Abstract

Psychiatric education is confronted with three barriers to managing stigma associated with mental health treatment. First, there are limited evidence-based practices for stigma reduction, and interventions to deal with stigma against mental health care providers are especially lacking. Second, there is a scarcity of training models for mental health professionals on how to reduce stigma in clinical services. Third, there is a lack of conceptual models for neuroscience approaches to stigma reduction, which are a requirement for high-tier competency in the ACGME Milestones for Psychiatry. The George Washington University (GWU) psychiatry residency program has developed an eight-week course on managing stigma that is based on social psychology and social neuroscience research. The course draws upon social neuroscience research demonstrating that stigma is a normal function of normal brains resulting from evolutionary processes in human group behavior. Based on these processes, stigma can be categorized according to different threats that include peril stigma, disruption stigma, empathy fatigue, moral stigma, and courtesy stigma. Grounded in social neuroscience mechanisms, residents are taught to develop interventions to manage stigma. Case examples illustrate application to common clinical challenges: (1) helping patients anticipate and manage stigma encountered in the family, community, or workplace; (2) ameliorating internalized stigma among patients; (3) conducting effective treatment from a stigmatized position due to prejudice from medical colleagues or patients’ family members; and (4) facilitating patient treatment plans when stigma precludes engagement with mental health professionals. This curriculum addresses the need for educating trainees to manage stigma in clinical settings. Future studies are needed to evaluate changes in clinical practices and patient outcomes as a result of social neuroscience-based training on managing stigma.

Keywords: Curriculum development, Residents, Neurosciences

The Greeks, who were apparently strong on visual aids, originated the term stigma to refer to bodily sins designed to expose something unusual and bad about the moral status of the signifier. The signs were cut or burnt into the body and advertised that the bearer was a slave, a criminal, or a traitor—a blemished person, ritually polluted, to be avoided, especially in public places.

“From Stigma by Erving Goffman ([1], p. 1)”

People diagnosed with mental illnesses are too often viewed as incompetent, irresponsible, unpredictable, and dangerous [2]. Psychiatrists are often viewed negatively by the public and medical colleagues as odd, ineffectual, agents of repression, abusive, or suffering from mental illnesses [3]. A 2009 Task Force of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) found stigma against psychiatry and psychiatrists to exist in every society studied [3]. Professional psychiatric organizations repeatedly attempt campaigns against stigma as a centerpiece of health policy and advocacy. After examining 7296 publications worldwide, however, the WPA Task Force found a scarcity of research on interventions that effectively combat stigma, and no studies at all on interventions specifically targeting stigmatization and discrimination of psychiatrists [3]. Further, public campaigns and interventions to educate the public about the neurobiological bases of mental illnesses have limited benefits and may worsen stigmatization of person with mental illness [4–6]. The term “stigma” itself has come under scrutiny as too all-inclusive for a broad range of negative experiences associated with mental illness, thus limiting elucidation of specific mechanisms and effective interventions.

There are reasons for optimism, however. Recent decades of social psychology research have identified fundamental and distinct social processes that produce stereotyping, stigmatization, prejudice, and discrimination [2]. Interventions that facilitate face-to-face interactions between health workers and persons in recovery from mental illnesses have shown promise for reducing stigma [5]. Processes by which these social exposure models work is supported by social neuroscience research, which has elucidated neural circuitry of social cognition that transforms detection of a mark of stigma into specific aversive emotions and discriminatory behaviors [7]. This emerging understanding of social cognition at behavioral and neural circuitry levels has opened new avenues for defining and combating stigma against psychiatry and mental illnesses. We suggest that

Social neuroscience research can display step-wise, sequential processing of social information within brain circuitry and signaling pathways;

Stigma assessment based upon social psychology and social neuroscience can identify types of stigma with strategies best fitted for countering that type;

Social psychology research has begun empirically validating effective interventions for neutralizing stigma and prejudice. However, these evidence-based interventions have not yet been broadly disseminated within psychiatric training and clinical practices. A clinical model for stigma management based upon social psychology and social neuroscience research can help remedy this shortfall if taught during psychiatry residencies.

The George Washington University (GWU) psychiatry residency has developed a curriculum for training psychiatry residents to assess, formulate, and implement interventions to attenuate stigma. This is in keeping with the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) Milestone Project, which identifies integration of knowledge of neurobiology into advocacy for psychiatric patient care and stigma reduction (Milestone 5.4/D) as a high-tier competency [8]. The GWU curriculum is informed by social psychology and social neuroscience research [9–11]. In this paper, we present the conceptual background for understanding stigma from a social psychology and social neuroscience perspective. Then, we summarize educational modules with associated case illustrations for teaching residents.

This innovative curriculum addresses three gaps in academic psychiatry: the lack of interventions for stigma reduction in psychiatric care; the lack of training techniques on stigma reduction for trainees; and the lack of models for stigma reduction that incorporate neuroscience in accord with ACGME/ABPN Milestones [8].

Stigma—An Affliction of Normal People and Normal Brains

Stigma is “the situation of the individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance” ([1], preface) due to “the dynamics of shameful differentness” ([1], p. 140). Stigma is a social construction that involves two fundamental components: the recognition of difference based on some distinguishing characteristic—a “mark,” and a consequent devaluation of that person [1, 12]. Stigma can arise from membership in a group, such as “the mentally ill” or “psychiatrists,” who are devalued in particular social contexts [13]. Stigmatized individuals are regarded as flawed, compromised, and somehow less than fully human, identifiable by the presence of their mark. Stigma can rob a person with a mental illness of much that makes life worth living.

Goffman’s original ethnographic descriptions of how stigma processes occur have been updated through understandings from evolutionary psychology about why stigmatization occurs. Evolutionary psychology suggests that stigma is a byproduct of normal group behavior [14]. Hominid evolution was associated with increasing capacities for organizing tightly cohesive, organized groups. These capacities manifest as leadership and followership, hierarchy, roles and responsibilities, boundaries, and reciprocal altruism within groups. The capacity to detect group members who were deemed too different or who risked impeding the group’s functioning became the human capacity to stigmatize.

From an evolutionary perspective, stigma is cognitively efficient: stigma results from cognitive heuristics and biases that make reflective thought unnecessary for rapid social judgments [15]. Functional brain imaging has clarified how these evolutionary processes of social cognition derive from dual systems: one for rapid, categorical, group member-to-group member relatedness and another for slower, individualized, person-to-person relatedness. Categorical social cognition functions as a threat detection and management system that ensures security of the group. Categorical social cognition relies upon sociobiological systems that act as sensors, conducting surveillance over social space. These include sociobiological systems for social hierarchy, peer affiliation (ingroup social bonds), social exchange (in-group reciprocal altruism), and kin recognition (distinguishing in-group from out-group members) ([16], pp. 13–55). Each system appears to have distinct circuitry elements [17].

Types of stigma reflect different survival concerns for the reference group and are reflected in different methods for social surveillance. These different methods require specific counter-tactics to disrupt their operations. Stigma types particularly relevant for persons with mental illnesses include the following:

Peril stigma triggers perceptions of potential danger, such as a person with a mental illness who shows odd, impulsive, or unpredictable behaviors;

Moral stigma is stigma in which a person is perceived as a threat for challenging the group’s beliefs and values. Symptoms of mental illness, such as a patient’s negative symptoms of psychosis, behavioral avoidance of anxiety disorders, or apathy of depression, may trigger moral stigma when interpreted as laziness, unwillingness to accept personal responsibility for one’s life, or lack of predictable conformity to social rules of engagement.

Disruption stigma occurs when a person’s behaviors or symptoms are experienced as interfering with functioning of the family or work group. Interaction with persons living with physical disabilities may invoke disruption stigma because of concern that professional and social obligations will be threatened by tending to that person’s needs. Within healthcare systems, clinicians engage in disruption stigma when psychiatric patients are not given equal diagnostic vigilance or when they are “dumped” onto other services.

Empathy fatigue represents a form of stigma when family members, friends, and co-workers feel too distressed to engage in close proximity with persons in suffering, i.e., a feeling that it is “too much emotional work.” The result is avoidance or high levels of social distance. Mental illnesses associated with feelings of severe depression, anxiety, and chronic pain may evoke empathy fatigue.

Courtesy stigma is stigma by association that results in loss of social status with physical proximity to a stigmatized person, as if acquiring “courtesy membership” in the stigmatized group [1]. Family members or mental health professionals are vulnerable to courtesy stigma by virtue of association with persons with mental illness.

The most difficult of all stigmatizing processes to counter is perhaps internalized stigma. Internalized stigma results when stigma of whatever specific type becomes a lens for self-perception that is judgmental, contemptuous, and dismissive [4]. Patients feel disgust for their identity as psychiatrically ill. Compassion for self is difficult to muster. Loss of self-esteem, a sense of alienation, social withdrawal, and self-hatred are common sequelae.

During categorical social cognition, the sociobiological systems stream information about the social world through the rostral anterior cingulate gyrus where it can be compared to a model of expectable reality that has been constructed by the prefrontal cortex from memory retrieval [18]. Detecting a mark of stigma in a person’s environment appears to generate conflict between incoming sociobiological information and an expectable reality. When the anterior cingulate gyrus detects this conflict, a need for additional control is signaled to the prefrontal cortex. The dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortices then resolve the conflict by exercising top-down modulation over subcortical systems that constitute the pain matrix, including the amygdala (fear), insula (disgust), and ventral anterior cingulate gyrus (suffering) [17–19]. Activation of the pain matrix produces proximate motivation for avoiding or extruding the bearer of the stigmatizing mark. The flow of mirror neuron information is then suppressed, and person-to-person social cognition fails to activate. Empathy for the stigmatized person is suspended. The stigmatized person is then behaviorally extruded and oppressed, for which the stigmatizer typically feels no guilt ([16], pp. 36–55).

Different types of stigma can recruit different brain circuits and signaling pathways. Moral stigma, for examples, activates circuitry of ventromedial prefrontal cortex that is essential for generating social disgust [20]. Patients with damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex lose their aversion to intimate contact with strangers, social deviants, or those bearing misfortunes, such as the poor or homeless, whereas their moral disgust remained intact for those who violated the dignity of others, as with unfairness, cheating, or betrayal [20].

Designing Interventions to Counter Stigma

The goal in stigma management is to move from these categorical processes to person-to-person relatedness, which is organized out of the mirror neuron system and medial prefrontal systems for mentalization and empathy. These “slow” systems from a cognitive processing perspective permit a highly individualized appraisal of another person that includes emotional attunement ([16], pp. 1355). Decety and colleagues [21] suggest that some aspects of physician training and experience may reduce mirror neuron mediated empathy. This suggestion was based on their finding that non-medical participants showed different patterns of event-related brain potentials (ERP) when witnessing people experiencing painful vs. non-painful stimuli, whereas internal medicine physicians showed no ERP differences when watching persons experiencing painful vs. non-painful stimuli. Reciprocal inhibition between person-to-person social cognition and categorical social cognition, which would potentially reestablish some aspects of empathy, provides a major strategy for countering interpersonal stigma. When a personal relationship can be established with another individual, categorical perception of that individual predictably fades from attention. These pathways likely underlie the effectiveness of social contact/exposure anti-stigma interventions that facilitate interaction between potential stigmatizers and persons with mental illness in recovery [5]. Establishing person-to-person relatedness with a potential stigmatizer as quickly as possible is thus a high priority for a person at risk for stigmatization.

A second strategy has its underpinnings in the relationship between high arousal states and a bias towards categorical social cognition. Activation of the anterior cingulate gyrus by perception of a stigmatizing mark not only activates the prefrontal cortex but also the ventrolateral tegmentum (dopaminergic pathways) and locus coeruleus (noradrenergic pathways). These monoamine systems ascend to cortical and limbic regions where their modulation heightens brain arousal, primes the orienting reflex, and re-allocates attention for sensitized detection of marks of stigma [18]. Arousal due to threat, ambiguity, or uncertainty thus produces a shift towards categorical social cognition. Conversely, a lowering of arousal produces a shift towards person-to-person social cognition. Lowering arousal can be achieved by minimizing perception of threat, reducing ambiguity, and bolstering a sense of coherence and predictability about the potential stigmatizer’s circumstances.

Activating person-to-person social cognition, while diminishing alertness to threat, together form the bedrock for building strategies to counter stigma in interpersonal interactions that psychiatrists face in clinical practice.

GWU Residency Seminar on Social Psychology and Social Neuroscience of Stigma

Our George Washington University (GWU) psychiatry residency has created a didactic curriculum that teaches both a scientific knowledgebase for understanding stigma against mental illness and skill-sets for assessing, formulating, and intervening to attenuate stigma. This seminar teaches residents how to manage five types of clinical encounters in which psychiatrists commonly confront stigma.

The 8-week combined postgraduate year-III (PGY-III) and PGY-IV seminar integrates the study of social psychology and social neuroscience research literature with experiential exercises and clinical portfolios of assessment, formulation, and anti-stigma interventions conducted within residents’ clinical settings. A full description of this seminar with learning objectives, readings, exercises, and methods of assessment are available from the authors. Below is a brief summary of the seminar modules.

Module I: Social Psychology and Social Neuroscience of Stigma

Readings from social psychology and social neuroscience literatures teach distinctions between social processes of stereotyping, stigma, prejudice, and discrimination, as well as the clinical use of relevant psychological constructs, such as social identity, identity flags, in-groups/out-groups, and group entitativity. Entitativity refers to an in-group’s level of organization, or “groupiness,” which primes a readiness to stigmatize out-group members. Experiential exercises help residents to apply these constructs to their personal experiences of stigmatization over the course of their lives.

As a group exercise, residents design a hypothetical new stigma by treating as a mark of stigma a selected behavior that might occur within the daily work lives of psychiatry residents. To illustrate this point, we have provided an excerpt from a resident exercise generating a credible stigma utilizing the following four-step “Stigma Generation Exercise”:

Think of a behavior that a psychiatry resident could display that plausibly would become stigmatized because it would disrupt the smooth and efficient functioning of residents working together as a group. As a representative behavior, the residents identified introduction of new clinical material for discussion just as end of day sign-out rounds were concluding. Hand-off of patient care to the night call team would then be unnecessarily lengthened by the poor organization and lack of thoughtfulness of the offending resident.

What might constitute an identity flag that would enable the rapid recognition of a resident showing this behavior? “Looking through papers”—as the sign-out discussion were ending, the offending resident would begin rummaging through notes from which to re-open discussion.

Think of ways that you could think about, talk about, and interact differently with that person so as to convey effectively that a resident with this mark of stigma is discredited as a person and now holds lower status within the whole group of residents. Other residents would “roll eyes” or look away when the offending residents would begin speaking and impatiently would interrupt comments. This could progress to omitting the resident from significant clinical conversations among residents.

Think of ways that this stigmatized resident could be discriminated against so that the espirit de corps of the larger group of residents would be lifted or the larger group would function more efficiently and effectively. Over time, invitations to resident social activities, such as “happy hours,” would cease for the offending resident. The resident also would be given “last picks” on switches among residents for weekend or holiday calls.

Residents who participated in the stigma generation exercise were surprised how quickly a credible stigma could be generated (less than 10 min), the intensity of emotion it evoked, and their lack of felt empathy towards the stigmatized resident. The exercise helped make the point that stigma is a social phenomena of normal people, not an indicator for mental illness.

Module II: Helping Patients to Anticipate and Manage Stigma in Family, Community, or Work Place Settings

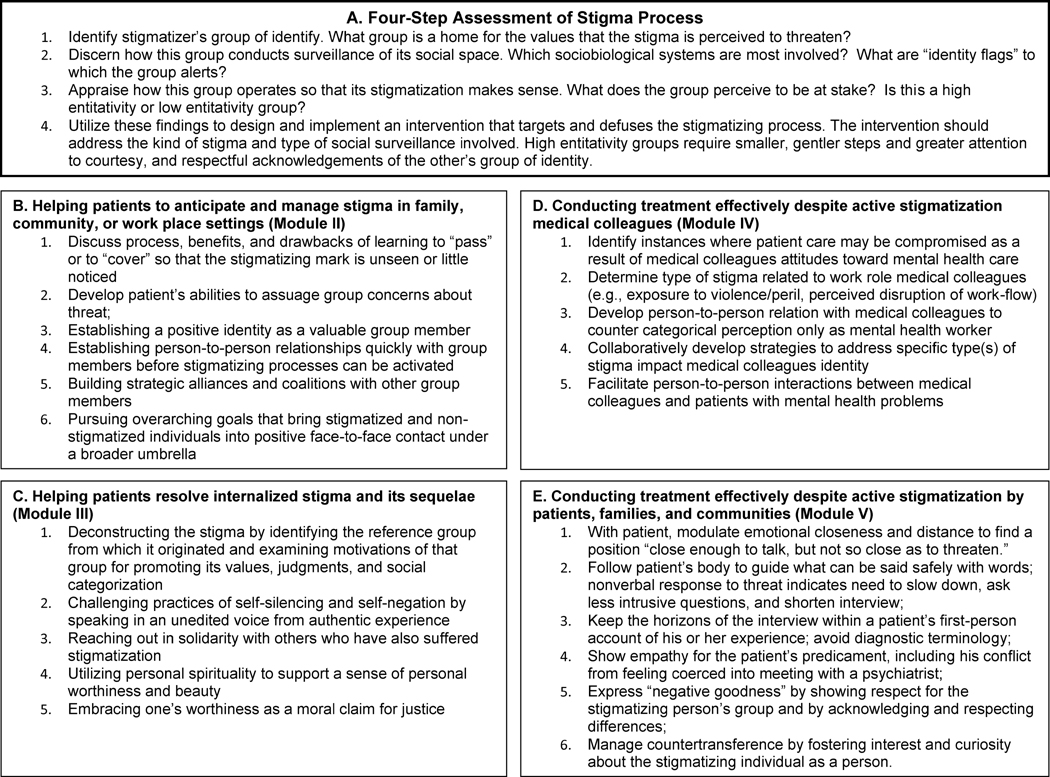

Residents learn how to assess, formulate, and design anti-stigma strategies by discerning first the stigmatizer’s group of identity. A person who stigmatizes someone acts primarily as a group member whose group of identity has been threatened. Moral stigma, disruption stigma, and courtesy stigma all share in common a sense of threat to the group of identity. Each group conducts defensive surveillance of its social space and does so uniquely depending upon what is perceived as vital to its interests. A strategy to counter stigma begins by appraising the methods a particular group uses to monitor threats to its security. The following four-step assessment prepares the groundwork for an anti-stigma strategy (see Fig. 1, box A).

Fig. 1.

Four-step assessment of stigma and application to common challenges in clinical settings

For designing interventions, residents study strategies that have been honed across the ages by individuals stigmatized for their ethnicity, religious beliefs, social class, or other social identity. Applications of these strategies have been validated in empirical social psychology research studies [2]. Figure 1 (box B) includes some of these strategies.

As an exercise, residents practice this assessment process by appraising a psychiatric patient’s risks for stigma, then tailoring an intervention that would anticipate and reduce the risk. This exercise was particularly suitable for inpatients approaching discharge back to home, community, and workplace.

Illustration: Ms. P. was a middle-aged woman admitted briefly to a psychiatric inpatient unit for depression. Conversations with Ms. P. revealed her impending reunion with her family and her return to her workplace to be potential concerns for stigmatization. However, the types of stigma differed. In her family, moral stigma was expressed, more by her siblings who viewed her depression as “weakness,” than by her husband and children. An identity flag in her family was “never asking for help,” and her babysitting requests when she felt overwhelmed had been treated as marks of stigma. At work, disruption stigma was the issue due to concerns that she might not be able to maintain reliable productivity. An identity flag in her office was “staying late until the job is done.” Leaving early from her workday or visits to her psychiatrist had been treated as marks of stigma. The psychiatry resident used role plays to practice with Ms. P. “what to say to whom” about her hospitalization, a plan to manage performance monitoring at work, and engaging her husband’s help in managing her siblings expectations.

Module III: Helping Patients Resolve Internalized Stigma and Its Sequelae

Residents study research literature on internalized stigma with its adverse impacts upon morale, relational lives, and treatment adherence for psychiatric patients. Role plays are used to practice psychotherapeutic strategies for recovery from internalized stigma by discovering aspects of oneself that are unsullied, intact, and worthy, while mobilizing defiance of the stigmatizing inner gaze. In manageable steps, patients practice steps of recovery (see Fig. 1, box C).

Illustration: Mr. D. was mired in social isolation and self disgust for his disability status from a recurrent mood disorder. Over the course of a brief psychotherapy, his psychiatry resident therapist focused detailed attention to the delicate caretaking he had provided for his orchids that were of remarkable beauty. Over the course of therapy, he slowly became able to experience this caretaking as a core sense of his identity, and, in time, to transfer the same care-taking to his personal wellbeing, with heightened self-regard and new relationships with others.

Module IV: Conducting Treatment Effectively Despite Active Stigmatization by Medical Colleagues

When residents feel stigmatized by a patient, patient’s family, or colleague, the residents’ attention focus upon the stigmatizing person’s group of identity, not the patient, family member, or colleague as an individual. The four-step assessment (module II) is conducted to determine type(s) of stigma and how that group’s social surveillance is conducted. Based upon this assessment, a strategy is designed and implemented to counter stigma against the mental health professional (see Fig. 1, box D).

Illustration: As a group, the PGY-III residency class felt most stigmatized, not by patients, but by medical colleagues such as by Emergency Medicine attendings who “hated psychiatry patients.” However, examination of multiple vignettes revealed two unexpected conclusions. First, peril stigma was an issue for some attendings who feared the unpredictable violence that occasionally occurred with psychotic patients. Second, both moral and disruption stigma emerged from hospital rules that Emergency Department attendings held authority to determine admissions for the medical and surgical services, but psychiatric admission decisions were made by the psychiatry resident. Emergency Medicine attendings were reacting both to a slow-down in speed for transferring patients out of the Emergency Department to the psychiatric unit by needing to consult first a psychiatry resident. They also reacted resentfully to what felt like a violation of hierarchy for an attending to ask permission from a resident. The PGY-III class brainstormed different strategies for oncall residents to structure differently how they interacted with Emergency Department attendings to minimize each of these stigma pathways.

Module V: Conducting Treatment Effectively Despite Active Stigmatization by Patients or Their Families—Helping Patients Access Care from Lay, Religious, or Other Healers When Professional Mental Health Treatment Risks Shunning or Extrusion by the Patient’s Group of Identity

Residents practice a four-step stigma assessment for patients or family members who stigmatize psychiatry. Case discussions examine how residents have implemented strategies for the stigmatized psychiatrist in clinical encounters where they have been stigmatized (see Fig. 1, box E). Key aspects of this process include showing empathy for the patient’s predicament, including the patient’s conflict from feeling coerced into meeting with a psychiatrist; expressing “negative goodness” by showing respect for the stigmatizing person’s group of identity and by acknowledging and respecting differences; creating a climate of safety by minimizing perceptions of threat; and meeting the stigmatizing person as a person, not as a category, by learning about the stigmatizing individual as a complex person possessing unique ideas, emotions, and actions. The following vignette illustrates how clinical work can be conducted effectively from a stigmatized position, including efforts to help the patient to find resources within his group of identity ([16], pp. 144–147):

Mr. B. was a young man for whom psychiatric consultation had been requested due to jerking movements diagnosed as psychogenic movement disorder by the consulting neurologist. As the psychiatric consultant entered the room, he sat up vigilantly in his bed, with a hostile demeanor and minimal politeness.

The psychiatric consultant realized that Mr. B. felt humiliated by the presence of a psychiatrist in his care, which was further evident in his vigorous denial of any current life stressors or past psychiatric symptoms or treatment. Mr. B. had struggled with severe diabetes since childhood.

The consultant inquired about Mr. B’s own theory as to the origins and meaning of his medically unexplained symptoms. Mr. B. responded angrily, telling how his internist had confronted him with an abrupt accusation “there is nothing wrong with you,” after medical tests reported normal findings. Mr. B. felt stunned, betrayed, and bitterly angry. He fired the doctor but then felt lost and confused where to turn next. He eventually found his way to the GWU Neurology Department. The consultant observed how Mr. B.’s wariness was diminishing as he spoke from his personal experience. The consultant expressed empathy for B.’s frustration with his medical caregivers, then asked an existential question to draw Mr. B.’s motivations, values, and commitments into the discussion: “You are shouldering a lot—diabetes is a chronic disease that requires more and more care as one grows older, and it must take a lot of work to manage this plus the episodes of jerking, and especially so since the doctors to whom you have turned had been of no help. What has kept you from giving up or being overwhelmed by all this?”

Mr. B. described how he attempted to utilize his religious faith, including counseling from a religious professional, to cope with problems in his life. He had attempted “to beat his body into submission.” The psychiatric consultant kept his formulation of the problem within Mr. B.’s religious discourse:

“Perhaps you are locked in spiritual warfare between your desire to live a life of the spirit and the desires of the flesh. The tension produced might be making your body ill… There might be other possibilities beside beating the flesh into submission or letting the flesh take over… I am concerned that as you have tried to exert tighter and tighter control over your feelings, the struggle and tension has increased, not lessened, and it is making your body ill.”

While this formulation might have provided a reasonable rationale for referring Mr. B. for psychotherapy, the psychiatric consultant also realized that Mr. B.’s conservative religious community would likely shun him were he to go outside the religious community for help. He sought instead to organize a recommendation within resources of Mr. B.’s religious ingroup: “If this idea has any merit, then I would recommend that you work with someone who can understand what you are struggling with, not try to do it alone. Psychotherapy with a mental health professional who understands and respects your faith could be one option. Perhaps seeing a pastoral counselor who understands how a spiritual struggle might make the body ill could be another possibility. I’ll bet you know Christians who do not have this kind of warfare going on within them. If you were to spend time with someone who is older and has lived a lot of years, there might be things you could learn.” Whereas treatment by a psychiatrist or psychologist would be unacceptable within his group, a psychologically mature elder in his church might be better positioned for this role than a mental health professional.

Seminar Outcome Assessment

The seminar began as part of a programmatic effort to ground the GW psychiatry residency in neuroscience research [9]. In its first 4 years from 2009–2012, it was taught at the PGY-III level, utilizing readings and handouts to teach clinical concepts of stigma together with brain circuitry for dual social cognition systems, in similar manner to the current manuscript. However, seminar outcome assessments found that residents had gained significant cognitive knowledge about stigma but were failing to translate it into practical interventions in clinical encounters [10]. The seminar was retired for a year and re-drafted to translate knowledge about stigma into teachable practices.

The current 2014 seminar was taught with 11 PGY-III and PGY-IV residents in a combined group. Residents in this group were all US medical school educated but highly diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, race, religious identity, and sexual identity. A draft of the current manuscript was utilized as a core text so that residents’ evaluation of the seminar could also serve as a direct evaluation of the teaching model. Readings were completed outside of class, and lecture time for each session was limited to a 15-min review of key principles. The remaining 75 min of each session were fully spent with small group skill-building exercises that practiced stigma assessment, formulation, and intervention for different types of stigma in different contexts, employing role plays and enactments drawn from encounters with stigma in residents’ personal lives, GWU Hospital psychiatric services, or outpatient community clinics.

The educational impact of the 2014 seminar was assessed utilizing multiple methods that included the following:

In-Session Observed Assessments of Cognitive Learning—Reviews of core concepts and key ideas were conducted weekly with the full group. For example, residents were queried in group discussions: (1) to define stigma and its key attributes, (2) to explain how stigma is generated via categorical social cognition, (3) to describe the four steps for stigma assessment, formulation, and intervention, and (4) to describe multiple types of intervention strategies.

In-Session Observed Assessments of Procedural Learning—Small group memberships were changed weekly. Each group performed four-step stigma assessment, formulation, and intervention exercises utilizing different case examples in role played enactments until accrual of a level of competency was observed.

-

Post-Seminar Assessment of Learning by Individuals— An end of seminar assessment provided confidential feedback from individual residents.

Global rating for educational effectiveness of seminar was 8.0 (range 6.0–9.0) on a zero-to-ten Likert scale;

Nearly 50 % of respondents posted positive narrative comments on use of role plays and enactments as training tools;

Comments for improvements included additional readings, greater structure, and additional sessions per module;

One respondent requested 10-min decompression time at the end of each session to process difficult emotions that arose during the exercises.

-

Post-Seminar Assessment of Learning with Focus Group—A focus group of all residents was used to identify strengths, accomplishments, and challenges.

What was any useful new learning that you gained from the seminar? First, learning that stigma against mental illness can exist in multiple different categories, such as peril stigma, moral stigma, or disruption stigma; second, gaining confidence that one can possess tools for managing stigma effectively; third, learning the effectiveness of person-to-person contact in attenuating stigma; and fourth, learning to describe different steps in social cognition that underlie stigma, which provides a way to talk about stigma in clinical discussions.

In what settings have you employed this new learning? Two outpatient community mental health center training sites were named where residents were making efforts specifically to address internalized stigma among patients with chronic psychiatric illnesses. A resident commented that the seminar let her to become more aware of how she might be perceived by her patients in terms of social categorization. Another commented that the seminar “helped me figure out when I was stigmatizing.”

Have there been problems or challenges with stigma for which the seminar did not provide sufficient help? The main challenge identified was how to help a patient stigmatized by family members when the family took no role in the patient’s treatment.

What was your experience of participating in the role plays, enactments, and discussions involving stigma and prejudice? Here, residents’ responses reflected ambivalence. The exercise experiences brought home the power of group identity and categorical social cognition and the emotional impact of stigmatization. One resident commented, “It can be good to remember. You draw closer to people in your group and try to prove the others wrong.” However, another resident said, “It is hard to think about and talk about how I’ve been stigmatized. It doesn’t draw me closer to others,” and another responded, “Learning how to intervene is good, but it brings up a lot of anger that I have to do it.” Several residents told how the exercises that focused on group identity also made them more aware of group identities among the residents, which created a sense of separateness.

In summary, the in-session assessments of learning confirmed by observation the learning of critical cognitive information, as well as procedural learning for stigma management in varied enactments and role plays. The post-seminar focus group assessment demonstrated specific clinical sites and settings where residents were implementing learning in practice, with residents’ reporting specific clinical successes in terms of the following: (1) possessing specific tools with which to counter stigma effectively, which empowered residents’ sense of effectiveness; (2) enabling residents to conduct successfully some difficult clinical encounters that stigma might otherwise have compromised; (3) providing language for describing and discussing stigma as a difficult social process, i.e., “making explicit the implicit” in an inpatient rounds discussion of a case where stigma was impacting patient care; and (4) heightening self-awareness of one’s participation in stigmatizing processes, e.g.,. “helped me figure out when I was stigmatizing.” It is important to note that experiences of participating in training exercises that evoked past personal experiences of stigmatization were felt both to be valuable and emotionally distressing.

Conclusion

Stigma against psychiatry, psychiatrists, and individuals bearing mental illnesses is universal among human societies. Social psychology and social neuroscience can provide an understanding of stigma that yields more effective methods for assessing, formulating, and implementing interventions for countering stigma. This social psychology and social neuroscience perspective helps identify steps in stigma generation where targeted interventions are most likely to be effective. It distinguishes multiple kinds of stigmatizing processes so that interventions can be more specifically tailored. It also helps set more realistic expectations for what can be accomplished with programs of education, which have limited effectiveness with implicit cognitive processes of interpersonal stigma, but greater effectiveness with explicit cognitive processes of institutionalized stigma and discrimination. It is teachable in a residency seminar that blends didactic study with experiential and group-learning exercises. This approach to breaking down stigma into different types of threats and employing social psychology may also benefit public campaigns to reduce stigma against mental illness. To date, public campaigns that use neuroscience to explain the etiology of mental illness have limited and even exacerbating effects on stigma [6]. Instead, social neuroscience theory could be employed with the public as we have done with residents. There is preliminary support for this as evidenced by positive outcomes for an anti-stigma module employing these same principles which we included in a mental health training for police officers in Liberia [22]. Future efforts for neuroscience-based training in reducing and managing stigma should evaluate the impact of these curricula on trainee behaviors, clinical practices, and patient outcomes.

Implications for Educators.

Residents need skills sets for countering stigma during interpersonal encounters with stigmatizing patients, families, and medical colleagues.

Curricula are needed to prepare residents to integrate knowledge of neurobiology to reduce stigma, which is a highest tier competency (level 5) for Clinical Neuroscience (milestone 3) in the ACGME Milestones for Psychiatry.

Mental health trainees can be taught to improve managing stigma by categorizing stigma according to peril threats, disruption threats, empathy fatigue, and moral threats.

Effective stigma management strategies incorporate reducing arousal to threat and shifting interpersonal interactions from categorical social cognition to person-to-person social cognition.

Social neuroscience and social psychology research can be used to understand stigma within the healthcare system and to manage stigma against mental health clinicians from medical colleagues.

Further research is needed to evaluate the impact of social neuroscience-based stigma reduction on clinical practices and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The second author (BAK) has received funding support through NIMH U19 MH095687 and NIMH K01 MH104310.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrigan PW, Kosyluk KA. Mental illness stigma: types, constructs, and vehicles for change. In: Corrigan PW, editor. The stigma of disease and disability. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sartorius N, Gaebel W, Cleveland H-R. WPA guidance on how to combat stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:131–44. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuart H, Arboleda-Florez J, Sartorius N. Paradigms lost: fighting stigma and the lessons learned. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, et al. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:963–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, et al. “A disease like any other”? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatr. 2010;167:1321–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harmon-Jones E, Winkielman P. Social neuroscience: integrating biological and psychological explanations of social behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACGME/ABPN. The psychiatry milestone project: the accreditation council for graduate medical education, and the American board of psychiatry and neurology. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith JL. Neuroscience and humanistic psychiatry: a residency curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38:177–84. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith JL. Teaching psychiatry residents how to manage stigma: a curriculum grounded in social neuroscience and the social psychology of stigma. 40th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training; Austin, Texas. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith JL. Workshop: Interviewing patients who hate or fear psychiatrists. 163rd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; New Orleans. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones E, Farina A, Hastorf H, et al. Social stigma: the psychology of marked relationships. New York: Freeman; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Fiske S, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurzban R, Leary MR. Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: the functions of social exclusion. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:187. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beer J, Mitchell J, Ochsner K. Multiple perpsectives on the psychological and neural bases of social cognition. Brain Res. 2006;1079:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith JL. Religion that heals, religion that harms: a guide for clinical practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiao JY. Neural basis of social status hierarchy across species. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:803–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Botvinick M, Braver T, Barch D, et al. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol Rev. 2001;108:624–52. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene JD, Nystrom LE, Engell AD, et al. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgement. Neuron. 2004;44:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiaramelli E, Sperotto R, Mattioli F, et al. Damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortext reduces interpersonal disgust. SCAN. 2013;8:171–80. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decety J, Yang C-Y, Cheng Y. Physicians down-regulate their pain empathy response: an event-related brain potential study. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohrt BA, Blasingame E, Compton MT, et al. Adapting the crisis intervention team (CIT) model of police–mental health collaboration in a low-income, post-conflict country: curriculum development in Liberia, West Africa. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e73–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]