 resulted in significantly lower numbers of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12 producing macrophages [Figure 6A], which correlated with significantly reduced numbers of colon-infiltrating inflammatory DCs and neutrophils, whereas the frequency and absolute number of eosinophils, NK, and mast cells were not affected by Gal-3 deletion [Figure 5B].

Gal-3 is important for the migration, adhesion, and maturation of mouse DCs.15 Accordingly, there were significantly lower numbers of inflammatory DCs in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice [Figure 4C]. In pathogenesis of both human and DSS-induced colitis, neutrophils play an important role in phagocytosis of intestinal bacteria passing through the injured colonic epithelium.40 Activated neutrophils are a major source of inflammatory cytokines [TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6] that induce intestinal injury and inflammation.41 Gal-3 serves as a chemo-attractant for neutrophils and plays an important role in phagocytosis.6 Gal-3 increases phagocytic activity of neutrophils and enhances the LPS-mediated activation of neutrophils. In line with these observations, we noticed significantly lower numbers of TNF-α and IL-1β producing neutrophils in colons of DSS-treated Gal-3-/- mice, that correlated with attenuated colitis noticed in these animals [Figure 4D]. However, neither adoptive transfer of WT DCs nor WT neutrophils, isolated from healthy animals, significantly altered the differences in DSS-colitis between WT and Gal-3 deficient mice, suggesting that the reduced number of these cells in colons of DSS-treated Gal3-/- mice was only a consequence of attenuated inflammation caused by reduced activation of Gal-3-/- macrophages in the induction phase of colitis.

It is well known that activation of NKT cells by α-GalCer provides protection against colitis in mice, particularly in an IL-10 dependent manner.34 Here we found significantly higher numbers of protective IL-10 producing NKT cells in colons of DSS-treated Gal3-/- mice. Although administration of α-GalCer managed to significantly reduce colitis and increased total cell numbers of IL-10 producing NKT cells in colons of DSS-treated mice, injection of α-GalCer did not significantly change the difference in disease progression between DSS-treated WT and Gal-3-/- animals, suggesting that genetic deletion of Gal-3 did not directly affect function of NKT cells [see Supplementary Figure 3].

The results obtained in DSS-induced colitis correlate with data obtained from patients with UC. Gal-3 was significantly higher in the colons and sera of patients suffering from UC compared with non-UC controls, and there was a strong correlation between expression of Gal-3, IL-1β, and macrophage lineage marker CD68 [Figure 1] in colons of UC patients. In addition, in vitro LPS-stimulated PBMCs obtained from UC patients produce significantly more Gal-3 then healthy controls [Figure 1C], and the percentage of PBMNCs that express CD14 and Gal-3 was significantly higher in UC patients, indicating the importance of Gal-3 for LPS-dependent activation of macrophages [Figure 1C].

In conclusion, we propose that Gal-3 plays an important pro-inflammatory role in the induction phase of colitis by promoting the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β in macrophages. Gal-3 may serve as a potential target for the development of novel therapeutics for patients with UC.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]: ‘The role of galectin 3 in acute colitis’, and by the Serbian Ministry of Science and Education [projects no.175069 and 175103].

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

BSM, MLL, and VV designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. AN, MG, and SB performed experiments and analysed data. LV, MK, and VT performed PCR analysis. GB provided α-GalCer. SM and MM performed imunohistochemical staining. NA supervised and coordinated the project. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at ECCO-JCC online.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jasmin Nurkovic for excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1. Volarevic V, Milovanovic M, Ljujic B, et al. Galectin-3 Deficiency Prevents Concanavalin A- Induced Hepatitis in Mice. Hepatology 2012;55:1954–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jiang H-R, Al Rasebi Z, Mensah-Brown E, et al. Galectin-3 Deficiency Reduces the Severity of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2009;182;1167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mensah-Brown EP, Al Rabesi Z, Shahin A, et al. Targeted disruption of the galectin-3 gene results in decreased susceptibility to multiple low dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes in mice. Clin Immunol 2009;130;83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Radosavljevic G, Jovanovic I, Majstorovic I, et al. Deletion of galectin-3 in the host attenuates metastasis of murine melanoma by modulating tumor adhesion and NK cell activity. Clin Exp Metastasis 2011;28:451–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Radosavljevic G, Volarevic V, Jovanovic I, et al. The roles of Galectin-3 in autoimmunity and tumor progression. Immunol Res 2012;52:100–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Volarevic V, Lukic ML. Autoimmune disorders in galectin-3 deficient mice. In: Klyosov A, Traber P, editors. Galectins and Disease Implications in Targeted Therapeutics. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society;2012:359–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pejnovic N, Pantic J, Jovanovic I, et al. Galectin-3 Deficiency Accelerates High-Fat Diet Induced Obesity and Amplifies Inflammation in Adipose Tissue and Pancreatic Islets. Diabetes 2013;62:1932–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frol’ová L, Smetana K, Jr, Borovská D, et al. Detection of galectin-3 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: new serum marker of active forms of IBD? Inflamm Res 2009;58:503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Müller S, Schaffer T, Flogerzi B, et al. Galectin-3 modulates T cell activity and is reduced in the inflamed intestinal epithelium in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:588–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brazowski E, Dotan I, Tulchinsky H, et al. Galectin-3 expression in pouchitis in patients with ulcerative colitis who underwent ileal pouch-anal anastomosis [IPAA]. Pathol Res Pract 2009;205:551–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perše M, Cerar A. Dextran sodium sulphate colitis mouse model: traps and tricks. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012;2012:718617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berndt BE, Zhang M, Chen GH, et al. The role of dendritic cells in the development of acute dextran sulfate sodium colitis. J Immunol 2007;179:6255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dieleman LA, Ridwan BU, Tennyson GS, et al. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis occurs in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Gastroenterology 1994;107:1643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu FT, Hsu DK. The role of galectin-3 in promotion of the inflammatory response. Drug News Perspect 2007;20:455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsu DK, Chernyavsky AI, Chen HY, et al. Endogenous galectin-3 is localized in membrane lipid rafts and regulates migration of dendritic cells. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:573–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathieu A, Nagy N, Decaestecker C, et al. Expression of galectins-1, -3 and -4 varies with strain and type of experimental colitis in mice. Int J Exp Pathol 2008;89:438–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Volarevic V, Markovic BS, Bojic S, et al. Gal-3 regulates the capacity of dendritic cells to promote NKT-cell-induced liver injury. Eur J Immunol 2014;45:531–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsu DK, Yang RY, Pan Z, et al. Targeted disruption of the galectin-3 gene results in attenuated peritoneal inflammatory responses. Am J Pathol 2000;156:1073–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okayasu I, Hatakeyama S, Yamada M, et al. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 1990;98:694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Traber PG, Chou H, Zomer E, et al. Regression of fibrosis and reversal of cirrhosis in rats by galectin inhibitors in thioacetamide-induced liver disease. PLoS One 2013;8:e75361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murthy S, Cooper H, Shim H, et al. Treatment of dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine colitis by intracolonic cyclosporine. Dig Dis Sci 1993;38:1722–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whittem CG, Williams AD, Williams CS. Murine Colitis Modeling using Dextran Sulfate Sodium. J Vis Exp 2010;35:1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Obermeier F, Kojouharoff G, Hans W, et al. Interferon-gamma [IFN-gamma]- and tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-induced nitric oxide as toxic effector molecule in chronic dextran sulphate sodium [DSS]-induced colitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol 1999;116:238–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 2002;3:research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Viennois E, Chen F, Laroui H, et al. Dextran sodium sulfate inhibits the activities of both polymerase and reverse transcriptase: lithium chloride purification, a rapid and efficient technique to purify RNA. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scheiffele F, Fuss IJ. Induction of TNBS Colitis in Mice. Curr Protoc Immunol 2002;15:15–19.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bauer C, Duewell P, Mayer C, et al. Colitis induced in mice with dextran sulfate sodium [DSS] is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Gut 2010;59:1192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Medina-Contreras O, Geem D, Laur O, et al. CX3CR1 regulates intestinal macrophage homeostasis, bacterial translocation, and colitogenic Th17 responses in mice. J Clin Invest 2011;121:4787–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weisser SB, van Rooijen N, Sly LM. Depletion and reconstitution of macrophages in mice. J Vis Exp 2012;66:4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murphy CT, Moloney G, Hall LJ, et al. Use of bioluminescence imaging to track neutrophil migration and its inhibition in experimental colitis. Clin Exp Immunol 2010;162:188–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zindl CL, Lai JF, Lee YK, et al. IL-22-producing neutrophils contribute to antimicrobial defense and restitution of colonic epithelial integrity during colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:12768–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abe K, Nguyen KP, Fine SD, et al. Conventional dendritic cells regulate the outcome of colonic inflammation independently of T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:17022–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim HS, Chung DH. IL-9-producing invariant NKT cells protect against DSS-induced colitis in an IL-4-dependent manner. Mucosal Immunol 2013;6:347–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saubermann LJ, Beck P, De Jong YP, et al. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide in the presence of CD1d provides protection against colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2000;119:119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qiao Y, Wang P, Qi J, et al. TLR-induced NF-κB activation regulates NLRP3 expression in murine macrophages. FEBS Lett 2012;586:1022–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guarda G, Zenger M, Yazdi AS, et al. Differential expression of NLRP3 among hematopoietic cells. J Immunol 2011;186:2529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chassaing B, Aitken JD, Malleshappa M, Vijay-Kumar M. Dextran sulfate sodium [DSS]-induced colitis in mice. Curr Protoc Immunol 2014;4;104:Unit 15.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fermino ML, Polli CD, Toledo KA, et al. LPS-induced galectin-3 oligomerization results in enhancement of neutrophil activation. PLoS One 2011;6:e26004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jeftic I, Jovicic N, Pantic J, et al. Galectin-3 Ablation Enhances Liver Steatosis, but Attenuates Inflammation and IL-33 Dependent Fibrosis in Obesogenic Mouse Model of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Mol Med 2015; 21:453–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. D’Odorico A, D’Inca R, Mestriner C, et al. Influence of disease site and activity on peripheral neutrophil function in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2000;45:1594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Steinbeck MJ, Roth JA, Kaeberle ML. Activation of bovine neutrophils by recombinant interferon-gamma. Cell Immunol 1986;98:137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]