Abstract

Microfluidic chip electrophoresis (MCE) is a powerful separation tool for biomacromolecule analysis. However, adsorption of biomacromolecules, particularly proteins onto microfluidic channels severely degrades the separation performance of MCE. In this paper, an anti-protein-fouling MCE was fabricated using a novel sandwich photolithography of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) prepolymers. Photopatterned microchannel with a minimum resolution of 10 μm was achieved. After equipped with a conventional online electrochemical detector, the device enabled baseline separation of bovine serum albumin, lysozyme (Lys), and cytochrome c (Cyt-c) in 53 s under a voltage of 200 V. Compared with a traditional polydimethylsiloxane MCE made by soft lithography, the PEG MCE made by the sandwich photolithography not only eliminated the need of a master mold and the additional modification process of the microchannel but also showed excellent anti-protein-fouling properties for protein separation.

I. INTRODUCTION

Since the first demonstration in 1990,1,2 microfluidic chip electrophoresis (MCE), as a highly integrated and automated portable device, has been developed rapidly with important applications in many areas such as life science, biology, medicine, food, and environmental monitoring,3–7 where entire chemical and bio-analyses in miniaturized volumes are performed with high sensitivities and efficencies.8–14

Organic materials such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) have been used to fabricate MCE.15,16 Compared with inorganic materials, polymers are flexible and inexpensive, and therefore, have become the most commonly used microchip materials. However, the fabrication process of polymeric MCE is usually complicated because an extra mold or template needs to be prepared. For example, Jenkins prepared a PDMS MCE using soft lithography method with photopatterned SU-8 photoresist as templates. The fabrication process included multiple steps such as SU-8 template preparation, molding PDMS, and bonding PDMS by oxygen plasma.17 Sun et al. prepared a PMMA MCE using hot embossing method with a pre-etched metal as molds. The fabrication process included multiple steps such as metal mold preparation, hot embossing PMMA, and bonding PMMA by melting.18 Moreover, adsorption of biomacromolecules, particularly proteins onto the PDMS or PMMA microfluidic channels severely degrades the separation performance of MCE, leading to sample loss, peak broadening, poor resolution, unstable electroosmotic flow (EOF), and long migration times. To suppress the adsorption of proteins onto the microchannel surface, surface modification is a commonly used approach. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is often employed as anti-protein-fouling coatings to modify the microchannels.19,20 For instance, Kitagawa et al. modified PMMA microchannel surface with amino-PEG by nucleophilic addition-elimination reaction to enhance separation performance of the MCE.21 Similarly, a PEG-based surface modification strategy was developed for PDMS microchips to prevent protein adsorption.22

In this work, we report a simple method to fabricate anti-protein-fouling MCE using a novel sandwich photolithography of PEG prepolymers. PEG microchannels with a minimum resolution of 10 μm were achieved. Compared with a PDMS MCE made by soft lithography, the anti-protein-fouling property and protein separation performance of the obtained PEG MCE were investigated and discussed preliminarily.

II. EXPERIMENTAL

A. Materials

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), lysozyme (Lys), cytochrome c (Cyt-c), fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled BSA (FITC-BSA), poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylates (PEGDA) (Mw = 258, and Mw = 575) and 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone (HMP, ≥99.0%) were purchased from Aldrich. PDMS (Sylgard 184) was purchased as a two-component kit that contained the vinyl-terminated base and curing agent from Dow Corning. SU-8 2050 photoresist along with developer was purchased from MicroChem. Monosodium orthophosphate (NaH2PO4·2H2O) and dibasic sodium phosphate (Na2HPO4·12H2O) were bought from Shunqiang Chemical Reagent Company (Shanghai, China). Acetone and isopropanol were obtained from Sanhe Chemical Reagent Company (Tianjin, China). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were purchased from Hongyan Reagent Company (Tianjin, China). Phosphate buffer was used as separation medium, and the pH value was adjusted by NaOH (0.1 M) and H3PO4 (40 mM). The concentrations of BSA, Lys, and Cyt-c in the testing samples were all 0.5 mg ml−1. All solutions were filtered though a 0.45 μm membrane before usage. Fused-silica capillaries of 50 μm ID and 375 μm OD were provided by Yongnian Optic Fiber (Hebei, China).

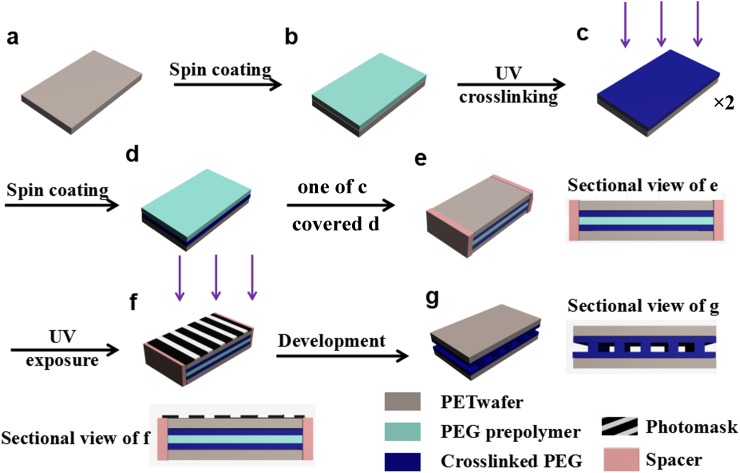

B. Fabrication of PEG MCE by sandwich photolithography

The fabrication process of the PEG microfluidic chip is shown in Fig. 1. The HMP photoinitiator and PEGDA were thoroughly mixed with a weight ratio of 1:30 to form the PEG prepolymer. A transparent polyethylene terephthalate (PET) tape (Chaoan, China) with a thickness of 50 μm was cut into fixed size of 5 cm × 10 cm as the polymer wafer or protection layer for the MCE (Fig. 1(a)). The PEG prepolymer with a thickness of 25–50 μm was spin coated on the tape at a speed of 200–500 rpm (Fig. 1(b)). The UV-crosslinking of the PEG prepolymer layer was carried out at a 365 nm UV (200 mW cm−2) for 3 s using a UV curing system (EXFO Omnicure S1000) with a lamp power of 100 W. After UV crosslinking (Fig. 1(c)), another layer of PEG prepolymer with a thickness of 10–100 μm was spin coated on the UV crosslinked PEG-PET wafer at a speed of 100–800 rpm (Fig. 1(d)). By covering another UV crosslinked PEG-PET wafer (Fig. 1(c)) on the top of the PEG prepolymer layer (Fig. 1(d)) with 10–100 μm spacers, a PET-PEG/PEG prepolymer/PEG-PET sandwich structure was obtained (Fig. 1(e)). After UV exposure at an intensity of 160–200 mW cm−2 for 2.1–3.1 s through a chrome/sodalime photomask, the regions of PEG prepolymer exposed to UV light underwent free radical polymerization and became crosslinked, while unexposed regions were dissolved in deionized water after 15 min development (Fig. 1(f)). Finally, the microchannels were flushed with isopropanol and water for 10 min, respectively. The typical PEG MCE has a separation microchannel dimension of 13.3 cm × 50 μm × 50 μm (Fig. 1(g)). The cross-section images of PEG microchannels were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-6309LV).

FIG. 1.

Illustration of the fabrication process of PEG MCE: (a) PET wafer, (b) PEG prepolymer on PET wafer, (c) UV crosslinked PEG on PET wafer (PEG-PET), (d) PEG prepolymer on PEG-PET (PEG prepolymer/PEG-PET), (e) PET-PEG/PEG prepolymer/PEG-PET sandwich structure, (f) UV exposure through a photomask, (g) obtained PEG microchannel after development.

C. Fabrication of PDMS MCE by soft lithography

The PDMS microfluidic chip with a separation microchannel dimension of 13.3 cm × 50 μm× 50 μm was fabricated by using a photopatterned SU-8 template. The PDMS prepolymer was first prepared by mixing the PDMS base and the curing agent in a 10:1 (w/w) ratio. The PDMS prepolymer was degassed for 15 min to remove air bubbles formed during mixing, and then the PDMS prepolymer was poured onto the SU-8 template. After thermal curing at 80 °C for 2 h, it formed a replica of the SU-8 template with well-defined opening microchannels. After covalently bonded with another piece of PDMS through free radical reactions generated in oxygen plasma (at 30 W for 30 s), the PDMS MCE was packaged. Finally, the microchannels were flushed with isopropanol and water for 10 min, respectively.

D. Anti-protein-fouling tests

Protein adsorption within PEG/PDMS microchannels was measured as follows: FITC-BSA was dissolved in 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.0) at a concentration of 0.05 mg·ml−1, and pumped through the capillaries for 30 min at a flow rate of 5 μl·min−1. Then, the capillaries were rinsed thoroughly with the buffer and subsequently analyzed using an inverted fluorescent microscope (Axiovert 200, Zeiss, 488 nm excitation and 530 nm detection). Fluorescent images of various samples were taken and quantified using NIH-Scion Image viewer. Bare silica capillaries analyzed under the same light exposure were used as background controls. PEG surface modified silica capillaries were fabricated according to a method reported elsewhere.23

E. Separation of proteins by MCE

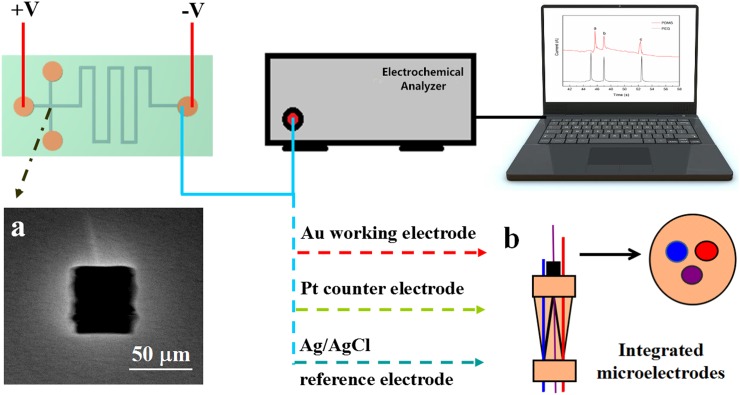

As shown in Fig. 2, the electrochemical measurements were adopted to detect the samples using a CHI-832C electrochemical analyzer (CH Instruments, China) at room temperature. An integrated microelectrode system, which was specially designed for low voltage detection as reported elsewhere,24 was put into the detection reservoir with a Pt wire (CHI-115) as counter electrode, a bare gold electrode (CHI-105) as working electrode, and a Ag/AgCl electrode (CHI-111) as reference electrode. Before electrophoresis, the PEG/PDMS microchannel was flushed with 100 mM NaOH solution and deionized water, and then filled with 40 mM phosphate buffer solution (pH = 6.0) from the reservoirs. Meanwhile, the mixed sample of BSA, Lys, and Cyt-c (0.5 mg ml−1 for each protein) was injected via an electrokinetic injection system from the injection channel for 2 s. Finally, a direct current voltage of +200 V was applied to the two buffer reservoirs to start the MCE separation, and the detection signal was recorded by the online electrochemical analyzer in a current-time mode. The pH values of solutions were measured with a PB-10 pH meter (Renhe Instruments, China). All the measurements were performed at 25 °C.

FIG. 2.

Illustration of the experimental setup for PEG/PDMS MCE. Inset (a) shows a microscope section image of the PEG microfluidic channels. Inset (b) shows an illustration of the integrated microelectrode system.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Fabrication of PEG MCE by sandwich photolithography

To determine the effect of PEG prepolymers on microchannel fabrication, PEG prepolymers with different molecular weights were tested. We found that a high molecular weight PEG prepolymer (Mw = 575) had poor mechanical properties after crosslinking and could not resist swelling in water, while the low molecular weight PEG prepolymer (Mw = 258) had good mechanical properties and could resist swelling in water because a low molecular weight prepolymer renders a high crosslinking density.

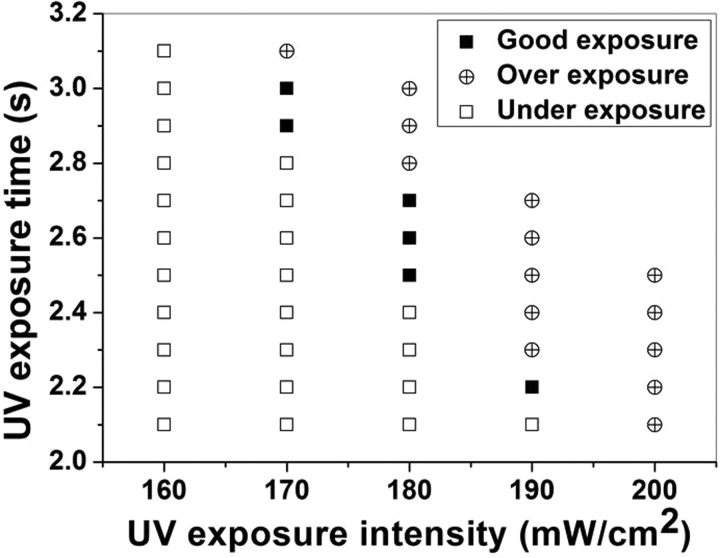

In the sandwich photolithography, because there is a PET-PEG layer with a thickness of ∼75 μm between the photomask and the PEG preploymer layer, UV exposure conditions are important parameters to determine the formation of PEG microchannels. If the UV exposure time is too long at a fixed UV intensity, PEG prepolymer would be over exposed and cause clogging of the microchannels. If the UV exposure time is too short, PEG prepolymer would be under exposed and cause collapse of the microchannels. As shown in Fig. 3, the optimal UV exposure conditions were determined using microchannel of 50 μm in width and 50 μm in height as an example.

FIG. 3.

Diagram of optimizing the UV exposure conditions for the sandwich photolithography.

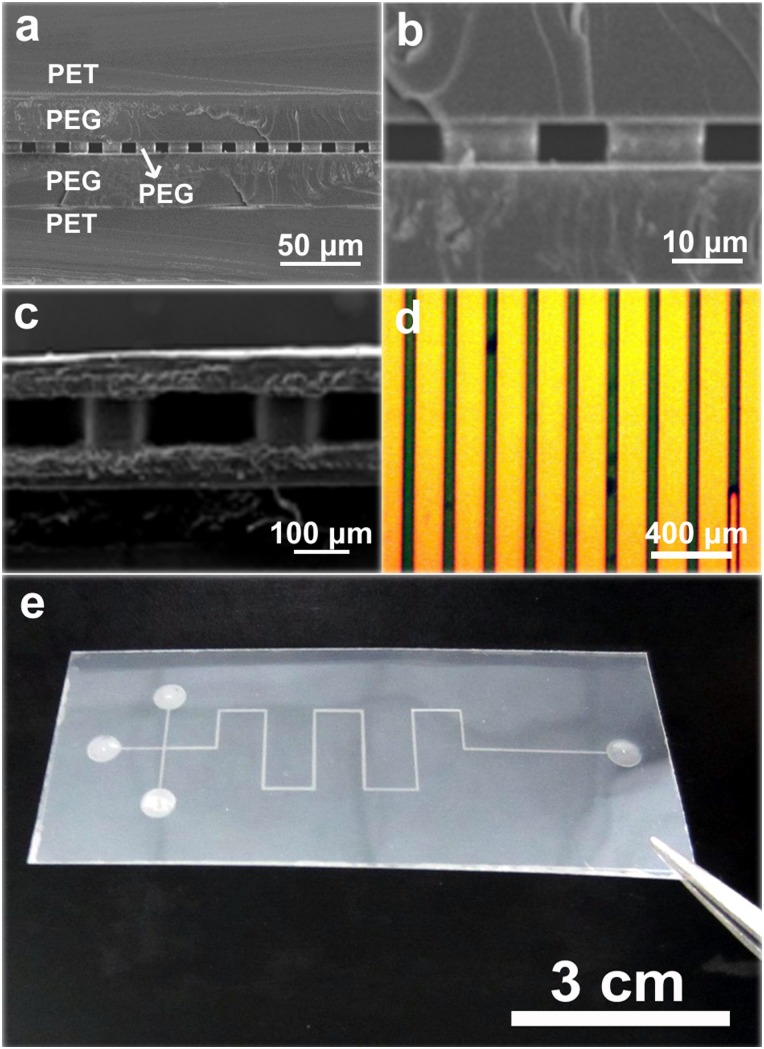

Fig. 4 shows the SEM images and optical photos of the PEG MCE fabricated by the sandwich photolithography. The channel width ranges from 10 μm to 200 μm, and the channel height ranges from 10 iμm to 100 μm (Figs. 4(a)–4(c)). From Fig. 4(a), we can clear see the PET-PEG/PEG/PEG-PET sandwich structure of the formed PEG microchannels. After the sandwich photolithography, the PET tape layers were bonded to the PEG layers by strong adhesive forces and could act as extra protection layers for the PEG microchannels. Fig. 4(d) shows the top view of typical 50 μm size microchannels filled with colored water, and Fig. 4(e) shows the typical PEG MCE with a separation microchannel length of 13.3 cm.

FIG. 4.

Cross-sectional SEM images (a)–(c) and optical photos (d) and (e) of various PEG microchannels: (a) and (b) 10 μm width, 6 μm height; (c) 200 μm width, 100 μm height; (d) 50 μm width, 50 μm height, filled with colored water; (e) PEG MCE with 13.3 cm length separation microchannels.

B. Anti-protein-fouling property of PEG microchannel

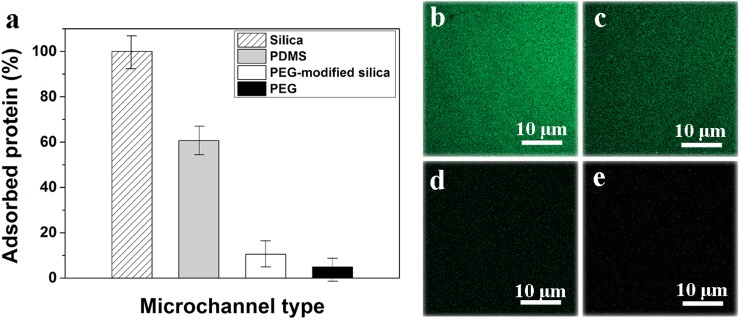

Fig. 5(a) shows the potency of PEG microchannel in preventing FITC-BSA adsorption. Compared with bare silica microchannel, the PDMS microchannel shows ∼39% inhibition of protein adsorption, and the PEG-modified silica microchannel shows ∼89% inhibition of protein adsorption, while the PEG microchannel can inhibit protein adsorption by as much as ∼95%. Since the PEG microchannels are transparent under microscope (Fig. 4(d)), they have little effect on the fluorescence detection. As shown in Fig. 5(b)–5(e), protein adsorption was greatly reduced inside PEG-modified silica and PEG channels compared to the silica and PDMS channels. However, the preparation process of PEG surface modified capillary is usually complicated which includes multi-steps such as capillary pretreatment, introducing coupling agents, and inserting target coating reagents.25,26 Moreover, highly toxic and moisture sensitive silane coupling agents are traditionally used in the surface modification, which often cause environmental and quality problems during the manufacture and application.27,28

FIG. 5.

Efficacy of PEG microchannel in preventing protein adsorption (a) and fluorescent images of FITC-BSA adsorption in silica (b), PDMS (c), PEG-modified silica (d), and PEG (e) microchannels.

The superior anti-protein-fouling property of the PEG microchannels should come from its high surface resistance to non-specific adsorption of proteins in aqueous environment.29,30 Based on entropy model,31,32 PEG chains can assume a wide range of conformations in water and require a certain volume, the “restricted volume.” As the protein approaches the surface, it compresses the PEG chains, which leads to an entropy loss of the polymer chains and accordingly to a decrease in the Gibbs free energy of the system, which makes the diffusion of the protein into the layer energetically unfavorable.

C. Protein separation performance of PEG MCE

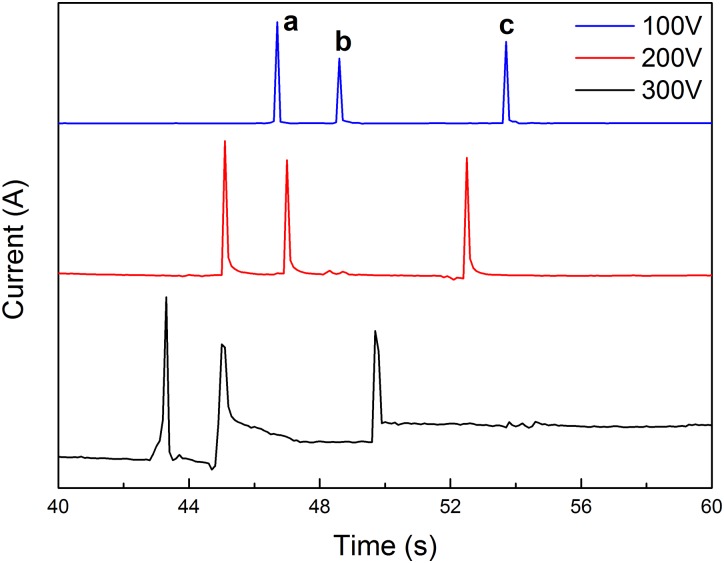

Fig. 6 shows the separation of a mixture of three proteins (BSA, Lys, and Cyt-c) using the PEG MCE equipped with electrochemical detector at different voltages. The three proteins are completely separated in less than 55 s, indicating the high separation efficiency of the PEG MCE. Nevertheless, applied voltage value has obvious influence on protein separation performance. When the voltage is too high, considerable Joule heat would be generated, leading to the baseline fluctuation. When the voltage is too low, the separation efficiency would be decreased. When the applied voltage value is 200 V, protein separation efficiency of the PEG MCE is relatively better. Due to the limitation of the integrated microelectrode system which is specially designed for low voltage detection,24 higher voltages such as more than 300 V are not tested in this study.

FIG. 6.

Separation of three proteins under different voltages using PEG MCE. Conditions: buffer, 40 mM phosphate (pH = 6.0); sample, 0.5 mg·ml−1 for each protein; microchannel, 14 cm × 50 μm × 50 μm (13.3 cm effective); temperature, 25 °C. Peak identification: (a) Cyt-c; (b) Lys; (c) BSA.

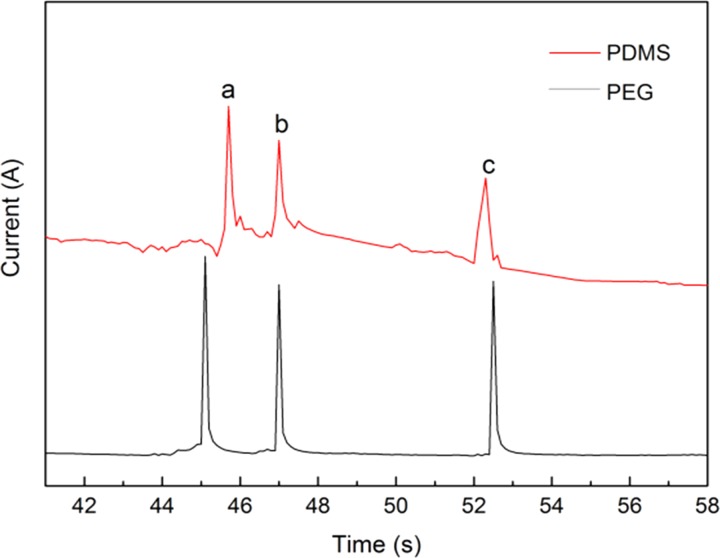

The comparison of the PEG MCE with traditional PDMS MCE in protein separation performance is shown in Fig. 7. The PEG MCE enabled baseline separation of BSA, Lys, and Cyt-c in 53 s. All the peaks were almost symmetrical Gaussian shape without peak broadening for PEG MCE, indicating the excellent resistance of the PEG microchannels for protein adsorption.33,34 In comparison at the same conditions, the separation peaks were remarkably broadened and the baseline was fluctuated strongly in the PDMS MCE, due to strong adsorption of proteins onto microchannel surfaces. Therefore, the anti-protein-fouling PEG MCE performs much better than the traditional PDMS MCE in separation of protein samples.

FIG. 7.

Comparison of the anti-protein-fouling PEG MCE with traditional PDMS MCE in protein separation performance. Separation conditions: buffer, 40 mM phosphate (pH = 6.0); applied voltage, +200 V; sample, 0.5 mg·ml−1 for each protein; microchannel, 14 cm × 50 μm × 50 μm (13.3 cm effective); temperature, 25 °C. Peak identification: (a) Cyt-c; (b) Lys; (c) BSA.

Table I shows that the run-to-run (n = 5) relative standard deviation (RSD) of migration time for the proteins in the PEG MCE is less than 1%, day-to-day (n = 5) RSD is less than 2%, and chip-to-chip (n = 5) RSD is less than 3%. The detection limits for Cyt-c, Lys, and BSA are 0.01234, 0.01246, and 0.00257 mM, respectively. The detection limits can be further improved if more sensitive detection techniques such as online laser induced fluorescence detection system and mass spectrometry detector are applied.35–38

TABLE I.

RSDs of migration time for proteins of the PEG MCE.

| Proteinsa | Run to run (n = 5) | Day to day (n = 5) | Chip to chip (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migration time | Migration time | Migration time | |

| Cyt-c | 0.41 | 1.16 | 2.37 |

| Lys | 0.89 | 1.48 | 2.68 |

| BSA | 0.57 | 1.35 | 2.56 |

Separation conditions: the same as Fig. 7.

Recently, Kim et al. presented a method to fabricate microchannels comprised entirely of crosslinked PEG by UV-assisted irreversible sealing to bond partially crosslinked PEG surfaces.39 However, the method is based on soft lithography which needs a master mold of silicon. Although it can be robust and reusable, the molding process creates microfabrication compatibility and integration issues, for instance, misalignment and packaging problems to another substrate. Compared with these traditional soft lithography methods,24,39 the sandwich photolithography method of PEG prepolymers eliminates the need of a master mold, the need of alignment, and the additional modification process, provides a more facile and efficient way to rapid prototyping of anti-protein-fouling microfluidic chips.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

In this work, a simple and effective method for fabricating anti-protein-fouling PEG microfluidic chips using sandwich photolithography is developed successfully. Using this strategy, PEG MCEs were fabricated successfully with the PEG microchannel sizes ranging from 10 μm to 200 μm. The PEG microchannels showed excellent resistant property against protein adsorption with respect to silica capillary or PDMS microchannels. The anti-protein-fouling PEG MCE performs much better than the traditional PDMS MCE in separation of protein samples. Three kinds of proteins were completely resolved with a migration time less than 53 s using the PEG microchip at optimized conditions. Furthermore, the PEG MCE exhibited good stability and repeatability. Compared with the traditional soft lithography method, the sandwich photolithography method of PEG prepolymers eliminated the need of a master mold, the need of alignment, and the additional modification process of the microchannel, provided a more facile and efficient way to rapid prototyping of anti-protein-fouling microfluidic chips.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21375069, 21404065, and 21574072), the Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scientists of Shandong Province (JQ201403), the Project of Shandong Province Higher Educational Science and Technology Program (J15LC20), the Graduate Education Innovation Project of Shandong Province (SDYY14028), the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars of State Education Ministry (No. 20111568), the Open Research Fund Program of Beijing Molecular Science National Laboratory (No. 20140123), and the Postdoctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Qingdao.

References

- 1. Manz A., Graber N., and Widmer H. M., Sens. Actuator B: Chem. , 244 (1990). 10.1016/0925-4005(90)80209-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harrison D. J., Manz A., Fan Z., Luedi H., and Widmer H. M., Anal. Chem. , 1926 (1992). 10.1021/ac00041a030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ortega Í., Ryan A. J., Deshpande P., MacNeil S., and Claeyssens F., Acta Biomater. , 5511 (2013). 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verhulsel M., Vignes M., Descroix S., Malaquin L., Vignjevic D. M., and Viovy J. L., Biomaterials , 1816 (2014). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Puchberger-Enengl D., Podszun S., Heinz H., Hermann C., Vulto P., and Urban G. A., Biomicrofluidics , 044111 (2011). 10.1063/1.3664691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang J., Coulston R. J., Jones S. T., Geng J., Scherman O. R., and Abell C., Science , 690 (2012). 10.1126/science.1215416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stoll H., Kiessling H., Stelzle M., Wendel H. P., Schütte J., Hagmeyer B., and Avci-Adali M., Biomicrofluidics , 034111 (2015). 10.1063/1.4922544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arora A., Simone G., Salieb-Beugelaar G. B., Kim J. T., and Manz A., Anal. Chem. , 4830 (2010). 10.1021/ac100969k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Culbertson C. T., Mickleburgh T. G., Stewart-James S. A., Sellens K. A., and Pressnall M., Anal. Chem. , 95 (2014). 10.1021/ac403688g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Song S. H., Lim C. S., and Shin S., Biomicrofluidics , 064101 (2013). 10.1063/1.4829095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhuang Z., Starkey J. A., Mechref Y., Novotny M. V., and Jacobson S. C., Anal. Chem. , 7170 (2007). 10.1021/ac071261v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haghighi F., Talebpour Z., and Sanati-Nezhad A., Lab Chip , 2559 (2015). 10.1039/C5LC00283D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paracha S. and Hestekin C., Biomicrofluidics , 033105 (2016). 10.1063/1.4954051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gottschlich N., Jacobson S. C., Culbertson C. T., and Ramsey J. M., Anal. Chem. , 2669 (2001). 10.1021/ac001019n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mechref Y. and Novotny M. V., Mass Spectrom. Rev. , 207 (2009). 10.1002/mas.20196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shang F., Guihen E., and Glennon J. D., Electrophoresis , 105 (2012). 10.1002/elps.201100454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jenkins G., Method Mol. Biol. , 153 (2013). 10.1007/978-1-62703-134-9_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun X., Peeni B. A., Yang W., Becerril H. A., and Woolley A. T., J. Chromatogr. A , 162 (2007) 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gao C. L., Sun X. H., and Woolley A. T., J. Chromatogr. A , 92 (2013). 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.03.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bi H., Meng S., Li Y., Guo K., Chen Y., Kong J., Yang P., Zhong W., and Liu B., Lab Chip , 769 (2006). 10.1039/b600326e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitagawa F., Kubota K., Sueyoshi K., and Otsuka K., J. Pharm. Bio. Anal. , 1272 (2010). 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang Z., Feng X., Luo Q., and Liu B. F., Electrophoresis , 3174 (2009). 10.1002/elps.200900132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu B., Cui W., Cong H., Jiao M., Liu P., and Yang S., RSC Adv. , 20010 (2013). 10.1039/c3ra23328f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cong H., Xu X., Yu B., Liu H., and Yuan H., Biomicrofluidics , 024107 (2016). 10.1063/1.4943915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tuma P., Samcova E., and Stulik K., Anal. Chim. Acta , 84 (2011). 10.1016/j.aca.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lokajova J., Tiala H. D., Viitala T., Riekkola M. L., and Wiedmer S. K., Soft Matter , 6041 (2011). 10.1039/c1sm05372h [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Omae K., Sakai T., Sakurai H., Yamazaki K., Shibata T., Mori K., Kudo M., Kanoh H., and Tati M., Arch. Toxicol. , 750 (1992). 10.1007/BF01972626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clayton G. D. and Clayton F. E., Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology ( Wiley, New York, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Worz A., Berchtold B., Moosmann K., Prucker O., and Ruhe J., J. Mater. Chem. , 19547 (2012). 10.1039/c2jm30820g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gu M. H., Kilduff J. E., and Belfort G., Biomaterials , 1261 (2012). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jeon S. I. and Andrade J. D., J. Colloid Interface Sci. , 149 (1991). 10.1016/0021-9797(91)90043-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Szleifer I., Biophys. J. , 595 (1997). 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78698-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sueyoshi K., Hori Y., and Otsuka K., Microfluid. Nanofluid. , 933 (2013). 10.1007/s10404-012-1100-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Albrecht J. C., Kotani A., Lin J. S., Soper S. A., and Barron A. E., Electrophoresis , 590 (2013). 10.1002/elps.201200462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu B., Liu P., Cong H., Tang J., and Zhang L., Electrophoresis , 3066 (2012). 10.1002/elps.201200245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Akbar M., Shakeel H., and Agah M., Lab Chip , 1748 (2015). 10.1039/C4LC01461H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cong H., Xu X., Yu B., Yuan H., Peng Q., and Tian C., J. Micromech. Microeng. , 053001 (2015). 10.1088/0960-1317/25/5/053001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Black W. A., Stocks B. B., Mellors J. S., Engen J. R., and Ramsey J. M., Anal. Chem. , 6280 (2015). 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim P., Jeong H. E., Khademhosseini A., and Suh K. Y., Lab Chip , 1432 (2006). 10.1039/b610503c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]