Abstract

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis has been observed in <1% of native renal biopsies. Here, we describe two patients with granulomatous interstitial nephritis in relation to Crohn's disease. Circulating helper and cytotoxic T cells were highly activated, and both cell types predominated in the interstitial infiltrate, indicating a cellular autoimmune response. After immunosuppressive treatment, renal function either improved or stabilized in both patients. In conclusion, granulomatous interstitial nephritis is a genuine extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn's disease, the treatment of which should include immunosuppressive agents.

Keywords: calcineurin inhibitors, Crohn's disease, granulomatous interstitial nephritis, inflammatory bowel disease, T cells

Background

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, probably reflect systemic inflammation, autoimmune susceptibility and/or drug-related toxicities [1]. Although these manifestations are prevalent, parenchymal renal disease as such is considered rare. However, renal biopsies from patients with IBD can reveal a wide spectrum of pathologies most commonly affecting the glomerular and tubulo-interstitial compartments [2].

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis in the absence of glomerulonephritis or vasculitis has been associated with various aetiologies, particularly with drug hypersensitivities, infections and miscellaneous causes such as sarcoidosis, while others are classified as idiopathic to conceal our ignorance about causes [3–5]. Ambruzs et al. [2] found granulomatous interstitial nephritis in ∼5% of renal biopsies from patients with IBD, the occurrence of which was linked to current or recent past exposure to 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) preparations. Because of their study design, a causal relationship cannot be concluded, however. Here, we report two patients with granulomatous interstitial nephritis in relation to Crohn's disease, which was not associated with 5-ASA. On the basis of our clinicopathologic observations, a pathophysiological mechanism has been proposed.

Case reports

Case 1

A 19-year-old man who had been well until 4 months previously presented with abdominal discomfort and changing bowel habits. Although his appetite was normal, he had lost 6 kg of weight. The review of systems was entirely negative. There was no history of ingestion of any drugs. On physical examination, no abnormalities were found. Laboratory tests showed mild normochromic normocytic anaemia and an increased CRP of 38 mg/L. The white blood cell count revealed no abnormalities. Serum creatinine was 177 µmol/L [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), 43 mL/min/1.73 m2], and isolated aseptic leukocyturia was present. A renal biopsy was obtained and revealed granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Chest X-ray and an interferon gamma release assay for tuberculosis were unremarkable. Also, endoscopic biopsies of the terminal ileum and colon were obtained because of the abdominal complaints and an increased faecal calprotectin of 1136 μg/g (reference range, <150 μg/g), after which a diagnosis of Crohn's disease was made. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis was therefore considered an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn's disease. The patient had been treated with three pulses of methylprednisolone, followed by oral prednisolone 50 mg/day (tapered to 5 mg/day over a 3-month period) and tacrolimus (target level of 5–7 μg/L). Currently, the patient is doing well with no signs of active disease. Renal function improved (serum creatinine, 133 µmol/L; eGFR, 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), while Crohn's disease remitted.

Case 2

Subsequently, a 22-year-old woman with a history of biopsy-proven Crohn's disease had been treated with mesalamine, mercaptopurine and adalimumab. All drugs were stopped because of remitting disease, after which serum creatinine increased from 101 to 160 µmol/L (eGFR, 37 mL/min/1.73 m2) and isolated aseptic leukocyturia developed. A renal biopsy revealed tubulo-interstitial nephritis without granulomata. Despite high-dose corticosteroids and monthly pulses of 500 mg cyclophosphamide for 6 months, serum creatinine increased to 233 µmol/L (eGFR, 23 mL/min/1.73 m2). Therefore, the patient was referred to our hospital.

At the time of presentation, abdominal discomfort was not present and her defecation was normal. Fatigue was reported, however. On physical examination, no abnormalities were found. Laboratory tests showed mild normochromic normocytic anaemia and an increased CRP of 114 mg/L. The white blood cell count revealed no abnormalities. Aseptic leukocyturia had persisted. Because of refractory disease, another renal biopsy was obtained, which revealed granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography scanning of the whole body was unremarkable, as was the further workup for drug hypersensitivities, infections and common variable immunodeficiency. Thus, granulomatous interstitial nephritis as an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn's disease was diagnosed. The patient was treated with three pulses of methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisolone 50 mg/day (tapered over a 3-month period), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 2000 mg/day and ciclosporine 200 mg/day. Although her renal function and inflammatory markers initially improved, chronic kidney disease stage 4 (eGFR, 28 mL/min/1.73 m2) developed.

Clinicopathologic findings

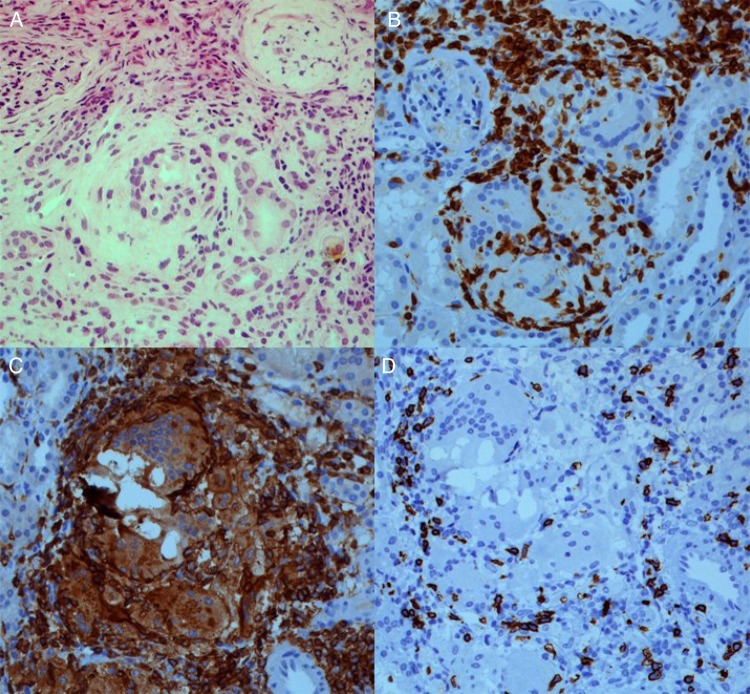

Light microscopy of the renal biopsies revealed a predominant lymphocytic cell infiltrate, occasional eosinophils and the formation of noncaseating granulomata in the tubulo-interstitial compartment (Figure 1A), whereas glomerular and vascular lesions were not found. Fungi, acid fast bacilli, crystals and polarized material were not observed. Routine immunofluorescence was negative.

Fig. 1.

Renal biopsy revealing granulomatous interstitial nephritis (A; haematoxylin and eosin, 200×). Immunohistochemistry staining revealing a predominant T cell infiltrate (B; CD3, 200×), consisting of both T-helper cells (C; CD4, 200×) and cytotoxic T cells (D; CD8, 200×). Of note, neither crystals nor polarized material was observed.

In Case 2, immunohistochemistry was performed, which revealed an abundant CD3+ T cell infiltrate including both T helper (CD3+ CD4+) and cytotoxic T cells (CD3+ CD8+); histiocytes (CD3– CD4+) were also observed (Figure 1B–D). Few polytypic plasma cells (CD138+) but no B cells (CD20+) were found. The phenotype of circulating lymphocytes was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis, and although the distribution of lymphocyte subsets was normal, T-helper and cytotoxic T cells were highly activated as illustrated by an enhanced HLA-DR expression (8.4 and 20.3%, respectively). Furthermore, increased levels of the soluble interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptor (11 600 pg/mL; reference range, <3154 pg/mL) were found.

Discussion

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis is considered an uncommon pathological finding (<1% of native renal biopsies) that has been associated with various aetiologies, of which drug hypersensitivities and sarcoidosis encompass the majority of cases [4, 5]. An extensive workup was unremarkable, and, thus, granulomatous interstitial nephritis as a genuine extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn's disease was diagnosed.

Renal and lower genitourinary involvement in IBD usually manifest as urinary calculi and fistulas, which has been observed in 10–15% of patients [6]. Although parenchymal renal disease in IBD has been described [2], granulomatous interstitial nephritis as such is considered extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 12 patients (including 7 case reports; Table 1) have been described in the English literature [2, 7–13]. Remarkably, both our cases were diagnosed over the past year, suggesting that the incidence may have been underestimated. Because all patients presented with renal impairment with only subtle urinary abnormalities, it is advisable that renal function should be monitored in all patients with IBD and that a renal biopsy should be considered for those patients with a persistent increase in serum creatinine.

Table 1.

Reported cases of granulomatous interstitial nephritis in patients with IBD

| Age (years, gender) | 5-ASA | Creatinine, t0 (µmol/L) | Treatment | Creatinine, tx (µmol/L) | Follow-up (years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Archimandritis and Weetch [7] | 22, M | N | ND | colectomy | ND | 4 |

| Marcus et al. [8] | 16, F | N | 221 | CS, 6-MP, anti-TNFα | 185 | 1 |

| Unal et al. [9] | 43, M | N | 229 | CS | 185 | 0.1 |

| Polci et al. [10] | 56, M | Y | 274 | CS, anti-TNFα | ESRD | 1 |

| Colvin et al. [11] | 23, M | Y | 203 | CSa | 97 | 1.8 |

| Saha et al. [12] | 17, M | N | 397 | CS, AZA, anti-TNFα | 813 | 1.5 |

| Timmermans et al. | 19, M | N | 177 | CS, CsA | 133 | 1 |

| 22, F | N | 233 | CS, FK506, MMF | 186 | 1 | |

| Ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Alivanis et al. [13] | 19, M | Y | 618 | CSa | 79 | 1 |

6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine; AZA, azathioprine; CS, corticosteroids; CsA, ciclosporine; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; FK506, tacrolimus; ND, not determined.

aCessation of 5-ASA after the diagnosis of granulomatous interstitial nephritis.

The pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Although drug-induced nephrotoxicity by 5-ASA has been considered an aetiological factor in tubulo-interstitial nephritis [2, 14], there is no clear relationship between the duration and dose and the development of renal disease. However, our first case describes the concurrent presentation of granulomatous interstitial nephritis and Crohn's disease in a treatment-naïve patient, whereas there was no recent past exposure to 5-ASA in our second case. Furthermore, half the reported cases were not linked to 5-ASA (Table 1) [7–9, 12], suggesting another pathophysiological mechanism.

The predominance of T-helper and cytotoxic T cells in the renal interstitium combined with the highly activated nature of these T cells in the peripheral circulation suggest a cellular (auto)immune response directed against an antigen in the renal interstitium. Therefore, we postulate that during an active episode of Crohn's disease these T cells have been primed and activated against gastrointestinal antigens and simultaneously against components of the renal interstitium, presumably due to antigenic cross-reactivity. These reactive T cells induce the differentiation of effector T cells, such as cytotoxic T cells, mediating cytotoxicity. Of note, serum levels of the soluble IL-2 receptor, a marker of T-cell activation, paralleled disease activity (data not shown), indicating that the soluble IL-2 receptor may be a useful biomarker of the disease.

There is no standard of care for the management of granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Joss et al. observed that corticosteroid treatment was effective in most patients with granulomatous interstitial nephritis regardless of the underlying cause [4]. However, the treatment of patients with granulomatous interstitial nephritis as an extraintestinal manifestation of IBD can be challenging (Table 1). Calcineurin inhibitors were therefore started. Furthermore, MMF was added in the second case because of its efficacy in refractory interstitial nephritis [15]. During follow-up, renal function improved or stabilized in both patients, suggesting that a more aggressive immunosuppressive regimen may be beneficial in the treatment of such patients.

In conclusion, granulomatous interstitial nephritis is a genuine extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn's disease, which is presumably due to systemic immune dysregulation and T-cell activation. Monitoring of renal function is therefore advisable regardless of 5-ASA treatment for patients with IBD. Furthermore, the use of additional immunosuppressive agents should be considered in addition to corticosteroids.

Authors’ contributions

S.A.M.E.G.T., M.H.L.C., J.G.M.C.D., and P.v.P. have made substantial contributions to the conception and study design, acquisition of data and/or the analysis and interpretation of data. S.A.M.E.G.T., M.H.L.C. and P.v.P. drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved its final version for submission.

Conflict of interest statement

The results presented in this manuscript have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

References

- 1.Danese S, Semeraro S, Papa A et al. . Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 7227–7236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambruzs JM, Walker PD, Larsen CP. The histopathologic spectrum of kidney biopsies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 9: 265–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robson MG, Banerjee D, Hopster D et al. . Seven cases of granulomatous interstitial nephritis in the absence of extrarenal sarcoid. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18: 280–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joss N, Morris S, Young B et al. . Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2: 222–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bijol V, Mendez GP, Nose V et al. . Granulomatous interstitial nephritis: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases from a single institution. Int J Surg Pathol 2006; 14: 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Serag HB, Zwas F, Bonheim NA et al. . The renal and urologic complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1997; 3: 217–224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archimandritis AJ, Weetch MS. Kidney granuloma in Crohn's disease. BMJ 1993; 307: 540–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcus SB, Brown JB, Melin-Aldana H et al. . Tubulointerstitial nephritis: an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008; 46: 338–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unal A, Sipahioglu MH, Akgun H et al. . Crohn's disease complicated by granulomatous interstitial nephritis, choroidal neovascularization, and central retinal vein occlusion. Intern Med 2008; 47: 103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polci R, Mangeri M, Faggiani R et al. . Granulomatous interstitial nephritis in a patient with Crohn's disease. Ren Fail 2012; 34: 1156–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colvin RB, Traum AZ, Taheri D et al. . Granulomatous interstitial nephritis as a manifestation of Crohn disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2014; 138: 125–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha MK, Tarek H, Sagar V et al. . Role of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in granulomatous interstitial nephritis secondary to Crohn's disease. Int Urol Nephrol 2014; 46: 229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alivanis P, Aperis G, Lambrianou F et al. . Reversal of refractory sulfasalazine-related renal failure after treatment with corticosteroids. Clin Ther 2010; 32: 1906–1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gisbert JP, Gonzalez-Lama Y, Mate J. 5-Aminosalicylates and renal function in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007; 13: 629–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Preddie DC, Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J et al. . Mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1: 718–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]