Abstract

Objective

To analyze and compare dental knowledge between two generations of pregnant women attending the same antenatal clinic in Al-Jubail, Saudi Arabia.

Methods

A cross sectional self administered questionnaire was conducted among 252 pregnant women in three different antenatal clinics. Data were analyzed using SPSS (v. 21), p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Most surveyed women were knowledgeable about dental health issues, although a large percentage did not visit dental clinics regularly during pregnancy. Results showed a decline in dental knowledge, compared with data collected 22 years ago. Pregnant women participating in the current survey had more dental problems and underwent more dental procedures than did those participating in the previous survey.

Conclusions

Results of this study show a decline in dental knowledge and oral health in pregnant women of the current generation, compared with those of the previous generation. Antenatal clinics should educate pregnant women more about the relationship between good oral and fetal health.

Keywords: Dental knowledge, Antenatal clinic, Generational comparison

1. Introduction

Pregnancy is one of the most important stages in a woman’s life. In this stage, a woman feels that she has become responsible not only for her health, but also for the health and well-being of the fetus growing in her. Pregnancy makes a woman more aware of all health issues and how they might relate to or be predisposing factors for her child’s future health. Pregnant women thus become more receptive to all health information.

Antenatal clinics educate pregnant women about relevant health issues, but clinicians unfortunately neglect the importance of oral health. Furthermore, several studies have documented low utilization of antenatal dental services (Gaffield et al., 2001, Mangskau and Arrindell, 1996). Some statistics show that the majority of pregnant women do not visit a dentist during pregnancy (Lydon-Rochelle et al., 2004, Marchi et al., 2010). In addition, the underlying belief among pregnant women that pregnancy and fetal health and nutritional requirements lead to tooth loss and many other oral health issues has been documented. Patients’ lack of knowledge regarding oral health care during pregnancy may be a contributing factor to the low dental visitation rate (Timothe et al., 2005). Moreover, on some occasions, dental health providers choose to postpone major dental procedures until after delivery to avoid health risks to the mother and child; this behavior intensifies the belief that dental health care might pose risks to the fetus (Gaffield et al., 2001, Lydon-Rochelle et al., 2004). On the other hand, observational studies have shown significant correlations between poor oral health, particularly periodontal disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth and low birth weight (Jeffcoat et al., 2011, Lopez et al., 2005). Hormonal changes during pregnancy have also been shown to induce edema, hyperemia, bleeding in dental tissues, and increased risk of bacterial infection (Leine, 2002, Tanni et al., 2003). These results should be utilized more in antenatal clinics to educate pregnant women and promote oral health care during pregnancy.

In this study, we investigated differences in perceptions of dental health during pregnancy between pregnant women from two generations in the same location. We repeated a survey conducted in 1993 (Assery and Al-Saif, 1993), with some modifications to enable additional data collection. The survey consisted of questions about pregnant women’s oral health care knowledge, attitudes, and habits. We conducted the survey in the same antenatal clinic in which the 1993 survey was conducted to reduce differences in variables that may affect the results.

2. Methods

A self administered closed ended questionnaire was used. The questionnaire was divided into four sections, dental health knowledge, personal dental history and habits, current dental status and antenatal care (Appendix A). A total of 300 pregnant mothers were recruited and 252 responsed (84%) response rate. Questionnaire forms were distributed and collected with the help of a female social worker on the same day from the pregnant mothers while waiting in the antenatal clinic. The survey was conducted for 3 months from March 2014 to May 2014.

Descriptive statistics was performed and frequency tables were generated. All categorical variables were analyzed using cross tabulation and chi square test and continuous variables were compared using t-test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (v. 21; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

A total of 252 expectant mothers from the Al-Jubail antenatal clinic population participated in the survey. Eighty-three (32.9%) women were aged <20 years, 67 (26.5%) were aged 21–30 years, 65 (25.8%) were aged 31–40 years, and 37 (14.7%) women were aged ⩾40 years. The median age range of the respondents was 21–30 years. Sixty-four (25.4%) women were in their first gestation, 71 (28.2%) were in their second gestation, 42 (16.7%) were in their third gestation, and 75 (29.8%) women were in their fourth or more gestation.

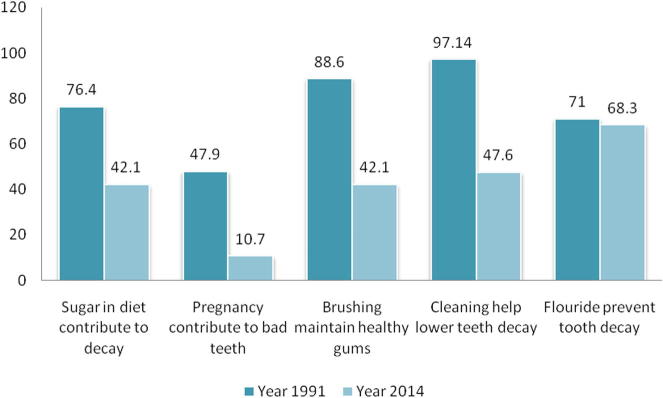

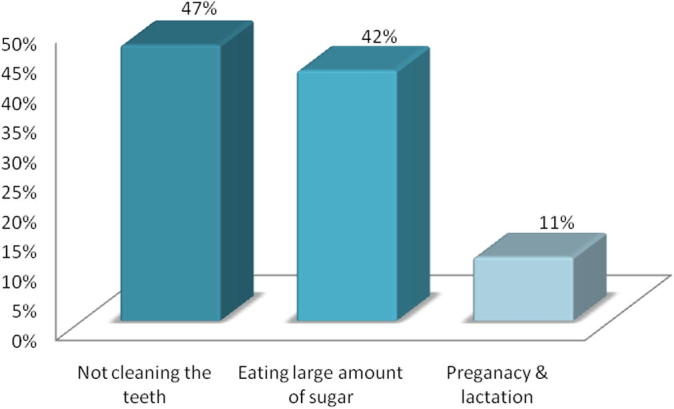

Respondents believed that the following factors caused tooth decay: not cleaning the teeth (n = 118, 47%), eating a large amount of sugar (n = 106, 42%) and pregnancy and lactation (n = 28, 11%). The latter percentage was significantly smaller than the percentages of the other two responses (p < 0.05; Fig. 1). Almost half (n = 125, 49.6%) of respondents perceived that pregnancy leads to tooth decay; the remaining 127 (50.4%) or respondents believed that it did not. Out of 252 respondents, 117 (46%) respondents believed that negligence in tooth cleaning causes tooth decay in pregnant women, 93 (37%) believed that the fetus draws calcium from the mother’s teeth, and 42 (17%) respondents believed that malnutrition affects the oral health of pregnant women (p < 0.05; Fig. 2). The pregnant women indicated the following perceived causes of gum inflammation during pregnancy: negligence in cleaning the teeth and gums (n = 113, 44.8%), pregnancy (n = 90, 35.7%), and malnutrition (n = 49, 19.4%; p < 0.05; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Dental knowledge among pregnant women regarding the causes of tooth decay.

Figure 2.

Perception of pregnant women on the effect of pregnancy on their oral health and teeth.

Table 1.

Perception of the pregnant women on the effect of cleaning the teeth on oral health.

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Lower teeth decay | 120 | 47.6 |

| Keep the gum healthy | 106 | 42.1 |

| Has no effect on caries and gums | 26 | 10.3 |

| Total | 252 | 100.0 |

Participants believed that tooth cleaning had the following effects on oral health: reducing tooth decay (n = 120, 47.6%), maintaining healthy gums (n = 106, 42.1%), and no effect on caries prevention or gingival health (n = 26, 10.3%; Table 1). The latter percentage was significantly smaller than the percentages of the other two responses (p < 0.05). More than two-thirds (n = 172, 68.3%) of respondents knew what fluoride was and agreed that fluoride intake is of great importance in preventing tooth decay (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perception of pregnant women as the cause of gum inflammation during pregnancy.

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy can cause inflammatory gum | 90 | 35.7 |

| Negligence in cleaning teeth and gum | 113 | 44.8 |

| Malnutrition of pregnant mothers | 49 | 19.4 |

| Total | 252 | 100.0 |

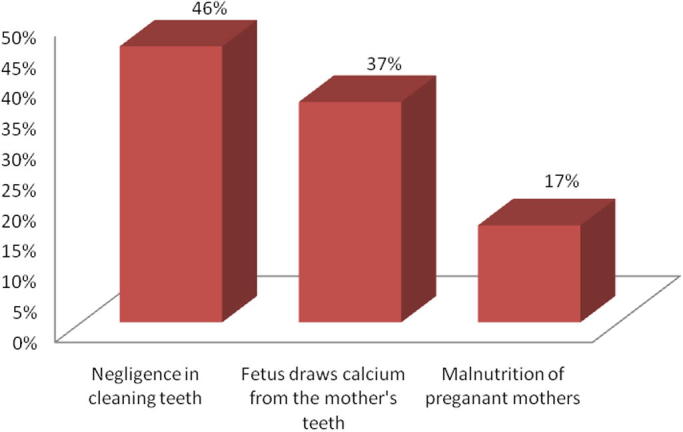

Out of 247 respondents (n = 115, 45.6%) responded that dental treatment during pregnancy is best performed in the second trimester, followed by the first trimester (n = 98, 38.9%) and the third trimester (n = 34, 13.5%). Ninety five (37.7%) respondents reported that they obtained dental knowledge from dentists and dental hygienists, followed by television and printed media (n = 84, 33.3%) and online internet sources (n = 39, 15.5%). Comparison of 2014 with 1991 survey data showed a significant decrease in dental knowledge (means lower scores) (p < 0.05). Knowledge that sugar in the diet may contribute to decay and that toothbrushing maintains healthy gums and reduces tooth decay declined by 50%. No significant change was observed in the knowledge that fluoride prevents tooth decay (Fig. 3). A significant decrease (by 80%) was observed in the perception that pregnancy may contribute to poor dental health (p < 0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison in the dental knowledge among pregnant women between year 1991 and year 2014.

3.1. Personal dental health practices

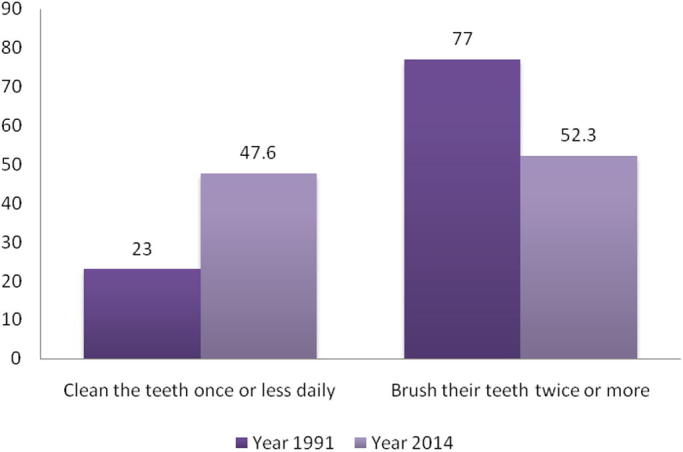

Eighty-three (32.9%) respondents reported that they brushed their teeth once a day, 84 (33.3%) reported that they brushed their teeth twice, 48 (19%) reported that they brushed their teeth three times a day, and 37 (14.7%) reported that they never brushed their teeth (Table 3). Compared with 1991 data, these results show a nearly 50% increase in the percentage of pregnant women who brushed their teeth once or less per day (from 23% to 47.6%; proportional t-test, p < 0.05), and a significant decrease in the percentage of women who brushed their teeth more than once a day (from 77% to 52.3%; proportional t-test, p < 0.05; Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Oral health practice and tooth brushing among pregnant women in the clinic.

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 37 | 14.7 |

| Once | 83 | 32.9 |

| Twice | 84 | 33.3 |

| Thrice | 48 | 19.0 |

| Total | 252 | 100.0 |

Figure 4.

Comparison of the brushing habits of pregnant women between year 1991 and year 2014.

Out of 249 respondents, 110 (43.7%) respondents had visited the dentist more than twice in their lifetimes, 100 (39.7%) reported two visitations and 39 (15.5%) had never visited a dentist Respondents indicated that the main reasons for not visiting the dentist regularly were fear (n = 172, 68.3%), difficulty making appointments (n = 47, 18.7%), and financial reasons (n = 19, 7.5%). Compared with 1991 data, these results show significant increases in the percentages of pregnant women who had visited the dentist more than once (from 67% to 83%) in their lifetimes (proportional t-test, both p < 0.05).

3.2. Current dental status

Ninety (35.7%) respondents were currently under dental treatment and 157 (62.3%) were not. Similar percentages of expectant mothers had carious teeth (29.8%) and healthy teeth and gums (29.4%); 24.6% had inflamed and bleeding gums and 13.5% reported severe pain in the teeth. Compared with the 1991 data, these results show a significant increase (from 19% to 35.7%) in the percentage of pregnant women undergoing dental treatment. No significant change was observed in the percentages of women with tooth (39% vs. 29%) and gum (22% vs. 24.6%) problems.

3.3. Antenatal clinic care

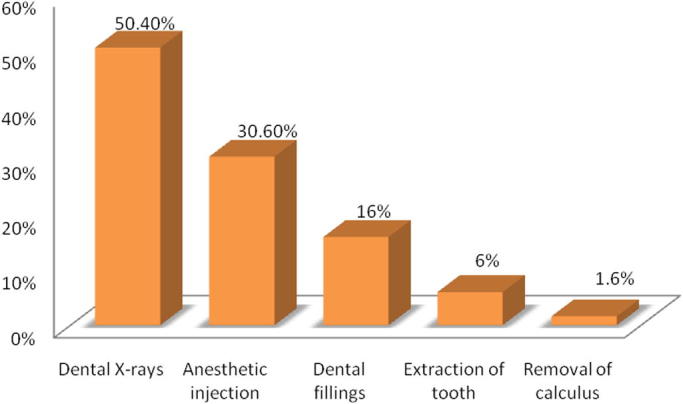

Pregnant women’s perceptions of dental health hazards to the fetus were reflected in monthly dental clinic visitation during pregnancy among 48.4% (n = 122) of respondents and weekly scheduled visits during the last month of pregnancy among 34.9% (n = 88) of respondents. The majority (n = 148, 58.7%) of respondents in 2014 were not advised by their doctors to visit the dental clinic, a decrease from 83% in 1991. About half (n = 128, 50.8%) of the 2014 respondents believed that dental treatment during pregnancy adversely affected the fetus. The treatment component perceived by the largest proportion of women to affect fetal health was dental X-rays (n = 127, 50.4%), followed by anesthetic injection (n = 77, 30.6%); dental fillings, tooth extraction, and calculus removal were the least frequently reported treatment components perceived to have adverse effects on fetal health (chi-squared test, p < 0.05; Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Perception of pregnant women on the dental health hazards to the fetus.

Results of this survey showed that most pregnant women were knowledgeable about dental health. Compared with the previous survey conducted in the same clinic (Assery and Al-Saif, 1993), more pregnant women had been to the antenatal clinic more than once (86% vs. 98.8%). However, more than half of pregnant women surveyed in 2014 were not receiving dental care; this finding is consistent with results of the studies conducted in Australia and the United States (Lydon-Rochelle et al., 2004, Thomas et al., 2008). A study conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Al-Swuailem et al., 2014), showed that lack of perceived need for dental treatment and concerns regarding the safety of dental treatment during pregnancy were the main reasons that women did not visit the dentist during pregnancy.

The majority of women surveyed reported signs of periodontal disease (bleeding gums and pain) during pregnancy, in agreement with the results reported by Tanni and colleagues (2003). This study showed a significant decline in dental knowledge in the current generation of pregnant women visiting an antenatal clinic in comparison with the population surveyed in 1991 (Assery and Al-Saif, 1993). Furthermore, reported barriers to the seeking of dental care during pregnancy included financial barriers, such as lack of dental insurance and low income (Al-Swuailem et al., 2014).

3.4. Current dental status

A larger percentage of expectant mothers in 2014 were undergoing dental treatment compared with the previous generation. Al-Kanhal and Bani (1995) reported that pregnant Saudi women had dietary cravings for milk, salty and sour foods, sweets, and dates, and were at greater risk of dental caries and erosion compared with non pregnant women.

3.5. Antenatal clinic care

Pregnant women surveyed in 2014 reported monthly antenatal clinic visitation, and weekly visitation in the last month of pregnancy. In contrast, women in the previous generation reported irregular visitation patterns or only a single visit to the antenatal clinic during pregnancy. Moreover, the majority of participants in the previous survey were advised by their doctors to visit the dentist, in contrast to the results obtained for the present generation. However, pregnant women in the current generation were found to be more concerned about the adverse effects of dental procedures on the fetus; in contrast, women in the previous generation were willing to attend dental treatment as a part of antenatal service, if a dentist were provided.

Continuous implementation of dental health awareness initiatives among pregnant women in Saudi Arabia and the identification of barriers to treatment seeking during pregnancy are needed. Dental professionals need to educate pregnant women on the importance of oral health care to themselves and their babies during and after pregnancy. Obstetricians could provide further assurance about the safety of dental care during pregnancy and encourage pregnant women to regularly visit to dental care centers when needed.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Ashwin Shitty and Dr. Tahani Alrahbeni for their help and also Dr. Muna Almubayed for her cooperation in data collection.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Al-Kanhal M.A., Bani I.A. Food habits during pregnancy among Saudi women. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1995;65(3):206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Swuailem A.S., Al-Jamal F.S., Helmi A.F. Treatment perception and utilization of dental services during pregnancy among sampled women in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Dent. Res. 2014;5(2):123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Assery M.K., Al-Saif K.M. A survey of dental knowledge in Al-Jubail antenatal clinic population. Saudi Dent. J. 1993;5(1):13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffield M.L., Gilbert B.J., Malvitz D.M., Romaguera R. Oral health during pregnancy: an analysis of information collected by the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2001;132:1009–1016. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoat M., Parry S., Sammel M., Clothier B., Catlin A., Macones G. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: successful periodontal therapy reduces the risk of preterm birth. BJOG. 2011;118(2):250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leine M.A. Effect of pregnancy and dental health. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2002;60:257–264. doi: 10.1080/00016350260248210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez N.J., Da Silva I., Ipinza J., Gutierrez J. Periodontal therapy reduces the rate of preterm low birth weight in women with pregnancy-associated gingivit. J. Periodontol. 2005;76(11 (Suppl.)):2144–2153. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon-Rochelle M.T., Krakowiak P., HujoeL P.P., Peters R.M. Dental care use and self-reported dental problems in relation to pregnancy. Am. J. Public Health. 2004;94(5):765–771. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangskau K.A., Arrindell B. Pregnancy and oral health: utilization of the oral health care system by pregnant women in North Dakota. Northwest Dent. 1996;75:23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi K.S., Fisher-Owen S.A., Weintraub J.A., Yu Z., Braveman P.A. Most pregnant women in California do not receive dental care: findings from a population-based study. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(6):831–842. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanni D.Q., Habashneh R., Hammad M.M., Batieha A. The periodontal status of pregnant women and its relationship with socio-demographic and clinical variables. J. Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:440–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas N.J., Middleton P.F., Crowther C.A. Oral and dental health care practices in pregnant women in Australia: a postnatal survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timothe P., Eke P.I., Presson S.M., Malvitz D.M. Dental care use among pregnant women in the United States reported in 1999 and 2002. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]