Abstract

Patient: Male, 24

Final Diagnosis: Intestinal lymphangiectasia

Symptoms: Frequent episodes of diarrhea • recurrent infections • swelling in the lower limbs

Medication: Octreotide • MCT oils

Clinical Procedure: Endoscopic exam • Doppler ultrasound study • abdominal CT scan

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL) is a rare disease characterized by a dilatation of the intestinal lymphatics and loss of lymph fluid into the gastrointestinal tract leading to hypoproteinemia, edema, lymphocytopenia, hypogammaglobinemia, and immunological abnormalities. Iron, calcium, and other serum components (e.g., lipids, fat soluble vitamins) may also be depleted. A literature search revealed more than 200 reported cases of IL. Herein, we report our observations of a patient diagnosed with IL; we also present our conclusion for our review of the published literature.

Case Report:

A 24-year-old male was admitted to Aleppo University Hospital with the complaints of abdominal pain, headache, arthralgia, fever, and rigors. His past medical history was remarkable for frequent episodes of diarrhea, recurrent infections, and swelling in the lower limbs. In addition, he had been hospitalized several times in non-academic hospitals due to edema in his legs, cellulitis, and recurrent infections. In the emergency department, a physical examination revealed a patient in distress. He was weak, dehydrated, pale, and had a high-grade fever. His lower extremities were edematous, swollen, and extremely tender to touch. The overlying skin was erythematous and warm. Moreover, the patient was tachycardic, tacypneic, and moderately hypotensive. The patient was resuscitated with IV fluids, and Tylenol was administered to bring the temperature down. Blood tests showed anemia and high levels of inflammatory markers. The patient’s white blood cell count was elevated with an obvious left shift. However, subsequent investigations showed that the patient had IL. Suitable diet modification plans were applied as a long-term management plan.

Conclusions:

IL is a rare disease of challenging nature due to its systematic effects and lack of comprehensive studies that can evaluate the effectiveness of specific treatments in a large cohort of patients. Medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oils and diet modification strategies are effective in reducing the loss of body proteins and in maintaining near-normal blood levels of immunoglobulins. However, octreotide and MCT oils had no proven role in reducing lymphedema in our patient.

MeSH Keywords: Lymphangiectasis, Intestinal; Octreotide; Protein-Losing Enteropathies; Cellulitis

Background

Intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL) is a rare disorder characterized by impaired intestinal lymphatic drainage due to primary ectasia, diffuse or localized, of the intestinal lymphatic vessels, or as a result of secondary impacts on the normal lymph circulation, such as heart diseases and retroperitoneal lymph node enlargements [1]. Regardless of the cause, the pathogenesis of IL involves a dilation of the intestinal lymphatic vessels and an increase in the interstitial pressure, leading to lymph fluid leakage into the intestinal lumen. This outflow of lymph fluid decreases the plasma oncotic pressure due to a lack of proteins and gamma-globulins in the plasma. In addition, fat, lymphocytes, electrolytes, and fat soluble vitamins can be depleted [2,3].

The age of disease onset is variable. Although the diagnosis was established, in multiple studies, in infants. But IL has been observed in older age groups. It has been reported that the mean age of disease onset is twelve years. No etiological causes for IL have been identified, and genetic etiology is not clearly defined. Almost all the reported cases are of sporadic origin and familial stories of IL in first- or second-degree relatives are rarely reported [4]. Prevalence is unknown and disease distribution around the world is poorly researched due to the rareness of the disease.

The symptoms of IL are variable depending on its severity. The classical symptoms are bilateral or unilateral lower limb edema and intermittent diarrhea. Some patients develop steatorrhea; in other cases, an accumulation of fluids in body cavities resulting in pleural effusion or ascites has been reported [5,6]. The main patient complaints are abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, intermittent diarrhea and steatorrhea, chronic fatigue, weakness, weight loss, and inability to gain weight.

IL is a challenging disease due to its physical characteristics and its psychological effects on the patients and their families. Diet modification plans, medium-chain triglycerides (MCT), octreotide, antiplasmin, and surgical procedures have been introduced as management choices for the disease [7–10].

Here, we present a case of a patient with IL. This patient was followed, closely, for more than three years. In addition, we searched the literature looking for similar cases of IL. The purpose of this report is two-folds: to present our case study and IL management plan and present the conclusions from an investigation of the literature.

Case Report

A 24-year-old male was admitted to Aleppo university Hospital (AUH), in 2010, with the complaints of abdominal pain, headache, arthralgia, fever, and rigors. The patient stated that he had, since infancy, intermittent episodes of foul-smelling diarrhea. These episodes were accompanied by abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The patient was suffering from intractable bilateral swelling in the lower limbs, more prominent in his left leg. This swelling was responsible for restricting his daily life activities.

The current hospitalization was one in a series of admissions to a non-academic hospitals, inside and outside the country. These admissions were for multiple reasons. Reviewing the patient’s medical history revealed that recurrent infections were the most common cause for all of his previous hospitalizations. In the emergency department, a physical examination revealed a distressed patient with an ill appearance. He was weak, dehydrated, pale, and had a high-grade fever of 39.6°C (103.2°F). The patient was lying supine on the exam table with his legs drawn down, arms on his abdomen, and he was shivering and staring with an anxious facial expressions and eyes that were filled with tears. Moreover, the patient was dyspneic with a respiratory rate of 17 beats/minute and without cyanotic hue; his oxygen saturation was 92%. The patient was tachycardic (pulse rate, 125 beats/minute), and moderately hypotensive (blood pressure 97/60 mm Hg).

The patient’s lower extremities were severely edematous, and extremely tender to touch. The overlying skin was erythematous and warm. The redness of the skin extended from the left popliteal area to the scrotum, which was enlarged but not tender to palpation. The skin covering the scrotum had changed to a very thick and hard skin mass. Further investigation revealed that the patient had an insect bite on the top of his left foot, one week ago.

The patient was resuscitated with IV fluids. Tylenol was infused to bring his temperature down, and to control pain. Blood tests in the emergency department showed a high C-reactive protein (CRP) level and an elevation in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). White blood cell count was 18,500 per mm3 with 85% neutrophilia. Hemoglobin was 10.3 g/dL and the hematocrit was 31%. The patient was admitted to the general internal medicine department in AUH for further investigations and management.

In the general internal medicine department, the management plan was applied immediately, including IV fluids, empiric antibiotic therapy, and analgesics. Additional blood samples were drawn for further laboratory testing, blood culture, and antibiotic sensitivity tests. Table 1 presents a summary of the laboratory test results.

Table 1.

Results of blood tests.

| Blood test | Results | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBCs | WBC and differential | 18,500 (N 85%–L 5%) | 5–10×1,000/mm3 |

| HGB | 10.3 | 12–18 g/dL | |

| HCT | 31 | 37–52% | |

| PLT | 322 | 150–450×109/L | |

| Inflammatory markers | ESR | 43/72 | mm/L |

| CRP | 32 | mg/L | |

| RFTs | Urea | 45 | 7–20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.7 | 0.6–1.2 mg/dL | |

| Electrolytes | Sodium | 135 | 135–145 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 3.8 | 3.5–5.5 mmol/L | |

| Calcium | 7.9 | 8.5–10.2 mg/dL | |

| Magnesium | 1.7 | 1.5–2.5 mEq/L | |

| LFTs | ALT/AST | 45/35 | 7–56 unit/L |

| PT | 13.8 | Seconds | |

| INR | 1.1 | – | |

| Chemistry | ALP | 110 | 44–147 IU/L |

| Bilirubin (total/direct) | 1/0.8 | 0.3–1.9 mg/dL | |

| Total protein | 3.2 | 6–8 g/dl | |

| Albumin | 2.1 | 3.5–5.5 g/dL | |

| Immunology | ANA | Negative | <1/0 IU |

| Anti-dsDNA | Negative | <1/0 IU | |

| IG | IGG | 35 | 650–1,500 mg/dL |

| IGA | 10 | 80–350 mg/dL | |

| IGM | 14 | 45–250 mg/dL | |

| IGE | 2 | 150–1,000 UI/mL | |

| Thyroid function test | TSH | 1.6 | 0.3–5.0 U/mL |

| FT4 | 1.1 | 0.8–2.8 ng/dL | |

| Lipid profile | Cholesterol | 79 | 180–200 mg/dL |

| LDL | 80 | 100–129 mg/dL | |

| HDL | 42 | 35–65 mg/dL | |

| TG | 35 | 150–200 mg/dl |

CBC – cell blood count; WBC – white blood cell; HGB – hemoglobin; HCT – hematocrit; PLT – platelet; ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP – C-reactive protein; RFT – renal function test; LFT – liver function test; ALT – alanine aminotransferase; AST – aspartate aminotransferase; ALP – alkaline phosphate; PT – prothrombin time; INR – international normalized ratio; ANA – antinuclear antibody; Anti-dsDNA – anti-double stranded DNA; IG – immunoglobulin; LDL – low-density lipoprotein; HDL – high-density lipoprotein; TG – triglycerides.

Doppler ultrasound study of the lower limbs and scrotum was performed and showed a diffuse thickening, increasing the echogenicity of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. These findings were accompanied by hypoechoic strands of fluids that extended between the hyperechoic fat and the underlying connective tissues. A characteristic “cobblestone” appearance was observed along the left leg. The veins in the left leg were non-compressible and Doppler flow was clearly sufficient. The vessels in the scrotum area were intact and the blood supply to the testes was adequate. An accumulation of scrotal fluids was observed bilaterally, extending slightly to the penis.

Abdominal sonogram revealed an edematous gallbladder wall and large bowel loops with markedly thickened walls. A slight amount of ascetic fluid was observed in the peritoneal cavity.

Three days later, when the patient clinically stabilized, further investigational procedures were planned to study the swelling of the lower limbs. The CT scan was very useful in identifying dilated intestinal loops and a diffuse thickening of the intestinal walls, as well as mesenteric edema. The CT scan showed that the circumferential thickening of the small bowel wall was enlarged (1.5–2 cm).

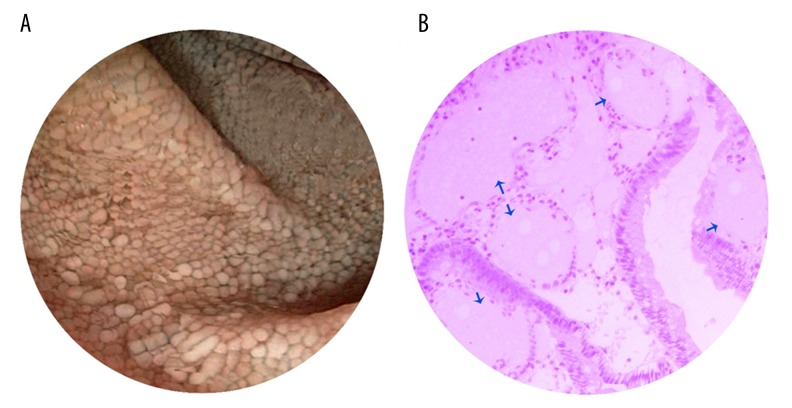

One week later, an endoscopic examination was performed, which was significant for mucosal changes and white spots and nodules (dilated lacteals) (Figure 1A). Multiple biopsies were obtained for further histological examinations, which showed a characteristic dilatation of the enteric lymph vessels in the mucosal and submucosal layers without any evidence of inflammation. The histological examination was suggestive of IL (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic and histological findings. Mucosal changes showing white spots and nodules (dilated lacteals) in the duodenum (A) and dilated lymphatic vessels (blue arrows) (B).

The results of our investigations, integrated with the patient’s clinical picture, were suggestive of an IL associated with cellulites in the left lower limb.

Three weeks later, the patient was totally recovered; he was discharged home and scheduled for a routine follow-up visits in the internal medicine clinic at AUH.

The patient was followed for more than three years. His long-term management plan was designed to primarily educate the patient and his parents about the specifics of his disease. In addition, the management included dietary modifications, routine screening tests, and some medications to control his chronic diarrhea. The patient was advised to use a compression stocking, raise his leg while in a supine position, and to do routine massages to the lower limbs.

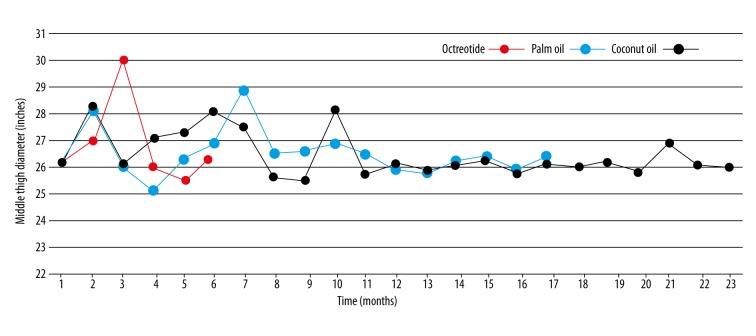

While the patient was under observation in the hospital, octreotide was applied subcutaneously, and we continued this treatment with a slow-release formulation for a period of six months.

The most important part of our management plan was diet modifications. The nutritionist in our clinic had educated the patient to substitute the long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) in his food with medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs). Due to its availability and cheapness, the patient started to consume palm oil as a per-oral morning load and in his daily meals. He followed the palm oil diet for seventeen months. The palm oil diet was replaced later with a coconut oil diet. See (Figure 2) for clinical features of IL in our patient.

Figure 2.

Clinical findings of intestinal lymphangiectasia. The patient showing yellow scab on the top of the nose due to infection (A); Lower limb edema extends to the thigh (B); Scrotal skin thickening (C); Warts (yellow arrows) on the dorsal part of the right foot (D); Edema after discharge from the hospital (E); Edema after two years of management (F).

In order to track the effectiveness of the previously mentioned procedures on the amount of swelling in the lower limb, we measured the diameter of his leg and the middle part of his thigh. The anatomical landmarks for these measures were the middle part of the thigh, the lateral malleolus of the fibula, and the medial malleolus of the tibia. We recorded these measurements during every visit and at the same time of day (i.e., the patient was scheduled at 13:00 PM and his measurements were taken at 13:30 PM).

Practically speaking, we have never seen any significant improvement in the size of the swelling in the lower limb or in the scrotal area. It seems that the regression of edema in the lower leg was slightly better when coconut oil was applied, but this change was trivial overtime. Notably, the edema was less in the early morning and greater in the evening. The mechanical maneuvers (e.g., raising the leg during sleep, massages) were temporarily effective in reducing the edema size.

The diet modification plan was of great benefit in preventing further accumulation of fluids, controlling the loss of enteric proteins, and in preventing susceptibility to infectious agents. The patient was never rehospitalized for any reason up to the time of drafting this article. MCT oils had no important effects on edema size in the long-term management plan for our patient.

Discussion

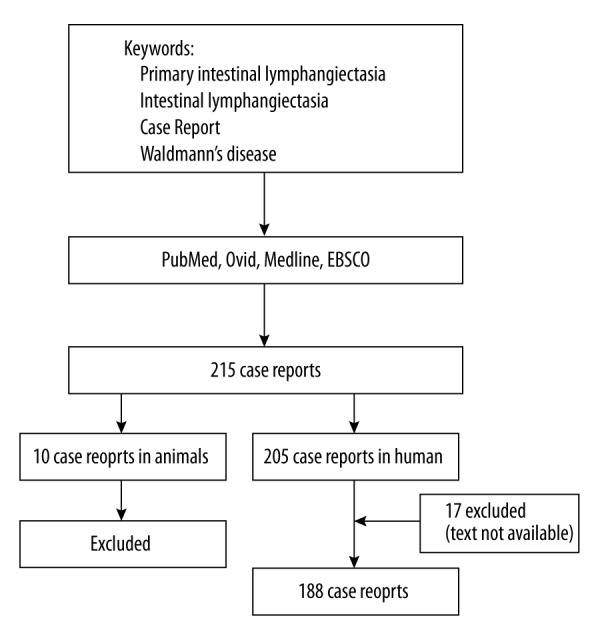

We performed our literature search in PubMed using the keywords “primary intestinal lymphangiectasia, intestinal lymphangiectasia, Waldmann’s disease, case report”. Feeding the same words into Ovid, Medline, and EBSCO led to the same results. Two hundred and fifteen articles were identified. Two of the co-authors reviewed the literature separately, and they matched the results. According to our search, the first case report of IL was published in 1965 [11]. Ten articles described IL in animals (nine articles were for a diagnosis of IL in dogs and one in a horse. One paper was a pharmaceutical experiment on a guinea pig [12]). The remaining 205 articles described IL in humans.

The original text was not available for seventeen articles, so they were excluded from our review. The final number of articles included in our review was 188 studies in humans. Figure 3 presents a flowchart for our literature search.

Figure 3.

Flowchart for literature search showing the included and excluded articles.

The articles were classified as follow:

Articles described a single case report and its clinical course in a patient.

Articles presented multiple case reports and its clinical manifestations in each patient.

Articles studied an association between IL and other etiologies.

Articles dedicated their attention to the complications of IL.

The role of specific treatments in the management of IL was presented in multiple studies; these treatments were: octreotide, MCT oil, low fat diet plans, and anti-plasmin.

Some studies were interested in an investigational means to establish the diagnosis of IL.

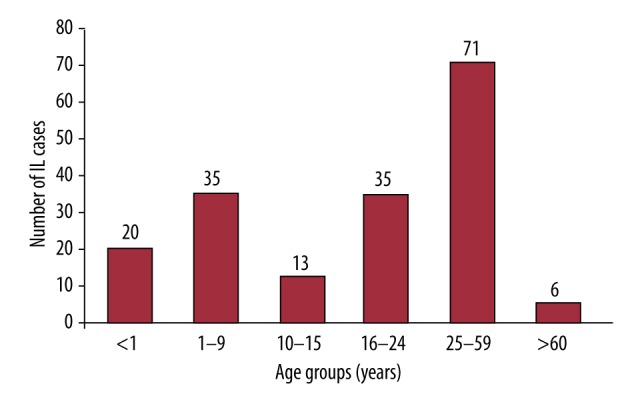

Literature search revealed that the age at diagnosis was widely variable. While some cases were diagnosed early in life, others were detected later in life. Age was clearly elucidated in 180/188 case reports. Figure 4 present the number of case reports in each age group. The total number of male and female patients included in the reported cases (178/188) was 100 males and 78 females. Sporadic IL cases were more prominent; almost 90% of the reported IL cases were of sporadic origin and the rest were of familial susceptibility with a genetic basis.

Figure 4.

Column chart showing the number of reported case reports within each age group.

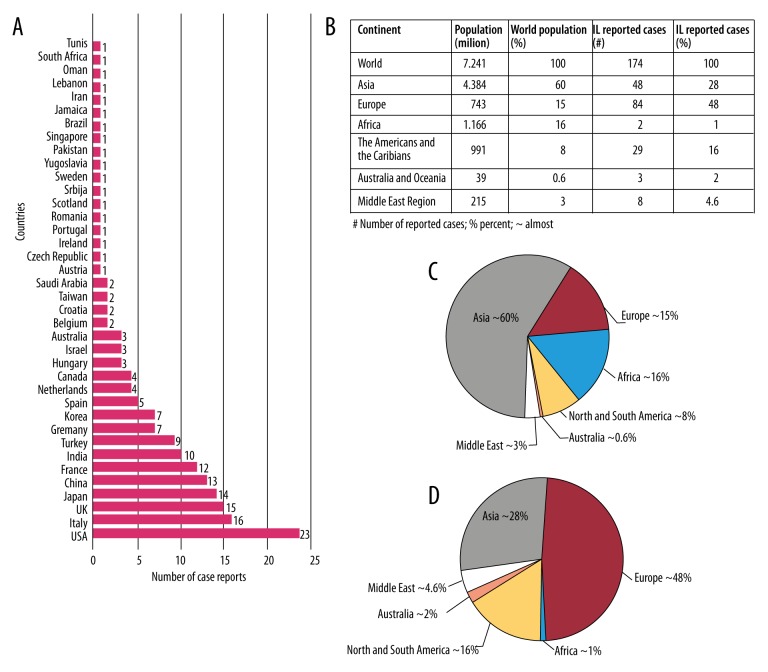

We were able to detect the patient’s nationality in 174/188 articles. The largest number of reported cases were from Europe: 84/174 case reports (Italy 16, UK 15, France 12, Turkey 9; other European countries had less than five cases per country). We found 48/174 case reports for patients from Asia (Japan 14, China 13, India 10, Korea 7; other Asian countries had less than two cases per country). In North and South America, the United States had the largest number of reported cases, with 23/174. Three cases were reported from Australia, two from Africa and 8/174 were from the Middle East region.

Taking into account the regional and continental population totals, the largest number of reported cases of IL were from countries in Europe, particularly Italy, comprising approximately 50% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Regional and continental distribution of intestinal lymphangiectasia. The number of reported case reports by the country of disease origin (A); Regional and continental population and the number of reported IL cases (B); Pie chart showing the percent of population in every region and continent (C); Pie chart showing the percent of reported IL cases in every region and continent (D).

Although in our literature review we cannot point directly to the reason(s) behind the high number of IL cases reported in Europe, on the one hand, we suspect that the medical procedures applied in the countries of the European Union, with regards to health insurance and medical care, covered a more general population, and as a result, discovering and reporting a higher number of rare medical conditions should be expected.

On the other hand, considering the population of Asia in 2015 was almost more than 60% of the world population, and the small number of reported cases from Asian countries, this makes us think that other factors could be the cause of the high number of the reported cases of IL in Europe; naturally, the possibility of genetic factors comes to mind.

In our review we found that a large number of articles (87/188) reported an association between IL and other diseases. Table 2 is a summary of diseases associated with IL, which suggests that a high number of medical cases associated with IL may be due to hypoalbuminemia and lymphopenia and their widespread systemic consequences.

Table 2.

Medical conditions associated with or complicated by intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL).

| PMID* | IL associated with or complicated by | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5645698 | Nephrotic syndrome | De Sousa JS et al. | 1968 |

| 4177544 | Immunoglobulin A deficiency | Eisner JW et al. | 1968 |

| 1249692 | Noonan syndrome | Herzog DB et al. | 1976 |

| 604991 | Small bowel lymphoma | Ward M et al. | 1977 |

| 512793 | Colonic polyps | Parsons HG et al. | 1979 |

| 6401772 | Macroglobulinemia | Harris M et al. | 1983 |

| 3984978 | Aplasia cutis congenital | Bronspiegel N et al. | 1985 |

| 3971596 | Thymic hypoplasia | Sorensen RU et al. | 1985 |

| 4018652 | Impaired splenic function | Foster PN et al. | 1985 |

| 4065700 | Chylous ascites | Duhra PM et al. | 1985 |

| 3782656 | Pleural effusion | Lester LA et al. | 1986 |

| 3960333 | Vitamin E-deficient spinocerebellar syndrome | Gutmann L et al. | 1986 |

| 3266226 | Epileptic episodes | Katou N et al. | 1988 |

| 3195550 | Systemic sclerosis | van Tilburg AJ et al. | 1988 |

| 2624276 | Facial anomalies and mental retardation | Hennekam RC et al. | 1989 |

| 2220736 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Edworthy SM et al. | 1990 |

| 8335455 | Constrictive pericarditis | O’Sullivan T et al. | 1993 |

| 8374252 | Acute jejunal ileus | Lenzhofer R et al. | 1993 |

| 8533807 | Zellweger cerebrohepatorenal syndrome | Erdem G et al. | 1995 |

| 8970209 | Oral manifestations | Ralph PM et al. | 1996 |

| 9932170 | Small bowel lymphoma | Gumà J et al. | 1998 |

| 10403358 | Gelatinous transformation of the bone marrow | Marie I et al. | 1999 |

| 11841381 | Xanthomatosis, vaginal lymphorrhoea | Karg E et al. | 2002 |

| 12124738 | Hennekam syndrome | Forzano F et al. | 2002 |

| 15531848 | Incontinentia pigmenti achromians | Riyaz A et al. | 2004 |

| 16129004 | Enamel hypoplasia of the primary dentition | Arrow P et al. | 2005 |

| 16174162 | Breast edema | Goktan C et al. | 2005 |

| 16407384 | Yellow nail syndrome | Danielsson A et al. | 2006 |

| 16123987 | Neuroblastoma | Citak C et al. | 2006 |

| 17321261 | Abdominal mass | Rao R et al. | 2007 |

| 17514630 | Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Kalman S et al. | 2007 |

| 17354127 | Gastrointestinal bleeding | Stovicek J et al. | 2007 |

| 18431016 | Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I | Makharia GK et al. | 2007 |

| 19864203 | Vitamin D deficiency | Lu YY et al. | 2009 |

| 20567835 | Castleman’s disease | Jeon CJ et al. | 2010 |

| 21086252 | Duodeno-jejunal polyposis | Hirano A et al. | 2010 |

| 20812055 | Digital clubbing | Wiedermann CJ et al. | 2010 |

| 21947159 | Histiocytosis X | Hui CK et al. | 2011 |

| 22616341 | Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III | Choudhury BK et al. | 2011 |

| 22366835 | Infantile systemic hyalinosis syndrome | Alreheili K et al. | 2012 |

| 25276285 | Liver fibrosis | Licinio R et al. | 2014 |

| 26405709 | Anemia | Balaban VD et al. | 2015 |

| 26217101 | Generalized warts | Lee SJ et al. | 2015 |

PMID – PubMed identifier.

In 37/188 articles, authors introduced diagnostic procedures and radiological findings that can be used to evaluate and diagnose IL, and 15/188 articles shed light on the secondary causes of IL. Table 3 presents a summary of diseases complicated by IL in their clinical course; 30/188 articles described classic cases of IL with all its known clinical features.

Table 3.

Secondary causes for IL.

| PMID | Disease | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7463809 | Myxedema heart | Munakata Y et.al | 1980 |

| 7247748 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Pereira AS et.al | 1980 |

| 3608736 | Radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Rao SS et.al | 1987 |

| 17632262 | Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia | Pratz KW et.al | 2007 |

| 20801422 | Primary peritoneal carcinoma | Steines JC et.al | 2010 |

| 21092952 | Multiple myeloma | Bhat M et.al | 2011 |

| 21837942 | Primary hypoparathyroidism | Koçak G et.al | 2011 |

| 23591283 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Patel KV et.al | 2013 |

Our review found 35/188 articles that described management plans. In particular, octreotide was discussed in 10/35 articles [13–21], antiplasmin in 3/35 [22–24], corticosteroids in 2/35 [25,26], and surgical procedures in 7/35; the rest of the articles (13/35) described a diet modification plan and the role of MCT oil in the management of IL [27]. In almost all the previous studies, the prognosis was ambiguous due to short time periods of the reported management plans. Octreotide was only effective in blocking diarrheal episodes and for correcting hypoalbuminemic states. Table 4 presents a summary of studies that discussed the role of octreotide in the management of IL.

Table 4.

Octreotide management in IL.

| PMID | Age | Gender | Indication | Outcome | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7783555 | 38 | M | Hypoalbuminemia | Improvement# | Bac DJ et al. | 1995 |

| 11227670 | 21 | M | Hypoalbuminemia | Improvement | Kuroiwa G et al. | 2001 |

| 12924644 | 27 | F | Generalized hydrops | May be effective | Klingenberg RD et al. | 2003 |

| 15506669 | 25 | F | Severe edema and diarrhea | Improvement | Filik L et al. | 2004 |

| 15565209* | – | – | Severe edema | No improvement | Makhija S et al. | 2004 |

| 15373983 | – | – | Edema, diarrhea | Improvement | Balboa A et al. | 2004 |

| 21768882 | 15 | M | Hypoalbuminemia | Improvement | Altit G et al. | 2012 |

| 23555496 | 63 | M | Edema, diarrhea | Improvement | Suehiro K et al. | 2012 |

| 23180957 | Baby | – | Edema | Improvement | Al Sinani S et al. | 2012 |

Improvement: Correction of hypoalbuminemia;

octreotide was tested to treat intestinal lymphangiectasia in guinea pig model.

In our patient’s case, after more than three years of a careful management plan and persistent follow-up, it was clear that octreotide, diet modification, and MCT oils were unable to eliminate the edema. Using MCT oils over more than three years did not show any important improvement in the edema size (Figure 6). However, these management approaches were of benefit in restricting further extension of the edema, although they were unable to eradicate the existence of the original presenting edema. Most likely, this is related to the fact that MCT oils and octreotide are unable to affect already-extended lymphatic vessels. Notably, the only benefit observed for the use of MCT oils is that it, probably, played a role in maintaining the immune system function against various infectious agents. This is in part due to the fact that these oils can help in preventing the loss of enteric proteins.

Figure 6.

The changes observed in edema size under management over time. Line chart showing the change in edema size over time following management with octreotide (red); palm oil (blue); coconut oil (black). The treatments were not applied simultaneously, but overlapped for easy interpretation of the data.

Conclusions

Low-fat diet plans, light exercises, massages, and medium-chain triglycerides (MCT), such as coconut and palm oils, can help to prevent further extension of edema in patients with (IL). It seems that MCT oils are an excellent choice to protect against further loss of body proteins, and this can help to boost the immune system against various infections agents. It is very important to note that octreotide and MCT oils had no effect on reducing lymphedema in our patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient for his consent.

Footnotes

Statements and declarations regarding conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References:

- 1.Vignes S, Carcelain G. Increased surface receptor fas (CD95) levels on CD4+ lymphocytes in patients with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(2):252–56. doi: 10.1080/00365520802321220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann’s disease) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3 doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-5. 5-1172-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: Case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):43–49. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.561. quiz 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malek NP, Ocran K, Tietge UJ, et al. A case of the yellow nail syndrome associated with massive chylous ascites, pleural and pericardial effusions. Z Gastroenterol. 1996;34(11):763–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lester LA, Rothberg RM, Krantman HJ, Shermeta DW. Intestinal lymphangiectasia and bilateral pleural effusions: Effect of dietary therapy and surgical intervention on immunologic and pulmonary parameters. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78(5 Pt 1):891–97. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin CC, Garcia AF, Restrepo JM, Perez AS. Sucessful dietetic-therapy in primary intestinal lymphangiectasia and recurrent chylous ascites: A case report. Nutr Hosp. 2007;22(6):723–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuroiwa G, Takayama T, Sato Y, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia successfully treated with octreotide. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(2):129–32. doi: 10.1007/s005350170142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleisher TA, Strober W, Muchmore AV, et al. Corticosteroid-responsive intestinal lymphangiectasia secondary to an inflammatory process. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(11):605–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903153001106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alfano V, Tritto G, Alfonsi L, et al. Stable reversal of pathologic signs of primitive intestinal lymphangiectasia with a hypolipidic, MCT-enriched diet. Nutrition. 2000;16(4):303–4. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett DS, Large SR, Rees GM. Pleurectomy for chylothorax associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia. Thorax. 1987;42(7):557–58. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.7.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadell EJ, Dame RW, Wolford JL. Chronic hypoalbuminemia and edema associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia. JAMA. 1965;194(8):917–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makhija S, von der Weid PY, Meddings J, et al. Octreotide in intestinal lymphangiectasia: Lack of a clinical response and failure to alter lymphatic function in a guinea pig model. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18(11):681–85. doi: 10.1155/2004/176568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altit G, Patel H, Morinville VD. Octreotide management of intestinal lymphangiectasia in a teenage heart transplant patient. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54(6):824–27. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31822d2dd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuroiwa G, Takayama T, Sato Y, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia successfully treated with octreotide. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(2):129–32. doi: 10.1007/s005350170142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filik L, Oguz P, Koksal A, et al. A case with intestinal lymphangiectasia successfully treated with slow-release octreotide. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(10):687–90. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klingenberg RD, Homann N, Ludwig D. Type I intestinal lymphangiectasia treated successfully with slow-release octreotide. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(8):1506–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1024707605493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bac DJ, Van Hagen PM, Postema PT, et al. Octreotide for protein-losing enteropathy with intestinal lymphangiectasia. Lancet. 1995;345(8965):1639. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suehiro K, Morikage N, Murakami M, et al. Late-onset primary intestinal lymphangiectasia successfully managed with octreotide: A case report. Ann Vasc Dis. 2012;5(1):96–99. doi: 10.3400/avd.cr.11.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Sinani S, Rawahi YA, Abdoon H. Octreotide in hennekam syndrome-associated intestinal lymphangiectasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(43):6333–37. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balboa A, Perello A, Mearin F. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: Effectiveness of treatment with slow-release octreotide. Med Clin (Barc) 2004;123(8):319. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballinger AB, Farthing MJ. Octreotide in the treatment of intestinal lymphangiectasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10(8):699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mine K, Matsubayashi S, Nakai Y, Nakagawa T. Intestinal lymphangiectasia markedly improved with antiplasmin therapy. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(6):1596–99. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heresbach D, Raoul JL, Bretagne JF, Gosselin M. Intestinal lymphangiectasia: Lack of efficacy of antiplasmin therapy? Gastroenterology. 1991;100(4):1152–53. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen SA, Diuguid DL, Whitlock RT, Holt PR. Intestinal lymphangiectasia and antiplasmin therapy. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(6):2193. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hargrove MD, Jr, Mathews WR, McIntyre PA. Intestinal lymphangiectasia with response to corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med. 1967;119(2):206–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleisher TA, Strober W, Muchmore AV, et al. Corticosteroid-responsive intestinal lymphangiectasia secondary to an inflammatory process. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(11):605–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903153001106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alfano V, Tritto G, Alfonsi L, et al. Stable reversal of pathologic signs of primitive intestinal lymphangiectasia with a hypolipidic, MCT-enriched diet. Nutrition. 2000;16(4):303–4. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]