Abstract

Objective Despite the current prevalence of preterm births, no clear guidelines exist on the optimal mode of delivery. Our objective was to investigate the effects of mode of delivery on neonatal outcomes among premature infants in a large cohort.

Study Design We applied a retrospective cohort study design to a database of 6,408 births. Neonates were stratified by birth weight and a composite score was calculated to assess neonatal outcomes. The results were then further stratified by fetal exposure to antenatal steroids, birth weight, and mode of delivery.

Results No improvement in neonatal outcome with cesarean delivery (CD) was noted when subjects were stratified by mode of delivery, both in the presence or absence of antenatal corticosteroid administration. In the 1,500 to 1,999 g subgroup, there appears to be an increased risk of respiratory distress syndromes in neonates born by CD.

Conclusion In our all-comers cohort, replicative of everyday obstetric practice, CD did not improve neonatal outcomes in preterm infants.

Keywords: low birth weight, prematurity, mode of delivery, cesarean delivery

Preterm birth accounts for 12% of all births in the United States.1 Overall, 53% of neonatal deaths occur in births at less than 32 weeks gestation and 68% occur in neonates who weigh less than 2,500 g at birth.2 With an increasing trend for fetal resuscitation at lower birth weights and earlier (often periviable) gestational ages, there is the potential for higher infant and lifelong morbidity and mortality.3 4 5 6 As a result, any effort to reduce the risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality in the most vulnerable of preterm neonates will have an expanded benefit.

It has been suggested by others that low-birth-weight and periviable neonates may lack the reserve necessary to tolerate stress incurred during labor and during the course of a vaginal delivery.7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 While definitive objective evidence for this is lacking, epidemiological studies suggest that cesarean delivery (CD) rate among preterm, low-birth-weight infants continues to rise.15 16 17 This is notable in light of nationwide efforts to decrease the overall CD rate, which currently is estimated at 31%; frequently CD performed at the threshold of viability or among very low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants is low vertical or classical hysterotomy incisions and thus obligates the gravidae to subsequent CD thereafter.18 19 20

Despite these trends toward higher CD rates among low-birth-weight and preterm infants, no consensus has been reached regarding the optimal mode of delivery among those of low birth weight.7 8 9 10 11 12 21 22 23 24 Ideally, one would maximize neonatal benefit while minimizing the maternal morbidity. The significant maternal surgical morbidity sustained with a periviable CD (i.e., classical uterine incision) is not limited to increased blood loss and iatrogenic injury. Importantly, subsequent pregnancies are at an increased risk for uterine rupture, placental abruption, and placenta accreta.18 19 20

While much academic discussion has taken place in the literature regarding the optimal mode of delivery in the premature, low-birth-weight population, the available evidence has not yielded definitive answers. High-grade evidence guiding recommendations for optimal mode of delivery in the preterm infant is limited. A total of six trials have attempted randomization of the mode of delivery but, in total, were only able to recruit 122 subjects. A meta-analysis of four of these trials (116 subjects) did not demonstrate a significant difference in neonatal outcomes and concluded that due to the paucity of subjects recruited, the data are insufficient to draw evidence-based conclusions. All of these trials had significant recruitment problems and, therefore, closed before completion.25 Several observational studies have also been conducted with varying outcomes, most of which were limited by lack of large, population-based cohorts from which to draw their conclusions.7 8 9 10 11 12 13 21 22 23 24 26 27 As a result, the current study aimed to investigate the role of delivery mode, alongside potential confounders, on neonatal outcomes of low-birth-weight neonates in a large, population-based cohort. We hypothesized that mode of delivery would not improve neonatal outcomes in low-birth-weight babies.

Materials and Methods

Study Protocol

In this retrospective cohort study, subject data were obtained following full and informed written subject consent on the PeriBank protocol (institution review board [IRB] H-26364). Additional IRB approval for the current research was obtained under IRB H-33382. Based in Houston, TX, PeriBank is a comprehensive, institutional database and biobank focusing on detailed clinical data and accompanying specimens collected at delivery. Recruitment, specimen processing, storage, and retrieval systems were developed by a multidisciplinary consortium of obstetrician–gynecologists and maternal–fetal medicine specialists, pathologists, nurses, and laboratory staff. All research studies are approved and monitored by a multidisciplinary governance board and the IRB. Subjects were approached on labor and delivery by trained PeriBank research coordinators. At the time of study completion, PeriBank records indicated that 83.5% of all women were approached for enrollment and 95.1% of those were successfully enrolled. As part of the consent process, we discussed with participants the potential risks of participation, including the physical risks associated with specimen collection, and the possibility that protected health information or deidentified project data stored in a public repository could be accidentally released. The protocol and consent form described precautions taken to reduce these risks.

Using our PeriBank database of 6,408 births from a defined interval (August, 2011–February, 2014), we identified all subjects who delivered between 23 weeks 0 day and 36 weeks 6 days (n = 612). We excluded patients who were missing birth weight data (n = 2), who had presented with an intrauterine fetal demise (n = 9), triplet or higher order multiple gestations (n = 2), and those who had lethal or likely fatal fetal anomalies (n = 6). We also excluded any subjects that demised immediately postdelivery as we could not effectively assess neonatal outcomes (n = 1). Finally, we excluded a patient who with monochorionic diamniotic twins who had an interval delivery of twin A at 15 weeks but continued to carry the pregnancy with the remaining twin (n = 1). We deliberately did not exclude twin gestations or breech neonates that were delivered vaginally to attempt to replicate the spectrum and clinical scenarios frequently encountered among deliveries encompassing infants of lower birth weight. This ultimately narrowed our cohort to 591 subjects. We then stratified our cohort by birth weight, dividing our population into the following six groups: < 750, 750 to 999, 1,000 to 1,499, 1,500 to 1,999, 2,000 to 2,499, and ≥ 2,500 g, and later stratified these groups by mode of delivery and neonatal outcomes.

Neonatal outcomes were queried both by individual outcomes and by a composite neonatal outcome score. The neonatal outcome measures included in our composite neonatal outcome were retinopathy of prematurity, necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal death, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), and grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage.28 These findings were abstracted from the participants' medical record. Therefore, the presence or absence of the individual diagnoses used in the composite score was determined according to treating practitioner and not retroactively by study personnel. If the subject was noted to have any of the outcomes in the composite outcome score they were deemed to have the composite outcome. Additionally, the findings were stratified by maternal antenatal steroid exposure.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square analysis and Fisher exact test were used to determine significance between stratified groups. Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of adverse neonatal outcome with each mode of delivery after controlling for parity, gestational age, ethnicity, fetal presentation, and multiple gestations. Additionally, to impute for time (i.e., gestational age achieved) a Cox proportional hazard model was used to calculate hazard ratios with a log-rank test used to quantify p values. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Subject Demographics

Table 1 provides complete demographic information on all enrolled study participants (n = 591). The average age of enrolled subjects was 29.4 years of age, and 74% of participants were multiparous and Hispanic (81%). Multiples comprised 7.8% (n = 46) of our cohort. Additionally, while it should be noted that the overwhelming majority of our study subjects were in cephalic presentation, 11% (n = 65) were breech; 15.4% (10/65) of these breech babies were delivered vaginally. Significant differences in gestational age, race, fetal presentation, and multiple gestations were seen among subjects delivered via CD as compared with vaginal delivery (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics of study cohort.

| Demographics | Overall values | SVD n = 368 |

CD n = 223 |

Significance of difference (p Value for SVD vs. CD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||

| Median age | 30 | 29.2 | 29. 9 | 0.46 |

| Parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | 153/591 (26%) | 91/368 (24.7%) | 62/223 (27.8%) | 0.41 |

| Parous | 438/591 (74%) | 277/368(75.3%) | 161/223 (72.2%) | |

| Gestational age (wk) | ||||

| 23–27 | 26/591 (4.4%) | 12/368 (3.3%) | 14/223 (6.3%) | < 0.001 |

| 28–32 | 89/591 (15.1%) | 38/368 (10.3%) | 51/223 (22.9%) | |

| 33–36 | 476/591 (80.5%) | 318/368(86.4%) | 158/223 (70.9%) | |

| Administration of antenatal steroids (wk) | ||||

| 23–27 | 25/26 (96.2%) | 12/368 (3.3%) | 13/223 (5.8%) | 0.21 |

| 28–32 | 83/89 (93.3%) | 34/368 (9.2%) | 49/223 (21.9%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 14/591 (2.4%) | 8/368 (2.1%) | 6/223 (2.7%) | 0.01 |

| Black | 73/591 (12.4%) | 33/368 (9%) | 40/223 (17.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 485/591 (82.1%) | 315/368 (85.6%) | 170/223 (76.2%) | |

| Asian | 16/591 (2.7%) | 9/368 (2.4%) | 7/223 (3.1%) | |

| Other | 3/591 (0.51%) | 3/368 (0.8%) | 0/223 (0%) | |

| Presentation | ||||

| Cephalic | 496/591 (83.9%) | 342/368 (92.9%) | 154/223 (69.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Breech | 65/591 (11%) | 10/368 (2.7%) | 55/223 (24.7%) | |

| Undocumented | 30/591 (5.1%) | 16/368 (4.3%) | 14/223 (6.3%) | |

| Multiples | ||||

| Twins | 46/591 (7.8%) | 19/368 (5.1%) | 27/223 (12.1%) | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: CD, cesarean delivery; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Note: The majority of our cohort was Hispanic, multiparous, and had a cephalic presentation. Bold values show a significant difference (p < 0.05) between Cesarean delivery and vaginal delivery groups.

Antenatal Corticosteroid Administration

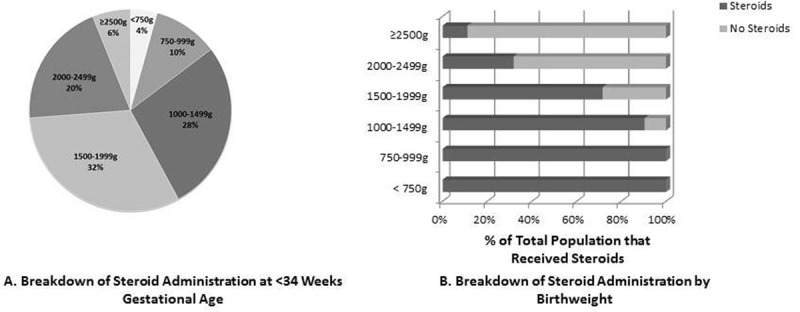

Antenatal corticosteroids were administered to 36.9% of all subjects who delivered between the gestational ages of 23 and 36 weeks gestational age at the time of delivery (n = 218). However, it should be noted that when our cohort was further stratified by gestational age, 96.2% of the women who delivered between 23 and 27 weeks gestational age and 93.3% of subjects who delivered between 28 and 32 weeks gestational age received antenatal corticosteroids. We defined the administration of antenatal corticosteroids to mean that the participant received at least one dose of steroid injection before delivery. When we stratified our cohort into the previously establish birth weight categories, the overwhelming majority of low-birth-weight neonates received at least one dose of antenatal corticosteroids before delivery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration by birth weight and gestational age. Panel A shows the distribution of steroid administration by gestational age. Panel B illustrates steroid distribution by birth weight category. Amongst the low-birth-weight cohort, almost 100% of study participants received at least one dose of antenatal corticosteroids. With increased birth weight and gestational age, this percentage decreased appropriately.

Indications for Delivery

When investigating the mode of delivery and subsequent neonatal outcomes in any population, it is imperative to understand the indication for delivery whether it is maternal or fetal in nature. Understandably, these indications can, themselves, affect neonatal outcomes and prognoses. In our study cohort, delivery indications varied by gestational age. Preterm labor was by far the most common delivery indication in all comers. Preeclampsia and delivery for fetal indications were also commonly noted amongst all groups. When stratified by either gestational age or birth weight, patients with either preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of membranes had a significantly increased likelihood of vaginal delivery. Fetal indications for delivery (such as concerns with fetal heart rate tracings) and/or maternal indications for delivery (such as placental abruption or preeclampsia) more often resulted in CD. As would be anticipated, patients with either a placenta previa or accreta delivered by CD (Table 2).

Table 2. Stratification of gestational age and birth weight by indication for delivery.

| Delivery indication | Gestational age | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 wk 0 d–27 wk 6 d (n = 26) | 28 wk 0 d–32 wk 6 d (n = 89) | 33 wk 0 d–36 wk 6 d (n = 476) | ||||||||||||||||

| Total n (%) | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | Total n (%) | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | Total n (%) | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | |||||||

| Severe preeclampsia | 7 (27%) | 1 (8%) | 6 (43%) | 0.08 | 42 (47%) | 13 (34%) | 29 (57%) | 0.034 | 162 (34%) | 87 (27%) | 75 (48%) | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Placental abruption | 1 (4%) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.46 | 7 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 5 (10%) | 0.694 | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) | 0.04 | ||||||

| PTL/PPROM | 13 (50%) | 9 (75%) | 4 (29%) | 0.047 | 30 (34%) | 22 (58%) | 8 (16%) | < 0.001 | 244 (51%) | 202 (64%) | 42 (27%) | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Fetal indication | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14%) | 0.48 | 11 (12%) | 1 (3%) | 10 (20%) | 0.02 | 53 (11%) | 26 (8%) | 27 (17%) | 0.004 | ||||||

| Chorioamnionitis | 3 (12%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (14%) | 1 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 1 | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 | ||||||

| Previa/accreta | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7%) | 1 | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0.505 | 13 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (8%) | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Birth weight | ||||||||||||||||||

| Delivery indication | < 750 g ( n = 7) | 750–999 g ( n = 17) | 1,000–1,499 g ( n = 52) | 1,500–1,999 g ( n = 88) | 2,000–2,499 g ( n = 176) | ≥ 2,500 g ( n = 251) | ||||||||||||

| SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Value | |

| Severe preeclampsia | 0 (0%) | 2 (67%) | 0.14 | 1 (14%) | 4 (40%) | 0.34 | 10 (42%) | 22 (79%) | 0.01 | 18 (44%) | 27 (57%) | 0.21 | 34 (27%) | 19 (40%) | 0.09 | 38 (23%) | 36 (41%) | 0.003 |

| Placental abruption | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0.41 | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 0.62 | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0.07 | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0.119 |

| PTL/PPROM | 4 (100%) | 1 (33%) | 0.14 | 4 (57%) | 1 (10%) | 0.10 | 11 (46%) | 3 (11%) | 0.01 | 18 (44%) | 9 (19%) | 0.01 | 78 (61%) | 10 (21%) | < 0.001 | 118 (72%) | 30 (35%) | < 0.001 |

| Fetal indication | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – | 0 (0%) | 3 (30%) | 0.23 | 2 (8%) | 4 (14%) | 0.67 | 3 (7%) | 9 (19%) | 0.13 | 14 (11%) | 10 (21%) | 0.09 | 8 (5%) | 13 (15%) | 0.01 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – | 1 (14%) | 2 (20%) | 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 1 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| Previa/accreta | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – | 0 (0%) | 7 (15%) | < 0.001 | 0 (0%) | 7 (8%) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CD, cesarean delivery; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes; PTL, preterm labor; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Note: PTL and PPROM were noted to be the most common indications for preterm delivery. Some patients had more than one indication for delivery (i.e., severe preeclampsia and placental abruption) and in those cases, all indications were included in calculations. Not noted in this table were deliveries for renal disease (n = 1) and deliveries for miscellaneous other indications (n = 6). The p value designates the significance of difference comparing SVD to CD. Bold values show a significant difference (p < 0.05) between cesarean delivery and vaginal delivery groups.

Neonatal Outcomes

As anticipated, lower birth weight categories demonstrated significantly increased occurrence of adverse neonatal outcomes. We observed a statistically significant difference in mode of delivery by birth weight in our institution (chi-square < 0.001). At lower birth weights, CD predominates in our institution (59% in 750–999 g cohort, 54% in 1,000–1,499 g cohort, and 53% in 1,500–1,999 g cohort). The exception is the < 750 g cohort in which 57% were delivered vaginally. In the higher birth weight categories, the trend reverses with a higher predominance of low-birth-weight and preterm infants > 2 kg undergoing vaginal delivery (73% in 2,000–2,499 g cohort, 65% in > 2,500 g cohort).

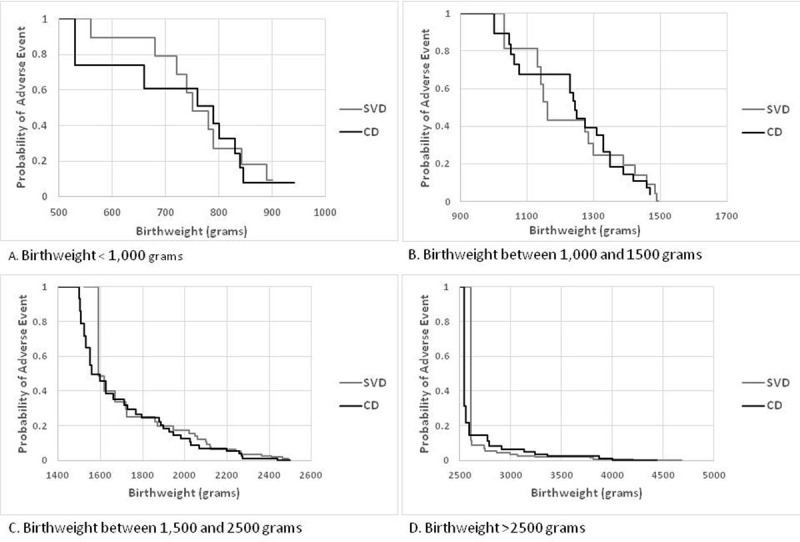

Individually, the neonatal outcomes in question predictably varied by virtue of gestational age (and hence accompanying birth weight). When stratified by birth weight, RDS was significantly more likely with CD in the 1,500 to 1,999 g group (p = 0.003) and approached significance (p = 0.06) in the 1,000 to 1,499 g group (Table 3). However, no other individual outcome significantly varied by birth weight nor gestational age. When examining our composite neonatal outcome by mode of delivery among all birth weight categories, 31.4% (70/223) of infants who delivered via CD experienced complications when compared with 15.5% (57/368) of infants delivered vaginally (p < 0.001, odds ratio [OR]: 2.496, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.67–3.72). Logistic regression was performed to adjust for the effects of gestational age, maternal ethnicity, and parity on neonatal outcomes. The aOR for the adverse neonatal outcome, as determined by our neonatal composite score, was 2.122 with CD (95% CI: 1.28–3.51). However, this significant difference in risk did not persist when the data were modeled with Cox proportional hazard ratios (HR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.6–1.21; log-rank test p = 0.37; Fig. 2). While the trend was toward a protective effect of vaginal delivery, there was no statistically significant difference noted when substratified by birth weight.

Table 3. Stratification of mode of delivery and neonatal outcome by birth weight.

| Birth weight | ROP | NEC | Death | RDS | Composite neonatal outcome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Valuea | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Valuea | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Valuea | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Valuea | SVD n (%) | CD n (%) | p Valuea | |

| < 750 g n = 7 | 1 (14%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (14%) | 1 (14%) | 1 | 1 (14%) | 0 | 1 | 4 (57%) | 2 (29%) | 0.43 | 4 (57%) | 2 (29%) | 0.43 |

| 750–999 g n = 17 | 2 (12%) | 1 (6%) | 0.54 | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 | 5 (29%) | 7 (41%) | 1 | 6 (35%) | 7 (41%) | 0.60 |

| 1,000–1,499 g n = 52 | 5 (10%) | 3 (6%) | 0.45 | 0 | 0 | – | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 | 12 (23%) | 21 (40%) | 0.06 | 13 (25%) | 21 (40%) | 0.12 |

| 1,500–1,999 g n = 88 | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0.47 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0.47 | 7 (8%) | 22 (25%) | 0.003 | 8 (9%) | 22 (25%) | 0.01 |

| 2,000–2,499 g n = 176 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 15 (9%) | 8 (5%) | 0.39 | 15 (9%) | 8 (5%) | 0.39 |

| ≥ 2,500 g n = 251 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 11 (4%) | 10 (4%) | 0.19 | 11 (4%) | 10 (4%) | 0.19 |

Abbreviations: CD, cesarean delivery; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Note: RDS was significantly more likely with CD in the 1,500–1,999 g group (p = 0.003) and contributed to the significant difference in overall composite neonatal outcome with a higher rate among infants delivered via CD. Although grade III intraventricular hemorrhage was included in our composite neonatal outcome, it is not shown in this table because there was only one such case in the entire population (1,000–1,499 g group) and did not contribute to the significant difference. Bold values show a significant difference (p < 0.05) between cesarean delivery and vaginal delivery groups.

p Value denotes significant difference for each outcome among the birth weight strata, comparing SVD to CD.

Fig. 2.

Cox regression model stratified by infant birth weight fails to demonstrate a significant protective benefit to cesarean delivery at any birth weight range. Overall, there was a nonsignificant trend toward a protective effect of vaginal delivery with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.85 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.596–1.212) and a p value of 0.37. Panel A highlights participants with birth weights of < 1,000 g (HR: 1.36, 95% CI: 0.53–3.488, p = 0.52). Panel B shows those with birth weights between 1,000 and 1,500 g (HR: 0.988, 95% CI: 0.486–2.008, p = 0.97). Panel C, again, exhibits no difference in adverse neonatal outcomes by mode of delivery with birth weights between 1,500 and 2,500 g (HR: 1.059, 95% CI: 0.592–1.894, p = 0.85) for vaginal delivery. Finally, in panel D we show participants with birth weights > 2,500 g and no difference in neonatal outcomes by mode of delivery (HR: 0.542, 95% CI: 0.23–1.278, p = 0.17).

Additionally, we looked at neonatal outcomes among women who had a vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC). Overall, 51 women in our study population had a successful VBAC. When stratified by birth weight, no association of VBAC with adverse neonatal outcome was noted in any group except for those in the 2,000 to 2,499 g range. In this population, there was a significant association with VBAC and the adverse outcomes included in our neonatal composite outcome (p = 0.003). Of the 128 spontaneous vaginal deliveries in this birth weight category, 15 experienced adverse neonatal outcomes. Out of the 11 VBACs, 5in this birth weight group had adverse outcomes (45%). Only 10 out of the remaining 117 normal vaginal deliveries (8.5%) had adverse neonatal outcomes.

Finally, given that the majority of neonatal adverse outcomes were associated with RDS, we examined neonatal outcomes in the context of antenatal steroid exposure versus no steroid exposure. When comparing the impact of mode of delivery on neonatal outcomes in this context no differences were seen (p = 0.05; Table 4).

Table 4. Absence of significance of difference in neonatal outcome when controlling for mode of delivery and steroid administration.

| Birth weight | Received antenatal steroids (Adjusted p value) |

Did not receive antenatal steroids (Adjusted p value) |

|---|---|---|

| < 750 g n = 7 |

0.43 | – |

| 750–999 g n = 17 |

0.60 | – |

| 1,000–1,499 g n = 52 |

0.21 | 1 |

| 1,500–1,999 g n = 88 |

0.05 | 1 |

| 2,000–2,499 g n = 176 |

0.12 | 0.45 |

| ≥ 2,500 g n = 251 |

1 | 0.17 |

Note: The significance is approached in the 1,500–1,999 g cohort and this difference in outcome is driven by the increased rate of respiratory distress syndrome noted in the neonates delivered by cesarean delivery within that birth weight category (Table 3).

Discussion

In light of increased capacity and employment of neonatal resuscitation at lower gestational ages and birth weights, the CD rate has continued to increase in this cohort despite a lack of clear evidence of improved neonatal outcomes.14 27 29 30 In examining the trend of obstetrical intervention with an increasing preterm birth rate between 1991 and 2006, MacDorman et al showed a 47% increase in CDs among preterm births during that time frame. The likelihood of CD was inversely proportional to gestational age; 46% of the very preterm infants were born via CD compared with 34.3% of late preterm births.29 Delnord et al investigated CD trends on an international level and found exceedingly high rates amongst very preterm births.31 There are many potential underlying indications for CD in this cohort, such as malpresentation, demonstrated fetal intolerance to labor, maternal indication for immediate delivery, and higher order multiples. However, since it has been suggested by others that there may exist inherent advantage to avoidance of labor in infants of lower birth weight, the increased CD rate may also be a result of perceived benefit relative to risk.13 32

Our study found no improvement in neonatal outcome with CD when subjects were stratified by mode of delivery, both in the presence or absence of antenatal corticosteroid administration. In fact, in the 1,500 to 1,999 g subgroup, there appears to be an increased risk of neonatal morbidity due to the occurrence of neonatal respiratory distress. Among all birth weight categories combined, 31.4% (70/223) of infants delivered via CD experienced complications when compared with 15.5% (57/368) of infants delivered vaginally (p < 0.001, OR: 2.5, 95% CI: 1.67–3.72). This relationship held true even after adjusting for possible confounders between groups with an aOR 2.12 (95% CI: 1.28–3.51). This finding refutes any believed or perceived benefit of CD in low-birth-weight neonates. By attempting to spare low-birth-weight infants from the “stress” of a vaginal delivery, practitioners may, in fact, be subjecting both mother and infant to risk without demonstration of benefit. Interestingly, we did see a positive association between adverse neonatal outcomes and VBACs in one birth weight category. Further studies are necessary to further investigate this finding.

There are several strengths of our study. First, by virtue of a population-based cohort design, it is representative of clinical practice in a large academic center and public care setting and inclusive of varying fetal presentation, singleton and multiple gestations, and precipitous deliveries with failed tocolysis. Second, in addition to gestational age, we were able to stratify our population by birth weight and antenatal steroid exposure. As neonatal resuscitation continues to improve and we continue to amass data on neonatal outcomes in the context of prematurity, we have learned that steroid exposure and birth weight are key determinants, without which our prognostic abilities are severely limited. Third, we were also able to replicate a typical clinical population by including breech deliveries and twin gestations. Finally, by utilizing a comprehensive institutional database from a large volume academic center, we were able to capture considerable and contemporary information. This ensures that our data are reflective of current practice patterns and not confounded with changes in medical standard of care over time (notably neonatal care), as might be the case in other longitudinal or multi-institutional studies.

Our study is not without limitations. The retrospective nature of our study is similarly a limitation. Due to its retrospective design, we were unable to sort subjects by “intent to treat.” Therefore, participants were analyzed by their ultimate mode of delivery rather than by the intended mode of delivery. While some might be concerned about the potential bias that such classification might impart, it is prudent to note that no significant differences in rates of RDS were noted by fetal indication for CD. Additionally, despite a robust clinical cohort in an at-risk population, only a small number of neonates had adverse outcomes. This is, however, reflective of the clinical reality in our institution and many other level III and level IV neonatal intensive care units. Finally, our model treated twins as independent beings and was unable to account for the interplay between the individuals on fetal outcomes. However, multiples constitute a minority of our sample size (7.8% of the total population) and were included to ensure a comprehensive cohort.

Finally, it is important to note that given the nature of our patient population, our study cohort is largely Hispanic. While this may make our study generalizable to many parts of the United States, caution should be taken before applying these statistics to all women. We did, of note, compute a post hoc power calculation. To achieve 80% power with an α of 0.05, we would have needed 111 participants in each mode of the delivery cohort. Indeed, our study population allowed us to achieve 98% power.

In addition, we could not, encode for all potential indications for the mode of delivery and conceivable confounders and thus cannot assume that a cesarean-delivered infant would have had the same low-morbid outcome had they delivered vaginally. However, by interrogating all-comers in a population-based cohort, we can state that there is no realized inherent benefit to CD, potential harm may exist with this route of delivery in certain low-birth-weight babies, and we would thus support a policy of reserving CD for indications beyond gestational age or VLBW.

In sum, we acknowledge that premature, low-birth-weight deliveries present a uniquely challenging clinical situation. In trying to optimize neonatal outcomes by erring toward CD, we fail to observe improved neonatal outcomes and, in fact, note an increased neonatal morbidity in certain subgroups. We thus have potentially subjected gravidae to the surgical morbidity of CD without clear and evident neonatal benefit. In sum, in an adequately powered, single institutional, population-based cohort, we have failed to observe neonatal benefit to CD when stratified by birth weight or gestational age when accounting for antenatal steroid administration.

Funding

The effort for this study was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant no. R01NR014792, K. M. A), the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Initiative (K. M. A.), and the Center for Translational Environmental Health Research (Grant no. P30ES023512, M. B.).

Author Contributions D. R. wrote the article. D. R. and K. A. extracted and analyzed the data. J. H. assisted with data extraction. K. M. A. guided experimental design and researched data, reviewed/edited the article, and contributed to the discussion. Conflict of Interest The authors report no conflict of interest.

Note

This article was presented as a poster at the 34th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine; February 3–8, 2014, New Orleans, LA (abstract 662). The second portion of our work has been accepted for presentation as a poster at the 36th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine; February 1–6, 2016, Atlanta, GA (abstract # 842).

References

- 1.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Practice bulletin no. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964–973. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews T J, MacDorman M F. Infant mortality statistics from the 2010 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(8):1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoelhorst G MSJ, Rijken M, Martens S E. et al. Changes in neonatology: comparison of two cohorts of very preterm infants (gestational age <32 weeks): the Project On Preterm and Small for Gestational Age Infants 1983 and the Leiden Follow-Up Project on Prematurity 1996-1997. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):396–405. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soleimani F, Zaheri F, Abdi F. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after preterm birth. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(6):e17965. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.17965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper R G, Rehman K U, Sia C. et al. Neonatal outcome of infants born at 500 to 800 grams from 1990 through 1998 in a tertiary care center. J Perinatol. 2002;22(7):555–562. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlapbach L J, Adams M, Proietti E. et al. Outcome at two years of age in a Swiss national cohort of extremely preterm infants born between 2000 and 2008. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(1):198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H C, Gould J B. Survival advantage associated with cesarean delivery in very low birth weight vertex neonates. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):97–105. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000192400.31757.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H C, Gould J B. Survival rates and mode of delivery for vertex preterm neonates according to small- or appropriate-for-gestational-age status. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1836–e1844. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deulofeut R, Sola A, Lee B, Buchter S, Rahman M, Rogido M. The impact of vaginal delivery in premature infants weighing less than 1,251 grams. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(3):525–531. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154156.51578.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankaran S, Fanaroff A A, Wright L L. et al. Risk factors for early death among extremely low-birth-weight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):796–802. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westgren M, Dolfin T, Halperin M. et al. Mode of delivery in the low birth weight fetus. Delivery by cesarean section independent of fetal lie versus vaginal delivery in vertex presentation. A study with long-term follow-up. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1985;64(1):51–57. doi: 10.3109/00016348509154688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonas H A, Khalid N, Schwartz S M. The relationship between Caesarean section and neonatal mortality in very-low-birthweight infants born in Washington State, USA. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1999;13(2):170–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malloy M H. Impact of cesarean section on neonatal mortality rates among very preterm infants in the United States, 2000-2003. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):285–292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer B M. Mode of delivery for periviable birth. Semin Perinatol. 2013;37(6):417–421. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lumley J. Method of delivery for the preterm infant. BJOG. 2003;110 20:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer M S, Platt R, Yang H. et al. Secular trends in preterm birth: a hospital-based cohort study. JAMA. 1998;280(21):1849–1854. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horbar J D, Badger G J, Carpenter J H. et al. Trends in mortality and morbidity for very low birth weight infants, 1991-1999. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):143–151. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 Pt 1):450–463. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osmundson S S, Garabedian M J, Lyell D J. Risk factors for classical hysterotomy by gestational age. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):845–850. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a39731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakhshi T, Landon M B, Lai Y. et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of repeat cesarean delivery in women with a prior classical versus low transverse uterine incision. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27(10):791–796. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riskin A Riskin-Mashiah S Lusky A Reichman B; Israel Neonatal Network. The relationship between delivery mode and mortality in very low birthweight singleton vertex-presenting infants BJOG 2004111121365–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato E H, Yamada H, Matsumoto Y, Hattori S, Makinoda S, Fujimoto S. Relation between perinatal factors and outcome of very low birth weight infants. J Perinat Med. 1996;24(6):677–686. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1996.24.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melchor J C, Aranguren G, López J A, Avila M, Fernández-Llebrez L, Linares A. Perinatal outcome of very low birthweight infants by mode of delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1992;38(3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(82)90126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muhuri P K, Macdorman M F, Menacker F. Method of delivery and neonatal mortality among very low birth weight infants in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(1):47–53. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0029-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alfirevic Z, Milan S J, Livio S. Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preterm birth in singletons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD000078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000078.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wylie B J Davidson L L Batra M Reed S D Method of delivery and neonatal outcome in very low-birthweight vertex-presenting fetuses Am J Obstet Gynecol 200819866400–6.4E9., discussion e1–e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy U M, Zhang J, Sun L, Chen Z, Raju T NK, Laughon S K. Neonatal mortality by attempted route of delivery in early preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):1170–1.17E10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercer B M, Rabello Y A, Thurnau G R. et al. The NICHD-MFMU antibiotic treatment of preterm PROM study: impact of initial amniotic fluid volume on pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2):438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacDorman M F, Declercq E, Zhang J. Obstetrical intervention and the singleton preterm birth rate in the United States from 1991-2006. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2241–2247. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Högberg U, Holmgren P A. Infant mortality of very preterm infants by mode of delivery, institutional policies and maternal diagnosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(6):693–700. doi: 10.1080/00016340701371306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delnord M, Blondel B, Drewniak N. et al. Varying gestational age patterns in cesarean delivery: an international comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:321. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bottoms S F, Paul R H, Iams J D. et al. Obstetric determinants of neonatal survival: influence of willingness to perform cesarean delivery on survival of extremely low-birth-weight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(5):960–966. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]