Abstract

Objective

Little is known about recent trends in marijuana use disorders among adolescents in the United States. We analyzed trends in the past-year prevalence of DSM-IV marijuana use disorders among adolescents, both overall and conditioned on past-year marijuana use. Potential explanatory factors for trends in prevalence were explored.

Method

We assembled data from the adolescent samples of the 2002–2013 administrations of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (N=216,852; ages 12–17). Main outcome measures were odds ratios describing the average annual change in prevalence and conditional prevalence of marijuana use disorders, estimated from models of marijuana use disorder as a function of year. Post hoc analyses incorporated measures of potentially explanatory risk and protective factors into the trend analyses.

Results

A decline in the past-year prevalence of marijuana use disorders was observed (OR=0.976 per year; 95% CI: 0.968, 0.984; p<.001). This was due to both a net decline in past-year prevalence of use and a decline in the conditional prevalence of marijuana use disorders. The trend in marijuana use disorders was accounted for by a decrease in the rate of conduct problems among adolescents (e.g., fighting, stealing).

Conclusion

Past-year prevalence of marijuana use disorders among US adolescents declined by an estimated 24% over the 2002–13 period. The decline may be related to trends toward lower rates of conduct problems. Identification of factors responsible for the reduction in conduct problems could inform interventions targeting both conduct problems and marijuana use disorders.

Keywords: Marijuana, addiction, adolescence, epidemiology, externalizing

INTRODUCTION

The social and policy landscapes governing use, possession, and availability of marijuana by adults in the United States have shifted markedly in the past two decades. The implementation of state-level decriminalization, medical, and recreational legalization policies has raised concerns about direct or indirect policy influences on adolescent marijuana use. Direct effects might occur if teenagers have easier access through diversion of medical or recreational marijuana purchased by adults.1 Relaxed policies might act indirectly by causing adolescents to view marijuana use as less risky and more socially acceptable, thereby leading to higher prevalence of use.2,3 Despite these changes in policy and associated changes in social norms,4 the prevalence of adolescent marijuana use has been relatively stable over the past 10 to 15 years.5,6 It is less clear whether there have been changes in rates of problem use or of marijuana use disorders during this period. The distinction between experimental use and abuse or dependence is important because there may be many individual-level factors that confer liability to problem use among adolescent marijuana users.7–9 With this in mind, the objective of this study was to examine recent trends in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders among US adolescents. To our knowledge, no such studies have been previously conducted.

Our specific objectives were to examine trends in the past-year prevalence of DSM-IV marijuana use disorders (abuse or dependence), both overall and conditioned on past-year use, among adolescents over the period 2002–2013. We also analyzed trends in marijuana use over the same period in order to parse the trends in risk for marijuana use disorders into those stemming from trends in use and those related to changes in the conditional prevalence. Finally, we examined secular trends in a number of risk and protective factors and whether they might explain trends in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders. We present results of analyses that utilize data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), an annual survey representative of the household-dwelling population of the United States that has yielded year-to-year comparable estimates of drug use, abuse, and dependence since 2002.10,11

METHOD

Survey Overview and Sample

Analyses presented here utilized the adolescent subsamples of the NSDUH, which includes participants ages 12–17, from years 2002 through 2013. The year 2002 was chosen as the beginning of the observation window because data from earlier years are not comparable to the most recent surveys due to methodological changes in NSDUH procedures. The most recent year for which public use data was available at the time of writing was 2013. NSDUH data were obtained from the Interuniversity Consortium for Social and Political Research.12 The NSDUH is an ongoing survey of the civilian non-institutionalized population of the United States, ages 12 and over, including those living in group-quarters such as college dormitories and shelters.10 The survey is overseen by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and is currently contracted through RTI, International. Briefly, the survey utilizes multistage probability sampling from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Adolescents and young adults are oversampled, with one-third of the samples drawn from each of three age groups: 12–17, 18–25, and 26+. The interview is conducted in dwelling units by RTI fieldworkers with drug use questions and other sensitive items administered by audio-computer assisted self-interview to maximize privacy and confidentiality. Detailed methods are available through SAMHSA.13 The combined 2002–2013 yielded a sample of 216,852 adolescent participants.

Variables

The primary variables of interest were past-year marijuana use and past-year DSM-IV marijuana use disorders; i.e., the proportion of individuals meeting DSM-IV criteria for marijuana abuse or marijuana dependence. We focus on DSM-IV because it was the diagnostic standard throughout the observation period, though it has since been superseded by DSM-V.14 Furthermore, despite substantial overlap between DSM-IV and DSM-V criteria, DSM-IV did not assess craving,15 which is a new addition to DSM-V, and so that criterion was not operationalized in the NSDUH interview. Past-year marijuana use was queried of individuals who reported lifetime use. A module assessing past-year DSM-IV marijuana abuse and dependence was administered to individuals who reported using marijuana on 6 or more days in the prior year.16

Covariates in demographics-adjusted models of trends included sex, age, and race, which were also used as stratification variables. Race was recoded into four groups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other non-Hispanic. Age was treated as a categorical variable for descriptive analyses. Two broad age categories were defined: 12–14, 15–17, and a number of trend analyses were stratified by these age categories.

A series of variables operationalizing risk and protective factors that might explain changes in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders were examined. Scores for each variable were constructed from items from the NSDUH Youth Experiences module using item response theory (IRT). Risk factors included frequency of arguments and fights with parents, number of conduct problems, and a measure of permissive parental attitudes toward alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs (as perceived by the child). Protective factors included measures of positive attitudes toward school, parental monitoring, frequency of affirmation by parents, number of activities outside of school, exposure to drug education programs, and religious commitment. More details about the selection and construction of these variables are given in Supplement 1 (available online); items comprising the constructs are listed in Table S1 (available online).

Statistical Procedures

All statistical analyses were carried out in SAS version 9.4, and utilized survey weights and procedures that account for the complex sample design of the NSDUH in variance estimation. Trends were analyzed using logistic regression. The most basic analyses simply modeled marijuana use disorder (or marijuana use) as a function of year, coded as a continuous variable. This analysis yields an estimated odds ratio that describes the average change in odds for marijuana use disorders per year. We also used the estimated intercepts from the logistic regression analysis to calculate fitted values of prevalence for years 2002 and 2013, respectively. Demographic covariates were incorporated into some models to estimate “partially adjusted” trends. This label was chosen to differentiate from fully adjusted models which incorporated risk and protective factors; these analyses are described more fully below. Stratified analyses were also conducted to examine the degree to which trends varied by sex, race, and age group; these analyses did not incorporate other covariates.

Post hoc analyses focused on the degree to which trends in marijuana use disorders were related to secular trends in the risk and protective factors described above. Specifically, we were interested in the degree to which the magnitude of the trend estimate was attenuated after adjustment for these factors (which we refer to as the “attenuation effect”). To identify potential explanatory factors, we used linear regression to model trends in each risk/protective factor score as a function of year. We considered risk factors that decreased over time, or protective factors that increased over time to be candidates that might be related to the trends in marijuana use disorders. Then, we constructed a series of models predicting marijuana use disorder, while adjusting for candidate explanatory factors. Each of those models included year as the primary independent variable of interest, demographic covariates, and one of the risk/protective factors as a potential explanatory variable.

After determining that the “conduct problems” variable had the largest attenuation effect on the trend estimate, the statistical significance of the attenuation was estimated using bootstrap resampling procedures. Specifically, we used SAS “proc surveyselect” to construct 1,000 resamples of the original NSDUH sample. For each resample, we generated estimates of (a) the partially adjusted trend (controlled for demographics only) and (b) the fully adjusted trend, controlling for demographics and the conduct problem score. Within each resample, the difference between the partially and fully adjusted trend estimates was calculated (i.e., the attenuation effect). The 95% CIs for the difference estimate were taken from the 5th and 95th percentiles of the array of bootstrapped estimates.

RESULTS

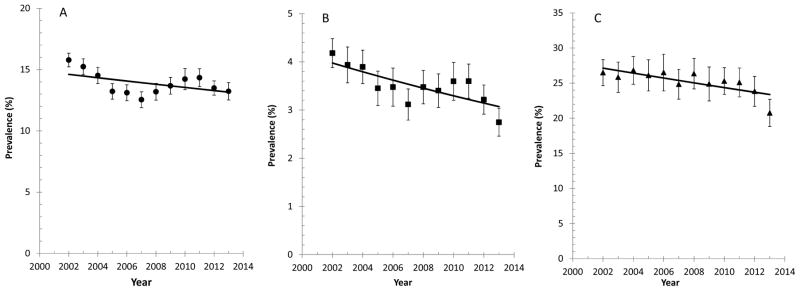

A demographic description of the sample, as well as prevalences of past-year marijuana use, marijuana use disorder, and marijuana use disorders among past-year users is provided in Table S2 (available online). Annual prevalences for each outcome for the full age range (12–17) are plotted in Figure 1; separate plots of these same outcomes for the two age groups (ages 12–14 and ages 15–17) are provided in Figure S1 (available online). Prevalence estimates for marijuana use have been described individually in annual NSDUH reports (e.g., 17). Therefore, we only describe the overall trend here. The prevalence of past-year marijuana use among adolescents declined steadily from 15.8% in 2002 to 12.5% in 2007, when it began climbing until peaking at 14.2–14.3% in 2010 and 2011. After that, a modest decline to 13.2% in 2013 was observed. Although non-linearity was apparent, we modeled past-year marijuana use as a linear function of year to evaluate the net change for the 2002–2013 period.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of past-year marijuana use (A), past-year marijuana use disorders (B), and past-year marijuana use disorders among past-year users (C), 2002–2013. Note: Lines represent fits to linear trend models and are not intended to model the functional form of the trend line. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

The trend estimate was consistent with an overall decline in past-year prevalence of use (OR=0.989 per year; 95% CI: 0.984, 0.994; p<.001), corresponding to an annual decrease in prevalence of 0.9% or an overall decline of 9.8%. The net decrease was significant for both age groups, and there was no significant difference in trend between the two groups (Ages 12–14: OR= 0.978 per year; 95% CI: 0.966 , 0.989; Ages 15–17: OR=0.987 per year; 95% CI: 0.982, 0.995; Interaction p=.12). The trend in past-year prevalence of marijuana use disorders is plotted in Figure 1B; parameters describing the trend line overall and by demographic group are listed in the top half of Table 1. Again, we modeled this outcome as a linear function of year, even though nonlinearity was apparent, in order to estimate the net change over the period. The prevalence of marijuana use disorders among adolescents declined significantly (p<.001); the odds ratio corresponds to a 2.8% reduction in relative risk per year or an overall reduction of 24%. The trend did not differ significantly by sex or age group but was not significant for Blacks (p=.27) or Hispanics (p=.96).

Table 1.

Time Trends in Past-Year Marijuana Use Disorders Among the Full Population (Top) and Among Past-Year Marijuana Users (Bottom)

| Sample | β for year (95% CI) | p | Modeled Prevalence (%),2002 (95% CI) | Modeled Prevalence (%),2013 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Full Population (N=216,852)

| ||||

| Full sample | 0.976 (0.968, 0.984) | <.001 | 4.0 (3.9, 4.0) | 3.1 (3.0, 3.1) |

| Full sample – partially adjusteda | 0.972 (0.965, 0.981) | <.001 | N/A | N/A |

| By age | ||||

| 12–14 years | 0.974 (0.950,0.998) | .033 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) |

| 15–17 years | 0.972 (0.962, 0.982) | <.001 | 6.7 (6.7, 6.8) | 5.0 (4.9, 5.1) |

| By race | ||||

| White | 0.967 (0.956, 0.976) | <.001 | 4.4 (4.3, 4.5) | 3.1 (3.0, 3.1) |

| Black | 1.004 (0.979, 1.028) | .760 | 2.8 (2.6, 2.9) | 2.9 (2.7, 3.0) |

| Hispanic | 0.996 (0.974, 1.018) | .729 | 3.8 (3.6, 3.9) | 3.8 (3.6, 3.9) |

| Other | 0.963 (0.927, 0.999) | .044 | 3.5 (3.2, 3.7) | 2.3 (2.1, 2.6) |

| By sex | ||||

| Males | 0.975 (0.964, 0.987) | <.001 | 4.4 (4.3, 4.5) | 3.4 (3.3, 3.5) |

| Females | 0.977 (0.966, 0.988) | <.001 | 3.5 (3.5, 3.6) | 2.8 (2.7, 2.8) |

|

| ||||

|

Past-Year Users (n=31,616)

| ||||

| Full sample | 0.982 (0.973, 0.991) | <.001 | 27.1 (27.1, 27.2) | 23.4 (23.3, 23.4) |

| Full sample – partially adjusteda | 0.980 (0.970, 0.989) | <.001 | N/A | N/A |

| By age | ||||

| 12–14 years | 0.995 (0.969, 1.020) | .683 | 23.4 (23.2, 23.6) | 22.4 (22.2, 22.5) |

| 15–17 years | 0.979 (0.969, 0.989) | <.001 | 27.9 (27.9, 28.0) | 23.5 (23.5, 23.6) |

| By race | ||||

| White | 0.983 (0.971, 0.994) | .003 | 26.9 (26.8, 26.9) | 23.4 (23.3, 23.4) |

| Black | 0.986 (0.959, 1.015) | .354 | 23.4 (23.2, 23.6) | 20.9 (20.7, 21.0) |

| Hispanic | 0.982 (0.959, 1.006) | .133 | 29.6 (29.5, 29.8) | 25.7 (25.5, 25.8) |

| Other | 0.948 (0.908, 0.990) | .016 | 32.4 (32.2, 32.7) | 21.1 (20.9, 21.4) |

| By sex | ||||

| Males | 0.974 (0.961, 0.987) | <.001 | 29.4 (29.3, 29.5) | 23.8 (23.7, 23.9) |

| Females | 0.991 (0.979, 1.003) | .150 | 24.6 (24.6, 24.7) | 22.9 (22.8, 23.0) |

Note: N/A = not applicable.

Trend adjusted for demographics (age, sex, race).

Figure 1C illustrates trends in the prevalence of past-year marijuana use disorders among past-year marijuana users. Parameters describing trend lines for these data are shown in the lower half of Table 1; results by demographic category are also tabulated. The trend lines indicate that the past-year conditional prevalence of marijuana use disorders underwent a significant decline between 2002 and 2013 (p < .001), corresponding to an overall relative reduction of 14%. These trends were stronger among males than females. Significant differences in trends by age were not observed, though the point estimate was not significant for the 12–14- year-old group. Likewise, significant differences in trends were not observed by race/ethnicity, though trend estimates were not significant for Blacks (p=.76) or Hispanics (p=.47).

The NSDUH contains an assessment of multiple risk and protective factors for adolescent drug use and drug problems, so post hoc analyses were conducted to identify variables that might explain the trend toward lower prevalence of marijuana use disorder. Specifically, we looked for risk factors for which mean scores may have decreased over time, or protective factors for which mean scores may have increased over time. Analyses of trends in these scores are summarized in Table 2. Yearly data for each construct are plotted in Figure S2 (available online), and analyses describing the association between each construct and marijuana use disorders are summarized in Table S3 (available online). Significant negative trends were observed for the three risk factors, and significant positive trends were observed for four of the six protective factors. Thus, seven of the nine risk/protective factors changed over time in a manner that might partially explain the downward trend in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders. The two protective factors for which scores decreased over time were drug education and religious commitment.

Table 2.

Time Trends in Nine Risk and Protective Factors: Average Annual Change in Each Construct as Estimated by Linear Trend Analysis

| Time Trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Variables | Beta | (95% CI) | p |

| Risk Factors | |||

| Arguing with parents | −0.53 | (−0.36, −0.71) | <.001 |

| Conduct problems | −1.28 | (−1.04, −1.51) | <.001 |

| Parental drug attitudes | −0.41 | (−0.20, −0.63) | <.001 |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Attitudes toward school | 0.91 | (1.45, 0.95) | <.001 |

| Activity participation | 1.20 | (1.01, 0.60) | <.001 |

| Parental monitoring | 0.60 | (0.84, 0.36) | <.001 |

| Parental affirmation | 0.49 | (0.71, 0.27) | <.001 |

| Drug education | −1.50 | (−1.25, −1.75) | <.001 |

| Religious commitment | −0.56 | (−0.31, −0.81) | <.001 |

Note: Variables were standardized to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 100; e.g., a time trend slope of 1 means a change of 0.01 standard deviation per year, on average.

Having identified seven potential explanatory factors, we examined a series of models for the trend in marijuana use disorders in which the trend estimate was adjusted for demographic variables and for one of the candidate factors. In other words, we estimated seven different models, each one adjusting for a different risk/protective factor, resulting in seven different adjusted odds ratios describing the trend. Summary results for these models are presented in Table S4 (available online). The model adjusting for the conduct problems score yielded a non-significant adjusted trend odds ratio (aOR=0.999; 95% CI: 0.990, 1.009; p=.87), whereas the trend odds ratios from models adjusting for the other factors differed minimally from the initial estimate. Full results for the trend model before and after adjustment for conduct problems are presented in Table 3. Using bootstrap resampling procedures, we verified that the difference in the magnitude of the trend before and after adjustment for conduct problems was significant at p ≤ .001. Results for the same models estimated separately for the two age groups are presented in Table S5 (available online), and show that the addition of the conduct problems to the model results in similar attenuation effects for both age groups. An additional analysis of the influence of conduct problems on the trend in marijuana use disorders that does not assume linearity of trends is shown in the Supplement 1 (Figure S3 and accompanying text, available online). Briefly, the prevalence of marijuana use disorders, adjusted for conduct problems, was calculated separately for each year of data. Those estimates were plotted by year and compared with the unadjusted prevalence estimates. The figure shows a relatively flat trend for the adjusted estimates, compared to the unadjusted estimates.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models for Trend in the Past-Year Prevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders, Before and After Adjustment for Conduct Problems

| Partially Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Year | 0.973 | (0.964, 0.981) | <.001 | 0.999a | (0.990, 1.009) | .87 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Females | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Males | 1.250 | (1.175, 1.330) | <.001 | 0.921 | (0.863, 0.982) | .01 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Black | 0.757 | (0.687, 0.835) | <.001 | 0.536 | (0.488, 0.590) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.040 | (0.958, 1.130) | .35 | 0.874 | (0.799, 0.956) | .003 |

| Other | 0.775 | (0.675, 0.889) | <.001 | 0.777 | (0.674, 0.895) | <.001 |

| Age | ||||||

| 12–14 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 15–17 | 5.618 | (5.224, 6.041) | <.001 | 5.634 | (5.241, 6.057) | <.001 |

| Conduct scoreb | --- | 1.945 | (1.907, 1.984) | <.001 | ||

Note: OR = odds ratio.

Fully adjusted OR differs from partially adjusted OR with p≤.001 as determined using bootstrap resampling. See Method for further details.

Conduct problems were operationalized using the score derived from item response theory (IRT) analyses as described in Supplement 1, available online. The IRT score was transformed to a scale ranging from zero to 6, which closely approximated a raw count of number of conduct problems endorsed (R=0.95). Thus, the odds ratio approximates the increment in marijuana use disorder risk associated with an increase of one conduct problem.

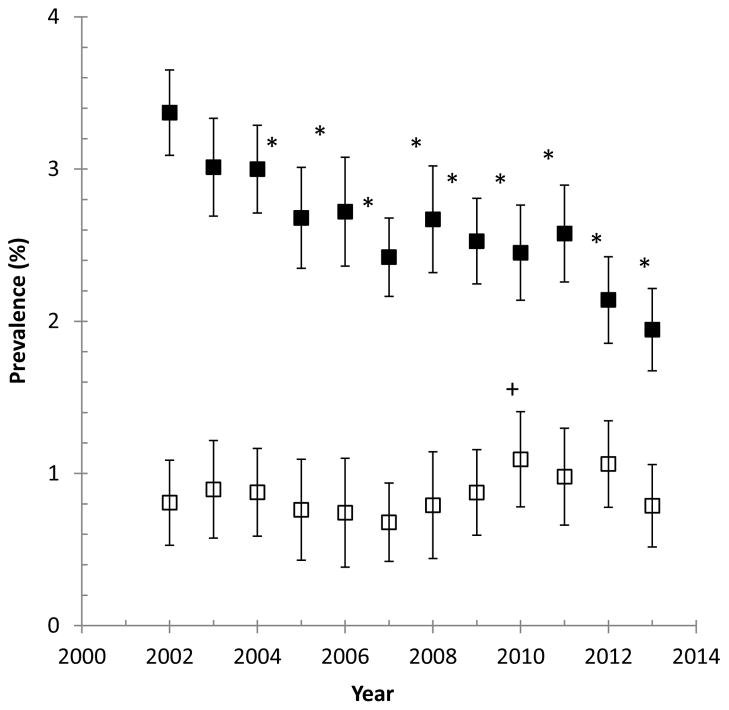

The implication of the above analyses is that the reduction in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders is specific to adolescents with conduct problems. The results suggest that there has been little or no change in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders among adolescents without conduct problems, but that there has been a decline in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders with comorbid conduct problems. This is illustrated in Figure 2, which plots the proportion of adolescents who meet criteria for marijuana use disorder but report no conduct problems, and the proportion of those who meet marijuana use disorder criteria and report one or more conduct problems. The latter values decline significantly over time, whereas there is little variation in the former series; estimates for all years except for one fell within the confidence intervals for the 2002 estimate. This analysis was conducted separately for the two age groups; results are shown in Figure S4 (available online). Despite wider confidence intervals, results for both age groups were similar to those from the unstratified analysis.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of past-year marijuana use disorders with comorbid conduct problems (filled symbols, n=71,837) and with no comorbid conduct problems (open symbols, n=144,676). Asterisks indicate (*) that the annual estimate is lower than the 2002 estimate at p<.05. Plus symbol (+) indicates that the estimate is significantly higher than the 2002 estimate at p<.05.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that, during the 2002–2013 period, the past-year prevalence of marijuana use disorders among adolescents declined by an estimated 24%, and that this decline was due to both a 10% net decline in the past-year prevalence of marijuana use and a 14% reduction in the past-year prevalence of marijuana use disorders among past-year users. We examined a number of risk and protective factors that might account for these trends, and found that the trend could be statistically explained by a decline in the prevalence of conduct problems. More specifically, we observed that the prevalence of marijuana use disorders with comorbid conduct problems declined substantially, while the prevalence of marijuana use disorders with no conduct problems remained relatively constant.

The overall decline in marijuana use is consistent with trends observed in other monitoring surveys of US youth. For example, past-year estimates of marijuana use from Monitoring the Future (MTF) 8th and 10th grade samples were about 10% lower in 2013 than in 2002.6 In contrast, the past-year prevalence of use among 12th graders exhibited no net decline in the MTF survey. The NSDUH adolescent sample does not include 18-year-olds, and this may be why we observed significant declines in use among both the younger and older age strata of the NSDUH sample (12–14-year-old and 15–17-year-old, respectively). It should also be noted that the declines in the past-year prevalence of marijuana use among adolescents that occurred during the 2002–2013 period are somewhat modest compared to those that occurred during the 1980s.6 Nonetheless, the magnitude of the decline in the prevalence of marijuana use disorders is encouraging.

Readers may be surprised at the relatively high prevalence of marijuana use disorders, which, despite a significant decline, ranged from approximately 5 to 7% among 15–17-year-olds and 1 to 1.5% among 12–14-year-olds (Figure S1B, available online). In fact, these numbers may underestimate the true prevalence, as the structured interview utilized by the NSDUH consists of fewer items and may be less sensitive than diagnostic interviews utilized in other national surveys.18–20 On the other hand, household-based diagnostic interviews may capture some relatively mild cases of substance use disorder that remit with age and without treatment.21–23 Perhaps the best way to evaluate how commonplace marijuana use disorders are among adolescents is to compare their prevalence estimates to those for alcohol use disorders and disorders related to other illicit drugs. To this end, we note that the past-year prevalence of marijuana use disorders for the entire time period was 3.5%, nearly twice as high as for disorders related to all other illicit drugs combined (1.8%), but still somewhat lower than that for alcohol use disorder (4.9%; analyses available on upon request).

The reduction in the past-year prevalence of marijuana use disorders among adolescents took place during a period when ten US states relaxed criminal sanctions against adult marijuana use, and thirteen states enacted medical marijuana policies.24,25 During this period, teenagers also became less likely to perceive marijuana use as risky, and marijuana use became more socially acceptable among young adults.6,26 Furthermore, the THC content of marijuana increased markedly over this period,27 a factor that other investigators have argued may be important in determining the dependence liability of marijuana.28 We cannot rule out the possibility that any of these factors may play a causal role in marijuana use disorders; perhaps the trend toward lower prevalence might have been stronger in the absence of these changes. However, we do find that the reduction in prevalence of marijuana use disorders may be strongly related to another major social change that occurred during this period, namely, a reduction in reported adolescent conduct problems, such as fighting and stealing.

Specifically, we found that scores on a measure of self-reported past-year conduct problems declined substantially over the 2002–2013 period, and that this phenomenon statistically accounted for the trend toward lower risk for marijuana use disorders. Put another way, we observed a decline in the proportion of adolescents who both reported conduct problems and met criteria for marijuana use disorders. In contrast, the proportion of adolescents with marijuana use disorders who did not report conduct problems remained relatively constant (Figure 2). It is increasingly recognized that childhood conduct problems and substance use disorders share common etiologies and may reflect propensity toward externalizing behaviors.29–38 Therefore, the phenomena that we observed may correspond to a more general reduction in the prevalence of externalizing behaviors. If this is the case, then declines in both conduct problems and risk for marijuana use disorders may share a common etiology, possibly related to changes in environmental factors that exert their influence earlier in childhood.30,31

While the causal pathway associating trends in conduct problems and marijuana use disorders is unclear, our findings raise an intriguing question: What factors have contributed to the recent, and possibly ongoing, reduction in conduct problems? Reductions in juvenile crime rates have been ongoing since the mid-1990s.39 Other investigators have documented secular trends toward lower rates of bullying, fighting, and theft in recent years.40–43 It seems likely that the trends documented here are related to these other social trends, and identification of environmental factors contributing to them could lead to further improvements in adolescent mental health and substance use outcomes. Some possible contributing causes mentioned in existing literature include reduced lead exposure,44 more frequent diagnosis and treatment of childhood behavior disorders,39 a rise in school-based programs to prevent violence and bullying,41 and the emergence of state anti-bullying laws.45

Our results should be interpreted in light of the known limitations of observational epidemiological research. While the study of repeated cross-sections of the population is ideal for documenting secular trends, it is a less powerful design for causal inference than individual-level longitudinal studies. Relying on self-reported data for illegal and socially proscribed behaviors always carries risk of reporting bias, though this concern is mitigated by the attention to privacy and confidentiality embedded in the NSDUH design.18,46 An additional limitation involves the diagnostic assessment used in the NSDUH. To our knowledge, this assessment has been subject to only one clinical validation study, and adolescent dependence diagnoses exhibited moderate concordance with clinician-administered interviews.16 Counterbalancing this limitation, the NSDUH interview was developed in conjunction with cognitive laboratory testing procedures to ensure comprehensibility of items by a broad range of participants, including adolescents.11 It is also the only repeated national survey that assesses alcohol and drug dependence diagnoses among adolescents. Thus, NSDUH data is uniquely capable of providing information about trends in marijuana use disorders because of the frequency of administration and consistency of methods.

Limitations notwithstanding, our findings underscore the importance of adolescent mental health in conferring resiliency to risk for substance use disorders.7–9 More importantly, our study suggests that there are one or more environmental factors—yet to be identified—that may be changing over time in a manner that leads to both lower risk for marijuana use disorders and for other behavioral problems. Identification of such factors would facilitate more effective prevention strategies for marijuana problems and other aspects of behavioral health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA): DA23668, DA32573, DA4041, and DA031288. The funding agency had no role in the design, conduct, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data, or the preparation, review, or approval of this paper.

Footnotes

R.A.G. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Public use National Survey on Drug Use and Health data were obtained from the Interuniversity Consortium for Social and Political Research.

Supplemental material cited in this article is available online.

Disclosure: Dr. Grucza has received grant or research support from the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). He has received honoraria for peer-review of National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants. He has held stock in Express Scripts and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Agrawal has received grant or research support NIAAA. She has consulted with the PhenX toolkit, which is funded by NIH and has received honoraria for peer review of NIH grants and other NIH-related service. Dr. Plunk has received grant or research support from the Virginia Foundation for Healthy Youth. Dr. Cavazos-Rehg has received honoraria for peer-review of NIH grants. Dr. Bierut has received grant or research support from NIAAA, and the National Cancer Institute. She is a member of the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse, the Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Multi-Institute (NIH) Advisory Council, a consultant for the Food and Drug Administration Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, and an advisory board member of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Smoking Cessation Panel. She has served on the speakers’ bureau for Imedex. She has owned stock in Twitter and Facebook. She is listed as an inventor on Issued US Patent 8,080,371,“Markers for Addiction,” covering the use of certain single nucleotide polymorphisms in determining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of addiction. Mss. Krauss and Bongu report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Richard A. Grucza, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Dr. Arpana Agrawal, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Dr. Melissa J. Krauss, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Dr. Jahnavi Bongu, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Dr. Andrew D. Plunk, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA.

Dr. Patricia A. Cavazos-Rehg, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Dr. Laura J. Bierut, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

References

- 1.Boyd CJ, Veliz PT, McCabe SE. Adolescents’ use of medical marijuana: A secondary analysis of monitoring the future data. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(2):241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miech RA, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg J, Patrick ME. Trends in use of marijuana and attitudes toward marijuana among youth before and after decriminalization: The case of California 2007–2013. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khatapoush S, Hallfors D. “Sending the Wrong Message”: Did medical marijuana legalization in California change attitudes about and use of marijuana? J Drug Issues. 2004;34:751–770. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: Higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed: 2/23/2016];Trends in the prevalence of marijuana, cocaine, and other illegal drug use, National YRBS: 1991–2011. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_drug_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- 6.Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2013: Overview of key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Substance use and abuse among children and teenagers. Am Psychol. 1989;44(2):242–248. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(1):67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shedler J, Block J. Adolescent drug use and psychological health: A longitudinal inquiry. Am Psychol. 1990;45(5):612–630. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gfroerer JC, Eyerman J, Chromy JR. Redesigning an Ongoing National Household Survey: Methodological Issues. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennet J, Gfroerer JC. Evaluating and Improving Methods Used in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.ICPSR. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Series. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/64. Published 2015.

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Methodological Resource Books. [Accessed August 24, 2015];Population Data /NSDUH. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/population-data-nsduh/reports?tab=39. Published 2015.

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, et al. Nosologic comparisons of DSM-IV and DSM-5 alcohol and drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(3):378–388. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan BK, Karg RS, Batts KR, Epstein JF, Wiesen C. A clinical validation of the national survey on drug use and health assessment of substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2008;33:782–798. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grucza RA, Abbacchi AM, Przybeck TR, Gfroerer JC. Discrepancies in estimates of prevalence and correlates of substance use and disorders between two national surveys. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2007;102(4):623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grucza RA, Agrawal A, Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Bierut LJ. Recent trends in the prevalence of marijuana use and associated disorders in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:300–1. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: The impact of transitional life events. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(2):195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2005;100:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobell LC, Cunningham JA, Sobell MB. Recovery from alcohol problems with and without treatment: Prevalence in two population surveys. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(7):966–972. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Cummings JR. The effect of medical marijuana laws on adolescent and adult use of marijuana, alcohol, and other substances. J Health Econ. 2015;42:64–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NORML. States That Have Decriminalized. http://norml.org/aboutmarijuana/item/states-that-have-decriminalized. Published 2015.

- 26.Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Todic J, Córdova D, Perron BE. Trends in the disapproval and use of marijuana among adolescents and young adults in the United States: 2002–2013. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(5):392–404. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1049493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White House and Office of National Drug Control Policy. National Drug Control Strategy: Data Supplement. Washington, D.C: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:325–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masse LC, Tremblay RE. Behavior of boys in kindergarten and the onset of substance use during adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):62. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130068014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caspi A. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1033. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(3):411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):929. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant JD, Lynskey MT, Madden PA, et al. The role of conduct disorder in the relationship between alcohol, nicotine and cannabis use disorders. Psychol Med. 2015;45:3505–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S14–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink, part I: Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink, part II: Familial risk and heritability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krueger RF, South SC. Externalizing disorders: Cluster 5 of the proposed meta-structure for DSM-V and ICD-11. Psychol Med. 2009;39(12):2061–70. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook PJ, Laub JH. After the epidemic: Recent trends in youth violence in the United States. Crime Justice. 2002;29:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 40.White N, Lauritsen JL. Violent crime against youth, 1994–2010. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau Justice Statistics, NJC; 2012. p. 240106. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finkelhor D. Trends in Bullying and Peer Victimization. Durham, NH: Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed 11/15/2015];Trends in the prevalence of behaviors that contribute to violence on school property, National YRBS: 1991–2013. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_violenceschool_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- 43.Perlus JG, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Iannotti RJ. Trends in bullying, physical fighting, and weapon carrying among 6th- through 10th-grade students from 1998 to 2010: Findings from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1100–1106. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nevin R. Understanding international crime trends: The legacy of preschool lead exposure. Environ Res. 2007;104(3):315–336. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatzenbuehler ML, Schwab-Reese L, Ranapurwala SI, Hertz MF, Ramirez MR. Associations between antibullying policies and bullying in 25 states. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):e152411. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller JW, Gfroerer JC, Brewer RD, Naimi TS, Mokdad A, Giles WH. Prevalence of adult binge drinking: A comparison of two national surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.