Abstract

Humor is sometimes employed in health messages. However, little is known about contingencies under which different types of humor may or may not be effective. This experiment crossed humorous vs. non-humorous and self- vs. other-deprecating messages about binge drinking, and tested how differences in personal investment in alcohol use moderates the effects of such messages on college binge drinkers. Results showed significant three-way interaction effects on subjective norms and behavioral intentions largely consistent with hypotheses. Assessment of significant differences in the interactions indicated that for binge drinkers who weren’t high in personal investment in alcohol use, other-deprecating humor tended to reduce their perceived subjective norms about the acceptability of binge drinking behavior and their behavioral intentions. The effect of the experimental manipulation on subjective norms among these binge drinkers was shown to mediate the effect on intentions to binge drink in the future. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Humor is a strategy sometimes employed in health messages. For example, the “That Guy” campaigns sponsored by U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) ridiculed binge drinkers who made fools of themselves when intoxicated (U.S. DoD, 2008). Humor as a communication strategy is likely to become of greater interest as the internet and social media become increasingly important channels for communicating health messages, given that humor appears to be one of the principal elements of internet messages that are widely spread via social media (see Miller, 2013; Vogelbacker, Dillehunt, & MacCallum, 2014). An emphasis on humor is reflected in Internet health information as well: A content analysis of anti-smoking video clips on YouTube found that among 87 video clips, 21.8% contained some kind of humor (Paek, Hove, & Jeon, 2013); a recent qualitative study underscored the utility of humor in communicating about sensitive health issues with youth (Evers, Albury, Byron, & Crawford, 2013).

Nonetheless, humor’s effects on attitudes and intentions to perform the behaviors depicted in health campaigns have not been systematically investigated (Lee, 2010). As a result, health communicators have little theoretical or empirical guidance regarding how humor may be received by different audiences.

Humor is not unidimensional. Although there are several different types of humor, including self-deprecating humor, other-deprecating humor, satire, irony, etc., previous research in health communication tends to consider only whether content is humorous or not (e.g., Lee & Ferguson, 2002; Lee, 2010). Although Alabastro, Beleva, and Crano (2012) examined the effects of two different types of sarcastic anti-drug messages (serious sarcastic vs. funny sarcastic humor) versus a non-humorous message, they focused on types of sarcasm, not on types of humor. The effects of different types of humor on individuals’ perception of health messages—and how these effects may vary as a function of audience differences–remain unexplored. This study, thus, will begin to address the complexity of humor. Specifically, this study will investigate the impact of self-deprecating versus other-deprecating humor on health message processing, largely from the perspective of Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

In addition to types of humor, people may respond to the same humorous health message differently based on individual differences, including self-monitoring (Lammers, 1991), sensation seeking (Galloway, 2009), and need for humor (Kellaris & Cline, 2007). Accordingly, we will propose hypotheses about the interaction effects of different types of humor and individual differences on attitudes, perceived subjective norms, and behavioral intentions (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) toward binge drinking among college students.

Binge Drinking

Binge drinking refers to consuming five/four or more standard drinks for men/women in about two hours (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 2004). Engaging in binge drinking is especially common among college students, and is implicated in tens of thousands of deaths, injuries, and sexual assaults each year (CDC, 2012). This study, therefore, will investigate the effect of humor on college binge drinkers’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral intentions towards binge drinking.

Humor in Health Communication

Humor can increase attention to a message (e.g. Monahan, 1994; Weinberger & Gulas, 1992) and source liking (Nabi, Moyer-Gusé, & Byrne, 2007). In addition, there is reason to believe that humorous messages may reduce biased processing (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986) or reactance (Brehm, 1966; Brehm & Brehm, 1981). For example, consider responses to a binge drinking message among targets of such messaging. Messages advocating reduction of drinking implicitly criticize individuals’ risky health behaviors (e.g., binge drinking). If persons are invested in their risky behavior, they are likely to respond to such messages with reactance or biased processing. Humor has the potential to reduce reactance and biased processing by de-emphasizing or rendering more indirect the negative judgment about the behavior (Yoon & Tinkham, 2013). For instance, Paek, Kim, and Hove (2010) found that humorous anti-smoking video clips on YouTube tended to be positively associated with numbers of viewers and viewer ratings.

It is, however, also possible that humor can have a boomerang effect on health-related outcomes. For instance, Moyer-Gusé, Mahood, and Brookes (2011) found that for male participants, humor is likely to reduce perceived severity of unprotected sex behaviors, which in turn, would increase their behavioral intentions of unprotected sex behaviors. Similarly, Alabastro et al. (2012) found that funny sarcastic anti-drug messages tend to be less persuasive than non-humorous and serious sarcastic messages. These mixed findings regarding humor effects in health communication suggest a need for a better understanding of factors that may influence the effectiveness of humor in health messages.

Self-deprecating vs. Other-deprecating Humor

Humor has a number of different types, including self-deprecating, other-deprecating, satire, parody, irony, comic wit and so forth (see Speck, 1991; Stewart, 2011). Among the different types of humor, two of the most common types of humor are self-deprecating and other-deprecating humor (Apte, 1985; Greengroos & Miller, 2008). As evidenced by previous humorous health campaign examples, those two types of humor are also relevant to health communication concerns. Self-deprecating humor refers to “comments used in an affiliative manner which invite the audience to share in the laughter at their [shared] self-targeted foibles” (Stewart, 2011, p. 205), whereas other-deprecating humor differentiates a speaker from the target and from those members of the audience who share the relevant characteristics of the target, as the source makes fun of the target (Meyer, 2000). In this sense, for self-deprecating humor, the narrator of an anti-binge drinking humorous message will be a binge drinker, and the binge drinker makes fun of his/her previous binge drinking experiences. For other-deprecating humor, on the other hand, the narrator of the message will be a non-binge drinker who makes fun of binge drinkers.

Prior studies have found that self-deprecating humor is more likely to establish an equal relationship between the speaker and the public than other deprecating-humor (e.g., Meyer, 2000; Stewart, 2011). In addition, through lowering the speaker’s status, self-deprecating humor is likely to provide advice without directly criticizing a certain behavior (e.g., binge drinking here) (Binsted, 1995). Therefore, self-deprecating humor may serve as a courtship behavior that leads to audiences feeling a sense of affiliation with the speaker as an in-group member, and also leads to submissive intentions (Lundy, Tan, & Cunningham, 1998). In other words, it seems the advantage of self-deprecating humor is to reduce reactance to a message that may be perceived as threatening by the intended audience, which in turn, leads to increased intentions about a behavior advocated in the message.

On the other hand, it would seem, by the same logic, that other-deprecating humor creates a sense of affiliation among those who perceive themselves as not sharing the characteristics of the target of the humor. Such audience members, by being amused, are implicitly invited to join the source as part of an in-group making fun of the out-group member (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Therefore, the advantage of other-deprecating humor is that it can lead to audience members distancing themselves from the behavior of the person who is the focus of the humor. However, unlike self-deprecating humor, other-deprecating humor is based on disrespecting others, and it therefore may offend audiences (Greengross & Miller, 2008). From this perspective, one might conclude that self-deprecating humor is a more effective way to influence behavioral intentions than other-deprecating humor.

Self- and other-deprecating humor, however, also have disinhibiting and inhibiting effects, respectively (Janes & Olson, 2010). Specifically, Janes and Olson (2010) found that people tend to inhibit a related behavior if they observe another person being ridiculed (other-deprecating humor), whereas people tend to less concerned about being negatively evaluated if they observe an individual making fun of himself or herself (self-deprecating humor). In other words, unlike our previous assumption, Janes and Olson’s (2010) findings indicate that other-deprecating humor has a greater impact on behavioral intentions than self-deprecating humor. Thus, it is plausible to assume that both lines of reasoning agree that self- and other-deprecating humor will operate in distinct ways.

However, we have not yet addressed the likely nature of such effects. Galloway (2009) argues that one way to increase understanding of humor effects is to identify individual difference variables that moderate those effects. We agree, believing the nature of these effects will be complex, moderated in turn by audience differences.

As we pointed out earlier, from a Social Identity Theory perspective, self-deprecating humor is likely to be more effective when the message challenges the behavior of the message recipient. In self-deprecating humor, the message is being delivered by an in-group member and the target is the narrator him or herself; the message recipient is implicated only indirectly and the narrator shares in the implicit criticism. There is no presumption of personal or moral superiority. In the context of binge drinking, if a narrator of a message (as a binge drinker) disparages his/her own previous binge drinking behaviors, it can be considered as self-deprecating humor. Conversely, it can be considered as other-deprecating humor if the narrator (as a non-binge drinker) makes fun of others’ binge drinking behaviors. Since the primary audience for anti-binge drinking campaign messages is binge drinkers, it might seem likely at first glance that they should prefer self- to other-deprecating messages.

Differences in Personal Investment in Binge Drinking

However, prior research complicates this picture. Previous findings indicate that college binge drinkers vary in their personal commitment to and investment in alcohol use apart from amount of consumption, perhaps because many drink largely due to campus drinking norms and not because of inherent love of heavy alcohol consumption (Slater, 2001). Moreover, differences in responses to different types of messages about binge drinking (narrative vs. statistical) were a function of these value-based differences, and not the amount of binge drinking per se (Slater & Rouner, 1996). Such differences have been conceptualized in terms of value-involvement and value-relevant processing in the Extended-ELM, and defensive processing in the Heuristic-Systematic Model (Chaiken, Liberman, & Eagly, 1989; Slater, 2002; Todorov, Chaiken, & Henderson, 2002). Value-involvement leads to biased processing (or value-relevant/defensive processing) to protect consistency with those values, much as issue-relevant involvement can lead to biased processing in the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM, Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The main difference between value-relevant processing and issue-relevant processing as addressed in the ELM (or outcome-relevant processing, to use the Heuristic-Systematic Model vocabulary), is that the latter arises when messages have direct potential impact on the audience (e.g., a message advocating an increase in drinking age or tougher enforcement of drinking-related laws), giving rise to attention to central message arguments. Value-relevant processing concerns messages that are identity-relevant but which do not directly pose threats to the recipient’s time, money, and choice, and thus do not necessarily evoke such central processing. What we here call personal investment in alcohol use is an instantiation of what is referred to as value-involvement in the Extended ELM, and is expected to result in value-relevant or defensive processing.

It appears that many college-age binge drinkers may not necessarily identify themselves with binge drinking behavior. Some (about 20%) of the total studied who were highly invested or value-involved in alcohol use expressed intentions to continue drinking in a similar way after college (Slater, 2001); for others, the drinking appeared to be situational and normatively driven.

Social Identity Theory posits that self-concept is comprised of the social identity related to the group to which a person belongs and personal identity (Reicher, Spears, & Postmes, 1995; Reicher, S., Spears, R., & Haslam, 2010). Specifically, social identity refers to “the individual’s knowledge that he belongs to certain social groups together with some emotional and value significance to him of this group membership” (Tajfel, 1972, p. 292). Further, based on social identity, individuals are likely to behave as members of a given group based on whatever the in-group norms happen to be.

From a Social Identity Theory perspective, then, it is drinkers who are personally invested in the behavior who will be most likely to consider a misbehaving binge drinker to be part of their in-group, and who will engage in defensive, value-relevant processing if the message seems to attack their in-group, as would be the case for other-deprecating humor. Those college drinkers for whom the behavior is situational are less likely to incorporate such a drinker into their in-group identity, and should be more likely to consider the drinker an out-group member, so other-deprecating humor should be acceptable and indeed, per Janes & Olson (2010), lead to distancing from such people and such behavior (especially if this source is also an in-group member, as will be the case here). If this logic proves correct,

-

H1

The effects of humorous messages containing either self-deprecating or other-deprecating humor on behavioral intentions among college binge drinkers will vary as a function of how much they value alcohol use; other-deprecating humor will tend to be relatively more effective for binge drinkers who value alcohol use less; the converse will be true for self-deprecating humor.

Subjective norms and attitudes as possible proximal outcomes

Our Social Identity Theory argument has an implicitly normative component. We suggest that other-deprecating humor frames the misbehaving binge drinker as an out-group member by making fun of the drinker and in so doing distances the message recipient from the binge drinker. If so, such humor should impact how message recipients believe their peers will judge such behavior—subjective norms, in the terminology of the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). On the other hand, message recipients might perceive engaging in binge drinking to be more acceptable by their peers when they read a self-deprecating humorous message in which a person—a peer—makes a joke of the consequences of their own binge drinking behavior.

Of course, given our earlier arguments, it may be that such an effect is further moderated by personal investment in alcohol use. If those less committed to alcohol use are likely to engage in binge drinking because other people do so rather than because of their own personal commitment to alcohol, they might be more likely to infer peer disapproval from an other-deprecating message than those more committed to their pattern of abusive use of alcohol. On the other hand, those highly committed to alcohol use might be less likely to be influenced by subjective norms of those who don’t share their relationship to alcohol use. Therefore, we ask:

-

RQ1

Is the effect of humor on subjective norms among binge drinkers contingent on both direction of deprecation and extent of personal investment in alcohol use?

For attitudes – the other predictor of behavioral intentions in the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) – the theoretical logic for the differential impact of other- vs. self-deprecation is less immediately apparent given our Social Identity Theory perspective. However, plausible arguments can be constructed. Other-deprecation may reduce the impact of a message on attitudes especially among those more committed to alcohol use. This might be especially true for humorous messages, in which other-deprecating messages might be seen as mocking the in-group:

-

H2

The effects of humorous messages containing either self- or other-deprecating humor on attitudes about binge drinking will vary as a function of how much the recipient values alcohol use.

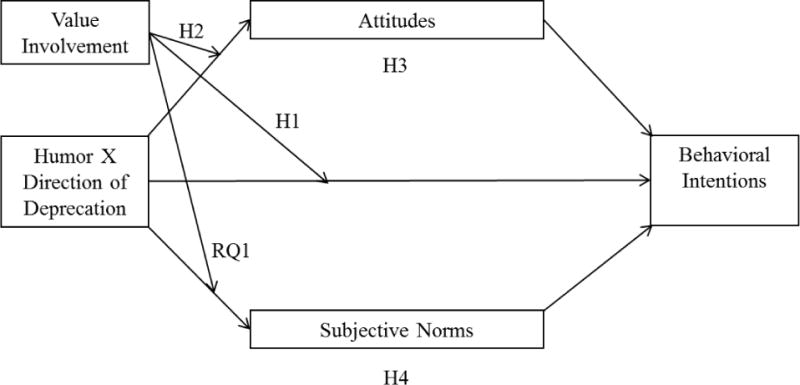

Given that behavioral intention is a function of subjective norms or attitudes or both from the perspective of the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1975; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), we can expect that binge drinkers low in personal investment in alcohol use might be highly influenced by subjective norms about binge drinking, which, in turn, influence their behavioral intentions in regard to engaging in this behavior. On the other hand, it is expected that binge drinkers high in personal investment in alcohol use might be influenced by their own attitudes about alcohol rather than by subjective norms. Their favorable attitudes toward alcohol might further influence their behavioral intentions in regard to engaging in binge-drinking behavior (see Figure 1). If this logic proves correct,

-

H3

Subjective norms will mediate the relationship between humor × direction of deprecation × personal investment in alcohol use and behavioral intentions.

-

H4

Attitudes will mediate the relationship between humor × direction of deprecation × personal investment in alcohol use and behavioral intentions.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of the three-way interaction effects between humor, direction of deprecation, and personal investment in alcohol use (a form of value involvement) on behavioral intention.

Assessing humor effects on secondary audiences

Although anti-binge drinking campaigns target binge drinkers, it is difficult to target specific audiences separately in most communication environments. Thus, secondary audiences (e.g., abstainers and moderate drinkers) are likely to be exposed to the campaign. It is, therefore, important to identify possible boomerang (or positive) effects on these non-binge drinkers. Therefore, we can ask:

-

RQ2

What is the effect of these humorous versus non-humorous messages on abstainers and moderate drinkers?

Method

Design Overview

A 2 [humor: humor vs. non-humor] × 2 [direction of deprecation: self vs. other] between subject factorial design tested the impacts of humor, message types, and personal investment in alcohol use (assessed as a continuous covariate and moderator) on behavioral intentions, subjective norms, and attitudes toward engaging in binge drinking for college binge drinkers and for secondary audiences.

Participants

In total, 309 undergraduate students aged from 18 to 32 (M = 20.34, SD = 1.81) at a large Midwestern university participated in this study in exchange for extra course credit. Because 199 participants (62.8% female) completed all sessions of this study, data from these participants were used for analysis.

Stimulus

Four different versions of the same message were created by a former professional screenwriter: humorous self-deprecating, humorous other-deprecating, non-humorous self-deprecating, and non-humorous other-deprecating messages based on pre-test. For the self-directed conditions, the narrator of the message tells a story about his previous binge drinking experiences, whereas for the other-directed conditions, the narrator introduces the same story as his friend’s experiences. Similarly, in humor conditions, the message conveys humor, whereas in non-humor conditions, the jokes and humorous tones were eliminated in favor of a serious tone. Except for these differences, the health message was kept as identical as possible across conditions: the essential narrative elements, the negative consequences, and the relevant statistical information were the same in each condition. Using a narrator who was a college student in all four conditions was important not only to keep experimental conditions parallel; since we are interested in ways that other-deprecating humor might distance message recipients from the target of the humor, it was important that the source be an in-group member. The humorous versions were just over 1,000 words and the non-humorous versions averaged about 900 words given the dropped jokes; we decided not to pad the non-humorous versions with extra verbiage because we were concerned they would be less effective as a result, slanting findings in the direction of the humorous versions. We didn’t want to add extra substance, of course, as then the actual content would differ between versions. The narrator used was male, based on prior research indicating that females identify with a male protagonist more readily than males identify with a female (Eyal & Rubin, 2003; Feilitzen & Linne, 1975).

Procedure

In session 1, all participants were asked to read a consent form and indicate their personal investment in alcohol use, average drinking amounts, and demographics online. Two days later, participants received an email to sign up for session 2. In session 2, participants were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions and asked to read a health message about binge drinking. Finally, they were asked to complete questionnaires, which contained items measuring personal investment in alcohol use, behavioral intentions, subjective norms, and attitudes toward the health behavior.

Measurement

Type of Drinker

Type of drinker was assessed during session 1 by asking participants how many drinks they normally have on drinking occasions. Based on the definition from NIAAA (2004), if male participants/female participants answered 5 or more/4 or more, they were coded as “binge drinkers” (3). Participants were coded as “abstainers” (1) if they answered 0 for this question. The rest of participants were coded as “moderate drinkers” (2). Results show that 89 participants were found to be binge drinkers, whereas 110 participants (i.e., 70 moderate drinkers and 40 abstainers) were non-binge drinkers (M = 2.25 SD = .77). As binge drinkers were the intended audience for the messages, they (N = 89) were the sole focus of all subsequent analyses except for RQ2 regarding the effects of humor on secondary audiences.

Personal investment in alcohol use

Personal investment in alcohol use, which we conceptualize as a form of value involvement (Johnson & Eagly, 1989; Slater, 2002), was measured by 7-point Likert-type response scales ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree” (Slater & Rouner, 1996, M = 3.26, SD = 1.26). Items include: 1) “If I were unable to drink anymore, I would feel a personal loss,” 2) “Alcohol – beer, wine, or liquor – plays an important role in my enjoyment of life,” 3) “A social occasion without alcohol is as enjoyable to me as one with alcohol (reverse-coded),” 4) “I really look forward to a drink or two in the evening or on weekends,” 5) “Something beneficial is missing from social occasions when alcohol is not served,” 6) “Drinking alcohol is simply part of a normal social life,” and 7) “In general, I value the contribution of alcoholic beverages to the quality of my life” (Cronbach’s α = .81, M = 3.91, SD = 1.05 for binge drinkers). Personal investment in alcohol use for binge drinkers was normally distributed (Skewness = .26, Kurtosis = −.37). Hayes (2005) argues that the practice of a median split or mean split is not recommended without a strong rationale for using it, since the practice disregards the differences within groups based on an arbitrary cutoff, and since it leads to information loss. Personal investment in alcohol use, therefore, was treated as a continuous covariate and moderating effects were assessed using interactions with the continuous covariate. We note that this variable was not significantly correlated with amount of alcohol consumption among participants in this study, who were as noted above all binge drinkers.

Behavioral Intentions

Behavioral intentions were measured by three 7-point scale items modified from Werder (2008): 1) “I intend to engage in binge drinking during the next month” on a scale anchored by unlikely/likely; 2) “I plan to drink a lot during the next month” on a scale anchored by never/frequently; 3) “I am likely to limit my drinking during the next month” on a scale anchored by strongly agree/strongly disagree (Cronbach’s α = .83, M = 3.55, SD = 1.84). We provided the NIH standard definition of binge drinking to participants so they had a shared understanding of the term when they responded.

Subjective norms

Three items using 7-point response scale ranging from I should not (1) to I should (7) were used to assess subjective norms: 1) “My close friends think__ engage in drinking four or more drinks in an evening,” 2) “My close friends think __enjoy binge drinking,” and 3) “My close friends think __drink four or more drinks at least once a week” (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980, Cronbach’s α = .87, M = 3.97, SD = 1.78).

Attitudes toward Health Behavior

Attitudes toward binge drinking were measured using an eleven-point semantic differential scale with four pairs of adjectives (harmful/beneficial, good/bad, rewarding/punishment, and unpleasant/pleasant) (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980, Cronbach’s α = .82, M = 3.40, SD = 1.84).

Control Variables

Unlike personal investment in alcohol use, outcome-relevant involvement is related to the achievement of a particular goal (Johnson & Eagly, 1989). For instance, for those high in outcome-relevant involvement with an issue, the issue is crucial to obtain their personal goals (Johnson & Eagly, 1989). In other words, participants in this study who are high in outcome relevant involvement can be those who have a specific goal to change their drinking behavior, and it is therefore plausible to assume that an anti-binge drinking message is highly relevant to that outcome. Therefore, outcome-relevant involvement was controlled by asking participants how important it was for them to change their drinking habits, with response options ranging from 1 (Not at all important) to 7 (Very important) (Braverman, 2008; M = 2.70, SD = 1.68). Previous exposure to the message was also controlled by asking participants whether they have seen the health message before with three options, yes, maybe, or no to control for the possibility of their having seen similar messages that might have influenced their responses.

Results

As a manipulation check, perceived humor was measured by four 7-point items (not funny/funny, not amusing/amusing, not entertaining/entertaining, not humorous/humorous) adopted from Nabi et al. (2007). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed to examine perceived humor as a function of humor, controlling for issue involvement and previous exposure. The analysis revealed that perceived humor was rated higher in the humor conditions (M = 4.16, SD = 1.68) than the non-humor conditions (M = 2.68, SD = 1.36), F(1, 191) =47.73, p < .0001. The analysis, however, did not reveal a significant main effect of self-deprecating (M = 3.53, SD = 1.70) vs. other-deprecating messages (M = 3.30, SD = 1.70) on perceived humor, F(1, 191) = .50, p > .05, or an interaction effect between humor and direction of deprecation, F(1, 191) = 1.31, p > .05 (see Table 1). The manipulation for humor, thus, was successful in that regardless of the direction of humor, participants perceived humorous messages to be more humorous than non-humorous messages, and effects of the two types of humor could not be explained because one was simply better executed than the other.

Table 1.

Interaction Effect between Humor and Direction of Deprecation on Perceived Humor

| Humor | Direction of deprecation | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-humor | Self-deprecating | 2.91a | 1.42 |

| Other-deprecating | 2.47a | 1.28 | |

| Humor | Self-deprecating | 4.11a | 1.74 |

| Other-deprecating | 4.22a | 1.64 |

F(1, 213) = 1.63, p > .05.

Note: Means with no subscript in common differ at p < .05.

Given that the narrator of the stimuli used was male, we tested perceived humor as a function of humor, direction of deprecation, and gender on perceived humor as well. An ANCOVA revealed no significant three-way interaction effect between humor × direction of deprecation × gender, F(1, 81) = 1.81, p > .05, two-way interaction effect between humor × gender, F(1, 81) = .00, p > .05, between direction of deprecation × gender, F(1, 81) = .18, p > .05, or main effect for gender, F(1, 81) = .04, p > .05, on perceived humor. Therefore, the humorous manipulation appeared to be equally effective for participants of each gender.

Hypotheses and Research Questions

Hypothesis H1

Hypothesis 1 suggested that personal investment in alcohol use will moderate the effects of humor vs. non-humor and self- vs. other-deprecation on intentions towards engaging in binge drinking. To examine the three-way interaction effect between humor, personal investment with alcohol, and direction of deprecation on behavioral intentions, controlling for issue involvement and previous exposure, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was first employed. Next, in order to investigate whether the interaction effect of humor and direction of deprecation on intentions to engage in binge drinking at a specific value of personal investment in alcohol use was statistically different from zero (i.e., a conditional effect of humor and direction of deprecation at values of personal investment in alcohol use), we further ran the data using the Johnson-Neyman (1936) technique with Model 3 in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) for SPSS. Lastly, in order to further probe the interaction, we split the data into two humor and non-humor conditions, and ran the data again using Johnson-Neyman technique with Model 1 in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013).

First, an ANCOVA revealed a significant three-way interaction effect between humor, personal investment in alcohol use, and direction of deprecation, F(1, 79) = 5.14, p <.05, partial η2 = .06, on behavioral intentions. As shown in Figure 2, for binge drinkers low in personal investment in alcohol use in non-humorous conditions, the self-deprecating message appeared to reduce their behavioral intentions toward engaging in binge drinking. For those high in personal investment in alcohol use, the same message appeared to increase their behavioral intentions. For other-deprecating non-humorous messages, behavioral intentions did not appear to vary much for personal investment in alcohol use.

Figure 2.

Three-way interaction effect between self- vs. other-deprecation, humor vs. non-humor, and personal investment in alcohol use (a form of value involvement) on behavioral intention toward engaging in binge drinking

When the message was humorous, however, for binge drinkers low in personal investment in alcohol use, the other-deprecating message tended to reduce their behavioral intentions toward engaging in binge drinking. For those high in personal investment in alcohol use, the same message appeared to increase their behavioral intentions. For the self-deprecating message, whether personal investment in alcohol use was high or low did not make a notable difference for behavioral intentions.

Next, in order to investigate a conditional effect of humor and direction of deprecation at values of personal investment in alcohol use, the Johnson-Neyman (1936) technique in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) for SPSS was used. Model 3 in PROCESS was employed with 10,000 bootstrap resamples to test this conditional effect. Specifically, humor was entered as the predictor and direction of deprecation and personal investment in alcohol use were included as the moderators. Again, issue involvement and previous exposure were entered as the covariates. Results indicate that the interaction effect between humor and direction of deprecation is significantly related to intentions toward engaging in binge drinking only among binge drinkers with scores below 3.79 on personal investment in alcohol use (ӨX→Y|M=3.79 = −1.15, p < .05). Among binge drinkers with scores above 3.79 on personal investment in alcohol use, there is no statistically significant relation between humor and direction of deprecation on intention. The 95% bootstrapped confidence band when ӨX→Y|M > 3.79 does not exclude zero.

To further probe this interaction, we split the data into two, humor and non-humor conditions, and ran the data again using Johnson-Neyman technique in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013). Model 1 in PROCESS was employed with 10,000 bootstrap resamples to test the conditional effect of direction of deprecation on intentions at values of personal investment in alcohol use. Specifically, direction of deprecation was entered as the predictor, and personal investment in alcohol use was included as the mediator. Again, issue involvement and previous exposure were entered as the covariates. Results indicate that when messages were non-humorous, the level of personal investment in alcohol use did not interact with direction of deprecation to influence behavioral intention. However, results indicate that when messages are humorous, direction of deprecation is related to intention only among binge drinkers with scores below 3.96 on personal investment in alcohol use (ӨX→Y|M=3.96 = −.81, p < .05). Among binge drinkers with scores above 3.96 on personal investment in alcohol use, there is no statistically significant association between direction of deprecation and behavioral intention.

In summary, H1 was supported, such that for binge drinkers relatively low or moderate in personal investment in alcohol use, when the message is humorous the other-deprecating message tended to have a persuasive effect. On the other hand, for binge drinkers relatively high in personal investment in alcohol use, whether the message is humorous or not and whether the message is self-deprecating or other-deprecating did not make a statistically significant difference for behavioral intentions. While the appearance of the interaction suggested possible boomerang effects of other-deprecating humor on these committed binge drinkers, such boomerang effects did not achieve statistical significance when the interaction was probed.

Research Question 1

An ANCOVA was first employed to examine RQ1 about the three-way interaction effect between humor, direction of deprecation, and personal investment in alcohol use on subjective norms. We then further ran the data using the Johnson-Neyman (1936) technique with Model 3 in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to investigate a conditional effect of humor and direction of deprecation at values of personal investment in alcohol use.

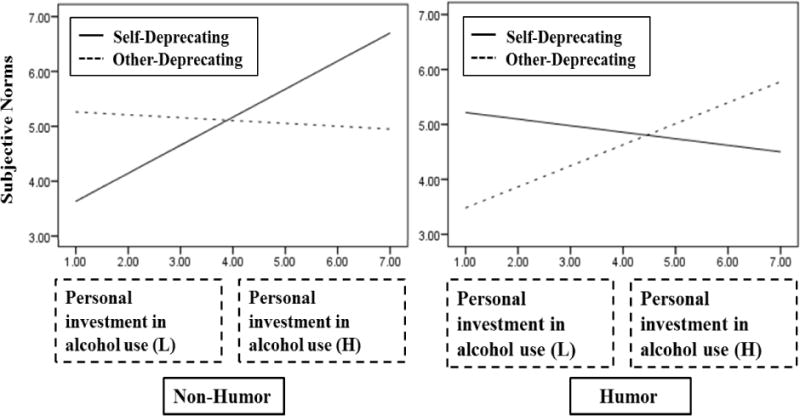

An ANCOVA revealed a significant three-way interaction effect between humor, personal investment in alcohol use, and direction of deprecation on subjective norms, F(1, 79) = 4.22, p < .05, partial η2 = .05, largely consistent with H1. As shown in Figure 3, when the message was non-humorous, for binge drinkers low in personal investment in alcohol use, the self-deprecating message appeared to decrease subjective norms supportive of binge drinking. For those high in personal investment in alcohol use, the same message appeared to increase such subjective norms. When the message was humorous, however, for binge drinkers low in personal investment in alcohol use the other-deprecating message tended to reduce subjective norms supportive of binge drinking. For binge drinkers high in personal investment in alcohol use, the same message appeared to increase such subjective norms.

Figure 3.

Three-way interaction effect between self- vs. other-deprecation, humor vs. non-humor, and personal investment in alcohol use on subjective norms

Again, to test a conditional effect of humor and direction of humor at values of personal investment in alcohol use on subjective norms, we used the Johnson-Neyman technique in the Process macro (Hayes, 2013). Specifically, Model 3 in PROCESS was employed with 10,000 bootstrap resamples. Humor was included as the predictor, and direction of deprecation and personal investment in alcohol use were included as the moderators. Issue involvement and previous exposure were entered as the covariates. Results indicate that the interaction effect between humor and direction of deprecation is related to subjective norms about binge drinking among binge drinkers with scores below 2.68 on personal investment in alcohol use (ӨX→Y|M=3.79 = −1.15, p < .05). Among binge drinkers with scores above 2.68 on personal investment in alcohol use, there is no statistically significant interaction effect between humor and direction of deprecation on subjective norms. In other words, as with H1, the significant effect is attributable to the effectiveness of the other-deprecating humor with binge drinkers who did not score high on personal investment in alcohol use; apparent boomerang effects of such humor with those highly invested did not reach statistical significance.

Hypothesis 2

An ANCOVA was employed to test H2 that personal investment in alcohol use will moderate the effects of humor vs. non-humor and self vs. other deprecation on attitude towards engaging in binge drinking. No significant three-way effect of humor, personal investment in alcohol use, and direction of deprecation on attitude was found, F(1, 79) = .03, p > .05, partial η2 = .00. Thus, H2 was not supported.

Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 4

Model 12 in PROCESS (Hayes, 2013) was employed with 10,000 bootstrap resamples to test hypotheses 3 and 4 that subjective norms and attitudes, respectively, will each mediate the three-way interaction effects of humor, direction of deprecation, and personal investment in alcohol use on behavioral intentions toward engaging in binge drinking. Specifically, in the model, we entered humor as the predictor, direction of deprecation and personal investment in alcohol use as the moderators, subjective norms and attitudes as the mediators, and issue involvement and previous exposure as the covariates. Analyses showed an indirect effect of humor × direction of deprecation × personal investment in alcohol use interaction on behavioral intentions towards engaging in binge drinking through subjective norms (95% bias-corrected confidence interval of [.04, 1.33]), but not through attitudes (95% bias-corrected confidence interval of [−.29, .15]). Therefore, support was found only for H3.

Research Question 2

An ANCOVA was employed to test Research Question 2 concerning potential for boomerang (or positive) effects of humorous messages on secondary audiences. No significant main effect of humor vs. non-humor was found for secondary audiences on behavioral intentions, subjective norms, or attitudes.

Discussion

These findings provide support for our contention that the effects of humor on health-related perceived norms and behavioral intentions is contingent both on the type of humor and on audience differences. In particular, our findings suggest, consistent with the Social Identity Theory perspective and prior research on self- vs. other-deprecating humor, that for message recipients not personally involved with and committed to the target behavior, other-deprecating humor can impact intentions through increasing perceptions that peers—members of their own reference group—do not approve of the behavior. This is not the case for those who are more strongly committed to the behavior, and indeed there is some suggestion (though not at statistically significant levels) that other-deprecating humor, though more effective overall, may have the potential to boomerang with such audiences.

This research was focused on college binge drinking, a particularly challenging topic for health communication and one with a variety of distinctive challenges. Our findings are consistent with prior research (Slater & Rouner, 1996; Slater, 2001) showing that college binge drinkers are not homogeneous with respect to their commitment to alcohol use, and that this difference is reflected in very different responses to messages.

Specifically, the results indicated that regardless of whether the message was humorous or not or whether the message deprecated self or other, binge drinkers high in personal investment in alcohol use (those high in defense motivation) tended to be less influenced in all conditions, and in particular responded very differently than other binge drinkers to humor that was other-deprecating relative to messages that used self-deprecating humor. Such findings underscore the importance of the distinction between more- and less-committed binge drinkers in examining effects of messages directed at college student drinkers.

Our findings regarding the importance of commitment to binge drinking are interesting theoretically, in that they provide additional support for the E-ELM argument regarding the importance of motivation and social identity in how messages are processed. The findings of this study also may help account for prior mixed findings of humor effects on individuals’ perception of health behaviors by highlighting several contingencies that should be considered when studying persuasive effects of humor (e.g., Alabastro et al., 2012; Moyer-Gusé et al., 2011).

Such findings are also of practical interest. Segmenting audiences for health communication by patterns of risk behavior is clearly sensible. These results suggest something less obvious: that even among those evincing a given level of risk behavior, the level of investment in the behavior may vary and this difference may dramatically influence responses to persuasive efforts. Whether this holds beyond the case of college binge drinking remains largely unstudied, but is worthy of research attention. Similarly, practitioners may well take note of the findings that suggest other-deprecating humor has the potential to be effective among those not closely identified with the behavior pattern, but, unsurprisingly, is likely not to be well-received by those more closely identified with the behavior. The surprise, perhaps, is that many of those one might have anticipated to be resistant to other-deprecating humor may be less so than expected; if there is some ambivalence about the behavior, the other-deprecating humor may lead people to perceive less social acceptance for the behavior and to distance themselves from the behavior that is being made fun of.

In addition, we confirmed that there were no boomerang effects—or indeed, effects of any kind of note—of the experimental manipulations on secondary audiences: abstainers and moderate drinkers. This is good news, at least with respect to the complexities inherent in using humor as a health communication strategy.

Limitations and future research

This study has a variety of limitations consequent of our choice of topic. First, we used only one risky health behavior, binge drinking, in which the message sought to discourage performing a behavior valued by many in the intended audience. It would be useful to see if results replicate for other risky behaviors in which personal investment (value involvement) may vary—for example, men who have unprotected sex with men, contrasting those for whom risky casual sex is an important part of their self-image versus those who identify less with such behavior, even if they do engage in it as well.

Humor, moreover, may have consistently positive effects in other types of health messages that promote a health behavior rather than encouraging cessation of a behavior. For example, humorous messages promoting exercise or sun screen use may not face the problem of attacking valued behaviors of audience members, so long as the messages are not belittling people for not exercising or failing to use sunscreen. Future studies might well examine self- versus other-deprecating humor in contexts in which there is less personal investment in doing or not doing the behavior than is the case with alcohol use among college students.

One reason why humor is seldom studied is, very likely, the difficulty of creating experimental manipulations that are both rigorous and amusing. Messages for this study were created by a former professional comedy writer to permit rigorous manipulation of self- vs. other-deprecation and humor vs. non-humor content holding narrative and statistical elements constant, while maintaining in the respective conditions a tone consistent with a humorous or non-humorous message. In so doing, we sought to balance the ecological validity of creating quality humorous and non-humorous messages that were, nonetheless, largely equivalent on aspects apart from the humor, and believe that this study is unusual in the quality and rigor of the humor manipulation as a result.

However, we cannot exclude the possibility not only that effects may vary for different topics, but that different approaches to the same base message might influence results. In particular, it should be noted that our other-disparaging condition used a former college student as the narrative source; if the source that is making fun of the behavior is not an in-group member, the chances that the message will induce reactance are likely to increase and there is less reason to think that the recipients will align themselves with the source and distance themselves from the person showing the undesirable behavior. In addition, we used a male protagonist, based, as mentioned earlier, on research indicating that females are more able to identify with a male protagonist than the reverse. It is certainly possible, however, that females responded less than males to these stories despite showing no difference on the humor manipulation check, reducing effect sizes overall. Incorporating sex as an additional moderator and testing four-way interactions seemed excessively complex for this study; future research might profit by more systematically crossing and testing sex of protagonist and of audience members.

It is our hope that this study will help spur more careful and nuanced consideration of the various types and approaches to humor in persuasive and health communication, and encourage recognition of how these effects may vary as a function of audience member differences. As health communicators increasingly contend with media environments in which humor is frequently employed, increased theoretical and empirical guidance—and hints regarding potential pitfalls—become more and more important.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was in part supported by grant AA10377 from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to the second author. The opinions and interpretations expressed herein are the authors’ own.

References

- Alabastro A, Beleva Y, Crano WD. Why sarcasm works: Comparing sarcastic versus direct anti-drug messages; Poster presentation at the annual meeting at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP); San Diego, CA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Apte ML. Humor and Laughter: An Anthropological Approach. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Binsted K. Using humour to make natural language interfaces more friendly; Proceedings of AI, ALife, and Entertainment Workshop, International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI); Montreal, Canada. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Braverman J. Testimonials versus informational persuasive messages: The moderating effect of delivery mode and personal involvement. Communication Research. 2008;35:666–694. doi: 10.1177/0093650208321785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm J. A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm SS, Brehm JW. Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. San Diego, CA: Academic; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken S, Liberman A, Eagly A. Heuristic and systematic processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In: Uleman JS, Bargh JA, editors. Unintended thought. New York, NY: Guilford; 1989. pp. 122–252. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Binge drinking: National problem, local solutions. CDC Vitalsigns. 2012 Jan; Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2012-01-vitalsigns.pdf.

- Evers CW, Albury K, Byron P, Crawford K. Young people, social media, social network sites and sexual health communication in Australia: “This is funny, you should watch it”. International Journal of Communication. 2013;7:18. [Google Scholar]

- Eyal K, Rubin AM. Viewer aggression and homophily, identification, and parasocial relationships with television characters. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2003;47:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Feilitzen CV, Linne O. Identifying with television characters. Journal of Communication. 1975;25:51–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1975.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway G. Humor and ad liking: Evidence that sensation seeking moderates the effects of incongruity-resolution humor. Psychology & Marketing. 2009;26:779–792. doi: 10.1002/mar.20299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greengross G, Miller GF. Dissing oneself versus dissing rivals: Effects of status. personality, and sex on the short-term and long-term attractiveness of self-deprecating and other-deprecating humor. Evolutionary Psychology. 2008;6:393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Statistical methods for communication science. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffner C. Children’s wishful identification and parasocial interaction with favorite television characters. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1996;40:389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Janes LM, Olson JM. Is it you or is it me? Contrasting effects of ridicule targeting other people versus the self. Europe’s Journal of Psychology. 2010;6:46–70. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v6i3.208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Eagly AH. Effects of involvement in persuasion: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106:290–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kellaris J, Cline T. Humor and ad memorability: On the contributions of humor expectancy, relevancy, and need for humor. Psychology & Marketing. 2007;24:497–509. doi: 10.1002/mar.20170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers HB. The moderating influence of self-monitoring and gender on responses to humorous advertising. Journal of Social Psychology. 1991;131:57–70. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1991.9713824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ. The effects of self-efficacy statements in humorous anti-alcohol abuse messages targeting college students: Who is in charge? Health Communication. 2010;25:638–646. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.521908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Ferguson MA. The effects of anti-tobacco advertisements based on risk-taking tendencies: Realistic fear ads versus gross humor ads. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2002;79:945–963. doi: 10.1177/107769900207900411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy DE, Tan J, Cunningham MR. Heterosexual romantic preferences: The importance of humor and physical attractiveness for different types of relationships. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:311–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00174.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JC. Humor as a double-edged sword: Four functions of humor in communication. Communication Theory. 2000;10:310–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2000.tb00194.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AS. The Zombie Apocalypse: The Viral Impact of Social Media Marketing on Health. Journal of Consumer Health On the Internet. 2013;17:362–368. doi: 10.1080/15398285.2013.833447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan JL. Thinking positively: Using positive affect when designing messages. In: Maibach E, Parrott R, editors. Designing health messages. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Gusé E, Mahood C, Brookes S. Entertainment-education in the context of humor: Effects on safer sex intentions and risk perceptions. Health Communication. 2011;26:1–10. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.566832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi RL, Moyer-Guse E, Byrne S. All joking aside: A serious investigation into the persuasive effect of funny social issue messages. Communication Monographs. 2007;74:29–54. doi: 10.1080/03637750701196896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004 Winter;3 Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_Number3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Paek HJ, Hove T, Jeon J. Social media for message testing: A multilevel approach to linking favorable viewer responses with message, producer, and viewer influence on YouTube. Health Communication. 2013;28:226–236. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.672912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek HJ, Kim K, Hove T. Content analysis of antismoking videos on YouTube: Message sensation value, message appeals, and their relationships with viewer responses. Health education research. 2010;25:1085–1099. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Communication and persuasion: central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reicher SD, Spears R, Postmes T. A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. European Review of Social Psychology. 1995;6:161–198. [Google Scholar]

- Reicher S, Spears R, Haslam A. The social identity approach in social psychology. In: Wetherell MS, Mohanty CT, editors. Sage Identities Handbook. London: Sage; 2010. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Involvement as goal-directed strategic processing: Extending the Elaboration Likelihood Model. In: Dillard JP, Pfau M, editors. The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Personal value of alcohol use as a predictor of intention to decrease post-college alcohol use. Journal of drug education. 2001;31:263–269. doi: 10.2190/V8Q4-7M7C-Y1Y0-AV59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Rouner DL. Value-affirmative and value-protective processing of alcohol education messages that include statistical or anecdotal evidence. Communication Research. 1996;23:210–235. doi: 10.1177/009365096023002003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speck PS. The humorous message taxonomy: A framework for the study of humorous ads. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising. 1991;13:1–44. doi: 10.1080/01633392.1991.10504957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PA. The influence of self- and other-deprecatory humor on presidential candidate evaluation during the 2008 US election. Social Science Information. 2011;50:201–222. doi: 10.1177/0539018410396616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Experiments in a vacuum. In: Israel J, Tajfel H, editors. The context of social psychology. London: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 69–119. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov A, Chaiken S, Henderson MD. The heuristic-systematic model of social information processing. In: Dillard JP, Pfau M, editors. The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) That Guy. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.thatguy.com.

- Vogelbacker K, Dillahunt X, McCollum D. The Path from New to Viral: Understanding What Makes Videos Go Viral. iConference 2014 Proceedings. 2014:1145–1148. doi: 10.9776/14406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger MG, Gulas CS. The impact of humor in advertising: A review. Journal of Advertising. 1992;21:35–59. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1992.10673384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werder KP. The effect of doing good: An experimental analysis of the influence of corporate social responsibility initiatives on beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intention. International Journal of Strategic Communication. 2008;2:115–135. doi: 10.1080/15531180801974904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HJ, Tinkham SF. Humorous threat persuasion in advertising: The effects of humor, threat intensity, and issue involvement. Journal of Advertising. 2013;42:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2012.749082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]