Abstract

Pneumococcal-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (pHUS) is a rare but severe complication of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. We report the case of a 12-year-old female with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome treated with adrenocorticotrophic hormone (H.P. Acthar® Gel), who developed pneumococcal pneumonia and subsequent pHUS. While nephrotic syndrome is a well-known risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease, this is the first reported case of pHUS in an adolescent patient with nephrotic syndrome, and reveals novel challenges in the diagnosis, treatment and potential prevention of this complication.

Keywords: Acthar, hemolytic, nephrotic, streptococcus, uremic

Background

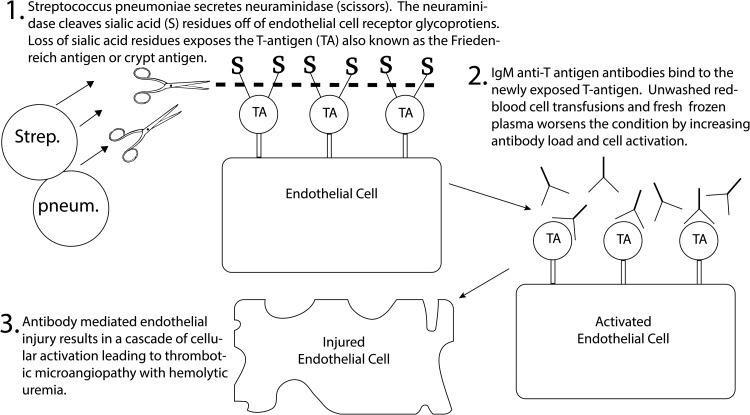

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is characterized by the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and acute renal failure. HUS in children is most commonly caused by Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), with pneumococcal-associated HUS (pHUS) accounting for 5% of acquired cases. Most cases occur in neonates and children <2 years of age. The clinical course and overall outcomes of pHUS are severe. Up to 85% of patients require dialysis with a mortality rate of >10% [1, 2]. The inciting event is endothelial damage activating a microangiopathic cascade of thrombotic vascular injury. Streptococcus pneumoniae cleaves N-acetylneuraminic acid (sialic acid) and exposes the Thomsen–Friedenreich antigen (T-antigen) on glomerular endothelial cell glycoproteins [3]. This process, known as T-activation, then leads to IgM binding from circulating IgM anti-T antibodies, and the clinical syndrome of HUS (Figure 1) [4].

Fig. 1.

A mechanism of endothelial cell injury in Streptococcal Pneumoniae associated hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Treatment of pHUS is with antibiotics with activity against S. pneumoniae and supportive care. If necessary, transfusion of washed blood products is preferable to avoid increasing the levels of preformed anti-T antibodies, which are high in unwashed products. Anecdotal evidence supports the use of plasma exchange with 5% albumin replacement, and avoiding fresh frozen plasma (FFP) due to preformed anti-T antibodies in the pooled product [5–7].

Case report

A 12-year-old female with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome presented to the emergency department with fever, shortness of breath and cough. On exam she was tachycardic and tachypneic, requiring 3 L of supplemental oxygen. She was given 1 L of normal saline bolus intravenously. A chest X-ray identified bilateral pulmonary edema. She met criteria for sepsis [8]. She was started on vancomycin and cefotaxime, and admitted to our pediatric intensive care unit for further management.

Past medical history was remarkable for the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome at the age of 5 years. Although initially responsive to steroids she suffered several relapses when the steroid dose was tapered. At the age of 6 years a renal biopsy showed findings consistent with minimal change disease. Genetic testing for inherited nephrotic syndromes identified a heterozygous, non-coding mutation in the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily C member 6 (TRPC6) gene of unknown clinical significance. She was given an 8-week course of cyclophosphamide, which induced a 1.5-year remission. After relapse and a failed attempt to induce full remission with oral steroids she was started on tacrolimus. Over the next 3 years she had a partial clinical response, with improved edema but persistent proteinuria. Out of concern for missed focal segmental glomerular sclerosis (FSGS) and long-term calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity, a repeat biopsy was performed. Biopsy showed interstitial nephritis without evidence of FSGS. Due to drug-resistant nephrotic syndrome and biopsy findings suggesting possible drug injury she was started on a trial of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (H.P. Acthar® Gel; Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, St Louis, MO, USA) twice weekly in addition to tacrolimus. She received Acthar® for 2 months prior to presentation.

In the intensive care unit

An initial blood culture grew out S. pneumoniae at 8 h, and a nasopharyngeal swab PCR was positive for parainfluenza type 2. Overnight the patient developed oliguria, the creatinine increased from 1.4 to 2.4 mg/dL, and the hemoglobin decreased from 11.4 to 7.4 g/dL (Table 1). Acthar® and tacrolimus were discontinued. She was transfused one unit of unwashed packed red blood cells (pRBCs) and started on continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration due to worsening kidney function and pulmonary edema.

Table 1.

Pertinent laboratory data

| Laboratory test | Admission (Day 1) | After PLEX (Day 8) | Day 25 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.4 | 8.6 | 10.1 | 12.1–15.1 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 22.6 | 26.4 | 29.5 | 36.1–44.3 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 100 | 81 | 225 | 140–440 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 294 | NA | NA | 100–250 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 0.9 | NA | 0–0.4 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 30 | 10 | 50 | 9.0–18.0 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.4 | 1.9 | 8 | 0.2–0.8 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 737 | 426 | NA | 177–401 |

| PT/aPTT (in seconds) | 19.4/48.6 | 21.1/43.9 | NA | 12–16.1/23–40.6 |

| DCT | NA | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| ADAMST13 | 72% | ≥70% | ||

| Smear (Schistocytes) | Positive | Negative | ||

ADAMST13, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13; DCT, direct Coombs test; NA, not available/not obtained; PLEX, plasma exchange; PT/aPTT, prothrombin time/activated partial thromboplastin time.

On hospital day 4 she developed respiratory failure requiring intubation. A computed tomography scan of the chest demonstrated bilateral patchy consolidation consistent with bronchopneumonia, and bilateral pleural effusions. High-dose hydrocortisone was administered due to concern for adrenal suppression from chronic steroid/Acthar® administration. The platelet count continued to decrease and her clinical condition worsened, requiring intravenous vasoactive support. A 5-day course of plasma exchange (PLEX) was started. Initially the presumed mechanism for her worsening clinical course was the development of thrombocytopenia-associated multiple organ failure; therefore, FFP was used as the replacement fluid during the exchange [9]. The possibility of pHUS was raised shortly after initiation of PLEX and the lack of clinical response to replacement with FFP. A direct Coombs test was checked and came back negative; however, a false negative could be explained by the removal of plasma antibodies from PLEX [10]. Indeed, a follow-up direct Coombs test drawn after completion of PLEX was positive.

The platelet count reached a nadir of 36 on Day 13, after which it slowly improved without the need for transfusion. With supportive care, antibiotics and temporary kidney replacement therapy (KRT), the patient slowly recovered. She was eventually discharged home on hospital day 39, her creatinine having returned to the baseline level of 0.6 mg/dL. She is currently on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy with persistent nephrotic syndrome.

Discussion

Diagnosis of pHUS is based on the association of the clinical triad of HUS with confirmed or suspected S. pneumoniae infection [11]. Evidence of T-antigen exposure (direct Coombs test, polyagglutination test or peanut lectin agglutination test) can help support the diagnosis, but is not mandatory [12]. The patient met diagnostic criteria for pHUS, and additionally had a positive direct Coombs test (Table 1). While disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with multiorgan failure was considered as an alternative diagnosis, it was eventually rejected due to evidence of autoimmune hemolysis (schistocytes, positive Coombs), and normal fibrinogen level. Initially the mildly prolonged prothrombin time/activated partial thromboplastin time (PT/aPTT) hinted toward the possibility of DIC, but coagulation abnormalities are common in pHUS, and DIC is typically not considered without significant PT/aPTT elongation along with decreased fibrinogen.

One unique aspect of this case was the patient's age and risk factors. The median age of pHUS reported in the literature ranges from 13 to 24 months [1, 13, 14]. Four cases of pHUS in adults have been reported [15–18]. Two of these patients had undergone splenectomy, and so underlying immunodeficiency is presumably a risk factor for development of pHUS at an older age. Nephrotic syndrome is a well-known cause of secondary immunodeficiency due to multiple factors including edema, urinary loss of immunoglobulins and complement factors, and secondary effects of cytotoxic therapies [19–21]. Streptococcus pneumoniae in particular is a major cause of sepsis and peritonitis in nephrotic syndrome [22], yet this is the first reported case of pHUS in a patient with nephrotic syndrome.

Another potential risk factor in this patient was her exposure to immunosuppressive agents. Tacrolimus has a well-known association with HUS, but does not typically cause a positive Coombs test. Also, in a review of 16 cases of tacrolimus-induced HUS, the average time from initiating tacrolimus to disease onset was 7.1 months, while our patient had been treated for over 3 years [23]. In addition to tacrolimus, our patient was started on Acthar® 2 months prior to presentation. H.P Acthar® Gel is a repository corticotropin injection that was first approved by the FDA in 1952 for a variety of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and is an approved treatment for nephrotic syndrome [24]. Proposed mechanisms of action include increased endogenous steroidogenesis, immunomodulation via melanocortin receptor binding and podocyte protection [25]. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) therapy is tolerated by most patients, with adverse effects similar to those of glucocorticoid therapy (weight gain, bone loss, Cushingoid features). Although we do not suspect a pathogenic role of ACTH in the development of HUS, and our patient had several risk factors for pneumococcal infection, it is worth noting this serious complication in the setting of Acthar® administration.

The clinical course of pHUS is typically more severe than diarrheal HUS, with more frequent need for dialysis and transfusions, and longer hospital stays [26]. In 2008, Copelovitch and Kaplan reviewed all previous cases of pHUS reported in the English literature, and found a 12.3% mortality rate, with 10% progressing to end-stage renal disease, and 16% with chronic kidney disease and/or hypertension [2]. Management of pHUS is primarily supportive, with prompt administration of antibiotics, transfusions and KRT as needed. FFP and unwashed pRBCs should be avoided, due to the possibility of increased exposure to anti-T antigen IgM antibodies.

Plasma exchange with 5% albumin replacement fluid has been advocated for the treatment of pHUS due to the theoretical benefit of removing anti-T IgM antibodies and bacterial neuraminidase. Guidelines rate the indication for plasma exchange as a category III: optimum role of apheresis therapy is not established and care should be individualized [27]. Further conclusions cannot be reached without a randomized controlled trial or high-powered case series.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that children aged 6–18 years with immunocompromising conditions (including nephrotic syndrome) receive both the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) (Table 2) [28]. The epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease, and pHUS in particular, has been altered dramatically with the introduction of pneumococcal vaccines. Most notably, rates of invasive pneumococcal disease have plummeted in children younger than 5 years, and non-vaccine serotypes have risen in prevalence [29]. The patient received PCV7 vaccination from her primary pediatrician, but did not receive subsequent PCV13 or PPSV23. Results of serotyping for this case are still pending, but the possibility that the infection was caused by a vaccine-preventable serotype underscores the importance of ensuring vaccine understanding among both community and specialist pediatricians.

Table 2.

Pneumococcal immunization recommendations in nephrotic syndrome

| ACIP recommendations for PCV13 and PPSV23 administration in children aged 6–18 years old with immunocompromising conditions (including nephrotic syndrome) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PCV13 | PPSV23 | PPSV23 | |

| Patients who have NOT previously received PPSV23 | 1 dose | 1st dose ≥8 weeks after PCV13 dose | 2nd dose ≥5 years after 1st PPSV23 dose |

| Patients who have previously received PPSV23 | 1 dose ≥8 weeks after last PPSV23 dose | N/A—already received 1st dose | ≥5 years after 1st PPSV23 dose |

ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PPSV23, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges that pHUS presents, and the importance of early recognition. Management often requires intensive supportive care with dialysis, transfusion with washed blood products and consideration of PLEX with 5% albumin. This case also highlights the need to consider pHUS in older patients with immunocompromising conditions such as nephrotic syndrome that increase the risk of invasive pneumococcal infection. Finally, proper vaccination practices are important to help prevent pneumococcal disease and its associated sequelae.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Banerjee R, Hersh AL, Newland J et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome among children in North America. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30: 736–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copelovitch L, Kaplan BS. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2008; 23: 1951–1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein PJ, Bulla M, Newman RA et al. Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen in haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. Lancet 1977; 2: 1024–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cochran JB, Panzarino VM, Maes LY et al. Pneumococcus-induced T-antigen activation in hemolytic uremic syndrome and anemia. Pediatr Nephrol 2004; 19: 317–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGraw ME, Lendon M, Stevens RF et al. Haemolytic uraemic syndrome and the Thomsen Friedenreich antigen. Pediatr Nephrol 1989; 3: 135–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopkins CK, Yuan S, Lu Q et al. A severe case of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with pneumococcal infection and T activation treated successfully with plasma exchange. Transfusion 2008; 48: 2448–2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petras ML, Dunbar NM, Filiano JJ et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange in Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: a case report. J Clin Apher 2012; 27: 212–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 165–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen TC, Han YY, Kiss JE et al. Intensive plasma exchange increases a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin motifs-13 activity and reverses organ dysfunction in children with thrombocytopenia-associated multiple organ failure. Crit Care Med 2008; 36: 2878–2887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winters JL. Plasma exchange: concepts, mechanisms, and an overview of the American Society for Apheresis guidelines. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012; 2012: 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariceta G, Besbas N, Johnson S et al. Guideline for the investigation and initial therapy of diarrhea-negative hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2009; 24: 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loupiac A, Elayan A, Cailliez M et al. Diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32: 1045–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bender JM, Ampofo K, Byington CL et al. Epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome in Utah children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29: 712–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waters AM, Kerecuk L, Luk D et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with invasive pneumococcal disease: the United Kingdom experience. J Pediatr 2007; 151: 140–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers KA, Marrie TJ. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17: 1037–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Eyben FE, Szpirt W. Pneumococcal sepsis with hemolytic-uremic syndrome in the adult. Nephron 1985; 40: 501–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohlmann D, Hamann GF, Hassler M et al. Involvement of the central nervous system in hemolytic uremic syndrome/thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nervenarzt 1996; 67: 880–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds E, Espinoza M, Monckeberg G et al. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Rev Med Chil 2002; 130: 677–680 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron JS. The nephrotic syndrome and its complications. Am J Kidney Dis 1987; 10: 157–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson DC, York TL, Rose G et al. Assessment of serum factor B, serum opsonins, granulocyte chemotaxis, and infection in nephrotic syndrome of children. J Infect Dis 1979; 140: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McVicar MI, Chandra M, Margouleff D et al. Splenic hypofunction in the nephrotic syndrome of childhood. Am J Kidney Dis 1986; 7: 395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uncu N, Bulbul M, Yildiz N et al. Primary peritonitis in children with nephrotic syndrome: results of a 5-year multicenter study. Eur J Pediatr 2010; 169: 73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin CC1, King KL, Chao YW et al. Tacrolimus-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: a case analysis. J Nephrol 2003; 16: 580–585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bomback AS, Canetta PA, Beck LH Jr et al. Treatment of resistant glomerular diseases with adrenocorticotropic hormone gel: a prospective trial. Am J Nephrol 2012; 36: 58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong R. The renaissance of corticotropin therapy in proteinuric nephropathies. Nat Rev Nephrol 2012; 8: 122–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt J, Wong C, Mihm S et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease and hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatrics 2002; 110 (2 Pt 1): 371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz J, Winters JL, Padmanabhan A et al. Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical practice-evidence-based approach from the Writing Committee of the American Society for Apheresis: the sixth special issue. J Clin Apher 2013; 28: 145–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett NM, Pilishvili T, Whitney CG et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among children aged 6–18 years with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62: 521–524 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steenhoff AP, Shah SS, Ratner AJ et al. Emergence of vaccine-related pneumococcal serotypes as a cause of bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42: 907–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]