Abstract

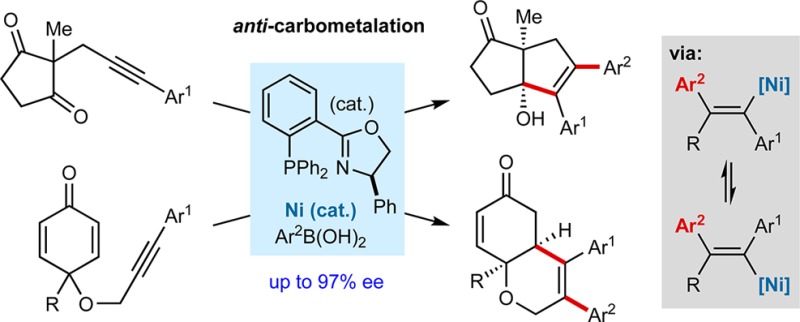

Nickel-catalyzed additions of arylboronic acids to alkynes, followed by enantioselective cyclizations of the alkenylnickel species onto tethered ketones or enones, are reported. These reactions are reliant upon the formal anti-carbonickelation of the alkyne, which is postulated to occur by the reversible E/Z isomerization of an alkenylnickel species.

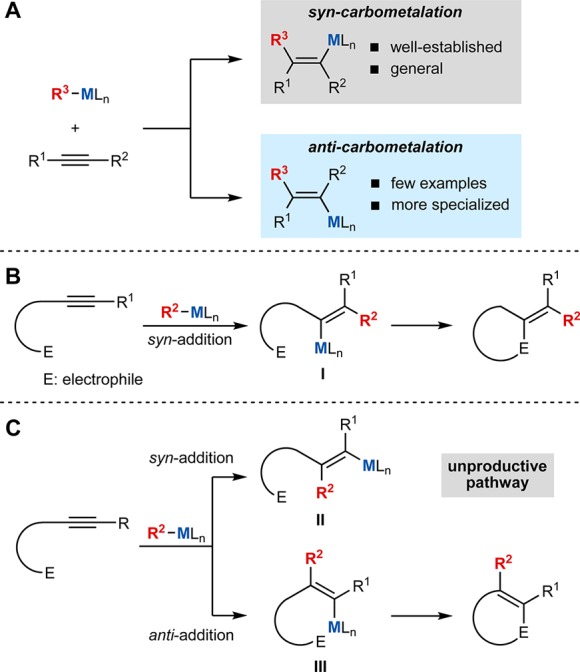

Transition-metal catalysis is utilized extensively in organic synthesis to prepare compounds required for numerous applications such as drug discovery, agrochemistry, and materials science. Despite the diversity of known transition-metal-catalyzed reactions, they all operate using combinations of only a few elementary organometallic reaction steps. One of these is the 1,2-insertion of a π-unsaturated component into a metal–element bond, which, owing to strict stereoelectronic requirements, is syn-selective. When applied to the migratory insertion of an alkyne with an organometallic species, this prevailing stereochemical principle (Figure 1A, top) provides a reliable route to stereodefined alkenes, a feature that has been exploited in numerous synthetic methods.1 Although anti-selective alkyne carbometalations (Figure 1A, bottom) would offer valuable new synthetic opportunities, such processes are uncommon.2

Figure 1.

Carbometalation of alkynes and alkynyl electrophiles.

One strategy to obtain alkenylmetal species resulting from formal anti-carbometalation is to employ substrates with a heteroatom-containing substituent in close proximity to the alkyne. After syn-carbometalation, E/Z isomerization to the anti-isomer is driven by the formation of a more stable, chelated alkenylmetal species, in which the metal is coordinated to the heteroatom.1b,2a,2b,2d,2h Although effective, the requirement for a nearby heteroatom-containing group limits broader applicability. Other reactions that provide anti-carbometalation products proceed via alternative mechanisms involving radical intermediates, but the substrates are restricted to terminal alkynes.2j−2n,3 In addition, with only a few exceptions,2h,2l−2n both of the aforementioned approaches require stoichiometric quantities of more reactive organometallics such as Grignard or organozinc reagents, which limit functional group compatibility and require rigorous exclusion of air and moisture. Furthermore, the integration of these processes into enantioselective reactions has not been reported. Given these issues, developing new platforms to access alkenylmetal species derived from anti-carbometalation of a wider range of alkynes, using organometallic reagents that exhibit high functional group tolerance, and in a manner that is amenable to asymmetric catalysis, would likely be of broad impact. Here, we describe enantioselective nickel-catalyzed domino alkyne carbometalation–cyclizations in which the products are derived from formal anti-carbonickelation of the alkyne. The reactions use simple internal aryl-substituted alkynes and air- and moisture-stable arylboronic acids.

This study arose when we became interested in the enantioselective domino addition–cyclization of alkynyl electrophiles (Figure 1B), which are valuable complexity-generating transformations.4 These reactions involve the syn-1,2-addition of an organometallic species across an alkyne to place the metal proximal to the electrophile (as in I), which enables cyclization to take place.5 However, if syn-carbometalation proceeds to place the metal distal to the electrophile (as in II), cyclization is not possible due to geometric constraints (Figure 1C).6 An anti-carbometalation of the alkyne would provide a solution to this problem, as now the resulting alkenylmetal species III possesses the correct geometry for cyclization (Figure 1C). However, overcoming the inherent syn-selectivity of alkyne migratory insertion is a considerable challenge.

A previous study has shown that the stoichiometric addition of organonickel complexes to simple alkynes that do not contain a nearby heteroatom-containing functional group can lead to alkenylnickel species resulting from formal anti-addition, although not always exclusively.2c A single example of the cobalt-catalyzed addition of an arylboronic acid to a symmetrical dialkyl alkyne to give a trisubstituted alkene as a 1:1 mixture of E/Z isomers has also been reported.2h In each case, the authors propose an initial syn-addition across the alkyne followed by reversible E/Z isomerization to give products of overall anti-addition.2c,2h Despite the potential significance of these findings, more widespread applications to organic synthesis, such as addressing the gap in methodology outlined in Figure 1C, have yet to be reported.7

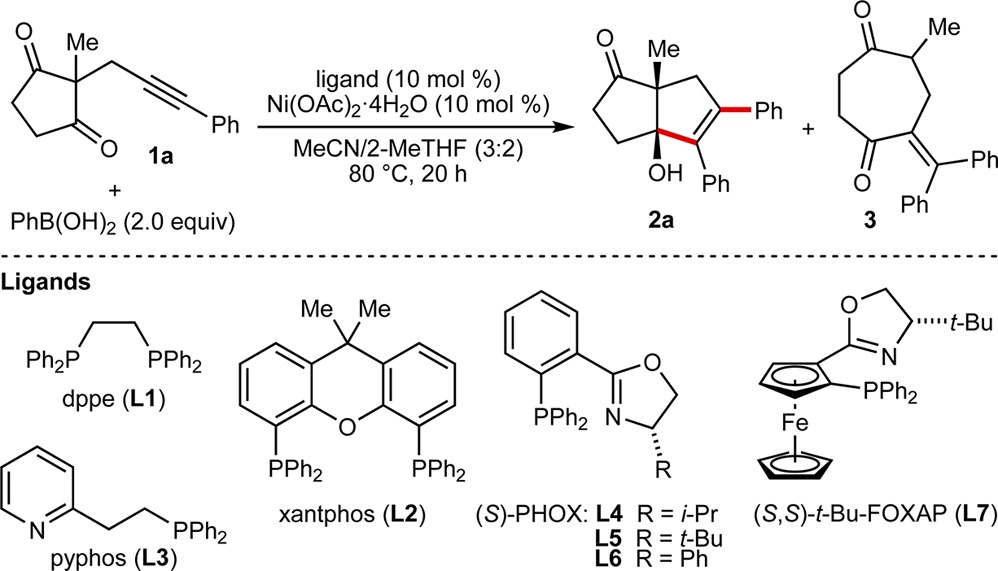

We began by reacting alkynone 1a with PhB(OH)2 (2.0 equiv) in the presence of various cobalt and nickel salts, with or without added ligands. These experiments revealed that nickel catalysis gave promising results. For example, Ni(OAc)2·4H2O (10 mol %) by itself was effective in promoting anti-arylmetallative cyclization at 80 °C in MeCN/2-MeTHF (3:2) to give 5,5-bicycle 2a in 39% NMR yield (Table 1, entry 1).8 Arylative cyclization via 1,4-metal migration, as we have described using iridium catalysis,9 was not observed. Although the addition of dppe (L1) increased the NMR yield of 2a to 64%, an appreciable quantity of the ring-expansion product 3 was also formed, which is derived from arylnickelation of the alkyne of 1a with the regioselectivity opposite to that seen in the formation of 2a (entry 2).9,10 Xantphos (L2) was inferior to dppe (L1) (entry 3), but the P,N-ligand L3 was much more effective and gave 2a in 87% NMR yield with only a small quantity of 3 (entry 4). Furthermore, by using commercially available chiral phosphinooxazoline ligands11L4–L7, 2a was obtained in 63–97% ee (entries 5–8). Ligands L5 and L7 gave the highest enantioselectivities but the yields were modest (entries 6 and 8). (S)-Ph-Phox (L6) gave the best balance of yield and enantioselectivity (entry 7).

Table 1. Evaluation of Reaction Conditionsa.

| entry | ligand | yield of 2a (%)b | yield of 3 (%)b | ee of 2a (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 39 | 0 | – |

| 2 | L1 | 64 | 30 | – |

| 3 | L2 | 36 | 0 | – |

| 4 | L3 | 87 | 7 | – |

| 5 | L4 | 90 | 9 | 63 |

| 6 | L5 | 56 | 4 | 93 |

| 7 | L6 | 95 | 5 | 86 |

| 8 | L7 | 33 | 3 | 97 |

Reactions employed 0.10 mmol of 1a.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reactions, using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

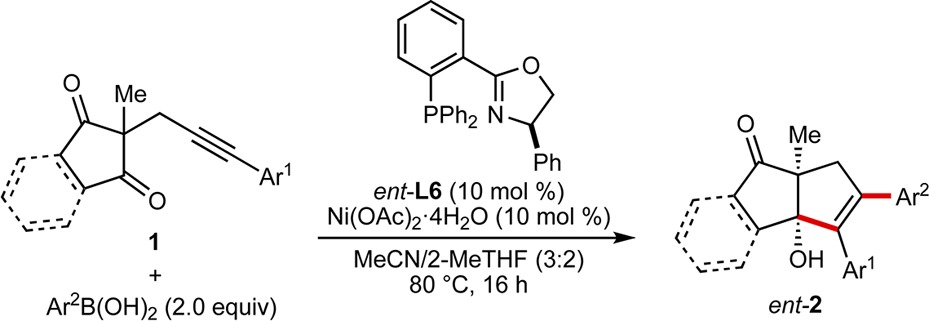

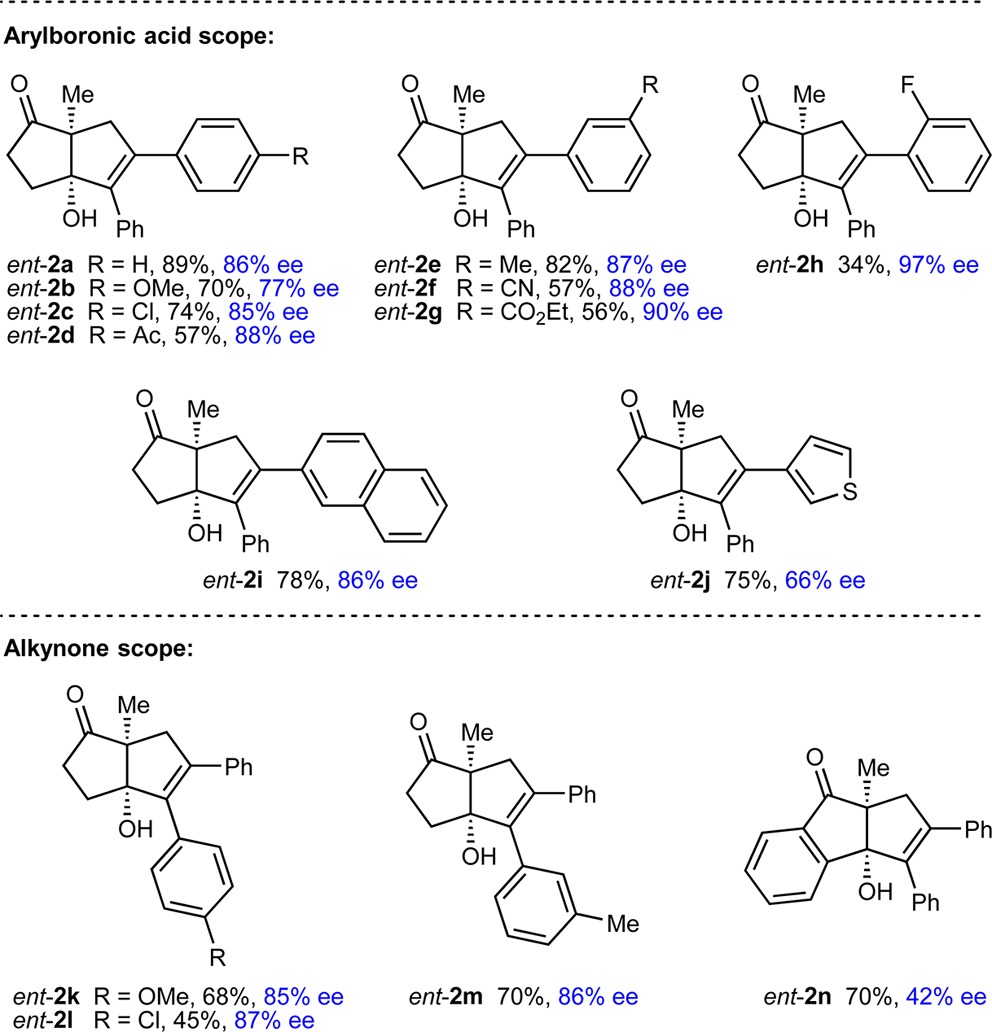

The scope of this process was then examined using (R)-Ph-Phox (ent-L6) as the ligand (Table 2). By variation of the arylboronic acid and alkynone, products ent-2a–2n were obtained in 34–89% yield and 42–97% ee. The reaction is compatible with para- (ent-2a–2d), meta- (ent-2e–2g), and ortho-substituted (ent-2h) arylboronic acids, and the functional group tolerance is shown by examples with methoxy (ent-2b), halide (ent-2c and ent-2h), acetyl (ent-2d), nitrile (ent-2f), or carboethoxy (ent-2g) substituents. 2-Naphthylboronic acid (ent-2i) and a heteroarylboronic acid (ent-2j) are also tolerated. Variation of the alkynyl substituent to other aryl groups is possible (ent-2k–2m), but terminal alkynes provide complex mixtures of unidentified products. Use of an indan-1,3-dione-containing substrate gave ent-2n in 70% yield but in 42% ee. No reaction was observed using alkenylboronic acids or with substrates containing alkynes bearing methyl or trimethysilyl groups in place of aryl groups.12

Table 2. Scope of Five-Membered Cyclic 1,3-Diketonesa.

Reactions employed 0.30 mmol of 1. Yields are of isolated products. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

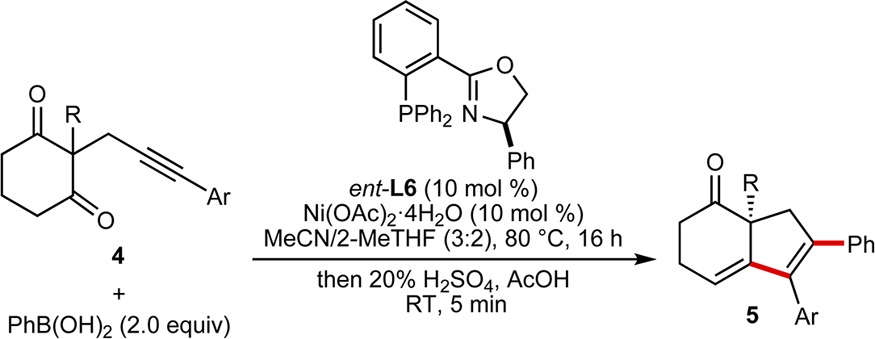

When the cyclic 1,3-diketone was changed to a cyclohexane-1,3-dione, significant dehydration of the initial cyclization products to give 1,3-dienes 5 was observed. The unpurified mixtures were therefore treated with 20% H2SO4 in AcOH to drive dehydration to completion (Table 3). Using this procedure, substrates 4 with various substituents at the alkyne and the 2-position of the cyclohexane-1,3-dione gave dienes 5a–5f in 37–79% yield and 88–97% ee.

Table 3. Scope of Six-Membered Cyclic 1,3-Diketonesa.

Reactions employed 0.30 mmol of 4. Yields are of isolated products. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

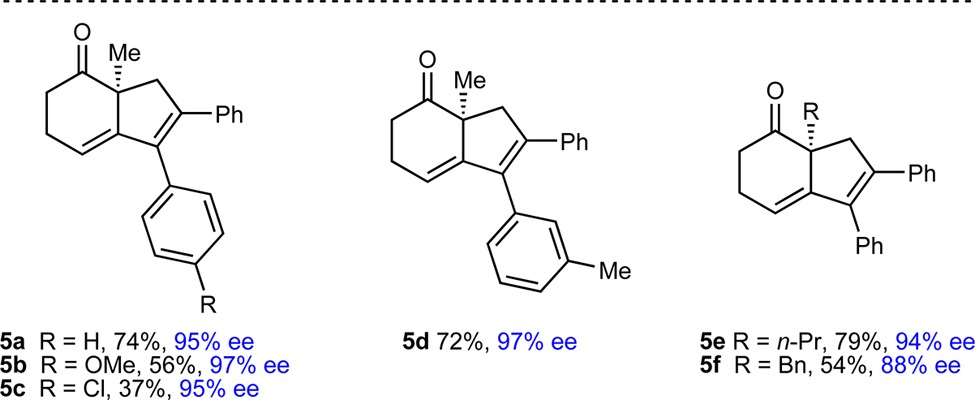

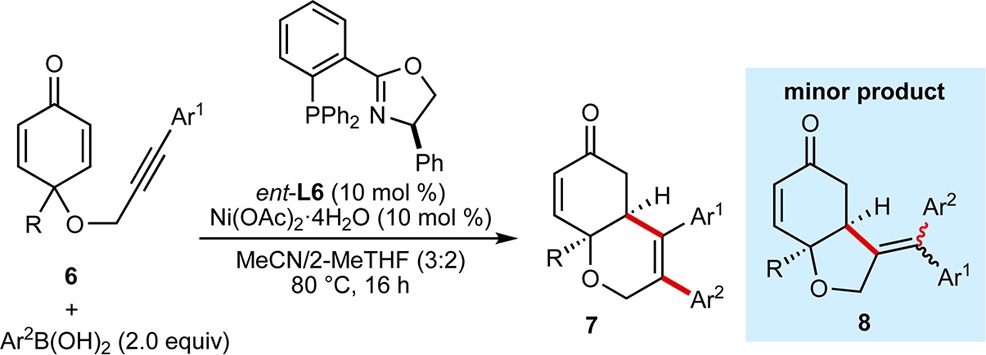

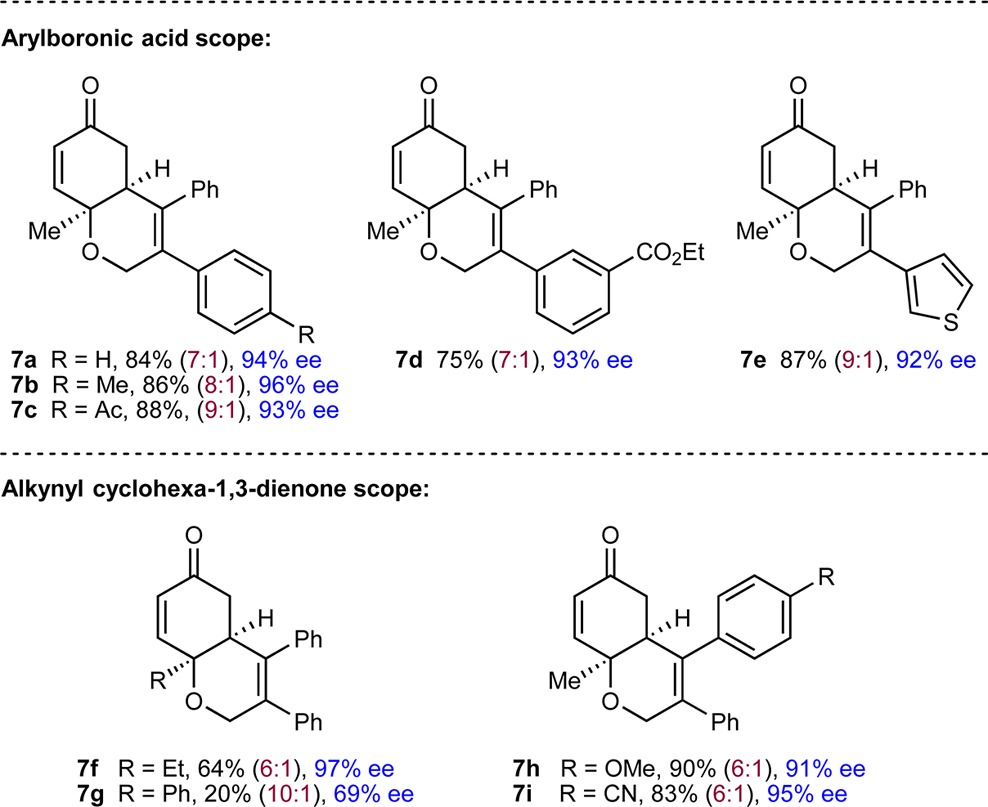

Notably, this process is not limited to cyclic 1,3-diketones as the electrophilic trap, as substrates containing alkynes tethered to a cyclohexa-1,3-dienone are also highly effective (Table 4). For example, various arylboronic acids reacted with 6a (R = Me, Ar1 = Ph) to give 6,6-bicycles 7a–7i in 20–90% yield and 69–97% ee. These products were isolated together with small quantities of minor products 8, which result from arylnickelation of the alkyne with the regioselectivity opposite to that seen in the formation of the major products 7. Changing the substituent at the quaternary center (7f and 7g) or the alkyne (7h and 7i) is also possible.

Table 4. Scope of Alkynyl Cyclohexa-1,3-dienonesa.

Reactions employed 0.30 mmol of 6. Yields are of isolated products. Ratios in parentheses refer to the ratio of 7:8 as determined by 1H NMR analysis after purification. Enantiomeric excesses are of the major products 7a–7i as determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

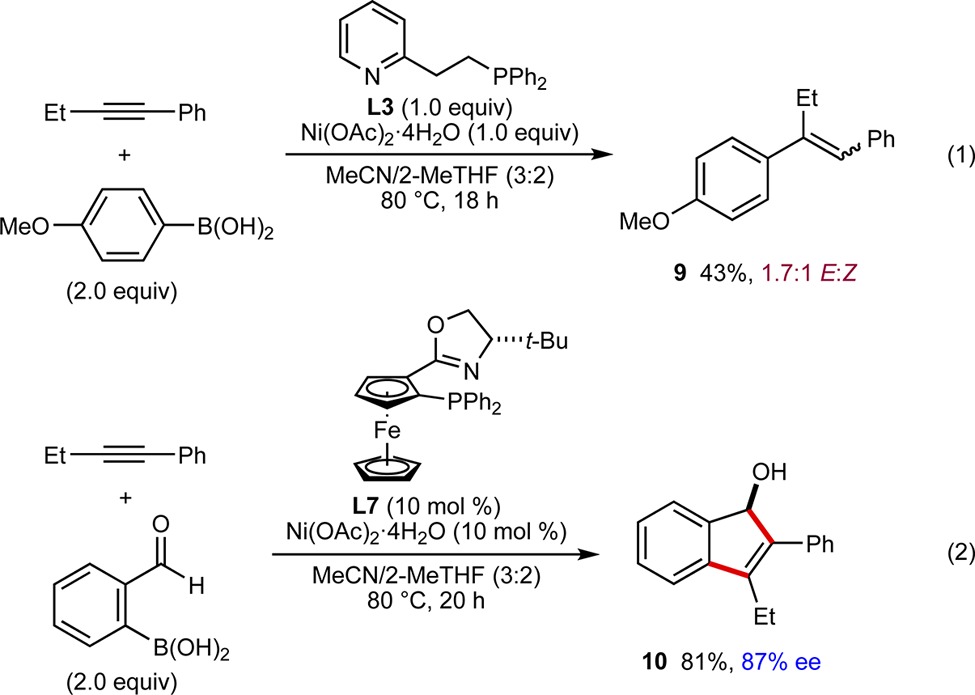

To gain insight into the mechanism of these reactions, the reaction of 1-phenyl-1-butyne with 4-methoxyphenylboronic

|

1 |

acid in the presence of 1.0 equiv each of Ni(OAc)2·4H2O and L3 was conducted (eq 1). This experiment gave trisubstituted alkene 9 as a 1.7:1 mixture of E- and Z-isomers, respectively, along with traces of isomers derived from arylnickelation with the opposite regioselectivity. As well as demonstrating the ability of nickel catalysis to provide anti-carbometalation products from alkynes that do not contain a tethered electrophile, this experiment suggests that the domino reactions described herein proceed through a mechanism similar to that shown in Figure 1C, rather than one involving initial “anti-Wacker-type” additions.6 The reaction of 1-phenyl-1-butyne with 2-formylphenylboronic acid using L7 as the chiral ligand (see Table 1, entry 8 for the use of L7 in anti-carbometallative cyclization) gave indene 10 in 81% yield and 87% ee (eq 2), which is a product of syn-arylnickelation of the alkyne followed by cyclization of the resulting alkenylnickel species onto the aldehyde.13 The ability to obtain enantioenriched products from either syn- or anti-carbometallative cyclization illustrates the adaptive power of this nickel-based catalytic system and further suggests that reversible E/Z isomerization of alkenylnickel species is operative.

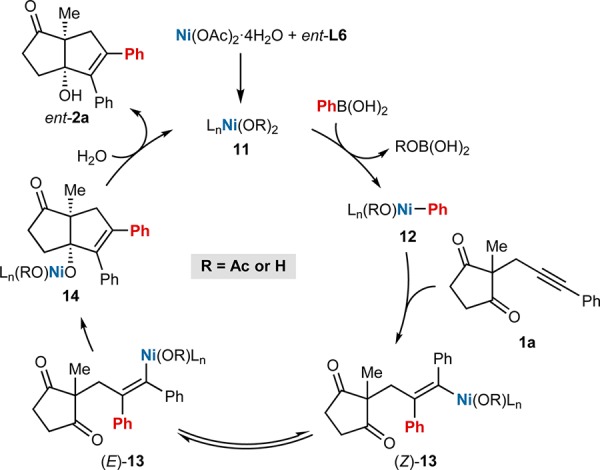

On the basis of these experiments, we propose a catalytic cycle for a representative example of anti-carbometallative cyclization, using alkynone 1a with PhB(OH)2 (Scheme 1). Transmetalation of PhB(OH)2 with the nickel complex 11 formed from Ni(OAc)2·4H2O and ent-L6 gives an arylnickel species 12. Syn-arylnickelation of 1a with 12 gives the alkenylnickel intermediate (Z)-13, which can undergo reversible E/Z isomerization,2c,14 to give a new alkenylnickel species (E)-13. Cyclization of (E)-13 onto one of the ketones gives nickel alkoxide 14, which can undergo protonolysis with water to release the product 2a and regenerate nickel complex 11. Presumably, cyclization drives the equilibrium between (Z)-13 and (E)-13 toward the E-isomer. We assume a similar pathway is operative in the cyclizations of alkynyl cyclohexa-1,3-dienones (Table 4), with protonation of the nickel enolate formed by intramolecular 1,4-addition of the intermediate alkenylnickel species being the likely catalyst turnover step.

Scheme 1. Postulated Catalytic Cycle.

In conclusion, we have established that products of formal anti-carbometalation of alkynes can be obtained by exploiting the ability of alkenylnickel intermediates to undergo reversible E/Z isomerization and have demonstrated the utility of this method in promoting previously inaccessible domino reactions with high enantioselectivities. We expect this underexplored mode of reactivity may have significant untapped potential, and its creative use in other contexts may lead to further new applications in organic synthesis.7

Acknowledgments

We thank the ERC (Starting Grant no. 258580), EPSRC (Leadership Fellowship to H.W.L.; grants EP/I004769/1 and EP/I004769/2), the University of Nottingham, and GlaxoSmithKline for support of this work. We thank Dr. Benjamin M. Partridge (University of Sheffield) for helpful suggestions. We are grateful to Dr. William Lewis (University of Nottingham) for X-ray crystallography.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b04206.

Author Contributions

‡ These authors contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For reviews, see:; a Normant J. F.; Alexakis A. Synthesis 1981, 1981, 841. 10.1055/s-1981-29622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fallis A. G.; Forgione P. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 5899. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00422-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Marek I.; Chinkov N.; Banon-Tenne D.. Carbometallation Reactions; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, 2008. [Google Scholar]; d Ding A.; Guo H. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis II, 2nd ed.; Knochel P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2014; pp 891–938. [Google Scholar]

- a Jousseaume B.; Duboudin J.-G. J. Organomet. Chem. 1975, 91, C1. 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)91880-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Duboudin J. G.; Jousseaume B.; Saux A. J. Organomet. Chem. 1979, 168, 1. 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)91989-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Huggins J. M.; Bergman R. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 3002. 10.1021/ja00401a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Ma S.; Negishi E.-i. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 784. 10.1021/jo9622688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Jia C.; Lu W.; Oyamada J.; Kitamura T.; Matsuda K.; Irie M.; Fujiwara Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7252. 10.1021/ja0005845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Lu Z.; Ma S. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 2655. 10.1021/jo0524021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Fressigné C.; Girard A.-L.; Durandetti M.; Maddaluno J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 891. 10.1002/anie.200704139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Lin P.-S.; Jeganmohan M.; Cheng C.-H. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 11296. 10.1002/chem.200801858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Yang Y.; Wang L.; Zhang J.; Jin Y.; Zhu G. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 2347. 10.1039/c3cc49069f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Cheung C. W.; Zhurkin F. E.; Hu X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4932. 10.1021/jacs.5b01784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Cheung C. W.; Hu X. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21, 18439. 10.1002/chem.201504049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Li Z.; García-Domínguez A.; Nevado C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11610. 10.1021/jacs.5b07432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m He Y.-T.; Wang Q.; Li L.-H.; Liu X.-Y.; Xu P.-F.; Liang Y.-M. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5188. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Li Z.; García-Domínguez A.; Nevado C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6938. 10.1002/anie.201601296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- After the submission of this paper, a palladium-catalyzed anti-carboperfluoroalkylation of internal alkynes was reported:Domański S.; Chaładaj W. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3452. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Shintani R.; Okamoto K.; Otomaru Y.; Ueyama K.; Hayashi T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 54. 10.1021/ja044021v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Miura T.; Shimada M.; Murakami M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1094. 10.1021/ja0435079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Miura T.; Sasaki T.; Nakazawa H.; Murakami M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1390. 10.1021/ja043123i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Shintani R.; Tsurusaki A.; Okamoto K.; Hayashi T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3909. 10.1002/anie.200500843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Song J.; Shen Q.; Xu F.; Lu X. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2947. 10.1021/ol0711772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Han X.; Lu X. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 108. 10.1021/ol902538n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g He Z.-T.; Tian B.; Fukui Y.; Tong X.; Tian P.; Lin G.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5314. 10.1002/anie.201300137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Keilitz J.; Newman S. G.; Lautens M. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 1148. 10.1021/ol400363f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Li Y.; Xu M.-H. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2712. 10.1021/ol500993h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Johnson T.; Choo K.-L.; Lautens M. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 14194. 10.1002/chem.201404896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of enantioselective, transition-metal-catalyzed addition–cyclizations of alkynyl electrophiles that proceed through metallacyclic intermediates, see:; a Rhee J. U.; Krische M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 10674. 10.1021/ja0637954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tanaka R.; Noguchi K.; Tanaka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1238. 10.1021/ja9104655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Masuda K.; Sakiyama N.; Tanaka R.; Noguchi K.; Tanaka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6918. 10.1021/ja201337x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Fu W.; Nie M.; Wang A.; Cao Z.; Tang W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2520. 10.1002/anie.201410700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For nonenantioselective palladium-catalyzed domino cyclization–additions of alkynyl electrophiles that proceed by “anti-Wacker” additions, see:; a Tsukamoto H.; Ueno T.; Kondo Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1406. 10.1021/ja056458o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tsukamoto H.; Ueno T.; Kondo Y. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3033. 10.1021/ol071107v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tsukamoto H.; Kondo Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4851. 10.1002/anie.200800823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- After the submission of this paper, a nickel-catalyzed anti-carbometallative cyclization of alkynyl nitriles was reported:Zhang X.; Xie X.; Liu Y.. Chem. Sci., 2016, 7, Advance Article, 10.1039/C6SC01191H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The relative and absolute configurations of the products were assigned by analogy with those of ent-2c, ent-2i, 7a, and 10 which were determined by X-ray crystallography. See the SI for details.

- Partridge B. M.; Solana González J.; Lam H. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6523. 10.1002/anie.201403271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T.; Shimada M.; Murakami M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7598. 10.1002/anie.200502650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a von Matt P.; Pfaltz A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 566. 10.1002/anie.199305661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sprinz J.; Helmchen G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 1769. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60774-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Allen J. V.; Coote S. J.; Dawson G. J.; Frost C. G.; Martin C. J.; Williams J. M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1994, 2065. 10.1039/p19940002065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- However, replacing ent-L6 with L3 did lead to productive reactions with varying degrees of success. See the SI further details.

- a Shintani R.; Okamoto K.; Hayashi T. Chem. Lett. 2005, 34, 1294. 10.1246/cl.2005.1294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yang M.; Zhang X.; Lu X. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5131. 10.1021/ol702503e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yamamoto A.; Suginome M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15706. 10.1021/ja055396z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Daini M.; Yamamoto A.; Suginome M. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2, 968. 10.1002/ajoc.201300164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.