Abstract

Introduction

Pessaries are commonly used to treat pelvic floor disorders, but little is known about the sexual function of pessary users.

Aim

We aimed to describe sexual function among pessary users and pessary management with regard to sexual activity.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of a randomized trial of new pessary users, where study patients completed validated questionnaires on sexual function and body image at pessary fitting and 3 months later.

Main outcome measures

Women completed the Pelvic Organ Prolapse - Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire, IUGA Revised (PISQ-IR), a validated measure that evaluates the impact of pelvic floor disorders on sexual function, a modified female body image scale (mBIS), and questions regarding pessary management surrounding sexual activity.

Results

Of 127 women, 54% (68/127) were sexually active at baseline and 42% (64/114) were sexually active at 3 months. Sexual function scores were not different between baseline and 3 months on all domains except for a drop of 0.15 points (p=0.04) for sexually active women and a drop of 0.34 points for non-sexually active women (p=0.02) in the score related to the sexual partner. Total mBIS score did not change (p=0.07), but scores improved by 0.2 points (p=0.03) in the question related to self-consciousness. Pessary satisfaction was associated with improved sexual function scores in multiple domains and improved mBIS scores. The majority (45/64, 70%) of sexually active women removed their pessary for sex, with over half stating their partner preferred removal for sex (24/45, 53%).

Conclusion

Many women remove their pessary during sex for partner considerations, and increased partner concerns are the only change seen in sexual function in the first 3 months of pessary use. Pessary use may improve self-consciousness and pessary satisfaction is associated with improvements in sexual function and body image.

Keywords: Pessaries, sexual function, sexual activity, body image, partner, remove, hygiene

Introduction

Pelvic floor support disorders are common and debilitating to women, resulting in a significant deterioration in quality of life and overall health. A quarter of women have at least one symptomatic pelvic floor disorder.1 Pessaries, a variety of flexible devices worn in the vagina for pelvic organ support, are used by 75% of specialist physicians who treat these disorders.2 Women who use pessaries enjoy improvement in their pelvic floor symptoms and a better quality of life,3,4 but there are a lack of data to guide women in how to best manage their pessary hygiene to optimize their experience with the pessary, particularly in regard to sexual activity.5

Pessary use to treat pelvic floor disorders positively impacts a woman’s body image and sexual function6,7 and sexual activity is associated with pessary continuation.8 However, women using a pessary may not enjoy the same improvement in sexual function as women receiving other non-surgical treatments for pelvic floor disorders,9 perhaps due to special sexual considerations with pessary use. Very little is known about pessary management during sexual activity, and many women considering pessary use have concerns about sexual activity and function while using an intravaginal device. More knowledge about sexual function in the setting of pessary use may better address the concerns of women and their partners when considering this treatment option.

Aims

The aim of this study was to describe sexual function in a cohort of pessary users entering a randomized trial, and describe sexual practices and pessary management around sexual activity in this group of pessary users. We also sought to describe what other factors influence sexual function and body image in this group of women. We hypothesized that sexual activity rates and sexual function would improve after 3 months of pessary use, particularly in women who were satisfied with their pessary.

Materials and Methods

This is a planned secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (NCT01471457) that investigated the use of a hydroxyquinoline-based vaginal gel, for the prevention bacterial vaginosis (BV) in pessary users.10 Women presenting for a pessary fitting at one of the two tertiary care centers were recruited and randomized according to the parent trial design. Women enrolled at the University of New Mexico (UNM) were included in this secondary analysis of sexual function in pessary users. Patients were fitted with a pessary and instructed on pessary care individual to their medical needs and pessary type was determined by a nurse midwife in a specialty pessary clinic. Vaginal estrogen was prescribed and utilized in women who did not have contraindications to its use and who were hormonally menopausal, not utilizing oral hormones, and/or with significant vaginal atrophy.

Women were excluded if they were younger than 18 years of age, had a known allergic or suspected adverse reaction to hydroxyquinoline-based gel or any of its components, were unable to use a pessary or the gel as indicated, had used a pessary within the last year, had frequent or chronic BV (>2 episodes per year or symptoms >6 months out of the last 12 months), had active vaginal ulcerative disease (active ulcers from atrophy, herpes, or mesh erosion with >2 episodes of ulcers per year or last ulcer <1 month ago), were using long-term antibiotics for indications not listed above, were unable to speak English, were unable to provide informed consent, or were unable to be fitted with a pessary.

Women were seen at pessary fitting and 2 weeks and 3 months after the pessary fitting. At all study visits, women completed questionnaires on their medical history and health, use of hormone therapy (HT) orally and/or vaginally, any vaginal products or medications, and vaginal symptoms (including vaginal discharge, itching, pain, and sores), frequency of wearing the pessary, and frequency of pessary removal (defined as “frequent” if removed the pessary daily or more often). At follow up, women also completed questionnaires on how often they used hydoxyquinoline-based gel (TrimoSan by Milex Pessary©, Trumbell, CT).

At baseline and 3 months, women in the study completed the Pelvic Organ Prolapse - Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire, IUGA Revised (PISQ-IR).11 This questionnaire is validated for both sexually active and non-sexually active women with pelvic floor disorders, and the questions answered by the patient differ based on whether the women designates herself as “sexually active with or without a partner” or “not sexually active at all” at the beginning of the questionnaire. The portion of the questionnaire designed for women who report no sexual activity is meant to evaluate the impact of their pelvic floor dysfunction on the choice to be inactive. For both sexually active and non-sexually active women, higher scores in individual domains (global quality rating, condition specific, condition impact, and partner related domains for non-sexually active women and global quality rating, condition specific, condition impact, desire, arousal/orgasm, and partner related domains for sexually active women) indicate improved better sexual function in the area of that domain. No total score exists for the PISQ-IR, as the relative importance of each domain to overall sexual function in women is not yet known, and the minimally important difference for individual domains are also not yet established.11

Women also completed a modified version of a validated female body image scale (mBIS), a scale of 8 questions modified to be relevant to women with pelvic floor disorders,12,13 in which a lower total score indicates better body image. To further describe women’s behavior with the pessary surrounding sex, sexually active women answered questions regarding pessary management during sexual activity, such as removing the pessary for sex, and the reasons for this behavior, such as personal or partner preference.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome in this planned secondary analysis was the change in PISQ-IR domain scores from the initial visit to 3 months later. The parent study was originally powered for the effect of the hydroxyquinoline-based gel on BV.10 However, based on validation studies of the PISQ-IR, an average score 3.3 ± 0.6 was expected for sexually active patients on a given domain,11 and we estimated in a post-hoc analysis that we would require a total of 43 sexually active patients in the analysis to detect a change of a half standard deviation (0.3 points) from a mean of 3.3 or less in the PISQ-IR score from baseline to 3 months with 90% power (α = 0.05). In the absence of a known minimally important difference (MID), one half a standard deviation of a baseline value has been used as an approximation of the MID.14 As a mean domain score on the PISQ-IR for non-sexually active patients have been found to be 2.9 ± 0.5,11 we would require 43 non-sexually active patients to achieve 90% power (α = 0.05) in order to detect a half standard deviation change (0.25 points) in the PISQ-IR domain scores from baseline to 3 months.

Secondary outcomes in this analysis included the change in body image on the mBIS from baseline to 3 months, the frequency of removal of the pessary for sex and the frequency of various given reasons for this practice, and the effect of various pessary hygiene practices and patient characteristics on sexual function and body image.

Paired t-tests were used to compare sexual function on the PISQ-IR (women compared to themselves within PISQ-IR domains) and mBIS scores between baseline and 3 months. Only women who reported sexual activity or inactivity at both time points were compared to themselves by the paired t-test for PISQ-IR domain scores. In contrast, all women who completed the mBIS at both baseline and 3 months (regardless of sexual activity) had mBIS scores compared by the paired t-test.

The effect of continuous variables on dichotomous outcomes was determined by logistic regression. The effect of dichotomous variables on dichotomous outcomes was determined by logistic regression, with Fisher’s exact test used where the number of data points in a field were too few for logistic regression to be appropriate. We utilized regression analysis to determine the effect of dichotomous variables and continuous variables on the continuous outcomes. General linear models were used to examine the effect of hygienic practices (HT use, frequent pessary removal, hydroxyquinoline gel use) on the relationship between vaginal symptoms and the continuous outcomes. Standardized beta statistics (STB) were generated to standardize and report these relationships between independent variables and continuous outcomes. Statistical significance for all tests was set at p≤0.05.

Results

As reported previously, there were 184 women recruited in the parent study.10 One hundred and twenty-seven of these women, or 69% (127/184), were recruited from the parent study at the UNM study site and were eligible for the sexual function analysis and completed baseline sexual function questionnaires. Women in this analysis had a mean age of 56 ± 16 years, a mean BMI of 29 ± 8 kg/m2, and were mostly Caucasian (55%) or Hispanic (34%). The majority of patients in this study (85/127, 67%) were fitted with a ring pessary, further divided into a ring with support (44/127, 35%), a ring without support (21/127, 17%), a ring without knob in which with or without support was unknown (17/127, 13%), or a ring with knob (3/127, 2%). Other pessary types utilized in this study included the incontinence dish (8/127, 6%), the incontinence ring (15/127, 12%), Shaatz (1/127, 1%), and the short-stem Gellhorn (2/127, 2%). The pessary type utilized was unknown in 10% (13/127) of the participants.

Patient characteristics for this study population and compared between those who reported sexual activity at baseline (68/127, 54%) and those who did not (59/127, 46%) are demonstrated in Table 1. Women who were sexually active at baseline were younger (51 ± 13 vs. 63 ± 17 years, p<0.01) and had lower Charleston comorbidity scores (median 0 (IQ range 0–1) vs. 1 (IQ range 0–2), p=0.01) than women were non-sexually active, but they were otherwise similar in patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in women participating in the sexual function evaluation, compared between women who were and were not sexually active at baseline.

| All Women in Sexual Function Analysis (n=127) (mean ± standard deviation or median (IQ range) or n(%)) |

Sexually Active Women at Baseline (n=68) (mean ± standard deviation or median (IQ range) or n(%)) |

Sexually Non-Active Women at Baseline (n=59) (mean ± standard deviation or median (IQ range) or n(%)) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 56.0 ± 16.2 | 50.5 ± 13.1 | 62.6 ± 17.2 | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.8 ± 7.8 | 28.7 ± 7.8 | 28.9 ± 7.8 | 0.88 |

|

| ||||

| Charleston Comorbitidy Index | 0 (0 – 1) | 0 (0 – 1) | 1 (0 – 2) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Parity | 3 (2 – 4) | 3 (2 – 3) | 3 (2 – 4) | 0.65 |

|

| ||||

| Vaginal Deliveries | 2 (2 – 3) | 3 (2 – 3) | 2 (1 – 4) | 0.94 |

|

| ||||

| Race | 0.09 | |||

| Caucasian | 69 (55) | 39 (58) | 30 (52) | |

| Hispanic | 42 (34) | 24 (36) | 18 (31) | |

| Asian | 3 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | |

| Other | 11 (9) | 2 (3) | 9 (16) | |

|

| ||||

| Education Level | 0.25 | |||

| Less Than High School | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | |

| High School | 35 (29) | 16 (25) | 19 (33) | |

| College or Beyond | 82 (67) | 47 (73) | 35 (60) | |

|

| ||||

| Insurance | 0.10 | |||

| Private | 50 (43) | 31 (52) | 9 (16) | |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 42 (36) | 19 (32) | 23 (41) | |

| No insurance | 12 (10) | 7 (12) | 5 (9) | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking | 0.69 | |||

| Never | 74 (59) | 40 (60) | 34 (59) | |

| Past | 39 (31) | 22 (33) | 17 (29) | |

| Current | 12 (10) | 5 (7) | 7 (12) | |

|

| ||||

| Pessary Indication | 0.98 | |||

| Prolapse | 41 (34) | 22 (34) | 19 (33) | |

| Incontinence | 59 (49) | 31 (48) | 28 (49) | |

| Both prolapse and incontinence | 18 (15) | 9 (14) | 9 (16) | |

|

| ||||

| Prior Pelvic Surgery | 52 (42) | 33 (49) | 19 (33) | 0.07 |

|

| ||||

| HT Use (Any) | 35 (28) | 15 (22) | 20 (34) | 0.17 |

|

| ||||

| HT Use (Vaginal) | 19 (15) | 10 (15) | 9 (15) | 0.99 |

P-values shown are for the comparisons between women who did and did not report sexual activity at baseline

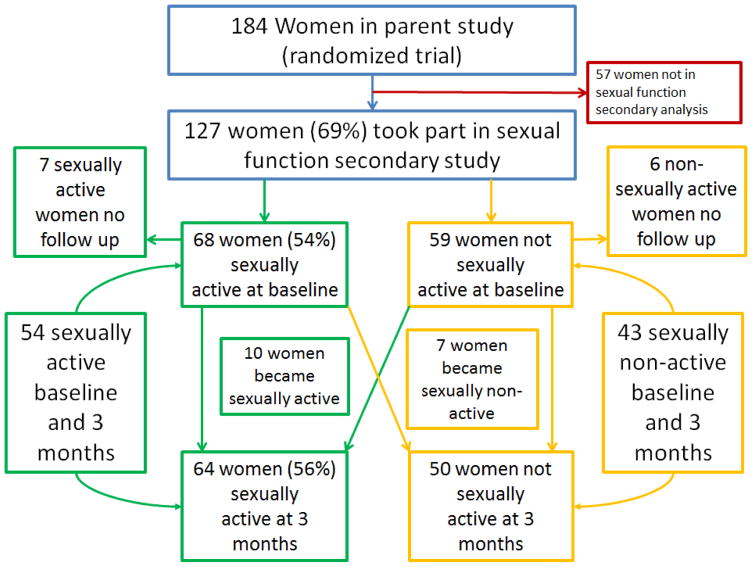

Of the 127 women in this analysis, 114 women (90%) followed up at 3 months and completed sexual function questionnaires. There were 13 women who were lost to follow up, seven (7/13, 54%) from the sexually active group and six (6/13, 46%) from the non-sexually active group. Starting with 68 women who were sexually active at baseline, 7 were lost to follow up, 7 became sexually non-active, and 10 additional women became sexually active, yielding a total of 64 women sexually active at 3 months. Women who were sexually active constituted 56% (64/114) of the population that followed up at 3 months. Starting with 59 women who were not sexually active at baseline, 6 were lost to follow up, 10 became sexually active, and 7 became sexually non-active, yielding a total of 50 women (50/114, 44%) who were sexually active at 3 months. Figure 1 shows the flow of patients through the study and the sexually active and non-sexually active populations of interest.

Figure 1.

Flow sheet of patients

Table 2 demonstrates the mean sexual function domain scores and modified body image scale (mBIS) scores at 3 months after pessary fitting, and the mean changes from baseline to 3 months. Amongst the 54 women consistently sexually active through the study, sexual function scores did not change between baseline and 3 months on any domains of the PISQ, with the notable exception of the score related to the sexual partner, where scores dropped significantly by 0.15 points (p=0.04). For the 43 women consistently not sexually active throughout the study, PISQ-IR scores also only changed in the domain related to the sexual partner, where there was a decrease of 0.34 points (p=0.02). The total mBIS scores amongst the 110 women who completed this at baseline and 3 months showed a 0.8 point increase that was not significant (p=0.07), but scores did significantly improve by 0.2 points (p=0.03) in the question related to self-consciousness.

Table 2.

Mean sexual function domain scores and modified body image scale (mBIS) scores at 3 months and the mean change from baseline, with paired t-test p-value for the comparison between baseline and 3 months.

| Baseliine Score ± Standard Deviation | 3 Month Score ± Standard Deviation | Mean Change from Baseline Score ± Standard Deviation | p-value (paired t-test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PISQ-IR Domains Scores for Sexually Active Women (n=54) | ||||

| Global Quality Rating* | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 0.03 ± 0.47 | 0.68 |

| Condition Specific* | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 0.16 ± 0.70 | 0.13 |

| Condition Impact** | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.18 ± 0.74 | 0.09 |

| Desire* | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | −0.04 ± 0.60 | 0.63 |

| Arousal/Orgasm* | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0.13 ± 0.61 | 0.11 |

| Partner-Related** | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | −0.15 ± 0.55 | 0.045 |

| PISQ-IR Domains Scores for Sexually Non-Active Women (n=45) | ||||

| Global Quality Rating* | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | −0.06 ± 0.89 | 0.67 |

| Condition Specific** | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 0.19 ± 0.84 | 0.18 |

| Condition Impact** | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | −<0.01 | 0.97 |

| Partner-Related** | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | −0.34 ± 0.92 | 0.02 |

| Modified Body Image Scale (mBIS) for both Sexually Active and Sexually Non-Active Women (n=110) | ||||

| Total mBIS Score¶ | 6.0 ± 5.9 | 5.1 ± 5.6 | −0.79 ± 4.45 | 0.07 |

Score range for items 1 – 5, higher scores indicate better sexual function in this domain

Score range for items 1 – 4, higher scores indicate better sexual function in this domain

Score range 0–24, lower scores indicate better body image

Amongst sexually active women at 3 months, 70% (45/64) removed their pessary for sex “usually” or “always”, with the most common reasons cited being that the “partner can feel during sex” (14/45, 31%) and that the “pessary is uncomfortable during sex” (9/45, 20%). Roughly half of the women removing the pessary for sex believed their partner wanted them to remove it for intercourse (24/45, 53%), with nearly all of the women reporting that they were told this by their partner (22/24, 92%) and that most of these partners (20/22, 91%) communicated to the patient a specific reason for this request. The most common reason women stated had been given by partners for preferring pessary removal for sex were the partner being able to “feel the pessary during sex” (7/22, 32%) and “concern [by the partner] that the pessary would hurt [the woman]” during intercourse (8/22, 36%), with fewer women reporting that their partners gave the reason of “cannot have sex in certain positions with pessary in” (1/22, 5%) or “other reason given” (4/22, 18%). No patients gave the reason of “vaginal discharge” or “vaginal odor” as a reason for removing the pessary during sex, and no patient reported that their partners had given either of these reasons for preferring removal pessary for sex.

As expected, sexual activity at the initial visit (at pessary fitting) was less likely with increasing patient age (OR 0.94 per year, 95% CI 0.91 – 0.97, p<0.01) and increasing Charleston comorbidity index score (OR 0.64 per one unit increase in score, 95% CI 0.44 – 0.92, p=0.02). At 3 months, sexual activity was also less likely with increasing age (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.90 – 0.96, p<0.01), increasing Charleston index (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30 – 0.72, p<0.01), and the use of any HT (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17 – 0.88, p=0.02). Reported sexual activity at 3 months was associated with daily pessary removal (OR 3.91, 95% CI 1.21 – 12.67, p=0.02), but frequent removal was not related to improved sexual function scores. In addition, sexual activity at 3 months was not related to any vaginal symptoms, hydroxyquinolone gel use, body image, or pessary satisfaction (all p>0.05).

Behaviors associated with the pessary did not significantly affect sexual function scores at 3 months after pessary fitting. The use of hydroxyquinoline gel at least once a week did not significantly affect any sexual function domain scores in sexually active or non-sexually active women. Any HT use was associated with improved condition-specific and condition impact domain scores in sexually active women at 3 months, but was not associated with PISQ-IR scores in non-sexually active women. The use of vaginal HT was not associated with any sexual function scores. The frequent removal of the pessary (at least once a day) or the removal of the pessary for sex “always” or “usually” was not associated with sexual function scores 3 months after fitting in sexually active women (all p>0.05). However, in non-sexually active women, frequent removal of the pessary was associated with improved scores on the partner-related domain.

The association and standardized beta (STB) of investigated factors on sexual function scores at 3 months for sexually active women are shown in Table 3. Pessary satisfaction was associated with improved sexual scores in multiple domains, notably the condition specific and condition impact domains. Furthermore, improved mBIS scores were associated with improved sexual function scores in multiple domains (global quality rating, condition specific, condition impact, and arousal-orgasm). Vaginal pain reported by the patient during study follow up were associated with lower condition-specific and condition impact scores, but no other vaginal symptoms during follow-up demonstrated significant relationships with sexual function scores (vaginal discharge, vaginal sores, and vaginal itching).

Table 3.

Association of patient variables with PISQ-IR domain scores at 3 months after pessary fitting for sexually active women, with standardized beta values and p-values demonstrated.

| Global Quality Rating Domain | Condition Specific Domain | Condition Impact Domain | Desire Domain | Arousal/Orgasm Domain | Partner-Related Domain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age | −0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.34 | <0.01 | 0.30 | −0.01 | <0.01 |

| BMI | −<0.01 | 0.78 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −<0.01 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.20 | <0.01 | 0.83 | <0.01 | 0.67 |

| Charleston Co-morbitidy Index | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.35 | −0.09 | 0.35 |

| Active Smoker | 0.12 | 0.67 | −0.47 | 0.19 | −0.47 | 0.21 | −0.46 | 0.27 | −0.20 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.93 |

| HT Use (Any) | −0.09 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0.048 | 0.19 | 0.30 | −0.06 | 0.71 |

| HT Use (Vaginal) | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.59 | 0.05 | −0.27 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.13 |

| Pessary Behaviors | ||||||||||||

| Frequent Pessary Removal (≥1/day) | 0.18 | 0.27 | −0.04 | 0.84 | −0.14 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 0.95 | −0.15 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.74 |

| Removal of Pessary for Sexual Intercourse | −0.25 | 0.15 | −0.18 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.71 | −0.15 | 0.30 |

| Used hydroxy-quinoline-based gel ≥1 time per week | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.08 | 0.66 | −<0.01 | 0.97 | −0.11 | 0.60 | −0.06 | 0.69 | −0.06 | 0.69 |

| Modified Body Image Score (mBIS) | ||||||||||||

| mBIS at Baseline | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.14 | −0.05 | <0.01 | −<0.01 | 0.89 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.28 |

| mBIS at 3 Months | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08 | <0.01 | −0.08 | <0.01 | −<0.01 | 0.70 | −0.03 | <0.01 | −<0.01 | 0.85 |

| Pessary Satisfaction at 3 Months | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied with Pessary | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.56 | <0.01 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.52 | <0.01 | 0.23 | 0.12 |

| Very Satisfied with Pessary | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.55 |

| Vaginal Symptoms Reported During Follow Up (2 Weeks or 3 Month) | ||||||||||||

| Vaginal Discharge | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 0.95 | −0.16 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.76 | −0.26 | 0.09 |

| Vaginal Pain | <0.01 | 0.99 | −0.48 | 0.049 | −0.59 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.70 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.18 |

| Vaginal Sores | −0.07 | 0.77 | −0.29 | 0.34 | −0.37 | 0.20 | −0.29 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| Vaginal Itching | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.11 | 0.60 | −0.23 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.25 |

The association of investigated factors on sexual function scores at 3 months for non-sexually active women at 3 months are shown in Table 4. Again, improved mBIS scores were associated with improved sexual function scores in multiple domains (global quality rating, condition specific, and condition impact). Vaginal symptoms such as pain, sores, and itching reported on follow up were associated with lower scores in various domains, although vaginal itching was associated with higher scores in the partner-related domain.

Table 4.

Association of patient variables with PISQ-IR domain scores at 3 months after pessary fitting for non-sexually active women, with standardized beta values and p-values demonstrated.

| Global Quality Rating Domain | Condition Specific Domain | Condition Impact Domain | Partner-Related Domain | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | Std β value (STB) | p-value | |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −<0.01 | 0.74 |

| BMI | −0.02 | 0.46 | −0.01 | 0.47 | −0.01 | 0.43 | <0.01 | 0.78 |

| Charleston Comorbidity Index | 0.04 | 0.81 | −0.03 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 0.84 |

| Active Smoker | −0.34 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.72 | −0.24 | 0.47 | −0.21 | 0.57 |

| HT Use (Any) | −0.07 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.82 | −0.14 | 0.59 |

| HT Use (Vaginal) | −0.83 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.14 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.65 |

| Pessary Behaviors | ||||||||

| Frequent Pessary Removal (≥1/day) | −1.15 | 0.14 | −0.24 | 0.67 | −0.55 | 0.23 | 0.99 | 0.04 |

| Used hydroxyquinoline-based gel ≥1 time per week | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.19 | −0.26 | 0.35 |

| Modified Body Image Score (mBIS) | ||||||||

| mBIS at Baseline | −0.09 | <0.01 | −0.02 | <0.01 | −0.07 | <0.01 | −<0.01 | 0.97 |

| mBIS at 3 Months | −0.12 | <0.01 | −0.07 | <0.01 | −0.09 | <0.01 | −0.02 | 0.32 |

| Pessary Satisfaction at 3 months | ||||||||

| Satisfied with Pessary | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.34 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| Very Satisfied with Pessary | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.17 | <0.01 | 1.0 |

| Vaginal Symptoms Reported During Follow Up (2 Weeks or 3 Month) | ||||||||

| Vaginal Discharge | −0.02 | 0.96 | −0.16 | 0.61 | −0.05 | 0.88 | 0.08 | 0.79 |

| Vaginal Pain | 0.14 | 0.83 | −0.95 | 0.03 | −0.29 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.44 |

| Vaginal Sores | −0.39 | 0.70 | −0.26 | 0.71 | −1.45 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.95 |

| Vaginal Itching | −1.17 | <0.01 | −0.75 | 0.02 | −0.49 | 0.12 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

Table 5 demonstrates the relationships of body image (mBIS) scores at 3 months to various factors investigated. Satisfaction with the pessary was associated with improved body image (lower mBIS scores). Body image was not significantly associated with age, but worsened (higher) body image scores were associated with increasing BMI. Interestingly, more morbid scores on the Charleston comorbidity index (higher scores on this index) were associated with improved (lower) mBIS scores. Vaginal symptoms on follow up were not associated with mBIS scores.

Table 5.

Association of patient variables with modified body image scale (mBIS) scores at 3 months after pessary fitting, with standardized beta values and p-values demonstrated.

| Std β value (STB) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Age | −0.05 | 0.11 |

| BMI | 0.19 | 0.01 |

| Charleston Comorbidity Index | −1.13 | 0.02 |

| Active Smoker | 1.63 | 0.34 |

| HT Use (Any) | −2.21 | 0.07 |

| HT Use (Vaginal) | 1.6 | 0.53 |

| Pessary Behaviors | ||

| Frequent Pessary Removal (≥1/day) | −0.36 | 0.80 |

| Pessary removed for sex | 1.51 | 0.34 |

| Randomized to hydroxyquinoline-based gel use | −1.21 | 0.26 |

| Pessary Satisfaction at 3 months | ||

| Satisfied with Pessary | −3.81 | <0.01 |

| Very Satisfied with Pessary | −3.04 | <0.01 |

| Vaginal Symptoms Reported During Follow Up (2 Weeks or 3 Month) | ||

| Vaginal Discharge | −0.81 | 0.50 |

| Vaginal Pain | 1.44 | 0.36 |

| Vaginal Sores | 3.79 | 0.06 |

| Vaginal Itching | 1.21 | 0.34 |

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of a randomized, controlled trial of new pessary users, approximately half of women using pessaries were sexually active, and sexual function remained stable from baseline to 3 months after pessary fitting, with the exception of a slight decrease in sexual function related to the sexual partner. Of note, the patient’s perception of their pelvic disorder’s impact on their sexual life, measured by the condition-specific and condition-impact domains of the PISQ-IR, did not change significantly in this study. Most sexually active pessary users in this study (70%) removed their pessary for sexual intercourse, often due to partner preferences, but removal for intercourse does not significantly impact sexual function or body image. Sexual function in this population was associated with patient factors such as body image and symptoms after pessary fitting, and both sexual function and body image were positively associated with pessary satisfaction.

Sexually active women are responsive to their partners’ opinions regarding pessary management during sexual activity. This study confirms that many women remove their pessary for sex. It should be noted that certain bulky or space-occupying pessaries require removal for vaginal intercourse, including Gellhorn, cube or doughnut pessaries. While consideration of pessary type is likely a major factor in patient decision for removal, in this study the majority of women utilized a pessary type that could be removed or left in for sexual intercourse, leaving it up to the patient and her partner to decide how to manage the pessary during sex. Furthermore, at least half of women removing the pessary for sex cited consideration of the partner as their primary reason for doing this, not pessary type or pessary comfort. It appears that partners are highly willing to share their viewpoints with the patient, as the majority (92%) of women who took their pessary out for partner considerations had been requested to do this by their partner. This concern about the pessary’s effect on the partner may account for the decrease in sexual function in the partner domain for both sexually active and sexually non-active women from baseline to 3 months. This also explains our finding that even women who do not report sexual activity demonstrated an association between improvement in partner domain scores and frequent removal of the pessary. If women are concerned about their partner’s opinion of their pessary management, employing strategies that they perceive their partners to prefer (like removal the pessary for sex) will positively affect sexual function.

Women reported that their partners expressed concern about the woman’s discomfort from the pessary during sex. This indicates that worry about a partner’s welfare during intercourse plays as large of a role for the partner as it does for the patient, and partners feel free to communicate this concern, which is encouraging from the standpoint of furthering healthy sexual relationships. Providers advising patients on pessary use should take this into consideration when discussing their pessary use and sexual activity.

Worsened pelvic floor symptoms are known to negatively impact body image and sexual function,15 and women who have relief of symptoms have improved sexual function scores.16,17 Specifically, a past study utilized the Female Sexual Function Index in sexually active women newly fitted with a pessary. In that study, improvement in sexual function was observed in the domains of desire, lubrication and satisfaction after initiation of pessary use.18 In the present study, we investigated both sexually active and non-sexually active women, and found that the condition-specific and condition impact domains of the PISQ-IR remained unchanged from baseline to 3 months. However, satisfaction with the pessary and improved body image were associated with improved sexual function scores in multiple domains, including both domains related to the patient’s perception of their pelvic floor issue (condition-specific and condition impact) and other domains as well (global quality and arousal/orgasm). Furthermore, this relationship between body image and pessary satisfaction and improved sexual health was perceived among sexually active and non-sexually active women. The fact that improved body image had a positive effect on sexual function is not surprising, and has been demonstrated in past studies.19.20 Overall, it appears that pessary users who have the most optimal sexual function are those women who have good body image and are satisfied with pessary treatment, so providers should be conscientious of these issue when performing follow-up after pessary fitting.

We found that hygiene practices employed by women in the past to optimize vaginal health, such as vaginal hormone use and hydroxyquinoline gel use, were not related to sexual function scores. Vaginal creams or gels investigated in this study, which some women may not be able to afford, access, or apply, were not related to sexual function outcomes or body image. We did demonstrate that women who have certain vaginal symptoms on follow up, such as vaginal pain or sores, have lower sexual function scores compared to women without these symptoms. Although the relationship between vaginal symptoms and sexual function could certainly be attributable to decreased pessary satisfaction or decreased well-being affecting their sexual life, it does not appear that such bothersome vaginal symptoms can be prevented by the hygiene measures investigated in this analysis. A prior publication on this data reported no benefit in BV or vaginal symptoms with the use of hydroxyquinoline gel or frequent pessary removal,10 and it appears that these measures also do not have a significant impact on sexual function or body image. This offers women reassurance that prescribed hygiene measures are not necessary for good sexual function and body image during pessary use, and women can employ pessary care strategies that fit their lifestyle.

The strengths of this study include the novel approach to looking at outcomes in pessary patients. Another strength of this study is the prospective design embedded in a large, randomized controlled trial, which diminishes bias associated with retrospective studies. Furthermore, the study population was diverse in its patient characteristics, including age, race, hormone therapy use, and frequency of pessary removal, and is representative of the wide diversity of patients that use pessaries for pelvic floor disorders. These findings on sexual function and body image can provide reassurance to a variety of pessary users that a pessary does not negatively influence sexual function or body image.

The limitations of this study include that associations between patient factors and outcomes cannot be taken as causality. For example, women who are highly concerned about their partner’s perception of the pessary may both avoid sex and remove their pessary more frequently because they believe their partner prefers this behavior, resulting in an association between partner-related sexual function and frequent pessary removal in non-sexually active women. Another limitation is that, although the PISQ-IR is a validated and meaningful measure for sexual function in this population, no known minimally important different exists for the PISQ-IR to date.11 Nonetheless, our power analysis indicates that this study should have less than a 10% risk of missing changes of half a standard deviation or greater in the PISQ-IR domain scores for sexually active women. Future investigations with larger numbers of patients may detect other variables that affect sexual function of this population. Lastly, this study only investigated sexual function three months after pessary fitting, and further changes in sexual health due to the pessary may occur after this time frame.

Conclusions

We found that sexual function is not negatively affected by pessary use with the exception of concerns related to the partner, and that women often remove a pessary for sexual intercourse and take their partner’s experience into consideration in managing their pessary. Providers should counsel women that it is expected for patients to take their needs and their partners’ needs into account when making decisions about pessary care surrounding sexual activity, and women can make their own individualized decisions about the pessary and what works well with their sexual life. As expected, satisfaction with the pessary and the absence of bothersome vaginal symptoms are associated with higher sexual function scores in women three months after pessary fitting, so providers should emphasize the importance of the patient’s overall pessary experience, follow up on all her concerns, and be mindful about how this can affect her sexual health. As sexual function is very important to women at all phases of life, this information will be key in counseling women choosing to use a pessary to treat their pelvic floor dysfunction.

Take-Home Message.

Sexual function is not negatively affected by pessary use with the exception of concerns related to the partner. Women often remove their pessary for sexual intercourse and take their partner’s experience into consideration when managing their pessary.

Acknowledgments

We thank SekiSui diagnostics for providing the OSOM BVBLUE® testing kits for the parent study at reduced cost. RG Rogers is a Chair DSMB for the Transform trial sponsored by American Medical Systems and receives royalties from Uptodate and McGraw Hill.

Footnotes

Location of study: Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA

The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Redden DT, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Markland AD. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jan;123(1):141–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Bump RC, Addison WA. A survey of pessary use by members of the American urogynecologic society. Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Jun;95(6 Pt 1):931–5. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Komesu YM, Rogers RG, Rode MA, Craig EC, Gallegos KA, Montoya AR, Swartz CD. Pelvic floor symptom changes in pessary users. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Dec;197(6):620.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komesu YM, Rogers RG, Rode MA, Craig EC, Schrader RM, Gallegos KA, Villareal B. Patient-selected goal attainment for pessary wearers: what is the clinical relevance? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 May;198(5):577.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams E, Hagen S, Maher C, Thomsson A. Cochrane Review. 2. Oxford: Cochrane Library; 2009. Mechanical devices for pelvic organ prolapse in women. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowenstein L, Gamble T, Sanses TV, et al. Changes in sexual function after treatment for prolapse are related to the improvement in body image perception. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1023–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel M, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, LaSala CA. Impact of pessary use of prolapse symptoms, quality of life, and body image. Female Pelvic Med Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;17:298. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31823a8186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brincat C, Kenton K, Pat Fitzgerald M, Brubaker L. Sexual activity predicts continued pessary use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jul;191(1):198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handa VL, Whitcomb E, Weidner AC, Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Bradley CS, Paraiso MF, Schaffer J, Zyczynski HM, Zhang M, Richter HE. Sexual function before and after non-surgical treatment for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17(1):30–35. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e318205e263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meriwether KV, Rogers RG, Rode M, Peterson SD, Gutman RE, Iglesia CB. The effect of hydroxyquinoline gel on pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis. AJOG. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.04.032. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers RG, Rockwood TH, Constantine ML, Thakar R, Kammerer-Doak DN, Pauls RN, Parekh M, Ridgeway B, Jha S, Pitkin J, Reid F, Sutherland SE, Lukacz ES, Domoney C, Sand P, Davila GW, Espuna Pons ME. A revised measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR) Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Jul;24(7):1091–103. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(2):189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1455–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farivar SS, Liu H, Hays RD. Half Standard deviation estimate of the minimally important difference in HRQOL scores? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004 Oct;4(5):515–23. doi: 10.1586/14737167.4.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos AM, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Burger CW, Paulus AT. Pelvic floor dysfunction: women’s sexual concerns unraveled. J Sex Med. 2014 Mar;11(3):743–52. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozel B, White T, Urwitz-Lane R, Minaglia S. The impact of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function in women with urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Jan;17(1):14–7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowder JL, Ghetti C, Oliphant SS, Skoczylas LC, Swift S, Switzer GE. Body image in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Questionnaire: development and validation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Aug;211(2):174.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn A, Bapst D, Stadlmayr W, Vits K, Mueller MD. Sexual and organ function in patients with symptomatic prolapse: are pessaries helpful? Fertil Steril. 2009 May;91(5):1914–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benedict C, Philip EJ, Baser RE, Carter J, Schuler TA, Jandorf L, DuHamel K, Nelson C. Body image and sexual function in women after treatment for anal and rectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2015 May 14; doi: 10.1002/pon.3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehmann V, Hagedoorn M, Gerhardt CA, Fults M, Olshefski RS, Sanderman R, Tuinman MA. Body issues, sexual satisfaction, and relationship status satisfaction in long-term childhood cancer survivors and healthy controls. Psychooncology. 2015 May 8; doi: 10.1002/pon.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]