Abstract

Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) protein is a member of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, which is also known as FGF-7. The FGF-7 plays an important role in tumor angiogenesis. In the present work, FGF-7 is treated as a potential therapeutic target to prevent angiogenesis in cancerous tissue. Computational techniques are applied to evaluate and validate the 3D structure of FGF-7 protein. The active site region of the FGF-7 protein is identified based on hydrophobicity calculations using CASTp and Q-site Finder active site prediction tools. The protein–protein docking study of FGF-7 with its natural receptor FGFR2b is carried out to confirm the active site region in FGF-7. The amino acid residues Asp34, Arg67, Glu116, and Thr194 in FGF-7 interact with the receptor protein (FGFR2b). A grid is generated at the active site region of FGF-7 using Glide module of Schrödinger suite. Subsequently, a virtual screening study is carried out at the active site using small molecular structural databases to identify the ligand molecules. The binding interactions of the ligand molecules, with piperazine moiety as a pharmacophore, are observed at Arg67 and Glu149 residues of the FGF-7 protein. The identified ligand molecules against the FGF-7 protein show permissible pharmacokinetic properties (ADME). The ligand molecules with good docking scores and satisfactory pharmacokinetic properties are prioritized and identified as novel ligands for the FGF-7 protein in cancer therapy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12154-016-0152-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ADME, Angiogenesis, FGF-7, Protein–protein docking, Virtual screening

Introduction

Angiogenesis is a physiological process, which is essential for the growth of new vasculature in the cells and plays an important role in tumor progression and metastasis [1–3]. The formation of new blood vessels is regulated by several signaling molecules like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF is regulated by fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), which induce epithelial cells to synthesize and release the VEGFs. The VEGFs are important for endothelial cell migration and cell proliferation and for promoting angiogenesis. The negative regulation of VEGF can be achieved by inhibiting the overexpression of FGF proteins and thereby inhibiting the angiogenesis in cancer cells [4–6].

FGFs are expressed in all tissues and play a major role in wound healing and tumorigenesis [7, 8]. FGF-7 is a member of the FGF family, also known as keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) and is overexpressed in tumor tissue [9]. FGF-7 is a paracrine growth factor, which is produced by the mesenchymal cells and acts on epithelial cells [10]. FGF-7 is one of the highly expressed proteins in keratinocytes [11] and is a mitogenic factor expressed in epithelial tissues [12, 13]. The oncogenic role of the FGF protein is evident from the increased mobilization in cancer cells [14–16]. The FGF-7 signaling is initiated by complex formation with its natural receptor, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2-IIIb (FGFR2b) [17–19].

FGF signaling through FGFR2b leads to the activation of multiple signal transduction pathways. The FGFR2b is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), expressed in epithelial cells, which stimulates cell migration, proliferation, survival, and differentiation. It has a vital role in cancer progression [20, 21]. Binding of FGF-7 with its receptor leads to the activation of cell proliferation pathways. Phosphorylated tyrosine residues of RTKs act as docking sites to a variety of adaptor proteins, which result in activation of multiple signaling pathways like RAS, RAF, MAPK, PI3K, AKT, STAT, and PLCγ. At present, several FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are in clinical trials. These TKIs are reported to have severe side effects [22]. Hence, targeting FGFRs may result in impairment of associated functions in multiple pathways. The recent studies explore the importance of FGFs in angiogenesis, hence FGFs are targeted for cancer therapy [23].

FGF proteins are promising targets for the management of side effects associated with the cancer therapy. A few of the examples are (1) side effects of chemotherapies and radiotherapies [24], (2) T cell deficiency [25], and (3) testicular toxicity [26]. The above discussed scientific reports suggest that the active engagement of the FGF-7 protein can be a promising drug target. The FGF-7 protein binds to its natural receptor FGFR2b that leads to angiogenesis, which in turn helps in supply of nutrients and oxygen to tumor formation [27]. The therapeutic approach for cancer, targeting the intermolecular interaction site between FGF-7 and FGFR2b, is a novel drug discovery strategy [28, 29]. In the present study, the FGF-7 protein is considered as a novel target for the identification of new molecular entities against angiogenesis [30].

Methodology

Homology modeling of the FGF-7 protein

Comparative modeling techniques are widely used by computational chemists to predict the three-dimensional (3D) models of proteins [31, 32]. The 3D structure of the protein is essential to know the biochemistry of the protein. In the absence of the crystal structure of the FGF-7 protein, comparative modeling methods are applied to build the 3D structure of the FGF-7 protein.

The amino acid sequence of the target protein is retrieved in FASTA format from the ExPASy Swiss-Prot (Expert protein analysis system) server (http://www.expasy.org) [33]. The template selection is carried out using template search tools such as Position-Specific Iterative Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (PSI-BLAST) [34, 35] for sequence, Jpred3 for Secondary structure [36], and Protein Homology/analogy Recognition Engine (PHYRE) for fold similarities [37], respectively. Proteins with the lowest e-values are considered as templates, based on the sequence identity and the statistical measures. The multiple sequence alignment of the target protein, with the sequences of selected templates, is carried out with ClustalW tool [38].

MODELLER program is used for comparative modeling of 3D structures of proteins [39]. The target protein and template sequences and the 3D coordinates of the template protein are submitted to MODELLER9v7 program to generate the homology model of the target protein. The 3D model of the protein with the lowest MODELLER objective function is selected for further studies [40]. Loop building is carried out for the amino acids with low stereochemical quality in the 3D model of the target protein using build loop module in Swiss-PDB Viewer (SPDBV), which calculates bad contacts, clashes, and hydrogen bonds. The protein structures are visualized and analyzed with SPDBV, which is an interactive molecular graphics program [41, 42].

Validation of FGF-7 protein 3D model

The refinement of the initial model of the target protein is followed by energy minimization. The 3D model of the FGF-7 protein is prepared using the protein preparation wizard of Schrödinger 9.0.1 (Schrödinger, LLC, 2008, New York, NY). In the protein preparation, bond orders are assigned, hydrogens added, and unwanted water molecules removed from the protein. Energy minimization is carried out using Impref module of Schrödinger suite with the default cutoff root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of 0.3 Å using Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations (OPLS) 2005 force field. The model is validated by PROCHECK [43, 44] from the Structural Analysis and Verification Server (SAVES). The stereochemical quality of the resulting protein 3D model is interpreted with Ramachandran plot [45] by checking the dihedral angles phi and psi of the amino acid residues. The local model quality is assessed by ProSA server [46].

Active site prediction

The active site of the protein is a unique binding site of the protein that is responsible for a specific function. Identification of a binding site is an important step in structure-based drug design. The active site region of the FGF-7 protein is identified by using Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of Proteins (CASTp) [47] and Q-Site Finder [48] server tools. CASTp and Q-site Finder servers measure systematically the area and volume of each cavity to assess the active site domain.

Protein–protein docking

Protein–protein (P-P) docking is carried out between FGF-7 and its receptor FGFR2b with the help of ZDOCK 3.0.1 [49] software to identify the specific binding residues within the binding domain of the FGF-7 protein. The energy-minimized structures of the target protein and its receptor protein are docked using ZDOCK 3.0.1 program to study their binding interactions. The site-specific docking is carried out using block.pl, by blocking the active site domain residues in FGF-7, which are identified from the CASTp and Q-site Finder, for considering the active site of FGF-7. Different docked poses are created using create.pl; 200 docked complexes are generated and ranked using the z-score. The top ranking docked complexes are re-ranked according to the energy-based potential, calculated using the pairwise shape complementarity algorithm employed in Z-rank [50].

Grid generation

The energy-minimized protein structure is considered for the grid generation at the active site region. A grid with the size of 80 Å × 80 Å × 80 Å, centered on the centroid within the box, is generated using the Grid-based Ligand Docking with Energetics (Glide) software, at the active site domain residues. The box encloses the entire groove near the active site to fit the ligands [51, 52].

Virtual screening

The energy-minimized 3D structure of the protein is taken for virtual screening, to identify novel ligand molecules for binding at the active site of the protein [53]. Virtual screening studies are carried out at the active site using virtual screening work flow of Glide in Schrödinger suite [54]. The docking module of Glide software uses Monte Carlo-based simulations.

Ligand preparation

The ligand molecules from different small molecular databases are retrieved in structure data file (SDF) format. The molecules are subjected to ligand preparation using LigPrep module of Schrödinger suite (Schrödinger 2010) [55]. The ligand preparation process of molecules involves preserving the definite chiralities, to generate minimum five low-energy stereoisomers per ligand, using default conditions at pH 7.0 ± 2.0. The resulting ligands are subjected to virtual screening using the Glide module of Schrödinger suite.

Docking

Glide is a docking program that uses a series of filters to identify the protein binding site residues for acceptable ligand poses [54]. Virtual screening workflow is used to screen several data bases. High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) mode is used for screening of structural databases with high accuracy, followed by the standard precision (SP) mode for specific docking and later extra precision (XP) mode, for the elimination of false positives to filter ligands with high affinity towards the FGF-7 protein. The ligands are docked flexibly in the Glide module with HTVS/SP/XP modes, by retaining 10 % of the ligands with the best glide score in each step, using the OPLS-2005 force field [56]. The docked ligand molecules are prioritized based on the glide score and glide energy. Similar protocols were reported earlier by Vasavi et al. and Durrant JD et al., in the identification of new ligand molecules [57, 58].

Solvent accessible surface area

The solvent accessible surface area (SASA) values of the FGF-7 protein and ligand molecules, before and after docking, are analyzed, setting a probe radius value at 1.40 Å and 240 grid points per atom. The SASA is calculated for the FGF-7 protein using Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer (Accelrys Software Inc., Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer v 3.5., San Diego: Accelrys Software Inc., 2012).

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination

The ligands identified in the XP docking mode are subjected to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination (ADME) prediction. The pharmacokinetic properties are evaluated using QikProp module of the Schrödinger suite [59].

Results and discussion

Structural evaluation of the FGF-7 protein

The 3D structure of the FGF-7 protein is not reported so far in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The 3D model of the FGF-7 protein was generated using homology modeling techniques, based on its sequence similarity with proteins of known structure, which were used as templates. The retrieved amino acid sequence of the FGF-7 protein was subjected to BLAST, Jpred3, and PHYRE search, against the PDB, to identify suitable template structures for comparative modeling. Proteins with PDB IDs, 1QQK_A and 3ICJ, were selected as suitable templates, based on lowest “e” values (Supplementary Table 1). The template proteins for FGF-7 were identified based on the sequence similarity scores obtained from different servers. The FGF-7 (human) protein has a chain length of 194 amino acid residues. 1QQK_A (rat) has a 194-amino acid chain length, but the crystal structure availability is for 132 amino acid residues only. The query coverage of the FGF-7 (human) protein with the template 1QQK_A (rat) is 72 %. Hence, a multiple alignment is carried out using 1QQK_A and 3ICJ as templates.

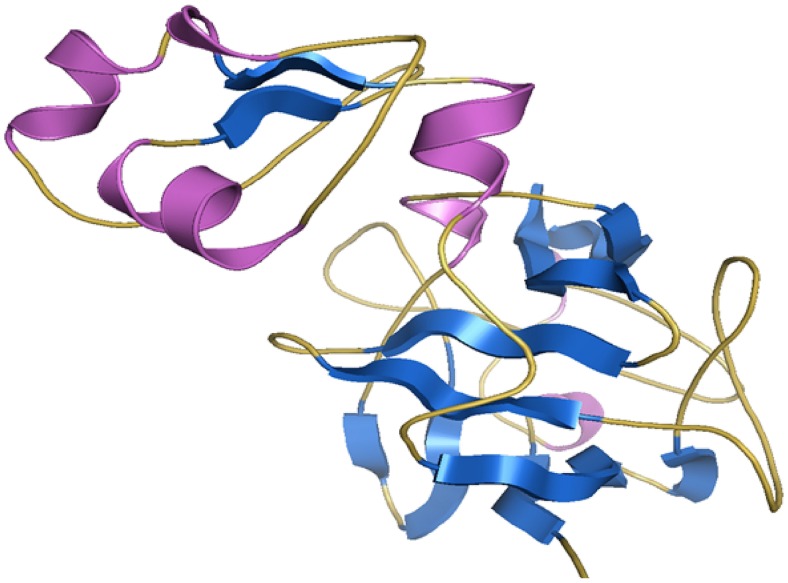

Multiple alignment between the target protein FGF-7 and the templates 1QQK_A and 3ICJ was carried out using ClustalW (Supplementary Fig 1). The 3D model of the target protein was generated using MODELLER 9v7 program. Twenty-five models were generated, out of which the model with the lowest MODELLER objective function was selected (Fig. 1) for further refinement by loop building, in Swiss-PDB Viewer.

Fig. 1.

Homology model of FGF-7 protein. The FGF-7 homology model represented as cartoon. Helices are represented in pink, sheets in blue, and loops in yellow orange color as generated by the PyMOL program

Validation of FGF-7 protein structure

The stereochemical quality of the generated 3D model of the FGF-7 protein was validated using PROCHECK. The Ramachandran plot (Supplementary Fig 2) statistics shows 143 out of a total of 194 amino acid residues in the most favored region, 31 residues in the additionally allowed region, one residue in the generously allowed region, and none in the disallowed region. Of the amino acid residues, 99.4 % are in the energetically favorable region, which implies a good stereochemical quality of the protein structure. ProSA calculates the fold quality and deviation in the total energy of the structure with respect to the energy distribution in terms of z-score. The ProSA plot gives the local quality of the model and energy (Supplementary Fig 3a) as a function of amino acid sequence position. The overall energy profile of the FGF-7 model as given by the z-score is −2.24 (Supplementary Fig 3b), which is in the range of the value of that for the existing crystallographic structures determined by either X-ray or NMR.

Active site prediction

The conserved domains of the FGF-7 protein, which also include the site of receptor interaction, are in the amino acid range of 67 to 192 (Supplementary Fig 4). Active site residues and their corresponding cavity volumes were predicted for FGF-7, based on the hydrophobic pocket evaluation with the CASTp and Q-site Finder servers. The Q-site Finder server assesses the energetically favorable binding sites of the FGF-7 protein using a van der Waals probe of radius 1.4 Å [48]. Binding pocket search results from the CASTp and Q-site Finder servers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Similar protocols were reported earlier by Malkhed et al., Ramatenki et al., and Sing et al. for the identification of the active site domain [60–62].

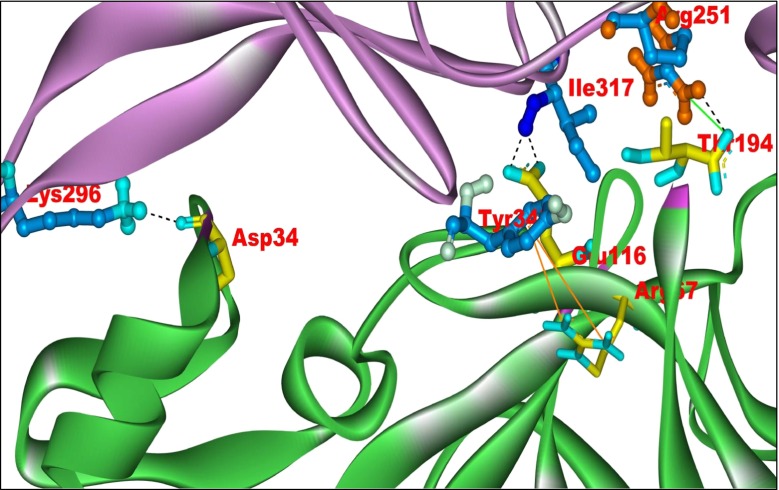

The protein–protein docking between the FGF-7 and FGFR2b proteins was carried out using ZDOCK 3.0.1 program. An output of 200 docked complexes were generated and ranked based on their z-score. The top ranking docked complexes were re-ranked using Z-rank. The docked complex with the best Z-rank was prioritized (energy value −71.60 kcal/mol) and analyzed, by manual inspection using the Discovery Studio Visualizer, for H-bonds, pi-cation, and salt bridge interactions (Supplementary Table 3). The docked complex shows four hydrogen bonds, one salt bridge, and two pi-cation interactions (Fig. 2). The residues of FGF-7, namely, Thr194, Asp34, Glu116, and Arg67, bind to Arg251, Lys296, Ile317, and Tyr345 of FGFR2b, respectively. It may be inferred from the results obtained from the active site prediction tools that the FGF-7 residues Thr194, Asp34, Glu116, and Arg67 are important for angiogenesis processes in cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

The binding interactions of FGF7–FGFR2b docked complex. The best docked complex from the protein–protein docking studies, prioritized on the basis of Z-rank, is presented, out of an output of 200 docked complexes. FGFR2b is represented in purple solid ribbon and FGF-7 in green. Four hydrogen bonds are shown in black dotted lines, one salt bridge in light green line, and two pi-cation interactions in orange lines

Virtual screening and ADME analysis

Virtual screening studies were carried out using various chemical databases against the FGF-7 protein. Ten thousand molecules from CB NovaCare and 10,000 molecules from Sigma-TimTec, both subsets of ChemMine Database [63], were retrieved. A total of 37,071 ligand structures were generated from the ligand preparation of the CB NovaCare structural databank. The generated conformers were screened hierarchically, in HTVS, SP, and XP modes, with an output of default 10 % at each stage. One hundred eighty docked complexes were generated with the CB NovaCare ligand database.

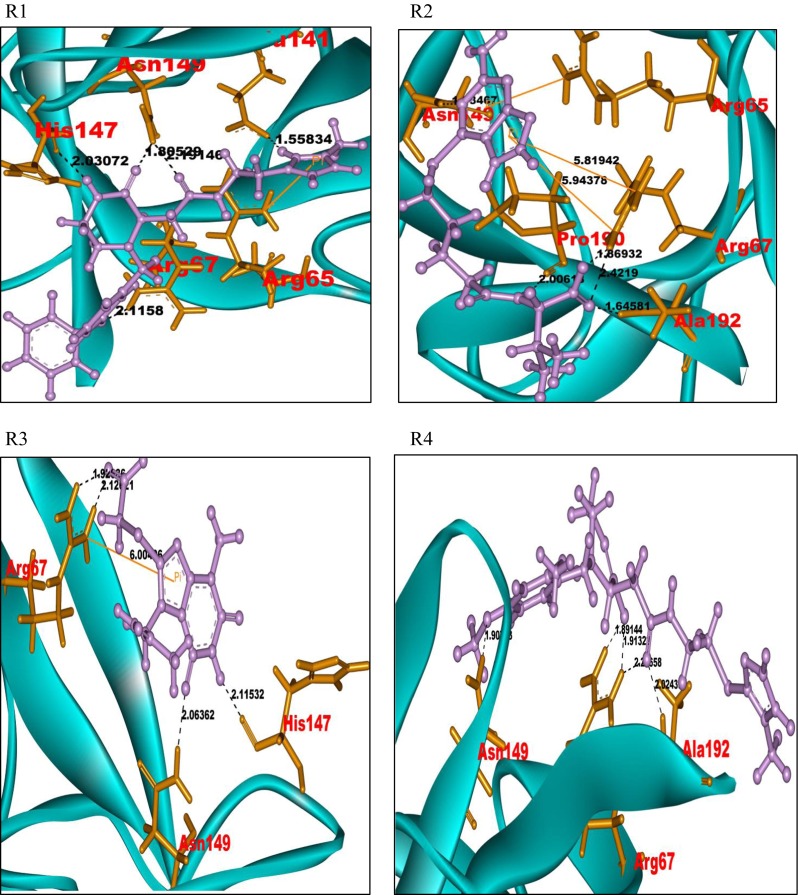

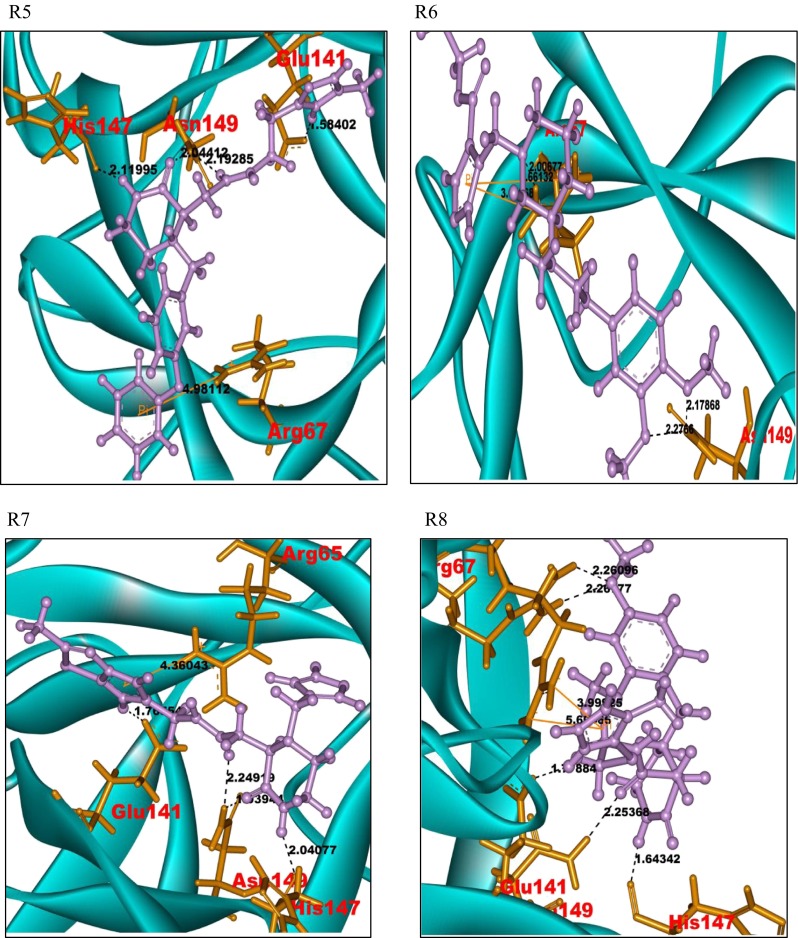

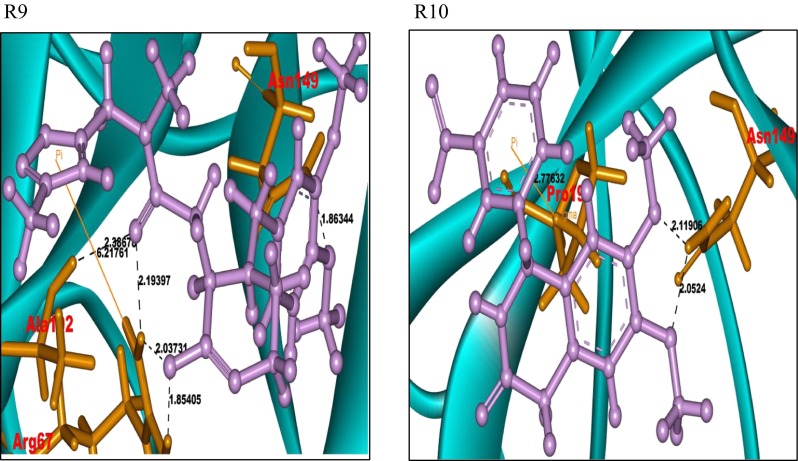

A similar protocol was followed with the Sigma-TimTec structural databank. In the ligand preparation process, 17,673 structures were generated. Further virtual screening through HTVS, SP, and XP modes gave an output of five docked structures. These ligands were considered for the identification of potent ligand molecules as drug candidates of the FGF-7 protein. A total of 185 docked complexes, generated, show a Glide score in the range of −8.03 to −6.05. Pictures of the docked complexes of the ligands R1 to R10 with the protein FGF-7 are presented in Fig. 3. A sample of 14 docked ligand molecules were prioritized based on the Glide score and Glide energy. The data along with the intermolecular interactions in the ligand–FGF-7 docked complexes are represented in Supplementary Table 4. The ligand molecules numbered R1 to R14 have hydrogen bonds and pi-cation interactions with the amino acid residues, Arg65, Arg67, Glu141, His147, Asn149, Pro190, and Ala192, of the FGF-7 protein. The ligand molecules R1, R4, R5, R7, R8, R9, R12, and R13 respectively have a common substituted piperazine acetamide pharmacophore moiety. The Piperazine pharmacophore, present in all the said ligand molecules, shows selective and specific binding affinity towards the amino acid residues Arg67 and Asn149 of the FGF-7 protein.

Fig. 3.

Docked pictures of ligands R1–R10 with protein FGF-7 showing bonding interactions. Binding interactions of the FGF-7 protein with its ligands. The protein is represented in cyan solid ribbon form. The FGF-7 protein amino acid residues are represented in orange sticks, ligands in purple ball and stick form. The hydrogen bond interactions are represented in black. The pi-cation interactions are represented in yellow

The ligand molecules R2, R3, R6, R10, R11, and R14 also show similar binding interactions towards the residues Arg67 and Asn149 of the FGF-7 protein. All the ligands that bind at the active site of the FGF-7 protein exhibit piperazine-like binding ability.

The SASA values of the docked FGF-7 protein–ligand complexes were compared with that of the free FGF-7 protein. The SASA values (Supplementary Fig 5) of the residues which are involved in the binding with the ligands show a decrease in SASA values after docking. The present study suggests that the amino acid residues Arg65, Arg67, Glu141, His147, Asn149, Pro190, and Ala192 are important for binding with ligands.

A major cause of failure of the new lead development in drug discovery process is the lack of prior information about ADME. Hence, an in silico prediction of ADME properties is taken up to improve the success rate of drug candidates to reach further stages of the development [64].

The predicted ADME properties for the ligands are shown in Table 1. The 14 ligand molecules (R1–R14) have central nervous system (CNS) values ranging from −2 to 1, donor hydrogen bonds from 1 to 4.25, acceptor hydrogen bonds ranging 6 to 10, QPlogP of n-octanol/water values ranging from −0.08 to 3.06, and the molecular weight below 450, all of which represent properties within the acceptable range. The molecules also obey the Lipinski rule of five [65] and Jorgensen rule of three [66], which show that they have drug-like properties and can be projected to be new molecules that can inhibit the FGF-7 protein activity towards angiogenesis in cancer cells. The ligand molecules within the permissible range of ADME properties may be considered as novel antagonists for the FGF-7 protein.

Table 1.

ADME or pharmacokinetic predictions of the top 14 docked molecules of ChemMine Database library prioritized with high Glide score using Qikprop

| Molecule | Stars | CNS | DHB | AHB | Qplog | Qplog | % HOA | ROF | ROT | Mol wt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Po/w | BB | |||||||||

| R1 | 0 | −2 | 3 | 9 | 2.02 | −1.25 | 68.55 | 0 | 0 | 447.54 |

| R2 | 0 | −2 | 4.25 | 7.75 | 1.19 | −2.33 | 50.45 | 0 | 1 | 366.43 |

| R3 | 0 | −2 | 2 | 7 | 1.41 | −1.29 | 62.67 | 0 | 0 | 310.32 |

| R4 | 0 | −1 | 2 | 8.5 | 1.55 | −0.95 | 62.85 | 0 | 0 | 447.55 |

| R5 | 0 | −2 | 3 | 9 | 1.98 | −1.19 | 68.41 | 0 | 0 | 447.54 |

| R6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 | 3.06 | −0.49 | 76.06 | 0 | 0 | 430.55 |

| R7 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 | −0.08 | −0.68 | 56.80 | 0 | 1 | 388.44 |

| R8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1.40 | −0.68 | 71.26 | 0 | 0 | 447.55 |

| R9 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 9 | 0.59 | −0.96 | 54.58 | 0 | 2 | 416.47 |

| R10 | 0 | −2 | 1 | 7 | 1.7 | −1.13 | 73.79 | 0 | 0 | 328.32 |

| R11 | 0 | −2 | 2 | 8.7 | 0.90 | −1.61 | 58.36 | 0 | 0 | 328.34 |

| R12 | 1 | −2 | 3 | 9.5 | −0.02 | −1.09 | 56.01 | 0 | 1 | 371.44 |

| R13 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 9 | −0.32 | −0.95 | 51.39 | 0 | 2 | 416.48 |

| R14 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2.89 | −0.48 | 85.60 | 0 | 0 | 341.39 |

The permissible ranges are as follows: central nervous system (CNS) −2(inactive) +2(active); hydrogen bond donors (DHB) (0.0–6.0); hydrogen bond acceptors (AHB) (2.0–20.0); octanol/water partition coefficient (QPlogPo/w) (−2.0–6.5); brain–blood barrier partition coefficient (QPlogBB) (−3.0–1.2); percentage human oral absorption (% HOA) >80 % high, <25 % low; rule of five (ROF) 4; rule of three (ROT) 3; molecular weight (Mol wt) 130–725

Conclusion

The 3D structure of the FGF-7 protein was evaluated by homology modeling technique and validated by standard protocols. Protein–protein docking studies reveal that the residues Asp34, Arg67, Glu116, and Thr194 of FGF-7 facilitate binding to its natural receptor FGFR2b. Virtual screening results have shown a common substituted piperazine-like pharmacophore to be important for effective binding to FGF-7. All the ligands exhibit similar interactions with Arg-67 and Asn149 of the FGF-7 protein. The above study projects several new ligands that have the piperazine pharmacophore moiety, which is important for designing new leads as competitive inhibitors of FGF7 against the FGFR2b protein.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 245 kb)

(GIF 14 kb)

(GIF 15 kb)

(GIF 18 kb)

(GIF 16 kb)

(GIF 11 kb)

(GIF 11 kb)

Acknowledgments

R.V. acknowledges the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)-INDIA for financial support. The authors R.K.D. and S.P.V. acknowledge the UGC-INDIA for financial support. The author V.R. acknowledges the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)-INDIA for financial support. The authors R.V., K.K.M., N.N., R.D., R.K.D., V.R., and S.P.V. acknowledge the Principal and the Head Department of Chemistry, University College of Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad, for providing facilities to carry out the work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finch PW, Rubin JS. Keratinocyte growth factor expression and activity in cancer: implications for use in patients with solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:812–824. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrara N, Gerber H-P, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coultas L, Chawengsaksophak K, Rossant J. Endothelial cells and VEGF in vascular development. Nature. 2005;438:937–945. doi: 10.1038/nature04479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:549–580. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laestander C, Engström W. Role of fibroblast growth factors in elicitation of cell responses. Cell Prolif. 2014;47:3–11. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–364. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuboi R, Sato C, Kurita Y, Ron D, Rubin JS, Ogawa H. Keratinocyte growth factor (FGF-7) stimulates migration and plasminogen activator activity of normal human keratinocytes. J Investig Dermatol. 1993;101:49–53. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12358892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillis P, Savla U, Volpert OV, Jimenez B, Waters CM, Panos RJ, Bouck NP. Keratinocyte growth factor induces angiogenesis and protects endothelial barrier function. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2049–2057. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.12.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beer HD, Gassmann MG, Munz B, Steiling H, Engelhardt F, Bleuel K, Werner S. Expression and function of keratinocyte growth factor and activin in skin morphogenesis and cutaneous wound repair. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2000;5:34–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamayoshi T, Nagayasu T, Matsumoto K, Abo T, Hishikawa Y, Koji T. Expression of keratinocyte growth factor/fibroblast growth factor-7 and its receptor in human lung cancer: correlation with tumour proliferative activity and patient prognosis. J Pathol. 2004;204:110–118. doi: 10.1002/path.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin JS, Osada H, Finch PW, Taylor WG, Rudikoff S, Aaronson SA. Purification and characterization of a newly identified growth factor specific for epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:802–806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.3.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birrer MJ, Johnson ME, Hao K, Wong KK, Park DC, Bell A, Welch WR, Berkowitz RS, Mok SC. Whole genome oligonucleotide-based array comparative genomic hybridization analysis identified fibroblast growth factor 1 as a prognostic marker for advanced-stage serous ovarian adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2281–2287. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricol D, Cappellen D, El Marjou A, Gil-Diez-de-Medina S, Girault JM, Yoshida T, Ferry G, Tucker G, Poupon MF, Chopin D, Thiery JP, Radvanyi F. Tumour suppressive properties of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2-IIIb in human bladder cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:7234–7243. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Wang H, Toratani S, Sato JD, Kan M, McKeehan WL, Okamoto T. Growth inhibition by keratinocyte growth factor receptor of human salivary adenocarcinoma cells through induction of differentiation and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11336–11340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191377098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maretzky T, Evers A, Zhou W, Swendeman SL, Wong PM, Rafii S, Reiss K, Blobel CP. Migration of growth factor-stimulated epithelial and endothelial cells depends on EGFR trans activation by ADAM17. Nat Commun. 2011;2:229. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansal GS, Cox HC, Marsh S, Gomm JJ, Yiangou C, Luqmani Y, Coombes RC, Johnston CL. Expression of keratinocyte growth factor and its receptor in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1567–1574. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ornitz DM, Marie PJ. FGF signaling pathways in endochondral and intramembranous bone development and human genetic disease. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1446–1465. doi: 10.1101/gad.990702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:116–129. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cross MJ, Claesson-Welsh L. FGF and VEGF function in angiogenesis: signalling pathways, biological responses and therapeutic inhibition. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:201–207. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01676-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad I, Iwata T, Leung HY. Mechanisms of FGFR-mediated carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:850–860. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finch PW, Yee LK, Chu MY, Chen TM, Lipsky MH, Maciag T, Friedman S, Epstein MH, Calabresi P. Inhibition of growth factor mitogenicity and growth of tumor cell xenografts by a sulfonated distamycin A derivative. Pharmacology. 1997;55:269–278. doi: 10.1159/000139538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahama Y, Ochiya T, Tanooka H, Yamamoto H, Sakamoto H, Nakano H, Terada M. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of HST-1/FGF-4 gene protects mice from lethal irradiation. Oncogene. 1999;18:5943–5947. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Min D, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Chung B, Danilenko DM, Farrell C, Lacey DL, Blazar BR, Weinberg KI. Protection from thymic epithelial cell injury by keratinocyte growth factor: a new approach to improve thymic and peripheral T-cell reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;99:4592–4600. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.12.4592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto H, Ochiya T, Tamamushi S, Toriyama-Baba H, Takahama Y, Hirai K, Sasaki H, Sakamoto H, Saito I, Iwamoto T, Kakizoe T, Terada M. HST-1/FGF-4 gene activation induces spermatogenesis and prevents adriamycin-induced testicular toxicity. Oncogene. 2002;21:899–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harjes U, Bensaad K, Harris AL. Endothelial cell metabolism and implications for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1207–1212. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:235–253. doi: 10.1038/nrd2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Presta M, Dell’Era P, Mitola S, Moroni E, Ronca R, Rusnati M. Fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor system in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:159–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albini A, Tosetti F, Li VW, Noonan DM, Li WW. Cancer prevention by targeting angiogenesis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:498–509. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson AC. The process of structure-based drug design. Chem Biol. 2003;10:787–797. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorn M, E Silva MB, Buriol LS, Lamb LC. Three-dimensional protein structure prediction: methods and computational strategies. Comput Biol Chem. 2014;53PB:251–276. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSIBLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole C, Barber JD, Barton GJ. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W197–W201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, van Vlijmen H, Karplus M. Evaluation of comparative protein modeling by MODELLER. Proteins. 1995;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martí-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sánchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiser A, Do RK, Sali A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753–1773. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb viewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laskowsky RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereo chemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris AL, MacArthur MW, Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates. Proteins. 1992;12:345–364. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramachandran GN, Ramakrishnan C, Sasisekharan V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J Mol Biol. 1963;7:95–99. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(63)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, Liang J. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W116–W118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laurie AT, Jackson RM. Q-Site Finder: an energy-based method for the prediction of protein–ligand binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1908–1916. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen R, Li L, Weng Z. ZDOCK: an initial-stage protein docking algorithm. Proteins. 2003;52:80–87. doi: 10.1002/prot.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pierce B, Weng Z. ZRANK: reranking protein docking predictions with an optimized energy function. Proteins. 2007;67:1078–1108. doi: 10.1002/prot.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park MS, Gao C, Stern HA. Estimating binding affinities by docking/scoring methods using variable protonation states. Proteins. 2011;79:304–314. doi: 10.1002/prot.22883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawatkar S, Wang H, Czerminski R, Joseph-McCarthy D. Virtual fragment screening: an exploration of various docking and scoring protocols for fragments using Glide. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2009;23:527–539. doi: 10.1007/s10822-009-9281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitchen DB, Decornez H, Furr JR, Bajorath J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:935–949. doi: 10.1038/nrd1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen IJ, Foloppe N. Drug-like bioactive structures and conformational coverage with the ligprep/confgen suite: comparison to programs MOE and catalyst. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:822–839. doi: 10.1021/ci100026x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vasavi M, Kiran KM, Sarita RP, Uma V. Modeling of alternate RNA polymerase sigma D factor and identification of novel inhibitors by virtual screening. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2012;5:363–374. doi: 10.1007/s12195-012-0238-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durrant JD, Friedman AJ, Rogers KE, McCammon JA. Comparing neural-network scoring functions and the state of the art: applications to common library screening. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53:1726–1735. doi: 10.1021/ci400042y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ioakimidis L, Thoukydidis L, Mirza A, Naeem S, Reynisson J. Benchmarking the reliability of QikProp. Correlation between experimental and predicted values. QSAR Comb Sci. 2008;27:445–456. doi: 10.1002/qsar.200730051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malkhed V, Mustyala KK, Potlapally SR, Vuruputuri U. Identification of novel leads applying in silico studies for mycobacterium multidrug resistant (MMR) protein. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2014;32:1889–1906. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2013.842185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramatenki V, Potlapally SR, Dumpati RK, Vadija R, Vuruputuri U. Homology modeling and virtual screening of ubiquitin conjugation enzyme E2A for designing a novel selective antagonist against cancer. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2015;35:536–549. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2014.969375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh T, Biswas D, Jayaram B. AADS—an automated active site identification, docking and scoring protocol for protein targets based on physicochemical descriptors. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2515–2527. doi: 10.1021/ci200193z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girke T, Cheng LC, Raikhel N. ChemMine. A compound mining database for chemical genomics. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:573–577. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boobis A, Gundert-Remy U, Kremers P, Macheras P, Pelkonen O. In silico prediction of ADME and pharmacokinetics report of an expert meeting organised by COST B15. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2002;17:183–193. doi: 10.1016/S0928-0987(02)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Congreve M, Carr R, Murray C, Jhoti H. A ’rule of three’ for fragment-based lead discovery? Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:876–877. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 245 kb)

(GIF 14 kb)

(GIF 15 kb)

(GIF 18 kb)

(GIF 16 kb)

(GIF 11 kb)

(GIF 11 kb)