Abstract

In the developing brain, growth and differentiation are intimately linked. Here, we show that in the zebrafish embryo, the homeodomain transcription factor Rx3 coordinates these processes to build the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus. Analysis of rx3 chk mutant/rx3 morphant fish and EdU pulse-chase studies reveal that rx3 is required to select tuberal/anterior hypothalamic progenitors and to orchestrate their anisotropic growth. In the absence of Rx3 function, progenitors accumulate in the third ventricular wall, die or are inappropriately specified, the shh+ anterior recess does not form, and its resident pomc+, ff1b+ and otpb+ Th1+ cells fail to differentiate. Manipulation of Shh signalling shows that Shh coordinates progenitor cell selection and behaviour by acting as an on-off switch for rx3. Together, our studies show that Shh and Rx3 govern formation of a distinct progenitor domain that elaborates patterning through its anisotropic growth and differentiation.

KEY WORDS: Hypothalamus development, Anterior hypothalamus, Rx3, Sonic hedgehog, Tuberal hypothalamus, Zebrafish hypothalamus

Summary: During zebrafish tuberal/anterior hypothalamus development, Shh and Rx3 govern the formation of a distinct progenitor domain that elaborates pattern through its anisotropic growth and differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

The hypothalamus is an ancient part of the ventral forebrain. It centrally regulates homeostatic processes that are essential to survival and species propagation, including autonomic regulation of energy balance, growth, stress and reproduction. Such adaptive functions are dependent upon the integrated function of evolutionarily conserved neurons (reviewed by Bedont et al., 2015; Biran et al., 2015; Burbridge et al., 2016; Löhr and Hammerschmidt, 2011; Machluf et al., 2011; Pearson and Placzek, 2013; Puelles et al., 2012) that, in mouse, are located within defined nuclei, including the arcuate nucleus (Arc) and ventromedial nucleus (VMN) of the tuberal hypothalamus, and the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the anterior hypothalamus. In zebrafish, functionally analogous neurons exist in the periventricular tuberal (pevTub) hypothalamus and the neurosecretory preoptic (NPO) area (Biran et al., 2015; Herget et al., 2014; see Materials and Methods and Discussion for terminology). Many transcription factors and signalling ligands that govern differentiation of hypothalamic neurons from progenitor cells have also been largely conserved (reviewed by Bedont et al., 2015; Biran et al., 2015; Burbridge et al., 2016; Pearson and Placzek, 2013; Puelles et al., 2012).

The mechanisms through which secreted signalling ligands and transcription factors define and build hypothalamic territories and cells remain enigmatic (see Bedont et al., 2015; Puelles et al., 2012; Pearson and Placzek, 2013). Models based on the uniform growth and differentiation of patterned territories do not account for the complex spatial patterns of the hypothalamus or the protracted period of hypothalamic neuronal differentiation and, at present, little is known about how early patterning events are elaborated over time. In the hypothalamus, distinct neural progenitor domains that form around the third (diencephalic) ventricle (3V) are not as well-characterized as those in other regions of the CNS. Moreover, the third ventricle is sculpted into the infundibular, optic, and other smaller and ill-defined recesses in mammals (Amat et al., 1992; O'Rahilly and Muller, 1990), and lateral (LR), posterior (PR) and anterior (AR) recesses in zebrafish (Wang et al., 2009, 2012). Three unexplored questions are when such hypothalamic recesses form, whether they are composed of distinct progenitor cells and whether their appearance correlates with the emergence of particular neuronal subsets.

The paired-like homeodomain transcription factor Rax (also known as Rx) and its fish orthologue, rx3, are expressed within retinal and hypothalamic progenitors (Bailey et al., 2004; Bielen and Houart, 2012; Cavodeassi et al., 2013; Chuang et al., 1999; Furukawa et al., 1997; Lu et al., 2013; Mathers et al., 1997; Stigloher et al., 2006; Medina-Martinez et al., 2009; Muranishi et al., 2012; Pak et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2000) and play a central role in eye development. Disruption of Rx leads to small or absent eyes in mouse (Bailey et al., 2004; Mathers et al., 1997; Medina-Martinez et al., 2009; Muranishi et al., 2012; Zhang et.al., 2000) and is associated with anophthalmia in humans (Voronina et al., 2004). In zebrafish, loss of function of Rx3, including mutation in the zebrafish rx3 gene (chk mutant), disrupts eye morphogenesis (Kennedy et al., 2004; Loosli et al., 2003; Stigloher et al., 2006): retinal progenitors are specified, but remain trapped in the lateral wall of the diencephalon, failing to undergo appropriate migration (Rembold et al., 2006) and differentiation (Stigloher et al., 2006).

In addition to its well-documented role in eye formation, Rx/rx3 governs hypothalamic development. Rx-null mice show variable penetrance, but all display abnormalities in the ventral hypothalamus (Mathers et al., 1997; Medina-Martinez et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2000). Lineage-tracing studies demonstrate that Rx+ progenitors give rise to Sf1 (Nr5a1)+ VMN and Pomc+ Arc tuberal neurons, and targeted ablation of Rx in a subset of VMN progenitors leads to a fate switch from an Sf1+ VMN identity to a Dlx2+ dorsomedial nucleus (DMN) identity (Lu et al., 2013). These studies suggest that Rx functions in progenitor cells to cell-autonomously select Sf1+ VMN and Pomc+ Arc identities. In zebrafish, chk mutants and rx3 morphants similarly show reduced numbers of pevTub pomc+ neurons and additionally decreased NPO avp+ (formerly vt, arginine vasotocin) neurons (Dickmeis et al., 2007; Tessmar-Raible et al., 2007), although currently the underlying mechanism is unclear. These studies, together, raise the possibility that Rx/rx3 plays a widespread role in the differentiation of tuberal and anterior/NPO hypothalamic neurons.

In mice, expression of the secreted signalling ligand Shh overlaps with that of Rx (Shimogori et al., 2010) and conditional ablation of Shh from the anterior-basal hypothalamus results in phenotypes that resemble the loss of Rx, including a reduction/loss of Avp+ PVN and Pomc+ Arc neurons (Shimogori et al., 2010; Szabo et al., 2009). As yet, however, the link between Shh and Rx/Rx3 remains unclear and the mechanisms that operate downstream of Shh and Rx/Rx3 to govern hypothalamic differentiation are unresolved.

Here, we analyse rx3 and shh expression and function in the developing zebrafish hypothalamus. Analysis of chk mutant and rx3 morphant fish, together with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) pulse-chase experiments, show that Rx3 is required for a switch in progenitor domain identity, and for the survival and anisotropic growth of tuberal/anterior progenitors, including their progression to rx3−shh+ AR cells and to pomc+, ff1b (nr5a1a)+ and otpb+ Th1 (Th)+ tuberal/anterior fates. Timed delivery of cyclopamine or SAG reveals that Shh signalling governs these processes via dual control of rx3 expression, inducing then downregulating it. We demonstrate that rx3 downregulation, mediated by Shh signalling, is an essential component of Rx3 function: failure to downregulate rx3 leads to the failure of anisotropic growth, loss of the shh+rx3− AR and failure of tuberal/anterior cell differentiation. Together, our studies reveal a mechanism that elaborates early patterning around the hypothalamic ventricle by the selective growth of distinct progenitor cells.

RESULTS

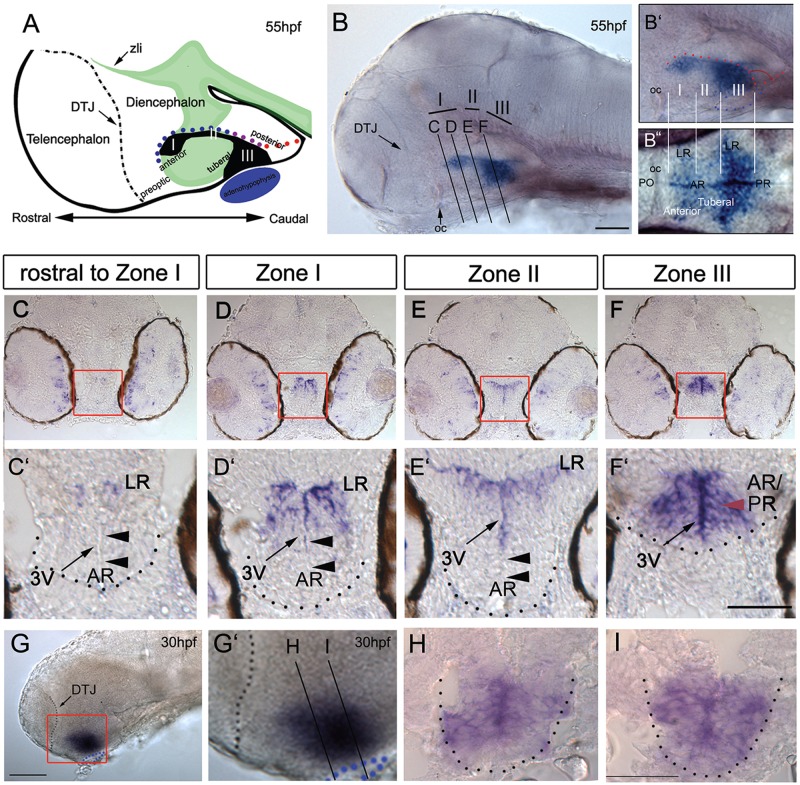

rx3 expression in third ventricle cells

Previous studies have described zebrafish rx3 expression (Bielen and Houart, 2012; Cavodeassi et al., 2013; Chuang et al., 1999; Kennedy et al., 2004; Loosli et al., 2003; Stigloher et al., 2006) but have not performed a detailed analysis in the 2- to 3-day embryo. Neurons in the hypothalamus, including pomc+ and avp+ neurons that are decreased/lost in the absence of rx3 (Dickmeis et al., 2007; Tessmar-Raible et al., 2007) begin to differentiate over the first 2-3 days of development (Liu et al., 2003; Dickmeis et al., 2007; Tessmar-Raible et al., 2007) and we therefore focused on this period. At 55 hours post-fertilization (hpf), rx3 is detected in three adjacent zones in the hypothalamus (Fig. 1A-B″). In keeping with mouse nomenclature (Lu et al., 2013), we term these zones I, II and III, characterized by the thin strip of weakly rx3-positive [rx3(weak+)] cells in zone II. Sections show that at its rostral limit, in zone I, rx3 is expressed in neuroepithelial-like cells around the AR and LR of the third ventricle (Fig. 1C,D) but is excluded from the AR tips (Fig. 1C′D′, arrowheads). In zone II, rx3 labels cells that closely line the AR/LR, again excluded from the AR tips (Fig. 1E,E′, arrowheads). In zone III, rx3 marks neuroepithelial-like cells around the third ventricle, which in this region (between anterior and posterior recesses, see Fig. 1A,B″) is small (Fig. 1F,F′). At 30 hpf, the entire third ventricle is small and lined throughout by rx3+ neuroepithelial-like cells (Fig. 1G-I). Thus, the well-defined recesses of the third ventricle, and characteristic rx3+ profiles, develop over 30-55 hpf.

Fig. 1.

rx3 expression around the third ventricle. (A) Schematic of 55 hpf forebrain indicating subdivisions of hypothalamus relative to the rostro-caudal axis and adenohypophysis (blue oval). Green and black show shh (Fig. 3) and rx3 expression. Dots depict rostro-caudal position of AR (blue) and PR (red) next to zone III (purple). (B-B″) Whole-mount 55 hpf embryo after rx3 in situ hybridization. In B, lines show planes of section shown in C-F. In B′,B″ side and ventral views are aligned (white lines) and show position of rx3 relative to morphological landmarks (oc, optic commissure; PO, preoptic hypothalamus). (C-F′) Representative serial sections through a single embryo: bottom panels show high-power views of boxed regions. Red arrowheads point to zone III neuroepithelial-like cells; black arrowheads point to rx3− cells in AR tips. (G-I) Whole-mount side view of 30 hpf embryo after rx3 in situ hybridization; lines in G′ show planes of sections shown in H,I. Dotted lines in C′-F′,H,I delineate outline of ventral hypothalamus, and in G,G′ delineate DTJ. zli, zona limitans intrathalamica. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Tuberal/anterior hypothalamus elongates from proliferating rx3+ progenitors

To determine the position of rx3+ cells relative to other hypothalamic regions, we compared rx3 expression with that of emx2 and fgf3, which mark the posterior, ventro-tuberal and dorso-anterior hypothalamus (Herzog et al., 2004; Kapsimali et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2013; Mathieu et al., 2002), and with the position of the adenohypophysis and the diencephalic-telencephalic junction (DTJ), which are morphologically distinct landmarks. Over 30-55 hpf, rx3 expression is rostral and largely complementary to emx2, and is sandwiched between ventro-tuberal and dorso-anterior fgf3+ cells (Fig. 2A-H′, schematics in 2O), and in zone III it overlies the adenohypophysis. This suggests that throughout 30-55 hpf rx3 demarcates cells at the boundary of the posterior and tuberal/anterior hypothalamus.

Fig. 2.

Anterior/tuberal hypothalamus elongates from rx3+ progenitors. (A-H′) Side views after single or double FISH at 30 hpf (A-D) and 55 hpf (E-H; E′-H′ show high-power views of boxed regions). Arrows in A,C,E,G show distances measured for growth comparisons. Arrowheads in E′,F′ indicate position of recesses (colour-coded as in Fig. 1A). (I-K) Maximum intensity projections of representative sections through 30 hpf embryos. I,J show serial adjacent sections; I′,J′ show single-channel views. Arrowheads show co-labelled (yellow) or single-labelled (green) cells. T-shaped white dotted lines indicate outline of AR and LR. (L,L′) Side views of 55 hpf embryo; L′ shows single-channel view. (M,M′) Representative single-plane views taken through zone II; M′ shows single-channel view. Yellow arrowheads show double-labelled cells; green arrowheads point to phosH3+ rx3− cells at recess tips. (N) Quantitative analyses of cycling cells at 30-55 hpf as indicated by phosH3 expression in rx3+ cells, rx3− cells or in cells adjacent (adj.) to rx3+ cells. (O) Schematic depicting rx3, fgf3 and emx2 expression, and change in length and axial orientation of hypothalamus. A ‘bending’ of the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus occurs over 30-55 hpf, relative to the rostro-caudal axis. Red arrows indicate length of dorsal diencephalon or length of emx2+ PH; white arrows indicate length of rx3+ territories; blue arrows indicate distance from DTJ to rx3+ zone III. (P) Length from DTJ to rostral tip of rx3+ zone III (n=5 embryos each at 30, 40, 48, 55 hpf). (Q) Tuberal/anterior hypothalamus grows approx. 2.5-fold more than dorsal diencephalon, emx2+ PH or ventral rx3+ zone III (n=10 each; P<0.0001). Dotted and dashed lines delineate ventral hypothalamus and T-shaped AR/LR (white), adenohypophysis (blue) and rx3-expressing domain (red). AH, anterior hypothalamus; dA, dorso-anterior; PH, posterior hypothalamus; TH; tuberal hypothalamus; vT, ventral tuberal. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Prior to 30 hpf, rx3 is expressed in progenitor cells (Bielen and Houart, 2012; Cavodeassi et al., 2013; Loosli et al., 2003; Rembold et al., 2006; Stigloher et al., 2006) and the third ventricle is known to harbour cycling cells (Bosco et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009, 2012; Wullimann et al., 1999). To address directly whether 30 hpf rx3+ cells proliferate, we pulsed fish with EdU, culled immediately, and analysed sections for EdU and rx3 expression (Fig. 2I). At 30 hpf, 77% EdU+ cells are rx3+ and the remainder immediately abut rx3+ cells (Fig. 2I,I′; n=110 cells, 4 embryos). Co-analysis of alternate sections with EdU and phosphorylated histone H3 antibody (phosH3) shows that cells in S phase progress to M phase (Fig. 2J,J′). Analysis of control embryos with phosH3 and rx3 confirms that the majority of cycling cells at 30 hpf are rx3+ (68% phosH3+ cells co-express rx3; 32% phosH3+ cells abut rx3+ cells; Fig. 2K,N; n=76 cells, 4 embryos). Whole-mount views of embryos double-labelled with rx3 and phosH3 suggests that by 55 hpf, fewer cycling cells are rx3+ (Fig. 2L,L′). Sections confirm this, showing that at 55 hpf 35% cycling cells are rx3+, 28% abut rx3+ cells but 38% are now detected in the rx3− recess tips (Fig. 2M,N; n=92 cells, 4 embryos).

Although expressed in proliferating cells, the rostro-caudal length of rx3 expression in zones I and III does not change over 30-55 hpf (Fig. 2A,E,O,P) indicating its dynamic regulation. Proliferation correlates, though, with rostro-caudal growth of the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus (Fig. 2A,E,O,P). Growth is greatest over 30-48 hpf (Fig. 2P), and is 2.5-fold greater than rostro-caudal growth of the posterior hypothalamus or the dorsal diencephalon over this period (Fig. 2Q). In summary, the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus shows anisotropic growth over 30-55 hpf, driven from proliferating rx3+ cells and their immediate neighbours.

Development of rx3−shh+ AR and tuberal/anterior immature neurons

We next characterized the growing tuberal/anterior hypothalamus. At 30 hpf, shh is detected uniformly in the hypothalamus (Fig. 3A,A′): double-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis reveals extensive co-expression with rx3 (Fig. 3D,D′, yellow arrowheads). rx3+shh+ cells are bound rostrally and ventrally by rx3+shh− cells (Fig. 3D′, red arrowheads) and caudally/dorsally by shh+ cells (Fig. 3D′, green arrowhead). In the co-expressing region, rx3 is strongest dorso-caudally (Fig. 3D′). Similar expression domains are detected at 55 hpf (Fig. 3B,E) but a novel shh+rx3− domain now projects in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus (Fig. 3B,E,F,F′, white arrowheads). This domain appears to be composed of cells that have downregulated rx3, resulting in the characteristic zone II, but is significantly (1.5-fold) longer at 55 hpf compared with 30 hpf (Fig. 3D,E, white arrows). Analysis of sections shows that in this domain, shh is restricted to cells that line the AR/LR (Fig. 3F′) and shows that shh+rx3− cells define the AR tips (Fig. 3F′, arrowheads; Fig. S1A,A′,C, red arrowheads). Our data show that zone II is characterised by shh+ AR cells, and, together with our previous data, suggests that AR tip cells are shh+rx3− progenitors that derive from adjacent rx3+shh+ progenitors.

Fig. 3.

Differentiation in the 30-55 hpf anterior/tuberal hypothalamus. (A-N) Side views (A,B,D,E,G-J,L-N), ventral views (C,F), sagittal (K) or transverse (K″,M″) sections of 30 hpf and 55 hpf embryos. A′,M′ show high-power views of boxed regions. In B′,E′,F, white arrowheads point to shh(weak+) AR cells; in H′, to otpb+ cells in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus; in M′,N, to hypothalamic pomc+ cells. In D′,E′, arrowheads point to rx3+shh+ cells (yellow), rx3+ cells (red) or shh+ cells (green). (O,P) Schematics depicting expression domains at 30 hpf (O) or 55 hpf (P). AH, anterior hypothalamus; PH, posterior hypothalamus; PO, preoptic hypothalamus; TH; tuberal hypothalamus. Scale bars: 50 µm.

In zebrafish, immature tuberal/anterior hypothalamic neurons can be characterized through expression of the transcription factor otpb (Eaton and Glasgow, 2007; Löhr et al., 2009; Herget et al., 2014; Manoli and Driever, 2014), the nuclear receptor Nr5a1/Sf1 orthologue ff1b (Kuo et al., 2005) and the precursor polypeptide pomc (Liu et al., 2003; Herzog et al., 2004; Dickmeis et al., 2007; Tessmar-Raible et al., 2007; Manoli and Driever, 2014). At 30 hpf, otpb is detected in the posterior hypothalamus and at the DTJ (Fig. 3G,G′) but by 55 hpf additional otpb+ cells are detected in the tuberal and anterior hypothalamus (Fig. 3H,H′, white arrowheads; see Eaton and Glasgow, 2007) adjacent to the shh+ AR (Fig. 3I). Ventral views show that otpb+ cells in the tuberal and anterior hypothalamus are periventricular, suggesting they are immature neurons (see Fig. 4C″; Herget et al., 2014). ff1b expression is detected at 30 hpf (Fig. 3J,J′), and by 55 hpf is expressed broadly in the tuberal hypothalamus. Sections reveal that ff1b is expressed in shh+ AR cells and adjacent periventricular cells (Fig. 3K-K″). pomc+ cells cannot be detected in the 30 hpf hypothalamus (Fig. 3L,L′) but by 55 hpf are detected in the tuberal hypothalamus (Fig. 3M-M″) rostral to rx3+ progenitors (Fig. 3N, white arrowheads). Together, our data show that anterior elongation correlates with the development and growth of the shh+rx3− AR and with the differentiation of otpb+, ff1b+ and pomc+ cells in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus (schematized in Fig. 3O,P).

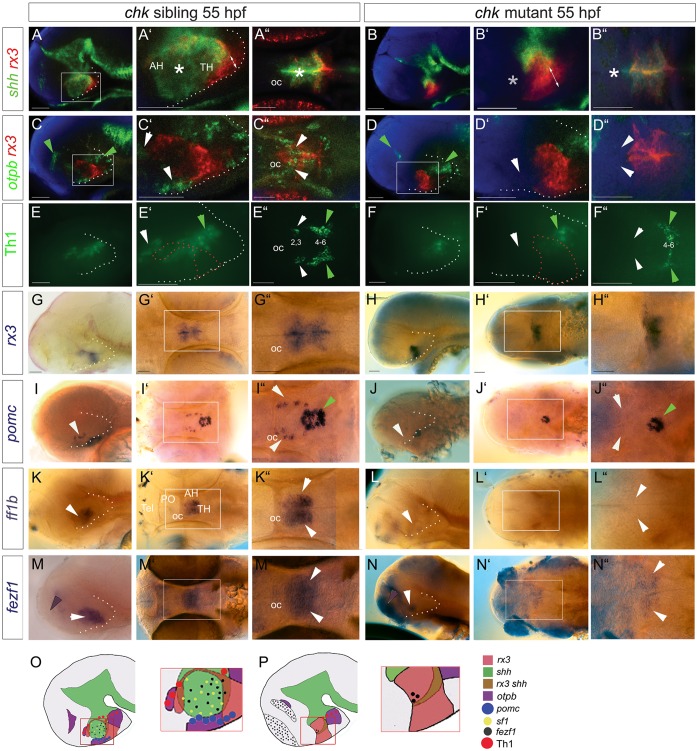

Fig. 4.

Rx3 is required for shh+ AR and anterior/tuberal differentiation. (A-N) Side or ventral views of 55 hpf chk sibling or mutant embryos. Asterisks in A′,A″ show shh+ AR, which is absent in the chk mutant (B′B″, asterisks). White arrowheads point to otpb+ tuberal/anterior cells (C′,C″), Group2/3 Th1+ anterior cells (E′,E″), pomc+ cells (I,I″), ff1b+ cells (K,K″), all of which are absent in chk mutants (D′,D″,F′,F″,J,J″,L,L″,N,N″), and to fezf1+ progenitors (M,M″), which are reduced in the chk mutant (N,N″). Green arrowheads point to expression domains unaffected in chk mutants. Purple arrowheads point to fezf1 domain, upregulated in chk mutants. White and red dotted lines as in Fig. 2. (O,P) Schematics depicting expression patterns; boxed regions show areas shown in high-power views. AH, anterior hypothalamus; oc, optic commissure; PO, preoptic hypothalamus; Tel, telencephalon; TH; tuberal hypothalamus. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Rx3 is required for shh+ AR and neuronal differentiation

We next addressed the requirement for Rx3 in development of the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus. Previous studies have shown that pomc+ and avp+ neurons are absent in embryos lacking rx3 (Dickmeis et al., 2007; Tessmar-Raible et al., 2007) but a more extensive characterization of other progenitor/differentiating cells has not yet been performed.

Analysis of 55 hpf chk embryos shows that the shh+ AR fails to develop in chk mutants (Fig. 4A-B″, white asterisks; note that posterior shh expression in the floor plate and basal plate appears to be unaltered). rx3 expression itself is markedly different in chk mutant embryos compared with siblings: zones I-III cannot be clearly resolved (Fig. 4A′,B′,G-H″).

The failure in development of the shh+ AR correlates with a failure in differentiation. Mutant embryos lack otpb+ cells in both the tuberal and anterior hypothalamus [Fig. 4C-D″, white arrowheads; note that otpb+ cells in the posterior hypothalamus and at the DTJ (green arrowheads) appear to be unaffected]. Previous studies suggest that the anterior otpb+ progenitors give rise to Group 2/3 Tyrosine hydroxylase (Th) dopaminergic neurons (Löhr et al., 2009); in keeping with this, mutant embryos lack Group 2/3 Th1+ neurons (Fig. 4E-F″, white arrowheads: note Group 4-6 Th1+ neurons are not eliminated). rx3 mutant embryos additionally lack pomc+ cells (Fig. 4I-J″, white arrowheads) and ff1b+ cells (Fig. 4K-L″, white arrowheads) in the tuberal hypothalamus [note pomc+ cells in the adenohypophysis (green arrowheads) are still detected]. Finally, fezf1, a homeodomain (HD) gene that in mouse is regulated by Sf1 (Kurrasch et al., 2007) and in fish regulates otpb (Blechman et al., 2007), is markedly reduced (Fig. 4M-N″, white arrowheads); at the same time, ectopic expression is detected in the telencephalon. rx3 morphant embryos closely phenocopy chk mutants (Figs S2, S3; Fig. 6G,G′; Fig. 7N-R). Together, these analyses show that Rx3 is required for establishment of the shh+rx3− AR and for the differentiation of tuberal/anterior cells (Fig. 4O,P).

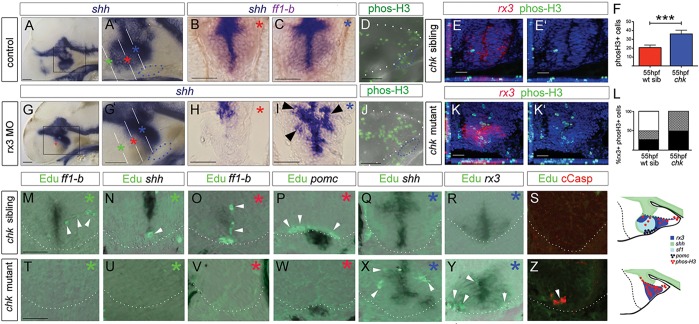

Fig. 6.

Rx3 promotes progenitor survival and growth. (A-C,G-I) Whole-mount side views (A,G) or sections (B,C,H,I: planes and positions indicated by coloured asterisks) through 55 hpf control or rx3 morphant embryos. A′,G′ show high-power views of boxed regions in A,G. Arrowheads in I show disorganized shh+ cells around 3V. (D,J) Whole-mount side views of phosH3 in 55 hpf control or rx3 morphant embryo. (E,E′,K,K′) Representative sections after phosH3/rx3 co-labelling in 55 hpf chk sibling or mutant embryos. E′,K′ show single-channel views. (F,L) Quantitative analyses. (F) Numbers of phosH3+ cells in chk mutant or sibling embryos (n=6 each). Significantly more phosH3+ cells are detected in mutants compared with siblings (P<0.001). (L) Proportion of phosH3+ cells that are rx3+ (black), adjacent to (hatched) or distant from (white) rx3+ cells in mutant versus sibling chk embryos. (M-R,T-Y) Representative serial sections, from rostral to caudal (coloured asterisks denote approximate position of each section, see A′,G′) of a 55 hpf chk sibling (M-R) or mutant (T-Y) embryo. White arrowheads point to EdU+ cells. (S,Z) Representative sections of 35 hpf chk sibling or mutant embryos. 18±2 cCasp+ cells detected in chk mutants, n=8 embryos. Schematics summarize expression patterns in mutant versus sibling chk embryos. White and blue dotted lines as in Fig. 2. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Fig. 7.

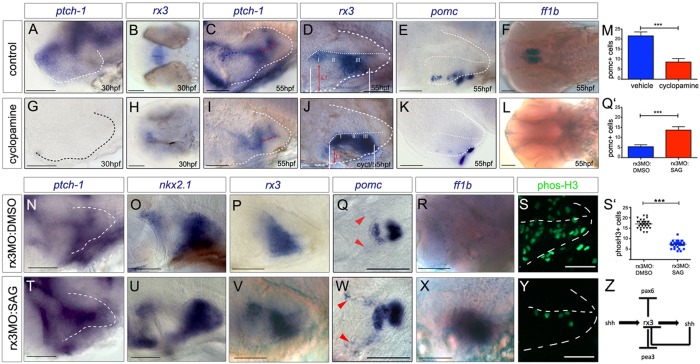

Shh signalling functions as an rx3 ‘on-off’ switch. (A-L) Side or ventral views of 30 hpf and 55 hpf wild-type embryos, exposed to vehicle or cyclopamine over 10-28 hpf (A,B,G,H) or over 28-55 hpf (C-F,I-L). Red arrows and white bars in D,J show distances measured for width and length of tuberal/anterior hypothalamus. (M) Quantitative analysis: significantly fewer pomc+ cells are detected after cyclopamine exposure (***P<0.0001, n=30 embryos). (N-Y) Side or ventral views of 55 hpf rx3 morphant embryos, exposed to DMSO vehicle (N-S) or SAG (T-Y) from 28 hpf. (Q′,S′) Quantitative analysis. Significantly more pomc+ cells (Q'; ***P<0.0001, n=30 embryos) and significantly fewer phosH3+ cells (S'; ***P<0.0001, n=27 embryos) are detected after late SAG rescue. (Z) Model for anterior/tuberal progenitor development. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Rx3 represses dorsal and ventro-tuberal progenitors

We postulated that, as in mouse (Lu et al., 2013), Rx3 may switch the identity of other progenitor domains to select posterior tuberal/anterior progenitor fates, and that the absence of Rx3 will lead to alterations in progenitor domains/increased alternative fates.

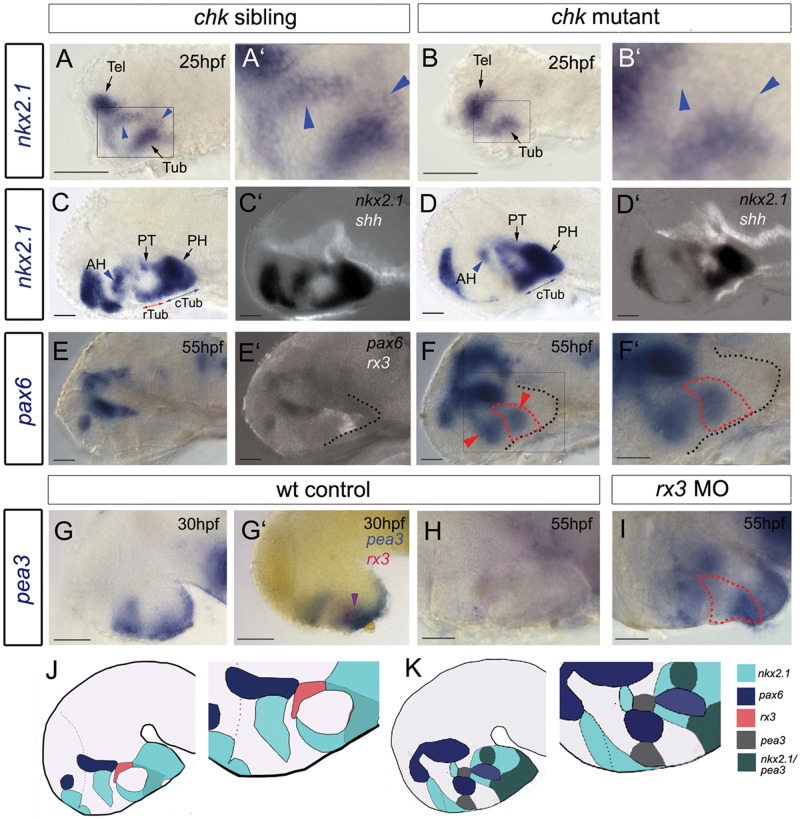

The transcription factor nkx2.1 (previously known as nkx2.1a; Manoli and Driever, 2014), the homologue of which in mouse is required for tuberal neuronal differentiation (Correa et al., 2015; Kimura et al., 1996; Yee et al., 2009), shows subtle differences in expression in chk mutants at 25 hpf: two sets of nkx2.1+ cells in the forming tuberal/anterior hypothalamus (Fig. 5A,A′, blue arrowheads) cannot be detected (Fig. 5B,B′). By 55 hpf, this difference is pronounced: nkx2.1 is reduced in the anterior hypothalamus and is not detected in the rostral tuberal hypothalamus [Fig. 5C,D; position of tuberal/anterior hypothalamus confirmed through double-labelling with shh (Fig. 5C′,D′)]. nkx2.1 in the caudal tuberal, posterior hypothalamus and posterior tuberculum appears to be unchanged.

Fig. 5.

Rx3 suppresses dorsal and ventro-tuberal progenitors. (A-I) Side views of control embryos or embryos in which rx3 is absent. A′,B′,F′ show high-power views of boxed regions in A,B,F. Blue arrowheads and red arrows in A-D point to nkx2.1+ cells, which are absent in chk mutants. Blue arrows in C,D point to nkx2.1+ ventral-tuberal domain. Red arrowheads in F point to ectopic pax6+ cells. Black dotted lines indicate outline of ventral hypothalamus. Red dotted lines as in Fig. 2. Purple arrowhead in G′ points to rx3+pea3+ cells. H,I show views of isolated neuroectoderm. (J,K) Schematics of expression patterns in chk sibling (J) or mutant (K) 55 hpf embryos. White and red dotted lines as in Fig. 2 AH, anterior hypothalamus; PH, posterior hypothalamus; PT, posterior tuberculum; Tel, telencephalon; (c)(r)Tub, (caudal) (rostral) tuberal hypothalamus. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Previous studies show that Nkx and Pax6 transcription factors exert cross-repressive interactions in the hypothalamus (Manoli and Driever, 2014), prompting us to examine expression of pax6. In control embryos, pax6 is confined to the thalamus/dorsal hypothalamus and abuts the dorsal-most boundary of rx3 (Fig. 5E,E′). In the absence of Rx3, pax6 is detected ectopically in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus within and rostral to rx3+ cells (Fig. 5F, red arrowheads; Fig. S2). Thus, the absence of Rx3 leads to a ventral expansion of pax6+ progenitors.

Ectopic pax6+ domains do not extend throughout rx3 zone III (Fig. 5F, red dotted outline) raising the question of whether other progenitors are also affected by loss of Rx3. The ets transcription factor pea3 (etv4) is expressed in the hypothalamus at 30 hpf, and overlaps with rx3 zone III cells (Fig. 5G,G′). pea3 is downregulated at 55 hpf in control embryos but expression persists in chk mutants (Fig. 5H,I). These results suggest that Rx3 normally suppresses both dorsal pax6+ and ventro-tuberal pea3+ progenitors (Fig. 5J,K schematics) and predicts a widespread change in the profile of other progenitor markers in chk mutants. In support of this idea, ascl1a and sox3 are not downregulated in zone II in chk mutant embryos, in contrast to their appearance in controls (Fig. S4A-H, white arrowheads).

In mouse, conditional ablation of Rx leads to a failure to select arcuate/VMN fates and, instead, additional Dlx2+ DMN cells form (Lu et al., 2013). To determine whether the increase in pea3 and pax6 expression results in an increase in ventro-tuberal and DMN-like cells, respectively, we examined the neurohypophyseal marker fgf3 and the DMN marker dlx1 (dlx1a). Both show slightly stronger expression in chk mutants (Fig.S4E-H). and the ventro-tuberal hypothalamus appears longer in chk mutants (Fig. S4A,C) suggesting that in the absence of Rx3, there is some expansion of ventral-tuberal and dorsal progenitors and their derivatives.

Rx3 is required for progenitor survival and anisotropic growth

The increase in fgf3 and dlx1 in chk mutants is, however, mild, suggesting that Rx3 may play a role other than switching progenitor fates. In sectioned embryos we had noticed an unusually disorganized accumulation of shh+ cells (Fig. 6A-C,G-I) suggesting that some ectopic progenitors may accumulate in the recess walls, rather than grow and progress to normal fates.

To examine this further, we compared proliferation and fate in control and rx3-null embryos. In comparison to controls, rx3-morphant and chk mutant embryos showed significantly more phosH3+ cells in the 55 hpf embryo (Fig. 6D-F,J-K′) that, in contrast to controls, were largely rx3+ or adjacent to rx3+ cells (Fig. 6L). To determine more specifically the fate of proliferating progenitors, we pulsed 30 hpf fish with EdU, chased to 55 hpf and, on serial adjacent sections, analysed whether EdU+ cells progressed to periventricular cells in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus, were retained as rx3+ or shh+ progenitors, or assumed other fates. In chk siblings, the majority (63%; n=156 cells, 6 embryos) of EdU+ cells were laterally oriented chains in the anterior (Fig. 6M) or tuberal (Fig. 6P) hypothalamus and were detected in or in the vicinity of ff1b+ and pomc+ cells (Fig. 6M,O,P). A minority (27%) were shh+rx3− anterior (Fig. 6N,O) or lateral (not shown) recess tip cells. No EdU+ rx3+ cells were detected in zones I or III (Fig. 6R; data not shown). By contrast, in chk mutant embryos, no EdU+ cells were detected in the region rostral to the adenohypophysis, i.e. the region that would form part of the anterior/tuberal hypothalamus (Fig. 6T-W). The majority (76%, n=165 cells, 6 embryos) of EdU labelling was detected in/adjacent to shh+ (Fig. 6X) and rx3+ (Fig. 6Y) cells. EdU+ cells accumulated especially at the recess junctions and tips. No cleaved (c)Caspase+ cells were detected after the 25 h chase period, but after a 5 h chase, cCaspase+ cells, including EdU+cCaspase+ cells were detected in chk mutants (Fig. 6Z). No cCaspase was detected in siblings (Fig. 6S).

These findings, together with our previous observations, suggest that rx3+ progenitors give rise to cells, including shh+ AR tip cells, that grow anisotropically and give rise to anterior/tuberal cells. Additionally, these findings show that in the absence of Rx3 function, many progenitor cells accumulate in the recesses, where they either die, or fail to differentiate. Together, these observations point to a mechanism in which Rx3 selects tuberal/anterior progenitors and governs their survival and growth (Fig. 6 schematics).

Shh is an ‘on-off’ switch for rx3

Our findings demonstrate that Rx3 is upstream of that of shh in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus. However, given the crucial role of Shh in induction and early patterning of the hypothalamus (Bedont et al., 2015; Burbridge et al., 2016; Pearson and Placzek, 2013; Blaess et al., 2015), we wished to test whether at earlier stages of hypothalamic development Shh is upstream of rx3, a possibility suggested by the observation that at epiboly stages, shh is expressed on midline cells, close to the early zone of rx3 expression (Fig. S5A,B).

Ptch1, a Shh-receptor and ligand-dependent antagonist, is weakly detected in the forming tuberal/anterior hypothalamus at 30 hpf (Fig. 7A), but not detected when embryos are exposed to cyclopamine over 10-28 hpf (Fig. 7G). Similar observations were made with ptch2 (not shown). At the same time, cyclopamine treatment results in a marked downregulation of rx3 (Fig. 7B,H) mimicking the phenotype of slow muscle omitted (smu) mutant zebrafish that lack essential components of the Hh pathway (Fig. S5C,D). Together, these results suggest that Shh induces rx3 in the early embryo.

By 55 hpf, strong ptch1 expression is detected in zones I and III (Fig. 7C) with weaker expression in zone II (Fig. 7C). ptch2 expression appears similar (not shown). To determine whether Shh influences rx3 at this stage, we exposed embryos to cyclopamine over 28-55 hpf. This resulted in an effective inhibition of Shh signalling, as judged by ptch1 downregulation (Fig. 7I) but led to a consistent increase in rx3 expression (Fig. 7D,J). Increased rx3 expression was accompanied by changes that appeared to phenocopy loss of rx3, notably a significant decrease in tuberal/anterior territory (Fig. 7D,J white lines and red arrows), a decrease in hypothalamic pomc+ cells (Fig. 7E,K,M), the loss of ff1b expression (Fig. 7F,L), a decrease in Th1+ Group2/3 neurons (Fig. S5E,F; note Groups 4-6 in the posterior hypothalamus are unaffected) and a failure to downregulate sox3 in zone II (not shown). These observations suggest that Shh mediates rx3 downregulation in zone II, and that this is essential for differentiation of tuberal/anterior hypothalamic progenitors.

This idea predicts that provision of Shh may be sufficient to rescue the phenotypic effects of rx3 morphant embryos, once the effects of the morpholino begin to disappear. To test this, we attempted a ‘late rescue’, in which rx3 morphant embryos were exposed to the small molecule Shh agonist SAG over 28-55 hpf. SAG was effective in restoring a normal pattern of Shh signalling in rx3 morphant embryos, as judged by expression of ptch1 (Fig. 7N,T). Furthermore, both the normal pattern of nkx2.1 and the characteristic profile of rx3 in zones I, II and III were restored (Fig. 7O,P,U,V). Both pomc+ and ff1b+ cells were restored in rx3 morphant embryos in response to SAG administration (Fig. 7Q,Q′,R,W,X). Finally, cellular homeostasis was restored: the enhanced numbers of phosH3+ cells in rx3 morphants were reduced to normal, wild-type levels (Fig. 7S,S′,Y). This rescue is not seen when an early SAG-treated regime is used (10-28 hpf; not shown), or in chk mutant embryos treated with SAG over 28-55 hpf (Fig. S6), indicating that functional Rx3 is required for the late rescue. Together, these results suggest that a Shh-rx3 ON and Shh-rx3 OFF feedback loop (Fig. 7Z) is essential for the development of the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that Rx3 function is required for morphogenesis of the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus and governs three aspects of cell behaviour: it re-specifies progenitor types to tuberal/anterior identities, promotes their survival and governs their anisotropic growth/migration. Shh coordinates tuberal/anterior progenitor selection and behaviour by acting as an on-off switch for rx3. Thus, a Shh-Rx3-Shh feed-forward/feedback loop generates tuberal/anterior progenitors that grow to expand the surface area of the third ventricle and diversify the neuronal subtypes that differentiate around it.

Rx3 selects tuberal/anterior hypothalamic progenitors

Our studies confirm that Rx3 function is not required for induction or initial hypothalamic patterning (Kennedy et al., 2004), but show that it is essential to elaborate patterning. Our data suggest that Rx3 autonomously selects nkx2.1+ tuberal/anterior progenitors that grow anisotropically. In chk mutant embryos, pax6a expands ventrally into rx3+ progenitors, a phenotype detected as early as 19 hpf (Loosli et al., 2003). The ventral expansion of pax6a mimics the phenotype of nkx2.1/nkx2.4a/nkx2.4b-null embryos (Manoli and Driever, 2014) and suggests that Rx3 re-specifies progenitors that would otherwise assume a dorsal hypothalamic or pre-thalamic identity.

At the same time, Rx3 represses pea3. In wild-type animals, pea3 overlaps with the ventral-most domain of rx3 expression at 30 hpf, but is downregulated by 55 hpf. In chk mutant fish, pea3 expression persists. Although we have not performed double FISH with pea3 and pax6 in chk mutant fish, their expression patterns appear to be complementary. This suggests that Rx3 operates as a switch in at least two separate progenitor populations and provides a prosaic interpretation for the existence of two domains: the dorsal rx3+shh+ and ventral rx3+shh− domains.

Our studies reveal that Rx3 promotes alternative fates in progenitor cells. Its loss leads to one of three outcomes: to undergo apoptosis or to be retained as a proliferating cell held in the wall of the ventricle (novel outcomes), or to initiate alternative adjacent differentiation programmes – after pulse-chase, some EdU+ cells are detected in periventricular regions in chk mutants where it is likely that they contribute to nkx2.1+pea3+ progenitors and hence fgf-expressing neurohypophysis ventrally, and to dlx1+ cells dorsally. dlx1+ cells are likely to be immature DMN-like neurons and notably, somatostatin+ neurons persist in chk mutants (Dickmeis et al., 2007). Together, our studies suggest that Rx3 selects tuberal/anterior neuronal progenitors and limits both ventro-tuberal neurohypophyseal and DMN-like progenitors.

In addition to promoting cell survival, Rx3 regulates cellular homeostasis in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus, orchestrating a balance of proliferation and differentiation. We surmise that the increased proliferation seen in the absence of Rx3 reflects changes in Wnt or Fibroblast growth factor signalling, both of which are upregulated in chk mutants (Stigloher et al., 2006; Yin et al., 2014; this study). fgf3, in particular, normally abuts neuroepithelial-like rx3+shh− cells in both zones I and III and is upregulated in rx3 mutants. Potentially, the driving force for proliferation resides in rx3+shh− cells in zones I and III that progress to rx3+shh+ cells in zone II.

Previous reports have shown that Rx3 is required for retinal fate selection and that telencephalic fates are expanded in its absence (Bielen and Houart, 2012; Cavodeassi et al., 2013). Our studies likewise show changes in the telencephalon/eye territory: fezf1 is upregulated in rx3 mutants, and both shh and nkx2.1 in the telencephalon/tuberal/anterior area are greatly reduced. Together, these studies suggest that Rx3 selects fate in cells of distinct origins: anterior telencephalic and posterior diencephalic. Importantly, not all hypothalamic cells alter their identity in the absence of Rx3: the posterior hypothalamus expresses nkx2.1, shh and otpb as normal, the rostral-most hypothalamus expresses otpb and nkx2.1 and the tuberal hypothalamus expresses nkx2.1, pea3 and fgf3, emphasising the fact that Rx3 elaborates, rather than initiates, hypothalamic patterning.

Shh is an on-off switch for rx3

Our study shows that Shh is required for both the induction of rx3 and the progression of rx3+ to rx3−shh+ progenitors and demonstrates that both steps are required for tuberal/anterior hypothalamic neurogenesis. Downregulation of Shh signalling over 10-30 hpf leads to an almost complete loss of rx3 expression. By contrast, downregulation over 30-55 hpf leads to sustained rx3 in zone II and a phenotype that is highly similar to that of chk mutants: sox3 is not downregulated in zone II, the shh+rx3− AR does not form, the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus is short and its resident neurons do not differentiate. Importantly, the Shh agonist SAG can restore normal patterns of proliferating progenitors and neuronal differentiation in late rx3 morphants. The most likely interpretation of these findings is that Shh-mediated rx3 upregulation is required to select tuberal/anterior progenitors but that Shh-mediated rx3 inhibition is required for these to realise their differentiation programme(s). Future studies are needed to establish whether the downregulation of sox3, nkx2.1, ascl1 and ptch1 that we observe in wild-type but not chk mutant fish are similarly required for progression of tuberal/anterior progenitors. We predict that the downregulation of ptch1, in particular, supports Shh active signalling from zone II cells and contributes to development of the shh+ AR. The intricate regulation of induction and cessation of Shh signalling in sets of neighbouring cells is emerging as a common theme within the CNS (Briscoe and Therond, 2013) and provides the opportunity to drive expansion of territories and build increasingly complex arrays of neurons.

In summary, our studies suggest that Shh plays a dual role in rx3 regulation, inducing, then repressing it, and are consistent with a model in which Shh deriving from AR cells, feeds back to rx3+ progenitors to promote their further differentiation.

Origins of hypothalamic neurons

Our studies show that the zebrafish tuberal hypothalamus includes regions analogous to the mouse Arc and VMN. Our EdU pulse-labelling studies suggest that shh+ AR cells and differentiating ff1b+ and pomc+ neurons derive from rx3+ cells. After a 25 h chase, we detect strings of EdU+ cells, presumably of clonal origin, extending medio-laterally from the shh+ AR tips to pomc+ and ff1b+ regions, favouring the idea that forming neurons derive from rx3+shh+ progenitors via rx3−shh+ progenitors. In mouse, Rax+ cells give rise to Pomc+ and Sf1+ neurons (Liu et al., 2013). Other mouse studies show that Shh+ hypothalamic cells give rise to tuberal neurons (Alvarez-Bolado et al., 2012), and that Shh ablation in hypothalamic cells leads to the loss of Pomc and Sf1 (Shimogori et al., 2010) and a reduction in hypothalamic territory (Alvarez-Bolado et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2012). These studies, together with observations that loss of Nkx2.1 results in loss of tuberal hypothalamic neurons (Correa et al., 2015; Kimura et al., 1996; Yee et al., 2009), disruptions to the infundibulum and a reduction in the size of the third ventricle (Kimura et al., 1996) suggests a conserved differentiation route of pomc and ff1b/sf1 immature neurons and the tuberal hypothalamus from zebrafish to mouse.

In zone I, rx3 is expressed in the anterior hypothalamus, in a region that may be equivalent to the anterior-dorsal domain reported in mouse (Shimogori et al., 2010). Our work, together with previous studies, suggests that here, Rx3 plays a role in a conserved differentiation pathway for avp+ and Group2/3 Th1+ neurons. avp+ and Group 2/3 Th1+ neurons localize within a discrete subregion of hypothalamic otp expression (Löhr et al., 2009; Herget et al., 2014; Herget and Ryu, 2015) and in fish, as in mouse, otp genes are required for the differentiation of neurons that express avp and Th (Acampora et al., 1999; Löhr et al., 2009; Fernandes et al., 2013). avp+ neurons fail to differentiate in the absence of rx3 (Tessmar-Raible et al., 2007) and we now show a specific loss of an otpb+ subset and Group 2/3 Th1+ neurons. This suggests that Rx3 governs a subset of otpb+ progenitors in the anterior hypothalamus that will give rise to avp+ and Group 2/3 Th1+ neurons. We have not yet investigated whether this otpb+ progenitor subset are dependent on Shh. However, in mouse, conditional deletion of hypothalamic Shh leads to a reduction in Otp expression and Avp+ neurons (Szabo et al., 2009) as well as a loss of Sim1 in the PVN (Shimogori et al., 2010), suggesting that the Shh-Rx3-Shh pathway that governs pomc+ and ff1b+ cell fates may likewise govern avp+ and Group 2/3 Th1+ fates. A previous study has highlighted Sim1 and Otp as core components of a conserved transcriptional network that specifies neuroendocrine as well as A11-related hypothalamic dopaminergic neurons (Löhr et al., 2009), suggesting that Rx3 may be intimately linked to this pathway. Notably, because other NPO neurons, including oxytocin+ (previously known as isotocin) neurons are not affected by loss of Rx3, our data suggest that neurons that make up the NPO derive from discrete lineages. Our work adds to a growing body of evidence that directed cell migrations play a pivotal role in ventral forebrain/hypothalamic morphogenesis (Varga et al., 1999; Cavodeassi et al., 2013 and see Pearson and Placzek, 2013). We do not know the mechanisms that operate downstream of Rx3 to govern appropriate migration, but Eph/Ephrin signalling, expression of Fgf and Netrin, all of which govern cell adhesion and migration of neural cells, are disrupted in chk mutant embryos (Cavodeassi et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2014; this study) and could contribute.

In conclusion, our study suggests a mechanism by which Shh elaborates patterning in the hypothalamus. Previous reports suggest that Shh patterns the early hypothalamus in many vertebrates, establishing early progenitor domains (reviewed by Pearson and Placzek, 2013; Blaess et al., 2015). Our study shows that in zebrafish, Shh elaborates early patterning by switching progenitor domain identity, and promoting the survival and anisotropic growth of the new progenitor cells. Recent studies in the developing spinal cord show that the coordination of growth and specification can elaborate patterning in an expanding tissue, if molecularly distinct neural progenitor domains undergo differential rates of differentiation (Kicheva et al., 2014), raising the possibility that Shh may govern differentiation rates in the tuberal/anterior hypothalamus. Studies in mice that reveal similarities in the phenotypes of embryos in which Shh or Rax are conditionally ablated raise the possibility that features of the mechanism that we describe here may be conserved in other vertebrates.

Finally, the Shh-Rx3-Shh loop that we describe provides a means to maintain a dynamic balance between proliferating and differentiating cells. Studies in mice show that at least a subset of Rax+ cells persist into adulthood as stem cells (Miranda-Angulo et al., 2014) that can direct hypothalamic neurogenesis even in postnatal life. The exquisite regulation of Shh, Fgf and Wnt signalling, via Rx3, is likely to hold the key to a better understanding of hypothalamic neurogenesis throughout life and support a better understanding of complex human pathological conditions and dysfunctional behaviours that are underlain by tuberal/anterior hypothalamic cells and circuits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Zebrafish were staged according to Kimmel et al. (1995). chkw29 fish were kindly provided by Dr Breandan Kennedy (University College Dublin, Ireland).

Nomenclature

We use the terms preoptic, anterior, tuberal and posterior to define the rostro-caudal domains of the hypothalamus. The region we define as anterior may overlap with the region that is conventionally termed the NPO (see Discussion).

In situ hybridization

Single and double in situ hybridization methods were adapted from Thisse and Thisse (2008) and Lauter et al. (2011) (details in supplementary Materials and Methods). Embryos were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and visualized by Olympus Nomarski or confocal microscopy. For cryostat sectioning, embryos were re-fixed and equilibrated in 30% sucrose, and 15-µm-thick serial adjacent sections cut. n=10-40 embryos for whole mounts; n=4-6 embryos for sections.

EdU analysis

Embryos were pulsed with 300 μM EdU for 1 h on ice, chased for 1, 5 or 25 h, then processed for cryostat sectioning and double EdU/in situ hybridization analysis (details in supplementary Materials and Methods) using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Fisher Scientific).

Immunohistochemistry

Anti-phosH3 (06-570, Millipore), anti-cleaved Caspase (9661, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-Th1 (22941, Immunostar) were used at 1:1000. Fixed embryos or sections were processed according to Liu et al. (2013) and mounted in VectaShield.

Length measurements

Length was determined through measurements of images, where in situ patterns could be detected relative to morphological landmarks (diencephalic-telencephalic junction, optic commissure, lateral ventricle, posterior hypothalamus and adenohypophysis). For each experiment, length was normalized to the average length of age-matched sibling controls.

Cell quantification

phosH3+ and EdU+ cell numbers were obtained through counts in serial adjacent sections through individual hypothalami using in situ patterns against morphological landmarks (above) to determine relative position. For chk mutants, section position was determined relative to unaffected posterior hypothalamus.

Image acquisition

Differential interference contrast or fluorescence images were acquired using Olympus BX60 Zeiss Confocal LSM510 Meta or Olympus Confocal microscopes. Data was processed with Adobe Photoshop CS3/Adobe Illustrator CS.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5. Each data value sampled was tested for Gaussian distribution prior to unpaired t-test by performing baseline subtraction of the two datasets and analysed using the D'Agostino–Pearson omnibus normality test.

Cyclopamine treatment

Cyclopamine (in ethanol) was used at 50 µM, optimised on the basis of ptch1 downregulation (20, 50, 100, 120 μM tested). Cyclopamine or ethanol were added to dechorionated embryos, which were kept in the dark.

SAG treatment

SAG (Millipore-EMD chemicals) in DMSO was used at 10 µM, optimised on basis of ptch1 upregulation (2, 5, 8, 10 μM tested). SAG or DMSO was added to de-chorionated embryos in E3 medium, and embryos were kept in the dark.

Morpholino

Morpholinos [0.25 mM rx3 ATG (targets TSS) and 0.15 mM rx3 E212 (targets splice site)] (GeneTools, LLC) (Tessmar-Raible et al., 2007) were injected into one-cell embryos and morphants were selected on the basis of absent eyes.

Note added in proof

Since acceptance of this paper, a paper by Orquera et al. (2016) suggests that in mouse, Rax governs similar mechanisms to those we describe here.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tanya Whitfield, Freek van Eeden and Vincent Cunliffe for help and advice on zebrafish experiments, and James Briscoe and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. We thank Breandan Kennedy for providing chk embryos and help in interrogating RNASeq data.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Experiments were performed and analysed by V.M., H.E., P.E, S.B. and M.P. Concepts/approaches were developed by V.M. and M.P. Manuscript was prepared/edited by V.M., S.B. and M.P.

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) UK [G0401310 and G0802527 to M.P.]. The Bateson Centre zebrafish facility was supported by the MRC [G0400100, G0700091, GO8o2527, G0801680]. Deposited in PMC for immediate release.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.138305.supplemental

References

- Acampora D., Postiglione M. P., Avantaggiato V., Di Bonito M., Vaccarino F. M., Michaud J. and Simeone A. (1999). Progressive impairment of developing neuroendocrine cell lineages in the hypothalamus of mice lacking the Orthopedia gene. Genes Dev. 13, 2787-2800. 10.1101/gad.13.21.2787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Bolado G., Paul F. A. and Blaess S. (2012). Sonic hedgehog lineage in the mouse hypothalamus: from progenitor domains to hypothalamic regions. Neural Dev. 20, 7-4 10.1186/1749-8104-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amat P., Amat-Peral G., Pastor F. E., Blazquez J. L., Pelaez B., Alvarez-Morujo A., Toranzo D. and Sanchez A. (1992). Morphologic substrates of the ventricular route of secretion and transport of substances in the tubero-infundibular region of the hypothalamus. Ultrastructural study. Bol. Asoc. Med. P. R. 84, 56-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. J., El-Hodiri H., Zhang L., Shah R., Mathers P. H. and Jamrich M. (2004). Regulation of vertebrate eye development by Rx genes. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 761-770. 10.1387/ijdb.041878tb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedont J. L., Newman E. A. and Blackshaw S. (2015). Patterning, specification and differentiation in the developing hypothalamus. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 4, 445-468. 10.1002/wdev.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielen H. and Houart C. (2012). BMP signaling protects telencephalic fate by repressing eye identity and its Cxcr4-dependent morphogenesis. Dev. Cell 23, 812-822. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biran J., Tahor M., Wircer E. and Levkowitz G. (2015). Role of developmental factors in hypothalamic function. Front. Neuroanat. 9, 47 10.3389/fnana.2015.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaess S., Szabó N., Haddad-Tóvolli R., Zhou X. and Álvarez-Bolado G. (2015). Sonic hedgehog signaling in the development of the mouse hypothalamus. Front. Neuroanat. 8, 156 10.3389/fnana.2014.00156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blechman J., Borodovsky N., Eisenberg M., Nabel-Rosen H., Grimm J. and Levkowitz G. (2007). Specification of hypothalamic neurons by dual regulation of the homeodomain protein Orthopedia. Development 134, 4417-4426. 10.1242/dev.011262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco A., Bureau C., Affaticati P., Gaspar P., Bally-Cuif L. and Lillesaar C. (2013). Development of hypothalamic serotoninergic neurons requires Fgf signalling via the ETS-domain transcription factor Etv5b. Development 140, 372-384. 10.1242/dev.089094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J. and Thérond P. P. (2013). The mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 416-429. 10.1038/nrm3598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbridge S., Stewart I. and Placzek M. (2016). Development of the neuroendocrine hypothalamus . J. Comp. Physiol. 6, 623-643. 10.1002/cphy.c150023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavodeassi F., Ivanovitch K. and Wilson S. W. (2013). Eph/Ephrin signalling maintains eye field segregation from adjacent neural plate territories during forebrain morphogenesis. Development 140, 4193-4202. 10.1242/dev.097048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang J. C., Mathers P. H. and Raymond P. A. (1999). Expression of three Rx homeobox genes in embryonic and adult zebrafish. Mech. Dev. 84, 195-198. 10.1016/S0925-4773(99)00077-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa S. M., Newstrom D. W., Warne J. P., Flandin P., Cheung C., Lin-Moore A.T., Pierce A. A., Xu A. W., Rubenstein J. L. and Ingraham H. A. (2015). An estrogen-responsive module in the ventromedial hypothalamus selectively drives sex-specific activity in females. Cell Rep. 10, 62-74. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickmeis T., Lahiri K., Nica G., Vallone D., Santoriello C., Neumann C. J., Hammerschmidt M. and Foulkes N. S. (2007). Glucocorticoids play a key role in circadian cell cycle rhythms. PLoS Biol. 5, e78 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton J. L. and Glasgow E. (2007). Zebrafish orthopedia (otp) is required for isotocin cell development. Dev. Genes Evol. 217, 149-158. 10.1007/s00427-006-0123-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes A. M., Beddows E., Filippi A. and Driever W. (2013). Orthopedia transcription factor otpa and otpb paralogous genes function during dopaminergic and neuroendocrine cell specification in larval zebrafish. PLoS ONE 8, e75002 10.1371/journal.pone.0075002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T., Kozak C. A. and Cepko C. L. (1997). rax, a novel paired-type homeobox gene, shows expression in the anterior neural fold and developing retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 3088-3093. 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herget U. and Ryu S. (2015). Coexpression analysis of nine neuropeptides in the neurosecretory preoptic area of larval zebrafish. Front. Neuroanat. 9, 2 10.3389/fnana.2015.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herget U., Wolf A., Wullimann M. F. and Ryu S. (2014). Molecular neuroanatomy and chemoarchitecture of the neurosecretory tuberal/preoptic-hypothalamic area in zebrafish larvae. J. Comp. Neurol. 522, 1542-1564. 10.1002/cne.23480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog W., Sonntag C., von der Hardt S., Roehl H. H., Varga Z. M. and Hammerschmidt M. (2004). Fgf3 signaling from the ventral diencephalon is required for early specification and subsequent survival of the zebrafish adenohypophysis. Development 131, 3681-3692. 10.1242/dev.01235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsimali M., Caneparo L., Houart C. and Wilson S. W. (2004). Inhibition of Wnt/Axin/beta-catenin pathway activity promotes ventral CNS midline tissue to adopt hypothalamic rather than floorplate identity. Development 131, 5923-5933. 10.1242/dev.01453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy B. N., Stearns G. W., Smyth V. A., Ramamurthy V., van Eeden F., Ankoudinova I., Raible D., Hurley J. B. and Brockerhoff S. E. (2004). Zebrafish rx3 and mab21l2 are required during eye morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 270, 336-349. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kicheva A., Bollenbach T., Ribeiro A., Valle H. P., Lovell-Badge R., Episkopou V. and Briscoe J. (2014). Coordination of progenitor specification and growth in mouse and chick spinal cord. Science 345, 1254927 10.1126/science.1254927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B. and Schilling T. F. (1995). Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253-310. 10.1002/aja.1002030302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S., Hara Y., Pineau T., Fernandez-Salguero P., Fox C. H., Ward J. M. and Gonzalez F. J. (1996). The T/ebp null mouse: thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein is essential for the organogenesis of the thyroid, lung, ventral forebrain and pituitary . Genes Dev. 10, 60-69. 10.1101/gad.10.1.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M.-W., Postlethwait J., Lee W.-C., Lou S.-W., Chan W.-K. and Chung B.-C. (2005). Gene duplication, gene loss and evolution of expression domains in the vertebrate nuclear receptor NR5A (Ftz-F1) family. Biochem. J. 389, 19-26. 10.1042/BJ20050005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurrasch D. M., Cheung C. C., Lee F. Y., Tran P. V., Hata K. and Ingraham H. A. (2007). The neonatal ventromedial hypothalamus transcriptome reveals novel markers with spatially distinct patterning . J. Neurosci. 27, 13624-13634. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2858-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauter G., Söll I. and Hauptmann G. (2011). Multicolor fluorescent in situ hybridization to define abutting and overlapping gene expression in the embryonic zebrafish brain. Neural Dev. 6, 10 10.1186/1749-8104-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. E., Wu S.-F., Goering L. M. and Dorsky R. I. (2006). Canonical Wnt signaling through Lef1 is required for hypothalamic neurogenesis. Development 133, 4451-4461. 10.1242/dev.02613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N.-A., Hunag H., Herzog W. Hammerschmidt M., Lin S. and Melmed S. (2003). Pituitary corticotroph ontogeny and regulation in transgenic zebrafish. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 959-966. 10.1210/me.2002-0392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Pogoda H.-M., Pearson C. A., Ohyama K., Lohr H., Hammerschmidt M. and Placzek M. (2013). Direct and indirect roles of Fgf3 and Fgf10 in innervation and vascularisation of the vertebrate hypothalamic neurohypophysis. Development 140, 1111-1122. 10.1242/dev.080226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhr H. and Hammerschmidt M. (2011). Zebrafish in endocrine systems: recent advances and implications for human disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 73, 183-211. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhr H., Ryu S. and Driever W. (2009). Zebrafish diencephalic A11-related dopaminergic neurons share a conserved transcriptional network with neuroendocrine lineages. Development 136, 1007-1017. 10.1242/dev.033878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loosli F., Staub W., Finger-Baier K. C., Ober E. A., Verkade H., Wittbrodt J. and Baier H. (2003). Loss of eyes in zebrafish caused by mutation of chokh/rx3. EMBO Rep. 4, 894-899. 10.1038/sj.embor.embor919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Kar D., Gruenig N., Zhang Z. W., Cousins N., Rodgers H. M., Swindell E. C., Jamrich M., Schuurmans C., Mathers P. H. et al. (2013). Rax is a selector gene for mediobasal hypothalamic cell types. J. Neurosci. 33, 259-272. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0913-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machluf Y., Gutnick A. and Levkowitz G. (2011). Development of the zebrafish hypothalamus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1220, 93-105. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoli M. and Driever W. (2014). nkx2.1 and nkx2.4 genes function partially redundant during development of the zebrafish hypothalamus, preoptic region and pallidum. Front. Neuroanat. 8, 145 10.3389/fnana.2014.00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers P. H., Grinberg A., Mahon K. A. and Jamrich M. (1997). The Rx homeobox gene is essential for vertebrate eye development. Nature 387, 603-607. 10.1038/42475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu J., Barth A., Rosa F. M., Wilson S. W. and Peyrieras N. (2002). Distinct and cooperative roles for Nodal and Hedgehog signals during hypothalamic development. Development 129, 3055-3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Martinez O., Amaya-Manzanares F., Liu C., Mendoza M., Shah R., Zhang L., Behringer R. R., Mahon K. A. and Jamrich M. (2009). Cell-autonomous requirement for rx function in the mammalian retina and posterior pituitary. PLoS ONE 4, e4513 10.1371/journal.pone.0004513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Angulo A. L., Byerly M. S., Mesa J., Wang H. and Blackshaw S. (2014). Rax regulates hypothalamic tanycyte differentiation and barrier function in mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 522, 876-899. 10.1002/cne.23451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranishi Y., Terada K. and Furukawa T. (2012). An essential role for Rax in retina and neuroendocrine system development. Dev. Growth Differ. 54, 341-348. (This is a review) 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rahilly R. and Müller F. (1990). Ventricular system and choroid plexuses of the human brain during the embryonic period proper. Am. J. Anat. 189, 285-302. 10.1002/aja.1001890402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orquera D. P., Nasif S., Low M. J., Rubinstein M. and de Souza F. S. (2016). Essential function of the transcription factor Rax in the early patterning of the mammalian hypothalamus. Dev. Biol. S0012-1606(16)30008-2. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak T., Yoo S., Miranda-Angulo A. M., Wang H. and Blackshaw S. (2014). Rax-CreERT2 knock-in mice: a tool for selective and conditional gene deletion in progenitor cells and radial glia of the retina and hypothalamus. PLoS ONE 9, e90381 10.1371/journal.pone.0090381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C. A. and Placzek M. (2013). Development of the medial hypothalamus: forming a functional hypothalamic-neurohypophyseal interface. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 106, 49-88. 10.1016/B978-0-12-416021-7.00002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puelles L., Martinez-de-la-Torre M., Bardet S. and Rubenstein J. L. R. (2012). Hypothalamus. In The Mouse Nervous System (ed. C. Watson, G. Paxinos and L. Puelles, pp. 221-312. London: Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-369497-3.10008-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rembold M., Loosli F., Adams R. J. and Wittbrodt J. (2006). Individual cell migration serves as the driving force for optic vesicle evagination. Science 313, 1130-1134. 10.1126/science.1127144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimogori T., Lee D. A., Miranda-Angulo A., Yang Y., Wang H., Jiang L., Yoshida A. C., Kataoka A., Mashiko H., Avetisyan M. et al. (2010). A genomic atlas of mouse hypothalamic development. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 767-775. 10.1038/nn.2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stigloher C., Ninkovic J., Laplante M., Geling A., Tannhäuser B., Topp S., Kikuta H., Becker T. S., Houart C. and Bally-Cuif L. (2006). Segregation of telencephalic and eye-field identities inside the zebrafish forebrain territory is controlled by Rx3. Development 133, 2925-2935. 10.1242/dev.02450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo N.-E., Zhao T., Zhou X. and Alvarez-Bolado G. (2009). The role of Sonic hedgehog of neural origin in thalamic differentiation in the mouse. J. Neurosci. 29, 2453-2466. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4524-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessmar-Raible K., Raible F., Christodoulou F., Guy K., Rembold M., Hausen H. and Arendt D. (2007). Conserved sensory-neurosecretory cell types in annelid and fish forebrain: insights into hypothalamus evolution. Cell 129, 1389-1400. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C. and Thisse B. (2008). High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 3, 59-69. 10.1038/nprot.2007.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga Z. M., Wegner J. and Westerfield M. (1999). Anterior movement of ventral diencephalic precursors separates the primordial eye field in the neural plate and requires cyclops. Development 126, 5533-5546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronina V. A., Kozhemyakina E. A., O'Kernick C. M., Kahn N. D., Wenger S. L., Linberg J. V., Schneider A. S. and Mathers P. H. (2004). Mutations in the human RAX homeobox gene in a patient with anophthalmia and sclerocornea. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 315-322. 10.1093/hmg/ddh025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Lee J. E. and Dorsky R. I. (2009). Identification of Wnt-responsive cells in the zebrafish hypothalamus. Zebrafish 6, 49-58. 10.1089/zeb.2008.0570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Kopinke D., Lin J., McPherson A. D., Duncan R. N., Otsuna H., Moro E., Hoshijima K., Grunwald D. J., Argenton F. et al. (2012). Wnt signaling regulates postembryonic hypothalamic progenitor differentiation. Dev. Cell 23, 624-636. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullimann M. F., Puelles L. and Wicht H. (1999). Early postembryonic neural development in the zebrafish: a 3-D reconstruction of forebrain proliferation zones shows their relation to prosomeres. Eur. J. Morphol. 37, 117-121. 10.1076/ejom.37.2-3.0117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee C. L., Wang Y., Anderson S., Ekker M. and Rubenstein J. L. R. (2009). Arcuate nucleus expression of NKX2.1 and DLX and lineages expressing these transcription factors in neuropeptide Y(+), proopiomelanocortin(+), and tyrosine hydroxylase(+) neurons in neonatal and adult mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 517, 37-50. 10.1002/cne.22132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J., Morrissey M. E., Shine L., Kennedy C., Higgins D. G. and Kennedy B. N. (2014). Genes and signaling networks regulated during zebrafish optic vesicle morphogenesis. BMC Genomics 15, 825 10.1186/1471-2164-15-825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Mathers P. H. and Jamrich M. (2000). Function of Rx, but not Pax6, is essential for the formation of retinal progenitor cells in mice. Genesis 28, 135-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Zevallos S. E., Rizzoti K., Jeong Y., Lovell-Badge R. and Epstein D. J. (2012). Disruption of SoxB1-dependent Sonic hedgehog expression in the hypothalamus causes septo-optic dysplasia. Dev. Cell. 22, 585-596. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]